Archer Library

Quantitative research: literature review .

- Archer Library This link opens in a new window

- Research Resources handout This link opens in a new window

- Locating Books

- Library eBook Collections This link opens in a new window

- A to Z Database List This link opens in a new window

- Research & Statistics

- Literature Review Resources

- Citations & Reference

Exploring the literature review

Literature review model: 6 steps.

Adapted from The Literature Review , Machi & McEvoy (2009, p. 13).

Your Literature Review

Step 2: search, boolean search strategies, search limiters, ★ ebsco & google drive.

1. Select a Topic

"All research begins with curiosity" (Machi & McEvoy, 2009, p. 14)

Selection of a topic, and fully defined research interest and question, is supervised (and approved) by your professor. Tips for crafting your topic include:

- Be specific. Take time to define your interest.

- Topic Focus. Fully describe and sufficiently narrow the focus for research.

- Academic Discipline. Learn more about your area of research & refine the scope.

- Avoid Bias. Be aware of bias that you (as a researcher) may have.

- Document your research. Use Google Docs to track your research process.

- Research apps. Consider using Evernote or Zotero to track your research.

Consider Purpose

What will your topic and research address?

In The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students , Ridley presents that literature reviews serve several purposes (2008, p. 16-17). Included are the following points:

- Historical background for the research;

- Overview of current field provided by "contemporary debates, issues, and questions;"

- Theories and concepts related to your research;

- Introduce "relevant terminology" - or academic language - being used it the field;

- Connect to existing research - does your work "extend or challenge [this] or address a gap;"

- Provide "supporting evidence for a practical problem or issue" that your research addresses.

★ Schedule a research appointment

At this point in your literature review, take time to meet with a librarian. Why? Understanding the subject terminology used in databases can be challenging. Archer Librarians can help you structure a search, preparing you for step two. How? Contact a librarian directly or use the online form to schedule an appointment. Details are provided in the adjacent Schedule an Appointment box.

2. Search the Literature

Collect & Select Data: Preview, select, and organize

Archer Library is your go-to resource for this step in your literature review process. The literature search will include books and ebooks, scholarly and practitioner journals, theses and dissertations, and indexes. You may also choose to include web sites, blogs, open access resources, and newspapers. This library guide provides access to resources needed to complete a literature review.

Books & eBooks: Archer Library & OhioLINK

| Books | |

Databases: Scholarly & Practitioner Journals

Review the Library Databases tab on this library guide, it provides links to recommended databases for Education & Psychology, Business, and General & Social Sciences.

Expand your journal search; a complete listing of available AU Library and OhioLINK databases is available on the Databases A to Z list . Search the database by subject, type, name, or do use the search box for a general title search. The A to Z list also includes open access resources and select internet sites.

Databases: Theses & Dissertations

Review the Library Databases tab on this guide, it includes Theses & Dissertation resources. AU library also has AU student authored theses and dissertations available in print, search the library catalog for these titles.

Did you know? If you are looking for particular chapters within a dissertation that is not fully available online, it is possible to submit an ILL article request . Do this instead of requesting the entire dissertation.

Newspapers: Databases & Internet

Consider current literature in your academic field. AU Library's database collection includes The Chronicle of Higher Education and The Wall Street Journal . The Internet Resources tab in this guide provides links to newspapers and online journals such as Inside Higher Ed , COABE Journal , and Education Week .

The Chronicle of Higher Education has the nation’s largest newsroom dedicated to covering colleges and universities. Source of news, information, and jobs for college and university faculty members and administrators

The Chronicle features complete contents of the latest print issue; daily news and advice columns; current job listings; archive of previously published content; discussion forums; and career-building tools such as online CV management and salary databases. Dates covered: 1970-present.

Offers in-depth coverage of national and international business and finance as well as first-rate coverage of hard news--all from America's premier financial newspaper. Covers complete bibliographic information and also subjects, companies, people, products, and geographic areas.

Comprehensive coverage back to 1984 is available from the world's leading financial newspaper through the ProQuest database.

Newspaper Source provides cover-to-cover full text for hundreds of national (U.S.), international and regional newspapers. In addition, it offers television and radio news transcripts from major networks.

Provides complete television and radio news transcripts from CBS News, CNN, CNN International, FOX News, and more.

Search Strategies & Boolean Operators

There are three basic boolean operators: AND, OR, and NOT.

Used with your search terms, boolean operators will either expand or limit results. What purpose do they serve? They help to define the relationship between your search terms. For example, using the operator AND will combine the terms expanding the search. When searching some databases, and Google, the operator AND may be implied.

Overview of boolean terms

| Search results will contain of the terms. | Search results will contain of the search terms. | Search results the specified search term. |

| Search for ; you will find items that contain terms. | Search for ; you will find items that contain . | Search for online education: you will find items that contain . |

| connects terms, limits the search, and will reduce the number of results returned. | redefines connection of the terms, expands the search, and increases the number of results returned. | excludes results from the search term and reduces the number of results. |

|

Adult learning online education: |

Adult learning online education: |

Adult learning online education: |

About the example: Boolean searches were conducted on November 4, 2019; result numbers may vary at a later date. No additional database limiters were set to further narrow search returns.

Database Search Limiters

Database strategies for targeted search results.

Most databases include limiters, or additional parameters, you may use to strategically focus search results. EBSCO databases, such as Education Research Complete & Academic Search Complete provide options to:

- Limit results to full text;

- Limit results to scholarly journals, and reference available;

- Select results source type to journals, magazines, conference papers, reviews, and newspapers

- Publication date

Keep in mind that these tools are defined as limiters for a reason; adding them to a search will limit the number of results returned. This can be a double-edged sword. How?

- If limiting results to full-text only, you may miss an important piece of research that could change the direction of your research. Interlibrary loan is available to students, free of charge. Request articles that are not available in full-text; they will be sent to you via email.

- If narrowing publication date, you may eliminate significant historical - or recent - research conducted on your topic.

- Limiting resource type to a specific type of material may cause bias in the research results.

Use limiters with care. When starting a search, consider opting out of limiters until the initial literature screening is complete. The second or third time through your research may be the ideal time to focus on specific time periods or material (scholarly vs newspaper).

★ Truncating Search Terms

Expanding your search term at the root.

Truncating is often referred to as 'wildcard' searching. Databases may have their own specific wildcard elements however, the most commonly used are the asterisk (*) or question mark (?). When used within your search. they will expand returned results.

Asterisk (*) Wildcard

Using the asterisk wildcard will return varied spellings of the truncated word. In the following example, the search term education was truncated after the letter "t."

| Original Search | |

| adult education | adult educat* |

| Results included: educate, education, educator, educators'/educators, educating, & educational |

Explore these database help pages for additional information on crafting search terms.

- EBSCO Connect: Basic Searching with EBSCO

- EBSCO Connect: Searching with Boolean Operators

- EBSCO Connect: Searching with Wildcards and Truncation Symbols

- ProQuest Help: Search Tips

- ERIC: How does ERIC search work?

★ EBSCO Databases & Google Drive

Tips for saving research directly to Google drive.

Researching in an EBSCO database?

It is possible to save articles (PDF and HTML) and abstracts in EBSCOhost databases directly to Google drive. Select the Google Drive icon, authenticate using a Google account, and an EBSCO folder will be created in your account. This is a great option for managing your research. If documenting your research in a Google Doc, consider linking the information to actual articles saved in drive.

EBSCO Databases & Google Drive

EBSCOHost Databases & Google Drive: Managing your Research

This video features an overview of how to use Google Drive with EBSCO databases to help manage your research. It presents information for connecting an active Google account to EBSCO and steps needed to provide permission for EBSCO to manage a folder in Drive.

About the Video: Closed captioning is available, select CC from the video menu. If you need to review a specific area on the video, view on YouTube and expand the video description for access to topic time stamps. A video transcript is provided below.

- EBSCOhost Databases & Google Scholar

Defining Literature Review

What is a literature review.

A definition from the Online Dictionary for Library and Information Sciences .

A literature review is "a comprehensive survey of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works" (Reitz, 2014).

A systemic review is "a literature review focused on a specific research question, which uses explicit methods to minimize bias in the identification, appraisal, selection, and synthesis of all the high-quality evidence pertinent to the question" (Reitz, 2014).

Recommended Reading

About this page

EBSCO Connect [Discovery and Search]. (2022). Searching with boolean operators. Retrieved May, 3, 2022 from https://connect.ebsco.com/s/?language=en_US

EBSCO Connect [Discover and Search]. (2022). Searching with wildcards and truncation symbols. Retrieved May 3, 2022; https://connect.ebsco.com/s/?language=en_US

Machi, L.A. & McEvoy, B.T. (2009). The literature review . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press:

Reitz, J.M. (2014). Online dictionary for library and information science. ABC-CLIO, Libraries Unlimited . Retrieved from https://www.abc-clio.com/ODLIS/odlis_A.aspx

Ridley, D. (2008). The literature review: A step-by-step guide for students . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Archer Librarians

Schedule an appointment.

Contact a librarian directly (email), or submit a request form. If you have worked with someone before, you can request them on the form.

- ★ Archer Library Help • Online Reqest Form

- Carrie Halquist • Reference & Instruction

- Jessica Byers • Reference & Curation

- Don Reams • Corrections Education & Reference

- Diane Schrecker • Education & Head of the IRC

- Tanaya Silcox • Technical Services & Business

- Sarah Thomas • Acquisitions & ATS Librarian

- << Previous: Research & Statistics

- Next: Literature Review Resources >>

- Last Updated: Aug 29, 2024 11:19 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ashland.edu/quantitative

Archer Library • Ashland University © Copyright 2023. An Equal Opportunity/Equal Access Institution.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved September 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

Literature Review

What exactly is a literature review.

- Critical Exploration and Synthesis: It involves a thorough and critical examination of existing research, going beyond simple summaries to synthesize information.

- Reorganizing Key Information: Involves structuring and categorizing the main ideas and findings from various sources.

- Offering Fresh Interpretations: Provides new perspectives or insights into the research topic.

- Merging New and Established Insights: Integrates both recent findings and well-established knowledge in the field.

- Analyzing Intellectual Trajectories: Examines the evolution and debates within a specific field over time.

- Contextualizing Current Research: Places recent research within the broader academic landscape, showing its relevance and relation to existing knowledge.

- Detailed Overview of Sources: Gives a comprehensive summary of relevant books, articles, and other scholarly materials.

- Highlighting Significance: Emphasizes the importance of various research works to the specific topic of study.

How do Literature Reviews Differ from Academic Research Papers?

- Focus on Existing Arguments: Literature reviews summarize and synthesize existing research, unlike research papers that present new arguments.

- Secondary vs. Primary Research: Literature reviews are based on secondary sources, while research papers often include primary research.

- Foundational Element vs. Main Content: In research papers, literature reviews are usually a part of the background, not the main focus.

- Lack of Original Contributions: Literature reviews do not introduce new theories or findings, which is a key component of research papers.

Purpose of Literature Reviews

- Drawing from Diverse Fields: Literature reviews incorporate findings from various fields like health, education, psychology, business, and more.

- Prioritizing High-Quality Studies: They emphasize original, high-quality research for accuracy and objectivity.

- Serving as Comprehensive Guides: Offer quick, in-depth insights for understanding a subject thoroughly.

- Foundational Steps in Research: Act as a crucial first step in conducting new research by summarizing existing knowledge.

- Providing Current Knowledge for Professionals: Keep professionals updated with the latest findings in their fields.

- Demonstrating Academic Expertise: In academia, they showcase the writer’s deep understanding and contribute to the background of research papers.

- Essential for Scholarly Research: A deep understanding of literature is vital for conducting and contextualizing scholarly research.

A Literature Review is Not About:

- Merely Summarizing Sources: It’s not just a compilation of summaries of various research works.

- Ignoring Contradictions: It does not overlook conflicting evidence or viewpoints in the literature.

- Being Unstructured: It’s not a random collection of information without a clear organizing principle.

- Avoiding Critical Analysis: It doesn’t merely present information without critically evaluating its relevance and credibility.

- Focusing Solely on Older Research: It’s not limited to outdated or historical literature, ignoring recent developments.

- Isolating Research: It doesn’t treat each source in isolation but integrates them into a cohesive narrative.

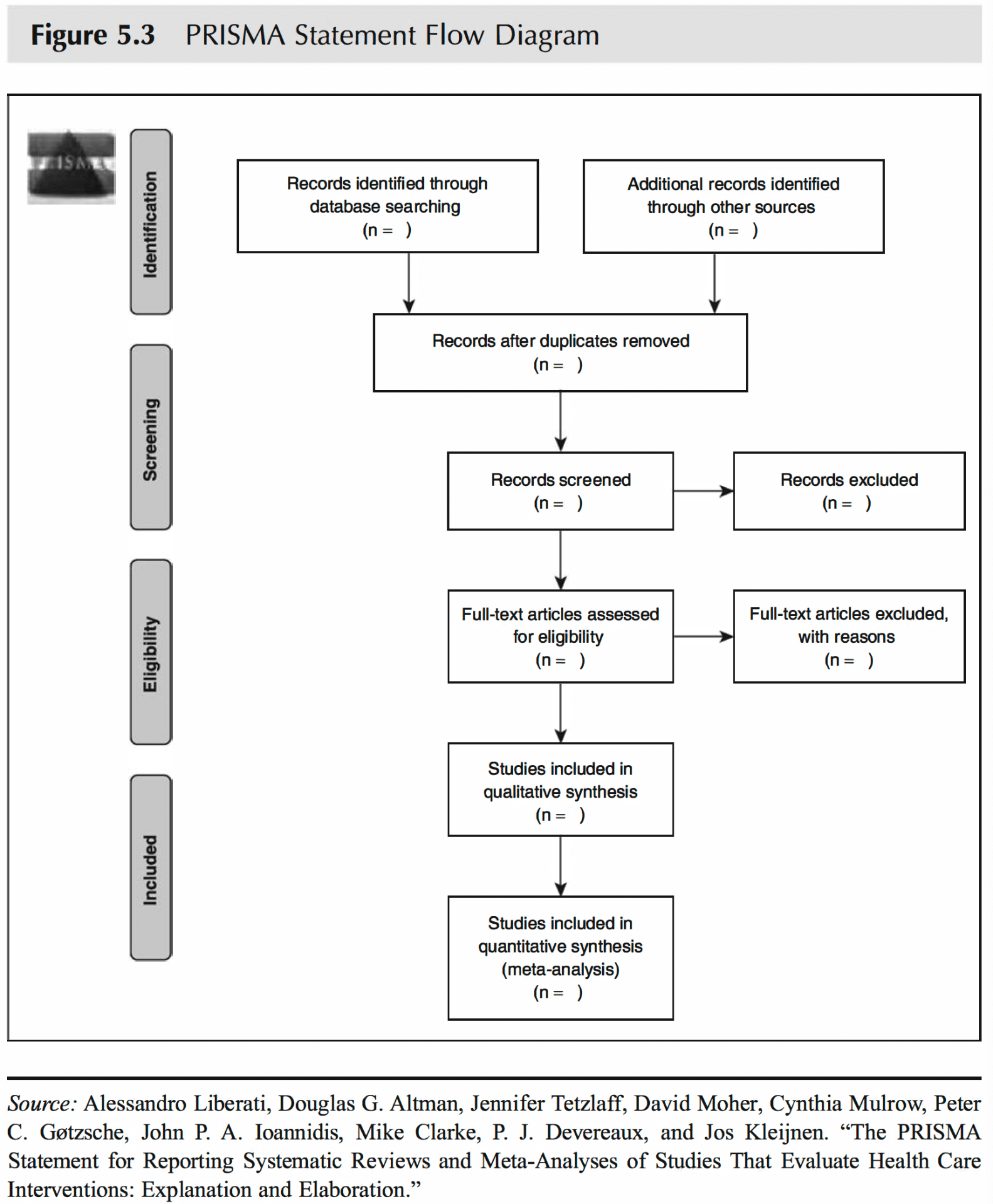

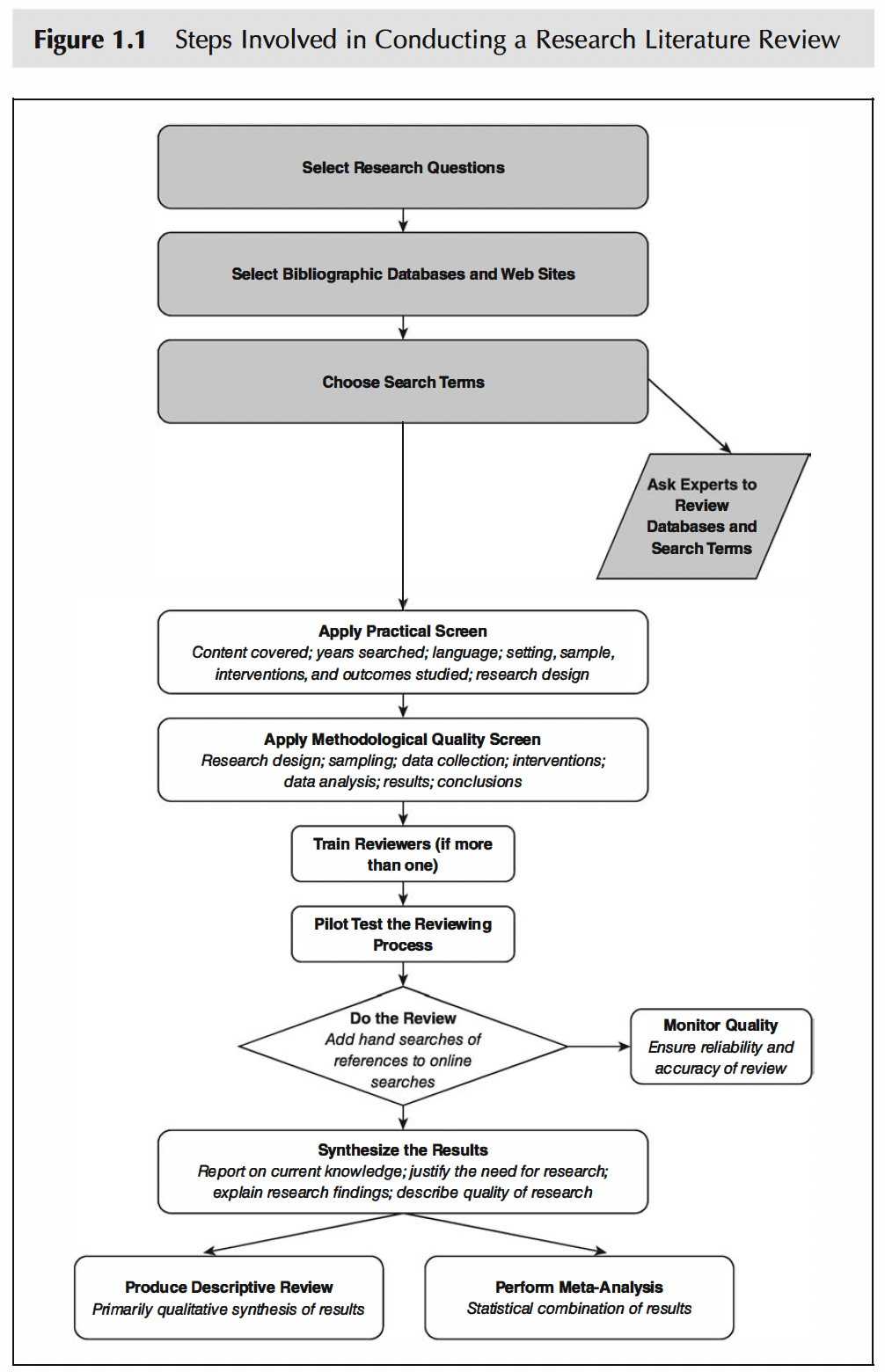

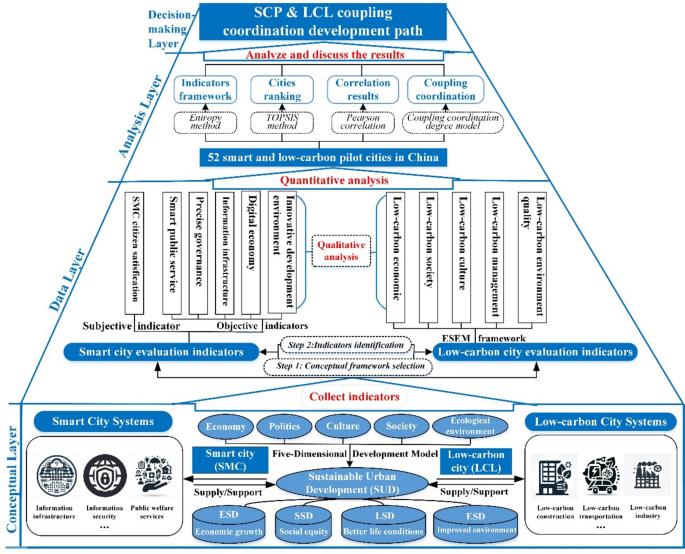

Steps Involved in Conducting a Research Literature Review (Fink, 2019)

1. choose a clear research question., 2. use online databases and other resources to find articles and books relevant to your question..

- Google Scholar

- OSU Library

- ERIC. Index to journal articles on educational research and practice.

- PsycINFO . Citations and abstracts for articles in 1,300 professional journals, conference proceedings, books, reports, and dissertations in psychology and related disciplines.

- PubMed . This search system provides access to the PubMed database of bibliographic information, which is drawn primarily from MEDLINE, which indexes articles from about 3,900 journals in the life sciences (e.g., health, medicine, biology).

- Social Sciences Citation Index . A multidisciplinary database covering the journal literature of the social sciences, indexing more than 1,725 journals across 50 social sciences disciplines.

3. Decide on Search Terms.

- Pick words and phrases based on your research question to find suitable materials

- You can start by finding models for your literature review, and search for existing reviews in your field, using “review” and your keywords. This helps identify themes and organizational methods.

- Narrowing your topic is crucial due to the vast amount of literature available. Focusing on a specific aspect makes it easier to manage the number of sources you need to review, as it’s unlikely you’ll need to cover everything in the field.

- Use AND to retrieve a set of citations in which each citation contains all search terms.

- Use OR to retrieve citations that contain one of the specified terms.

- Use NOT to exclude terms from your search.

- Be careful when using NOT because you may inadvertently eliminate important articles. In Example 3, articles about preschoolers and academic achievement are eliminated, but so are studies that include preschoolers as part of a discussion of academic achievement and all age groups.

4. Filter out articles that don’t meet criteria like language, type, publication date, and funding source.

- Publication language Example. Include only studies in English.

- Journal Example. Include all education journals. Exclude all medical journals.

- Author Example. Include all articles by Andrew Hayes.

- Setting Example. Include all studies that take place in family settings. Exclude all studies that take place in the school setting.

- Participants or subjects Example. Include children that are younger than 6 years old.

- Program/intervention Example. Include all programs that are teacher-led. Exclude all programs that are learner-initiated.

- Research design Example. Include only longitudinal studies. Exclude cross-sectional studies.

- Sampling Example. Include only studies that rely on randomly selected participants.

- Date of publication Example. Include only studies published from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2023.

- Date of data collection Example. Include only studies that collected data from 2010 through 2023. Exclude studies that do not give dates of data collection.

- Duration of data collection Example. Include only studies that collect data for 12 months or longer.

5. Evaluate the methodological quality of the articles, including research design, sampling, data collection, interventions, data analysis, results, and conclusions.

- Maturation: Changes in individuals due to natural development may impact study results, such as intellectual or emotional growth in long-term studies.

- Selection: The method of choosing and assigning participants to groups can introduce bias; random selection minimizes this.

- History: External historical events occurring simultaneously with the study can bias results, making it hard to isolate the study’s effects.

- Instrumentation: Reliable data collection tools are essential to ensure accurate findings, especially in pretest-posttest designs.

- Statistical Regression: Selection based on extreme initial measures can lead to misleading results due to regression towards the mean.

- Attrition: Loss of participants during a study can bias results if those remaining differ significantly from those who dropped out.

- Reactive Effects of Testing: Pre-intervention measures can sensitize participants to the study’s aims, affecting outcomes.

- Interactive Effects of Selection: Unique combinations of intervention programs and participants can limit the generalizability of findings.

- Reactive Effects of Innovation: Artificial experimental environments can lead to uncharacteristic behavior among participants.

- Multiple-Program Interference: Difficulty in isolating an intervention’s effects due to participants’ involvement in other activities or programs.

- Simple Random Sampling : Every individual has an equal chance of being selected, making this method relatively unbiased.

- Systematic Sampling : Selection is made at regular intervals from a list, such as every sixth name from a list of 3,000 to obtain a sample of 500.

- Stratified Sampling : The population is divided into subgroups, and random samples are then taken from each subgroup.

- Cluster Sampling : Natural groups (like schools or cities) are used as batches for random selection, both at the group and individual levels.

- Convenience Samples : Selection probability is unknown; these samples are easy to obtain but may not be representative unless statistically validated.

- Study Power: The ability of a study to detect an effect, if present, is known as its power. Power analysis helps identify a sample size large enough to detect this effect.

- Test-Retest Reliability: High correlation between scores obtained at different times, indicating consistency over time.

- Equivalence/Alternate-Form Reliability: The degree to which two different assessments measure the same concept at the same difficulty level.

- Homogeneity: The extent to which all items or questions in a measure assess the same skill, characteristic, or quality.

- Interrater Reliability: Degree of agreement among different individuals assessing the same item or concept.

- Content Validity: Measures how thoroughly and appropriately a tool assesses the skills or characteristics it’s supposed to measure. Face Validity: Assesses whether a measure appears effective at first glance in terms of language use and comprehensiveness. Criterion Validity: Includes predictive validity (forecasting future performance) and concurrent validity (agreement with already valid measures). Construct Validity: Experimentally established to show that a measure effectively differentiates between people with and without certain characteristics.

- Relies on factors like the scale (categorical, ordinal, numerical) of independent and dependent variables, the count of these variables, and whether the data’s quality and characteristics align with the chosen statistical method’s assumptions.

6. Use a standard form for data extraction, train reviewers if needed, and ensure quality.

7. interpret the results, using your experience and the literature’s quality and content. for a more detailed analysis, a meta-analysis can be conducted using statistical methods to combine study results., 8. produce a descriptive review or perform a meta-analysis..

- Example: Bryman, A. (2007). Effective leadership in higher education: A literature review. Studies in higher education, 32(6), 693-710.

- Clarify the objectives of the analysis.

- Set explicit criteria for including and excluding studies.

- Describe in detail the methods used to search the literature.

- Search the literature using a standardized protocol for including and excluding studies.

- Use a standardized protocol to collect (“abstract”) data from each study regarding study purposes, methods, and effects (outcomes).

- Describe in detail the statistical method for pooling results.

- Report results, conclusions, and limitations.

- Example: Yu, Z. (2023). A meta-analysis of the effect of virtual reality technology use in education. Interactive Learning Environments, 31 (8), 4956-4976.

- Essential and Multifunctional Bibliographic Software: Tools like EndNote, ProCite, BibTex, Bookeeper, Zotero, and Mendeley offer more than just digital storage for references; they enable saving and sharing search strategies, directly inserting references into reports and scholarly articles, and analyzing references by thematic content.

- Comprehensive Literature Reviews: Involve supplementing electronic searches with a review of references in identified literature, manual searches of references and journals, and consulting experts for both unpublished and published studies and reports.

- One of the most famous reporting checklists is the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials ( CONSORT ). CONSORT consists of a checklist and flow diagram. The checklist includes items that need to be addressed in the report.

References:

Bryman, A. (2007). Effective leadership in higher education: A literature review. Studies in higher education , 32 (6), 693-710.

Fink, A. (2019). Conducting research literature reviews: From the internet to paper . Sage publications.

Yu, Z. (2023). A meta-analysis of the effect of virtual reality technology use in education. Interactive Learning Environments, 31 (8), 4956-4976.

University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Blackboard Learn

- Interlibrary Loan

- Study Rooms

- University of Arkansas

Literature Reviews

- Qualitative or Quantitative?

- Getting Started

- Finding articles

- Primary sources? Peer-reviewed?

- Review Articles/ Annual Reviews...?

- Books, ebooks, dissertations

Qualitative researchers TEND to:

Researchers using qualitative methods tend to:

- t hink that social sciences cannot be well-studied with the same methods as natural or physical sciences

- feel that human behavior is context-specific; therefore, behavior must be studied holistically, in situ, rather than being manipulated

- employ an 'insider's' perspective; research tends to be personal and thereby more subjective.

- do interviews, focus groups, field research, case studies, and conversational or content analysis.

Image from https://www.editage.com/insights/qualitative-quantitative-or-mixed-methods-a-quick-guide-to-choose-the-right-design-for-your-research?refer-type=infographics

Qualitative Research (an operational definition)

Qualitative Research: an operational description

Purpose : explain; gain insight and understanding of phenomena through intensive collection and study of narrative data

Approach: inductive; value-laden/subjective; holistic, process-oriented

Hypotheses: tentative, evolving; based on the particular study

Lit. Review: limited; may not be exhaustive

Setting: naturalistic, when and as much as possible

Sampling : for the purpose; not necessarily representative; for in-depth understanding

Measurement: narrative; ongoing

Design and Method: flexible, specified only generally; based on non-intervention, minimal disturbance, such as historical, ethnographic, or case studies

Data Collection: document collection, participant observation, informal interviews, field notes

Data Analysis: raw data is words/ ongoing; involves synthesis

Data Interpretation: tentative, reviewed on ongoing basis, speculative

Quantitative researchers TEND to:

Researchers using quantitative methods tend to:

- think that both natural and social sciences strive to explain phenomena with confirmable theories derived from testable assumptions

- attempt to reduce social reality to variables, in the same way as with physical reality

- try to tightly control the variable(s) in question to see how the others are influenced.

- Do experiments, have control groups, use blind or double-blind studies; use measures or instruments.

Quantitative Research (an operational definition)

Quantitative research: an operational description

Purpose: explain, predict or control phenomena through focused collection and analysis of numberical data

Approach: deductive; tries to be value-free/has objectives/ is outcome-oriented

Hypotheses : Specific, testable, and stated prior to study

Lit. Review: extensive; may significantly influence a particular study

Setting: controlled to the degree possible

Sampling: uses largest manageable random/randomized sample, to allow generalization of results to larger populations

Measurement: standardized, numberical; "at the end"

Design and Method: Strongly structured, specified in detail in advance; involves intervention, manipulation and control groups; descriptive, correlational, experimental

Data Collection: via instruments, surveys, experiments, semi-structured formal interviews, tests or questionnaires

Data Analysis: raw data is numbers; at end of study, usually statistical

Data Interpretation: formulated at end of study; stated as a degree of certainty

This page on qualitative and quantitative research has been adapted and expanded from a handout by Suzy Westenkirchner. Used with permission.

Images from https://www.editage.com/insights/qualitative-quantitative-or-mixed-methods-a-quick-guide-to-choose-the-right-design-for-your-research?refer-type=infographics.

- << Previous: Books, ebooks, dissertations

- Last Updated: Sep 5, 2024 4:04 PM

- URL: https://uark.libguides.com/litreview

- See us on Instagram

- Follow us on Twitter

- Phone: 479-575-4104

- Locations and Hours

- UCLA Library

- Research Guides

- Biomedical Library Guides

Systematic Reviews

- Types of Literature Reviews

What Makes a Systematic Review Different from Other Types of Reviews?

- Planning Your Systematic Review

- Database Searching

- Creating the Search

- Search Filters and Hedges

- Grey Literature

- Managing and Appraising Results

- Further Resources

Reproduced from Grant, M. J. and Booth, A. (2009), A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 26: 91–108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

| Aims to demonstrate writer has extensively researched literature and critically evaluated its quality. Goes beyond mere description to include degree of analysis and conceptual innovation. Typically results in hypothesis or mode | Seeks to identify most significant items in the field | No formal quality assessment. Attempts to evaluate according to contribution | Typically narrative, perhaps conceptual or chronological | Significant component: seeks to identify conceptual contribution to embody existing or derive new theory | |

| Generic term: published materials that provide examination of recent or current literature. Can cover wide range of subjects at various levels of completeness and comprehensiveness. May include research findings | May or may not include comprehensive searching | May or may not include quality assessment | Typically narrative | Analysis may be chronological, conceptual, thematic, etc. | |

| Mapping review/ systematic map | Map out and categorize existing literature from which to commission further reviews and/or primary research by identifying gaps in research literature | Completeness of searching determined by time/scope constraints | No formal quality assessment | May be graphical and tabular | Characterizes quantity and quality of literature, perhaps by study design and other key features. May identify need for primary or secondary research |

| Technique that statistically combines the results of quantitative studies to provide a more precise effect of the results | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching. May use funnel plot to assess completeness | Quality assessment may determine inclusion/ exclusion and/or sensitivity analyses | Graphical and tabular with narrative commentary | Numerical analysis of measures of effect assuming absence of heterogeneity | |

| Refers to any combination of methods where one significant component is a literature review (usually systematic). Within a review context it refers to a combination of review approaches for example combining quantitative with qualitative research or outcome with process studies | Requires either very sensitive search to retrieve all studies or separately conceived quantitative and qualitative strategies | Requires either a generic appraisal instrument or separate appraisal processes with corresponding checklists | Typically both components will be presented as narrative and in tables. May also employ graphical means of integrating quantitative and qualitative studies | Analysis may characterise both literatures and look for correlations between characteristics or use gap analysis to identify aspects absent in one literature but missing in the other | |

| Generic term: summary of the [medical] literature that attempts to survey the literature and describe its characteristics | May or may not include comprehensive searching (depends whether systematic overview or not) | May or may not include quality assessment (depends whether systematic overview or not) | Synthesis depends on whether systematic or not. Typically narrative but may include tabular features | Analysis may be chronological, conceptual, thematic, etc. | |

| Method for integrating or comparing the findings from qualitative studies. It looks for ‘themes’ or ‘constructs’ that lie in or across individual qualitative studies | May employ selective or purposive sampling | Quality assessment typically used to mediate messages not for inclusion/exclusion | Qualitative, narrative synthesis | Thematic analysis, may include conceptual models | |

| Assessment of what is already known about a policy or practice issue, by using systematic review methods to search and critically appraise existing research | Completeness of searching determined by time constraints | Time-limited formal quality assessment | Typically narrative and tabular | Quantities of literature and overall quality/direction of effect of literature | |

| Preliminary assessment of potential size and scope of available research literature. Aims to identify nature and extent of research evidence (usually including ongoing research) | Completeness of searching determined by time/scope constraints. May include research in progress | No formal quality assessment | Typically tabular with some narrative commentary | Characterizes quantity and quality of literature, perhaps by study design and other key features. Attempts to specify a viable review | |

| Tend to address more current matters in contrast to other combined retrospective and current approaches. May offer new perspectives | Aims for comprehensive searching of current literature | No formal quality assessment | Typically narrative, may have tabular accompaniment | Current state of knowledge and priorities for future investigation and research | |

| Seeks to systematically search for, appraise and synthesis research evidence, often adhering to guidelines on the conduct of a review | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching | Quality assessment may determine inclusion/exclusion | Typically narrative with tabular accompaniment | What is known; recommendations for practice. What remains unknown; uncertainty around findings, recommendations for future research | |

| Combines strengths of critical review with a comprehensive search process. Typically addresses broad questions to produce ‘best evidence synthesis’ | Aims for exhaustive, comprehensive searching | May or may not include quality assessment | Minimal narrative, tabular summary of studies | What is known; recommendations for practice. Limitations | |

| Attempt to include elements of systematic review process while stopping short of systematic review. Typically conducted as postgraduate student assignment | May or may not include comprehensive searching | May or may not include quality assessment | Typically narrative with tabular accompaniment | What is known; uncertainty around findings; limitations of methodology | |

| Specifically refers to review compiling evidence from multiple reviews into one accessible and usable document. Focuses on broad condition or problem for which there are competing interventions and highlights reviews that address these interventions and their results | Identification of component reviews, but no search for primary studies | Quality assessment of studies within component reviews and/or of reviews themselves | Graphical and tabular with narrative commentary | What is known; recommendations for practice. What remains unknown; recommendations for future research |

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Planning Your Systematic Review >>

- Last Updated: Jul 23, 2024 3:40 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucla.edu/systematicreviews

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Write for Us

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 21, Issue 4

- How to appraise quantitative research

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

This article has a correction. Please see:

- Correction: How to appraise quantitative research - April 01, 2019

- Xabi Cathala 1 ,

- Calvin Moorley 2

- 1 Institute of Vocational Learning , School of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University , London , UK

- 2 Nursing Research and Diversity in Care , School of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University , London , UK

- Correspondence to Mr Xabi Cathala, Institute of Vocational Learning, School of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University London UK ; cathalax{at}lsbu.ac.uk and Dr Calvin Moorley, Nursing Research and Diversity in Care, School of Health and Social Care, London South Bank University, London SE1 0AA, UK; Moorleyc{at}lsbu.ac.uk

https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2018-102996

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

Some nurses feel that they lack the necessary skills to read a research paper and to then decide if they should implement the findings into their practice. This is particularly the case when considering the results of quantitative research, which often contains the results of statistical testing. However, nurses have a professional responsibility to critique research to improve their practice, care and patient safety. 1 This article provides a step by step guide on how to critically appraise a quantitative paper.

Title, keywords and the authors

The authors’ names may not mean much, but knowing the following will be helpful:

Their position, for example, academic, researcher or healthcare practitioner.

Their qualification, both professional, for example, a nurse or physiotherapist and academic (eg, degree, masters, doctorate).

This can indicate how the research has been conducted and the authors’ competence on the subject. Basically, do you want to read a paper on quantum physics written by a plumber?

The abstract is a resume of the article and should contain:

Introduction.

Research question/hypothesis.

Methods including sample design, tests used and the statistical analysis (of course! Remember we love numbers).

Main findings.

Conclusion.

The subheadings in the abstract will vary depending on the journal. An abstract should not usually be more than 300 words but this varies depending on specific journal requirements. If the above information is contained in the abstract, it can give you an idea about whether the study is relevant to your area of practice. However, before deciding if the results of a research paper are relevant to your practice, it is important to review the overall quality of the article. This can only be done by reading and critically appraising the entire article.

The introduction

Example: the effect of paracetamol on levels of pain.

My hypothesis is that A has an effect on B, for example, paracetamol has an effect on levels of pain.

My null hypothesis is that A has no effect on B, for example, paracetamol has no effect on pain.

My study will test the null hypothesis and if the null hypothesis is validated then the hypothesis is false (A has no effect on B). This means paracetamol has no effect on the level of pain. If the null hypothesis is rejected then the hypothesis is true (A has an effect on B). This means that paracetamol has an effect on the level of pain.

Background/literature review

The literature review should include reference to recent and relevant research in the area. It should summarise what is already known about the topic and why the research study is needed and state what the study will contribute to new knowledge. 5 The literature review should be up to date, usually 5–8 years, but it will depend on the topic and sometimes it is acceptable to include older (seminal) studies.

Methodology

In quantitative studies, the data analysis varies between studies depending on the type of design used. For example, descriptive, correlative or experimental studies all vary. A descriptive study will describe the pattern of a topic related to one or more variable. 6 A correlational study examines the link (correlation) between two variables 7 and focuses on how a variable will react to a change of another variable. In experimental studies, the researchers manipulate variables looking at outcomes 8 and the sample is commonly assigned into different groups (known as randomisation) to determine the effect (causal) of a condition (independent variable) on a certain outcome. This is a common method used in clinical trials.

There should be sufficient detail provided in the methods section for you to replicate the study (should you want to). To enable you to do this, the following sections are normally included:

Overview and rationale for the methodology.

Participants or sample.

Data collection tools.

Methods of data analysis.

Ethical issues.

Data collection should be clearly explained and the article should discuss how this process was undertaken. Data collection should be systematic, objective, precise, repeatable, valid and reliable. Any tool (eg, a questionnaire) used for data collection should have been piloted (or pretested and/or adjusted) to ensure the quality, validity and reliability of the tool. 9 The participants (the sample) and any randomisation technique used should be identified. The sample size is central in quantitative research, as the findings should be able to be generalised for the wider population. 10 The data analysis can be done manually or more complex analyses performed using computer software sometimes with advice of a statistician. From this analysis, results like mode, mean, median, p value, CI and so on are always presented in a numerical format.

The author(s) should present the results clearly. These may be presented in graphs, charts or tables alongside some text. You should perform your own critique of the data analysis process; just because a paper has been published, it does not mean it is perfect. Your findings may be different from the author’s. Through critical analysis the reader may find an error in the study process that authors have not seen or highlighted. These errors can change the study result or change a study you thought was strong to weak. To help you critique a quantitative research paper, some guidance on understanding statistical terminology is provided in table 1 .

- View inline

Some basic guidance for understanding statistics

Quantitative studies examine the relationship between variables, and the p value illustrates this objectively. 11 If the p value is less than 0.05, the null hypothesis is rejected and the hypothesis is accepted and the study will say there is a significant difference. If the p value is more than 0.05, the null hypothesis is accepted then the hypothesis is rejected. The study will say there is no significant difference. As a general rule, a p value of less than 0.05 means, the hypothesis is accepted and if it is more than 0.05 the hypothesis is rejected.

The CI is a number between 0 and 1 or is written as a per cent, demonstrating the level of confidence the reader can have in the result. 12 The CI is calculated by subtracting the p value to 1 (1–p). If there is a p value of 0.05, the CI will be 1–0.05=0.95=95%. A CI over 95% means, we can be confident the result is statistically significant. A CI below 95% means, the result is not statistically significant. The p values and CI highlight the confidence and robustness of a result.

Discussion, recommendations and conclusion

The final section of the paper is where the authors discuss their results and link them to other literature in the area (some of which may have been included in the literature review at the start of the paper). This reminds the reader of what is already known, what the study has found and what new information it adds. The discussion should demonstrate how the authors interpreted their results and how they contribute to new knowledge in the area. Implications for practice and future research should also be highlighted in this section of the paper.

A few other areas you may find helpful are:

Limitations of the study.

Conflicts of interest.

Table 2 provides a useful tool to help you apply the learning in this paper to the critiquing of quantitative research papers.

Quantitative paper appraisal checklist

- 1. ↵ Nursing and Midwifery Council , 2015 . The code: standard of conduct, performance and ethics for nurses and midwives https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/nmc-publications/nmc-code.pdf ( accessed 21.8.18 ).

- Gerrish K ,

- Moorley C ,

- Tunariu A , et al

- Shorten A ,

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent Not required.

Provenance and peer review Commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Correction notice This article has been updated since its original publication to update p values from 0.5 to 0.05 throughout.

Linked Articles

- Miscellaneous Correction: How to appraise quantitative research BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and RCN Publishing Company Ltd Evidence-Based Nursing 2019; 22 62-62 Published Online First: 31 Jan 2019. doi: 10.1136/eb-2018-102996corr1

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Methods for Quantitative Research in Psychology

- Conducting Research

Psychological Research

August 2023

This seven-hour course provides a comprehensive exploration of research methodologies, beginning with the foundational steps of the scientific method. Students will learn about hypotheses, experimental design, data collection, and the analysis of results. Emphasis is placed on defining variables accurately, distinguishing between independent, dependent, and controlled variables, and understanding their roles in research.

The course delves into major research designs, including experimental, correlational, and observational studies. Students will compare and contrast these designs, evaluating their strengths and weaknesses in various contexts. This comparison extends to the types of research questions scientists pose, highlighting how different designs are suited to different inquiries.

A critical component of the course is developing the ability to judge the quality of sources for literature reviews. Students will learn criteria for evaluating the credibility, relevance, and reliability of sources, ensuring that their understanding of the research literature is built on a solid foundation.

Reliability and validity are key concepts addressed in the course. Students will explore what it means for an observation to be reliable, focusing on consistency and repeatability. They will also compare and contrast different forms of validity, such as internal, external, construct, and criterion validity, and how these apply to various research designs.

The course concepts are thoroughly couched in examples drawn from the psychological research literature. By the end of the course, students will be equipped with the skills to design robust research studies, critically evaluate sources, and understand the nuances of reliability and validity in scientific research. This knowledge will be essential for conducting high-quality research and contributing to the scientific community.

Learning objectives

- Describe the steps of the scientific method.

- Specify how variables are defined.

- Compare and contrast the major research designs.

- Explain how to judge the quality of a source for a literature review.

- Compare and contrast the kinds of research questions scientists ask.

- Explain what it means for an observation to be reliable.

- Compare and contrast forms of validity as they apply to the major research designs.

This program does not offer CE credit.

More in this series

Introduces applying statistical methods effectively in psychology or related fields for undergraduates, high school students, and professionals.

August 2023 On Demand Training

Introduces the importance of ethical practice in scientific research for undergraduates, high school students, and professionals.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

Quantitative reviewing: the literature review as scientific inquiry

- PMID: 6869492

- DOI: 10.5014/ajot.37.5.313

The literature review process is conceptualized as a form of scientific inquiry that involves methodological requirements and inferences similar to those employed in primary research. Five stages of quantitative reviewing that parallel stages in primary investigation are identified and briefly described. They include problem formation, data collection, data evaluation, analysis and interpretation, and reporting the results. The first two stages provide information and guidelines relevant to reviewers' employing traditional narrative procedures or conducting reviews of qualitative research literature. The final three stages relate specifically to the methodology of quantitative reviewing. The argument is made that quantitative reviewing procedures represent a paradigm shift that can assist researchers and clinicians in occupational therapy to establish a scientific data base that will serve to guide theory development and validate clinical practice.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Quantitative reviewing of medical literature. An approach to synthesizing research results in clinical pediatrics. Ottenbacher KJ, Petersen P. Ottenbacher KJ, et al. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1984 Aug;23(8):423-7. doi: 10.1177/000992288402300801. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1984. PMID: 6734016

- Reviewing the methodology of an integrative review. Hopia H, Latvala E, Liimatainen L. Hopia H, et al. Scand J Caring Sci. 2016 Dec;30(4):662-669. doi: 10.1111/scs.12327. Epub 2016 Apr 14. Scand J Caring Sci. 2016. PMID: 27074869 Review.

- Evidence-based medicine, systematic reviews, and guidelines in interventional pain management: part 6. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies. Manchikanti L, Datta S, Smith HS, Hirsch JA. Manchikanti L, et al. Pain Physician. 2009 Sep-Oct;12(5):819-50. Pain Physician. 2009. PMID: 19787009

- Translational Metabolomics of Head Injury: Exploring Dysfunctional Cerebral Metabolism with Ex Vivo NMR Spectroscopy-Based Metabolite Quantification. Wolahan SM, Hirt D, Glenn TC. Wolahan SM, et al. In: Kobeissy FH, editor. Brain Neurotrauma: Molecular, Neuropsychological, and Rehabilitation Aspects. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; 2015. Chapter 25. In: Kobeissy FH, editor. Brain Neurotrauma: Molecular, Neuropsychological, and Rehabilitation Aspects. Boca Raton (FL): CRC Press/Taylor & Francis; 2015. Chapter 25. PMID: 26269925 Free Books & Documents. Review.

- Association between pacifier use and breast-feeding, sudden infant death syndrome, infection and dental malocclusion. Callaghan A, Kendall G, Lock C, Mahony A, Payne J, Verrier L. Callaghan A, et al. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2005 Jul;3(6):147-67. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-6988.2005.00024.x. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2005. PMID: 21631747

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Silverchair Information Systems

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources