Revising and Editing for Creative Writers

Sean Glatch | October 2, 2023 | Leave a Comment

Want to learn more about revising and editing? Check out our self-paced class The Successful Novel , which gives you the tools to write, revise, and publish the novel waiting to be written inside you.

Although the terms revising and editing are often used interchangeably, stylish writers know the difference between revising and editing. When it’s time to shape a first draft into a polished, publishable piece of writing, knowing how to both revise and edit your work is essential.

So, what is revising vs editing? Revising refers to global changes in the text—significant amendments to the work’s structure, intent, themes, content, organization, etc. These are, in other words, macro-level considerations. Editing, by contrast, focuses on changes at the word, sentence, and paragraph level.

These two concepts require different skills and attentions, but both are necessary to create a finished piece of writing. So, let’s dive deeper into revising vs editing, including a revising and editing checklist you can use for any passage of poetry or prose.

First, let’s dive a little deeper into these two essential skills. What is the difference between revising and editing?

Note: the revising and editing resources in this article are geared towards fiction writers. Nonetheless, much of this advice also applies to essayists and nonfiction writers, too.

Revising and Editing: Contents

- The focus of revision

- The focus of editing

Revising Vs Editing: Venn Diagram

- Revision Strategies

- Editing Strategies

- Strategies for Revising and Editing

Revising and Editing Checklist

What is the difference between revising and editing.

Revising and editing are different types of changes you can make to a text. “Revising” is concerned with macro-level considerations: the ideas of a text, and how they are organized and structured as a whole. “Editing,” by contrast, concerns itself with micro-level stylistic considerations, the words and sentences that get those macro-level ideas across.

Revising is concerned with the ideas and structure of the text as a whole; editing is concerned with stylistic considerations, like word choice and sentence structure.

This revising vs editing chart outlines the different considerations for each concept:

| What do I want my reader to understand? Why am I writing this? | Is every word necessary? Is every word the best possible word? Do I need to omit needless words? |

| What ideas does the text try to get across? How do those themes recur throughout the text? | Does this kind of sentence best communicate the ideas within it? |

| How is the text structured? How are ideas interwoven in the text? What does each chapter or section advance the overall themes and intentions of the text? Do I have a good balance of scene and summary? | Are ideas repeated in such a way that they cement ideas for the reader? Are any repetitions redundant? |

| How do the actions of characters within the story structure the story itself? How do those actions foreshadow events to come? | Does the writing create a sensory experience? Does it demonstrate ideas, or simply feed them to the reader? |

| What tone does the text, as a whole, take towards its various themes and ideas? | Are ideas clear at the word, sentence, and paragraph level? Can they be clearer? |

| What atmospheres does the text, as a whole, contain? What emotions does the text evoke? | Does the writing carry forth its different themes and ideas continuously? Does any part of the text not contribute to the overall purpose of the text? |

| Who are the people populating the text? What does their look like? How do their shape the narrative? | Do the devices used demonstrate the ideas in fresh, clear, or useful ways? Do they contribute to the writing? Am I spare but precise with ? |

| What does each setting represent in the story? How does the setting impact the narrative? | Does the text seamlessly transition from one idea to the next? |

| Who is narrating the story? What is their perspective? Do they have flaws, blindspots, or opinions? Do they try to influence the reader’s perspective? | If the text contains dialogue, does the dialogue sound like the way the character speaks? Does that character sound real? |

| Does the text utilize the same style throughout, or does the style vary in accordance with the message and intent of the text? | Does the writing sound good? Does it flow? Will the reader be able to hear my voice in the text? |

Let’s go a bit deeper into these revising and editing concepts.

Revision strategies focus on:

The text as a whole. If revision focuses on the macro-level concerns for the text, then revision strategies for writing require the writer to think about what the text is accomplishing.

In large part, this means thinking about themes, ideas, arguments, structures, and, if the text is fiction, the elements of fiction themselves. You might also consider how the text is influenced by other writers and media, or what philosophies are operating within the text.

Here are some questions to ask when revising your work:

- Does the writing begin at the beginning?

- Are the ideas logically sequenced?

- How are different ideas juxtaposed? How does their juxtaposition alter the message of the text?

- What messages are present in the text?

- How do the characters of the text represent different ideas and messages?

- What do the different settings of the story represent? How does the setting impact the decisions that characters make?

- What core conflicts shape the plot?

- Who is the narrator? How does their point of view impact the story being told?

- What attitude do I take towards the various themes and ideas? Is that attitude present?

- Does the writing use scenes to showcase important moments, and summaries to glide over less important passages of time?

- What atmosphere(s) are in the text? Does the story’s mood complement the story itself?

- Does the story have a clearly defined climax? What questions does (and doesn’t) the climax resolve?

- What transformation occurs in the story? How are the characters at the end different than at the beginning?

- Does the writing end at the ending? Is the ending a closed door, or (preferably) an open one?

Editing strategies focus on:

The words and sentences. In contrast to revision strategies, editing strategies ask the writer to examine how the text is accomplishing macro-level concerns.

This means getting into the weeds with language. Small decisions, like the use of a synonym or the arrangement of certain sounds, stack up to create an enjoyable story. Moreover, good writing at the sentence level makes it easier to produce good writing at the global level.

Here are some questions to ask when editing your work:

- Is this the right word to describe a certain image, idea, or sensation?

- Do my sentences have enough variation in length and structure?

- Are the words I use easy to understand? If I use jargon or academic language, is the meaning of the text still clear?

- Do I use active vs passive voice with intent?

- Have I omitted any unnecessary words?

- How does it sound to read my work aloud? Does it flow like it should?

- Do I use sonic and poetic devices , like alliteration, consonance, assonance, and internal rhyme, to make the writing more enjoyable? Do those devices enhance the text?

- How does the text transition between scenes and ideas? Do these transitions enhance the logical flow of plot and ideas?

- Do I repeat certain words a lot? Do those repetitions contribute to the text, or do they become redundant?

- Have I employed the “show, don’t tell” rule consistently in my writing? Do I have a good balance of showing and telling?

- Do I use metaphors, similes, and analogies to illustrate important ideas in new and thought-provoking ways?

- Is the writing clear at the word, sentence, and paragraph level?

- Does the dialogue sound like it was spoken by a real person? Does each character have a distinct voice, separate from the voice of the author?

Note: editing does not include proofreading. Proofreading is something you typically do once the final draft is done. It is the process of making sure there are no typos, misspellings, misplaced punctuation marks, or grammatical errors. Do this once you’ve thoroughly covered revising and editing.

Now, let’s take a closer look at each of these skills.

Revising Vs Editing: Revision Strategies for Writing

In addition to asking the above questions, here are some revision strategies to help you tackle the macro-level concerns in your writing.

Revision Strategies: Take a break after drafting

Before you get to revising and editing your work, take a break when you’ve finished the first draft. It is much easier to revise and edit when you can look at your work with a fresh set of eyes.

How long should you wait? It really depends. Some authors give their work 2 or 4 weeks. Stephen King recommends a 6 week break in his book On Writing . Really, you should give yourself enough time to forget the finer details of your work, but not so much time that you lose passion for the project.

Revision Strategies: Write a memory draft

Here’s a crazy idea: when you’re done with your first draft, throw it out.

Right. Don’t save a copy. Don’t reread what you’ve written. Don’t give yourself any access to it. Once you’ve written the final word, delete everything.

Why would you do this? Some writers, called “pantsers” or “discovery writers”, don’t plot in advance, they just write from scratch and figure it out as they go. When you delete this draft, you’re forced to write it again from memory. This “memory draft” will be written from only the most salient parts of the first draft—the parts that were memorable, enjoyable, and essential to the work.

Of course, you can write a memory draft without deleting your first draft. Deleting the first draft just makes it easier to ensure you never go back. This approach is not for everyone, but for some writers, such as our instructor Sarah Aronson , it results in the strongest possible work.

Revision Strategies: Create a plot line

If you’re a pantser, or even if you plot everything in advance, return to your work by creating a plot line.

Go scene by scene. What is every action that drives the writing forward? Who are the characters involved? Are those actions consistent with the characters?

Also give consideration to different plot structures. What plot structure does the story use? Is there a main plot and subplot(s)? How do the subplots tie into the plot as a whole?

Plot lines help you zoom out. Seeing your work at the macro-level is the key difference between revising and editing; to revise your work, you must be able to see it from a distance before zooming in closer.

Revision Strategies: Funneling

Funneling is a process for zooming into the work from a distance. It asks you to get progressively more in-the-weeds with your writing.

First, you need to look at the work as a whole. What are the overall themes and messages? What does the work accomplish, or try to accomplish? How is the work structured? Does the work feel essential?

Then, zoom in, and ask those same questions at the various sublevels of the work. Ask these questions by section, by chapter, by scene, by paragraph, and even sentence by sentence. Evaluating the purpose of each individual component helps you decide what to keep, what to cut, and what to revise and edit.

Revision Strategies: Look for discontinuities

Another way to decide what to keep, cut, revise and edit, is to spend time intentionally searching for discontinuities.

What are discontinuities? These are parts of the text where the writing is not continuous. They can be caused by the following:

- Sections of the text that don’t ultimately contribute to the plot, subplots, characters, character development, setting, etc.

- Plot threads that haven’t yet been tied up, but need to be.

- Subplots that ultimately do not impact the main plot of the story.

- Gaps in plot or characterization that need to be filled for the story to make sense.

Some discontinuities are intentional, and writers should certainly lean into ambiguity and interpretation. But your story should also say everything it needs to. Discontinuities hinder a story’s ability to do this. By snuffing them out and fixing them, you can prepare a text that is much more ready for editing.

Revising Vs Editing: Editing Strategies for Writing

In addition to asking the previous questions we’ve listed for editing your work, here are some editing strategies to help you tackle the micro-level concerns in your writing.

Editing Strategies: Read it out loud

Yes, even if it’s novel-length. Reading your work out loud is essential to honing your prose. (This is also true for writing poetry !)

The way that writing flows in your head is not necessarily how it flows when spoken aloud. As a result, your writing might sound good when you read it, but not when you say it. Writing that sounds good out loud always sounds good on the page; writing that sounds clunky or hard to follow out loud might be read the same way.

In addition to catching opportunities for stylistic improvement, reading your work out loud also gives you a chance to experience your work in a different way. You might gain a new perspective that helps you tackle major revisions.

Editing Strategies: Focus on specificity

Ambiguity has its place in literature. But, when it comes to giving good detail and description, specificity is key.

Take this passage, from The Mayor of Casterbridge by Thomas Hardy:

“Having sufficiently rested they proceeded on their way at evenfall. The dense trees of the avenue rendered the road dark as a tunnel, though the open land on each side was still under a faint daylight. In other words, they passed down a midnight between two gloamings.”

Look at how the attention to detail in this passage paints such a dazzling image. I can see this picture moving in my mind’s eye. And, the phrase “a midnight between two gloamings” is both poetic and musical, making this excerpt an all around enjoyable read.

What would a nonspecific passage of text look like? Instead of the above, imagine Hardy writing “The road was shady.” Maybe you can picture that in your head, but does the image move? Do you know that the shade is provided by trees, as opposed to buildings? Does it even matter whether the road was shady or not?

You don’t need to make everything specific, but specificity helps draw the reader’s attention to what’s beautiful and important. Through specificity, writers can access something both stimulating and poetic for the reader. Use this tool whenever you want to draw the mind’s eye somewhere.

Editing Strategies: Omit needless words

Omitting needless words is central to the art of editing. If a word isn’t doing important work, or if there is a less wordy way to say something, cut it out of the text. Be heartless!

Your style will always be improved by concision. Not brevity, but concision —where every word does important, necessary work. A sentence can be 200 words long, so long as every word is essential.

Common words to omit include adverbs, undescriptive adjectives, passive phrases that are better off active, and prepositions in place of stronger verbs. For more tips, check out our article on this topic:

https://writers.com/concise-writing

Editing Strategies: Turn repetition into variety

Repetition is a useful stylistic device to emphasize the important ideas and images in a text. But, repetition should be used sparingly. To keep your writing fresh and engaging, try not to repeat yourself too much, and call out parts of your text where you do.

This is true at both the word and sentence level. At the word level, keep things visually interesting. If a lot of things in your scene are already yellow, then the building can be green, for example. Also be sure to vary your transition words. If you use “then” to move to every next scene, the reader will catch on and get annoyed, quickly.

At the sentence level, vary your sentence lengths and structures. A series of short sentences will start to sound staccato. Too many long sentences will tax the reader’s attention. Sentences of any length can be used in any way. But, as a quick guide, you can often use short sentences to convey brief summary or information, medium sentences to advance the narrative, and long sentences for moments of introspection or important description. Again, any sentence of any length can do any of those things, but that’s an easy rule to start from.

Even at the paragraph level, try to have a mix of long and short paragraphs, where you can. Also, try to include dialogue at regular intervals. If your characters haven’t spoken for at least 3 pages, let their voices onto the page.

Editing Strategies: Ask yourself, who does your writing sound like?

This is an important question to ask when you’re editing your work. Who does your writing sound like?

It is important to define this, because you want the writing to sound like it’s coming from a real person. If you’re writing nonfiction, then you obviously want the writing to sound like yourself.

When writing fiction, the writing may sound like yourself, but remember, the narrator is not necessarily the author. So, the text should sound like whoever is narrating the story, even if it has some stylistic consistencies with other fiction you’ve written.

What you absolutely do not want is to affect a lofty manner. You can be artful, musical, poetic even, but you absolutely cannot Sound Like A Writer. Using elaborate sentence structures, academic vocabulary, or else trying to write High Literature will only make your writing sound pretentious. Talk to your reader, not above them.

Also, be sure to know the warning signs of when a passage of text is purple prose .

Revising and Editing Strategies

These strategies are useful for both revising and editing. As you revise and edit your work, consider doing the following:

Revising and Editing: Read like a writer

The best way to improve as a writer is to read other writers like a writer yourself. This is invaluable advice, especially for anyone learning how to write a novel . Paying attention to the craft skills that go into a work of literature will help you think about the decisions you make in your own work.

You can do this at both a revising and editing level. How did the author structure their text? Why does the chapter end here? What did they intend to do by using that specific word choice? Why is this sentence so long?

When you make a practice of doing this, it is much easier to bring that practice into your own work.

Learn more about reading like a writer here:

https://writers.com/how-to-read-like-a-writer

Revising and Editing: Print it out

Most people these days write using a computer. (I say most, because our instructor Troy Wilderson writes her novels freehand.) Whatever medium you use to write, try using a different medium to revise and edit.

So, if you typed your first draft, print it out and mark up the physical pages. If you happened to write freehand or use a typewriter, type up those pages and revise from there.

The point is to think about your work in a different medium. Revising and editing with different technology helps shift the gears in your brain, and it also encourages you to see your work with a different perspective. For whatever reason, you’ll think about your work with a fresh set of eyes if it’s sitting in front of you in a different format.

And, if you don’t have access to a printer, at least put your writing in a different text editor. Move from Microsoft Word to Google Docs, or even use a novel editing software like Scrivener . Anything to get you out of writing mode, and into revising mode, allowing you to see your work from a new angle.

Revising and Editing: Don’t do it all at once

Writing is a marathon, not a sprint. The same holds true for revising and editing.

If you try to tackle it all at once, you will create three problems for yourself.

One, you will rush through a process that requires slow, methodical labor. Trying to tackle everything right away will result in a work that’s fundamentally incomplete.

Two, you will end up ignoring or neglecting important or powerful opportunities for revision. Taking things slow helps you think more clearly about your work. You might miss out on powerful insights by trying to accomplish everything right away. You might also force yourself to avoid the work that needs to be done, such as major revisions or a full scale rewrite.

Three, you miss out on the joy of revising and editing. This is a fundamentally fun experience. It is also an experience central to being an author. Let yourself have it.

Revising and Editing: Read in reverse

Try reading your work from end to beginning. Read each sentence left to right, but read the sentences from back to front.

This might seem a little strange. After all, won’t you lose the meaning of the sentences by doing this? Well, that’s exactly the point—reading in reverse allows you to see the text in a new light. You might notice a sentence that is far less musical when it stands on its own. Or, you might find information that’s been unnecessarily repeated. At the structural level, you might realize that certain passages, sections, or scenes are too close to the end (or middle, or beginning) of the text.

This is another effort to see your work in a new light. Taking as many opportunities as you can to do this will inevitably result in a stronger, more satisfying story.

Revising and Editing: Get feedback

When you’ve reached the limit of what you can accomplish yourself, it’s time to get feedback on your work.

The important thing is knowing when you’ve reached this limit . Most people should not seek feedback when they’ve finished the first draft. Why? Because the work is in a far more vulnerable state. You need to give yourself time to revise and edit using only your own expertise.

In other words, you need to bring the work much closer to your vision for the work before other people see it. Letting people in too early could result in feedback that changes the story as a whole, and brings it further away from the vision you have for it.

Give yourself a few revisions before you start getting feedback on your work. Trust in your own instinct and artistic vision. Feedback should help you reach that vision; anything that alters it doesn’t belong in the final draft.

Here are some things to ask yourself in both the revising and editing stages of your work.

- Does the writing begin where it should?

- Does the juxtaposition of different ideas enhance those ideas?

- Do the characters of the text represent different ideas and messages?

- Do the settings represent certain themes and ideas?

- Do the settings impact the characters’ decisions?

- Is the plot shaped by conflict?

- Is the narrator clearly defined?

- Does the story’s mood complement the story itself?

- Does the story have a clearly defined climax?

- Do certain characters transform by the end of the story? (If not, is that intentional?)

- Is every word the right word to describe a certain image, idea, or sensation?

- Does my writing flow when spoken out loud?

- Do I use sonic devices to make the writing more enjoyable? Do those devices enhance the text?

- Do transitions enhance the logical flow of plot and ideas?

- Have I employed the “show, don’t tell” rule consistently in my writing?

- Do I have a good balance of showing and telling?

- Do I use metaphors, similes, and analogies to illustrate ideas in thought-provoking ways?

- Does the dialogue sound like it was spoken by a real person?

- Does each character have a distinct voice, separate from the voice of the author?

Get Tips for Revising and Editing Your Work at Writers.com

Revising and editing your work isn’t easy. Make it easier with feedback from the instructors at Writers.com. Take a look at our upcoming online writing classes , where you’ll receive expert guidance and instruction from our roster of successful, stylish authors.

Sean Glatch

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Revising Drafts

Rewriting is the essence of writing well—where the game is won or lost. —William Zinsser

What this handout is about

This handout will motivate you to revise your drafts and give you strategies to revise effectively.

What does it mean to revise?

Revision literally means to “see again,” to look at something from a fresh, critical perspective. It is an ongoing process of rethinking the paper: reconsidering your arguments, reviewing your evidence, refining your purpose, reorganizing your presentation, reviving stale prose.

But I thought revision was just fixing the commas and spelling

Nope. That’s called proofreading. It’s an important step before turning your paper in, but if your ideas are predictable, your thesis is weak, and your organization is a mess, then proofreading will just be putting a band-aid on a bullet wound. When you finish revising, that’s the time to proofread. For more information on the subject, see our handout on proofreading .

How about if I just reword things: look for better words, avoid repetition, etc.? Is that revision?

Well, that’s a part of revision called editing. It’s another important final step in polishing your work. But if you haven’t thought through your ideas, then rephrasing them won’t make any difference.

Why is revision important?

Writing is a process of discovery, and you don’t always produce your best stuff when you first get started. So revision is a chance for you to look critically at what you have written to see:

- if it’s really worth saying,

- if it says what you wanted to say, and

- if a reader will understand what you’re saying.

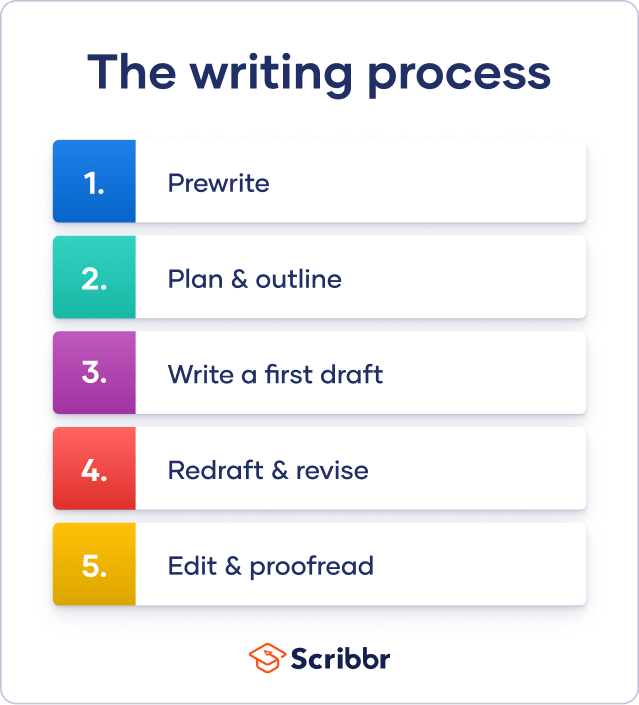

The process

What steps should i use when i begin to revise.

Here are several things to do. But don’t try them all at one time. Instead, focus on two or three main areas during each revision session:

- Wait awhile after you’ve finished a draft before looking at it again. The Roman poet Horace thought one should wait nine years, but that’s a bit much. A day—a few hours even—will work. When you do return to the draft, be honest with yourself, and don’t be lazy. Ask yourself what you really think about the paper.

- As The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers puts it, “THINK BIG, don’t tinker” (61). At this stage, you should be concerned with the large issues in the paper, not the commas.

- Check the focus of the paper: Is it appropriate to the assignment? Is the topic too big or too narrow? Do you stay on track through the entire paper?

- Think honestly about your thesis: Do you still agree with it? Should it be modified in light of something you discovered as you wrote the paper? Does it make a sophisticated, provocative point, or does it just say what anyone could say if given the same topic? Does your thesis generalize instead of taking a specific position? Should it be changed altogether? For more information visit our handout on thesis statements .

- Think about your purpose in writing: Does your introduction state clearly what you intend to do? Will your aims be clear to your readers?

What are some other steps I should consider in later stages of the revision process?

- Examine the balance within your paper: Are some parts out of proportion with others? Do you spend too much time on one trivial point and neglect a more important point? Do you give lots of detail early on and then let your points get thinner by the end?

- Check that you have kept your promises to your readers: Does your paper follow through on what the thesis promises? Do you support all the claims in your thesis? Are the tone and formality of the language appropriate for your audience?

- Check the organization: Does your paper follow a pattern that makes sense? Do the transitions move your readers smoothly from one point to the next? Do the topic sentences of each paragraph appropriately introduce what that paragraph is about? Would your paper work better if you moved some things around? For more information visit our handout on reorganizing drafts.

- Check your information: Are all your facts accurate? Are any of your statements misleading? Have you provided enough detail to satisfy readers’ curiosity? Have you cited all your information appropriately?

- Check your conclusion: Does the last paragraph tie the paper together smoothly and end on a stimulating note, or does the paper just die a slow, redundant, lame, or abrupt death?

Whoa! I thought I could just revise in a few minutes

Sorry. You may want to start working on your next paper early so that you have plenty of time for revising. That way you can give yourself some time to come back to look at what you’ve written with a fresh pair of eyes. It’s amazing how something that sounded brilliant the moment you wrote it can prove to be less-than-brilliant when you give it a chance to incubate.

But I don’t want to rewrite my whole paper!

Revision doesn’t necessarily mean rewriting the whole paper. Sometimes it means revising the thesis to match what you’ve discovered while writing. Sometimes it means coming up with stronger arguments to defend your position, or coming up with more vivid examples to illustrate your points. Sometimes it means shifting the order of your paper to help the reader follow your argument, or to change the emphasis of your points. Sometimes it means adding or deleting material for balance or emphasis. And then, sadly, sometimes revision does mean trashing your first draft and starting from scratch. Better that than having the teacher trash your final paper.

But I work so hard on what I write that I can’t afford to throw any of it away

If you want to be a polished writer, then you will eventually find out that you can’t afford NOT to throw stuff away. As writers, we often produce lots of material that needs to be tossed. The idea or metaphor or paragraph that I think is most wonderful and brilliant is often the very thing that confuses my reader or ruins the tone of my piece or interrupts the flow of my argument.Writers must be willing to sacrifice their favorite bits of writing for the good of the piece as a whole. In order to trim things down, though, you first have to have plenty of material on the page. One trick is not to hinder yourself while you are composing the first draft because the more you produce, the more you will have to work with when cutting time comes.

But sometimes I revise as I go

That’s OK. Since writing is a circular process, you don’t do everything in some specific order. Sometimes you write something and then tinker with it before moving on. But be warned: there are two potential problems with revising as you go. One is that if you revise only as you go along, you never get to think of the big picture. The key is still to give yourself enough time to look at the essay as a whole once you’ve finished. Another danger to revising as you go is that you may short-circuit your creativity. If you spend too much time tinkering with what is on the page, you may lose some of what hasn’t yet made it to the page. Here’s a tip: Don’t proofread as you go. You may waste time correcting the commas in a sentence that may end up being cut anyway.

How do I go about the process of revising? Any tips?

- Work from a printed copy; it’s easier on the eyes. Also, problems that seem invisible on the screen somehow tend to show up better on paper.

- Another tip is to read the paper out loud. That’s one way to see how well things flow.

- Remember all those questions listed above? Don’t try to tackle all of them in one draft. Pick a few “agendas” for each draft so that you won’t go mad trying to see, all at once, if you’ve done everything.

- Ask lots of questions and don’t flinch from answering them truthfully. For example, ask if there are opposing viewpoints that you haven’t considered yet.

Whenever I revise, I just make things worse. I do my best work without revising

That’s a common misconception that sometimes arises from fear, sometimes from laziness. The truth is, though, that except for those rare moments of inspiration or genius when the perfect ideas expressed in the perfect words in the perfect order flow gracefully and effortlessly from the mind, all experienced writers revise their work. I wrote six drafts of this handout. Hemingway rewrote the last page of A Farewell to Arms thirty-nine times. If you’re still not convinced, re-read some of your old papers. How do they sound now? What would you revise if you had a chance?

What can get in the way of good revision strategies?

Don’t fall in love with what you have written. If you do, you will be hesitant to change it even if you know it’s not great. Start out with a working thesis, and don’t act like you’re married to it. Instead, act like you’re dating it, seeing if you’re compatible, finding out what it’s like from day to day. If a better thesis comes along, let go of the old one. Also, don’t think of revision as just rewording. It is a chance to look at the entire paper, not just isolated words and sentences.

What happens if I find that I no longer agree with my own point?

If you take revision seriously, sometimes the process will lead you to questions you cannot answer, objections or exceptions to your thesis, cases that don’t fit, loose ends or contradictions that just won’t go away. If this happens (and it will if you think long enough), then you have several choices. You could choose to ignore the loose ends and hope your reader doesn’t notice them, but that’s risky. You could change your thesis completely to fit your new understanding of the issue, or you could adjust your thesis slightly to accommodate the new ideas. Or you could simply acknowledge the contradictions and show why your main point still holds up in spite of them. Most readers know there are no easy answers, so they may be annoyed if you give them a thesis and try to claim that it is always true with no exceptions no matter what.

How do I get really good at revising?

The same way you get really good at golf, piano, or a video game—do it often. Take revision seriously, be disciplined, and set high standards for yourself. Here are three more tips:

- The more you produce, the more you can cut.

- The more you can imagine yourself as a reader looking at this for the first time, the easier it will be to spot potential problems.

- The more you demand of yourself in terms of clarity and elegance, the more clear and elegant your writing will be.

How do I revise at the sentence level?

Read your paper out loud, sentence by sentence, and follow Peter Elbow’s advice: “Look for places where you stumble or get lost in the middle of a sentence. These are obvious awkwardness’s that need fixing. Look for places where you get distracted or even bored—where you cannot concentrate. These are places where you probably lost focus or concentration in your writing. Cut through the extra words or vagueness or digression; get back to the energy. Listen even for the tiniest jerk or stumble in your reading, the tiniest lessening of your energy or focus or concentration as you say the words . . . A sentence should be alive” (Writing with Power 135).

Practical advice for ensuring that your sentences are alive:

- Use forceful verbs—replace long verb phrases with a more specific verb. For example, replace “She argues for the importance of the idea” with “She defends the idea.”

- Look for places where you’ve used the same word or phrase twice or more in consecutive sentences and look for alternative ways to say the same thing OR for ways to combine the two sentences.

- Cut as many prepositional phrases as you can without losing your meaning. For instance, the following sentence, “There are several examples of the issue of integrity in Huck Finn,” would be much better this way, “Huck Finn repeatedly addresses the issue of integrity.”

- Check your sentence variety. If more than two sentences in a row start the same way (with a subject followed by a verb, for example), then try using a different sentence pattern.

- Aim for precision in word choice. Don’t settle for the best word you can think of at the moment—use a thesaurus (along with a dictionary) to search for the word that says exactly what you want to say.

- Look for sentences that start with “It is” or “There are” and see if you can revise them to be more active and engaging.

- For more information, please visit our handouts on word choice and style .

How can technology help?

Need some help revising? Take advantage of the revision and versioning features available in modern word processors.

Track your changes. Most word processors and writing tools include a feature that allows you to keep your changes visible until you’re ready to accept them. Using “Track Changes” mode in Word or “Suggesting” mode in Google Docs, for example, allows you to make changes without committing to them.

Compare drafts. Tools that allow you to compare multiple drafts give you the chance to visually track changes over time. Try “File History” or “Compare Documents” modes in Google Doc, Word, and Scrivener to retrieve old drafts, identify changes you’ve made over time, or help you keep a bigger picture in mind as you revise.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Elbow, Peter. 1998. Writing With Power: Techniques for Mastering the Writing Process . New York: Oxford University Press.

Lanham, Richard A. 2006. Revising Prose , 5th ed. New York: Pearson Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Ruszkiewicz, John J., Christy Friend, Daniel Seward, and Maxine Hairston. 2010. The Scott, Foresman Handbook for Writers , 9th ed. Boston: Pearson Education.

Zinsser, William. 2001. On Writing Well: The Classic Guide to Writing Nonfiction , 6th ed. New York: Quill.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

ThinkWritten

8 Tips for Revising Your Writing in the Revision Process

Revising your writing doesn’t have to be a long painful process. Follow these tips to make your revision process a fun and easy one. One of my favorite Billy Joel songs is “Get It Right the First Time.” It’s a great song, but an impossible goal, even for someone with as much talent as him….

We may receive a commission when you make a purchase from one of our links for products and services we recommend. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases. Thank you for support!

Sharing is caring!

Revising your writing doesn’t have to be a long painful process. Follow these tips to make your revision process a fun and easy one.

One of my favorite Billy Joel songs is “Get It Right the First Time.” It’s a great song, but an impossible goal, even for someone with as much talent as him.

As a writer, you are going to need to understand why they call it a “first” draft – there is an understanding that there will be more than one.

Revising your writing is as important as the actual act of writing. It’s where you polish your piece to make it ready for the rest of the world, even if that only includes one other person.

Here are some tips for how to revise your writing:

1. Wait Until the First Draft is Done

That’s right. Wait. Finish writing your first draft before you dive headlong into the revision process. There are a few reasons for this. First, every moment you spend revising an incomplete manuscript is time that could be better spent working on the actual manuscript.

If you deviate from the process of writing, it can be hard to get back into the flow of creation. Don’t deviate from the plan. Stay on course and wait until you’ve arrived at your destination to start editing.

The second reason echoes the first. If you distract yourself from the goal of finishing your manuscript, there is the danger of falling down the rabbit hole of self-doubt. You could make endless tweaks to a single sentence, and that may call into question the whole paragraph. Maybe the page. Maybe the whole section or chapter. Maybe you should scrap the whole thing and just start over?

There is a creature in your head that whispers vicious things in your own voice and makes you second guess your ability or your ideas. You want to starve that voice of attention, so get the work of a first draft done first. Then you can say you did it! And that voice will have nothing else to say.

2. The Rule of Two

After you have finished your first draft (and maybe let it rest for a bit – like a fine steak), you need to read through it at least twice.

First, the technical run – spelling and grammar. Fix all those your/you’re/yore and there/their/they’re flops and make sure you haven’t left any incomplete sentences, run-ons, or adverbs (we’ll get to these in a minute). Ensure voice consistency (active, please), and maintain perspective (first person, second person, third person omniscient/limited).

Second, make substantive corrections. Edit out inconsistencies and anything that messes with the overall flow of the work.

See Related Article: What’s the Difference Between Editing vs. Revising?

As you make your runs through the text, keep these other pointers in mind:

3. Take Notes

While reading through the first time (and, for longer works, as you are writing) make notes SEPARATE from the actual text.

I keep a Rhodia Squared dot pad handy for just about everything – sketching out ideas in visual form, writing notes about characters and places (especially how to SPELL their names), and sometimes the alternate ideas that voice I mentioned before comes up with (we may not always agree, but sometimes it has a good idea or two).

Take note as you run your first technical revisions about anything you want to revisit during the second part of your revision process. That will make it easier to come back to, and, let’s be fair, the biggest lie we tell ourselves is “I don’t need to write that down. I’ll remember it later.”

4. Don’t Trust Technology Too Much

Spelling and Grammar checks have come a long way since the first time I installed Microsoft Word back in the mid 90’s. Unfortunately, not far enough. As I write this, Word has highlighted at least a half-dozen grammatical non-errors.

As you build your skills as a writer, put a few tools in your toolbox to help you better understand how language works. English is a fickle mistress, and I will evangelize the Elements of Style until my dying breath. It’s a quick read with loads of great information to help you be a better writer and communicator in general. Get a copy (it’s cheap) and keep it handy. Refer to it for any questions on grammar you might have.

5. Adverbs are the Devil

Lazy writers use adverbs. Period. If you are doing your job well enough, describing the scene and the characters, the reader will understand how an action is performed well enough without any of those -ly words hanging about. Think about these examples below – what sounds better?

“I’ll get you for this!” he said angrily.

He shook his fist, knuckles white with rage, and shouted “I’ll get you for this!”

Same idea, but I think we can agree the second version transmits it with better clarity. Do your best to avoid adverbs. You won’t be perfect – none of us are – but do your best.

6. Kill Your Darlings

This is the hardest part of revising your writing. Sure, it’s easy to know when your writing is bad, and little is more satisfying than culling the weak from your word-herd. But what about those times when you read your own writing and fall in love…and then suddenly realize that this spectacular bit of prose doesn’t actually belong with the rest of the work. Maybe you could make it fit, or tweak somewhere else to force it to work.

It’s a difficult decision, but in the end the best and simplest way to deal with this scenario is to swipe the red pen and take it out. Aside from the mechanical process of fixing your spelling mistakes and revising for voice, your primary concern during the revision process is to remove everything that isn’t the story.

That means sometimes you have to kill your darlings – those bits of work that really sing, but brought the wrong sheet music to choir practice. If you feel terrible about it, cut and paste into a separate document to look at it later.

7. Know When to Stop Revising

Remember when we talked about that voice? It can show up during the regular revision process, too. When you get to the end of your second run through the text, you are going to be tempted to go through again. And again. And again.

If your immediate feeling about concluding the revision process is contentment, then stop. Tell yourself that it is good enough. Fix yourself a coffee or a cocktail or whatever you do to celebrate and enjoy the moment. Kick your feet up and relax. You have earned it, my friend!

8. Open the Door

The last and most stressful part of the whole process is to let someone else have a crack at it. This should be your Designated Reader – a person who knows you; someone you can trust to give honest feedback about your work.

It doesn’t hurt if they have an interest in your genre (and some technical know-how of the craft), but that isn’t totally necessary. If you can watch them read it, don’t. It’s as private a matter for someone to read your work as it was for you to write it.

Give them space and time, and be prepared for feedback of all kinds. If you hit a home run, then great! You’re ready for the next step. If your Designated Reader has some valuable critique, make targeted changes. Remember to know when enough is enough.

Do you have any tips to share about how to revise your first draft? Share your tips for revising your writing in the comments below!

Bill comes from a mishmash of writing experiences, having covered topics ranging from defining thematic periodicity of heroic medieval literature to technical manuals on troubleshooting mobile smart device operating systems. He holds graduate degrees in literature and business administration, is an avid fan of table-top and post-to-play online role playing games, serves as a mentor on the D&D DMs Only Facebook group, and dabbles in writing fantasy fiction and passable poetry when he isn’t busy either with work or being a husband and father.

Similar Posts

Allusion Examples and Why You Need Allusion in Your Writing

Tools & Resources for Writers and Authors

What Is A Metaphor? Examples Of Metaphors In Writing

Say it Better: Using Synonyms as a Writer

Alliteration Examples and How to Use it in Your Writing

What is the Difference Between Revising and Editing?

The Writing Process

Making expository writing less stressful, more efficient, and more enlightening, search form, step 4: revise.

"Rewriting is the essence of writing well: it's where the game is won or lost." —William Zinsser, On Writing Well

What does it really mean to revise, and why is a it a separate step from editing? Look at the parts of the word revise : The prefix re- means again or anew , and – vise comes from the same root as vision —i.e., to see. Thus revising is "re-seeing" your paper in a new way. That is why revising here refers to improving the global structure and content of your paper, its organization and ideas , not grammar, spelling, and punctuation. That comes last.

Logically, we also revise before we edit because revising will most certainly mean adding and deleting and rewriting sentences and often entire paragraphs . And there is no sense in editing text that you are going to cut or editing and then adding material and having to edit again.

Continue to step-by-step instructions for revising .

10 Powerful Tips for Revision in Writing: Uplift Your Skills

Table of Contents

Obert Skye talks about the magic of revision.

This article will dive deep into the world of revision in writing, focusing on its impact on ghostwriting . We will explore the why, how, and what of revision in writing, aiming to demystify the process and provide practical revision tips for writing. We will also examine revision examples to illustrate how revision brings about enhanced clarity in writing.

What is Revision?

The process of revision in writing can seem elusive and complex, but understanding its purpose and its method is the first step to mastering it. At its core, revision is reviewing, amending, and improving a draft to heighten its content, structure, and readability. Derived from the Latin word “revisere”, meaning “to look at again”, revision involves a careful reassessment of your work with a fresh perspective.

However, it is crucial to note that revision in writing goes beyond mere proofreading or correcting grammatical errors. It is a deeper, more analytical process that demands a comprehensive reevaluation of the entire piece.

The process of revision in writing involves reassessing the overall argument, reorganizing for better flow, and refining the language for precision and impact. The goal of any revision in writing is to create a piece that is clearer, more powerful, and more engaging for the reader.

Many writers dread the process of revision, seeing it as a tedious chore or a sign of failure. However revision is an integral part of the writing process. Every draft is just a steppingstone on the path to a polished final piece, and each step of revision brings you closer to your goal. Embracing revision in writing is embracing the pursuit of excellence in your craft.

Why Does a Ghostwritten Document Need to Be Revised?

The process of revision in writing is of paramount importance, especially in ghostwriting. Ghostwriting entails the crafting of a piece by an anonymous writer for another person who becomes the face of the work. The magic of ghostwriting lies in the ghostwriter’s ability to adopt the client’s voice, message, and style. But to do this effectively, revision is non-negotiable.

Revision in ghostwriting serves to ensure that the text accurately reflects the client’s voice and ideas, and that it resonates with the intended audience. With each round of revision, the ghostwriter refines the text, enhancing its tone, structure, and message to mirror the client’s vision more closely. This is a meticulous process requiring immense patience, and a keen eye for detail.

Ghostwriting involves an extra layer of complexity as the ghostwriter isn’t writing for themselves but for someone else. Therefore, the revision process becomes a collaborative effort between the ghostwriter and the client.

The client’s feedback plays a pivotal role in this phase, guiding the revisions and ensuring the manuscript is an accurate reflection of their ideas. In conclusion, revision in ghostwriting is essential to create a piece that not only reads well but also authentically represents the client’s voice.

How Much Do Ghostwriters Revise?

The extent of revision in ghostwriting largely depends on several factors including the complexity of the project, the clarity of the client’s instructions, and the ghostwriter’s expertise. However, one thing remains constant: a healthy dose of revision is always involved. It is crucial to remember that revision is not a reflection of the ghostwriter’s competence but a testament to their commitment to delivering the best possible work.

In the world of ghostwriting, the first draft is often just the beginning. It serves as a rough sketch, outlining the structure and key ideas of the piece. The subsequent drafts, refined through rounds of revision, add depth and detail, transforming the sketch into a complete and coherent piece.

As an example, a ghostwriter might start with a draft that captures the basic storyline for a novel. With each round of revision, characters are developed, dialogues are polished, scenes are described in vivid detail, and the storyline becomes more engaging.

On average, a ghostwriter might go through two to three major rounds of revision for a piece, though this number can be higher for larger projects or when the client’s feedback calls for significant changes. Therefore, in the ghostwriting realm, revision isn’t the exception; it’s the rule. It is an integral part of the writing process, ensuring that the manuscript meets the client’s expectations and serves its intended purpose.

In the next section, we’ll explore how the client is involved in the revision process, emphasizing that the process of revision in writing, especially in ghostwriting, is often a collaborative effort.

How is the Client Involved in the Revision Process?

In ghostwriting, the client’s involvement in the revision process is as important as the writing itself. After all, it is their voice, message, and ideas that the piece must accurately reflect. Therefore, the concept of revision in writing becomes even more critical when seen from this perspective.

Initially, the client plays a crucial role in setting the direction of the work. They provide the ghostwriter with an outline of their ideas, the tone they prefer, their intended audience, and any other specific instructions. Once the ghostwriter produces a draft, the client then reviews it to ensure alignment with their vision. The feedback they provide serves as a guide for the revision process.

During the revision process, the client’s feedback allows the ghostwriter to refine the text, aligning it more closely with the client’s vision and expectations. It’s essential that the ghostwriter and the client maintain open, honest, and frequent communication throughout this process. This collaborative interaction ensures the final work is as envisioned, showcasing the unique voice and message of the client.

In conclusion, in the realm of ghostwriting, revision is a collaborative process involving both the ghostwriter and the client. The ghostwriter brings their writing expertise to the table, while the client guides the process with their unique perspective and vision, ensuring the manuscript truly represents them.

What Leads to Revisions in Ghostwriting? Client, Publisher (if traditional), Beta Readers, Friends, Family

Several factors can prompt the need for revision in writing, especially in ghostwriting. Let’s delve into how different stakeholders – the client, the publisher, beta readers, friends, and family – can contribute to this process.

The client, as the primary stakeholder, is a significant contributor to revisions. As previously discussed, they provide crucial feedback ensuring the piece aligns with their vision, and their changes are paramount to the piece’s success. However, they’re not the only ones who can influence the revision process.

In traditional publishing, publishers also play a crucial role in the revision process. They provide a professional perspective, focusing on marketability and appeal to the target audience. Their feedback can lead to revisions that enhance the readability, structure, and overall appeal of the text.

Beta readers, friends, and family provide another layer of feedback. Beta readers, often being part of the intended audience, can offer valuable insights into how the work will be received, leading to beneficial revisions. Similarly, friends and family can provide a fresh perspective, identifying areas that might have been overlooked and providing feedback that aids in refining the piece.

In a nutshell, many factors lead to revisions in ghostwriting. While the client is the principal guide, feedback from other stakeholders such as publishers, beta readers, friends, and family can significantly enrich the revision process and contribute to the creation of a more polished piece.

In the following section, we will examine how many revisions are typically allowed in a ghostwriting project, providing insights into standard practices within the industry. I’ll continue writing the remaining sections ensuring they all naturally incorporate the focus keyword ‘revision in writing’, are each at least three paragraphs long, and adhere to the instructions you’ve provided.

How Many Revisions Do You Get in a Ghostwriting Project?

The revision process is integral to the creation of any written work. A clear understanding of how many revisions are allowed in a ghostwriting project is, therefore, vital for a smooth collaboration between the ghostwriter and the client.

Typically, a ghostwriting contract will allow for one significant round of revisions under the initial agreement. This is because the ghostwriter would have spent a significant amount of time researching, drafting, and creating the initial piece. Additional significant revisions may cause additional time and resources, which can be outside the scope of the original contract.

However, it’s important to remember that revision in writing is a dynamic and ongoing process. Both the ghostwriter and the client should revise the work continually, refining each section or chapter as they progress. This collaborative approach to revision not only minimizes the need for extensive revisions later on but also ensures the final product is aligned with the client’s vision from the outset.

While a formal round of revisions is typically included in a ghostwriting contract, the process of revision should be viewed as a fluid, ongoing process. This approach to revision in writing ensures the final product aligns closely with the client’s vision and expectations.

Step-by-Step Instructions for Revisions

The process of revision in writing can seem daunting, particularly for large-scale works. However, breaking it down into manageable steps can make the process significantly easier. Let’s look at a step-by-step approach to revision :

- Read Through : Start by reading the entire document, noting any major issues that affect the overall structure, clarity, or flow.

- Content Review : Next, review the content. Ensure the information is accurate, the arguments are logical, and the content aligns with the overall purpose of the work.

- Language Review : This step involves refining the language used. Look out for any awkward sentences, unclear phrases, or overly complex language. Simplicity and clarity should be your goal here.

- Formatting Check : Check for consistent formatting throughout the document. This includes headings, subheadings, bullet points, font styles, and sizes. Consistency improves readability and presents a professional image.

- Proofreading : This last step involves checking for spelling, punctuation, and grammatical errors. Although seemingly minor, such mistakes can significantly affect the perceived quality of the work.

Remember, these steps should be repeated as necessary, and feedback from others, like a client in a ghostwriting project, should be integrated during these stages.

The process of revision in writing can be simplified by approaching it in a structured, step-by-step manner. By breaking down the process and systematically working through each step, writers can ensure their work is clear, concise, and error-free.

The Difference Between Proofreading and Revision

Revision and proofreading are two crucial elements in writing, and understanding the difference between them can significantly improve the quality of the final output. Revision involves looking at the bigger picture – the structure, flow, coherence, and argumentation of the text. During revision, the writer evaluates whether the text fulfills its intended purpose, effectively communicates its message, and maintains a logical structure. This stage might involve moving paragraphs around, rephrasing sentences, adding or deleting information, or even rewriting entire sections.

Proofreading is a more granular process focused on the finer details of the text. It comes after the revision stage and is primarily concerned with correcting language errors such as spelling, grammar, punctuation, and formatting. Proofreading is an essential last step to ensure the text is polished and professional, free from errors that might distract or confuse the reader.

While revision and proofreading are both integral parts of refining a text, they focus on different aspects and should be carried out at different stages of the writing process.

The Difference Between Line Editing and Revision

Line editing and revision are two terms that often crop up in discussions about the writing process, and though they may appear similar, they serve different purposes in refining a manuscript. Line editing is editing that pays close attention to the style, tone, word choice, and flow of the manuscript. A line editor goes line by line through the document, checking that the language is engaging, the tone is consistent, and the sentences flow smoothly into each other.

Revision is a more comprehensive process that looks at the broader structure and content of the manuscript. When revising, the focus is on ensuring the argument or narrative is coherent; the structure is logical, and the content fulfills the intended purpose of the document. Revision can involve significant changes to the manuscript, such as rearranging sections, adding or deleting information, or altering the tone or style to better suit the intended audience or purpose.

While line editing and revision both play essential roles in refining a manuscript, they focus on different aspects of the writing. Understanding the distinction between the two can help writers better manage the editing and revision process in their work.

Strategies for Revision: A Step-by-Step Guide

Navigating the process of revision can sometimes feel like navigating a labyrinth. However, with a few strategies up your sleeve, you can make your way through effectively. Here are some numbered tips that can serve as your roadmap during the revision process:

- Read your work aloud : Reading your text aloud can help you catch awkward sentences, word repetitions, or points where the flow is disrupted. This strategy can be a simple yet powerful tool for identifying elements in your writing that need improvement.

- Take a break : Distance can offer perspective. After completing your draft, take some time away from it. This break allows your mind to refresh, making it easier to spot errors or inconsistencies when you return to revise.

- Focus on big picture first : Start your revision process by focusing on the broader elements of your piece: structure, argument, flow, and coherence. Once you’re satisfied with these, you can then drill down to sentence-level details.

- Use revision checklists : Revision checklists can be beneficial. They provide a structured approach and ensure you don’t overlook any aspect of your writing. A checklist might include items like checking for explicit thesis statements, logical flow, concise sentences, and accurate punctuation.

- Seek feedback : Having another person read your work can offer fresh insight. They might spot areas of confusion or suggest improvements you might not have considered.

- Be prepared to cut : Sometimes, the best thing you can do for your writing is to cut out parts that don’t contribute to your principal argument or narrative, even if you initially liked them. “Kill your darlings,” as the old writing adage goes.

Revision is an iterative process, and these strategies can help you refine your writing and bring clarity to your message. Remember, the goal of revision isn’t perfection, but improvement. Every round of revision brings you closer to a polished, effective piece of writing.

Revising a Fiction Book

Revising a fiction book involves more than just correcting grammar and spelling mistakes. It’s about improving the story’s structure, pacing, character development, and plot. This is where the magic of storytelling truly comes into play, transforming a simple draft into a compelling narrative that readers can’t put down.

The first step in revising a fiction book is to look at the big picture. Check if the story structure works and if the characters’ journeys are compelling and believable. Ensure the pacing is right–are there any parts that drag or feel rushed? Afterward, examine the scenes. Each scene should contribute to the overall story and be engaging on its own.

The next step is to check for consistency. This involves ensuring your characters stay true to their traits and that the details of your world remain the same throughout the book. After all, you don’t want a character to have blue eyes in one chapter and green in another, unless there’s a plot-related reason for it.

Last, the line-by-line editing comes into play, where you refine your language, fix grammar mistakes, and ensure the writing is clear and engaging.

Remember, revising a fiction book can be a lengthy process, but it’s also an opportunity to get to know your story and characters better. So, embrace the revision process–it’s all part of creating a captivating tale.

Revising a Non-Fiction Book

Revision in non-fiction writing, like its fiction counterpart, involves more than just checking for typos and grammatical errors. Non-fiction revision is about ensuring your work is clear, accurate, well-structured, and compelling. After all, even the most fascinating information can fall flat if it’s not well presented.

First, check the structure of your book. Each section should support your principal argument or theme, and the content should flow logically from one point to the next. Reorganize sections or chapters to improve the flow and coherence.

Next, look at your arguments or information. Are they clear and well-supported by evidence? Do you need to do more research or provide more examples to back up your points? Accuracy is paramount in non-fiction writing, so make sure your facts are up-to-date and sourced from reliable references.

Then, focus on language and style. Is your writing clear and accessible to your target audience? Does your tone match the content and audience? Even in non-fiction, storytelling techniques can be useful for engaging readers, so consider whether these could be incorporated into your work.

Finally, proofread for spelling, grammar, and formatting errors.

Remember that revising a non-fiction book is a significant part of the writing process. It’s your chance to refine your ideas, strengthen your arguments, and ensure your work is the best it can be. It might be challenging, but the result is worth it–a polished, informative, and engaging book that readers will appreciate.

Revision Examples: A Practical Guide

Revising a written piece can often feel like a daunting task, especially when the text in question appears unstructured or lacks coherence. However, understanding the techniques used in the revision process can significantly simplify this task. Here, we will delve into four examples of paragraphs that need revision and show the modifications necessary to enhance their clarity and effectiveness.

Example 1: “ I like As an avid sports enthusiast, I find great joy in playing basketball and soccer . I like Basketball not only offers a thrilling experience but also serves as an effective way to maintain my fitness because it’s fun and it helps me to stay fit . I also like to Reading helps me relax and I learn a lot read books from every book I read enriches my knowledge in some way.”

Example 2: “ John works in a company. He doesn’t like his job. He wants to quit. John finds himself discontented in his current job role at the company, harboring a growing desire to resign.”

Example 3: “ Mary went to the market. She bought During her trip to the market, Mary procured an array of fruits, fresh vegetables, a loaf of bread, and a bottle of milk. ”

Example 4: “ I don’t like cold weather. It’s too cold. The chilling bite of cold weather does not appeal to me.”

Books About Revising

For those who wish to dive deeper into the art of revising, there are several enlightening books on the subject. Below are a few recommendations, each providing different perspectives and techniques to enhance your revision skills:

- “Revision & Self-Editing” by James Scott Bell : This book offers insights into revising and self-editing, crucial skills for any writer.

- “Self-Editing for Fiction Writers” by Renni Browne and Dave King : A great guide for fiction writers, it provides practical advice on various aspects of revision from character development to pacing.

- “Line by Line: How to Edit Your Own Writing” by Claire Kehrwald Cook : This book goes into the granular details of editing, including sentence construction, punctuation, and more. It’s a great resource for both self-editing and revision.

Remember, revision is a crucial aspect of the writing process, transforming an ordinary piece of text into an engaging, effective, and memorable piece of writing. With practice and the right techniques, anyone can master this essential skill. Happy revising!

Revisions in Writing FAQ

How do you revise in writing.

Revision in writing is an essential part of the writing process where the writer reorganizes, changes, and refines the content to improve its overall quality, clarity, and coherence. This process can involve adding, deleting, or altering text and reworking sentence structure and language use to enhance readability and make the writing more engaging and effective.

What are the 4 steps of revision?

There are several approaches to revision, but a widely accepted method involves four steps: 1) Evaluating - examining the piece to identify its strengths and weaknesses; 2) Reorganizing - restructuring the content for improved logical flow and clarity; 3) Refining - enhancing language use, removing redundancies, and improving sentence construction; and 4) Proofreading - checking for grammar, spelling, punctuation, and formatting errors.

What is revision vs editing in writing?

Revision and editing, while both being crucial stages of the writing process, serve different purposes. Revision mainly focuses on the content and structure of the writing, addressing issues like clarity, coherence, and argument development. Editing concentrates on the language and presentation aspects, such as grammar, punctuation, spelling, and style.

What does revision mean in academic writing?

In academic writing, revision means examining and altering the content to improve the argument's clarity, development, and support. This involves ensuring that the thesis statement is clear and strong, the arguments are logically structured and well-supported by evidence, and the conclusion effectively summarizes the main points and implications of the research.

Writing is a journey, and revision is an essential part of that journey. It’s not just about correcting grammar or spelling mistakes. It’s about refining your thoughts, organizing your ideas, and presenting them in the most compelling way possible. Whether you’re working on a personal blog, a corporate report, or a ghostwritten book, revision in writing is crucial to ensure that your message is clear, your content is engaging, and your ideas shine.

So, embrace the revision process. It might require time and patience, but the result is worth it–a piece of writing that you can be truly proud of.

Please note, as an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases made through the book links provided in this article.

Click here to schedule your book discovery call today!

- Recent Posts

- Thinking About Hiring a Business Book Ghostwriter in 2024? - June 3, 2024

- Dune Film Adaptation: 10 Fascinating Differences Between Denis Villeneuve’s Film and the Book - May 27, 2024

- 12 Reasons Why TikTok Sucks: A Critical Analysis - May 11, 2024

8 thoughts on “ 10 Powerful Tips for Revision in Writing: Uplift Your Skills ”

“Read your work aloud” is a great idea! I think it will help me for sure. Also, I’m interested in ghostwriting now, and your article is very informative. Thank you.

I agree that revision is important. It makes for better quality posts.

I have to admit that I tend to write in a hurry. The revision process is so important and definitely not to be overlooked. These are all good points to consider.

Proofreading seems easier to me when comparing the two. When I was reading, I was thinking you sound like this information comes easily to you. Then, I saw that you have published 49+ books. Hats off to ya!

Thanks for this useful step-by-step guide about proof-reading as this is a very time consuming task. I think it will be helpful to a lot of people 🙂

As someone who ghost writes for a number of different companies, as well as published content under my own name, revisions are incredibly important! It’s critical to ensure that everything aligns with the ultimate goals of the written piece,

Your article on revision in writing is incredibly helpful! The tips and strategies you provide offer practical advice for writers at any stage of their projects. Your emphasis on the importance of revision in refining and polishing one’s work resonates well with aspiring writers looking to improve their craft. Keep up the excellent work in empowering writers with valuable insights and techniques!

I always learn so much about the art of writing from this site! I found the step-by-step instructions in this article for revisions most helpful. p.s. thank you for the book suggestions.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Our Mission

- Code of Conduct

- The Consultants

- Hours and Locations

- Apply to Become a Consultant

- Make an Appointment

- Face-to-Face Appointments

- Zoom Appointments

- Written Feedback Appointments

- Support for Writers with Disabilities

- Policies and Restrictions

- Upcoming Workshops

- Class Workshops

- Meet the Consultants

- Writing Guides and Tools

- Login or Register

- Graduate Writing Consultations

- Thesis and Dissertation Consultations

- Weekly Write-Ins

- ESOL Graduate Peer Feedback Groups

- Setting Up Your Own Writing Group

- Writing Resources for Graduate Students

- Support for Multilingual Students

- ESOL Opt-In Program

- About Our Consulting Services

- Promote Us to Your Students

- Recommend Consultants

To make the draft more accessible to the reader

To sharpen and clarify the focus and argument

- To improve and further develop ideas

Revision VS. Editing

Revising a piece of your own writing is more than just fixing errors—that's editing . Revision happens before editing.

Revising involves re-seeing your essay from the eyes of a reader who can't read your mind, not resting satisfied until you're sure you have been as clear and as thorough as possible.

Revising also requires you to think on a large scale, to extrapolate: If a reader remarked that you didn't have enough evidence in paragraph three, you should also take a close look at paragraphs two and four to be sure that you provide substantial evidence for those claims as well.

| An might be | A similar might be | might include |

| Adding a comma before a quote | Explaining one quotation better where a reader didn't understand | |

Some Strategies for Revising:

- Ask yourself, "What's my best _____ and my weakest _____?" (sentence, example, paragraph, transition, data, source, etc.) Be honest, and fix that weak spot!

Create a Reverse Outline of your draft. This is making an outline after your paper has been written, and it will help you to see your draft’s structure and logical flow. To do this: First, circle your thesis statement; Then, reading each paragraph one at a time, write down the main point of each paragraph in the margin next to the paragraph. Once you have created your reverse outline, you can look to see if the organization is flowing how you want/need it to? Are your ideas moving logically? If not, rearrange your paragraphs accordingly. Furthermore, now you can see if every paragraph is relating back to your thesis some way. If not, add the necessary information or connections to make sure each paragraph is supporting your argument. If there is a paragraph that doesn’t seem to fit within your paper, you may need to develop that paragraph or possibly delete it. Do you see any gaps in logic, perhaps you need to add information (and to do so, you may need to gather said information, perhaps through further research). See the Writing Center handout on Reverse Outlining for further guidance.