How Housing Costs Drive Levels of Homelessness

Data from metro areas highlights strong connection.

Navigate to:

- Table of Contents

A new analysis of rent prices and homelessness in American cities demonstrates the strong connection between the two: homelessness is high in urban areas where rents are high, and homelessness rises when rents rise.

To identify and illustrate the housing market dynamics driving these trends, The Pew Charitable Trusts compared homelessness and rent data in 2017 and 2022. In recent years, many metro areas in the U.S. have seen stark increases in levels of homelessness along with fast-rising rents. At the same time, some other locales that saw slow rent growth experienced declines in homelessness.

Media reports have highlighted increases in homelessness and the emergence of encampments in numerous cities, including Austin , Texas; Fresno , California; Phoenix , Arizona; Raleigh , North Carolina; Sacramento , California; and Tucson , Arizona. But other urban areas where homelessness declined over the same period—such as in Chicago, Houston, Minneapolis, and Philadelphia—recorded slower growth in rents than in the U.S. overall.

A large body of academic research has consistently found that homelessness in an area is driven by housing costs , whether expressed in terms of rents , rent-to-income ratios , price-to-income ratios , or home prices. Further, changes in rents precipitate changes in rates of homelessness : homelessness increases when rents rise by amounts that low-income households cannot afford . Similarly, interventions to address housing costs by providing housing directly or through subsidies have been effective in reducing homelessness . That makes sense if housing costs are the main driver of homelessness, but not if other reasons are to blame. Studies show that other factors have a much smaller impact on homelessness .

Much of the research looks at the variation in homelessness among geographies and finds that housing costs explain far more of the difference in rates of homelessness than variables such as substance use disorder, mental health, weather, the strength of the social safety net, poverty, or economic conditions. Some vulnerabilities strongly influence which people are susceptible to homelessness, but research has repeatedly concluded that these factors play only a minor role in driving rates of homelessness compared with the role of housing costs.

For its analysis, Pew reviewed the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s homelessness data from 2017 and 2022 and Apartment List rent data covering the same period. In the six metro areas highlighted where homelessness rose sharply, rents increased faster than the national average. (See Figure 1). Over the same period, the four urban areas featured that experienced declines in homelessness saw low rent growth.

In some areas, the relationship between housing costs and rates of homelessness is less clear, perhaps because of data volatility or the role played by other factors that influence homelessness. But the strength and consistency of researchers’ findings over time indicate that these places are the exception and that the weak relationship may be temporary.

Recent Pew research indicates that cities that added to their housing supply in recent years , typically by reforming their local zoning codes to allow more apartments to be built, succeeded in keeping rent growth low . On the other hand, several areas in which homelessness spiked had added little to their local housing supply. For example, the Fresno and Tucson areas added just 2.7% and 3.2%, respectively, to their housing stock between 2017 and 2021, despite high demand for homes. The Austin area, meanwhile, added 15.8% to its housing stock despite its restrictive zoning code , but that still fell short of its 22.7% growth in households over that time. With so many households seeking too few homes, rents climbed.

Throughout the United States, rents have reached all-time highs . Half of renters nationwide now spend at least 30% of their income on rent, and a quarter spend at least 50%. As recently as the 1970s, when rents as a share of income were far lower, homelessness was rare in the United States and housing was often available in buildings where individuals would rent private rooms but share kitchens, bathrooms, or common spaces. These low-cost units helped stave off homelessness because someone earning low wages or receiving disability benefits could usually afford to rent a private room . In the decades since, zoning or building code restrictions in most cities prevented more of these units from being developed , and city governments encouraged their conversion into other uses.

There are still places in the U.S. where levels of homelessness are low, either because those places have low-cost housing readily available—such as Mississippi , where homelessness is 10 times lower than California—or because they have rapidly added housing and made a concerted effort to reduce the ranks of residents without homes. In Houston, the rate of homelessness is 19 times lower than it is in San Francisco, even though Houston’s population has grown more than San Francisco’s in the past decade. (See Figure 2.)

Looking at these markets helps to show how population growth generally does not explain growth in homelessness, except in instances where there is not a sufficient increase in the housing supply. Examples of that include Vermont and Maine , both of which until recently have had very restrictive zoning that limited building more homes. Each saw an influx of residents during the COVID-19 pandemic, and homelessness increased 151% and 110% in those states , respectively, from 2020 to 2022.

The metro areas shown in Figure 1 illustrate how research has found that increases in rents cause increases in homelessness. Those shown in Figure 2 exemplify the related, but distinct, finding from academic research that areas with high rents have high rates of homelessness.

The academic research has consistently found that allowing more homes to be built keeps housing costs down. In tandem with the work showing that housing costs are the primary driver of homelessness, the findings suggest that allowing more housing to be built, whether subsidized or not, can reduce homelessness. What distinguishes places in the U.S. with low levels of homelessness is that housing is more abundant relative to the demand and, therefore, costs less. Recognition of the critical need to make sufficient housing available to those going through or at risk of homelessness—rather than requiring participation in programs focused on vulnerabilities such as substance use or mental health issues—has been bipartisan. Philip Mangano and Barbara Poppe, the leaders of the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness under Presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama, respectively, both reviewed the analysis in this article and have championed this approach.

Homelessness and housing affordability have become high priorities for Americans , according to surveys. The evidence shows that allowing more lower-cost housing, such as apartments or individual rooms with shared facilities, can help solve both problems. As stakeholders work to address these difficult issues, welcoming more housing—especially low-cost housing—will be crucial.

Alex Horowitz is a director and Chase Hatchett and Adam Staveski are senior associates with The Pew Charitable Trusts’ housing policy initiative.

Don’t miss our latest facts, findings, and survey results in The Rundown

Pathways to Homeownership: Housing in America

In this episode, Alex Horowitz and Tara Roche, directors of The Pew Charitable Trusts’ housing policy initiative, join us to discuss some of the challenges—and how to overcome them—for those pursuing homeownership.

NY Housing Shortage Pushes Up Rents and Homelessness

Housing costs have soared in much of the United States over the past decade. In 2022, the median rent-to-income ratio reached 30% for the first time, with a record-high number of Americans exceeding that threshold.

More Flexible Zoning Helps Contain Rising Rents

A national housing shortage has driven up rents, leaving a record share of Americans spending more than 30% of their income on rent and making them what is known as rent-burdened. But in four jurisdictions—Minneapolis; New Rochelle, New York; Portland, Oregon; and Tysons, Virginia—new zoning rules to allow more housing have helped curtail rent growth, saving tenants thousands of dollars annually.

Rigid Zoning Rules Are Helping to Drive Up Rents in Colorado

Like their counterparts in other states, policymakers in Colorado are reconsidering zoning policies in the midst of a national housing shortage that is driving rents up to all-time highs. In Colorado, rents increased 31% between January 2017 and January 2023. Some of the state’s cities and towns saw rents rise even faster during that time, including Castle Rock (53%), Colorado Springs (47%), Loveland (42%), and Fort Collins (37%).

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

MORE FROM PEW

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Your kid can’t name three branches of government? He’s not alone.

‘We have the most motivated people, the best athletes. How far can we take this?’

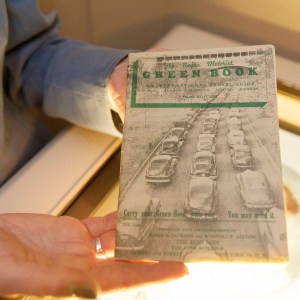

Harvard Library acquires copy of ‘Green Book’

Why it’s so hard to end homelessness in america.

City of Boston workers clear encampments in the area known as Mass and Cass.

Craig F. Walker/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Alvin Powell

Harvard Staff Writer

Experts cite complexity of problem, which is rooted in poverty, lack of affordable housing but includes medical, psychiatric, substance-use issues

It took seven years for Abigail Judge to see what success looked like for one Boston homeless woman.

The woman had been sex trafficked since she was young, was a drug user, and had been abused, neglected, or exploited in just about every relationship she’d had. If Judge was going to help her, trust had to come first. Everything else — recovery, healing, employment, rejoining society’s mainstream — might be impossible without it. That meant patience despite the daily urgency of the woman’s situation.

“It’s nonlinear. She gets better, stops, gets re-engaged with the trafficker and pulled back into the lifestyle. She does time because she was literally holding the bag of fentanyl for these guys,” said Judge, a psychology instructor at Harvard Medical School whose outreach program, Boston Human Exploitation and Sex Trafficking (HEAT), is supported by Massachusetts General Hospital and the Boston Police Department. “This is someone who’d been initially trafficked as a kid and when I met her was 23 or 24. She turned 30 last year, and now she’s housed, she’s abstinent, she’s on suboxone. And she’s super involved in her community.”

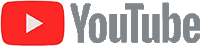

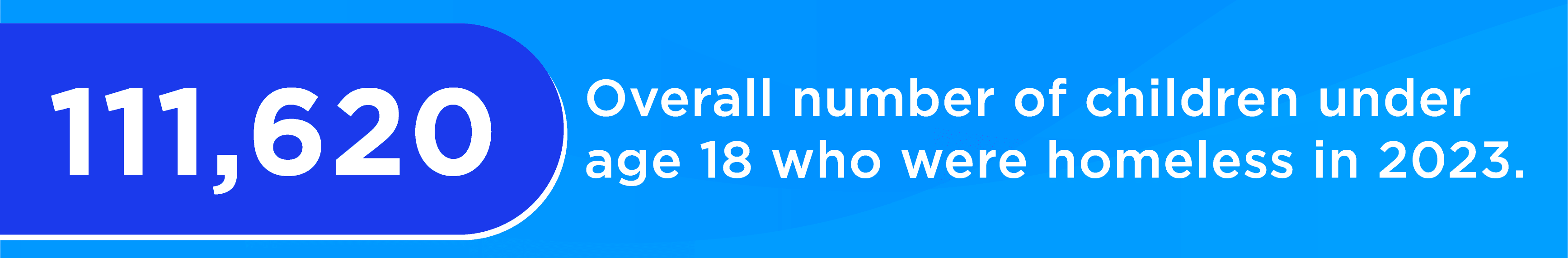

It’s a success story, but one that illustrates some of the difficulties of finding solutions to the nation’s homeless problem. And it’s not a small problem. A December 2023 report by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development said 653,104 Americans experienced homelessness, tallied on a single night in January last year. That figure was the highest since HUD began reporting on the issue to Congress in 2007 .

Abigail Judge of the Medical School (from left) and Sandra Andrade of Massachusetts General Hospital run the outreach program Boston HEAT (Human Exploitation and Sex Trafficking).

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

Scholars, healthcare workers, and homeless advocates agree that two major contributing factors are poverty and a lack of affordable housing, both stubbornly intractable societal challenges. But they add that hard-to-treat psychiatric issues and substance-use disorders also often underlie chronic homelessness. All of which explains why those who work with the unhoused refer to what they do as “the long game,” “the long walk,” or “the five-year-plan” as they seek to address the traumas underlying life on the street.

“As a society, we’re looking for a quick fix, but there’s no quick fix for this,” said Stephen Wood, a visiting fellow at Harvard Law School’s Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology and Bioethics and a nurse practitioner in the emergency room at Carney Hospital in the Dorchester neighborhood of Boston. “It takes a lot of time to fix this. There will be relapses; there’ll be problems. It requires an interdisciplinary effort for success.”

A recent study of 60,000 homeless people in Boston found the average age of death was decades earlier than the nation’s 2017 life expectancy of 78.8 years.

Illustration by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

Katherine Koh, an assistant professor of psychiatry at HMS and psychiatrist at MGH on the street team for Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program, traced the rise of homelessness in recent decades to a combination of factors, including funding cuts for community-based care, affordable housing, and social services in the 1980s as well as deinstitutionalization of mental hospitals.

“Though we have grown anesthetized to seeing people living on the street in the U.S., homelessness is not inevitable,” said Koh, who sees patients where they feel most comfortable — on the street, in church basements, public libraries. “For most of U.S. history, it has not been nearly as visible as it is now. There are a number of countries with more robust social services but similar prevalence of mental illness, for example, where homelessness rates are significantly lower. We do not have to accept current rates of homelessness as the way it has to be.”

“As a society, we’re looking for a quick fix, but there’s no quick fix for this.” Stephen Wood, visiting fellow, Petrie-Flom Center for Health Law Policy, Biotechnology and Bioethics

Success stories exist and illustrate that strong leadership, multidisciplinary collaboration, and adequate resources can significantly reduce the problem. Prevention, meanwhile, in the form of interventions focused on transition periods like military discharge, aging out of foster care, and release from prison, has the potential to vastly reduce the numbers of the newly homeless.

Recognition is also growing — at Harvard and elsewhere — that homelessness is not merely a byproduct of other issues, like drug use or high housing costs, but is itself one of the most difficult problems facing the nation’s cities. Experts say that means interventions have to be multidisciplinary yet focused on the problem; funding for research has to rise; and education of the next generation of leaders on the issue must improve.

“This is an extremely complex problem that is really the physical and most visible embodiment of a lot of the public health challenges that have been happening in this country,” said Carmel Shachar, faculty director of Harvard Law School’s Center for Health Law and Policy Innovation. “The public health infrastructure has always been the poor Cinderella, compared to the healthcare system, in terms of funding. We need increased investment in public health services, in the public health workforce, such that, for people who are unhoused, are unsheltered, who are struggling with substance use, we have a meaningful answer for them.”

“You can either be admitted to a hospital with a substance-use disorder, or you can be admitted with a psychiatric disorder, but very, very rarely will you be admitted to what’s called a dual-diagnosis bed,” said Wood, a nurse practitioner in the emergency room at Carney Hospital.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Experts say that the nation’s unhoused population not only experiences poverty and exposure to the elements, but also suffers from a lack of basic health care, and so tend to get hit earlier and harder than the general population by various ills — from the flu to opioid dependency to COVID-19.

A recent study of 60,000 homeless people in Boston recorded 7,130 deaths over the 14-year study period. The average age of death was 53.7, decades earlier than the nation’s 2017 life expectancy of 78.8 years. The leading cause of death was drug overdose, which increased 9.35 percent annually, reflecting the track of the nation’s opioid epidemic, though rising more quickly than in the general population.

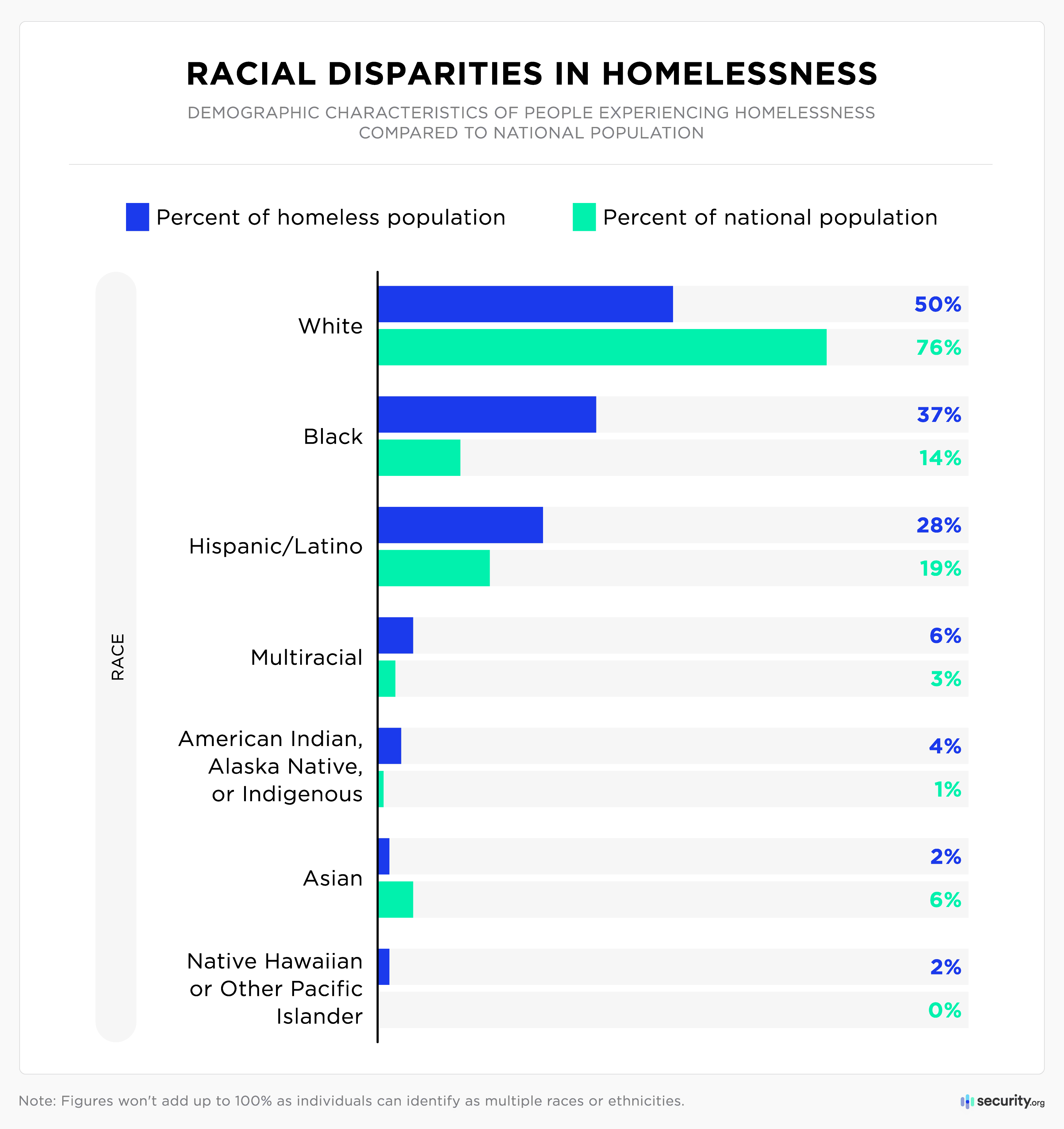

A closer look at the data shows that impacts vary depending on age, sex, race, and ethnicity. All-cause mortality was highest among white men, age 65 to 79, while suicide was a particular problem among the young. HIV infection and homicide, meanwhile, disproportionately affected Black and Latinx individuals. Together, those results highlight the importance of tailoring interventions to background and circumstances, according to Danielle Fine, instructor in medicine at HMS and MGH and an author of two analyses of the study’s data.

“The takeaway is that the mortality gap between the homeless population and the general population is widening over time,” Fine said. “And this is likely driven in part by a disproportionate number of drug-related overdose deaths in the homeless population compared to the general population.”

Inadequate supplies of housing

Though homelessness has roots in poverty and a lack of affordable housing, it also can be traced to early life issues, Koh said. The journey to the streets often starts in childhood, when neglect and abuse leave their marks, interfering with education, acquisition of work skills, and the ability to maintain healthy relationships.

“A major unaddressed pathway to homelessness, from my vantage point, is childhood trauma. It can ravage people’s lives and minds, until old age,” Koh said. “For example, some of my patients in their 70s still talk about the trauma that their parents inflicted on them. The lack of affordable housing is a key factor, though there are other drivers of homelessness we must also tackle.”

The number was the highest since the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development began reporting on the issue to Congress in 2007 .

Most advocates embrace a “housing first” approach, prioritizing it as a first step to obtaining other vital services. But they say the type of housing also matters. Temporary shelters are a key part of the response, but many of the unhoused avoid them because of fears of theft, assault, and sexual assault. Instead, long-term beds, including those designated for people struggling with substance use and mental health issues, are needed.

“You can either be admitted to a hospital with a substance-use disorder, or you can be admitted with a psychiatric disorder, but very, very rarely will you be admitted to what’s called a dual-diagnosis bed,” said Petrie-Flom’s Wood. “The data is pretty solid on this issue: If you have a substance-use disorder there’s likely some underlying, severe trauma. Yet, when we go to treat them, we address one but not the other. You’re never going to find success in the system that we currently have if you don’t recognize that dual diagnosis.”

Services offered to those in housing should avoid what Koh describes as a “one-size-fits-none” approach. Some might need monthly visits from a caseworker to ensure they’re getting the support they need, she said. But others struggle once off the streets. They need weekly — even daily — support from counselors, caseworkers, and other service providers.

“I have seen, sadly, people who get housed and move very quickly back out on the streets or, even more tragically, lose their life from an unwitnessed overdose in housing,” Koh said. “There’s a community that’s formed on the street so if you overdose, somebody can give you Narcan or call 911. If you don’t have the safety of peers around, people can die. We had a patient who literally died just a few days after being housed, from an overdose. We really cannot just house people and expect their problems to be solved. We need to continue to provide the best care we can to help people succeed once in housing.”

“We really cannot just house people and expect their problems to be solved.” Katherine Koh, Mass. General psychiatrist

Koh works on the street team for Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program.

Photo by Dylan Goodman

The nation’s failure to address the causes of homelessness has led to the rise of informal encampments from Portland, Maine, to the large cities of the West Coast. In Boston, an informal settlement of tents and tarps near the intersection of Massachusetts Avenue and Melnea Cass Boulevard was a point of controversy before it was cleared in November.

In the aftermath, more than 100 former “Mass and Cass” residents have been moved into housing, according to media reports. But experts were cautious in their assessment of the city’s plans. They gave positive marks for features such as a guaranteed place to sleep, “low threshold” shelters that don’t require sobriety, and increased outreach to connect people with services. But they also said it’s clear that unintended consequences have arisen. and the city’s homelessness problem is far from solved.

Examples abound. Judge, who leads Boston HEAT in collaboration with Sandra Andrade of MGH, said that a woman she’d been working with for two years, who had been making positive strides despite fragile health, ongoing sexual exploitation, and severe substance use disorder, disappeared after Mass and Cass was cleared.

Mike Jellison, a peer counselor who works on Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program’s street team, said dismantling the encampment dispersed people around the city and set his team scrambling to find and reconnect people who had been receiving medical care with providers. It’s also clear, he said, that Boston Police are taking a hard line to prevent new encampments from popping up in other neighborhoods, quickly clearing tents and other structures.

“We were out there Wednesday morning on our usual route in Charlesgate,” Jellison said in early December. “And there was a really young couple who had all their stuff packed. And [the police] just told them, ‘You’ve got to leave, you can’t stay here.’ She was crying, ‘Where am I going to go?’ This was a couple who works; they’re employed and work out of a tent. It was like 20 degrees out there. It was heartbreaking.”

Prevention as cure?

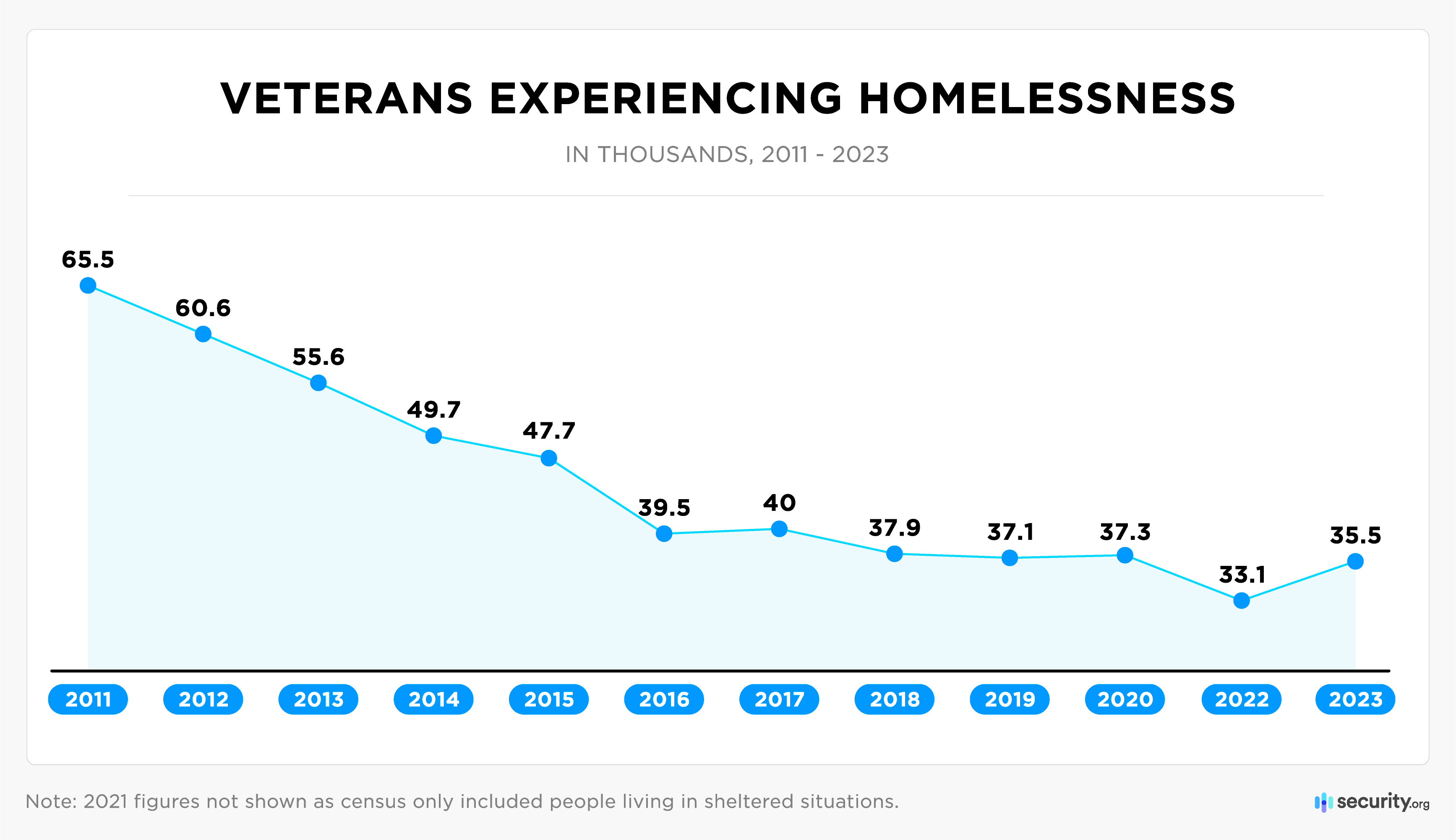

Successes in reducing homelessness in the U.S. are scarce, but not unknown. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, for example, has reduced veteran homelessness nationally by more than 50 percent since 2010.

Experts point out, however, that the agency has advantages in dealing with the problem. It is a single, nationwide, administrative entity so medical records follow patients when they move, offering continuity of care often absent for those without insurance or dealing with multiple private providers. Another advantage is that the VA’s push, begun during the Obama administration, benefited from both political will on the part of the White House and Congress and received support and resources from other federal agencies.

The city of Houston is another example. In 2011, Houston had the nation’s fifth-largest homeless population. Then-Mayor Annise Parker began a program that coordinated 100 regional nonprofits to provide needed services and boost the construction of low-cost housing in the relatively inexpensive Houston market.

Neither the VA nor Houston was able to eliminate homelessness, however.

To Koh, that highlights the importance of prevention. In 2022, she published research in which she and a team used an artificial-intelligence-driven model to identify those who could benefit from early intervention before they wound up on the streets. The researchers examined a group of U.S. service members and found that self-reported histories of depression, trauma due to a loved one’s murder, and post-traumatic stress disorder were the three strongest predictors of homelessness after discharge.

In April 2023, Koh, with co-author Benjamin Land Gorman, suggested in the Journal of the American Medical Association that using “Critical Time Intervention,” where help is focused on key transitions, such as military discharge or release from prison or the hospital, has the potential to head off homelessness.

“So much of the clinical research and policy focus is on housing those who are already homeless,” Koh said. “But even if we were to house everybody who’s homeless today, there are many more people coming down the line. We need sustainable policies that address these upstream determinants of homelessness, in order to truly solve this problem.”

The education imperative

Despite the obvious presence of people living and sleeping on city sidewalks, the topic of homelessness has been largely absent from the nation’s colleges and universities. Howard Koh, former Massachusetts commissioner of public health and former U.S. assistant secretary for Health and Human Services, is working to change that.

In 2019, Koh, who is also the Harvey V. Fineberg Professor of the Practice of Public Health Leadership, founded the Harvard T.H Chan School of Public Health’s pilot Initiative on Health and Homelessness. The program seeks to educate tomorrow’s leaders about homelessness and support research and interdisciplinary collaboration to create new knowledge on the topic. The Chan School’s course “Homelessness and Health: Lessons from Health Care, Public Health, and Research” is one of just a handful focused on homelessness offered by schools of public health nationwide.

“The topic remains an orphan,” said Koh. The national public health leader (who also happens to be Katherine’s father) traced his interest in the topic to a bitter winter while he was Massachusetts public health commissioner when 13 homeless people froze to death on Boston’s streets. “I’ve been haunted by this issue for several decades as a public health professional. We now want to motivate courageous and compassionate young leaders to step up and address the crisis, educate students, motivate researchers, and better inform policymakers about evidence-based studies. We want every student who walks through Harvard Yard and sees vulnerable people lying in Harvard Square to not accept their suffering as normal.”

Share this article

You might like.

Efforts launched to turn around plummeting student scores in U.S. history, civics, amid declining citizen engagement across nation

Six members of Team USA train at Newell Boat House for 2024 Paralympics in Paris

Rare original copy of Jim Crow-era travel guide ‘key document in Black history’

John Manning named next provost

His seven-year tenure as Law School dean noted for commitments to academic excellence, innovation, collaboration, and culture of free, open, and respectful discourse

Loving your pup may be a many splendored thing

New research suggests having connection to your dog may lower depression, anxiety

Good genes are nice, but joy is better

Harvard study, almost 80 years old, has proved that embracing community helps us live longer, and be happier

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Federal Homelessness Research Agenda

What would it take to prevent and end homelessness?

While decades of research have documented effective strategies for helping people exit homelessness (particularly Housing First and Critical Time Intervention), more research is needed to better understand how to scale housing and supportive services. And while communities are increasingly focused on homelessness prevention (including guaranteed basic income, flexible funding pools, and shelter diversion), the research remains limited .

In November 2023, USICH published From Evidence to Action — the first federal homelessness research agenda in more than a decade —to shape federal investments in homelessness research and offer a roadmap for academic researchers, philanthropy, students, and others committed to understanding what works to prevent and end the crisis of homelessness in the United States.

This agenda—which will evolve over time—was developed with significant public input from researchers, people with lived experience of homelessness, national organizations, and experts from federal agencies.

From Evidence to Action seeks to:

- Strengthen our nation’s collective base of knowledge on what works to prevent and end homelessness through rigorous qualitative and quantitative evidence

- Reinforce existing evidence to combat disinformation

- Align research priorities and prevent fragmentation at both the federal and non-federal levels

- Facilitate meaningful engagement of and collaboration with a diverse group of funders, researchers, people with lived expertise, and partners at every stage of developing and implementing federal research activities

- Promote research to address gaps in policy and practice, and facilitate the uptake of evidence by decision makers and service providers

- Catalyze governmental and non-governmental investment in homelessness research

The agenda focuses on the following topics:

Preventing Homelessness

- Universal Prevention

- Targeted Prevention

- Screening and Identifying Risk

- Cost and Scale

Ending Homelessness

- Cost

- Longitudinal Outcomes

- Housing and Services

- Specific Subpopulations

- Unsheltered Homelessness

- Lessons Learned From COVID-19 Response

Click to read From Evidence to Action: A Federal Homelessness Research Agenda .

Please email questions or comments to [email protected] .

Addressing the U.S. homelessness crisis

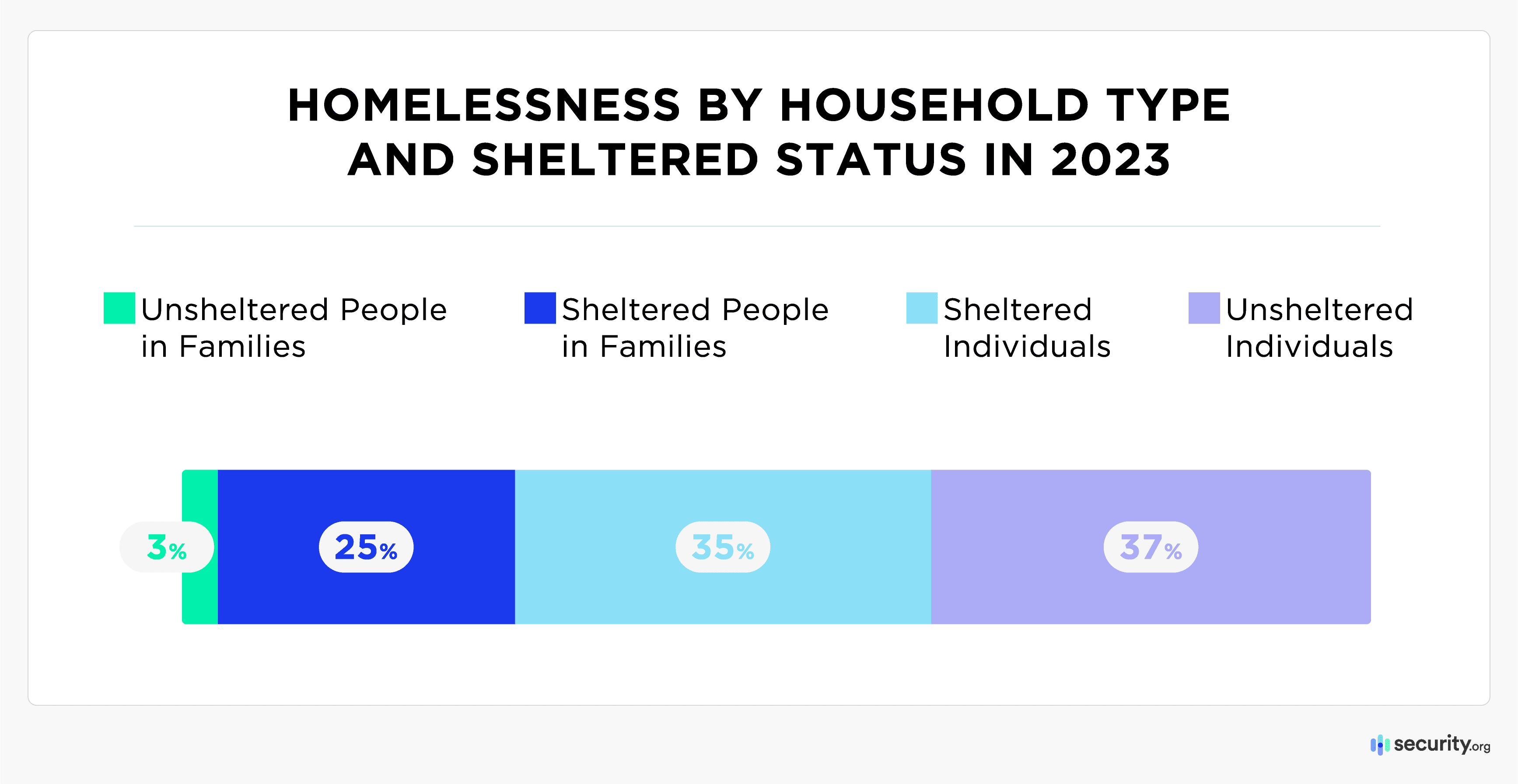

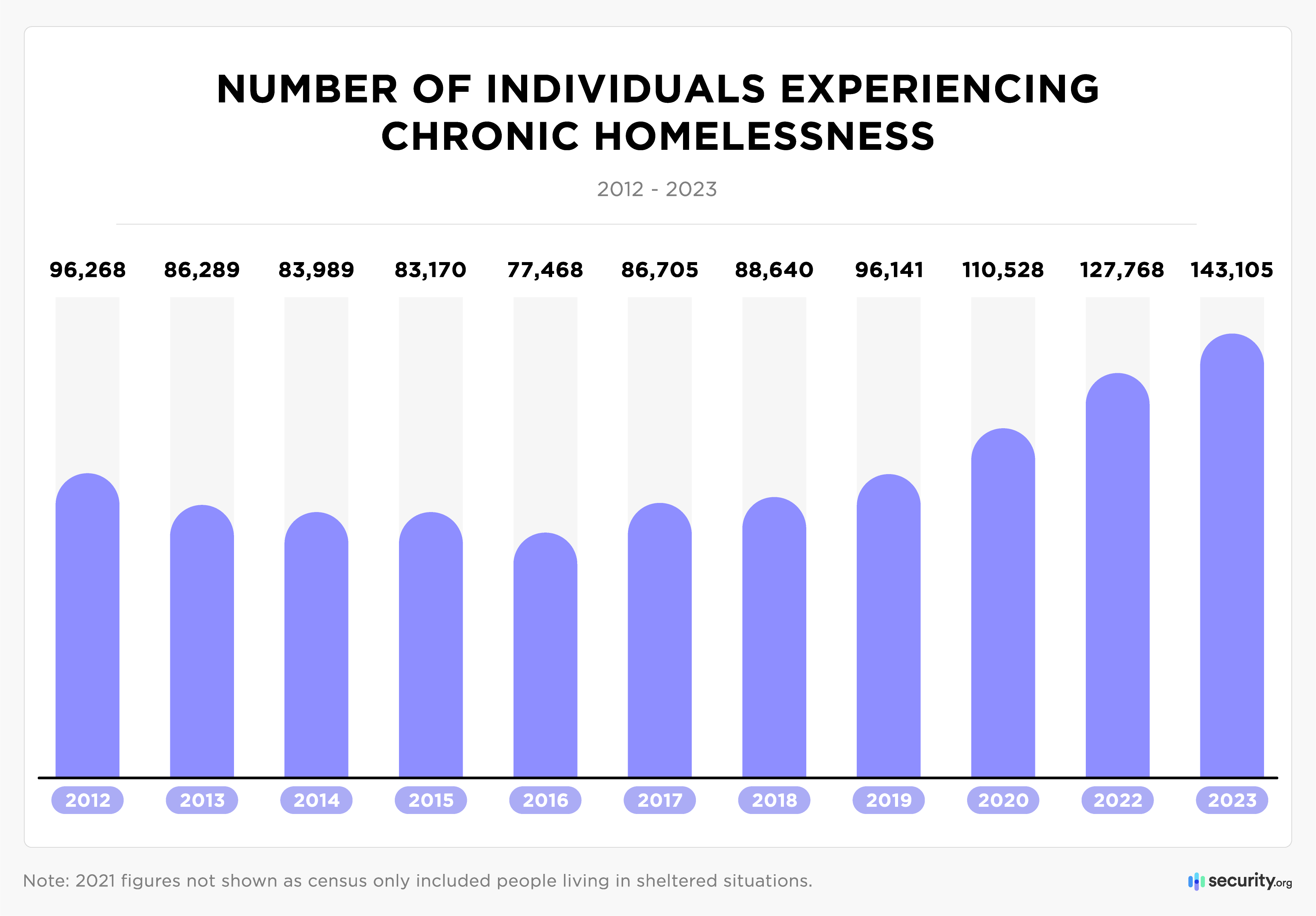

February 29, 2024 – Between 2022 and 2023, the number of people experiencing homelessness in the U.S. jumped 12 percent—the largest yearly increase since the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) started collecting data in 2007.

“We’re in a crisis right now—let’s make no mistake about that,” said Jeff Olivet, executive director of the U.S. Interagency Council on Homelessness, at February 22 virtual event co-sponsored by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health’s Initiative on Health and Homelessness (IHH) . “Housing is a basic human right, just like food or water or a right to education, a right to health care—people need and should have access to affordable housing. And yet, we know we live in a country and in a world where that’s not always the case.”

Other co-sponsors of the event included the Harvard Joint Center on Housing Studies, the Harvard Kennedy School Government Performance Lab, and the Harvard Advanced Leadership Initiative.

Howard Koh , Harvey V. Fineberg Professor of the Practice of Public Health Leadership and IHH faculty chair, served as moderator.

A multi-system failure

The homelessness crisis is driven by challenges across multiple systems, according to Olivet, who discussed key findings from the HUD 2023 Annual Homeless Assessment Report . Not only is there a shortage of affordable housing, but many people also have trouble accessing physical and mental health care, education, and public transportation.

“When you look at all of those factors, it’s no wonder that we have millions of Americans who experience homelessness,” he said.

Olivet noted that during the first couple of years of the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government instituted eviction moratoriums and provided emergency housing vouchers, but these protections and resources have since ended.

However, Olivet also highlighted a success: With bipartisan support from Congress, the number of veterans experiencing homelessness has decreased by more than 50 percent over the last decade and a half.

“It gives us a proof point that when we invest in housing and wraparound health care, that we know how to end homelessness,” he said. “The question is, how do we apply that to other populations? That’s going to take additional resources.”

Collaborative efforts

In addition to the factors that Olivet mentioned, the number of people experiencing homelessness is increasing due to an influx of immigrants from the Mexico–U.S. border, according to speaker Beth Horwitz, vice president of strategy and innovation at All Chicago Making Homelessness History. The nonprofit coordinates the efforts of organizations across the city, as well as government resources, to serve the different needs of the homeless population.

“We found that when we centralize and coordinate resources, we have the greatest impact,” she said.

Horwitz said that All Chicago expanded its efforts during the pandemic by leveraging resources from the federal government.

She added, “We’re seeing increased investments from state and local government to help us continue to serve even more people, so that we can become a country where housing is a human right, and everyone has access to safe and affordable housing,” she said.

Photo: iStock/Brett Wiatre

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Solving Homelessness from a Complex Systems Perspective: Insights for Prevention Responses

Patrick j. fowler.

1 The Brown School, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri 63130, USA; ude.ltsuw@relwofjp , ude.ltsuw@dnamvohp , ude.ltsuw@lacramek

Peter S. Hovmand

Katherine e. marcal.

2 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, Missouri 63130, USA; ude.ltsuw@yamnas

Homelessness represents an enduring public health threat facing communities across the developed world. Children, families, and marginalized adults face life course implications of housing insecurity, while communities struggle to address the extensive array of needs within heterogeneous homeless populations. Trends in homelessness remain stubbornly high despite policy initiatives to end homelessness. A complex systems perspective provides insights into the dynamics underlying coordinated responses to homelessness. A constant demand for housing assistance strains service delivery, while prevention efforts remain inconsistently implemented in most countries. Feedback processes challenge efficient service delivery. A system dynamics model tests assumptions of policy interventions for ending homelessness. Simulations suggest that prevention provides a leverage point within the system; small efficiencies in keeping people housed yield disproportionately large reductions in homelessness. A need exists for policies that ensure reliable delivery of coordinated prevention efforts. A complex systems approach identifies capacities and constraints for sustainably solving homelessness.

1. HOMELESSNESS AS A COMPLEX PUBLIC HEALTH THREAT

1.1. scope of homelessness.

Homelessness poses an enduring public health challenge throughout the developed world. Although the Universal Declaration of Human Rights declared housing a basic right in 1991, the United Nations continues to identify homelessness as an urgent human rights crisis ( 109 ). Definitions vary, but homelessness generally refers to the lack of safe accommodations necessary for respite and connection with people and places ( 11 , 47 , 110 ). Homelessness includes living on the streets or in shelters, as well as patterns of housing insecurity such as overcrowding or excessive cost burden. The most recent global survey of countries estimates that more than 1.5% of the world’s population lack basic shelter, while as many as one in five people experience housing insecurity ( 109 ).

Trends of homelessness suggest stubbornly stable or expanding rates. Most of Europe has seen large increases in rooflessness as well as housing instability in recent years ( 80 , 110 ). For instance, the homeless populations of Germany and Ireland have increased by approximately 150% from 2014 to 2016 and from 2014 to 2017, respectively ( 92 ). Point-in-time counts of homeless persons in Australia suggest increases in per capita (PC) rates from 2006 (45 per 10,000) to 2016 (50 PC) ( 3 ). The United States shows decreases in PC rates of homelessness based on annual point-in-time counts of sheltered and unsheltered persons ( 47 ); however, changes have leveled off despite substantial reorganization of homeless assistance.

Housing insecurity represents the much larger problem of hidden homelessness. On average, poor families (earning less than 60% of the median national income) in the European Union spent more than 40% of their income on rent in 2016 ( 92 ). More than 80% of US households below the federal poverty line spent at least 30% of their incomes on rent. Frequent moves and doubling up represent additional common indicators of inadequate housing ( 20 ). Foreclosure and evictions are endemic in certain communities; estimates suggest that nearly one million US households experienced eviction in 2016, while eviction represents a major challenge across Europe ( 23 , 53 ). Trends demonstrate the challenges of solving homelessness and the need for innovations.

1.2. Impact of Homelessness

Homelessness and associated poverty have life course implications for physical and mental health. Many adverse health and socioemotional outcomes are linked to homelessness in children ( 26 , 117 ). Homeless adults face increased mortality from all causes, and those with severe mental illness display significantly worse quality of life compared with nonhomeless individuals with mental illness ( 61 ). Education levels and employment rates among homeless adults are low compared with the general population ( 9 , 16 ). In Europe, average life expectancy of people who experience homelessness is 30 years less than nonhomeless populations ( 11 ).

In addition to human suffering, public expenditures associated with homelessness are substantial. In the United States, estimated costs (all adjusted to 2018 USD) of a homeless shelter can exceed $7,000 per month per family ( 19 , 45 , 98 ) with additional costs attributed to inpatient hospitalization, incarceration, and public assistance ( 36 , 99 ). Cost estimates in Europe are limited but suggest substantial expenditures associated with shelter and outside services such as emergency departments, psychiatric care, and jail or prison ( 78 ). In Australia, the government estimates spending at $30,000 per homeless person per year ( 4 ). Few rigorous studies quantify the additional social losses in productivity and well-being. Communities around the world struggle to manage the human and financial burdens of homelessness.

2. COMPLEXITY IN CAUSES AND RESPONSES TO HOMELESSNESS

2.1. complex causes of homelessness.

Experiences of homelessness depend on a complex interplay between individual, interpersonal, and socioeconomic factors. Research has long identified mental illness and addiction as risk factors for homelessness ( 37 , 47 , 48 ). Personal struggles also strain interpersonal relationships with family, friends, and romantic partners; in a vicious cycle, conflict undermines well-being as well as erodes potential housing supports ( 21 , 77 ). However, socioeconomic factors often dictate the likelihood of displacement.

Globally, marginalized communities disproportionately experience homelessness. Homelessness is much more common among the poor and minorities in terms of race/ethnicity, sexual orientation and identity, and institutionalization and among those with physical and mental disabilities compared with the general population ( 105 ). For instance, members of Aboriginal communities in Australia comprise a quarter of people receiving homeless services, while representing less than 3% of the total population ( 3 ). A similar disparity exists in Canada, with Indigenous people 10 times more likely to use homeless shelters than non-Indigenous ( 37 , 91 ). Due to structural inequalities associated with marginalization, the accessibility of jobs and affordable housing remains constrained; availability of appropriate accommodations is more or less random ( 11 , 74 ). Household-level shocks to housing stability such as job loss, termination of assistance, or eviction require a scramble for housing that may or may not be available, given market constraints. Homelessness results when other formal or informal housing supports remain inaccessible; lack of supports can reinforce vulnerability to crises that threaten stable housing. Thus, entries as well as exits into homelessness among vulnerable populations become a matter of bad timing and bad luck. The presence of personal and interpersonal barriers exacerbates vulnerabilities but fails to explain homelessness.

2.2. Implications of Complexity for Homeless Responses

Complexity underlying housing insecurity carries important implications for systematic responses to homelessness. First, extensive heterogeneity exists in homeless populations and in the types of services needed to address housing instability. Individuals with severe mental illness, for example, may require ongoing intensive supports to avoid falling back into homelessness, whereas pregnant teens with few connections to supportive adults have a different set of needs. This variation requires considerable flexibility and tailoring of resources to promote stability.

A related implication concerns variation in the timing and patterns of homelessness. Some households experience single episodes of homelessness, while chronic homelessness refers to instability for more than two years (one year for families with children) with ongoing barriers to stability [HEARTH Act of 2009 (Pub. L. 112–141)]. Research that investigates patterns of housing insecurity reveals distinct subpopulations based on housing trajectories ( 18 , 31 , 33 , 106 ). For instance, studies show that chronic patterns of homelessness affect a relatively small number of persons ( 33 , 34 ). Homeless assistance continuously interacts with households at different stages of different trajectories, which makes accurate prediction of risk as well as response to interventions exceedingly difficult ( 5 , 38 , 44 , 58 , 95 ).

The complex causes of homelessness require complex solutions. Homeless assistance typically requires the provision of multifaceted supports that adapt in response to shifting household demands and often includes unique combinations of residential and nonresidential supports. Recurrent constraints on the availability of supports often require further tailoring of homeless assistance on the basis of resource accessibility. The resulting combinatorial complexity of housing interventions challenges sustained, systematic responses to homelessness ( 35 ).

Finally, the complex causes of and responses to homelessness present substantial challenges for screening and resource allocation. Efficient service provision depends on accurate assessments of risk and potential responses to interventions ( 10 , 58 , 72 ). Tools, such as the Vulnerability Index—Service Prioritization Decision Assistance Tool (VI SPDAT), purport to categorize households seeking homeless assistance for appropriate interventions from responses to screening questions; high vulnerability requires supportive housing, moderate requires temporary housing with less intensive supports, and households with low risk are diverted from the system ( 22 ). VI SPDAT developers report item reliability and claim use in communities around the world ( 75 ). However, little evidence exists on the tool’s accuracy, and available research suggests poor sensitivity and specificity with common scoring procedures ( 7 , 15 ). The VI SPDAT intervention assignments poorly differentiate households, resulting in extensive false positives (false alarms) and false negatives (missed hits) ( 6 , 108 ). Other screening tools show similar challenges for targeting preventive services ( 13 , 28 , 44 , 94 ). The difficulty in prediction reflects the complexity that underlies homelessness ( 5 , 38 , 58 ).

2.3. Complex Systems and Coordinated Responses to Homelessness

Nations have adopted various strategies to address homelessness. Responsibility for serving homeless populations in European Union nations generally falls under common social welfare policies, while federal policies and funding structure local responses to homelessness in Australia, Canada, and the United States (11, 116; Pub. L. 112–141). Although communities differ in how supports are organized, a common structure connects the delivery of homeless assistance. Delivery of housing plus supports leverages interorganizational networks composed of governmental and nongovernmental agencies ( 10 , 41 , 81 , 87 ). Formal and informal partnerships work together to screen and respond to individuals and families experiencing housing crises.

Figure 1 illustrates the underlying framework for homeless services from a complex systems perspective. In the center, households experience countervailing supports and strains that influence stability, represented as virtuous and vicious cycles. When strains exceed supports, a need for housing triggers the demand for homeless assistance. Access to homeless services depends on local and national contexts; formal and informal policies determine eligibility, timing, and funding of resources, while socioeconomic conditions influence demand chains for services ( 27 , 74 ). The resulting dynamics allow homeless services to adapt and evolve over time.

Coordinated responses to homelessness as a complex system. Solid lines reflect a treatment first approach, whereas dashed lines represent housing first philosophy. Circular nodes represent examples of key supports in keeping people housed; ties between nodes generally refer to information exchanges, such as communications, service referrals, or funds. The + and − signs indicate the direction of correlation between variables.

The top layer in Figure 1 represents the general structure of homeless or residential services. Although heavily based on a North American perspective, the model captures a number of common elements in local and national responses to homelessness ( 10 , 11 , 25 ). Screening aims to identify need and allocate households to the most appropriate and available service. Emergency responses address immediate housing crises; in many countries, this represents homeless shelters that provide short-term accommodations. Temporary housing provides time-limited accommodations with case management and other nonresidential services. Supportive housing refers to permanent connection to housing plus case management to address substantial barriers to stability. Rapid rehousing and homelessness prevention represent efforts to provide immediate access to stable accommodations.

Movement through the system depends on organizing philosophies for solving homelessness. Screening attempts to forecast the level of need, ranging from low (prevention), moderate (rapid rehousing), and high (supportive housing) risk for ongoing homelessness ( 75 ). Treatment first assumes people need services to address the underlying barriers that led to homelessness ( 88 , 107 ). A staircase model structures services so that households progress from shelters to temporary housing in addition to the provision of services to permanent supportive housing. Transitions expose people to higher levels of supports that make them more prepared for stable housing. In contrast, housing first considers stable accommodations as a precondition for any treatment needed to reduce homelessness ( 107 ). The structure of residential services attempts to place people in stable housing as quickly as possible.

The bottom layer in Figure 1 illustrates the extensive networks of formal and informal supports engaged in addressing household instability. Conceptually, connections can be informal interpersonal communities or formalized through agreements and contracts. Homeless services at the hub denote efforts to weave a safety net of supports for households. Systems vary in the extent to which nonresidential supports are specific to the residential service or carry over with households as they transition into and out of homelessness ( 11 , 30 ). Regardless, homeless systems rely on extensive cross-systems collaboration to promote stability and remove barriers that prolong homelessness ( 10 , 19 , 90 ).

Use of interagency networks responds to the complexities of addressing homelessness. Foremost, referral networks allow for quicker access to a wide range of supports, which can handle the extensive heterogeneity of needs among homeless populations. Networks also provide flexibility to expand and contact with shifts in demand for services ( 10 , 19 , 73 , 87 ). A timely example concerns displacement due to conflict that triggers surges in refugee populations with various needs within a community or country; Germany, for example, saw a 150% increase in homelessness from 2014 to 2016 composed primarily of refugees ( 92 ). In times of greater need such as an influx of refugee families, interagency networks allow for sharing information and resources to respond more quickly. Likewise, collaborative organizations avoid hierarchal approval processes; instead, decision making on service delivery is distributed across providers within agencies that potentially speed up resource allocations ( 82 ). A network structure provides a dynamic and adaptive response to homelessness.

Collaborative networks introduce their own complexities for homeless service delivery. Actual efficiencies of the system depend on the mutually agreed upon rules that drive resource allocation ( 8 , 82 ). Partnerships must continuously devote time toward planning and monitoring mutually agreed upon goals, which shifts resources away from the core service missions of each agency ( 35 ). Given the constant pressure for social services, a dynamic emerges that threatens continued investment in collaboration ( 59 ). Instability can create oscillations in the quality of network performance toward ending homelessness ( 35 ). Virtuous cycles emerge within collaborations that have clear goals, strong leadership, and investments in backbone supports ( 62 ). Challenges exist for sustainable efforts.

Taken together, coordinated approaches to homelessness must consider the extensive heterogeneity in the population, as well as in the types and timing of services. Given the multiple pathways into homelessness and the diversity of the homeless population, a one-size-fits-all approach is inadequate. Collaborations represent a flexible strategy to address homelessness. However, system performance toward ending homelessness depends in large part on continuous investments in partnerships.

3. TRANSFORMING COORDINATED RESPONSES TO HOMELESSNESS

3.1. housing first as an organizing philosophy.

The complex systems delivering homeless assistance organize around key theories on ending homelessness. Formal and informal policies operationalize these theories, and structure emerges to coordinate resource allocation across intersecting networks ( 8 ). A paradigm shift has moved homeless systems toward a housing first philosophy ( 76 ). Although housing first also refers to a specific case management intervention, the philosophy more generally aligns services to stabilize accommodations quickly and without preconditions. This approach contrasts with the earlier treatment first, or staircase, approach that require homeless persons to demonstrate housing readiness or compliance with service plans as a condition of obtaining and maintaining housing supports. Fundamentally, the shift in philosophies moves toward a person-centered and recovery-oriented approach that assumes housing serves as a platform for reintegrating into communities.

Housing first interventions provide access to housing plus ongoing supports ranging in duration and intensity ( 11 , 107 ). Examples include assertive community treatment (ACT), critical time intervention (CTI), and Pathways to Housing. Early experimental studies in the 1980s and 1990s showed that homeless persons experiencing severe mental illness achieved stability more quickly and more consistently when randomly assigned to housing first instead of to treatment first services ( 87 , 102 ). Moreover, early studies suggested that the delivery of case management yielded savings from avoided costs for shelter, hospitalization, and criminalization ( 51 , 85 ). The initial evidence challenged assumptions of housing readiness to highlight cheaper and more effective options for homeless service delivery.

Well-designed studies subsequently tested the implementation and impact of housing first models with different homeless populations. Several large experiments in the United States and Canada randomly assigned homeless individuals and families to different housing interventions and carefully monitored the impacts of service delivery on a host of outcomes ( 2 , 45 , 87 ). Evidence from these and other studies generally support permanent housing approaches for improving stability ( 84 ). Benefits of permanent housing on well-being and quality-of-life improvements are more elusive; treatment effects are smaller and less consistent across outcomes and populations ( 32 , 45 ). Additionally, emerging evidence on rapid rehousing interventions providing time-limited rental assistance shows little impact on stability or well-being ( 14 , 45 , 58 ). As a whole, the body of evidence firmly dismisses housing readiness requirements for homeless assistance.

3.2. Dissemination and Implementation of Housing First

Numerous rigorous investigations into widespread dissemination and implementation of housing first provide important considerations for complex homeless systems. Studies show that fidelity to specific housing first models promotes household outcomes ( 2 , 40 , 87 ). Yet, model adherence requires substantial investment in training and technical assistance ( 2 , 40 , 69 ). Using the interactive systems framework ( 115 ), a national rollout of Pathways to Housing in Canada showed that fidelity diminished in communities with less initial buy-in and support ( 2 , 69 ).

Similar findings emerged from an initiative to provide housing first to 85,000 veterans across the United States ( 55 , 56 ). The organizational transformation model ( 63 ) directed substantial investment and technical assistance to deliver supportive housing as part of the health care system for veterans. Housing readiness requirements diminished through transformational efforts; however, model fidelity for client-centered supportive services remained inconsistent ( 54 ). Both studies emphasize the necessity of strong leadership and buy-in for achieving housing first model adherence ( 2 , 39 , 40 , 54 ). The studies show the difficulty in shifting cultures toward housing first principles even in well-resourced initiatives.

Systems integration of services for housing first also proves challenging. An innovative early experiment of supportive housing for homeless individuals experiencing severe mental illness also tested impacts on systems of care ( 43 ). The study randomly assigned individuals to receive supportive housing, as well as communities to receive technical assistance for systems transformation to integrate services. Community-level interagency networks were assessed over time to see if resources for supportive housing triggered new and stronger partnerships for nonresidential services. Findings suggested little change in systems of care, and technical assistance failed to integrate services ( 73 , 86 , 88 ).

3.3. Housing First Adoption and Adaptations

Despite implementation challenges, the housing first philosophy has been broadly adopted within homeless services around the world ( 11 , 76 ). This shift is most apparent in the integration of housing first principles into national strategies for addressing homelessness in Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, France, Finland, Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Scotland, Spain, Sweden, and the United States ( 76 ). Policies focus on the provision of housing as a platform for connection to other services necessary for ending homelessness ( 79 , 112 ). However, considerable variation exists in adherence to evidence-based interventions as well as adaptations for system-wide implementation ( 11 , 76 ).

The United States provides an example of both broad adoption and adaptations of housing first philosophy. The Homeless Emergency Assistance and Rapid Transition to Housing (HEARTH) Act of 2009 (Pub. L. 112–141) introduced federal legislation that required every community across the country to develop and implement coordinated responses to homelessness. Guided by housing first principles, policies focus on procedures for community-wide screening and allocation of homeless assistance based on level of need; resources are prioritized for homeless persons deemed most vulnerable ( 62 , 113 ). The emphasis on vulnerability coincides with a shift in resources toward the literal homeless and away from the broader demand for supports to maintain housing ( 10 , 19 , 94 ). The housing first tenets were codified in a redefinition of homelessness and eligibility for services, as well as national agendas for ending homelessness ( 113 ; Pub. L. 112–141).

Figure 2 illustrates the implementation of housing first policies through shifts in new and reallocated resources. Plotting year-round beds available for homeless persons since 2007, the system has increasingly used housing first rapid rehousing and supportive housing, whereas use of shelters and temporary housing has declined. Trends in total federal funding for homeless assistance also demonstrate increases in capacities. Although annual budgets fail to disaggregate funds by service type, increases in funding correspond with shifts toward rapid rehousing and supportive housing. Decreases in the number of persons served through homeless assistance over the same period further suggest that the homeless systems provide more intensive services ( 46 ).

Capacity trends of homeless assistance in the United States. Bars indicate the number and type of year-round beds according to Continuum of Care Housing Inventory Counts; the red trend line represents overall federal funding of homeless services through the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Veterans Affairs (VA), and Community Development Block Grants (CDBG). Other abbreviations: ES, emergency shelter; OPH, other permanent housing; PSH, permanent supportive housing; SH, safe haven.

3.4. Housing Insecurity and Coordinated Responses to Homelessness

Capacity shifts also signal the role of housing insecurity in the coordinated response to homelessness. Although US policy requires communities to include prevention in coordinated responses to homelessness, the availability and funding for such efforts are not tracked. Moreover, annual assessments of homeless system performance required by federal regulations do not consistently measure successful prevention efforts (Pub. L. 112–141). A similar pattern emerges in countries across the world; European countries that record funding show disproportionate spending on homeless interventions relative to prevention ( 66 , 78 ). Only Wales systematically monitors the total demand and response to prevention services ( 66 , 68 ). In the absence of metrics that track the implementation and outcomes of prevention, it is difficult to understand how well-coordinated responses address overall demand for homeless assistance.

Crises in affordable housing throughout the United States and globally suggest widespread unmet demand. Figure 3 , for instance, presents an indicator of housing insecurity in the United States. The figure plots the annual number of renting households paying more than 50% of income toward rent, referred to as severe rent burdened ( 111 ). A spike of 10 million households in 2012 has declined in recent years, and the trend line of severely burdened as a proportion of all renting households suggests some relief for the lowest-income households. Yet, reductions have yet to return to prehousing crises levels ( 52 ). Markets around the world face similar shortages in affordable housing that create a constant demand for homeless assistance ( 27 , 60 , 92 ).

Number ( blue bars ) and percent ( red line ) of households in the United States with severe rent burden 2007–2017. Data obtained from the American Community Survey 1-year estimates ( 111 ).

3.5. Prevention in Coordinated Responses to Homelessness

The lack of focus on housing insecurity reflects ambivalence in national policies regarding prevention ( 67 ). On one hand, most countries emphasize prevention as a key component of housing first strategies ( 11 , 37 , 66 , 113 ). Prevention frameworks are based on a public health conceptualization of homelessness and generally refer to policies and practices that promote connections to stable homes ( 37 , 67 , 94 ). As illustrated in Figure 4 , prevention efforts target populations at varying levels of risk for homelessness with evidence-based resources that increase in intensity ( 42 , 67 , 94 ). Universal prevention is broadly available to ensure access to housing, such as the right to housing legislation that guarantees access to housing supports, as well as duty to assist policies that require governments to respond to requests for housing supports ( 11 , 67 , 103 ). Selective prevention targets resources toward groups vulnerable for homelessness, for instance families under investigation for child maltreatment, youth aging out of foster care, and veterans returning from combat ( 14 , 32 , 33 ). Indicated prevention focuses on populations demonstrating vulnerability for homelessness, such as households facing evictions and foreclosures and low-income families screening high for housing instability ( 44 , 95 , 114 ). Coordinated prevention initiatives combine multiple intervention types to stem the inflow into homelessness. National policies aspire to avoid human and social costs through timely assistance that addresses housing insecurity.

Homelessness prevention targets based on population and intensity of housing supports.

On the other hand, policy agendas struggle to reconcile aspirations with the feasibility of meeting the broad demand posed by housing insecurity ( 11 , 19 , 67 ). Prevention proves challenging, given the difficulty in predicting whether timely assistance averts homelessness that would have occurred otherwise; inefficiencies in targeting create false alarms that diminish cost-effectiveness ( 12 , 94 , 95 ). Moreover, prevention efforts that fail to address societal determinants of homelessness—including structural poverty, violence, and marginalization—are perceived as misguided ( 12 , 94 ). In the context of scarcity, persuasive arguments suggest a responsibility to deliver services for households most likely to avoid homelessness and associated costs ( 12 , 19 , 94 ). Prevention efforts shift toward avoiding reentry into homelessness instead of promoting connections to housing ( 14 , 67 , 104 ).

Policy ambivalence results in inconsistent applications of prevention across countries ( 67 ). Debates over prevention-oriented approaches to homelessness have persisted over three decades ( 19 , 50 , 94 ). Few national strategies currently include structured processes for delivering and monitoring prevention activities, and instead, countries vary considerably in basic definitions on targeting of services ( 67 , 68 ). In the United States, coordinated responses allow allocation of homeless funds for prevention without guaranteeing access. Even most communities that recognize housing as a basic right ensure only connection with supports (regardless of appropriateness and legality) and not accommodations ( 12 , 67 ). Homeless assistance relies on diverting demand driven by housing insecurity toward community-based services and other social welfare resources outside of homeless systems ( 12 , 19 , 72 ). If the adage that what gets measured gets done is correct, the lack of accountability reveals the unsystematic role of prevention within coordinated responses to homelessness ( 67 , 68 ).

4. SOLVING HOMELESSNESS FROM A COMPLEX SYSTEMS PERSPECTIVE

4.1. homeless assistance from a complex systems perspective.

Complex systems provide a critical perspective on the delivery of coordinated responses to homelessness. Complex systems are composed of multiple interacting agents that produce nonlinear patterns of behaviors, and they continually adapt and evolve in response to conditions within the system ( 24 , 64 , 93 , 101 ). Dynamics emerge from feedback mechanisms, influencing future system behaviors. Reinforcing feedback generates patterns of growth (positive or negative), whereas balancing feedback limits unconstrained growth (homeostasis). Interactions between feedback processes often produce counterintuitive results when trying to change a system. Given the nature of homelessness, complex systems offer a unique tool for evaluating coordinated responses.

Complexity characterizes homelessness and systematic responses. At the household level, transitions between stable and unstable accommodations create oscillations over time that characterize homelessness ( 83 , 89 , 96 ). The patterns challenge accurate predictions and effective responses to homelessness ( 38 , 44 , 95 ). The elaborate ties across persons, agencies, and service systems enable extensive customization to unique and dynamic demands for services ( 1 , 57 , 81 ).

A complex systems perspective offers insights into sustainable solutions to homelessness. Framed as a dynamic problem ( 49 , 100 ), total homelessness is a function of the initial levels plus the ongoing movement of people in and out of homelessness. Mathematically, the dynamic is articulated in the differential equation:

where d represents change, homelessness represents total persons homeless, t represents time, entries represents persons entering homelessness at a given time, and exits represents persons exiting homelessness at a given time. Homelessness trends depend on the population size plus the rate of entries and exits over time. This stock-and-flow dynamic is analogous to water levels in a bathtub and produces counterintuitive results ( 100 , 101 ). For instance, to drain a tub, the volume of water from the tap must be less than the volume of outflow after pulling the stopper. Thus, water levels will continue to rise after opening the drain completely without also closing the tap. Likewise, closing the tap will raise water levels if the drain remains blocked. As anyone who has dealt with an overflowing toilet knows, the complexity can trigger poorly timed and counterproductive reactions.

Community-wide coordinated responses to homelessness attempt to manage stock-and-flow dynamics under conditions of far greater uncertainty. Efficient solutions likely address the net flow of homelessness, as opposed to one part of the system. However, the interacting processes that respond to the need for homeless assistance (see Figure 1 ) produce nonlinearities that obscure optimal choices for system-wide strategies ( 71 , 100 ). A number of common results from intervening in complex systems challenge decision making, such as delayed effects, tipping points, and worse-before-better scenarios ( 100 ). The dynamics make decisions about resource allocation toward housing first adaptations or prevention approaches difficult.

4.2. A System Dynamics Model of Coordinated Responses to Homelessness

A system dynamics model allows investigation into coordinated responses to homelessness. The systems science method uses informal and formal models to represent complex systems from a feedback perspective ( 49 , 64 , 100 ). Computer simulations test assumptions of the system, as well as help identify leverage points that represent places to intervene in the system for maximum benefit ( 70 ).

Figure 5 represents a dynamic hypothesis for solving homelessness. Historical trends present the annual number of persons receiving homeless services in the United States ( 97 ). Hoped and feared trajectories represent theorized responses to homelessness. The trajectories define the dynamic problem as a need for innovative policies that disrupt the status quo ( 49 , 67 , 100 ). Although the example uses annual national data on homeless persons served in the United States, similar hopes and fears likely emerge in many local and national contexts ( 35 ).

Dynamic hypothesis of coordinated responses to homeless in the United States. Historical trends ( black ) present the annual number of persons receiving homeless services. Hoped ( blue ) and feared ( red ) trajectories represent theorized responses to homelessness. Based on trends in the United States, the vertical axis reports the number of persons served by homeless assistance annually, whereas the horizontal axis represents time as 10 years in the past and future. The left half of the graph shows the observed linear decline in homeless, which is interpreted as progress ( 97 ). The right half of the graph articulates the hopes and fears of coordinated responses to homelessness.

Policy shifts toward housing first adaptations as well as prevention-oriented approaches hypothesize a sharp and sustainable downward trajectory of homelessness. However, the mechanisms underlying the dynamic differ on the basis of philosophy. Housing first adaptations assume moving more homeless persons into stable housing more quickly will drive down demand for homeless assistance, whereas prevention-oriented approaches hypothesize that supports provided before homelessness will reduce demand. A third hypothesis from a complex systems perspective suggests that a combination of approaches disrupt homeless trajectories. Articulating the theories of change allow researchers to model the dynamics.

Figure 6 presents an informal model of coordinated responses to homelessness. The structure elaborates on the previous formulation to capture stock-and-flow dynamics, and a formal computational model incorporates additional differential equations to capture dynamics ( 100 ). Using system dynamics conventions, stocks refer to accumulations of people, whereas flows represent transitions in and out of stocks. People exit stocks into stable housing defined as not needing housing assistance. In addition to homelessness, the model tracks individuals experiencing housing insecurity who are seeking assistance versus hidden homeless, which incorporates the different targets of prevention. Dynamics emerge as people transition in and out of stable housing. The model assumes that the average time in homeless assistance is 3.5 years, and housing insecurity represents a transitional state through which most exit within two years, loosely based on definitions of chronic homelessness ( 97 ).

System dynamics model of people receiving homeless assistance and those experiencing housing insecurity and hidden homelessness. Boxes represent accumulations of people, arrows represent transitions in and out of stocks, and clouds represent stable housing.

Computer simulations test a series of policy experiments for solving homelessness. The first experiment tests efforts to improve housing first by decreasing time spent in homeless assistance before exiting to stability. The second experiment expands universal, selective, and indicated prevention by reducing each inflow into homelessness assistance. The third experiment tests combined housing first and prevention strategies. Each experiment improves performance by 50%, and combined interventions do not exceed 50% effects. All analyses were conducted within Stella Architect Version 1.2.1. A web-interface provides access to the model and allows real-time experiments ( https://socialsystemdesignlab.wustl.edu/items/homelessness-and-complex-systems/ ).

4.3. Simulation Results

Initial analyses assessed confidence in the model. Simulations replicate observed trends in persons seeking homeless assistance ( Figure 3 ) and housing insecurity ( Figure 2 ) in the United States between 2007 and 2016. Moreover, exploratory analyses suggest that the model is insensitive to initial values; similar patterns emerge when increasing stocks and reducing transition times ( 100 ). Different indicators of homelessness and insecurity produce similar results, which further suggests that the model captures the population-level dynamics of homelessness.

Figure 7 displays results from policy experiments on trends of homeless assistance and total housing insecurity (seeking assistance plus not seeking assistance). Findings demonstrate support for the complex systems perspective. Optimizing housing first approaches results in incremental reductions in the number of persons in homeless assistance with no impact on the rates of housing insecurity; results suggest that the system is already optimized for reducing homelessness quickly, and it currently strains to keep up with the constant demand for homeless assistance. By reducing the demand for homeless assistance, prevention improvements qualitatively shift the trajectory of housing insecurity, while generating similar incremental improvements in homeless assistance trends as housing first optimization. The same shifts occur when experimenting with smaller improvements in efficiencies; prevention always outperforms housing first adaptations. For instance, a 5% improvement in prevention generates a similar decrease on total need for housing as a 5 0% improvement in housing first adaptations. Thus, prevention represents a leverage point to enhance coordinated responses to homelessness, and tests reveal that universal plus indicated preventions account for the greatest shifts. However, the optimal response to homelessness comes from a multipronged approach that incorporates prevention with housing first, which generates shifts in housing insecurity and homeless assistance. As hypothesized by the complex systems perspective, managing the net flow achieves desired outcomes of moving toward solving homelessness.

Policy experiments showing the impact of housing first and prevention efforts on the number of people in homeless assistance ( a ) and number of hidden homeless ( b ) with services as usual ( dark blue line ); housing first only ( light blue line ); universal, selective, and indicated prevention ( red line ); and housing first plus universal, selective, and indicated prevention ( yellow line ).

Results must be considered in context. Simulations use US national data to build confidence that the model replicates trends; however, the forecasts are not meant as point estimates for planning purposes. Likewise, national data aggregate across communities that may experience different outcomes from coordinated responses. Using local data and different indicators of system performance would improve confidence in the simulation, as well as in the dynamics of homeless assistance. Finally, the simulations fail to provide an oracle; malleability exists in how policy responds and adapts to trends in homelessness that may alter the system dynamics. The models also make no assumptions about the implementation of prevention. Reducing demand by 50% may exceed realistic expectations, and the simulations fail to consider policy resistance generated from current paradigms. Regardless, simulations suggest small improvements in prevention generates qualitative shifts in demand for assistance.

4.4. Implications for Coordinated Responses to Homelessness

Homeless systems across the world are optimizing policies toward solving chronic homelessness. Resource allocation increasingly prioritizes on the basis of vulnerability and moral preference (e.g., households with children, veterans, seniors). However, simulations warn of unintended consequences that arise from constant pressure for stable housing. Systems that focus on the most vulnerable risk ignoring the unseen needs of the many households unable to access timely supports. Effective responses need to manage both the inflows and outflows to produce intended declines in homelessness rates.