- Oxford Thesis Collection

- CC0 version of this metadata

The right to receive assistance in suicide and euthanasia, with particular reference to the law of the United States

Whether to legalize assisted suicide and euthanasia is among the most hotly debated legal and public policy issues today in the United States, as it is in many countries. In this Thesis, I first (in Chapters I and II) isolate the critical questions in this debate, the answers to which will likely determine the fate of assisted suicide and euthanasia in America's courts and legislatures: Is there historical precedent for allowing the practices? Do fairness concerns dictate that we ...

Email this record

Please enter the email address that the record information will be sent to.

Please add any additional information to be included within the email.

Cite this record

Chicago style, access document.

- MS.D.Phil.c.19040_ocr.pdf (pdf, 381.5MB)

Why is the content I wish to access not available via ORA?

Content may be unavailable for the following four reasons.

- Version unsuitable We have not obtained a suitable full-text for a given research output. See the versions advice for more information.

- Recently completed Sometimes content is held in ORA but is unavailable for a fixed period of time to comply with the policies and wishes of rights holders.

- Permissions All content made available in ORA should comply with relevant rights, such as copyright. See the copyright guide for more information.

- Clearance Some thesis volumes scanned as part of the digitisation scheme funded by Dr Leonard Polonsky are currently unavailable due to sensitive material or uncleared third-party copyright content. We are attempting to contact authors whose theses are affected.

Alternative access to the full-text

Request a copy.

We require your email address in order to let you know the outcome of your request.

Provide a statement outlining the basis of your request for the information of the author.

Please note any files released to you as part of your request are subject to the terms and conditions of use for the Oxford University Research Archive unless explicitly stated otherwise by the author.

Contributors

Bibliographic details, item description, terms of use, views and downloads.

If you are the owner of this record, you can report an update to it here: Report update to this record

Report an update

We require your email address in order to let you know the outcome of your enquiry.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Op-Ed Contributor

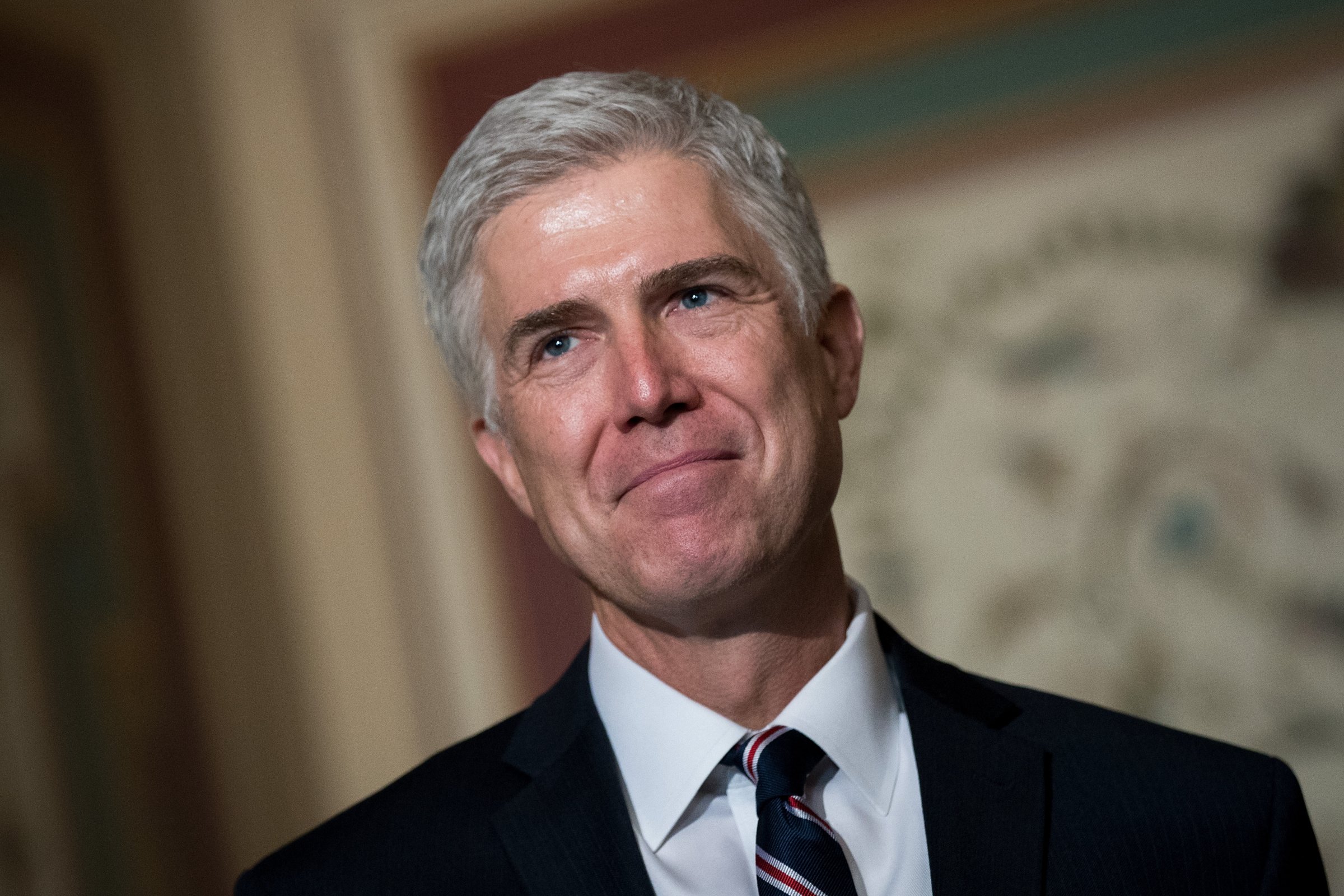

Gorsuch, Abortion and the Concept of Personhood

By Corey Brettschneider

- March 21, 2017

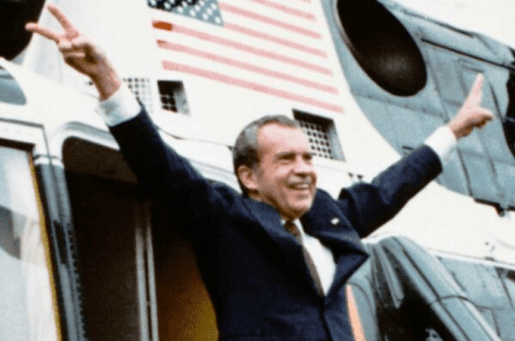

Judge Neil M. Gorsuch has written little about abortion, and we do not know whether he would vote to overturn Roe v. Wade, the 1973 Supreme Court decision that established abortion as a fundamental right. But he has expressed a position on two related subjects, assisted suicide and euthanasia. In his Oxford dissertation and a later book, he defended the inviolability of human life. He rejected the role of states in granting the terminally ill a right to die and offered a legal framework that could be applied to abortion.

Judge Gorsuch, who is President Trump’s nominee to fill the Supreme Court seat vacated by Justice Antonin Scalia’s death last year, argued in both his dissertation and his book, “The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia,” that the Constitution requires banning doctor-assisted suicide and euthanasia nationwide, with a few possible exceptions. He asserted that allowing these practices in any state would violate the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection. Such a law would treat “the lives of different persons quite differently” by prohibiting the murder of the healthy while allowing the killing of the sick, he wrote.

Judge Gorsuch has clearly thought long and hard about matters of life and death. Would he extrapolate to abortion his views on assisted suicide or euthanasia? It’s not clear. In his dissertation, his limited remarks on Roe are skeptical; he calls its logic a “hodgepodge of doctrines and theories” and refers to abortion as a “nontextual right,” meaning it has no basis in the text of the Constitution. However, as Amy Howe of Scotusblog noted recently , he “has not ruled on any cases directly involving abortion during his 10 years” as an appeals court judge.

But he has had much to say in his writings about human personhood and the inviolability of life, views that are worth exploring. What gives individuals such an inviolable right, he has reasoned, is a status that legal scholars call “constitutional personhood,” defined by the 14th Amendment. Under that amendment, a state is prohibited from denying any constitutional person “life, liberty or property, without due process of law,” and cannot “deny any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

The Roe decision expressly excluded human fetuses from that definition. As the court put it in 1973 , “the word ‘person,’ as used in the 14th Amendment, does not include the unborn.” But if the Supreme Court were ever to recognize fetuses as constitutional persons, however unlikely that might seem now, then under Judge Gorsuch’s framework, the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause would require that they be entitled to the same legal protection as constitutional persons. Laws that prohibit murder thus would have to be extended to them.

Judge Gorsuch has said as much himself. In his book, he wrote, “Abortion would be ruled out by the inviolability-of-life principle I intend to set forth if, but only if , a fetus is considered a human life.” He noted that had the court “found the fetus to be a ‘person’ for purposes of the 14th Amendment, it could not have created a right to abortion because no constitutional basis exists for preferring the mother’s liberty interests over the child’s life.”

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

| Format | |

|---|---|

| BibTeX | View Download |

| MARCXML | View Download |

| TextMARC | View Download |

| MARC | View Download |

| DublinCore | View Download |

| EndNote | View Download |

| NLM | View Download |

| RefWorks | View Download |

| RIS | View Download |

Browse Subjects

- Assisted suicide Moral and ethical aspects">Moral and ethical aspects Moral and ethical aspects > United States.">United States.

- Assisted suicide Law and legislation">Law and legislation Law and legislation > United States.">United States.

- Euthanasia Moral and ethical aspects">Moral and ethical aspects Moral and ethical aspects > United States.">United States.

- Euthanasia Law and legislation">Law and legislation Law and legislation > United States.">United States.

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Neil Gorsuch

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- First Liberty Institute - Supreme Court Justice Neil Gorsuch

- Colorado Encyclopedia - Neil Gorsuch

- The Guardian - Who is Neil Gorsuch? A staunch conservative with a background to worry liberals

- Oyez - Biography of Neil Gorsuch

- Neil Gorsuch - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Religion and Politics

A Project of the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics

Washington University in St. Louis

The Bioethics of Neil Gorsuch

- --> --> -->

- Email Email -->

(Getty/Justin Sullivan)

I n his Senate confirmation hearings, Neil Gorsuch gave little away. His extensive but ultimately unrevealing answers to senators’ questions did not show the workings of his heart—what various Democrats described as the object of their inquiries. Practiced, garrulous, tedious, combative, and smugly civil, the judge repeated stock answers that deflected from his constitutional philosophy and his more controversial court decisions, such as those that favored corporations or the religious liberty of non-church entities . “I am a judge, I am my own man,” Gorsuch repeated, enforcing Republicans’ collective and transparent theme: When one dons the robe, their personal opinions, religious or otherwise, are irrelevant.

Despite claims of objectivity—“My job is to apply the laws you write,” he told lawmakers—the type of justice that Gorsuch will be is not a complete mystery. His philosophy is apparent in the cases he has decided. And, on matters of life and death, his philosophy is also evident in his book , The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia , published by Princeton University Press in 2006.

Life issues, especially abortion, likely pushed many religious conservatives to vote for Trump, because they wanted to secure an anti-abortion justice to fill the seat vacated after Antonin Scalia’s death. Senators repeatedly questioned Gorsuch about his views on abortion during his hearings—he revealed little—and some Democrats cited his rulings affecting women’s health as reasons to block his nomination. Senate Democrats ultimately did block Gorsuch, but Republicans were able to carry forward his confirmation anyway, changing the rules of the Senate in a historic vote to do so. As the dust from the contentious confirmation settles, it’s worth noting that Gorsuch’s nomination, in some ways, owes its provenance to the anti-abortion movement, making his own bioethical views all the more worth revisiting.

The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia is a resounding rebuke of the legalization of aid in dying (the term preferred by proponents, just coming into use at the time Gorsuch was doing his research). The book is not specifically about abortion, and the term is not even listed in the book’s index. Still, social conservatives have long defined their “pro-life” ethic as a “seamless garment,” covering a person’s life from birth through death. In this “consistent life” philosophy, abortion and stem cell research, as well as euthanasia and assisted suicide, are of a whole cloth—one is only defensible so much as the others are. “Once we open the door to excusing or justifying the intentional taking of life as ‘necessary,’ we introduce the real possibility that the lives of some persons (very possibly the weakest and most vulnerable among us) may be deemed less ‘valuable,’ and receive less protection from the law, than others,” Gorsuch writes in the book, using language long employed in the anti-abortion wars (and frequently quoted by the media since his nomination).

Gorsuch has never ruled on an abortion case. In the book, he dispassionately references the arguments in Roe v. Wade that legalized abortion. Yet, Gorsuch uses “consistent life” language throughout the book—Chapter 10 outlines a “consistent end of life ethic”—in a way that has reassured anti-abortion groups . “All human beings are intrinsically valuable and the intentional taking of human life by private persons is always wrong,” Gorsuch writes early in the book. (The caveat, “by private persons,” leaves room for the death penalty, a “consistent life ethic” frequently left out by conservatives.)

The book began as Gorsuch’s doctoral dissertation while he was a student at Oxford University. (The text has recently come under fire for allegedly lifting passages from other sources without proper citation.) John Finnis, a conservative Catholic professor and well known natural law theorist , was Gorsuch’s dissertation advisor. Natural law grew out of the teachings of the thirteenth-century Catholic priest and Dominican friar Thomas Aquinas, who wrote that it meant “nothing else than the rational creature’s participation in the eternal law,” the law of God. Gorsuch grew up Catholic and attended a Jesuit high school, though he now attends an Episcopal church. His book, now more than a decade old, bears many of Finnis’s natural law influences.

Natural law’s definitions are contested today, but it has been famously claimed by other leaders in the judiciary and legislature, notably Justice Clarence Thomas . Natural law has become controversial, as proponents—including Finnis—have employed it to argue against same-sex relationships and abortion.

The first half of Gorsuch’s The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia is more small “c” catholic than large “C,” however. He eschews explicitly Catholic or religious arguments in favor of jurisprudence. He outlines four arguments that are derived from judicial decisions in two prominent 1997 cases: Washington v. Glucksberg and Quill v. Vacco , both of which dealt with the constitutionality of aid in dying. In the first case, Harold Glucksberg and three other doctors challenged Washington state’s 1997 Natural Death Act in order to show that prescribing a lethal dose of medication to a terminal patient was constitutional according to the 14th Amendment. The case won in district court but was ultimately denied by the Supreme Court.

In the second case, Timothy Quill, also a physician, challenged New York’s ban against aid in dying. Quill’s efforts regarding aid in dying were well known ; in 1991 he had written a landmark article for the New England Journal of Medicine in which he described prescribing barbiturates to a patient who was dying of leukemia. Although the prescription was ostensibly for Trumbull’s inability to sleep, her desire to hasten her death was understood by Quill. He was never charged for a crime.

Like Glucksberg , Quill also failed in the courts. The United States Supreme Court, in a 9-0 decision, ruled that aid in dying was not guaranteed under the Constitution. Although unanimous, the decision resulted in six different judicial opinions, leaving open various interpretations for future discussion.

The first question that Gorsuch examines in The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia deals with judges’ concerns that historical precedent prevents aid in dying from being constitutional. Those seeking aid in dying were reacting to new medical technologies—advanced cancer therapies, new techniques of “life” or physiological support—that prolonged death (and patients’ pain) and had not been considered before by law. Jill Lepore writes at The New Yorker that Gorsuch “has his doubts about the history test,” which he outlines in the book’s “The Debate Over History” chapter. This stance is a slight diversion from Scalia, who Lepore writes “spent much of his career arguing for the importance of history in the interpretation of the law.”

The second question under Gorsuch’s consideration regards fairness and equal protection. How can aid in dying be provided to only some, say the terminally ill, and not others, like the mentally ill? Gorsuch discusses the challenges of determining patient consent when a patient is mentally incompetent or too young to make decisions for themselves. He draws a bright distinction between refusing medical treatment—which he argues should be legal—and seeking aid in dying. He argues that the intent of the prescribing doctor determines the legality of an action.

The third question Gorsuch asks is if the “due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment creates a constitutional guarantee of ‘self-sovereignty,’ embracing all ‘basic and intimate exercises of personal autonomy.’” Whether these “substantive rights”—the issues of “marriage, procreation, contraception, family relationships, childrearing, and education”—included aid in dying was disputed by the courts.

Yet, questions of autonomy and substantive rights are central to Planned Parenthood v. Casey , which reaffirmed the right to abortion, Gorsuch notes. He refrains from criticizing the Casey decision; he simply does not believe that the decision can fully be used to uphold legal aid in dying. He makes this argument, seeming to dismiss the portion of the Casey decision that would, according to many, include aid in dying:

These matters, involving the most intimate and personal choices a person may make in a lifetime, choices central to personal dignity and autonomy, are central to the liberty protected by the Fourteenth Amendment. At the heart of the liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.

To elucidate autonomy, Gorsuch points us to Cruzan v. Director, Missouri Department of Health , cited in various rulings of both Glucksberg and Quill , which determined that patients had the right to end or remove medical treatment because of the “common-law rule that forced medication was a battery,” as Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote. Does that right extend to aid in dying, Gorsuch asks, or is aid in dying part of one’s “lifestyle choices,” a phrase long used to shame and disparage legal abortion. Of course, in jurisprudence, abortion and aid in dying legislation have always been intertwined: The question of when life begins—and what its value is—is innate to the question of when life ends. As Richard Doerflinger, the Associate Director of Pro-Life Activities at the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, once told me , one’s life “isn’t one’s own.”

Gorsuch’s final question in the first half of the book examines whether “society as a whole would be improved or worsened” by legalization of assisted suicide, citing fears that the mentally ill, the disabled, or elders would be coerced into ending their lives prematurely. At the time that Gorsuch’s book was published, these fears were already being refuted by the data coming out of Oregon, where aid in dying had been legal for nearly a decade . Critics had claimed that the state’s law would lead to elder abuse, coercion of patients, or a “slippery slope” where patients who were not terminally ill or mentally capable of making their own medical decisions would be harmed. In 2006, the year that Gorsuch’s book was released, sixty-five people received lethal medication via the law; forty-six used it to end their lives. There were no reports of abuse.

Today, nearly 20 years after Oregon’s law went into effect, such fears remain unfounded . In 2015, 218 patients in Oregon received a prescription to aid in dying, but only 132 used it. According to the Oregon health department, most of those patients were enrolled in hospice (where they had access to pain relief), and they died at home—the place where a majority of Americans in surveys say they wish to die.

Washington state passed the Death with Dignity Act, which was modeled on Oregon’s law, in 2008. Four more states have since followed: Montana (2009); Vermont (2013); California and Colorado (2016). At any given time, at least a dozen states have active bills to legalize aid in dying. Gorsuch’s predictions were in part true: The Oregon “experiment” set the stage for other states to adopt aid in dying laws, but his recommendations for the judiciary on how to counter the movement’s progress—protecting a traditionally conservative definition of “the “inviolabillty,” or sanctity, of life—have often proven unsuccessful or unheeded.

The language of much of Gorsuch’s book is dated and jarring to those who have worked for end-of-life rights for decades. Gorsuch consistently uses “killing” or “committing suicide” for aid in dying. In reality, the underlying disease is the killer. As desperate terminal patients have long countered, they are not suicidal and their killer is their illness—not a prescribing doctor or a lethal medication. Death, regardless of the means, is guaranteed. This fact makes their decision not about how they die (although medication is the least traumatic means possible) or when they die (each person is free, according to the laws, to decide the time of ingestion), but about the most important, most present question of their every minute: how much pain they can bear.

While researching my own book on end-of-life care in the U.S., I found it impossible to deny the physical and emotional pain of dying patients who sought a way to live—they desperately wanted to live—their last weeks and days without pain. Robert Baxter, who brought the case that made aid in dying legal in Montana, was not suicidal. He no more wanted to kill himself than you or me. But he knew that his death was inevitable. In his affidavit to the court, Baxter wrote that he could only avoid impossible suffering by being fully sedated. “My family would be forced to stand a horrible vigil while my unconscious body was maintained in this condition, wasting away … while they waited for me to die.”

The Montana State Supreme Court ultimately ruled that Baxter had a right to receive lethal medication, but it was too late. He had already died. Perhaps it is a lack of knowledge about how these patients suffer that allows legal theorists like Gorsuch to claim lofty ideals about the quality and inviolability of life. Otherwise, the denial of the inherent protections and compassion of the law, indeed, of the ability of aid in dying laws to provide compassion in the face of this suffering, seems coldly cruel and the most damning aspect of this book.

Ann Neumann is author of The Good Death: An Exploration of Dying in America and a visiting scholar at the Center for Religion and Media at New York University where she writes the column, “The Patient Body,” for The Revealer . She has written for The New York Times , The Baffler , Harvard Divinity Bulletin , and Guernica magazine, where she is a contributing editor.

R&P Newsletter

Sign up to receive our newsletter and occasional announcements.

- Asia - Pacific

- Middle East - Africa

- Apologetics

- Benedict XVI

- Catholic Links

- Church Fathers

- Life & Family

- Liturgical Calendar

- Pope Francis

- CNA Newsletter

- Editors Service About Us Advertise Privacy

Gorsuch made an important distinction when asked about assisted suicide

By Matt Hadro

Washington D.C., Mar 22, 2017 / 15:11 pm

Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch made a crucial ethical distinction in his response to questions about doctor-prescribed suicide during his confirmation hearing on Wednesday, said one ethicist.

When asked what his views were on end-of-life care in the case of a terminal patient enduring unbearable pain, Gorsuch replied that "anything necessary to alleviate pain would be appropriate and acceptable, even if it caused death. Not intentionally, but knowingly. I drew the line between intent and knowingly."

This is an important distinction, said Edward Furton Ph.D., director of publications and an ethicist at the National Catholic Bioethics Center. He told CNA that the situation presents the case of "double-effect," where proper steps taken to alleviate a patient's pain may have the side effect of causing their death, but are permissible when certain conditions are met.

"You've got a good intention, the action you're doing is good – in this case, it's alleviating the pain with appropriate amounts of medication," he explained, emphasizing that the dosage of pain medication may never be lethal and should not render the patient unconscious except when "absolutely necessary."

"You've got a side effect, which is not intended, but is foreseen. It is going to happen, but you don't want it to happen, you're doing your action for another reason. And there is really no other route to alleviate the pain. So this is perfectly appropriate, it makes good sense," Furton said.

Gorsuch, a judge on the Tenth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, faced his third day of questioning before the Senate Judiciary Committee on Wednesday as he is considered for confirmation to replace the late Justice Antonin Scalia on the Supreme Court.

He wrote a book in 2006 on "The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia." Gorsuch explored various arguments made in favor of doctor-prescribed suicide and euthanasia before offering his own observations and opinions.

The book "was my doctoral dissertation, essentially," he told the Senate Judiciary Committee on Wednesday. It was written "in my capacity as a commentator" and not as a judge, he clarified. The book was published the same year he was nominated and confirmed to the Tenth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

He argued in the book that "human life is fundamentally and inherently valuable, and that the intentional taking of human life by private persons is always wrong." Regarding doctor-prescribed suicide, he upheld laws prohibiting it, basing his argument upon "secular moral theory."

Senate advances bills to protect privacy and safety of children online

Asked by Sen. John Kennedy (R-La.) to briefly discuss his book, Gorsuch suggested that doctor-prescribed suicide could pose a significant threat "to the least amongst us – the vulnerable, the elderly, the disabled."

It does this by becoming a cheap end-of-life option offered to vulnerable people, he said. "I do know that when you have a more expensive option and a cheaper option, those who can't afford the more expensive option tend to get thrust into the cheaper option."

"It's a long book. It's complicated. And I do not profess to have the right, final, or complete answer," he admitted. "I hoped, at most, to contribute to a discussion on an unanswered social question where all people – and I do think all people – have a good faith interest in trying to reach some consensus socially on it."

Currently, doctor-prescribed suicide is legal in six states and in the District of Columbia, with some 25 states to consider legalizing it this year.

Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) pressed Gorsuch on the matter on Wednesday, citing California's End of Life Option Act that legalized the procedure in the state.

"I, in my life, have seen people die horrible deaths – family, of cancer – when there was no hope. And my father, begging me, 'stop this Diane, I'm dying'," she explained. "And my father was a professor of surgery."

"And the suffering becomes so pronounced – I just went through this with a close friend – that this is real. And it's very hard," she continued, asking him what he thought of California's law.

(Story continues below)

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

Gorsuch, speaking in his personal capacity, said that for some terminal patients, "at some point, you want to be left alone. Enough with the poking and the prodding. 'I want to go home and die in my own bed in the arms of my family'."

"And the Supreme Court recognized in Cruzan" – a 1990 decision on an end-of-life case – "that that's a right in common law, to be free from assault and battery, effectively. And assumed that there was a Constitutional dimension to that. I agree."

Gorsuch added that the matter of a terminal, suffering patient foregoing treatment was a personal one for him.

"Your father, we've all been through it with family. My heart goes out to you. It does. And I've been there with my dad. And others," he told Feinstein.

Speaking as an ethicist, Furton clarified that in end-of-life cases, pain management may certainly be used but should never be an overdose and should not render the patient unconscious except in extraordinary circumstances.

Pain medication should be "measured, so that it matches the pain that the patient is experiencing," he said.

"You can't just give them a massive dose, or something like that," he said, as "it would bring about their death in a way that was not measured and not connected to a proper intention which is to alleviate the pain."

And medication should not induce unconsciousness, except in extraordinary cases, he insisted.

"Another important element is that the loss of consciousness in a person who is dying is very significant, and shouldn't happen unless it's absolutely necessary, because we should meet our Maker alert and in a prayerful way," he added.

Furton praised Gorsuch's knowledge and treatment of the matter as someone who "has obviously thought about these issues very carefully."

"So I think we should be happy that he has such a strong sense of where to draw the line in a case such as this, where you've got a person with intractable pain and needs to have it remedied," Furton said.

"He understands that that is not intentionally killing somebody. It's not euthanasia, it's not physician-assisted suicide. A lot of people don't understand the difference between those two, so it's good that he does because he's obviously going to be a man of considerable power and importance in the area of law."

- Catholic News ,

- Assisted Suicide ,

- Neil Gorsuch ,

- Supreme Court of the United States

Our mission is the truth. Join us!

Your monthly donation will help our team continue reporting the truth, with fairness, integrity, and fidelity to Jesus Christ and his Church.

I read Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch's book. It's very revealing.

by Dylan Matthews

Neil Gorsuch has not publicly stated whether or not he thinks Roe v. Wade was correctly decided. But if you read his one published book, The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia , his position on right-to-life issues becomes exceptionally clear, and it’s not particularly difficult to infer what they imply for his thinking on abortion.

Gorsuch’s core argument in the book is that the US should “retain existing law [banning assisted suicide and euthanasia] on the basis that human life is fundamentally and inherently valuable, and that the intentional taking of human life by private persons is always wrong.” The “private persons” bit there is telling — Gorsuch elaborates, “I do not seek to address publicly authorized forms of killing like capital punishment and war.”

Nor does his argument explicitly address abortion. But many of the book’s arguments apply equally well to both euthanasia and abortion — the latter of which could be considered the intentional taking of human life by private persons by a judge inclined to enact Gorsuch’s principle.

And make no mistake: Gorsuch sees this argument as having legal implications, beyond merely moral ones. At the end of the book, he advances an argument that laws allowing assisted suicide could be unconstitutional on equal protection grounds, and argues that the Equal Protection Clause could be interpreted as including his “inviolability-of-life principle.” If applied to abortion, that argument could easily be used to contend that not only is abortion not constitutionally protected, but that the Constitution actually requires laws banning abortion.

To be clear, Gorsuch never explicitly states that he thinks this argument should be used that way. But for reproductive rights supporters, the argument should raise many red flags nonetheless.

Gorsuch thinks the “inviolability of life” could be in the Constitution

Most of the book focuses not on the law per se, but on moral arguments. It grew out of a doctoral dissertation Gorsuch wrote at Oxford, where he studied as a Marshall scholar. His adviser was John Finnis, a hugely influential conservative Catholic legal philosopher who is a prominent defender of a “natural law” approach to jurisprudence. Finnis’s work attempts to provide a rigorous, secular philosophical justification for the approach to ethics and law that follows from Catholic social teaching. Gorsuch isn’t a Catholic (he belongs to a quite liberal Episcopal congregation ), but his book makes clear he shares Finnis’s view that the law and morality are not easily extricable.

At the end of the book, after many chapters arguing for his view that human life can never be taken by private actors and arguing against assisted-suicide supporters like Ronald Dworkin and Peter Singer, Gorsuch provides an intriguing argument for why this moral stance of his could have legal significance.

“The inviolability-of-life principle is strongly associated with the concept of human equality; the two are mutually reinforcing ideas,” he writes. That invites the possibility of a challenge to laws allowing assisted suicide on the grounds that they discriminate against the disabled, or the terminally ill, by making their lives subject to termination by medical professionals acting in “good faith” without those professional facing any legal punishment.

Gorsuch strongly implies he thinks a challenge on these lines could, and should, succeed. He contends that when a law involves a marginalized group like disabled people, that demands more stringent review, perhaps including review under intermediate or strict scrutiny, legal standards that require laws serve a compelling government interest if they’re to be found constitutional.

This argument jibes strongly with disability rights activists ’ arguments against assisted suicide , which focus on the potential for abuse, the potential for family members and doctors to pressure disabled people to kill themselves contrary to their own wishes, and for cases of depression to lead to euthanasia because the depressed party happens to also have a physical disability. Most disability rights activists view assisted-suicide laws as dangerous invitations to discrimination against disabled people.

But one line in the book indicates the equal protection argument could extend further, and apply not only to euthanasia but also to abortion. “Any line one might draw among human beings for purposes of determining who must live and who may die ultimately seems to devolve into an arbitrary exercise of picking out which particular instrumental capacities one especially likes,” Gorsuch writes.

The problem here is that most lines one could devise beyond which abortion is banned and before which it is permitted are based, in some sense, on a fetus’s capacities: its potential to survive outside the womb, its ability to feel pain or formulate desires, etc. Birth is an exception; if you believe in an autonomy-based right of women to have abortions in all circumstances, then you need not worry about the capacities of the fetus. But the Supreme Court has made distinctions in the past based on the trimester of pregnancy, or whether the fetus is “viable” outside the mother. Gorsuch suggests that capacity-based distinctions like this might be illegitimate.

That could have huge implications for his abortion jurisprudence. For one thing, if you take this line of argumentation all the way, then you could argue that state laws discriminating between fetuses on the basis of their capacities violate equal protection. That would imply that not only is there not a right to abortion, but states do not even have the right to allow it; fetuses have a constitutional right to live.

To be clear, Gorsuch has said nothing like this. His specific views on abortion remain unarticulated. But his line of reasoning opens the door to this conclusion in a provocative way.

Gorsuch presents euthanasia advocates as heirs to a toxic history

One of the most revealing sections of book as to Gorsuch’s overall attitude is chapter three, a historical overview of Western thought on suicide and euthanasia. The point is to provide some clue as to whether a right to die is deeply rooted in tradition and American history — a matter with serious legal significance.

Under a doctrine known as “substantive due process,” the Supreme Court has over the past century interpreted the 14th Amendment to not just guarantee that legal proceedings be carried out fairly but also protect certain fundamental freedoms from excessive regulation by the state. That’s the basis upon which the Court has determined that the Constitution protects the right to contraception , to abortion , to consensual sex , and to same-sex marriage .

Determining just what freedoms are protected is a matter of strong methodological dispute, but a widely held position among many jurists is that to be protected by substantive due process, a liberty or freedom has to be deeply rooted in tradition or American history. That can lead to somewhat awkward places. In 1972, the Court struck down a Massachusetts law banning the distribution of contraceptives to unmarried people, despite the fact that in many states bans like that were themselves a longstanding tradition, which would seem to run against the idea that the right to contraceptives outside of marriage had a strong historical basis.

Gorsuch himself seems to be very skeptical of using history to defend substantive due process claims, noting that in the contraceptive case, the “result can be defended fully, without contortions over historical ‘levels’ and even without reference to due process doctrine, as an equal protection decision simply and quite straightforwardly requiring the same access to contraceptives for married and unmarried persons alike.” This, tellingly, gives the same result but doesn’t provide much basis for thinking that both married and unmarried people have a right to contraception.

With that context laid out, Gorsuch proceeds to sketch out the attitudes toward suicide displayed by everyone from Plato to Aristotle to Roman law to St. Augustine to St. Thomas Aquinas to English common law and the practices of the American colonies. But he really gets going when it comes to the embrace of euthanasia by the late 19th/early 20th century eugenics movement, which viewed the practice as a way to, often involuntarily, prevent the proliferation of “feeble-minded” people in society.

Gorsuch goes to great lengths to demonstrate just how mainstream the view that doctors should kill disabled people was:

Clarence Darrow of Scopes Monkey fame proclaimed, “Chloroform unfit children. Show them the same mercy that is shown beasts that are no longer fit to live.” Novelist Sherwood Anderson and physician Abraham Wolbarst, two future members of the Euthanasia Society of America, openly argued that society had a duty to kill those with defects because they unnecessarily drained community resources. Madison Grant, a New York attorney and Yale Law graduate who also served as a trustee of the American Museum of Natural History and cofounded the American Eugenics Society, proclaimed that “[t]he laws of nature require the obliteration of the unfit and [a] human is valuable only when it is of use to the community or race.”… In 1939 Ann Mitchell, an ESA cofounder, welcomed the advent of World War II as a “biological house cleaning.” She counseled “euthanasia as a war measure, including euthanasia for the insane, feeble-minded monstrosities.”

Of course, euthanasia did become a war measure, specifically for Nazi Germany , which launched the T4 program the same month it invaded Poland; about 200,000 disabled people were killed in various Nazi euthanasia efforts. And the effort was substantially inspired by American euthanasia advocates. Gorsuch notes that Adolf Hitler himself wrote to Madison Grant, describing Grant’s pro-eugenics book Passing of the Great Race as “his Bible,” and stated that he had “studied with interest the laws of several American states concerning prevention of reproduction by people whose progeny would, in all probability, be of no value or be injurious to the racial stock.”

Understandably, association with Nazi atrocities destroyed the reputation of eugenics, and by extension euthanasia, in the United States. But within a few decades, arguments for euthanasia began gaining currency as a way to enhance the autonomy and ease the suffering of people at the end of their lives, quite apart from eugenic considerations. Most contemporary advocates explicitly and strenuously reject that legacy and argue that legalizing euthanasia and assisted suicide has nothing whatsoever to do with involuntary killings of the disabled.

While Gorsuch certainly doesn’t equate today’s euthanasia advocates with eugenicists, he does argue quite persistently that the differences are often slight, and that contemporary bioethicists supporting euthanasia from the 1960s and onward have been far too comfortable with killing people who do not themselves agree to be killed:

Joseph Fletcher, father of situational ethics, an Episcopal priest, and author of Morals and Medicine (1979), spent much of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s arguing for the movement’s “original task as the [Euthanasia Society of America] perceived it.” Fletcher called upon the euthanasia movement not only to press for assisted suicide and voluntary euthanasia, but also to advocate euthanasia for “helpless newborns or minors still too young to make any input into decisions about when to stop life-prolonging treatment.” Lie earlier ESA members, Olive Ruth Russell, psychologist and author of Freedom to Die: Moral and Legal Aspects of Euthanasia (1975), sought to extend legal euthanasia to infants with birth defects. Hearkening back to the Malthusian concerns of the social Darwinists, Russell viewed euthanasia as a means of combating the “surging rise in the number of physically and mentally crippled children.”

From here, Gorsuch glides seamlessly into citing passages from prominent ethicists like Dworkin or Singer that seem to endorse involuntary euthanasia. Dworkin, for instance, wrote that respecting individual autonomy means honoring a woman’s request to be killed should Alzheimer’s-induced dementia set in, even if once that happens the woman no longer wants to die. Singer, perhaps the most notorious of any euthanasia proponent, has argued for the justifiability of early infanticide, particularly in the case of disabled children, drawing the fierce opposition of disability rights advocates .

“Many of the policies they proffer would embrace not just a right to die, but a duty of certain persons to do so — and do so in some cases regardless of whether they consent,“ Gorsuch writes. He argues that it’s “hard to disagree” with the conclusion of the historian Ian Dowbiggin, who wrote that “today’s defenders of the right to die often echo the justifications of euthanasia first uttered” by eugenicists.

This obviously gives one a very strong sense of how Gorsuch would rule on end-of-life cases brought before the Court. But it also suggests something about his attitude toward abortion. Some early abortion advocates in the US were — as pro-life activists today are extremely eager to point out — also proponents of eugenics, with Planned Parenthood founder Margaret Sanger being perhaps the most famous example. By tying euthanasia to eugenics, Gorsuch is implicitly tying abortion to eugenics as well.

And within the world of contemporary moral philosophy, the defense of abortion is inextricably linked with the defense of assisted suicide and euthanasia. Dworkin laid out a comprehensive theory covering both in Life’s Dominion: An Argument About Abortion, Euthanasia, and Individual Freedom , arguing that only a particular view about how to respect the sanctity of human life can justify bans on the practices, and that it is illegitimate for the state to privilege one such view over others.

Singer’s defense of abortion and his defense of euthanasia of infants derive from identical premises: that neither fetuses nor infants are beings capable of wanting to continue living, so they have no preferences in that regard that other people are obligated to honor. Judith Jarvis Thomson, whose “A Defense of Abortion” is perhaps the single most influential philosophical article on the subject, has defended assisted suicide on similar, personal autonomy–based grounds.

Given that he paints arguments like these as heirs to the ideas that literally produced Nazi war crimes , it’s not hard to guess what Gorsuch thinks about their application to abortion.

Gorsuch is sympathetic to a limited view of due process

The most explicit the book gets on the topic of abortion is its analysis of Planned Parenthood v. Casey , the landmark 1992 case in which the Supreme Court upheld Roe v. Wade but allowed certain restrictions on abortion nonetheless. Casey is relevant to the debate over euthanasia because of its comments on how the Court should determine which rights are guaranteed by substantive due process and which are not.

While Gorsuch never plainly states his own views on substantive due process, he lays out those of Justices Hugo Black, Antonin Scalia, and Clarence Thomas at some length, and very sympathetically. Black is identified with the idea that the due process clause of the 14th amendment applied the Bill of Rights to the states. Previously, the first 10 amendments were thought only to apply to the federal government. Congress could make no law abridging the freedom of speech, but state legislatures could. Black thought that by guaranteeing all people due process of the law, the 14th Amendment “incorporated” the Bill of Rights and applied it to states.

But he also thought that substantive due process could go no further than that. It could not contain a right to privacy, to sexual freedom, to abortion or marriage or (certainly) assisted suicide. While Scalia accepted a broader view of substantive due process early in his tenure, he later flipped and declared that he could no longer “accept the proposition that [due process] is the secret repository of all sorts of other unenumerated, substantive rights.”

Gorsuch’s sympathetic recounting of this argument is not a conclusive indication of his own views. For one thing, Gorsuch notes that even if you take this view, you could think Roe v. Wade is correctly decided on other (for instance, equal protection ) grounds. But it is revealing, and suggests he’s at least sympathetic with the side of the Court that has voted to overturn Roe and other substantive due process–based rulings. It also suggests a limit to his conservatism. In the early 20th century, substantive due process was used to argue for “freedom of contract,” which led the Supreme Court in cases like Lochner v. New York to strike down limits on working hours, minimum wage laws, and other economic regulations. This view has been revived in conservative legal circles in recent years , but Gorsuch’s take on substantive due process suggests he doesn’t think the Constitution mandates libertarian economic policy.

Gorsuch’s comments on Casey bolsters this interpretation of his views. In the Casey opinion, Justices Sandra Day O’Connor, Anthony Kennedy, and David Souter argued, “At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.” If that test, meant to provide a more stable basis than reliance on history, is binding precedent, it could form the basis of a right to assisted suicide, which reflects a particular view on the part of the dying person of the meaning of their life.

But Gorsuch argues that it cannot be binding. For one thing, it’s not necessary for the result of Casey , which can be justified on the grounds of stare decisis — the Court was merely upholding its prior ruling in Roe , out of respect to settled law. For another, Gorsuch argues the test might “prove too much”: “If the Constitution protects as fundamental liberty interests any ‘intimate’ or ‘personal’ decisions, the Court arguably would have to support future autonomy-based constitutional challenges to laws banning any private consensual act of significance to the participants in defining their ‘own concept of existence.’” That opens the door to legalizing drugs, polygamy, dueling, prostitution, and various other activities. A lot of people might be willing to bite that bullet, but Gorsuch appears not to.

That dismissal of Casey’ s broad approach to substantive due process again suggests that Gorsuch shares Scalia and Thomas’s view: that the Constitution protects the liberties enumerated in the Bill of Rights, but not additional ones like a right to abortion.

More in this stream

40 years ago today, one man saved us from world-ending nuclear war

How gun ownership became a powerful political identity

Why scientists are cloning black-footed ferrets

Most popular, the misleading controversy over an olympic women’s boxing match, briefly explained, why two astronauts are stuck in space, 3 unexpected winners — and 1 predictable loser — from the paris olympics so far, intel was once a silicon valley leader. how did it fall so far, take a mental break with the newest vox crossword, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in Politics

An influencer is running for Senate. Is she just the first of many?

Israel’s January 6 moment

Legendary activist Kimberlé Crenshaw on why those white people Zooms give her hope

Chuck Schumer’s ambitious plan to take the Supreme Court down a peg

The Trump-Vance campaign would be great if not for Trump and Vance

The US-Russia prisoner swap that freed Evan Gershkovich, explained

Caroline Gleich’s Utah Senate campaign is a sign of the blurring lines between digital creators and politicians.

A far-right riot at a military base exposed the contradiction tearing Israel apart.

The scholar who coined “intersectionality” explains why those fundraisers from white Harris supporters really do matter.

Schumer wants to engage in jurisdiction stripping, a rarely used tactic that can shrink the Supreme Court’s authority.

The Trump team’s newfound professionalism can’t conceal their candidate’s longstanding flaws.

It’s the largest exchange since the Cold War.

Can men’s gymnastics be saved? Audio

Is the United States in self-destruct mode? Audio

The misleading controversy over an Olympic women’s boxing match, briefly explained

MDMA is on the brink of becoming medicine Audio

J.K. Rowling’s transphobia: A history

- Student Opportunities

About Hoover

Located on the campus of Stanford University and in Washington, DC, the Hoover Institution is the nation’s preeminent research center dedicated to generating policy ideas that promote economic prosperity, national security, and democratic governance.

- The Hoover Story

- Hoover Timeline & History

- Mission Statement

- Vision of the Institution Today

- Key Focus Areas

- About our Fellows

- Research Programs

- Annual Reports

- Hoover in DC

- Fellowship Opportunities

- Visit Hoover

- David and Joan Traitel Building & Rental Information

- Newsletter Subscriptions

- Connect With Us

Hoover scholars form the Institution’s core and create breakthrough ideas aligned with our mission and ideals. What sets Hoover apart from all other policy organizations is its status as a center of scholarly excellence, its locus as a forum of scholarly discussion of public policy, and its ability to bring the conclusions of this scholarship to a public audience.

- Peter Berkowitz

- Ross Levine

- Michael McFaul

- Timothy Garton Ash

- China's Global Sharp Power Project

- Economic Policy Group

- History Working Group

- Hoover Education Success Initiative

- National Security Task Force

- National Security, Technology & Law Working Group

- Middle East and the Islamic World Working Group

- Military History/Contemporary Conflict Working Group

- Renewing Indigenous Economies Project

- State & Local Governance

- Strengthening US-India Relations

- Technology, Economics, and Governance Working Group

- Taiwan in the Indo-Pacific Region

Books by Hoover Fellows

Economics Working Papers

Hoover Education Success Initiative | The Papers

- Hoover Fellows Program

- National Fellows Program

- Student Fellowship Program

- Veteran Fellowship Program

- Congressional Fellowship Program

- Media Fellowship Program

- Silas Palmer Fellowship

- Economic Fellowship Program

Throughout our over one-hundred-year history, our work has directly led to policies that have produced greater freedom, democracy, and opportunity in the United States and the world.

- Determining America’s Role in the World

- Answering Challenges to Advanced Economies

- Empowering State and Local Governance

- Revitalizing History

- Confronting and Competing with China

- Revitalizing American Institutions

- Reforming K-12 Education

- Understanding Public Opinion

- Understanding the Effects of Technology on Economics and Governance

- Energy & Environment

- Health Care

- Immigration

- International Affairs

- Key Countries / Regions

- Law & Policy

- Politics & Public Opinion

- Science & Technology

- Security & Defense

- State & Local

- Books by Fellows

- Published Works by Fellows

- Working Papers

- Congressional Testimony

- Hoover Press

- PERIODICALS

- The Caravan

- China's Global Sharp Power

- Economic Policy

- History Lab

- Hoover Education

- Global Policy & Strategy

- Middle East and the Islamic World

- Military History & Contemporary Conflict

- Renewing Indigenous Economies

- State and Local Governance

- Technology, Economics, and Governance

Hoover scholars offer analysis of current policy challenges and provide solutions on how America can advance freedom, peace, and prosperity.

- China Global Sharp Power Weekly Alert

- Email newsletters

- Hoover Daily Report

- Subscription to Email Alerts

- Periodicals

- California on Your Mind

- Defining Ideas

- Hoover Digest

- Video Series

- Uncommon Knowledge

- Battlegrounds

- GoodFellows

- Hoover Events

- Capital Conversations

- Hoover Book Club

- AUDIO PODCASTS

- Matters of Policy & Politics

- Economics, Applied

- Free Speech Unmuted

- Secrets of Statecraft

- Capitalism and Freedom in the 21st Century

- Libertarian

- Library & Archives

Support Hoover

Learn more about joining the community of supporters and scholars working together to advance Hoover’s mission and values.

What is MyHoover?

MyHoover delivers a personalized experience at Hoover.org . In a few easy steps, create an account and receive the most recent analysis from Hoover fellows tailored to your specific policy interests.

Watch this video for an overview of MyHoover.

Log In to MyHoover

Forgot Password

Don't have an account? Sign up

Have questions? Contact us

- Support the Mission of the Hoover Institution

- Subscribe to the Hoover Daily Report

- Follow Hoover on Social Media

Make a Gift

Your gift helps advance ideas that promote a free society.

- About Hoover Institution

- Meet Our Fellows

- Focus Areas

- Research Teams

- Library & Archives

Library & archives

Events, news & press.

Neil Gorsuch: An Eloquent Intellectual

The president’s nominee for the Supreme Court is a credit to his profession.

Within hours of the nomination of Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court of the United States, the battle lines had already formed. Leftwing groups were reflexively opposed—as they would oppose any Republican nominee. Right-leaning groups rallied in support. It became almost impossible to separate truth from falsehood, analysis from spin.

I served on the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals with Judge Gorsuch for over three years, before moving to Stanford University to teach constitutional law. He and I sat together on almost 50 cases of every description. We did not always agree. But Neil Gorsuch is a man of intelligence, independence, and integrity. In my opinion, he is a superb choice to replace Justice Antonin Scalia on the Court. In normal times, he would be swiftly and easily confirmed. Alas, these are not normal times.

Qualifications and Qualities of Mind

Gorsuch has impeccable and impressive qualifications for the High Court: a law degree from Harvard, a doctorate in legal philosophy from Oxford, Supreme Court clerkships with moderate Justices Byron White and Anthony Kennedy, private practice with one of the most respected law firms in Washington, public service at the Department of Justice, and now ten years of outstanding work on the Tenth Circuit. When nominated to that court in 2006, he won high praise from both sides of the aisle and was confirmed unanimously by the Senate.

More important than his qualifications are his qualities of mind. He is rigorously intelligent, fair-minded, and one of the finest writers in the entire judiciary. Like Justice Scalia, he tries to minimize the role that judges’ own views play in the interpretation of the law. Perhaps unlike Justice Scalia, a pugnacious lover of intellectual battle whose intellectual inclination was to clarify and sharpen differences, Gorsuch looks for common ground, even with judges of a generally opposing position. We see both of these qualities in this witty passage from Gorsuch’s dissenting opinion last year in A.M. v. Holmes :

Often enough the law can be “a ass—a idiot,” Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist 520 (Dodd, Mead & Co. 1941) (1838)—and there is little we judges can do about it, for it is (or should be) emphatically our job to apply, not rewrite, the law enacted by the people’s representatives. Indeed, a judge who likes every result he reaches is very likely a bad judge, reaching for results he prefers rather than those the law compels. So it is I admire my colleagues today, for no doubt they reach a result they dislike but believe the law demands—and in that I see the best of our profession and much to admire. It’s only that, in this particular case, I don’t believe the law happens to be quite as much of a ass as they do. I respectfully dissent.

I asked my research assistant to pull every case in the last five years where Judge Gorsuch sat with both a Republican-appointed and a Democratic-appointed judge and the panel split as to the outcome. The results were striking. In almost a third of the cases, Judge Gorsuch voted with his presumably more liberal Democratic colleagues rather than the presumably more conservative Republicans. That is the mark of an independent, non-partisan jurist.

This is not just my opinion. In the days since the nomination, several liberal professors have studied his record and come to a similar conclusion.

Principles of Interpretation

Judge Gorsuch is a longstanding proponent of the view that the Constitution must be interpreted according to its text as it was understood by those with authority to enact it. In his words: “Ours is the job of interpreting the Constitution. And that document isn’t some inkblot on which litigants may project their hopes and dreams for a new and perfected tort law, but a carefully drafted text judges are charged with applying according to its original public meaning.” ( Cordova v. City of Albuquerque (2016)). That sometimes leads to conservative results, but not always. As one liberal law professor wrote: “He is way too conservative for my taste, but his decisions are largely principled and fair from his originalist’s view of constitutional interpretation. . . . That approach can result in decisions that don’t reliably fall into any one place on the liberal-to-conservative spectrum.”

If the Constitution, fairly interpreted, does not speak to an issue, Judge Gorsuch leaves it to the political process. As he wrote in tribute to his mentor Justice Byron White, we should have “confidence in the people’s elected representatives, rather than the unelected judiciary, to experiment and solve society’s problems, so long as the procedures used were fair and the opportunity to participate was open to all.”

For example (and like Justice Scalia), this approach often leads him to rule in favor of criminal defendants based on the original meaning of constitutional trial guarantees or a narrow textual reading of criminal statutes. One example is United States v. Carloss (2016). In that case, he dissented from a decision holding that police may disregard a property owner’s “No Trespassing” signs. Gorsuch responded to the government’s concern that a contrary rulling would make the “job of ferreting out crime . . . marginally more difficult” with the pungent riposte: “[Obedience to the Fourth Amendment always bears that cost and surely brings with it other benefits. Neither, of course, is it our job to weigh those costs and benefits but to apply the Amendment according to its terms and in light of its historical meaning.” In many more cases, Judge Gorsuch has voted to affirm convictions. His overall record in criminal cases is neither pro-prosecution or pro-defendant, but simply obedient to the law.

There is no reason to think that Judge Gorsuch regards the death penalty as unconstitutional. Perhaps that is because it is not.

Judge Gorsuch’s approach has led him to defend the constitutional autonomy of the states – whether exercised by a conservative Republican governor in Planned Parenthood v. Herbert (2016) or a liberal Democratic governor in Kerr v. Hickenlooper (2014). In light of the recent revival of interest in local autonomy in progressive circles, these power-devolving doctrines may win newfound respect. The genius of our system is to empower conservative states like Texas or West Virginia to resist progressive presidencies, and liberal states like California or Washington to resist conservative ones.

Judge Gorsuch’s opinion for the court in Energy & Environment Legal Inst. v. Epel (2016) has received little attention from his progressive critics. In it, Judge Gorsuch rejected a highly plausible challenge by a corporation to Colorado’s renewable energy rules, based on his reading of the historical meaning of the Commerce Clause. The case was a three-fer: it was against a corporation, in favor of environmental laws, and based on originalist interpretation. No wonder progressives prefer to ignore it!

The same principles probably make Judge Gorsuch skeptical of the Supreme Court’s jurisprudence on same-sex marriage and abortion. But whatever his views may be, they will not affect the balance of votes on those issues. He is replacing Justice Scalia, after all. I personally believe that the issue of same-sex marriage will not be reopened, and that some 45 years of precedent make radical change on abortion unlikely, no matter who is on the Court or what they think of the legal reasoning in Roe v. Wade .

Most importantly, Judge Gorsuch has never had a case on abortion rights, same-sex marriage, gun rights, or affirmative action. Any worries or hopes on these issues are purely a matter of speculation. Judge Gorsuch did, however, dissent from a Tenth Circuit decision forbidding the governor of Utah from cutting the funding from Planned Parenthood. The legal issue was the imputation of an unconstitutional motive to the governor without actual evidence of it, which could arise in any number of political contexts. Nothing in his opinion suggests that the abortion context affected his analysis. Gorsuch also dissented from the conviction of a defendant charged with knowing possession of a firearm, on the ground that the government did not prove an element of the crime. This decision has, absurdly, been treated as evidence of pro-gun views. Judge Gorsuch’s dissenting opinion begins this way:

People sit in prison because our circuit's case law allows the government to put them there without proving a statutorily specified element of the charged crime. Today, this court votes narrowly, 6 to 4, against revisiting this state of affairs. So Mr. Games-Perez will remain behind bars, without the opportunity to present to a jury his argument that he committed no crime at all under the law of the land.

The language is passionate—but about innocence, not gun rights.

Freedoms of Speech and Religion

Among Judge Gorsuch’s most impassioned commitments is to the freedoms of speech and religion. Probably his best-known cases are Hobby Lobby v. Sibelius (2014), which upheld the right under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of a closely-held family corporation not to be compelled to pay for insurance coverage of what they sincerely believe to be abortion-inducing drugs, and Little Sisters of the Poor v. Burwell , which applied the same principles to a Catholic religious order. I suspect most Americans agree that Catholic nuns should not be forced to pay for things their religion condemns. In my opinion, a government attentive to civil liberties would never have tried. Hobby Lobby was affirmed by the Supreme Court, and Little Sisters of the Poor was remanded in the expectation that the government could accommodate the Sisters’ religious beliefs without sacrificing any compelling governmental interests.

Judge Gorsuch’s commitment to freedom of religion extends to all faith and all kinds of people: to prisoners, to Muslims, to Native Americans, as well as to Christians. In Yellowbear v. Lampert (2014), for example, he wrote an opinion supporting the claim of a Native American prisoner for access to a sweat lodge for religious ceremonials. In Abdulhaseeb v. Calbone (2010), he supported the claim of a Muslim prisoner to religiously appropriate food. On the other hand, he recognizes that not all claims of religious freedom are legally warranted. He voted to reject a claim by members of a so-called “Church of Cognizance” to use marijuana as a sacrament, and claims by atheist and secular groups to tear down public monuments with religious elements. In the latter, Judge Gorsuch’s indignant common sense comes through:

It is undisputed that the state actors here did not act with any religious purpose; there is no suggestion in this case that Utah's monuments establish a religion or coerce anyone to participate in any religious exercise; and the court does not even render a judgment that it thinks Utah's memorials actually endorse religion. . . . Thus it is that the court strikes down Utah's policy only because it is able to imagine a hypothetical "reasonable observer" who could think Utah means to endorse religion—even when it doesn't.

Two freedom of speech cases warrant mention. In Riddle v. Hickenlooper (2014), he concurred in a decision protecting the right of minor-party candidates and their supporters to make campaign contributions equal to those allowed the Republicans and Democrats. And in Van Deelen v. Johnson (2007), he voted to extend the protection of the Petition Clause of the First Amendment to statements made in a petition, even if those statements were on a private matter and were in fact baseless. Judge Gorsuch explained, “[T]he constitutionally numerated right of a private citizen to petition the government for the redress of grievances does not pick and choose its causes but extends to matters great and small, public and private.”

Executive Power

Tenth Circuit judges do not have many opportunities to rule on the scope of executive power, but arguably this will be the most prominent Supreme Court issue of the coming decade. Not only will there be high-profile contests involving the ever-controversial President Donald Trump, but there will be even more cases involving the ever-increasing authority of bureaucratic agencies to govern our lives without congressional say-so or real democratic accountability.

As it happens, Neil Gorsuch has addressed this question, albeit obliquely. An alien, Hugo Rosario Gutierrez-Brizuela, applied to the immigration authorities for a change in immigration status. The executive branch, however, had changed its mind about how to handle this class of aliens, and applied its new-found ideas retroactively to Mr. Gutierrez-Brizeula. The court rejected the government’s position for technical reasons. Judge Gorsuch filed a separate concurring opinion. Rather than characterize it, I will quote a passage from the opinion. I believe it tells us all we need to know about what kind of Justice my former colleague will be:

[T]he founders considered the separation of powers a vital guard against governmental encroachment on the people's liberties, including all those later enumerated in the Bill of Rights. What would happen, for example, if the political majorities who run the legislative and executive branches could decide cases and controversies over past facts? They might be tempted to bend existing laws, to reinterpret and apply them retroactively in novel ways and without advance notice. Effectively leaving parties who cannot alter their past conduct to the mercy of majoritarian politics and risking the possibility that unpopular groups might be singled out for this sort of mistreatment — and raising along the way, too, grave due process (fair notice) and equal protection problems. Conversely, what would happen if politically unresponsive and life-tenured judges were permitted to decide policy questions for the future or try to execute those policies? The very idea of self-government would soon be at risk of withering to the point of pointlessness. It was to avoid dangers like these, dangers the founders had studied and seen realized in their own time, that they pursued the separation of powers. A government of diffused powers, they knew, is a government less capable of invading the liberties of the people.

In times like these, we need judges who are neither toadies nor resisters. We need judges who take their bearings from the Constitution, and not from party loyalties. In Neil Gorsuch, we have such a judge.

Neil Gorsuch: The Man For The Court , by Richard A. Epstein

View the discussion thread.

Join the Hoover Institution’s community of supporters in ideas advancing freedom.

The Hastings Center

Bioethics Forum Essay

Neil gorsuch, aid in dying, and roe v. wade.

In the absence of any paper trail that would give clues to Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch’s views on abortion, many commentators have turned to his book, The Future of Assisted Suicide and Euthanasia , based on his doctoral dissertation at Oxford, where he worked with natural law theorist John Finnis. Ronald M. Green notes with alarm that Gorsuch relies on an inviolability-of-life principle that would likely lead him to vote to overturn Roe v. Wade . Furthermore, Green writes that Gorsuch’s conservative preference for allowing states to make their own decisions would lead to a return to the pre- Roe reality in which women would have to travel long distances for abortions in those states that allowed it.

However, there are more dire possibilities to consider. In a long and fascinating essay in Vox, J. Paul Kelleher argues that Gorsuch is not an originalist in the Scalia mold, but actually a natural law adherent like his mentor Finnis. Natural law theorists believe that there is an overarching moral law that judges can and must rely on when existing laws are unclear, or manifestly unjust. The recognition of human life as a “fundamental good” that can never be intentionally harmed, is an example of such a moral law, and one that Gorsuch relies on in his condemnation of assisted suicide.

It’s important to see that Gorsuch is not merely agreeing with the current legal status of assisted suicide in our country. In Washington v. Glucksberg , in 1997, the Supreme Court declined to follow the logic of the “privacy” cases stretching from contraception through abortion and find a constitutional right to assistance in ending one’s life. Glucksberg leaves the country, with respect to assisted suicide, in the same position in which we would be left with respect to abortion if Roe were overturned: at the mercy of the legislative wisdom of the individual states. Gorsuch goes further in arguing that the equal protection clause of the 14 th Amendment forbids treating the lives of terminally ill people differently from those of the healthy, by allowing the “killing” of the first but not the second (a view often argued by philosopher Felicia Nimüe Ackerman). In other words, Gorsuch would presumably view favorably an appeal to the Court to strike down existing “death with dignity” laws in Oregon and elsewhere.

As Corey Brettschneider writes in the New York Times , all of our abortion jurisprudence rests on the assumption that embryos and fetuses are not “constitutional persons” under the 14 th Amendment. Anti-abortion activists have made occasional gestures toward a constitutional amendment, declaring embryos to be constitutional persons from the moment of conception. But constitutional amendments are very hard to pass, as proponents of the Equal Rights Amendment will recall. Relying on natural law theory, John Finnis has written that fetuses deserve to be considered constitutional persons. Thus, an equal protection argument claiming that the 14 th Amendment requires embryos and fetuses to be treated the same as born children might acquire some traction with Gorsuch on the Court. The result would be much worse for abortion rights than simply overturning Roe ; it would criminalize abortion across the country.

Dena S. Davis, JD, PhD, Hastings Center Fellow, is the Endowed Presidential Chair in Health and a professor of bioethics and religion studies at Lehigh University. A version of this essay originally appeared on Bioethics and Other Stuff .

Hastings Bioethics Forum essays are the opinions of the authors, not of The Hastings Center.

All is not well where assisted suicide is legal. There is documented abuse see Thomas Middleton Fed case where he was killed via the OR policy for his assets. A public policy failure. I was my wife’s 24/7 caregiver during her last 18 months of declining autonomy. Pitfalls in assisted suicide laws need attention. We already have the right to refuse treatment. Many who believe in the concept under the choice banner have second-thoughts org she n they read the language of the actual bill and realize our choice is Ignored and certainly not assured. This is not about people who are dying anyway. Amending Colorado’s Prop 106 is sorely needed (and OR,WA,CA). The initiative a monopoly and profit center was bought for $8,000,000 of deception. Even as they proclaimed that the poison must be self administered they did not provide for an ordinary witness. The difference is that without a witness it allows forced euthanasia but with a witness they would up hold individual choice.

Amendments would include requiring a witness to the self administration, restore the illegality of falsifying the death certificate require the posting of the poison applied in the medical record for the sake of good stewardship for future studies, register organ/tissue trafficking, reveal commissions and memorials paid to the corporate facilitators and keep all records for transparent public safety policy. These Oregon model bills do not assure our choice and ignore our choice by empowering predatory corporations over us. Bradley Williams President MTaas org

- Pingback: Gavel Drop: A Flurry of Title IX Rulings and Cases ⋆ Epeak . Independent news and blogs

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Recent Content

Should an Incarcerated Patient Get an Advanced Heart Therapy?

Bioethicists Should Speak Up Against Facilitated Communication

Was This Job Market Study Ethical?

National Research Act at 50: An Ethics Landmark in Need of an Update

Clinical Ethics and a President’s Capacity: Balancing Privacy and Public Interest

Access to Pediatric Assistive Technology: A Moral Test

Griefbots Are Here, Raising Questions of Privacy and Well-being

Finding the Signal in the Noise on Pediatric Gender-Affirming Care

Should he have a vasectomy.

Caring for Patients in Armed Conflict: Narratives from the Front Lines

The Mind is Easy to Penetrate. The Brain, Not So Much

The Overlooked Father of Modern Research Protections

The opinions expressed here are those of the authors, not The Hastings Center.

- What Is Bioethics?

- For the Media

- Hastings Center News

- Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion

- Hastings Center Report

- Focus Areas

- Ethics & Human Research

- Bioethics Careers & Education

- Hastings Bioethics Forum

- FAQs on Human Genomics

- Bioethics Briefings

- Books by Hastings Scholars

- Special Reports

- Ways To Give

- Why We Give

- Gift Planning

Upcoming Events

Previous events, receive our newsletter.

- Terms of Use

Neil Gorsuch

For supreme court justices, faith in law.

Alumni Focus

Judicial Temperament

Neil m. gorsuch ’91 sworn in as u.s. supreme court justice.

April 10, 2017

Neil M. Gorsuch, a 1991 graduate of Harvard Law School, was sworn in today as the 113th justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

- Supreme Court

Neil Gorsuch’s Dissertation Opposes Same-Sex Marriage

Brettschneider is a professor of political science at Brown University

I f Judge Neil Gorsuch is confirmed as the next Supreme Court justice, he would play a decisive role in the future of same-sex marriage in the United States. The Court held in its 2015 Obergefell decision that there is a nationwide right of same-sex couples to marry. But no Supreme Court decision is written in stone. Gorsuch’s statements on the issue in his 2004 Oxford University dissertation for his Doctorate in Philosophy reveal that he thought it obvious that the United States Constitution did not protect a right to same-sex marriage. If he still holds this view, he could join forces with other justices to reverse the Court’s protection of this right.