- Privacy Policy

Home » Primary Data – Types, Methods and Examples

Primary Data – Types, Methods and Examples

Table of Contents

Primary Data

Definition:

Primary Data refers to data that is collected firsthand by a researcher or a team of researchers for a specific research project or purpose. It is original information that has not been previously published or analyzed, and it is gathered directly from the source or through the use of data collection methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, and experiments.

Types of Primary Data

Types of Primary Data are as follows:

Surveys are one of the most common types of primary data collection methods. They involve asking a set of standardized questions to a sample of individuals or organizations, usually through a questionnaire or an online form.

Interviews involve asking open-ended or structured questions to a sample of individuals or groups in person, over the phone, or through video conferencing. They can be conducted in a one-on-one setting or in a focus group.

Observations

Observations involve systematically recording the behavior or activities of individuals or groups in a natural or controlled setting. This type of data collection is often used in fields such as anthropology, sociology, and psychology.

Experiments

Experiments involve manipulating one or more variables and observing the effects on an outcome of interest. They are commonly used in scientific research to establish cause-and-effect relationships.

Case studies

Case studies involve in-depth analysis of a particular individual, group, or organization. They typically involve collecting a variety of data, including interviews, observations, and documents.

Action research

Action research involves collecting data to improve a specific practice or process within an organization or community. It often involves collaboration between researchers and practitioners.

Formats of Primary Data

Some common formats for primary data collection include:

- Textual data : This includes written responses to surveys or interviews, as well as written notes from observations.

- Numeric data: Numeric data includes data collected through structured surveys or experiments, such as ratings, rankings, or test scores.

- Audio data : Audio data includes recordings of interviews, focus groups, or other discussions.

- Visual data: Visual data includes photographs or videos of events, behaviors, or phenomena being studied.

- Sensor data: Sensor data includes data collected through electronic sensors, such as temperature readings, GPS data, or motion data.

- Biological data : Biological data includes data collected through biological samples, such as blood, urine, or tissue samples.

Primary Data Analysis Methods

There are several methods that can be used to analyze primary data collected from research, including:

- Descriptive statistics: Descriptive statistics involve summarizing and describing the characteristics of the data collected, such as mean, median, mode, and standard deviation.

- Inferential statistics: Inferential statistics involve making inferences about a population based on a sample of data. This can include techniques such as hypothesis testing and confidence intervals.

- Qualitative analysis: Qualitative analysis involves analyzing non-numerical data, such as textual data from interviews or observations, to identify themes, patterns, or trends.

- Content analysis: Content analysis involves analyzing textual data to identify and categorize specific words or phrases, allowing researchers to identify themes or patterns in the data.

- Coding : Coding involves categorizing data into specific categories or themes, allowing researchers to identify patterns and relationships in the data.

- Data visualization : Data visualization involves creating graphs, charts, and other visual representations of data to help researchers identify patterns and relationships in the data.

Primary Data Gathering Guide

Here are some general steps to guide you in gathering primary data:

- Define your research question or problem: Clearly define the purpose of your research and the specific questions you want to answer.

- Determine the data collection method : Decide which primary data collection method(s) will be most appropriate to answer your research question or problem.

- Develop a data collection instrument : If you are using surveys or interviews, create a structured questionnaire or interview guide to ensure that you ask the same questions of all participants.

- Identify your target population : Identify the group of individuals or organizations that will provide the data you need to answer your research question or problem.

- Recruit participants: Use various methods to recruit participants, such as email, social media, or advertising.

- Collect the data : Conduct your survey, interview, observation, or experiment, ensuring that you follow your data collection instrument.

- Verify the data : Check the data for completeness, accuracy, and consistency. Resolve any missing data or errors.

- Analyze the data: Use appropriate statistical or qualitative analysis techniques to interpret the data.

- Draw conclusions: Use the results of your analysis to answer your research question or problem.

- Communicate your findings : Share your results through a written report, presentation, or publication.

Examples of Primary Data

Some real-time examples of primary data are:

- Customer surveys: When a company collects data through surveys or questionnaires, they are gathering primary data. For example, a restaurant might ask customers to rate their dining experience.

- Market research : Companies may conduct primary research to understand consumer trends or market demand. For instance, a company might conduct interviews or focus groups to gather information about consumer preferences.

- Scientific experiments: Scientists may gather primary data through experiments, such as observing the behavior of animals or testing new drugs on human subjects.

- Traffic counts: Traffic engineers might collect primary data by monitoring the flow of cars on a particular road to determine how to improve traffic flow.

- Consumer behavior : Companies may use primary data to track consumer behavior, such as how customers use a product or interact with a website.

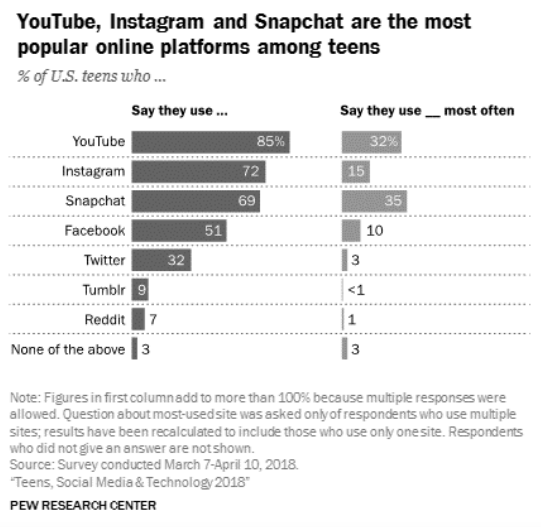

- Social media analytics : Companies can collect primary data by analyzing social media metrics such as likes, comments, and shares to understand how their customers are engaging with their brand.

Applications of Primary Data

Primary data is useful in a wide range of applications, including research, business, and government. Here are some specific applications of primary data:

- Research : Primary data is essential for conducting scientific research, such as in fields like psychology, sociology, and biology. Researchers collect primary data through experiments, surveys, and observations.

- Marketing : Companies use primary data to understand customer needs and preferences, track consumer behavior, and develop marketing strategies. This data is typically collected through surveys, focus groups, and other market research methods.

- Business planning : Primary data can inform business decisions such as product development, pricing strategies, and expansion plans. For example, a company may gather primary data on the buying habits of its customers to decide what products to offer and how to price them.

- Public policy: Primary data is used by government agencies to develop and evaluate public policies. For example, a city government might use primary data on traffic patterns to decide where to build new roads or improve public transportation.

- Education : Primary data is used in education to evaluate student performance, identify areas of need, and develop curriculum. Teachers may gather primary data through assessments, observations, and surveys to improve their teaching methods and help students succeed.

- Healthcare : Primary data is used by healthcare professionals to diagnose and treat illnesses, track patient outcomes, and develop new treatments. Doctors and researchers collect primary data through medical tests, clinical trials, and patient surveys.

- Environmental management: Primary data is used to monitor and manage natural resources and the environment. For example, scientists and environmental managers collect primary data on water quality, air quality, and biodiversity to develop policies and programs aimed at protecting the environment.

- Product testing: Companies use primary data to test new products before they are released to the market. This data is collected through surveys, focus groups, and product testing sessions to evaluate the effectiveness and appeal of the product.

- Crime prevention : Primary data is used by law enforcement agencies to identify crime hotspots, track criminal activity, and develop crime prevention strategies. Police departments may collect primary data through crime reports, surveys, and community meetings to better understand the needs and concerns of the community.

- Disaster response: Primary data is used by emergency responders and disaster management agencies to assess the impact of disasters and develop response plans. This data is collected through surveys, interviews, and observations to identify the needs of affected populations and allocate resources accordingly.

Purpose of Primary Data

The purpose of primary data is to gather information directly from the source, without relying on secondary sources or pre-existing data. This data is collected through research methods such as surveys, interviews, experiments, and observations. Primary data is valuable because it is tailored to the specific research question or problem at hand and is collected with a specific purpose in mind. Some of the main purposes of primary data include:

- To answer research questions: Researchers use primary data to answer specific research questions, such as understanding consumer preferences, evaluating the effectiveness of a program, or testing a hypothesis.

- To gather original information : Primary data provides new and original information that is not available from other sources. This data can be used to make informed decisions, develop new products, or design new programs.

- To tailor research methods: Primary data collection methods can be customized to fit the research question or problem. This allows researchers to gather the most relevant and accurate information possible.

- To control the quality of data: Researchers have greater control over the quality of primary data, as they can design and implement the data collection methods themselves. This reduces the risk of errors or biases that may be present in secondary data sources.

- To address specific populations : Primary data can be collected from specific populations, such as customers, patients, or students. This allows researchers to gather data that is directly relevant to their research question or problem.

When to use Primary Data

Primary data should be used when the specific information required for a research question or problem cannot be obtained from existing data sources. Here are some situations where primary data would be appropriate to use:

- When no secondary data is available: Primary data should be collected when there is no existing data available that addresses the research question or problem.

- When the available secondary data is not relevant: Existing secondary data may not be specific or relevant enough to address the research question or problem at hand.

- When the research requires specific information : Primary data collection allows researchers to gather information that is tailored to their specific research question or problem.

- When the research requires a specific population: Primary data can be collected from specific populations, such as customers, patients, or employees, to provide more targeted and relevant information.

- When the research requires control over the data collection process: Primary data allows researchers to have greater control over the data collection process, which can ensure the data is of high quality and relevant to the research question or problem.

- When the research requires current or up-to-date information: Primary data collection can provide more current and up-to-date information than existing secondary data sources.

Characteristics of Primary Data

Primary data has several characteristics that make it unique and valuable for research purposes. These characteristics include:

- Originality : Primary data is collected for a specific research question or problem and is not previously published or available in any other source.

- Relevance : Primary data is collected to directly address the research question or problem at hand and is therefore highly relevant to the research.

- Accuracy : Primary data collection methods can be designed to ensure the data is accurate and reliable, reducing the risk of errors or biases.

- Timeliness: Primary data is collected in real-time or near real-time, providing current and up-to-date information for the research.

- Specificity : Primary data can be collected from specific populations, such as customers, patients, or employees, providing targeted and relevant information.

- Control : Researchers have greater control over the data collection process, allowing them to ensure the data is collected in a way that is most relevant to the research question or problem.

- Cost : Primary data collection can be more expensive than using existing secondary data sources, as it requires resources such as personnel, equipment, and materials.

Advantages of Primary Data

There are several advantages of using primary data in research. These include:

- Specificity : Primary data collection can be tailored to the specific research question or problem, allowing researchers to gather the most relevant and targeted information possible.

- Control : Researchers have greater control over the data collection process, which can ensure the data is of high quality and relevant to the research question or problem.

- Timeliness : Primary data is collected in real-time or near real-time, providing current and up-to-date information for the research.

- Flexibility : Primary data collection methods can be adjusted or modified during the research process to ensure the most relevant and useful data is collected.

- Greater depth : Primary data collection methods, such as interviews or focus groups, can provide more in-depth and detailed information than existing secondary data sources.

- Potential for new insights : Primary data collection can provide new and unexpected insights into a research question or problem, which may not have been possible using existing secondary data sources.

Limitations of Primary Data

While primary data has several advantages, it also has some limitations that researchers need to be aware of. These limitations include:

- Time-consuming: Primary data collection can be time-consuming, especially if the research requires collecting data from a large sample or a specific population.

- Limited generalizability: Primary data is collected from a specific population, and therefore its generalizability to other populations may be limited.

- Potential bias: Primary data collection methods can be subject to biases, such as social desirability bias or interviewer bias, which can affect the accuracy and reliability of the data.

- Potential for errors: Primary data collection methods can be prone to errors, such as data entry errors or measurement errors, which can affect the accuracy and reliability of the data.

- Ethical concerns: Primary data collection methods, such as interviews or surveys, may raise ethical concerns related to confidentiality, privacy, and informed consent.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Information in Research – Types and Examples

Quantitative Data – Types, Methods and Examples

Research Data – Types Methods and Examples

Qualitative Data – Types, Methods and Examples

Secondary Data – Types, Methods and Examples

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

What is Primary Research and How do I get Started?

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

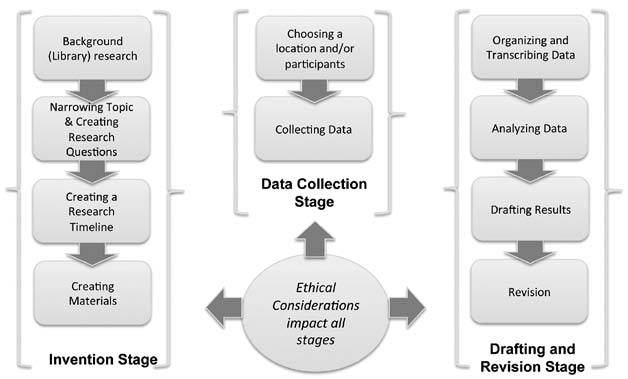

Primary research is any type of research that you collect yourself. Examples include surveys, interviews, observations, and ethnographic research. A good researcher knows how to use both primary and secondary sources in their writing and to integrate them in a cohesive fashion.

Conducting primary research is a useful skill to acquire as it can greatly supplement your research in secondary sources, such as journals, magazines, or books. You can also use it as the focus of your writing project. Primary research is an excellent skill to learn as it can be useful in a variety of settings including business, personal, and academic.

But I’m not an expert!

With some careful planning, primary research can be done by anyone, even students new to writing at the university level. The information provided on this page will help you get started.

What types of projects or activities benefit from primary research?

When you are working on a local problem that may not have been addressed before and little research is there to back it up.

When you are working on writing about a specific group of people or a specific person.

When you are working on a topic that is relatively new or original and few publications exist on the subject.

You can also use primary research to confirm or dispute national results with local trends.

What types of primary research can be done?

Many types of primary research exist. This guide is designed to provide you with an overview of primary research that is often done in writing classes.

Interviews: Interviews are one-on-one or small group question and answer sessions. Interviews will provide a lot of information from a small number of people and are useful when you want to get an expert or knowledgeable opinion on a subject.

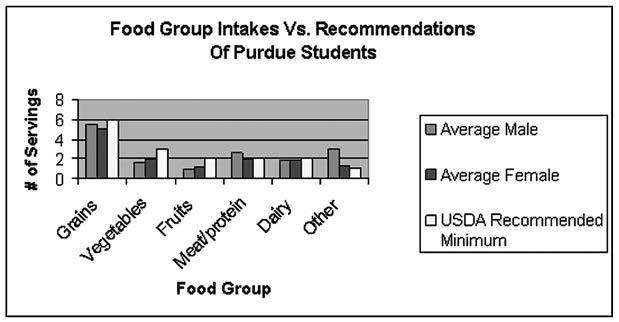

Surveys: Surveys are a form of questioning that is more rigid than interviews and that involve larger groups of people. Surveys will provide a limited amount of information from a large group of people and are useful when you want to learn what a larger population thinks.

Observations: Observations involve taking organized notes about occurrences in the world. Observations provide you insight about specific people, events, or locales and are useful when you want to learn more about an event without the biased viewpoint of an interview.

Analysis: Analysis involves collecting data and organizing it in some fashion based on criteria you develop. They are useful when you want to find some trend or pattern. A type of analysis would be to record commercials on three major television networks and analyze gender roles.

Where do I start?

Consider the following questions when beginning to think about conducting primary research:

- What do I want to discover?

- How do I plan on discovering it? (This is called your research methods or methodology)

- Who am I going to talk to/observe/survey? (These people are called your subjects or participants)

- How am I going to be able to gain access to these groups or individuals?

- What are my biases about this topic?

- How can I make sure my biases are not reflected in my research methods?

- What do I expect to discover?

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Afr J Emerg Med

- v.10(Suppl 2); 2020

Acquiring data in medical research: A research primer for low- and middle-income countries

Vicken totten.

a Kaweah Delta Health Care District (KDHCD), KDHCD Department of Emergency Medicine, Visalia, CA, USA

Erin L. Simon

b Cleveland Clinic Akron General, Department of Emergency Medicine, Akron, OH, USA

Mohammad Jalili

c Department of Emergency Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Hendry R. Sawe

d Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Without data, there is no new knowledge generated. There may be interesting speculation, new paradigms or theories, but without data gathered from the universe, as representative of the truth in the universe as possible, there will be no new knowledge. Therefore, it is important to become excellent at collecting, collating and correctly interpreting data. Pre-existing and new data sources are discussed; variables are discussed, and sampling methods are covered. The importance of a detailed protocol and research manual are emphasized. Data collectors and data collection forms, both electronic and paper-based are discussed. Ensuring subject privacy while also ensuring appropriate data retention must be balanced.

African relevance

- • To get good quality information you first need good quality data

- • Data collection systematically and reproducibly gathers and measures variables to answer research questions.

- • Good data is a result of a well thought out study protocol

The International Federation for Emergency Medicine global health research primer

This paper forms part 9 of a series of ‘how to’ papers, commissioned by the International Federation for Emergency Medicine. It describes data sources, variables, sampling methods, data collection and the value of a clear data protocol. We have also included additional tips and pitfalls that are relevant to emergency medicine researchers.

Data collection is the process of systematically and reproducibly gathering and measuring variables in order to answer research questions, test hypotheses, or evaluate outcomes.

Data is not information. To get good quality information you first need good quality data, then you must curate, analyse and interpret it. Data is comprised of variables. Data collection begins with determining which variables are required, followed by the selection of a sample from a certain population. After that, a data collection tool is used to collect the variables from the selected sample, which is then converted into a data spreadsheet or database. The analysis is done on the database.

Sometimes you gather data yourself. Sometimes you analyse data others collected for different purposes. Ideally, you collect a universal sample, that is, 100%. In real life, you get a limited sample. Preferably, it will be a truly random sample with enough power to answer your question. Unfortunately, you may have to settle for consecutive or convenience sampling. Ideally, your data collectors would be blinded to the outcome of interest, to prevent bias. However, real life is full of biases. Imperfect data may be better than no data; you can often get useful information from imperfect data. Remember the enemy of good is perfect.

Why is good data important?

Acquiring data is the most important step in a research study. The best design with bad data is useless. Bad design produces bad data. The most sophisticated analysis cannot be performed without data; analysing bad data produces erroneous results. Analysis can never be better than the quality of the data on which it was run. Good data has integrity. Data integrity is paramount to learning “Truth in the Universe”. Good data is as complete and as clean, as you can reasonably make it. Clean data ‘has integrity’ when the variables access as much relevant information as possible, and in the same way for each subject.

Some information is very hard to get. You may have to use proxy variables for what you really want to know. A proxy variable is a variable that is not in itself directly relevant, but that serves in place of an unobservable or immeasurable variable. In order for a variable to be a good proxy, it must have a close correlation, not necessarily linear, with the variable of interest. One example for the variable of a specific illness might be a medication list.

Consequences of bad data include an inability to answer the research question; inability to replicate or validate the study; distorted findings and wasted resources; compromised knowledge and even harm to subjects.

Ensure data quality

Good data is a result of a well-thought-out study protocol, which is the written plan for the study. Good planning is the most cost-effective way to ensure data integrity. Good planning is documented by a thorough and detailed protocol, with a comprehensive procedures manual. Poorly written manuals risk incomplete or inconsistent collection of data, in other words, ‘bad data’. The manual should include rigorous, step-by-step instructions on how to administer tests or collect the data. It should cover the ‘who’ (the subject and the researcher); the ‘when’ (the timing), the ‘how’ (methods), and the ‘what’ (a complete listing of variables to be collected). There should also be an identified mechanism to document any changes in procedures that may evolve over the course of the investigation. The study design should be reproducible: so that the protocol can be followed by any other researcher. All data needs to be gathered in the same way. Test (trial-run) your manual before you start your study. If data is collected by several people, make sure there is a sufficient degree of inter-rater reliability.

To get good data, your sample needs to be representative of the population. For others to apply your results, you need to characterize your population, so others can decide if your conclusions are relevant to their population (see Sampling section, below).

Data integrity demands you supervise your study, making sure it is complete and accurate. You may wish to do interim analyses. Keep copies! Keep both the raw data and the data sheets, for the length of time required by law or by Good Research Practice in your country. This will protect you from accusations of falsification of data.

In real life, you may have to deal with any number of sampling and data collection biases. Some of these biases can be measured statistically. Regardless, all the limitations you can think of should be written in your limitations section. The best design you can practically use gives you the best data you can reasonably get. Remember, “you cannot fix with statistics what you fouled up by design.”

Before you acquire your first datum, consider: Do you have a developed protocol and a research manual? Have you sought Ethics Board approval? Do you have an informed consent? Do you have a plan to protect the subject's confidentiality? Do you have a plan for data analysis? Where will you safely store and protect the data? If you have collaborators, have you established, in writing, who owns the data, and who has the right to analyse and publish it?

Types of data: qualitative vs. quantitative data

Numerical data is generally called quantitative; if in words or sentences, it is qualitative. Medical research historically has focused on quantitative methods. Generally, quantitative research is cheaper, easier to gather and easier to analyse. For purposes of this chapter, we will focus on quantitative research.

Qualitative research is about words, sentences, sounds, feeling, emotions, colours and other elements that are non-quantifiable. It requires human intellect to extract themes from the sentences, evaluate the fit of the data to the themes, and to draw the implications of the themes. Primary sources for qualitative data include open ended surveys, interviews, and public meetings. Qualitative research is more common in politics and the social sciences, and will not be further discussed here, except to refer you to other sources.

Quantitative research can include questionnaires with closed-ended questions (open ended questions belong in qualitative research). The data is transformed into numbers and will be analysed with parametric and non-parametric statistical tests. In general, you will derive a mean, mode and median; you will calculate probabilities, make correlation and regressions in order to draw conclusions.

Sources of data: primary vs secondary data

To answer a research question, there are many potential sources of data. Two main categories are primary data and secondary data. Primary data is newly collected data; it can be gathered directly from people's responses (surveys), or from their biometrics (blood pressure, weight, blood tests, etc.). It is still considered primary data if you gather data that was collected for other (medical) purposes by extracting the data from medical records. Medical records can be a rich source of data, but data extraction by hand takes a lot of time.

Secondary data already exists; it has already been published or complied. There are extant local, regional, national and international databases such as Trauma Registries, Disease-specific Registries, Public Health Data, government statistics, and World Health Organization data. Locally, your hospital or clinic may already keep statistics on any number of topics. Combining information from disparate databases may sometimes yield interesting results. For example, in the US, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention keeps databases of reportable diseases, accidents, causes of death and much more. The US Geographic Survey reports the average elevation of American cities. Combining the two databases revealed that, even when gun ownership, drug and alcohol use were statistically controlled for, there was a linear correlation between altitude and suicide rates [ 2 ]. Reno et al., reviewed the existing medical literature (also secondary data), and confirmed the correlation and concluded that the mechanisms have yet to be elucidated [ 3 ].

Collecting good data is often the hardest part of research. Ideally, you would want to collect 100% of the data (universal sampling to reflect target population). One example would be ‘all elderly persons with gout’. In real life, you have access to only a subset of the target population (the accessible population). Further, in your study you will be limited to a subset of the accessible population (the study population). Again, in the ideal world, that limited sample would be truly random, and have enough power to answer your question. You can find free random number generators online. In real life, you may have to settle for consecutive or convenience sampling. Of the two, consecutive sampling has less bias. Sometimes it is important to balance your groups. You may have 2 or 3 treatments (or interventions) and want to have an equal number of each kind. So, you create blocks — of a few times the number of treatments. You randomized within the block. Each time a block is filled, you are assured that you have the right balance of subjects. Blocks are often in groups of six, eight or 12. This is called balanced allocation .

If you must get only a convenience sample – for example because you only have a single data gatherer and can get data only when that person is available – you should, at a minimum, try to get some simple demographics from times when the data gatherer is not available, to see if subjects at that other time are systematically different. For example, if you are looking at injuries, people who are injured when drinking on a Friday night might be systematically different from people who are injured on their way to work on a Monday morning. If you can only collect injury data in the morning, your results will be biased.

Variables are the bits of data you collect. They change from subject to subject and describe the subject numerically. Age (or year of birth); gender; ethnic group or tribe; and geographic location are commonly called simple demographic variables and should be collected and reported for most populations.

Continuous variables are quantified on a continuous scale, such as body weight. Discrete variables use a scale whose units are limited to integers (such as the number of cigarettes smoked per day). Discrete variables have a number of possible values and can resemble continuous variables in statistical analysis and be equivalent for the purpose of designing measurements. A good general rule is to prefer continuous variables because the information they contain provides additional information and improves statistical efficiency (more study power and smaller sample size).

Categorical variables are those not suitable for quantification. They are often measured by classifying them into categories. If there are two possible values (dead or alive), they are dichotomous. If there are more than two categories, they can be classified according to the type of information they provide (polytomous).

Research variables are either predictor (independent) or outcome (dependent) variables. The predictor variables might include such things as “Diabetes, Yes/No”, “Age over 65 — Yes/No”, and “diagnosis of hypertension” (again, Yes/No). The respective outcome might be “lower limb amputation” or “death within 10 years”. Your question might have been, “How much additional risk of amputation does a diagnosis of hypertension add in a person with diabetes?”

Before analysis, variables are coded into numbers and entered into a database. Your Research Manual should describe how to code all the data. When the variables are binary, (male/female; alive/dead) coding them into “0” and “1” makes analysing the data much easier (“1” versus “2” makes it harder). The easiest variables for computers to analyse are binary. In other words, “0” or “1”. Such variables are Yes/No; True/False; Male/Female; 65 or over / under 65, etc. The next easiest are ordinal integers: 1, 2, 3, etc. You might create ordinal numbers from categories (0–9; 10–19; 20–29 years of age, etc.), but in order to be ordinal, they require an obvious sequence. Categorical variables do not have an intrinsic order. “Green” “Brown” and “Orange” are non-ordinal, categorical variables. It is possible to transform categorical variables into binary variables, by making columns where only one of the answers is marked with a “1” (if that variable is present) and all the others are marked “0”. The form of the variables and their distribution will determine the type of statistical analysis possible. Data which must be transformed or cleaned is more prone to error in the cleaning or transformation process.

There are alternative ways to get similar information. For example, if you wanted to know the HIV status of each of your subjects, you could either test each one, or you could ask them. The tests cost more, however; they are less likely to give biased results. How you gather each variable will depend on your resources and will inform the limitations of your study.

Precision of a variable is the degree to which it is reproducible with nearly the same value each time it is measured. Precision has a very important influence on the power of a study. The more precise a measurement, the greater the statistical power of a given sample size to estimate mean values and test your hypotheses. In order to minimize random error in your data, and increase the precision of measurements, you should standardize your measurement methods; train your observers; refine any instruments you may use (such as calibrating instruments); automate instruments when possible (automated blood pressure cuff instead of manual); and repeat your measurements.

Accuracy of the variable is the degree to which it actually represents what it is intended to (Truth in the Universe). This influences the validity of the study. Accuracy is impacted by systemic error (bias). The greater the error, the less accurate the variable. Three common biases are: observer bias (how the measurement is reported); instrument bias (faulty function of an instrument); and subject bias (bad reporting or recall of the measurement by the study subject).

Validity is the degree to which a measurement represents the phenomenon of interest. When validating an abstract concept, search the literature or consult with experts so you can find an already validated data collection instrument (such as a questionnaire). This allows your results to be comparable to prior studies in the same area and strengthens your study methods.

Research manual

Simple research with limited resources does not need a research manual, just a protocol. Nor is there much need if the primary investigator is the only data gatherer and analyser. However, if several persons gather data, it is important that the data be gathered the same way each time.

Prevention is the most cost-effective activity that will ensure the integrity of data collection. A detailed and comprehensive research manual will standardize data collection. Poorly written manuals are vague and ambiguous.

The research manual is based off your protocol. The manual should spell out every step of the data collection process. It should include the name of each variable and specific details about how each variable should be collected. Contingents should be written. For example: “If the patient does not have a left arm, the blood pressure may be taken on the right arm. If the patient has no arms, leg blood pressures may be recorded, but put an ‘*’ beside the reading.” The manual should also include every step of the coding process. The coding manual should describe the name of each variable, and how it should be coded. Both the coder and the statistician will want to refer to that section. The coding section should describe how each variable will be entered into the database. Test the manual to make sure everyone understands it the same way.

Think about various ways a plan can go wrong. Write them down, with preferred solutions. There will always be unexpected changes. They should be added into the manual on a continuing basis. An on-going section where questions, problems and their solutions are all recorded will increase the integrity of your research.

Data collection methods

Before you start data collection, you need to ask yourself what data you are going to collect and how you are going to collect them. Which data, and the amount of data to be collected needs to be defined clearly. Different people (including several data collectors) should have a similar understanding of each variable and how it is measured. Otherwise, the data cannot be relied on. Furthermore, the decision to collect a piece of data needs to be justified. The amount of data collected for the study should be sufficient. A common mistake is to collect too much data without actually knowing what will be done with it. Researchers should identify essential data elements and eliminate those that may seem interesting but are not central to the study hypothesis. Collection of the latter type of data places an unnecessary burden on both the study participants and data collectors.

Different data collection approaches which are commonly used in the conduct of clinical research include questionnaire surveys, patient self-reported data, proxy/informant information, hospital and ambulatory medical records, as well as the collection and analysis of biologic samples. Each of these methods has its own advantages and disadvantages.

Surveys are conducted through administration of standardized or home-grown questionnaires, where participants are asked to respond to a set of questions as yes/no, or perhaps on a Likert type scale. Sometimes open-ended responses are elicited.

Medical records can be important sources of high-quality data and may be used either as the only source of data, or as a complement to information collected through other instruments. Unfortunately, due to the non-standardized nature of data collection, information contained in the medical records may be conflicting or of questionable accuracy. Moreover, the extent of documentation by different providers can vary significantly. These issues can make the construction or use of key study variables very difficult.

Collection of biological materials, as well as various imaging modalities, from the study participants are increasingly being used in clinical research. They need to be performed under standardized conditions, and ethical implications should be considered.

Data collection tool

You may need to collect information on paper. If you do, it is useful to have the actual code which should be entered into the computerized database written on the forms themselves (as well as in the manual). If you have access to an electronic database such as REDcap [a web-based application developed by Vanderbilt University to capture data for clinical research and create databases and projects [ 4 ], you can enter the data directly as you get them ( male ; female ) and the database will automatically convert the data into code. This reduces transcribing errors. Another common electronic database is Excel, which can also be used to manipulate the data. In spite of the advantages of recording data electronically, such as directly into REDcap or Excel, there are advantages to collecting and keeping the original data on paper. Paper data collection forms can be saved for audit or quality control. Furthermore, paper records cannot be remotely hacked. Moreover, if the anonymous electronic database is compromised or corrupted, you can re-create your database.

Data collectors

Good data collectors are worth gold. If they are thorough and ethical, you will get great data. If not, your data may be unusable. Make sure they understand research ethics, the need for protection of human subjects, and the privacy of data. Ideally, your data collectors would be blinded to the outcome of interest, to prevent bias. It is ok to blind data collectors to the research question, but they need to understand that collecting every variable the same way for each subject is essential to data integrity.

Data gatherers should be trained in advance of collecting any data. They need to understand informed consent and have the time to explain a study to the satisfaction of the subjects. The importance of conducting a dry run in an attempt to anticipate and address issues that can arise during data collection cannot be over-stated. It would even be worthwhile to pilot the research manual, to learn if everyone understands it the same way.

Data storage

Data collection, done right, protects the confidentiality of the subject as well as the data. Data must also be properly stored safely and securely. It is reasonable to back up your data in a different, secure, location. You do not want to go to all the trouble of creating a protocol, collecting your data, only to lose it, or have no way to analyse it!

There are many reasons to keep your data safe and secure. Obviously, you do not want to lose your data. You may wish to use the data again. For example, you may wish to combine it with other data for a different study. An additional reason is that you do not want your subjects to risk a ‘loss of privacy’. Still another reason is that institutions and governments may require you to store data for a specified number of years. Know how long you must keep your data. Keep it in a locked cabinet in a secure room, or behind an institutional firewall.

Furthermore, if you keep a cipher , that is, a connector between a subject and their study number, keep that cipher separate from the research data. That way, even if someone learns that subject 302 has an embarrassing condition, they will not know who subject 302 really is.

These days, almost everyone has access to computers and programs, locally or ‘in the cloud’. For statistical analysis, you will need to have your data in electronic form. If you started with paper, consider double entry (two data extractors for each record, then compare the two) for greater accuracy.

Tips on this topic and pitfalls to avoid

Hazard: no research manual.

- • No identified mechanism to document changes in procedures that may evolve over the course of the investigation.

- • Vague description of data collection instruments to be used in lieu of rigorous step-by-step instructions on administering tests

- • Only a partial listing of variables to be collected

- • Forgetting to put instructions on the data collection sheet about how to code the data when transferring to an electronic medium.

Hazard: no assistant training

- • Failure to adequately train data collectors

- • Failure to do a Dry Run/Failure to try enrolling a mock subject

- • Uncertainty about when, how and who should review gathered data.

Hazard: failure to understand data management

- • Data should be easy to understand, and the protocol good enough that another researcher can repeat the study.

- • Data audit: keep raw data and collected data

- • Failure to keep backups

Annotated bibliography

- 1. RCR Data Acquisition and Management. This online book is pretty comprehensive. http://ccnmtl.columbia.edu/projects/rcr/rcr_data/foundation/ (Accessed 2019 June 23)

- 2. Qualitative research – Wikipedia: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qualitative_research (Accessed 2019 June 23) – this is a good overview with references so you can delve deeper if you wish.

- 3. Qualitative Research: Definition, Types, Methods and Examples: https://www.questionpro.com/blog/qualitative-research-methods/ (Accessed 2019 June 23) – this is a good overview with references so you can delve deeper if you wish.

- 4. Qualitative Research Methods: A Data Collector's Field Guide: https://course.ccs.neu.edu/is4800sp12/resources/qualmethods.pdf (Accessed 2019 June 23) – another on-line resource about data collection.

Additional reading about statistical variables

- 1. Types of Variables in Statistics and Research: A List of Common and Uncommon Types of Variables. https://www.statisticshowto.datasciencecentral.com/probability-and-statistics/types-of-variables/

- 2. Research Variables: Dependent, Independent, Control, Extraneous & Moderator. https://study.com/academy/lesson/research-variables-dependent-independent-control-extraneous-moderator.html

- 3. Knatterud GL. Rockhold FW. George SL. Barton FB. Davis CE. Fairweather WR. Honohan, T. Mowery R. O'Neill R. (1998). Guidelines for quality assurance in multicenter trials: a position paper. Controlled Clinical Trials, 19:477–493.

- 4. Whitney CW. Lind BK. Wahl PW. (1998). Quality assurance and quality control in longitudinal studies. Epidemiologic Reviews, 20 [ 1 ]: 71–80.

Additional relevant information to consider

Consider who owns the data before and after collection (this brings up questions of consent, privacy, sponsorship and data-sharing, most of which are beyond the scope of this paper).

Authors' contribution

Authors contributed as follow to the conception or design of the work; the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work; and drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content: ES contributed 70%; VT, MJ and HS contributed 10% each. All authors approved the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Primary Data: Definition, Examples & Collection Methods

Introduction

What is meant by primary data, what is the difference between primary and secondary data, what are examples of primary data, primary data collection methods, advantages of primary data collection, disadvantages of primary data collection, ethical considerations for primary data.

Understanding the type of data being analyzed is crucial for drawing accurate conclusions in qualitative research. Collecting primary data directly from the source offers unique insights that can benefit researchers in various fields.

This article provides a comprehensive guide on primary data, illustrating its definition, how it stands apart from secondary data , pertinent examples, and the common methods employed in the primary data collection process. Additionally, we will explore the advantages and disadvantages associated with primary data acquisition.

Primary data refers to information that is collected firsthand by the researcher for a specific research purpose. Unlike secondary data, which is already available and has been collected for some other objective, primary data is raw and unprocessed, offering fresh insights directly related to the research question at hand. This type of data is gathered through various methods such as surveys , interviews , experiments, and observations , allowing researchers to obtain tailored and precise information.

The main characteristic of primary data is its relevancy to the specific study. Since it is collected with the research objectives and questions in mind, it directly addresses the issues or hypotheses under investigation. This direct connection enhances the validity and accuracy of the research findings, as the data is not diluted or missing important information relevant to the research question.

Moreover, primary data provides the most current information available, making it especially valuable in fast-changing fields or situations where timely data is crucial. By analyzing primary data, researchers can draw unique conclusions and develop original insights that contribute significantly to their field of study.

Understanding the distinction between primary and secondary data is fundamental in the realm of research, as it influences the research design , methodology , and analysis . Primary data is information collected firsthand for a specific research purpose. It is original and unprocessed, providing new insights directly relevant to the researcher's questions or objectives. Common methods of collecting data from primary sources include observations , surveys , interviews , and experiments, each allowing the researcher to gather specific, targeted information.

Conversely, secondary data refers to information that was collected by someone else for a different purpose and is subsequently used by a researcher for a new study. This data can come from a primary source such as an academic journal, a government report, a set of historical records, or a previous research study. While secondary data is invaluable for providing context, background, and supporting evidence, it may not be as precisely tailored to the specific research questions as primary data.

The key differences between these two types of data also extend to their advantages and disadvantages concerning accessibility, cost, and time. Primary data is typically more time-consuming and expensive to collect but offers specificity and relevance that is unmatched by secondary data. On the other hand, secondary data is usually more accessible and less costly, as it leverages existing information, although it may not align perfectly with the current research needs and might be outdated or less specific.

In terms of accuracy and reliability, primary data allows for greater control over the quality and methodology of the data collected, reflecting the current scenario accurately. However, secondary data's reliability depends on the original data collection's accuracy and the context in which it was gathered, which might not be fully verifiable by the new researcher.

Synthesizing primary and secondary data

While primary and secondary data each have distinct roles in research, synthesizing both types can provide a more comprehensive understanding of the research topic . Integrating primary data with secondary data allows researchers to contextualize their firsthand findings within the broader literature and existing knowledge.

This approach can enhance the depth and relevance of the research, providing a more nuanced analysis that leverages the detailed, current insights of primary data alongside the extensive, contextual background of secondary data.

For example, primary data might offer detailed consumer behavior insights, which researchers can then compare with broader market trends or historical data from secondary sources. This synthesis can reveal patterns, corroborate findings, or identify anomalies, enriching the research's analytical value and implications.

Ultimately, combining primary and secondary data helps build a robust research framework, enabling a more informed and comprehensive exploration of the research question .

Primary data collection is a cornerstone of research in the social sciences, providing firsthand insights that are crucial for understanding complex human behaviors and societal structures. This direct approach to data gathering allows researchers to uncover rich, context-specific information.

The following subsections highlight examples of primary data across various social science disciplines, showcasing the versatility and depth of these research methods.

Economic behaviors in market research

Market research within economics often relies on primary data to understand consumer preferences, spending habits, and decision-making processes. For instance, a study may collect primary data through surveys or interviews to gauge consumer reactions to a new product or service.

This information can reveal economic behaviors, such as price sensitivity and brand loyalty, offering valuable insights for businesses and policymakers.

Voting patterns in political science

In political science, researchers collect primary data to analyze voting patterns and political engagement. Through exit polls and surveys conducted during elections, researchers can obtain firsthand accounts of voter preferences and motivations.

This data is pivotal in understanding the dynamics of electoral politics, voter turnout, and the influence of campaign strategies on public opinion.

Cultural practices in anthropology

Anthropologists gather primary data to explore cultural practices and beliefs, often through ethnographic studies . By immersing themselves in a community, researchers can directly observe rituals, social interactions, and traditions.

For example, a study might focus on marriage ceremonies, food customs, or religious practices within a particular culture, providing in-depth insights into the community's way of life.

Social interactions in sociology

Sociologists utilize primary data to investigate the intricacies of social interactions and societal structures. Observational studies , for instance, can reveal how individuals behave in group settings, how social norms are enforced, and how social hierarchies influence behavior.

By analyzing these interactions within settings like schools, workplaces, or public spaces, sociologists can uncover patterns and dynamics that shape social life.

Quality research starts with powerful analysis tools

Make ATLAS.ti your solution for qualitative data analysis. Download a free trial.

Primary data collection is an integral aspect of research, enabling investigators to gather fresh, relevant data directly related to their study objectives. This direct engagement provides rich, nuanced insights that are critical for in-depth analysis. Selecting the appropriate data collection method is pivotal, as it influences the study's overall design, data quality, and conclusiveness.

Below are some of the different types of primary data utilized across various research disciplines, each offering unique benefits and suited to different research needs.

In-person and online surveys collect data from a large audience efficiently. By utilizing structured questionnaires, researchers can gather data on a wide range of topics, such as attitudes, preferences, behaviors, or factual information.

Surveys can be distributed through various channels, including online platforms, phone, mail, or in-person, allowing for flexibility in reaching diverse populations.

Interviews provide an in-depth look into the respondents' perspectives, experiences, or opinions. They can range from highly structured formats to open-ended, conversational styles, depending on the research goals.

Interviews are particularly valuable for exploring complex issues, understanding personal narratives, and gaining detailed insights that are not easily captured through other methods.

Focus groups

Focus groups involve guided discussions with a small group of participants, allowing researchers to explore collective views, uncover trends in perceptions, and stimulate debate on a specific topic.

This method is particularly useful for generating rich qualitative data, understanding group dynamics, and identifying variations in opinions across different demographic groups.

Observations

Observational research involves systematically watching and recording behaviors and interactions in their natural context. It can be conducted in various settings, such as schools, workplaces, or public areas, providing authentic insights into real-world behaviors.

The observation method can be either participant, where the observer is involved in the activities, or non-participant, where the researcher observes without interaction.

Experiments

Experiments are a fundamental method in scientific research, allowing researchers to control variables and measure effects accurately.

By manipulating certain factors and observing the outcomes, experiments can establish causal relationships, providing a robust basis for testing hypotheses and drawing conclusions.

Case studies

Case studies offer an in-depth examination of a particular instance or phenomenon, often involving a comprehensive analysis of individuals, organizations, events, or other entities.

This method is particularly suited to exploring new or complex issues, providing detailed contextual analysis, and uncovering underlying mechanisms or principles.

Ethnography

As a key method in anthropology, ethnography involves extended observation of a community or culture, often through fieldwork. Researchers immerse themselves in the environment, participating in and observing daily life to gain a deep understanding of social practices, norms, and values.

Ethnography is invaluable for exploring cultural phenomena, understanding community dynamics, and providing nuanced interpretations of social behavior.

Primary data collection is a fundamental aspect of research, offering distinct advantages that enhance the quality and relevance of study findings. By gathering high-quality primary data firsthand, a research project can obtain specific, up-to-date information that directly addresses their research questions or hypotheses. This section explores four key advantages of primary data collection, highlighting how it contributes to robust and insightful research outcomes.

Specificity

One of the most significant advantages of primary data collection is its specificity. Data gathered firsthand is tailored specifically to the research question or hypothesis, ensuring that the information is directly relevant and applicable to the study's objectives. This level of specificity enhances the precision of the research, allowing for a more targeted analysis and reducing the likelihood of extraneous variables influencing the results.

Primary data collection offers the advantage of currency, providing the most recent information available. This is particularly crucial in fields where data rapidly change, such as market trends, technological advancements, or social dynamics. By accessing current data, researchers can draw conclusions that are timely and reflective of the present context, adding significant value and relevance to their findings.

Control over data quality

When collecting primary data, researchers have direct control over the data quality. They can design the data collection process, choose the sample, and implement quality assurance measures to ensure valid and reliable data. This direct involvement allows researchers to address potential biases, minimize errors, and adjust methodologies as needed, ensuring that the data is accurate and representative of the population under study.

Exclusive insights

Gathering primary data provides exclusive insights that might not be available through secondary sources. By collecting unique data sets, researchers can explore uncharted territories, generate new theories, and contribute original findings to their field. This exclusivity not only advances academic knowledge but also offers competitive advantages in applied settings, such as business or policy development, where novel insights can lead to innovative solutions and strategic advancements.

While primary data collection offers numerous benefits, it also comes with distinct disadvantages that researchers must consider. These drawbacks can impact the feasibility, reliability, and overall outcome of a study. Understanding these limitations is crucial for researchers to design effective and comprehensive research methodologies . Below, we explore four significant disadvantages of primary data collection.

Time-consuming process

Primary data collection often requires a significant investment of time. From designing the data collection tools and protocols to actually gathering the data and analyzing results, each step can take a long time to carry out. For instance, conducting in-depth interviews , surveys , or extensive observations demands considerable time for both preparation and execution. This extended timeline can be a significant hurdle, especially in fields where timely data is crucial.

The financial implications of primary data collection can be substantial. Resources are needed for various stages of the process, including material creation, data gathering, personnel, and data analysis . For example, organizing focus groups or conducting large-scale surveys involves logistical expenses, compensation for participants, and possibly travel costs. Such financial requirements can limit the scope of the research or even render it unfeasible for underfunded projects.

Limited scope

Primary data collection is typically focused on a specific research question or context, which may limit the breadth of the data. While this specificity provides detailed insights into the chosen area of study, it may not offer a comprehensive overview of the subject. For example, a case study provides in-depth data about a particular case, but its findings may not be generalizable to other contexts or populations, limiting the scope of the research conclusions.

Potential for data collection bias

The process of collecting primary data is susceptible to various biases , which can compromise the data's accuracy and reliability. Researcher bias, selection bias, or response bias can skew results, leading to misleading conclusions. For instance, the presence of an observer might influence participants' behavior, or poorly designed survey questions might lead to ambiguous or skewed responses. Mitigating these biases requires meticulous planning and execution, but some level of bias is often inevitable.

Ethical considerations are paramount in the realm of primary data collection , ensuring the respect and dignity of participants are maintained while preserving the integrity of the research process. Researchers are obligated to adhere to ethical standards that promote trust, accountability, and scientific excellence. This section delves into key ethical principles that must be considered when collecting primary data.

Informed consent

Informed consent is the cornerstone of ethical research. Participants must be fully informed about the study's purpose, procedures, potential risks, and benefits, as well as their right to withdraw at any time without penalty. This information should be communicated in a clear, understandable manner, ensuring participants can make an informed decision about their involvement. Documented consent, whether written or verbal, is essential to demonstrate that participants have agreed to partake in the study voluntarily, understanding all its aspects.

Confidentiality and privacy

Protecting participants' confidentiality and privacy is crucial to uphold their rights and the data's integrity. Researchers must implement measures to ensure that personal information is securely stored and only accessible to authorized team members. Data should be anonymized or de-identified to prevent the identification of individual participants in reports or publications. Researchers must also be transparent about any data sharing plans and obtain consent for such activities, ensuring participants are aware of who might access their information and for what purposes.

Data integrity and reporting

Maintaining data integrity is fundamental to ethical research practices. Researchers are responsible for collecting, analyzing, and presenting data accurately and transparently, without fabrication, falsification, or inappropriate data manipulation. Reporting should be honest and comprehensive, reflecting all relevant findings, including any that contradict the research hypotheses. Researchers should also disclose any conflicts of interest that might influence the study's outcomes, maintaining transparency throughout the research process.

Minimizing harm

Research should be designed and conducted in a way that minimizes any potential harm to participants. This includes considering physical, psychological, emotional, and social risks. Researchers must take steps to reduce any discomfort or adverse effects, providing support or referrals if participants experience distress. Ethical research also involves selecting appropriate methodologies that align with the study's objectives while safeguarding participants' well-being, ensuring that the research's potential benefits justify any risks involved.

Make the most of your data with ATLAS.ti

Our powerful tools make research easier and faster than ever. Get started with a free trial today.

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Primary Research: What It Is, Purpose & Methods + Examples

As we continue exploring the exciting research world, we’ll come across two primary and secondary data approaches. This article will focus on primary research – what it is, how it’s done, and why it’s essential.

We’ll discuss the methods used to gather first-hand data and examples of how it’s applied in various fields. Get ready to discover how this research can be used to solve research problems , answer questions, and drive innovation.

What is Primary Research: Definition

Primary research is a methodology researchers use to collect data directly rather than depending on data collected from previously done research. Technically, they “own” the data. Primary research is solely carried out to address a certain problem, which requires in-depth analysis .

There are two forms of research:

- Primary Research

- Secondary Research

Businesses or organizations can conduct primary research or employ a third party to conduct research. One major advantage of primary research is this type of research is “pinpointed.” Research only focuses on a specific issue or problem and on obtaining related solutions.

For example, a brand is about to launch a new mobile phone model and wants to research the looks and features they will soon introduce.

Organizations can select a qualified sample of respondents closely resembling the population and conduct primary research with them to know their opinions. Based on this research, the brand can now think of probable solutions to make necessary changes in the looks and features of the mobile phone.

Primary Research Methods with Examples

In this technology-driven world, meaningful data is more valuable than gold. Organizations or businesses need highly validated data to make informed decisions. This is the very reason why many companies are proactive in gathering their own data so that the authenticity of data is maintained and they get first-hand data without any alterations.

Here are some of the primary research methods organizations or businesses use to collect data:

1. Interviews (telephonic or face-to-face)

Conducting interviews is a qualitative research method to collect data and has been a popular method for ages. These interviews can be conducted in person (face-to-face) or over the telephone. Interviews are an open-ended method that involves dialogues or interaction between the interviewer (researcher) and the interviewee (respondent).

Conducting a face-to-face interview method is said to generate a better response from respondents as it is a more personal approach. However, the success of face-to-face interviews depends heavily on the researcher’s ability to ask questions and his/her experience related to conducting such interviews in the past. The types of questions that are used in this type of research are mostly open-ended questions . These questions help to gain in-depth insights into the opinions and perceptions of respondents.

Personal interviews usually last up to 30 minutes or even longer, depending on the subject of research. If a researcher is running short of time conducting telephonic interviews can also be helpful to collect data.

2. Online surveys

Once conducted with pen and paper, surveys have come a long way since then. Today, most researchers use online surveys to send to respondents to gather information from them. Online surveys are convenient and can be sent by email or can be filled out online. These can be accessed on handheld devices like smartphones, tablets, iPads, and similar devices.

Once a survey is deployed, a certain amount of stipulated time is given to respondents to answer survey questions and send them back to the researcher. In order to get maximum information from respondents, surveys should have a good mix of open-ended questions and close-ended questions . The survey should not be lengthy. Respondents lose interest and tend to leave it half-done.

It is a good practice to reward respondents for successfully filling out surveys for their time and efforts and valuable information. Most organizations or businesses usually give away gift cards from reputed brands that respondents can redeem later.

3. Focus groups

This popular research technique is used to collect data from a small group of people, usually restricted to 6-10. Focus group brings together people who are experts in the subject matter for which research is being conducted.

Focus group has a moderator who stimulates discussions among the members to get greater insights. Organizations and businesses can make use of this method, especially to identify niche markets to learn about a specific group of consumers.

4. Observations

In this primary research method, there is no direct interaction between the researcher and the person/consumer being observed. The researcher observes the reactions of a subject and makes notes.

Trained observers or cameras are used to record reactions. Observations are noted in a predetermined situation. For example, a bakery brand wants to know how people react to its new biscuits, observes notes on consumers’ first reactions, and evaluates collective data to draw inferences .

Primary Research vs Secondary Research – The Differences

Primary and secondary research are two distinct approaches to gathering information, each with its own characteristics and advantages.

While primary research involves conducting surveys to gather firsthand data from potential customers, secondary market research is utilized to analyze existing industry reports and competitor data, providing valuable context and benchmarks for the survey findings.

Find out more details about the differences:

1. Definition

- Primary Research: Involves the direct collection of original data specifically for the research project at hand. Examples include surveys, interviews, observations, and experiments.

- Secondary Research: Involves analyzing and interpreting existing data, literature, or information. This can include sources like books, articles, databases, and reports.

2. Data Source

- Primary Research: Data is collected directly from individuals, experiments, or observations.

- Secondary Research: Data is gathered from already existing sources.

3. Time and Cost

- Primary Research: Often time-consuming and can be costly due to the need for designing and implementing research instruments and collecting new data.

- Secondary Research: Generally more time and cost-effective, as it relies on readily available data.

4. Customization

- Primary Research: Provides tailored and specific information, allowing researchers to address unique research questions.

- Secondary Research: Offers information that is pre-existing and may not be as customized to the specific needs of the researcher.

- Primary Research: Researchers have control over the research process, including study design, data collection methods , and participant selection.

- Secondary Research: Limited control, as researchers rely on data collected by others.

6. Originality

- Primary Research: Generates original data that hasn’t been analyzed before.

- Secondary Research: Involves the analysis of data that has been previously collected and analyzed.

7. Relevance and Timeliness

- Primary Research: Often provides more up-to-date and relevant data or information.

- Secondary Research: This may involve data that is outdated, but it can still be valuable for historical context or broad trends.

Advantages of Primary Research

Primary research has several advantages over other research methods, making it an indispensable tool for anyone seeking to understand their target market, improve their products or services, and stay ahead of the competition. So let’s dive in and explore the many benefits of primary research.

- One of the most important advantages is data collected is first-hand and accurate. In other words, there is no dilution of data. Also, this research method can be customized to suit organizations’ or businesses’ personal requirements and needs .

- I t focuses mainly on the problem at hand, which means entire attention is directed to finding probable solutions to a pinpointed subject matter. Primary research allows researchers to go in-depth about a matter and study all foreseeable options.

- Data collected can be controlled. I T gives a means to control how data is collected and used. It’s up to the discretion of businesses or organizations who are collecting data how to best make use of data to get meaningful research insights.

- I t is a time-tested method, therefore, one can rely on the results that are obtained from conducting this type of research.

Disadvantages of Primary Research

While primary research is a powerful tool for gathering unique and firsthand data, it also has its limitations. As we explore the drawbacks, we’ll gain a deeper understanding of when primary research may not be the best option and how to work around its challenges.

- One of the major disadvantages of primary research is it can be quite expensive to conduct. One may be required to spend a huge sum of money depending on the setup or primary research method used. Not all businesses or organizations may be able to spend a considerable amount of money.

- This type of research can be time-consuming. Conducting interviews and sending and receiving online surveys can be quite an exhaustive process and require investing time and patience for the process to work. Moreover, evaluating results and applying the findings to improve a product or service will need additional time.

- Sometimes, just using one primary research method may not be enough. In such cases, the use of more than one method is required, and this might increase both the time required to conduct research and the cost associated with it.

Every research is conducted with a purpose. Primary research is conducted by organizations or businesses to stay informed of the ever-changing market conditions and consumer perception. Excellent customer satisfaction (CSAT) has become a key goal and objective of many organizations.

A customer-centric organization knows the importance of providing exceptional products and services to its customers to increase customer loyalty and decrease customer churn. Organizations collect data and analyze it by conducting primary research to draw highly evaluated results and conclusions. Using this information, organizations are able to make informed decisions based on real data-oriented insights.

QuestionPro is a comprehensive survey platform that can be used to conduct primary research. Users can create custom surveys and distribute them to their target audience , whether it be through email, social media, or a website.