- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Unconscious Bias Training That Works

- Francesca Gino

- Katherine Coffman

To become more diverse, equitable, and inclusive, many companies have turned to unconscious bias (UB) training. By raising awareness of the mental shortcuts that lead to snap judgments—often based on race and gender—about people’s talents or character, it strives to make hiring and promotion fairer and improve interactions with customers and among colleagues. But most UB training is ineffective, research shows. The problem is, increasing awareness is not enough—and can even backfire—because sending the message that bias is involuntary and widespread may make it seem unavoidable.

UB training that gets results, in contrast, teaches attendees to manage their biases, practice new behaviors, and track their progress. It gives them information that contradicts stereotypes and allows them to connect with colleagues whose experiences are different from theirs. And it’s not a onetime session; it entails a longer journey and structural organizational changes.

In this article the authors describe how rigorous UB programs at Microsoft, Starbucks, and other organizations help employees overcome denial and act on their awareness, develop the empathy that combats bias, diversify their networks, and commit to improvement.

Increasing awareness isn’t enough. Teach people to manage their biases, change their behavior, and track their progress.

Idea in Brief

The problem.

Conventional training to combat unconscious bias and make the workplace more diverse, equitable, and inclusive isn’t working.

This training aims to raise employees’ awareness of biases based on race or gender. But by also sending the message that such biases are involuntary and widespread, it can make people feel that they’re unavoidable.

The Solution

Companies must go beyond raising awareness and teach people to manage biases and change behavior. Firms should also collect data on diversity, employees’ perceptions, and training effectiveness; introduce behavioral “nudges”; and rethink policies.

Across the globe, in response to public outcry over racist incidents in the workplace and mounting evidence of the cost of employees’ feeling excluded, leaders are striving to make their companies more diverse, equitable, and inclusive. Unconscious bias training has played a major role in their efforts. UB training seeks to raise awareness of the mental shortcuts that lead to snap judgments—often based on race and gender—about people’s talents or character. Its goal is to reduce bias in attitudes and behaviors at work, from hiring and promotion decisions to interactions with customers and colleagues.

- Francesca Gino is a behavioral scientist and the Tandon Family Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School. She is the author of Rebel Talent and Sidetracked . francescagino

- KC Katherine Coffman is an associate professor of business administration at Harvard Business School. Her research focuses on how stereotypes affect beliefs and behavior.

Partner Center

What Is Unconscious Bias (And How You Can Defeat It)

Research-based strategies for how to identify and defeat unconscious bias..

Posted July 13, 2020 | Reviewed by Lybi Ma

- What Is the Unconscious

- Find a therapist near me

How do you defeat unconscious bias? First, you need to know what it is.

Unconscious bias (also known as implicit bias) refers to unconscious forms of discrimination and stereotyping based on race, gender , sexuality , ethnicity , ability, age, and so on. It differs from cognitive bias, which is a predictable pattern of mental errors that result in us misperceiving reality and, as a result, deviating away from the most likely way of reaching our goals .

In other words, from the perspective of what is best for us as individuals, falling for a cognitive bias always harms us by lowering our probability of getting what we want. Despite cognitive biases sometimes leading to discriminatory thinking and feeling patterns, these are two separate and distinct concepts.

Cognitive biases are common across humankind and relate to the particular wiring of our brains, while unconscious bias relates to perceptions between different groups and are specific for the society in which we live. For example, I bet you don’t care or even think about whether someone is a noble or a commoner, yet that distinction was fundamentally important a few centuries ago across Europe. To take another example – a geographic instead of one across time – most people in the US don’t have strong feelings about Sunni vs. Shiite Muslims, yet this distinction is incredibly meaningful in many parts of the world.

Black Americans suffer from police harassment and violence at a much higher rate than white people, people do try to defend the police by claiming that black people are more violent and likely to break the law than whites. They thus attribute police harassment to the internal characteristics of black people (implying that it is deserved), not to the external context of police behavior.

In reality, research shows that black people are harassed and harmed by police at a much higher rate for the same kind of activity. A white person walking by a cop, for example, is statistically much less likely to be stopped and frisked than a black one. At the other end of things, a white person resisting arrest is much less likely to be violently beaten than a black one. In other words, statistics show that the higher rate of harassment and violence against black Americans by police is due to the prejudice of the police officers, at least to a large extent.

However, this discrimination is not necessarily intentional. Sometimes, it indeed is deliberate, with white police officers consciously believing that black Americans deserve much more scrutiny than whites. At other times, the discriminatory behavior results from unconscious, implicit thought processes that the police officer would not consciously endorse.

Interestingly, research shows that many black police officers have an unconscious prejudice against other black people, perceiving them in a more negative light than white people when evaluating potential suspects. This unconscious bias carried by many, not all, black police officers helps show that such prejudices come – at least to a significant extent – from internal cultures within police departments, rather than pre-existing racist attitudes before someone joins a police department.

Such cultures are perpetuated by internal norms, policies, and training procedures, and any police department wishing to address unconscious bias needs to address internal culture first and foremost, rather than attributing racism to individual officers. In other words, instead of saying it’s a few bad apples in a barrel of overall good ones, the key is recognizing that implicit bias is a systemic issue, and the structure and joints of the barrel need to be fixed.

The crucial thing to highlight is that there is no shame or blame in implicit bias, as it’s not stemming from any fault in the individual. This no-shame approach decreases the fight, freeze, or flight defensive response among reluctant people, helping them hear and accept the issue.

With these additional statistics and discussion of implicit bias, the issue is generally settled. Still, from their subsequent behavior, it’s clear that some people don’t immediately internalize this evidence. It’s much more comforting for them to feel that police officers are right and anyone targeted by police deserves it; in turn, they are highly reluctant to accept the need to focus more efforts and energy on protecting black Americans from police violence, due to the structural challenges facing these groups.

The issue of unconscious bias doesn’t match their intuitions and thus they reject this concept, despite extensive and strong evidence for its pervasive role in policing. It takes a series of subsequent follow-up conversations and interventions to move the needle.

This example of how to fight unconscious bias illustrates broader patterns you need to follow to address such problems to address unconscious bias to make the best people decisions. After all, our gut reactions lead us to make poor judgment choices, when we simply follow our intuitions.

1) Instead, you need to start by learning about the kind of problems that result from unconscious bias yourself, so that you know what you’re trying to address.

2) Then, you need to convey to people who you want to influence, such as your employees or any other group or even yourself, that there should be no shame or guilt in acknowledging our instincts.

3) Next, you need to convey the dangers associated with following their intuitions, to build up an emotional investment into changing behaviors.

4) Then, you need to convey the right mental habits that will help them make the best choices.

It takes a long-term commitment and constant discipline and efforts to overcome unconscious bias.

Originally Published at Disaster Avoidance Experts on June 23, 2020.

Tsipursky, G. (2019). Never Go With Your Gut: How Pioneering Leaders Make the Best Decisions and Avoid Business Disasters. Newburyport, MA: Career Press.

Gleb Tsipursky, Ph.D. , is on the editorial board of the journal Behavior and Social Issues. He is in private practice.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

It’s increasingly common for someone to be diagnosed with a condition such as ADHD or autism as an adult. A diagnosis often brings relief, but it can also come with as many questions as answers.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Research bias

- What Is Unconscious Bias? | Definition & Examples

What Is Unconscious Bias? | Definition & Examples

Published on February 27, 2023 by Kassiani Nikolopoulou and Tegan George. Revised on August 9, 2024.

Unconscious bias refers to the automatic associations and reactions that arise when we encounter a person or group. Instead of maintaining neutrality, we tend to associate positive or negative stereotypes with certain groups and let these biases influence our behavior towards them.

Unconscious bias can lead to discriminatory behavior in healthcare, the workplace, educational settings, and beyond.

Table of contents

What is unconscious bias, what causes unconscious bias, unconscious vs. explicit bias, unconscious bias examples, how to reduce unconscious bias, other types of research bias, frequently asked questions about unconscious bias.

Unconscious bias is an implicit preference for (or aversion towards) a particular person or entity. These feelings can be either positive or negative, but they cause us to act unfairly towards others. This can manifest as affinity bias , or the tendency to favor people who are similar to us, but any identity-based aspect (e.g., age, gender identity, socioeconomic background, etc.) can be the target of unconscious bias.

We are, by definition, unaware of biases that affect our decisions and judgments: this is why they are called unconscious. For example, when most people hear the word “nurse,” they are more likely to picture a female, even if they don’t consciously believe that only women can be nurses. Because unconscious bias operates below our awareness, it can be challenging to acknowledge and manage.

There are several factors at play within our unconscious biases:

- Brain categorization . Humans have a natural tendency to assign everything into a relevant category. This happens unconsciously, but this categorizing also leads us to assign a positive or negative association to each category. Categories allow our brains to know what to do or how to behave, but classifications often cause us to overgeneralize.

- We rely on heuristics. We often rely on “automatic” information processing to go through our day, involving little conscious thought. These mental shortcuts allow us to exert little mental effort in our everyday lives, and make swift judgments when needed.

- Social and cultural dynamics. Our upbringing and social environment, as well as any direct and indirect experiences with members of various social groups, imprint on us. These shape our perceptions, both consciously and subconsciously.

Both unconscious and explicit bias involve judging others based on our assumptions rather than objective facts. However, the two are actually quite different.

- Unconscious bias occurs when we have an inclination for or against a person or group that emerges automatically .

- Explicit bias includes positive or negative attitudes that we are fully aware of and openly express. These attitudes form part of our worldview.

Despite their differences, unconscious bias can be just as problematic as explicit bias. Both can lead to discriminatory behavior.

Unconscious bias can lead to discriminatory behavior when it comes to hiring a diverse workforce.

Both positive and negative unconscious beliefs operate outside our awareness and can lead to structural and systemic inequalities. If we want to reduce it, we must first become conscious of it. The following strategies can help:

- Taking the Harvard Implicit Bias Association Test (IAT) can help you realize that everyone, including you, has implicit or unconscious biases. Recognising them for what they are increases the likelihood that next time you won’t let these hidden biases affect your behaviour.

- Seek out positive intergroup contact. Unconscious bias towards a particular group can be reduced through interaction with members of that group. For example, you can make it a point to engage in activities that include individuals from diverse backgrounds.

- Counter-stereotyping. Exposure to information that defies persistent stereotypes about certain groups, such as images of male nurses, can counter gender-based stereotypes.

- Unconscious bias training. Although raising awareness is important, it’s not sufficient to overcome unconscious biases. The most successful training programs are ones that allow individuals to discover their biases in a non-confrontational manner, helping them seek out the tools to help reduce and manage these biases.

Cognitive bias

- Confirmation bias

- Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- Availability heuristic

- Halo effect

- Framing effect

- Optimism bias

- Negativity bias

- Affect heuristic

- Representativeness heuristic

- Anchoring heuristic

- Primacy bias

Selection bias

- Sampling bias

- Ascertainment bias

- Attrition bias

- Self-selection bias

- Survivorship bias

- Nonresponse bias

- Undercoverage bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Observer bias

- Omitted variable bias

- Publication bias

- Pygmalion effect

- Recall bias

- Social desirability bias

- Placebo effect

- Actor-observer bias

- Ceiling effect

- Ecological fallacy

- Affinity bias

Implicit bias refers to attitudes that affect our understanding, actions, and decisions in an unconscious manner. These attitudes can be either positive or negative. Affinity bias , or the tendency to gravitate towards people who are similar to us, is a type of implicit or unconscious bias.

Similarity bias or affinity bias is a type of unconscious bias. It occurs when we show preference for people who are similar to us (i.e., people with whom we share a common attribute, such as physical appearance, hobbies, or educational background).

The opposite of explicit bias is implicit bias (or unconscious bias). This refers to all the subconscious evaluations we have formed about a certain group. Implicit bias can influence our interactions with members of this group without us realizing.

Demand characteristics are a type of extraneous variable that can affect the outcomes of the study. They can invalidate studies by providing an alternative explanation for the results.

These cues may nudge participants to consciously or unconsciously change their responses, and they pose a threat to both internal and external validity . You can’t be sure that your independent variable manipulation worked, or that your findings can be applied to other people or settings.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Nikolopoulou, K. & George, T. (2024, August 09). What Is Unconscious Bias? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved September 16, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-bias/unconscious-bias/

Is this article helpful?

Kassiani Nikolopoulou

Other students also liked, what is implicit bias | definition & examples, what is explicit bias | definition & examples, what is affinity bias | definition & examples.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Amazon Music

- Amazon Alexa

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

Understanding Unconscious Bias

The human brain sometimes takes cognitive shortcuts to help make decisions, shortcuts that can lead to implicit or unconscious bias. Damien Meyer/AFP via Getty Images hide caption

The human brain sometimes takes cognitive shortcuts to help make decisions, shortcuts that can lead to implicit or unconscious bias.

The human brain can process 11 million bits of information every second. But our conscious minds can handle only 40 to 50 bits of information a second. So our brains sometimes take cognitive shortcuts that can lead to unconscious or implicit bias, with serious consequences for how we perceive and act toward other people.

Where does unconscious bias come from? How does it work in the brain and ultimately impact society?

Short Wave reporter Emily Kwong speaks with behavioral and data scientist Pragya Agarwal , author of Sway: Unravelling Unconscious Bias .

Email the show at [email protected] .

Buy Featured Book

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

This episode was produced by Rebecca Ramirez, fact-checked by Berly McCoy and edited by Viet Le.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

‘Could I really cut it?’

For this ring, I thee sue

Speech is never totally free

Mahzarin Banaji opened the symposium on Tuesday by recounting the “implicit association” experiments she had done at Yale and at Harvard. The final talk is today at 9 a.m.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Turning a light on our implicit biases

Brett Milano

Harvard Correspondent

Social psychologist details research at University-wide faculty seminar

Few people would readily admit that they’re biased when it comes to race, gender, age, class, or nationality. But virtually all of us have such biases, even if we aren’t consciously aware of them, according to Mahzarin Banaji, Cabot Professor of Social Ethics in the Department of Psychology, who studies implicit biases. The trick is figuring out what they are so that we can interfere with their influence on our behavior.

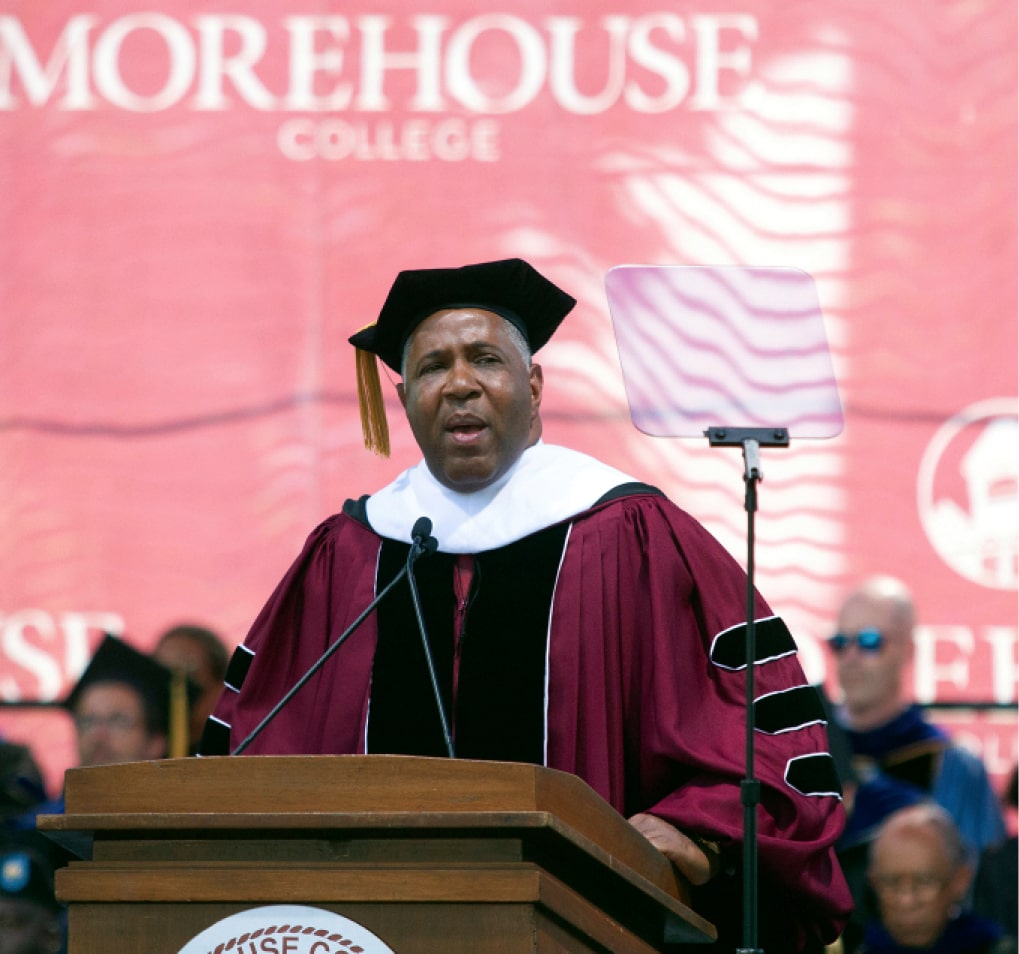

Banaji was the featured speaker at an online seminar Tuesday, “Blindspot: Hidden Biases of Good People,” which was also the title of Banaji’s 2013 book, written with Anthony Greenwald. The presentation was part of Harvard’s first-ever University-wide faculty seminar.

“Precipitated in part by the national reckoning over race, in the wake of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and others, the phrase ‘implicit bias’ has almost become a household word,” said moderator Judith Singer, Harvard’s senior vice provost for faculty development and diversity. Owing to the high interest on campus, Banaji was slated to present her talk on three different occasions, with the final one at 9 a.m. Thursday.

Banaji opened on Tuesday by recounting the “implicit association” experiments she had done at Yale and at Harvard. The assumptions underlying the research on implicit bias derive from well-established theories of learning and memory and the empirical results are derived from tasks that have their roots in experimental psychology and neuroscience. Banaji’s first experiments found, not surprisingly, that New Englanders associated good things with the Red Sox and bad things with the Yankees.

She then went further by replacing the sports teams with gay and straight, thin and fat, and Black and white. The responses were sometimes surprising: Shown a group of white and Asian faces, a test group at Yale associated the former more with American symbols though all the images were of U.S. citizens. In a further study, the faces of American-born celebrities of Asian descent were associated as less American than those of white celebrities who were in fact European. “This shows how discrepant our implicit bias is from even factual information,” she said.

How can an institution that is almost 400 years old not reveal a history of biases, Banaji said, citing President Charles Eliot’s words on Dexter Gate: “Depart to serve better thy country and thy kind” and asking the audience to think about what he may have meant by the last two words.

She cited Harvard’s current admission strategy of seeking geographic and economic diversity as examples of clear progress — if, as she said, “we are truly interested in bringing the best to Harvard.” She added, “We take these actions consciously, not because they are easy but because they are in our interest and in the interest of society.”

Moving beyond racial issues, Banaji suggested that we sometimes see only what we believe we should see. To illustrate she showed a video clip of a basketball game and asked the audience to count the number of passes between players. Then the psychologist pointed out that something else had occurred in the video — a woman with an umbrella had walked through — but most watchers failed to register it. “You watch the video with a set of expectations, one of which is that a woman with an umbrella will not walk through a basketball game. When the data contradicts an expectation, the data doesn’t always win.”

Expectations, based on experience, may create associations such as “Valley Girl Uptalk” is the equivalent of “not too bright.” But when a quirky way of speaking spreads to a large number of young people from certain generations, it stops being a useful guide. And yet, Banaji said, she has been caught in her dismissal of a great idea presented in uptalk. Banaji stressed that the appropriate course of action is not to ask the person to change the way she speaks but rather for her and other decision makers to know that using language and accents to judge ideas is something people at their own peril.

Banaji closed the talk with a personal story that showed how subtler biases work: She’d once turned down an interview because she had issues with the magazine for which the journalist worked.

The writer accepted this and mentioned she’d been at Yale when Banaji taught there. The professor then surprised herself by agreeing to the interview based on this fragment of shared history that ought not to have influenced her. She urged her colleagues to think about positive actions, such as helping that perpetuate the status quo.

“You and I don’t discriminate the way our ancestors did,” she said. “We don’t go around hurting people who are not members of our own group. We do it in a very civilized way: We discriminate by who we help. The question we should be asking is, ‘Where is my help landing? Is it landing on the most deserved, or just on the one I shared a ZIP code with for four years?’”

To subscribe to short educational modules that help to combat implicit biases, visit outsmartinghumanminds.org .

Share this article

You might like.

Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson discusses new memoir, ‘unlikely path’ from South Florida to Harvard to nation’s highest court

Unhappy suitor wants $70,000 engagement gift back. Now court must decide whether 1950s legal standard has outlived relevance.

Cass Sunstein suggests universities look to First Amendment as they struggle to craft rules in wake of disruptive protests

Harvard releases race data for Class of 2028

Cohort is first to be impacted by Supreme Court’s admissions ruling

Parkinson’s may take a ‘gut-first’ path

Damage to upper GI lining linked to future risk of Parkinson’s disease, says new study

High doses of Adderall may increase psychosis risk

Among those who take prescription amphetamines, 81% of cases of psychosis or mania could have been eliminated if they were not on the high dose, findings suggest

How Effective is Unconscious Bias Training? A comprehensive evaluation of recent assessments

Reviewed by Nick Spragg

A Review of

Unconscious Bias Training: An assessment of the evidence for effectiveness

Doyin Atewologun Tinu Cornish Fatima Tresh

If applicable, enter a short description here..

Introduction

Unconscious bias training: An assessment of the evidence for effectiveness by Doyin Atewologun, et al. is a literature review and meta-analysis of studies that examines the evidence for the effectiveness of unconscious bias training programs in actually reducing unconscious bias in individuals and organizations. The authors first define unconscious bias as the automatic and unintentional stereotypes, attitudes, and beliefs that people hold about particular groups of people. They argue that these biases can have negative effects on people’s behaviors and decision-making, leading to discrimination and inequality. To address this issue, many organizations have started to implement unconscious bias training (UBT) programs, which aim to increase awareness of these biases and reduce their influence.

UBT interventions target the automatic behavioral functions in the brain which employ heuristics, or mental short-cuts, to process the large amounts of information individuals receive quickly so that people can carry out tasks efficiently. These mental short cuts can reinforce negative social stereotypes, especially for women, ethnic minorities, differently abled individuals, neurodiverse individuals, and others with protected characteristics. Atewologun et al. reference a previous intervention carried out by Baroness McGregor-Smith, member of the UK House of Lords, entitled, “Race in the Workplace.” In the 2017 study, Mcgregor-Smith examined the deep structural and historical biases that prevented individuals with protected characteristics from progressing in their careers. Mcgregor-Smith recommended that the UK Government implement a free digital unconscious bias training resource, which became a widely utilized resource in both the UK public and private sectors. The authors reevaluate these interventions a year following their initial implementation.

Doyin Atewologun is the Dean of the Rhodes Scholarship at the University of Oxford and is an expert on diversity, leadership, organizational culture, and intersectionality. Tinu Cornish is an Occupational Psychologist who focuses on psychological approaches to diversity and inclusion leadership. Fatima Tresh is a psychologist and expert in human cognition and behavior addressing diversity, equity, and inclusion barriers.

Methods and Findings

Atewologun et al.’s assessment aims to achieve three objectives evaluating UBT program implementations across the UK: (1), to demonstrate evidence in favor of UBT’s effectiveness (2) to analyze the contextual conditions under which UBT is most effective; and (3), to highlight evidence gaps for further research. The authors underscore that “effectiveness” in this assessment is contingent on the aims of the training designer. A 3-part rapid evidence assessment methodology was utilized to assess the UBT’s effectiveness:

Identify evidence from online databases

- Published peer reviewed articles (N=57)

- Non-academic searches like reports (N=31)

Evaluate the quality of the evidence

- Utilize the Maryland Scale of Scientific Methods (ranking scale of 1-5: 1 exhibiting the lowest rigor (before-after comparison) 5 exhibiting the highest rigor (randomized control trial))

- Exclude sources with low scientific rigor (Level 1)

Analyze the evidence

- Identify aims and design of the intervention, draw conclusions about outcomes, and review the gathered evidence (N=18)

Among the key findings in the article, the authors highlight four types of UBT interventions they will measure: (1) awareness raising, (2) implicit bias change, (3) explicit bias change, and (4) behavior change.

Awareness Raising

Among the selected studies, eleven studies explicitly aimed to raise awareness of implicit bias, and the authors conclude in their analyses that UBT interventions can substantially increase awareness of bias. Whatley’s 2018 Implicit Association Test highlighted a successful intervention. In the study, Whatley measured UBT’s effectiveness on a multidisciplinary team’s attitudes toward African American students in special education. Whatley’s pre- and post- evaluations of a bias literacy workshop indicated the UBT intervention substantially improved both staff vulnerability to bias and individual student expectations.

Implicit Bias Change

Of the eleven studies aiming to change implicit bias, Atewologun et al. found that there is mixed evidence for UBT’s effectiveness. Two studies suggested that UBT can reduce the strength of bias; yet, there was no evidence that UBT can reduce bias to the extent of “neutral” preference. In Girod et al.’s 2016 evaluation of an educational presentation on reducing gender bias, 281 faculty members across 13 clinical departments at Stanford University indicated in the pre-trial a slight preference for males in leadership positions (this was consistent across all racial groups), and this male preference reduced in the post-trial measure. Yet, the authors concluded that males and older participants held stronger racialized and gendered implicit biases in both the pre- and post- trial measures.

Explicit Bias Change

Nine studies reviewed in the assessment indicated that UBT is effective in changing explicit bias, but less effective than awareness raising or implicit bias changing . Of the available research, it was unclear to the authors how to best measure explicit bias. In Moss-Racusin et al. ‘s 2016 “scientific diversity” workshop administered to 126 life sciences instructors, the aim of the study was to increase awareness of gender diversity, reduce gender bias, and increase diversity-promoting actions. In this particular study, all three aims were effectively achieved.

Behavior Change

Of the ten studies aiming to change behavior, only two of these studies actually measured behavior change Because of this limitation, the authors concluded that there is insufficient evidence to indicate UBT’s effectiveness. Research examining behavior change is limited, and methods evaluating behavior change have low validity because they do not measure actual observed behavior change. In Forscher’s 2017 UBT intervention administered to 292 United States university students, researchers found that the effects of unconscious bias awareness waned two weeks post-intervention. However, a follow-up study conducted two years later between the intervention group and a control group indicated possible long-term behavior change. Participants in the intervention group were more likely to publicly refute an essay endorsing racial stereotyping than the control group.

Conclusions

In the concluding remarks, the authors highlight a variety of high-level observations about the assessed literature. Among these observations, the most notable include:

- Male participants hold stronger unconscious gender biases than female participants. This gap can be reduced with UBT, and UBT may be more effective for men with respect to gender biases. There is some evidence that online and face-to-face UBT are equally effective for awareness raising.

- Mandatory UBT is generally more effective for behavior change than voluntary UBT. This is not supported by more rigorous studies, however.

- Bias reduction strategies are more effective for reducing implicit bias and ineffective in reducing explicit bias.

- Some mindfulness interventions can reduce implicit bias and possibly mitigate discriminatory actions.

- Bias mitigation strategies may have back-firing effects if participants do not want to be influenced or do not agree with the proposed direction of influence.

In the final remarks, the authors set forth a series of recommendations for practice and future research. The first recommendation is to have a more nuanced approach to UBT content: use an implicit association test to increase awareness of unconscious bias and measure changes in implicit bias, educate participants about unconscious bias theory, and integrate bias reduction strategies in the UBT to increase participant confidence in managing their biases. The second recommendation focuses on the UBT context, such as delivering training to those who work closely together in a team unit or otherwise. Finally, the third recommendation is to evaluate effectiveness: randomly assign matched participants to control and intervention groups and deliver training to control groups when effectiveness has been established.

The authors suggest multiple areas for further research: systematic comparisons of approaches and design characteristics, investigations of UBT’s effectiveness in reducing bias against all protected groups, uniform measurement outcomes of UBT, structural changes due to UBT interventions, additional cognitive or social processes integral to maintaining inequity, and the impact of mandatory versus voluntary attendance on UBT effectiveness.

- Training & Evaluation

- Training Evaluations

- explicit bias

- implicit bias

- organizational behavior

- Unconscious bias

- unconscious bias training

Share this Article

- Spragg, Nick

- Atewologun, Doyin

- Tinu Cornish

- Fatima Tresh

Related Articles

Antiracist school leadership: making ‘race’ count in leadership preparation and development.

Introduction Schools around the world have started to grapple more acutely with racism due to the changing needs of an increasingly racially diverse and integrated student population, as well as in response to urgent calls for educational reform. These calls particularly urge educational reforms that include to developing and growing an antiracist curriculum and trainings.…

Best Practices or Best Guesses? Assessing the Efficacy of Corporate Affirmative Action and Diversity Policies

Introduction Over the past several decades, there has been an increase in efforts to diversify the American corporate workforce. In 2018, the employment search engine Indeed saw an 18% increase in diversity and inclusion job postings from the previous year, and a 2017 report indicated that about $8 billion is spent annually on diversity training.…

Thank you for visiting RRAPP

Please help us improve the site by answering three short questions.

- Why did you visit or use the site today? Select an answer To lead DEI or racial equity efforts at my organization To advise leaders on DEI best practices at my organization To learn new strategies for antiracist organizational change For public policy purposes For general research purposes For academic research purposes For student assignment Out of curiosity Other

- How did you use the site today? Select an answer Find research materials Cite a RRAPP summary Cite an original article Share an article with a colleague or organization Share an article on social media Suggest an article for RRAPP to review and post An article or summary from RRAPP was shared with me Other

- Are you? Select an answer CEO/ED Senior management Staff Consultant Graduate Student Undergraduate Student Scholar/Researcher Other

- What industry are you in? Select an answer Academia Private Public/Government Non-profit Other

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplement Archive

- Editorial Commentaries

- Perspectives

- Cover Archive

- IDSA Journals

- Clinical Infectious Diseases

- Open Forum Infectious Diseases

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access

- Why Publish

- IDSA Journals Calls for Papers

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Advertising

- Reprints and ePrints

- Sponsored Supplements

- Branded Books

- Journals Career Network

- About The Journal of Infectious Diseases

- About the Infectious Diseases Society of America

- About the HIV Medicine Association

- IDSA COI Policy

- Editorial Board

- Self-Archiving Policy

- For Reviewers

- For Press Offices

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Unconscious bias—the role it plays and how to measure it, impact of bias on healthcare delivery, measuring bias—the implicit association test (iat), mitigating unconscious bias, call to action.

- < Previous

The Impact of Unconscious Bias in Healthcare: How to Recognize and Mitigate It

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Jasmine R Marcelin, Dawd S Siraj, Robert Victor, Shaila Kotadia, Yvonne A Maldonado, The Impact of Unconscious Bias in Healthcare: How to Recognize and Mitigate It, The Journal of Infectious Diseases , Volume 220, Issue Supplement_2, 15 September 2019, Pages S62–S73, https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiz214

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The increasing diversity in the US population is reflected in the patients who healthcare professionals treat. Unfortunately, this diversity is not always represented by the demographic characteristics of healthcare professionals themselves. Patients from underrepresented groups in the United States can experience the effects of unintentional cognitive (unconscious) biases that derive from cultural stereotypes in ways that perpetuate health inequities. Unconscious bias can also affect healthcare professionals in many ways, including patient-clinician interactions, hiring and promotion, and their own interprofessional interactions. The strategies described in this article can help us recognize and mitigate unconscious bias and can help create an equitable environment in healthcare, including the field of infectious diseases.

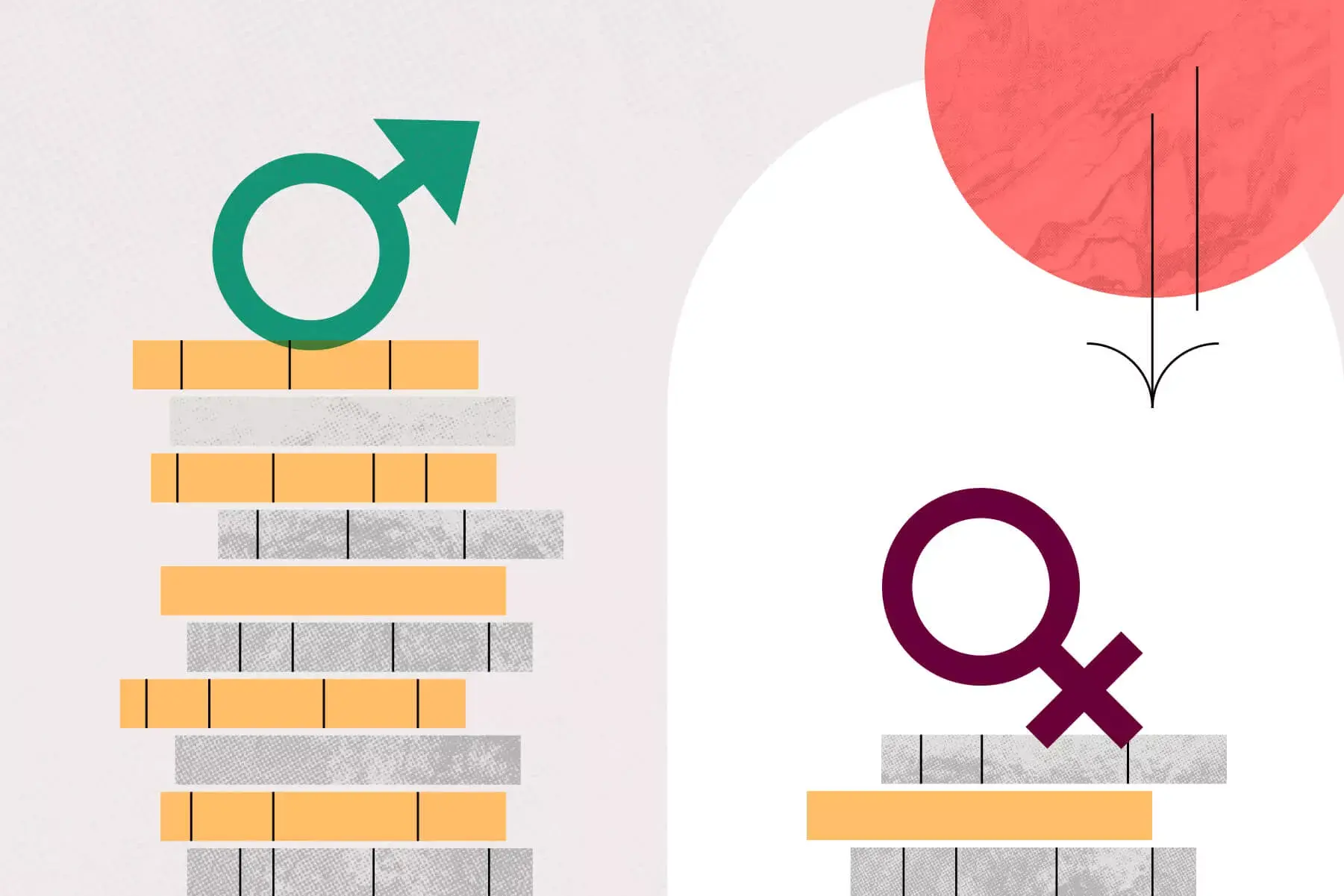

There is compelling evidence that increasing diversity in the healthcare workforce improves healthcare delivery, especially to underrepresented segments of the population [ 1 , 2 ]. Although we are familiar with the term “underrepresented minority” (URM), the Association of American Medical Colleges, has coined a similar term, which can be interchangeable: “Underrepresented in medicine means those racial and ethnic populations that are underrepresented in the medical profession relative to their numbers in the general population” [ 3 ]. However, this definition does not include other nonracial or ethnic groups that may be underrepresented in medicine, such as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or questioning/queer (LGBTQ) individuals or persons with disabilities. US census data estimate that the prevalence of African American and Hispanic individuals in the US population is 13% and 18%, respectively [ 4 ], while the prevalence of Americans identifying as LGBT was estimated by Gallup in 2017 to be about 4.5% [ 5 ]. Yet African American and Hispanic physicians account for a mere 6% and 5%, respectively, of medical school graduates, and account for 3% and 4%, respectively, of full-time medical school faculty [ 6 ]. As for LGBTQ medical graduates, the Association of American Medical Colleges does not report their prevalence [ 6 ]. Persons with disabilities are estimated to be 8.7% of the general population [ 4 ], while the prevalence of physicians with disabilities has been estimated to be a mere 2.7% [ 7 ]. Furthermore, although women currently outnumber men in first-year medical school classes [ 8 ], gender disparities still exist at higher ranks in women’s medical careers [ 9–11 ].

Unconscious or implicit bias describes associations or attitudes that reflexively alter our perceptions, thereby affecting behavior, interactions, and decision-making [ 12–14 ]. The Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) notes that bias, stereotyping, and prejudice may play an important role in persisting healthcare disparities and that addressing these issues should include recruiting more medical professionals from underrepresented communities [ 1 ]. Bias may unconsciously influence the way information about an individual is processed, leading to unintended disparities that have real consequences in medical school admissions, patient care, faculty hiring, promotion, and opportunities for growth ( Figure 1 ). Compared with heterosexual peers, LGBT populations experience disparities in physical and mental health outcomes [ 15 , 16 ]. Stigma and bias (both conscious and unconscious) projected by medical professionals toward the LGBTQ population play a major role in perpetuating these disparities [ 17 ]. Interventions on how to mitigate this bias that draw roots from race/ethnicity or gender bias literature can also be applied to bias toward gender/sexual minorities and other underrepresented groups in medicine.

Glossary of key terms.

The specialty of infectious diseases is not free from disparities. Of >11 000 members of the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), 41% identify as women, 4% identify as African American, 8% identify as Hispanic, and <1% identify as Native American or Pacific Islander (personal communication, Chris Busky, IDSA chief executive officer, 2019). However, IDSA data on members who identify as LGBTQ and members with disabilities are not available.

The 2017 IDSA annual compensation survey reports that women earn a lower income than men [ 18 ], and a review of the full report demonstrates similar disparities among URM physicians, compared with their white peers [ 19 ]. While it may not be feasible to assign a direct causal relationship between unconscious bias and disparities within the infectious diseases specialty, it is reasonable and ethical to attempt to address any potential relationship between the two. In this article, we define unconscious bias and describe its effect on healthcare professionals. We also provide strategies to identify and mitigate unconscious bias at an organizational and individual level, which can be applied in both academic and nonacademic settings.

Even in 2019, overt racism, misogyny, and transphobia/homophobia continue to influence current events. However, in the decades since the healthcare community has moved toward becoming more egalitarian, overt discrimination in medicine based on gender, race, ethnicity, or other factors have become less conspicuous. Nevertheless, unconscious bias still influences all human interactions [ 13 ]. The ability to rapidly categorize every person or thing we encounter is thought to be an evolutionary development to ensure survival; early ancestors needed to decide quickly whether a person, animal, or situation they encountered was likely to be friendly or dangerous [ 20 ]. Centuries later, these innate tendencies to categorize everything we encounter is a shortcut that our brains still use.

Stereotypes also inadvertently play a significant role in medical education ( Figure 1 ). Presentation of patients and clinical vignettes often begin with a patient’s age, presumed gender, and presumed racial identity. Automatic associations and mnemonics help medical students remember that, on examination, a black child with bone pain may have sickle-cell disease or a white child with recurrent respiratory infections may have cystic fibrosis. These learning associations may be based on true prevalence rates but may not apply to individual patients. Using stereotypes in this fashion may lead to premature closure and missed diagnoses, when clinicians fail to see their patients as more than their perceived demographic characteristics. In the beginning of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic, the high prevalence of HIV among gay men led to initial beliefs that the disease could not be transmitted beyond the gay community. This association hampered the recognition of the disease in women, children, heterosexual men, and blood donor recipients. Furthermore, the fact that white gay men were overrepresented in early reported prevalence data likely led to lack of recognition of the epidemic in communities of color, a fact that is crucial to the demographic characteristics of today’s epidemic. Today, there is still no clear solution to learning about the epidemiology of diseases without these imprecise associations, which can impact the rapidity of accurate diagnosis and therapy.

Unconscious bias describes associations or attitudes that unknowingly alter one’s perceptions and therefore often go unrecognized by the individual, whereas conscious bias is an explicit form of bias that is based on one’s discriminatory beliefs and values and can be targeted in nature [ 14 ]. While neither form of bias belongs in the healthcare profession, conscious bias actively goes against the very ethos of medical professionals to serve all human beings regardless of identity. Conscious bias has manifested itself in severe forms of abuse within the medical profession. One notable historical example being the Tuskegee syphilis study, in which black men were targeted to determine the effects of untreated, latent syphilis. The Tuskegee study demonstrated how conscious bias, in this case manifested in the form of racism, led to the unethical treatment of black men that continues to have long-lasting effects on health equity and justice in today’s society [ 21 ]. Given the intentional nature of conscious bias, a different set of tools and a greater length of time are likely required to change one’s attitudes and actions. Tackling unconscious bias involves willingness to alter one’s behaviors regardless of intent, when the impact of one’s biases are uncovered and addressed [ 22 ]

There is still debate, however, about the degree to which unconscious bias affects clinician decision-making. In one systematic review on the impact of unconscious bias on healthcare delivery, there was strong evidence demonstrating the prevalence of unconscious bias (encompassing race/ethnicity, gender, socioeconomic status, age, weight, persons living with HIV, disability, and persons who inject drugs) affecting clinical judgment and the behavior of physicians and nurses toward patients [ 12 ]. However, another systematic review found only moderate-quality evidence that unconscious racial bias affects clinical decision-making [ 23 ]. A detailed discussion of the impact of unconscious bias on healthcare delivery is out of the scope of this article, which is focused on the impact of unconscious bias as it relates to healthcare professionals themselves. Nevertheless, strategies to mitigate the effects of unconscious bias (discussed later) can be applied to healthcare delivery and patient interactions.

While we know that unconscious bias is ubiquitous, it can be difficult to know how much it affects a person’s daily interactions. In many cases, an individual’s unconscious beliefs may differ from their explicit actions. For example, healthcare professionals, if asked, might say they try to treat all patients equally and may not believe they hold negative attitudes about patients. However, by definition, they may lack awareness of their own potential unconscious biases, and their actions may unknowingly suggest that these biases are active.

To measure unconscious bias, Drs Mahzarin Banaji and Anthony Greenwald developed the IAT in 1998 [ 24 ]. Many versions of the IAT are accessible online (available at: https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/ ), but one of the most studied is the Race IAT. The IAT has been extensively studied as an inexpensive tool that provides feedback on an individual biases for self-reflection. The IAT calculates how quickly people associate different terms with each other. To determine unconscious race bias, the race IAT asks the subject to sort pictures (of white and black people) and words (good or bad) into pairs. For example, in one part of the Race IAT, participants must associate good words with white people and bad words with black people. In another part of the Race IAT, they must associate good words with black people and bad words with white people. Based on the reaction times needed to perform these tasks, the software calculates a bias score [ 20 , 24 ]. Category pairs that are unconsciously preferred are easier to sort (and therefore take less time) than those that are not [ 24 ]. These unconscious associations can be identified even in individuals who outwardly express egalitarian beliefs [ 20 , 24 ]. According to Project Implicit, the Race IAT has been taken >4 million times between 2002 and 2017, and 75% of test takers demonstrate an automatic white preference, meaning that most people (including a small group of black people) automatically associate white people with goodness and black people with badness [ 20 ]. Proponents of the IAT state that automatic preference for one group over another can signal potential discriminatory behavior even when the individuals with the automatic preference outwardly express egalitarian beliefs [ 20 ]. These preferences do not necessarily mean that an individual is prejudiced, which is associated with outward expressions of negative attitudes toward different social groups [ 20 ].

Many of the studies of unconscious bias described in this article use the IAT as the primary tool for measuring the phenomenon. Nevertheless, the degree to which the IAT predicts behavior is as of yet unclear, and it is important to recognize the limitations and criticisms of the IAT, as this is pertinent to its potential application in mitigating unconscious bias. Blanton et al reanalyzed data from 2 studies supporting the validity of the IAT, claiming that there is no evidence predicting individual behavior, with concerns for interjudge reliability and inclusion of outliers affecting results [ 25 ]. Response to this criticism by McConnell et al describes extensive training of test judges and evidence that the reanalysis was not a perfect replication of methods [ 26 ]. Blanton et al argue further in a different article that attempting to explain behavior on the basis of results of the IAT is problematic because the test relies on an arbitrary metric, leading to identified preferences when individuals are “behaviorally neutral” [ 27 ]. Notwithstanding the limitations of the IAT, none of its critics refute the existence of unconscious bias and that it can influence life experiences. The following sections review how unconscious bias affects different groups in the healthcare workforce.

Racial Bias

Medical school admissions committees serve as an important gatekeeper to address the significant disparities between racial and ethnic minorities in healthcare as compared to the general population. Yet one study demonstrated that members of a medical school admissions committee displayed significant unconscious white preference (especially among men and faculty members) despite acknowledging almost zero explicit white preference [ 28 ]. An earlier study of unconscious racial and social bias in medical students found unconscious white and upper-class preference on the IAT but no obvious unconscious preferences in students’ response to vignette-based patient assessments [ 29 ]. Unconscious bias affects the lived experiences of trainees, can potentially influence decisions to pursue certain specialties, and may lead to isolation. A recent study by Osseo-Asare et al described African American residents’ experiences of being only “one of a few” minority physicians; some major themes included discrimination, the presence of daily microaggressions, and the burden of being tasked as race/ethnic “ambassadors,” expected to speak on behalf of their demographic group [ 30 ].

Gender Bias

Gender bias in medical education and leadership development has been well documented [ 11 , 31 ]. Medical student evaluations vary depending on the gender of the student and even the evaluator [ 31 ]. Similar studies have demonstrated gender bias in qualitative evaluations of residents and letters of recommendations, with a more positive tone and use of agentic descriptors in evaluations of male residents as compared to female residents [ 11 ]. Studies evaluating inclusion of women as speakers have also demonstrated gender bias, with fewer women invited to speak at grand rounds [ 9 ] and differences in the formal introductions of female speakers as compared to male speakers [ 32 , 33 ], with men more likely referred to by their official titles than women.

Sexual and Gender Minority Bias

Sexual and gender minority groups are underrepresented in medicine and experience bias and microaggressions similar to those experience by racial and ethnic minorities. Experiences with or perceptions of bias lead to junior physicians not disclosing their sexual identity on the personal statement part of their residency applications for fear of application rejection or not disclosing that they are gay to colleagues and supervisors for fear of rejection or poor evaluations [ 34 ]. In one study, some physician survey respondents indicated some level of discomfort about people who are gay, transgender, or living with HIV being admitted to medical school. These respondents were less likely to refer patients to physician colleagues who were gay, transgender, or living with HIV [ 35 ]. These explicit biases were significantly reduced, compared with those revealed in prior surveys done in 1982 and 1999; opposition to gay medical school applicants went from 30% in 1982 to 0.4% in 2017, and discomfort with referring patients to gay physicians went from 46% in 1982 to 2% in 2017 [ 35 ]. The 2017 survey did not measure levels of unconscious bias, which is likely to still be pervasive despite decreased explicit bias. As with other types of bias, these data reveal that explicit bias against gay physicians has decreased over time; the degree of unconscious bias, however, likely persists. While this is encouraging to some degree, unconscious bias may be much more challenging to confront than explicit bias. Thus, members of underrepresented groups may be left wondering about the intentions of others and being labeled as “too sensitive.”

Studies including the perspectives of LGBTQ healthcare professionals demonstrate that major challenges to their academic careers persist to this day. These include lack of LGBTQ mentorship, poor recognition of scholarship opportunities, and noninclusive or even hostile institutional climates [ 36 ]. Phelan et al studied changes in biased attitudes toward sexual and gender minorities during medical school and found that reduced unconscious and explicit bias was associated with more-frequent and favorable interactions with LGBTQ students, faculty, residents, and patients [ 37 ].

Disability Bias

Physicians with disabilities constitute another minority group that may experience bias in medicine, and the degree to which they experience this may vary, depending on whether disabilities may be visible or invisible. One study estimated the prevalence of self-disclosed disability in US medical students to be 2.7% [ 7 ]. Medical schools are charged with complying with the Americans With Disabilities Act, but only a minority of schools support the full spectrum of accommodations for students with disabilities [ 38 ]. Many schools do not include a specific curriculum for disability awareness [ 39 ]. Physicians with disabilities have felt compelled to work twice as hard as their able-bodied peers for acceptance, struggled with stigma and microaggressions, and encountered institutional climates where they generally felt like they did not belong [ 40 ]. These are themes that are shared by individuals from racial and ethnic minorities.

A strategy to counter unconscious bias requires an intentional multidimensional approach and usually operates in tandem with strategies to increase diversity, inclusion, and equity [ 41 , 42 ]. This is becoming increasingly important in training programs in the various specialties, including infectious diseases. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education recently updated their common program requirements for fellowship programs and has stipulated that, effective July 2019, “[t]he program’s annual evaluation must include an assessment of the program’s efforts to recruit and retain a diverse workforce” [ 43 ]. The implication of this requirement is that recognition and mitigation of potential biases that may influence retention of a diverse workforce will ultimately be evaluated (directly or indirectly).

Mitigating unconscious bias and improving inclusivity is a long-term goal requiring constant attention and repetition and a combination of general strategies that can have a positive influence across all groups of people affected by bias [ 44 ]. These strategies can be implemented at organizational and individual levels and, in some cases, can overlap between the 2 domains ( Figure 2 ). In this section, we review how infectious diseases clinicians and organizations like IDSA and hospitals can use some of these strategies to address and mitigate implicit bias in our specialty.

Organization-level and personal-level strategies to mitigate unconscious bias. Orange circles indicate organization-specific strategies, green circles indicate individual-level strategies, and blue circles represent strategies that can be emphasized on both organizational and individual levels to mitigate implicit bias.

Organizational Strategies

Commitment to a culture of inclusion: more than just diversity training or cultural competency.

Creating change requires more than just a climate survey, a vision statement, or creation of a diversity committee [ 45 ]. Organizations must commit to a culture shift by building institutional capacity for change [ 41 , 46 ]. This involves reaffirming the need not only for the recruitment of a critical mass of underrepresented individuals, but equally importantly, the recruitment of critical actor leaders who take the role of change agents and have the power to create equitable environments [ 41 , 47–49 ]. These change agents need not themselves be underrepresented; indeed, the success of culture change requires the involvement of allies within the majority group (eg, men, white people, and cis-gender heterosexual individuals). IDSA has demonstrated a commitment to this type of culture change with recent changes in leadership structure and with intentional recruitment of individuals invested in diversity and inclusion; however, there is always room for reevaluation of other areas where diversity is desired.

Committing to a culture of inclusion at the academic-institution level involves creating a deliberate strategy for medical trainee admission and evaluation and faculty hiring, promotion, and retention. Capers et al describe strategies for achieving diversity through medical school admissions, many of which can also be applied to faculty hiring and promotion [ 49 ]. Notable strategies they suggest include having admissions (or hiring) committee members take the IAT and reflect on their own potential biases before they review applications or interview candidates [ 49 ]. They also recommend appointing women, minorities, and junior medical professionals (students or junior faculty) to admissions committees, emphasizing the importance of different perspectives and backgrounds [ 49 ]. Organizations can also survey employee perception of inclusivity. These assessments include questions on the degree to which an individual feels a sense of belonging within an institution, alongside questions pertaining to experiences of bias on the grounds of cultural or demographic factors [ 50 ]. Conducting regular assessments and analysis of survey results, particularly on how individuals of diverse backgrounds feel they can exist within the organization and their culture simultaneously, allows organizations to ensure that their trainings on unconscious bias and promotion of cultural humility lead to long-term positive change. Furthermore, realizing that different demographic groups may feel less respected than others provides information on areas of focus for consequent refresher seminars on combating unconscious bias in conjunction with cultural humility.

Meaningful Diversity Training and the Usefulness of the IAT

Notwithstanding potential criticisms of the IAT with respect to prediction of discriminatory behavior, this can be a useful tool within a comprehensive organizational training seminar directed toward understanding and addressing individual unconscious bias. In the study by Capers et al, over two thirds of admissions committee members who took the IAT and responded to the post-IAT survey felt positive about the potential value of this tool in reducing their unconscious bias [ 28 ]. Additionally, almost half were cognizant of their IAT results when interviewing for the next admissions cycle, and 21% maintained that knowledge of this bias affected their decisions in the next admissions cycle [ 28 ]. Perhaps this knowledge led to conscious changes in committee member behavior because, in the following year, the matriculating class was the most diverse in that institution’s history [ 28 , 49 ]. A similar bias education intervention coupled with the IAT led to a decreased unconscious gender leadership bias in one academic center [ 48 ]. IDSA and infectious diseases practices (or academic divisions) could consider ways to incorporate this into already established training for those in leadership roles or on leadership search committees.

Of course, the potential applicability of the IAT can be overstated—at best, several meta-analyses have demonstrated that there may only be a weak correlation between IAT scores and individual behavior [ 51–53 ], and several criticisms of the IAT have already been discussed here. Additionally, while important to acknowledge that bias is pervasive, care must be taken to avoid normalizing bias and stereotypes because this may have the unintended consequence of reinforcing them [ 54 ]. Important points that should be emphasized when using the IAT as part of diversity training include that (1) people should be aware of their own biases and reflect on their behaviors individually; (2) the IAT can suggest generally how groups of people with certain results may behave, rather than how each individual will behave; and (3) on its own, the IAT is not a sufficient tool to mitigate the effects of bias, because if there is to be any chance of success, an active cultural/behavioral change must be engaged in tandem with bias awareness and diversity training [ 55 ].

Individual Strategies

Deliberative reflection.

Before encounters that are likely to be affected by bias (such as trainee evaluations, letters of recommendation, feedback, interviews, committee decisions, and patient encounters), deliberative reflection can help an individual recognize their own potential for bias and correct for this [ 56 ]. It is also a good time to consider the perspective of the individual whom they will be evaluating or interacting with and the potential impact of their biases on that individual. Participants can be encouraged to evaluate how their own experiences and identities influence their interactions. Including data on lapses in proper care due to provider bias also proves helpful in giving workers real-life examples of the consequences of not being vigilant for bias [ 51 , 57 ]. This motivated self-regulation based on reflections of individual biases has been shown to reduce stereotype activation and application [ 44 , 58 ]. If one unintentionally behaves in a discriminatory manner, self-reflection and open discussion can help to repair relationships ( Figure 3 ).

Strategies to address personal bias before and after it occurs.

Question and Actively Counter Stereotypes

Individuals may question how they can actively counter stereotypes and bias in observed interactions. The active-bystander approach adapted from the Kirwan Institute [ 59 ] can provide insight into appropriate responses in these situations ( Figure 4 ).

Kirwan Institute approach to countering unconscious bias as an active bystander.

Strategies That Apply to Both Organizations and Individuals

Cultural competency and beyond: cultural humility.

Healthcare organizations seeking to develop providers who can work seamlessly with colleagues and more effectively treat patients from all cultural backgrounds have been conducting trainings in cultural competency [ 60 ]. The term “cultural competency” implies that one has achieved a static goal of championing inclusivity. This approach imparts a false sense of confidence in leaders and healthcare professionals and fails to recognize that our understanding of cultural barriers is continually growing and evolving [ 61 ]. Cultural humility has been proposed as an alternate approach, subsuming the teachings of cultural competency while steering participants toward a continuous path of discovery and respect during interactions with colleagues and patients of different cultural backgrounds [ 62 ]. Other synonymous terms include “cultural sensitivity” and “cultural curiosity.” Rather than checking a box for training, cultural humility focuses on the individual and teaches that developing one’s self-awareness is a critical step in achieving mindfulness for others [ 63 ]. Cultural humility emphasizes that individuals must acknowledge the experiential lens through which they view the world and that their view is not nearly as extensive, open, or dynamic as they might perceive [ 61 ]. By training leaders and healthcare professionals that they do not need to be and ultimately cannot be experts in all the intersecting cultures that they encounter, healthcare professionals can focus on a readiness to learn that can translate to greater confidence and willingness in caring for patients of varying backgrounds [ 61 ].

As cultural humility is important to recognizing and mitigating conscious and unconscious biases, patient simulations and diversity-related trainings should be augmented with discussions about cultural humility. By integrating cultural humility into healthcare training procedures, organizations can strive to eliminate the perceived unease healthcare professionals might experience when interacting with individuals from backgrounds or cultures unfamiliar to them. Cultural humility starts from a condition of empathy and proceeds through the asking of open questions in each interaction ( Figure 1 ). Instilling elements of cultural humility training within simulation-based learning provides participants with experience in treating a wide array of patients while providing low-risk, feedback-based learning opportunities [ 22 , 64 ].

Diversify Experiences to Provide Counterstereotypical Interactions

Exposing individuals to counterstereotypical experiences can have a positive impact on unconscious bias [ 10 , 44 , 55 ]. Therefore, intentional efforts to include faculty from underrepresented groups as preceptors, educators, and invited speakers can help reduce the unconscious associations of these responsibilities as unattainable. Capers et al suggest that including students, women, and African Americans and other racial and ethnic minorities on admissions committees may be part of a strategy to reduce unconscious bias in medical school admissions [ 49 ]. If institutions, organizations, and conference program committees are aware of their own metrics in this respect, following this information with deliberate choices to remedy inequities can have a profound impact on increasing diversity [ 65 ]. Furthermore, in medical training, while deliberate curricula involving disparities and care of underrepresented individuals are beneficial, educators must be aware of the impact of the hidden curriculum on their trainees. The term “hidden curriculum” refers to the aspects of medicine that are learned by trainees outside the traditional classroom/didactic instruction environment. It encompasses observed interactions, behaviors, and experiences often driven by unconscious and explicit bias and institutional climate [ 66–68 ]. Students can be taught to actively seek out the hidden curriculum in their training environment, reflect on the lessons, and use this reflection to inform their own behaviors [ 67 ]. Individuals can intentionally diversify their own circles, connecting with people from different backgrounds and experiences. This can include the occasionally awkward and uncomfortable introductions at professional meetings or at community events, making an effort to read books by diverse authors, or trying new foods with a colleague. These are small behavioral changes that, with time, can help to retrain our brain to classify people as “same” instead of “other.”

Mentorship and Sponsorship

Mentors can, at any stage in one’s career, provide advice and career assistance with collaborations, but sponsors are typically more senior individuals who can curate high-profile opportunities to support a junior person, often with potential personal or professional risk if that person does not meet expectations. URMs and women physicians tend not to have as much support with mentoring and sponsorship as the majority group, white men. Qualitative studies of URM physician perspectives typically reveal themes of isolation and lack of mentorship, regardless of the URM group being studied [ 30 , 36 , 69 ]. Possible reasons include lack of mentors from similar backgrounds or ineffective mentoring in discordant mentor-mentee relationships. Mentor-training workshops that intentionally include unconscious bias training can enhance the effectiveness of mentors working with diverse trainees and junior faculty and address this potential barrier to URM success [ 70 ]. Providing mentorship within an individual department, as well as support for participating in external mentorship and career development programs, can help create sponsorship opportunities that eventually influence career advancement [ 41 ]. Many professional societies such as IDSA provide mentorship opportunities, and these can be enhanced by encouraging more sponsorship of junior clinicians for opportunities such as podium lectures, moderating at conferences, writing editorials, or committee positions.

In the years since the IAT was first described, researchers have published countless data on the impact of unconscious bias. Fortunately, explicit and implicit attitudes toward many disenfranchised groups of people have regressed to a more neutral position over time [ 71 ], but this does not mean that unconscious bias has disappeared. Just as healthcare providers are required to stay up to date on medical techniques and procedures to best serve their patients, we propose that trainings involving the social aspects of medicine be treated similarly. Cultural humility is characterized by lifelong learning and is a key aspect of a successful provider-patient relationship. Thus, it is imperative that healthcare organizations and professional medical societies such as IDSA continually provide healthcare professionals with learning opportunities to enhance their interactions with individuals different from themselves. Effectively addressing unconscious bias and subsequent disparities in IDSA will need comprehensive, multifaceted, and evidence-based interventions ( Figure 5 ).

Unconscious bias highlights.

IDSA has demonstrated a commitment to diversifying its society leadership by commissioning the Gender Disparities Task Force and the Inclusion, Diversity, Access & Equity Task Force, reconfiguring existing committees, developing new committees (eg, the Leadership Development Committee), and creating new opportunities, such as the IDSA Leadership Institute. While these are important and impactful actions, we propose the following additional steps to address the role of unconscious bias in various settings. First, develop an IDSA-sponsored climate survey to assess perceptions of inclusion and belonging within the Society, and repeat this climate assessment after implementing bias reduction strategies. Second, provide IDSA-sponsored education/training on unconscious bias reduction strategies and cultural humility to academic infectious disease divisions and fellowship programs to support the recruitment and retention of a diverse infectious diseases physician workforce. Third, develop benchmarks for excellence in infectious diseases divisions and fellowship training programs to evaluate these bias reduction strategies. Fourth, provide education/training on unconscious bias–reduction strategies and cultural humility to leadership and membership within IDSA. Specifically, the board of directors, the Leadership Development Committee, the Awards Committee, and others involved in electing, nominating, or honoring members should consider including incorporating the IAT and bias-reduction education for their committee members. After implementing such strategies, IDSA should reevaluate metrics of awardees, committee chairs, and leadership to determine whether these strategies made an impact. Fifth, cultivate existing mentorship programs within IDSA, with the added focus of intentional mentoring and sponsorship of groups traditionally underrepresented in leadership. Sixth, commit to consistent review and revision of infectious diseases recruitment messaging, ensuring that materials and media counter harmful stereotypes and represent true diversity. Seventh, collect, review, and publish metrics of diversity in all facets of the membership, including IDWeek speaker demographic characteristics, IDSA journal editor/reviewers, guideline authorship, and committee membership, with intentional response strategies to change these demographic characteristics to a more diverse distribution. Eighth, be transparent about reporting of metrics, with clear accountability and flexibility to adjust initiatives based on results.

Although there are numerous data describing the impact of unconscious bias on healthcare delivery, clinician-patient interactions, and patient outcomes, discussion of these aspects is out of the scope of this article, which focuses on the impact of unconscious bias on healthcare professionals. Additionally, the majority of data on unconscious bias presented in this article relates to general academic training and career development, as data in the infectious diseases practice community is limited. This represents an area of need for evaluation within the specialty of infectious diseases, since a vast majority of members are in clinical practice and may experience bias in varying degrees. While it is important to support trainees who may experience unconscious bias, it is also critical to provide support for infectious diseases clinicians further along in their careers, as a means to maintain retention in the specialty. Finally, some individuals may prefer person-first language, while others may prefer identity-first language when referring to disabilities. We consistently used person-first language throughout this manuscript based on the recommendation by the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention ( https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/disabilityandhealth/pdf/disabilityposter_photos.pdf ).

Supplement sponsorship . This supplement is sponsored by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Acknowledgments . We thank Drs Molly Carnes, Ranna Parekh, and Arghavan Salles, as well as Lena Tenney, for critical review of this manuscript before publication; Mr Chris Busky, for providing written communications about the demographic characteristics of IDSA membership and leadership; and Catherine Hiller, for her assistance with manuscript preparation.

J. R. M. wrote first draft and subsequent revisions; D. S. and R. V. contributed to the first draft and subsequent revisions; S. K. contributed to the first draft and subsequent revisions; Y. A. M. contributed to subsequent revisions; and all authors reviewed a final version of the work before submission.

Potential conflicts of interest . J. R. M. and D. S. are members of the IDSA Inclusion, Diversity, Access & Equity Task Force. All other authors report no potential conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.