Your Trusted Advisors for Admissions Success

Admissions and test prep resources to help you get into your dream schools

2024 Medical School Personal Statement Ultimate Guide (220+ Examples)

220+ medical school personal statement examples, plus a step-by-step guide to writing a unique essay and an analysis of a top-5 medical school personal statement.

Part 1: Introduction to the medical school personal statement

Part 2: a step-by-step approach to writing an amazing medical school personal statement, part 3: in-depth analysis of a top-5 medical school personal statement, part 4: unique vs. clichéd medical school personal statements: 10 key differences, appendix: medical school personal statement examples.

You probably know someone who achieved a solid GPA and MCAT score , conducted research, shadowed physicians, engaged in meaningful volunteer work, and met all the other medical school requirements , yet still got rejected by every school they applied to.

You may have even heard of someone who was rejected by over 30 medical schools or who was shut out by every program two years in a row, despite doing “all the right things.”

It’s also common to come across people who have incredibly high stats (e.g., a 3.8 GPA and a 518 MCAT score) but didn’t get into a top-10 or top-20 medical school.

With stories like these and the scary statistic that over 60% of medical school applicants do not matriculate into medical school in any given year , it’s hard not to be anxious about the admissions process and wonder how you’ll ever get into medical school .

We bet you’ve puzzled over why so many qualified applicants are rejected beyond the fact that there are too few spots. After all, you’ve noticed how some applicants receive many interview invitations and acceptances, whereas others receive few or none.

The main reason why many qualified applicants are rejected from every med school—or significantly underperform expectations based on their admissions profile—is that they do not stand out on their application essays.

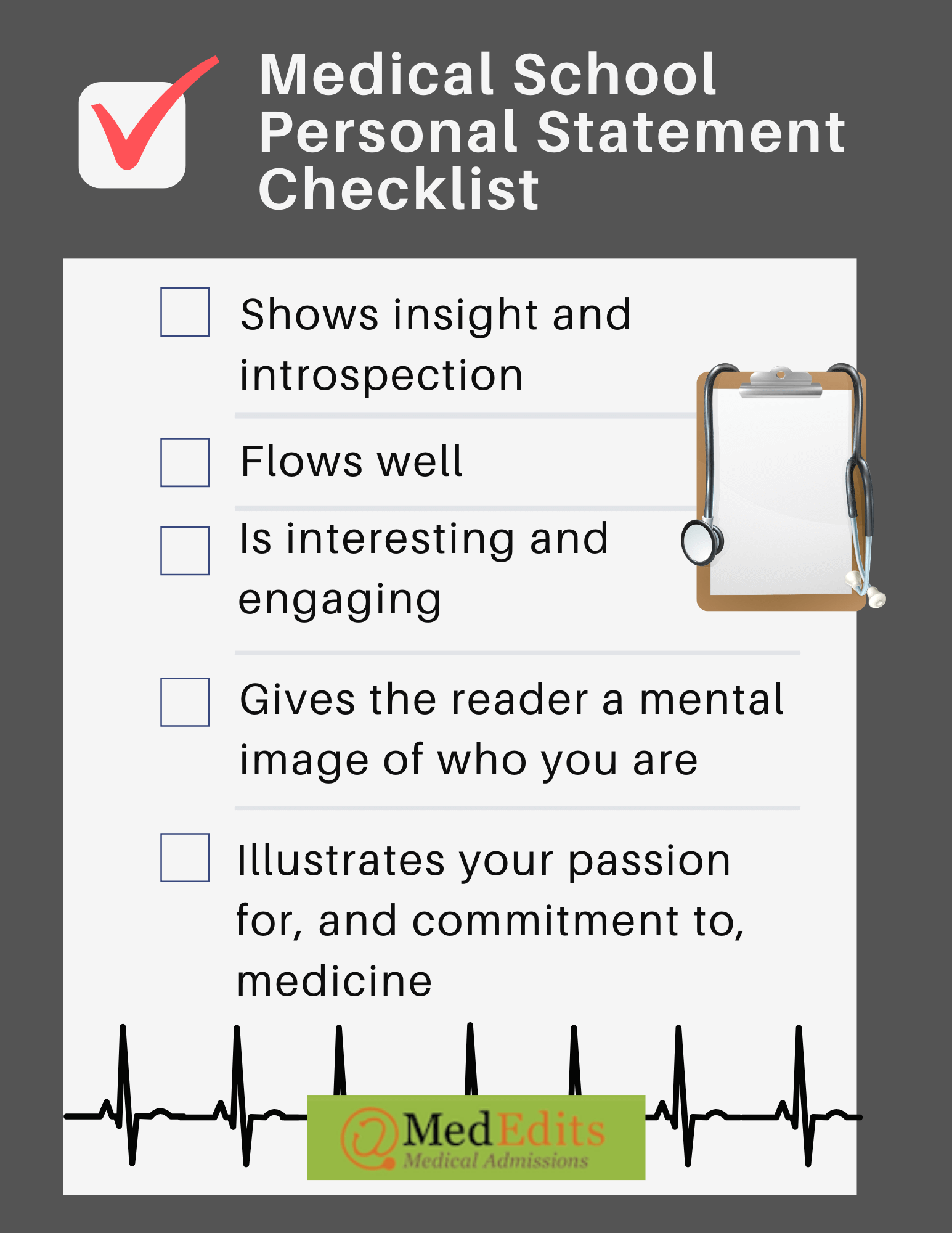

While the need to stand out holds true for every piece of written material on your applications, your personal statement is the single most important essay you will have to write during your admissions process. It’s especially important to get right because it allows you to show admissions committees how your story sets you apart among other qualified candidates (i.e., your competition). Moreover, the quality of your personal statement has a significant influence on your admissions success.

Of course, this means that writing a great medical school personal statement comes with a lot of pressure.

Gain instant access to the most in-depth personal statement resources available so you can write an essay that stands out. Subscribe today to lock in the current investments, which will soon increase for new subscribers. (Note: You can end your subscription at any time and retain access to the content through the end of the period for which you signed up.)

Medical school personal statement challenges and opportunities

As you prepare to write, you’re probably concerned about:

Choosing the “right” topic

Making sure your essay is unique and not clichéd

Your essay clearly highlighting why you want to go into medicine

Whether it’s what admissions committees are looking for

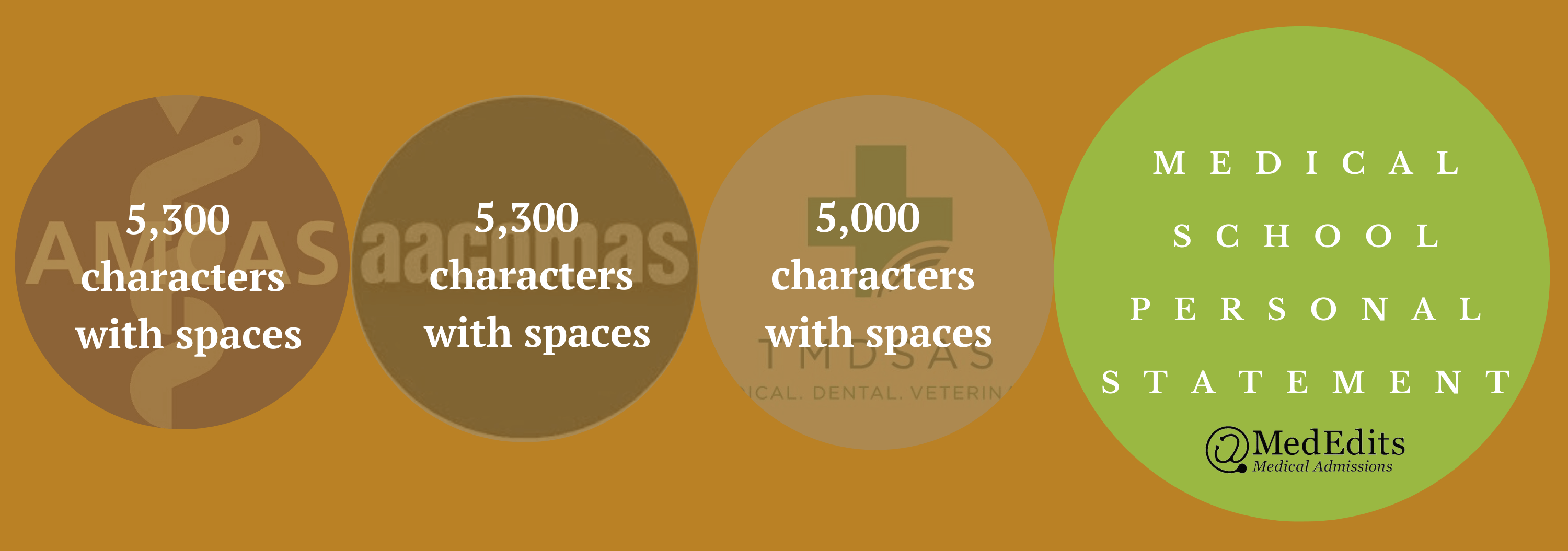

The good news is that the AMCAS personal statement prompt—“Use the space provided to explain why you want to go to medical school”—is intentionally vague and gives you the opportunity to write about anything you want in up to 5,300 characters (including spaces). If you’re wondering how many words 5,300 characters comes out to, it roughly corresponds to 500 words or 1.5 single-spaced pages.

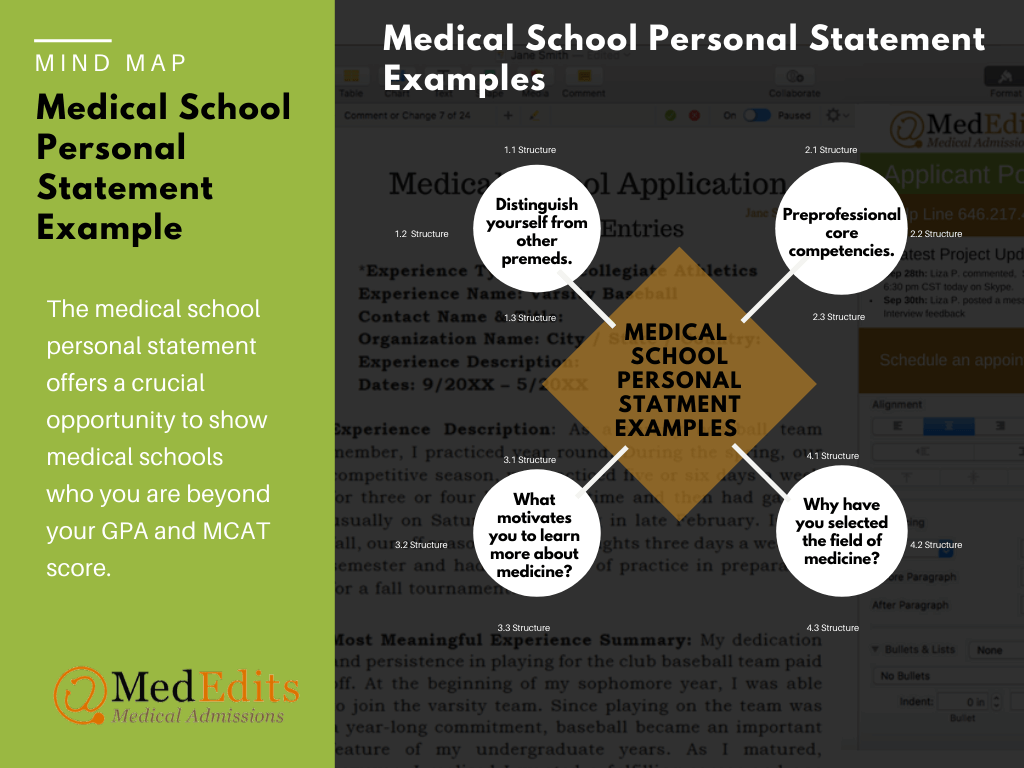

In other words, you have complete control over how you show admissions committees the following:

Who you are beyond your numbers and your resume (i.e., why you? )

The reasons you want to go into medicine (i.e., why medicine? )

Struggling to write your med school personal statement?

Get our free 102-page guide to help you with every step, including additional exclusive personal statement examples .

100% privacy. No spam. Ever.

Thank you! Your guide is on its way. In the meantime, please let us know how we can help you crack the the medical school admissions code . You can also learn more about our 1-on-1 medical school admissions support here .

Medical school personal statement character limits

Remember that admissions committees want to accept people , not just a collection of GPAs, MCAT scores, and premed extracurricular activities. Your personal statement and other written materials must therefore clearly highlight the specific qualities and experiences that would make you an excellent physician.

If your essay does this, you’ll have a leg up on other applicants. On the other hand, a clichéd personal statement will bore admissions readers and consequently make them less interested in admitting you.

Put another way, your personal statement is your best opportunity to stand out—or to look like everyone else who reads tons of sample essays, tries to “play it safe” with boring anecdotes, and ends up in the rejection pile.

What this personal statement guide covers

As you begin drafting your essay, you might find yourself perusing countless medical school personal statement examples online, at your college’s premed counseling office, or from friends who applied to med school a year or two ago. But remember that the sample personal statements you find on Student Doctor Network, Reddit , premed blogs, or at your college’s pre-health advising center are the same ones that everyone else is looking at and attempting to imitate!

To help you avoid common pitfalls and write a memorable personal statement, we wrote a comprehensive guide to help you get one step closer to earning your white coat rather than having to reapply to med school .

At a high level, this guide covers the following:

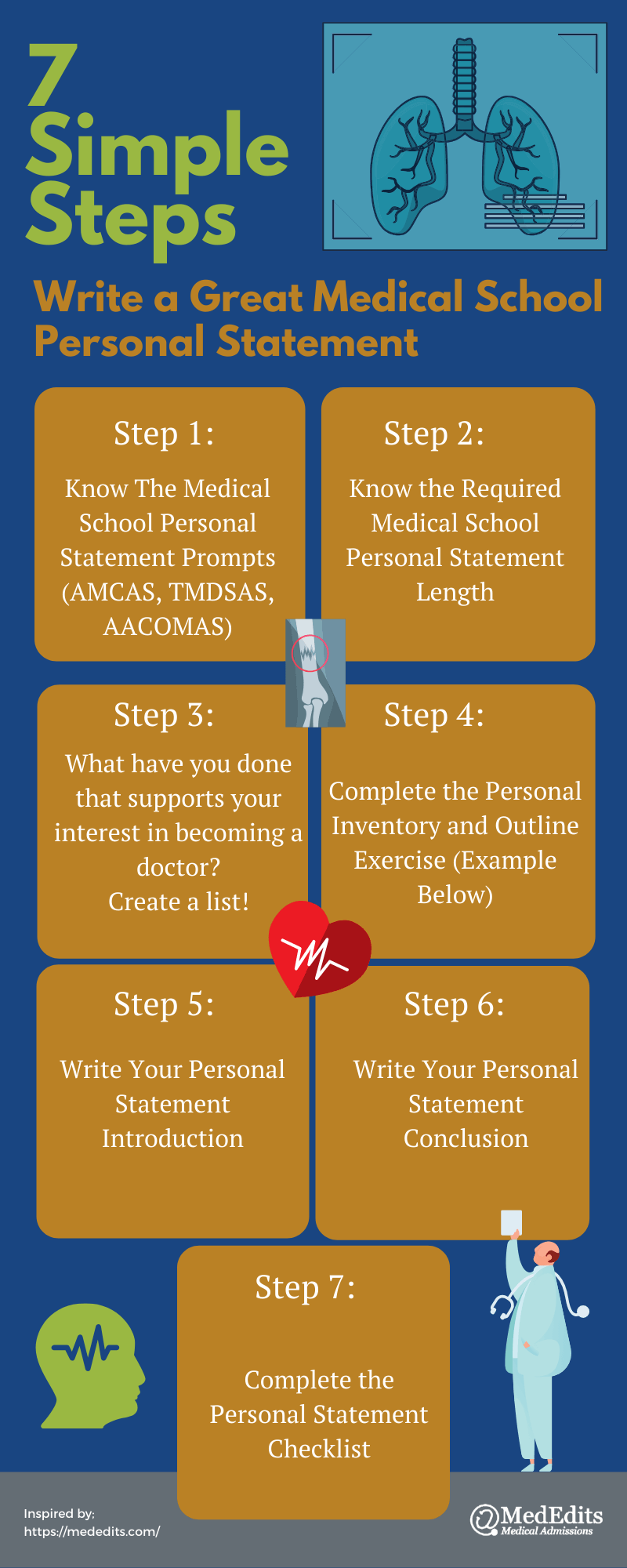

A step-by-step approach to producing a standout personal statement (Part 2)

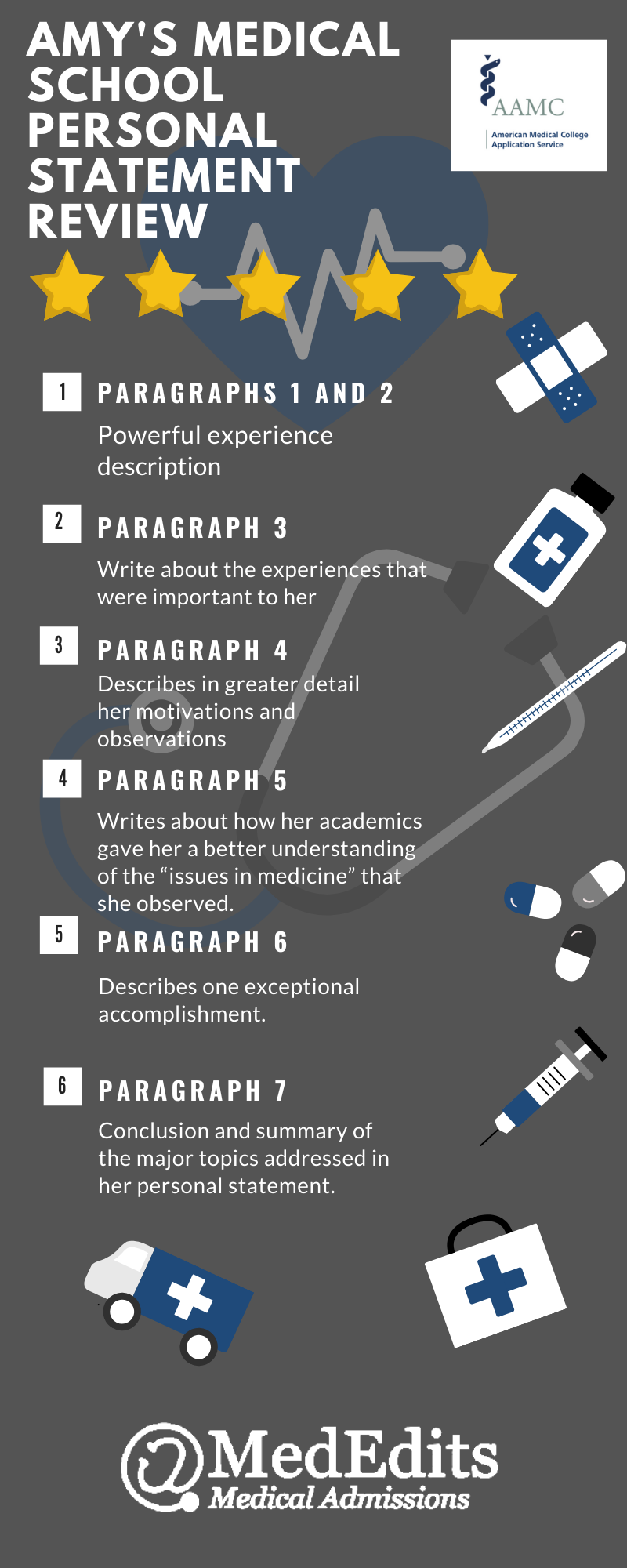

A paragraph-by-paragraph analysis of a top-5 personal statement (Part 3)

Key differences that separate unique vs. clichéd personal statements (Part 4)

Medical school personal statement examples (Appendix)

Upon reviewing this guide, you’ll have all the information you need to go from having no topic ideas to producing a personal, meaningful, and polished essay. Throughout the guide, you’ll also come across various “special sections” that address common questions and concerns we’ve received from applicants over the years.

And if you’re left with lingering questions about how to write a personal statement for medical school, just submit them in the comments section at the end of the guide so we can answer them, usually within 24 hours.

Without further ado, it’s time to begin the writing process.

When should I begin to write my med school personal statement?

The earliest we recommend you begin working on your personal statement is fall of your junior year. That way, even if you decide to go to med school straight through (i.e., without taking a gap year or two), you will have completed a bulk of the extracurriculars that you will cover on your application and will also have an essay that describes your current thoughts and feelings about medicine. But regardless of whether you apply straight through or apply post-undergrad, it’s a good idea to begin working on your personal statement during the fall or winter preceding your application cycle (e.g., start writing your essay between September 2023 and January 2024 if you intend to apply during the 2024-2025 application cycle) so that you have plenty of time to write a great essay and can take full advantage of rolling admissions by submitting your primary application early.

Before writing, the typical applicant does two things:

Pulls up their resume and attempts to identify the experience that is “most unique” or “most authentic”

Searches for essay sample after essay sample, hoping to be inspired by someone else’s writing

Eventually, students begin to read every sample essay they can get their hands on, hoping that consuming countless examples will give them the “aha moment” they need to produce their own personal statement.

Here’s the problem: Without understanding why an essay is strong, you risk producing a cliché essay based on some “template” you came across.

With this “template approach,” you’ll risk making your essay sound like someone else’s, which is a sure-fire way of producing a clunky or clichéd essay. This is precisely why we included the numerous sample medical school personal statement essays at the end of this guide.

We also don’t believe that reviewing your CV or thinking through your personal experiences to identify the “most unique” topic ideas is a valuable approach to brainstorming your personal statement. This “resume-first” approach tends to lead to writing an introduction that may not communicate your intended message, especially because it might not flow with the remainder of your experiences.

So, what should your personal statement include? Over the years, our students have found the most success by taking our “qualities-first” approach—thinking through the impression they want to leave on adcoms and then selecting the experiences that best highlight those qualities.

The myth of the "perfect topic"

Every topic can lead to a standout or average personal statement, depending on how compellingly you write it. In other words, there's no such thing as a "good" or "bad" essay topic, only strong or weak execution. Many students delay working on their personal statement until they discover the “perfect topic,” but no such topic exists. We’ve read incredible essays and weak essays on pretty much every topic. What mattered was how the writer linked the topic with their personal path to medicine. We should reinforce a point mentioned in passing in the previous paragraph: pretty much every medical school personal statement topic has been used at this point. You can stand out by sharing your personal stories, unique insights, and eye-opening experiences, not by writing about a brand-new topic, as so few exist.

How to write a great personal statement introduction (Goal: Engage the reader)

Before you begin to write, we recommend that you:

Develop a list of qualities you want to demonstrate; and

Think of events or situations that highlight these qualities.

Then , you should write about one of these events or situations in a way that demonstrates these qualities and captures the reader’s attention.

Does my personal statement need to have a "hook"?

The short answer: Yes. But as with most things related to medical school admissions, the answer is more complicated. A "hook" is a sentence or story, typically presented in the opening paragraph, intended to grab the reader's attention. Because adcoms read tons of applications each year, it's important that they're engaged from the start. Otherwise, it's very likely that they will discount the remainder of your personal statement and your odds of getting into their school will drop precipitously. Unfortunately, many medical school applicants go overboard and force a dramatic story in hopes of presenting a hook—a trauma they observed in the ER, an emotional moment with a patient, and so on. The story might be marginally associated with the rest of their essay but will largely be viewed as a cheap way to capture attention. To be clear, there is nothing inherently wrong with discussing a difficult medical counter, personal difficulty, or any other particular type of story. However, your selection must be associated with the qualities you want to demonstrate across your entire essay and serve as its foundation. In addition, your hook need not be your opening sentence. It could be the entire first paragraph, a cliffhanger at the end of your opening paragraph, or even a second paragraph that was set up by the first. The goal is simply to ensure that you're engaging your reader early and setting the tone for the remainder of your essay.

Step 1: List your greatest qualities.

To answer the personal statement prompt more easily, focus again on the question of what you want admissions committees to know about you beyond your numbers and achievements.

We’re not talking about your hobbies (e.g., “I followed Taylor Swift to every concert she performed in the U.S. during this past year”), although you could certainly point to aspects of your lifestyle in your essay to make your point.

Instead, we’re talking about which of your qualities –character, personality traits, attitudes–you want to demonstrate. Examples include:

Extraordinary compassion

Willingness to learn

Great listening skills

Knowledge-seeking

Persistence

And so on. If you have difficulty thinking of your great qualities (many students do), ask family members or close friends what you’re good at and why they like you. It might be awkward, but this exercise really helps because others tend to view us very differently from how we view ourselves.

Finally, choose the two or three qualities that you want to focus on in your personal statement. Let’s use compassion and knowledge-seeking as the foundational qualities of an original example for this guide.

We cannot overstate how important it is to think of the qualities you want to demonstrate in your personal statement before choosing a situation or event to write about. Students who decide on an event or situation first usually struggle to fit in their qualities within the confines of their story. This is one of the biggest medical school personal statement mistakes we see students make.

On the other hand, students who choose the qualities they want to convey first are easily able to demonstrate them because the event or situation they settle on naturally highlights these qualities.

I listed several qualities I can demonstrate, but I'm not sure which to choose. Can you say more?

Your personal statement represents just one part of your much larger application. You'll have opportunities to demonstrate several of your great qualities through your AMCAS Work and Activities section, your secondary essays, and even your interviews. Therefore, any two or three qualities you want to convey through your personal statement will work; don't stress about figuring out the "perfect" ones, as no such thing exists. And when in doubt, ask family members and friends.

Step 2: When or where have you demonstrated these qualities?

Now that we’re off our soapbox and you’ve chosen qualities to highlight, it’s time to list any event(s) or setting(s) where you’ve demonstrated them.

We should explicitly mention that this event or setting doesn't need to come from a clinical experience (e.g., shadowing a physician , interacting with a young adult patient at a cancer center, working with children in an international clinic) or a research experience (e.g., making a major finding in cancer research during your gap year ), although it’s okay if it involves an extracurricular activity directly related to medicine.

In fact, since most students start their essays by describing clinical or research experiences, starting off with something else–travel (e.g., a camping trip in Yellowstone), volunteering (e.g., building homes in New Orleans), family (e.g., spending time with and learning from your elderly and ill grandmother back home in New Hampshire), work (e.g., helping out at your parents’ donut shop)–can help you immediately stand out.

Let’s start with the example of building homes in New Orleans. Why? Because we could easily demonstrate compassion and knowledge-seeking through this experience. Notice how the qualities we select can choose the story for us?

Step 3: Describe your event as a story.

Here’s where the art of writing a great personal statement really comes in.

Admissions officers read thousands of essays, most of which are very clichéd or dry. Therefore, it’s critical that you stand out by engaging the reader from the very beginning. The best way by far to capture admissions officers’ attention early is by developing a story about the event or situation you chose in Step 2 at the start of your essay.

Keep in mind, however, that the same event can be written about in a boring or engaging way. Therefore, the story or topic you choose is less important than how you pull it off.

Let’s look at an actual example of how the same event can be described in a routine vs. compelling manner:

One of my most eye-opening experiences came when I volunteered with Habitat for Humanity in New Orleans during the summer months of 2014. Up to that point, I had only heard about the destruction caused by Hurricane Katrina nine years earlier. Although pictures and stories of the aftermath compelled me to volunteer, it was not until I observed the emotional pounding the people of New Orleans had experienced that I developed a greater sense of compassion for their plight.

Compelling:

New Orleans was hot and humid during the summer months of 2014–no surprise there. However, for a native Oregonian like me, waking up to 90-degree and 85%-humidity days initially seemed like too much to bear. That was until I reflected on the fact that my temporary discomfort was minute in contrast to the destruction of communities and emotional pounding experienced by the people of New Orleans during and after Hurricane Katrina nine years earlier. Although pictures and stories of the aftermath compelled me to understand its effects on the community and volunteer, actually building homes and interacting with the locals, like nine-year-old Jermaine, who cried as I held his hand while we unveiled his rebuilt home, taught me that caring for people was as much about lifting spirits as making physical improvements.

Many people may feel the routine example is pretty good. Upon closer look, however, it seems that:

The focus is as much on New Orleanians as the applicant

The story is not particularly relatable (unless the reader had also volunteered there)

There isn’t much support for the writer actually being touched by the people there

On the other hand, the compelling example:

Keeps the spotlight on the applicant throughout (e.g., references being from Oregon, discusses her reflections, interacting with Jermaine)

Has a relatable plot (e.g., temporary discomfort, changing perspectives)

Is authentic (e.g., provides an example of how she lifted spirits)

Does my essay need to have an “aha moment,” that is, the moment when I decided to become a doctor? I’ve noticed that so many medical school personal statement examples include one.

Your essay does not need to include an “aha moment.” In fact, many of the best med school personal statements we’ve read do not include such a moment. Students who believe they need to mention an “aha moment” in their personal statement are typically falling into the trap of writing what they believe the reader wants. But frankly, the reader simply wants to learn about your personal and professional path to medicine. We’ve polled many students over the years about whether they had an experience that immediately switched them on to medicine. Our findings indicate that only 10 percent of students have experienced a moment where they knew they wanted to become a doctor and never looked back. The other 90 percent either knew they wanted to become a physician since childhood, had a growing interest in medicine over years, or came to the realization during or after college.

Step 4: Demonstrate your qualities.

(Note: This section applies to all aspects of your essay.)

“Show, don’t tell” is one of the most common pieces of advice given for writing personal statements, but further guidance or examples are rarely provided to demonstrate what it looks like when done well.

This is unfortunate because the best way to understand how standout personal statements demonstrate qualities through an engaging story is by reading two examples of the same situation: one that “tells” about a quality, and another that “shows” a quality.

Let’s revisit the last sentence of each story example we provided in the previous section to better understand this distinction.

Telling (from the routine story):

…it was not until I observed the emotional pounding the people of New Orleans had experienced that I developed a greater sense of compassion for their plight.

Showing (from the compelling story):

…actually building homes and interacting with the locals, like 9 year-old Jermaine, who cried as I held his hand while we unveiled his rebuilt home, taught me that caring for people…

Notice how the second example demonstrates compassion without ever mentioning the word “compassion” (hence no bolded words)? Moreover, the same sentence demonstrates knowledge-seeking:

Although pictures and stories of the aftermath compelled me to understand its effects on the community and volunteer, actually building homes and interacting with the locals ...

That’s what you’re going for.

Think about it. Whom do you consider to be more kind:

A person who says, “I’m really nice!”; or

A person who you've observed doing nice things for others?

Clearly, the second person will be viewed as more kind, even if there's no real-world difference between their levels of kindness. Therefore, by demonstrating your qualities, you will come across as more impressive and authentic to admissions committees.

Is it ever okay to tell in a medical school personal statement?

Telling, rather than showing, is okay in your first couple of drafts so that you get something on paper. The purpose of engaging in a robust revision process is to help you chisel out the main ideas you wish to convey and communicate them in the most effective way possible. Furthermore, telling is sometimes the most efficient way to convey certain information. For example, background information about people or situations in your essay can be told as this will move the narrative along and save valuable characters. However, if your final draft is full of instances of telling instead of showing, you likely haven’t thought through your experiences enough. Showing demonstrates a robust thought process that the writer has gone through and signals to adcoms this is an intelligent and thoughtful applicant who can bring a substantial amount of value to their institution, not to mention the profession of medicine itself. Further, showing generally makes for a more engaging and memorable reading experience. Sensory details and personal anecdotes will be more memorable for adcoms than general statements.

Over 90% of our students get into med school—the first time.

Get our free 102-page guide to help you with every step of the admissions process, from writing great essays and choosing the right schools to acing interviews.

How to write strong personal statement body paragraphs (Goal: Describe your path to medicine)

After writing your opening paragraph to engage the reader, it’s time to write the meat and potatoes of your personal statement. Specifically, it’s time to discuss experiences that helped you grow and led to you to pursue medicine.

What should be avoided in a medical school personal statement?

Put differently, "What should you not talk about in your personal statement?" There are no specific topics that you should definitely avoid in your essay. Unfortunately, you will hear many people tell you not to bring up certain things—a parent who is a physician, a physical health or mental health condition, sports participation, volunteering abroad, etc. However, all of these anecdotes or topics can be the foundation for strong personal statements as well as weak ones; what matters is your writing approach.

Step 5: Discuss your most formative experiences that led you to medicine.

Return to your list from Step 2 (When or where have you demonstrated these qualities?) and choose one to three more experiences/areas (e.g., research, clinical work) that led you to medicine.

Why choose no more than four experiences total?

Because you should be aiming for depth over breadth (remember, you’re working with a 5,300-character limit for both AMCAS (MD application) and AACOMAS (DO application). Rather than discuss everything you’ve done, apply the following five-step formula to expand on key experiences in the body paragraphs of your personal statement:

Discuss why you pursued the experience

Mention how you felt during the experience

Describe what you accomplished and learned

Discuss how your experience affected you and the world around you

Describe how the experience influenced your decision to pursue medicine

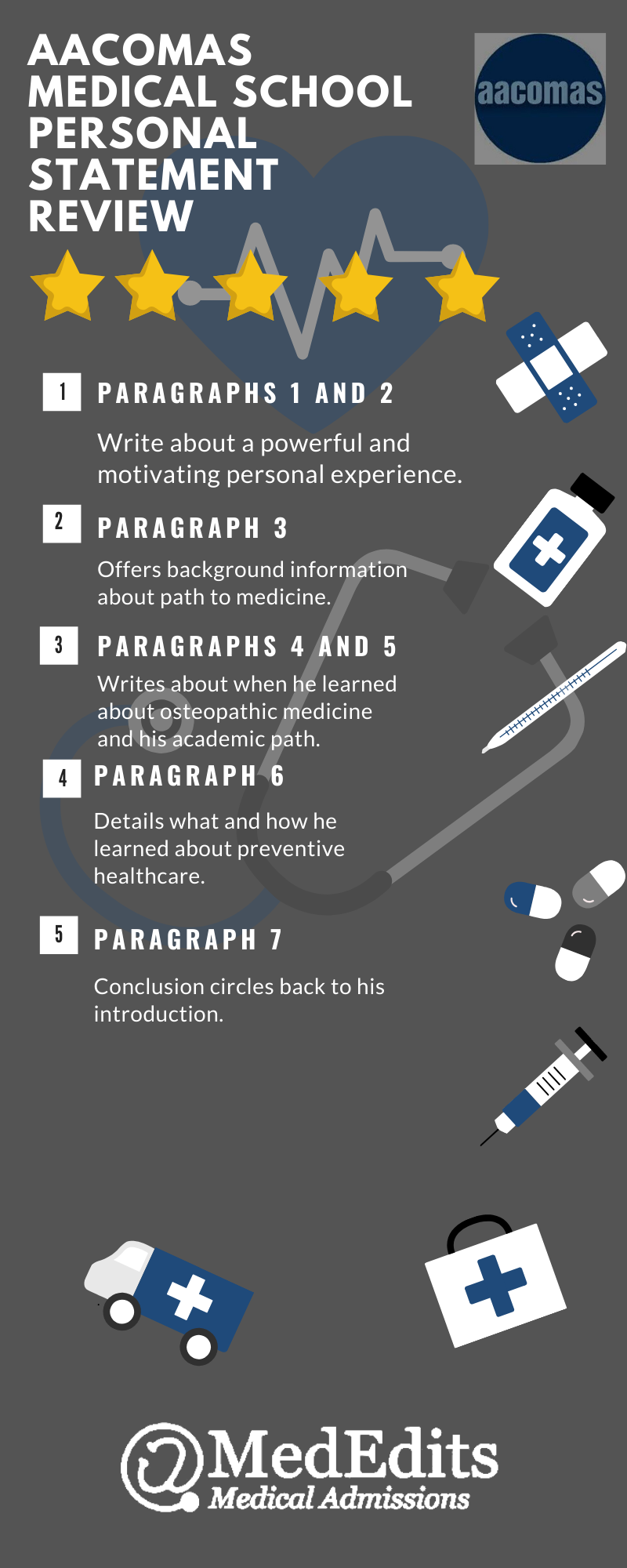

Does the guidance in this resource apply to DO personal statements as well?

Yes, for the most part. We cover similarities and differences between AMCAS and AACOMAS personal statements in detail in our MD vs. DO guide . The general themes and writing styles of your personal statement can be similar if you’re applying to both types of schools. Also, since 2019, AACOMAS increased the length of personal statements they will accept to match AMCAS at 5,300 characters. The biggest difference between the two will be how you target the underlying philosophies of the practice of medicine in your essay. You know that osteopathic medicine uses a more holistic approach, so you’ll have to rethink your essay to better appeal to adcoms at a DO school.

Below are two examples–one routine and one compelling–to demonstrate how to achieve this:

Shadowing the neurosurgeons at Massachusetts General Hospital and witnessing their unwavering dedication to their patients and patients’ families helped me realize that I wanted to make a similar impact on people's lives.

This sentence doesn't answer the “Why medicine?” question (for example, you could greatly impact people's lives through law or teaching), nor does it demonstrate your qualities (although it makes the neurosurgeons look really good).

I was initially frustrated while shadowing neurosurgeons and caring for patients (e.g., conversing with them during downtime and providing anything in my power to make them comfortable, such as extra pillows, water, or snacks) at Massachusetts General Hospital because many patients recovered very slowly–and sometimes not at all. I wondered whether these experiences would deter me from pursuing medicine. Therefore, I was surprised when the opposite occurred. The physicians’ unwavering dedication to their patients and families' expressed gratitude–even in their saddest days–provided more than enough confirmation that medicine was the path I should pursue to make a similar physical and emotional impact on people's lives.

By going deeper about an experience, this example allowed the student to convey:

How they felt (“I was initially frustrated while shadowing…”)

How they were affected (“…the opposite [of determent] occurred”)

How they were influenced to pursue medicine specifically

Collectively, the student demonstrated their compassion, personal growth, and desire to pursue medicine.

(Note: Discuss your formative experiences in the body paragraphs in chronological order, as long as it doesn’t disrupt your essay’s flow. For example, if you choose to write about one experience in 2014 and another in 2013, write about your 2013 experience first, even if you wrote about the 2014 experience in your introductory paragraph. Having a clear timeline makes it easier for the reader to follow along.)

How many experiences should I cover in my personal statement?

If you’re like most students, you should cover somewhere between three and four personal or professional experiences in your personal statement. Beyond four, and you risk covering too much and not achieving sufficient depth; your essay might read like a narrative. Fewer than three, and your experience descriptions might get too wordy. That said, every essay is different, so you might be able to write a fantastic personal statement with fewer than three experiences or more than four. In fact, one of the best personal statements we’ve ever helped a student produce focused on a single 24-hour time period that spanned two separate experiences.

How to write a memorable medical school personal statement conclusion (Goal: Tie it all together)

It’s (almost) time to end your personal statement and move on!

The concluding paragraph should highlight three things:

Your positive qualities (you can mention them explicitly here rather than “show” them)

Perspectives gained from your formative experiences

Your passion for medicine

Additionally, the best essays somehow refer to their introductory paragraph’s story to “close the loop.”

Step 6: Reemphasize your qualities, perspectives, and passions.

Focusing on experiences in your introduction and body paragraphs that convey your greatest qualities helps you develop a consistent theme throughout your essay. It also makes closing your essay much easier.

To demonstrate this, we’ll show you how New Orleans volunteering and neurosurgery shadowing can be tied together to reemphasize compassion and knowledge-seeking, highlight perspectives gained, and communicate a strong desire to pursue medicine.

The consistent theme throughout my extracurricular work is that, whereas I initially pursue experiences–clinical, volunteer, or otherwise–to learn, what sticks with me even more than newfound knowledge is the compassion I develop for the people I serve. Furthermore, I have realized that there is a multitude of ways to serve, such as treating people’s physical ailments, offering empathy for anxious family members, or leaving my comfort zone to help a struggling community. These perspectives, coupled with my lifelong fascination with the human body’s complexities, leave no doubt that medicine is the path through which I want to use my abilities to make a positive holistic impact on people’s lives. I hope 9-year-old Jermaine knows that I was equally touched by his gratitude for a rebuilt home, and how his reaction was partly responsible for me devoting my career to help others feel the way he did on that hot and muggy summer day.

Let’s see whether this concluding paragraph checks all three boxes:

Positive qualities (“knowledge-seeking” and “compassion,”): check

Perspectives gained from formative experiences (“…realized that there is a multitude of ways to serve”): check

Passion for medicine (“medicine is the path through which I want to use my abilities to make a positive holistic impact on people’s lives”): check

This paragraph also gets bonus points for looping Jermaine in one final time.

Essay conquered.

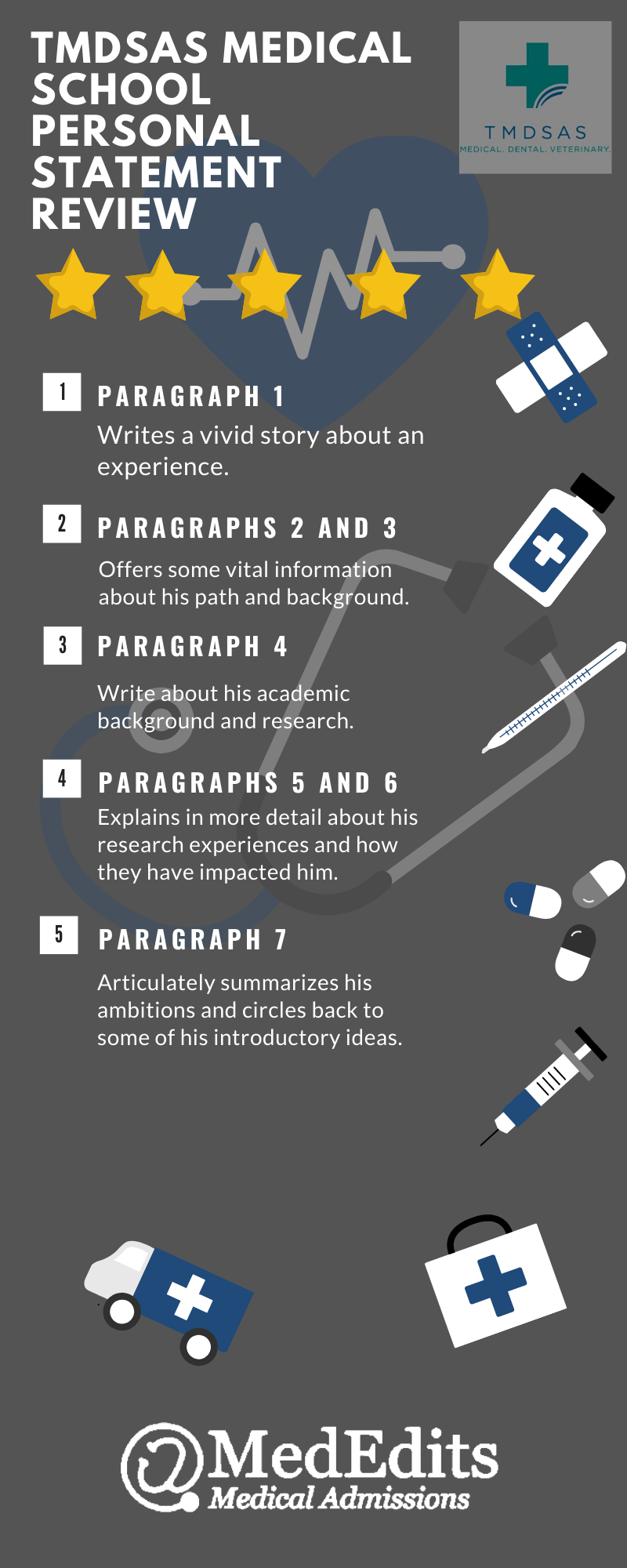

Does the guidance in this resource apply to TMDSAS personal statements as well?

Yes, though the TMDSAS personal statement offers a 5000-character limit vs. 5300 characters for AMCAS and AACOMAS. You can learn more about the Texas medical school application by reading our TMDSAS guide , which includes examples of a successful personal statement, personal characteristics essay, and optional essay.

Final thoughts

Your medical school personal statement offers a unique opportunity to share your story and describe your path to medicine–however you want to.

Rather than dive right in and list the extracurricular experiences that you think will most impress admissions committees, consider what impression you want to leave them with. In other words, which of your qualities do you want to be remembered for?

Once you've identified your defining qualities, the task of communicating why you are specifically fit for medicine becomes much easier. Through engaging stories, you can leave no doubt in readers' minds that you're not only qualified for this field, but also the right person for the job.

If you've ever read an article or forum post offering “tips” on how to write a great medical school personal statement, you've probably been given clichéd advice with very little supporting information, like:

“Be yourself”

“Offer a unique angle”

“Show, don’t tell”

“Get personal”

“Don’t use clichés”

“Be interesting”

“Check for grammar and spelling errors”

And so on. Here’s what usually happens when you read tips like these: You understand the information, but you’re still stuck in the same place you were before reading the article. You continue to stare at the blank document on your computer, hoping you’ll have an “aha moment.”

Unfortunately, “aha moments” rarely, if ever, come. Much more typically, students procrastinate and/or end up writing about extracurricular and personal experiences that they think admissions committees (adcoms) will be impressed by.

The problem is that if you don’t get your personal statement right, you can compromise your entire application.

If you’re a high-achieving applicant with a strong GPA , MCAT score , and rich extracurricular activities , you may get into less desirable schools than you’d hoped. If you’re an applicant on the borderline, you may not get in at all.

On the other hand, writing a powerful medical school personal statement provides adcoms insights into who you are as a person and as a budding physician. More importantly, it helps maximize your odds of admission in an increasingly competitive process.

We want you to be part of this latter group so that you can get into the best schools possible. Therefore, we figured it would be valuable to share a paragraph-by-paragraph analysis of a medical school personal statement that helped one of our students get into their dream school, which also happens to be ranked in the top 5 of the U.S. News & World Report Best Medical Schools rankings.

Throughout the analysis, we apply our internal essay evaluation framework, QPUD , which stands for the following:

You can apply the QPUD framework to analyze your own writing. You’ll soon learn that the best personal statements aren’t produced by accident, but rather through multiple thoughtful iterations.

Struggling to write your med school application essays?

Enter your name and email below to receive additional med school personal statement examples that aren’t available elsewhere.

Full-length medical school personal statement with analysis

Before we get into the weeds with our analysis, we encourage you to read the personal statement example in its entirety. As you go through it, you should keep the following questions in mind:

Does the applicant demonstrate qualities that are desirable in a physician? If so, which ones?

Is the personal statement mostly about the applicant, or other people?

Could anyone else have written this personal statement, or is it unique to the applicant?

Does the personal statement cover too much, or is there real depth ?

Here’s the personal statement sample:

Sure, it was a little more crowded, cluttered, and low-tech, but Mr. Jackson’s biology classroom at David Starr Jordan High School in South Los Angeles seemed a lot like the one in which I first learned about intermolecular forces and equilibrium constants. Subconsciously, I just assumed teaching the 11th graders about the workings of the cardiovascular system would go smoothly. Therefore, I was shocked when in my four-student group, I could only get Nate’s attention; Cameron kept texting, Mercedes wouldn’t end her FaceTime call, and Juanita was repeatedly distracted by her friends. After unsuccessfully pleading for the group’s attention a few times, I realized the students weren’t wholly responsible for the disconnect. Perhaps the problem was one of engagement rather than a lack of interest since their focus waned when I started using terminology—like vena cava—that was probably gibberish to them. So, I drew a basic square diagram broken into quarters for the heart and a smiley face for the body’s cells that needed oxygen and nutrients. I left out structure names to focus on how four distinct chambers kept the oxygenated and deoxygenated blood separate, prompting my students with questions like, “What happens after the smiley face takes the oxygen?” This approach enabled my students to draw conclusions themselves. We spent much of class time going through the figure-8 loop, but their leaning over the table to see the diagram more clearly and blurting out answers demonstrated their engagement and fundamental understanding of the heart as a machine. My elation was obvious when they remembered it the following week.

Ever since my middle school robotics days when a surgeon invited us to LAC+USC Medical Center to unwrap Tootsie rolls with the da Vinci surgical system, I’ve felt that a physician’s role goes beyond serving patients and families. I feel an additional responsibility to serve as a role model to younger students—especially teenagers—who may be intrigued by STEM fields and medicine. Furthermore, my experience in Mr. Jackson’s classroom demonstrated the substantial benefits of assessing specific individuals’ needs even when it requires diverging slightly from the structured plan. Being flexible to discover how to best engage my students, in some ways, parallels the problem-solving aspect I love about medicine.

Clinical experiences go even further by beautifully merging this curiosity-satisfying side of medicine with what I feel is most fulfilling: the human side of care provision. My experience with a tiny three-year-old boy and his mother in genetics clinic confirmed the importance of the latter. Not only was I excited to meet him because he presented with a rare condition, but also because he and his chromosomal deletion had been the focus of my recent clinical case report, published in Genetics in Medicine. While researching his dysmorphic features and disabilities, other patients with similar deletions, and the possible genes contributing to his symptoms, I stayed up until 4 AM for several weeks, too engrossed to sleep. What was more exciting than learning about the underlying science, however, was learning about the opportunity to meet the boy and his mother in person and share my findings with them.

As soon as I walked into the examination room, I noticed the mother avoiding eye contact with the genetic counselor while clutching her son to her chest. I sensed her anxiety and disinterest in hearing about my research conclusions. The impact of her son’s condition on their daily lives probably transcended the scientific details in my report. So despite my desire to get into the science, I restrained myself from overwhelming her. Instead, I asked her to share details about the wonderful interventions she had procured for her son—speech and physical therapy, sign language lessons, special feeds, etc. Through our conversations, I realized that she was really looking for reassurance—for doing a great job caring for her son. I validated her efforts and offered relief that there were other families navigating similar difficulties. As the appointment progressed, I observed her gradually relaxing. Rather than feel weighed down by the research findings I was eager to get off my chest, I felt light as well.

At the end of the appointment, the mom offered to let me hold her son, who gazed back at me with his bright blue eyes. While cradling the little boy humanized the medical details, the mother’s gesture displayed profound trust. Above all, this experience allowed me to recognize that interactions between a patient plus family and their doctor are more than intermediary vehicles to treatment; they are critical and beneficial in their own right. Learning this affirmed my longstanding desire and eagerness to become a physician. While research is essential and will surely always trigger my curiosity, I want my work to transcend the lab bench. Specifically, I want to continue engaging with patients and helping them through life’s difficult moments—with physical treatment and genuine support. And since working with each patient constitutes an entirely different experience, I know my medical career will never cease to be fulfilling.

(Word count: 835; Character count: 5,223)

What if some of the experiences I choose to write about in my essay aren't directly related to medicine?

No worries. Medical school admissions committees look to admit individuals with qualities befitting good doctors. These qualities can be demonstrated through experiences directly related to medicine, as well as through experiences that seemingly have little to do with medicine but cast a very positive light on you. That said, your personal statement should include at least one experience directly related to medicine. In your essay, you'll want to briefly describe how your interest in medicine developed, followed by how you consistently pursued that interest.

Now, let’s analyze the entire personal statement paragraph by paragraph and answer the questions posed above.

Paragraph 1

The applicant does a great job of engaging the reader. While reading the paragraph, it’s easy to get transported to the classroom setting they describe due to the level of detail provided. (e.g., “crowded, cluttered, and low-tech,” “Cameron kept texting, Mercedes wouldn’t end her FaceTime call…,” “leaning over the table”) The applicant also highlights their service work in the community, and hints that the school may be in an underserved part of town.

The applicant contrasts the chaotic, distracted classroom with the attention and enthusiasm students exhibit after their educational intervention. This “transformation” reflects positively on the applicant because it demonstrates that they can get creative in addressing a difficult situation.

At this point, we don’t yet know about the applicant’s passion for medicine, but we learn about their interest in biology, teaching, serving, and working directly with people. All of these activities can be pursued through medicine, so the transition to medicine later in their personal statement can be seamless.

Q: Does the applicant demonstrate qualities that are desirable in a physician? If so, which ones?

Patient, assumes responsibility, flexible (e.g., “I realized the students weren’t wholly responsible for the disconnect. Perhaps the problem was one of engagement rather than a lack of interest since their focus waned when I started using terminology—like vena cava—that was probably gibberish to them. So, I drew a basic square diagram…”)

Commitment to helping students/people learn and understand (e.g., “prompting my students with questions…,” “My elation was obvious when they remembered it the following week.”)

P: Is the paragraph mostly about the applicant, or other people?

While the applicant discusses others in the introduction (e.g., the 11th graders, Nate, Juanita), there’s no question that they are the primary and most interesting character in the paragraph.

U: Could anyone else have written this paragraph, or is it unique to the applicant?

Although all competitive applicants participate in service work—many within schools—the writer makes this paragraph their own by doing the following:

Including highly specific details about the setting, environment, and students

Describing their thoughts, insights, and emotions whenever possible

D: Does the paragraph cover too much, or is there real depth?

This paragraph is a model of depth. The applicant describes how they taught a single biology lesson during a single class period at a single school. It doesn’t get much more focused than that.

Does my personal statement's introduction paragraph story have to be about an experience during college or beyond?

Not necessarily. That said, if you write your introduction about an earlier-than-college experience, you'll want to quickly transition to your college and post-college years. While medical schools want to learn about your most formative experiences, they really want to know about who you are today.

Paragraph 2

The applicant effectively uses the second paragraph to provide context, about their early interest in medicine and in mentoring youth. It becomes clear, therefore, why the applicant started off their essay writing about a teaching experience in an 11th-grade classroom.

In addition, the applicant quickly transitions from a non-medical service experience to introduce reasons behind their interest in medicine. For example, the applicant describes how they intend to serve patients and families through the field, as well as scratch their own problem-solving itch to help people.

Another important piece to highlight is how the applicant uses showing vs. telling differently across the first two paragraphs. Whereas the introductory paragraph primarily shows qualities (e.g., “So, I drew a basic square diagram…”), the second paragraph primarily tells (e.g., “Being flexible to discover how to best engage my students…”).

Because the applicant proved their flexibility in the introduction (i.e., by showing it), they can claim to be flexible here (i.e., by telling it). On the other hand, if the applicant called themselves flexible from the outset without providing evidence, they may have come across as arrogant or unobservant.

Beyond describing their early interest in medicine (i.e., “Ever since my middle school robotics days when a surgeon invited us to LAC+USC Medical Center…” there is little demonstration of qualities here. Nevertheless, the goals for this paragraph—transition to medicine, describe at a high level what draws them to medicine, set up later stories about problem solving—are clearly achieved.

The second paragraph highlights hypothetical individuals (e.g., patients and families, specific individuals) to describe the applicant’s medical interests.

Between the early experience observing the da Vinci surgical system and continuing the discussion of Mr. Jackson’s classroom, it would be very difficult for another applicant to convincingly replicate this paragraph.

The applicant certainly covers more experiences here than in the intro, but they do so to bridge the service discussion with the upcoming discussion of medical experiences. Notice also how this paragraph is intentionally kept short. The goal isn’t to get too deep into their middle school experiences, or to do more telling than necessary. Make the transition and move on so you can achieve more depth later.

Does my med school personal statement need to discuss a challenge I experienced?

It’s a common misconception to think that you have to highlight some major adversity to sound impressive. It’s true that some students have experienced greater challenges than others and their process of overcoming those challenges has led them to develop qualities befitting a great doctor. But what matters is your ability to discuss your commitment to becoming a physician and the insights you developed about your place in the medical field via personal and extracurricular experiences.

Paragraph 3

The third paragraph immediately builds off of the preceding one by letting the reader know that even more fulfilling than satisfying their own curiosity (and problem solving) is providing care to real people. This is a very important disclosure because the reader may be wondering what the applicant’s primary motivation is. As a medical school applicant, you must convey a “people first” attitude.

The applicant then dives right into what sounds like a fascinating research experience that not only results in a publication (to be discussed further in their AMCAS Work and Activities section ), but also leads to actually meeting the patient with the rare genetic condition. The applicant’s approach clearly integrates their passion for research and clinical work.

The paragraph also ends with a strong “hook.” The admissions reader is left wondering how the meeting with the boy and his mother went, so they will continue to read attentively.

Curious and hard-working (e.g., “While researching his dysmorphic features and disabilities, other patients with similar deletions, and the possible genes contributing to his symptoms, I stayed up until 4 AM for several weeks, too engrossed to sleep”)

Accomplished (e.g., “my recent clinical case report, published in Genetics in Medicine .”)

Once again, the applicant does a masterful job of incorporating storytelling and other characters (i.e., the boy and his mother) to convey the qualities that will make them a great doctor. In other words, this paragraph isn’t really about the boy and his mother, but rather how the applicant prepped for their meeting with them.

Between the upcoming meeting with the three-year-old boy and his mother, researching the boy’s genetic condition, and getting published in a specific journal, it’s basically impossible to replicate this paragraph.

The applicant maintains focus on how their interest in service and research can be applied to help real people. They take it one step further by highlighting a specific time when they did just that. There is no additional fluff, tangential information, or competing storylines.

How do you write a hook for a medical school personal statement?

Tomes could be written discussing this very topic. The best way to hook a reader in your personal statement is to open with something interesting and engaging. A good hook will leave an emotional impression on them, thereby implanting your narrative in their memory. Of course, this is easier said than done. Writing a good hook is tricky because you want to strike the right balance between intriguing and naturally engaging. You can leave an emotional impression without being overly dramatic. Too much drama and your hook risks sounding forced which will diminish your essay’s effectiveness. You may end up “standing out” but for the wrong reasons. To write a hook for a medical school personal statement, you’ll want to think backwards. You can do this in multiple ways. First, think about the overall arc of your story. What point are you trying to convey about your experience and journey to medicine? Visualize the story in your mind and consider different points of entry to your personal statement for the reader. Write a few different opening sentences, then roughly outline what path each version of the essay would take by jotting down the main ideas for each subsequent paragraph. Personal anecdotes (true stories from your own life that demonstrate a concept or illustrate a point you want to make) can be a great point of entry. They make an essay feel unique and authentic without venturing into the overdramatic or cliche. Don’t worry about the sentences being expertly crafted at this point; you can refine them later. Then, change your perspective. Read your sentences from the reader’s point of view. Would the reader think your journey to medicine is as captivating as you do? What grabs you, if anything, about your potential hooks? Take notes about what you think and draw connections. Aim for something compelling that you can expand on later in your essay. Keep in mind that this is an iterative process. The idea is to draw your reader in to learn more about your interest in medicine, not to shock them and hope they see you as interesting enough to be admitted. Overly dramatic openers are like a sugar high for your personal statement—a quick boost of interest that quickly dissipates. We cover this in more detail with examples below in part four.

Paragraph 4

As soon as I walked into the examination room, I noticed the mother avoiding eye contact with the genetic counselor while clutching her son to her chest. I sensed her anxiety and disinterest in hearing about my research conclusions. The impact of her son’s condition on their daily lives probably transcended the scientific details in my report. So, despite my desire to get into the science, I restrained myself from overwhelming her. Instead, I asked her to share details about the wonderful interventions she had procured for her son—speech and physical therapy, sign language lessons, special feeds, etc. Through our conversations, I realized that she was really looking for reassurance—for doing a great job caring for her son. I validated her efforts and offered relief that there were other families navigating similar difficulties. As the appointment progressed, I observed her gradually relaxing. Rather than feel weighed down by the research findings I was eager to get off my chest, I felt light as well.

The applicant right away begins to describe their meeting with the boy and his mother. We understand that while the applicant was ready to share their research with the family, the mother appears anxious and is more interested in understanding how she can help her son.

It should also be noted that the applicant does not judge the mother in any way and offers supporting evidence for their conclusions about what the mother must’ve been thinking and feeling. For example, rather than just call the mother “anxious,” the applicant first describes how she avoided eye contact and clutched her son tightly.

The applicant once again demonstrates their flexibility by showing how they modified their talking points to fit the family’s needs rather than satisfy their own curiosity and self-interest. Moreover, they highlight not only the approach they took with this family, but also the impact on their care. For example, after discussing how they validated the mother’s care efforts, the applicant mentions how the mother relaxed.

Socially aware (e.g., “I noticed the mother avoiding eye contact with the genetic counselor while clutching her son to her chest. I sensed her anxiety and disinterest in hearing about my research conclusions. The impact of her son’s condition on their daily lives probably transcended the scientific details in my report.”)

Flexible (e.g., “So despite my desire to get into the science, I restrained myself from overwhelming her. Instead, I asked her to share details about the wonderful interventions she had procured for her son—speech and physical therapy, sign language lessons, special feeds, etc.”)

Socially skilled and validating (e.g., “Through our conversations, I realized that she was really looking for reassurance—for doing a great job caring for her son. I validated her efforts and offered relief that there were other families navigating similar difficulties.”)

At first glance, it may appear that this paragraph is as much about the mother as it is about the applicant. After all, the mother procured various services for her son and has done a marvelous job of caring for him.

Nevertheless, the applicant is not competing in any way with the mother. By demonstrating their flexibility and social skills, the applicant reinforces great qualities they’ve demonstrated elsewhere and remains at the top of our minds.

In isolation, perhaps. However, at this point in the personal statement, along with the loads of insights, thoughts, and feelings, there’s no question that this story is unique to the applicant.

This paragraph is another model of depth. The applicant goes into highly specific details about a memorable experience with a specific family. There’s significant showing vs. telling, which continues to maintain the reader’s engagement.

Paragraph 5

How many people should i ask to review my personal statement.

Typically, we recommend that no matter than two people—people who have experience evaluating med school personal statements—review your essay. Everyone you show your essay to will have an opinion and suggest changes, but trying to appease everyone usually leads to diluting your own voice. And even if your personal statement is great, someone will eventually identify something they perceive to be an issue, which will only exacerbate your anxiety. Two people is a good number because you can receive more than one opinion but avoid the problem of having too many cooks in the kitchen.

The final paragraph accomplishes three key goals:

Concluding the story about meeting the boy and his mother;

Bringing the applicant’s insights full circle; and

Restating their interest in medicine while offering a preview of what type of physician they intend to be.

By describing how they built a trusting relationship with the patient and his mother, the applicant deliberately continues the theme of patient-centered care ultimately being more important to them—and to medicine—than underlying pathologies and interestingness of various medical scenarios.

Although the applicant does not circle back to the classroom story in the introduction, they close the loop with the personal statement’s central and most important story. In addition, they end on a high note by mentioning how enthusiastic they are about their medical career.

Trustworthy (e.g., “At the end of the appointment, the mom offered to let me hold her son, who gazed back at me with his bright blue eyes.”)

Insightful (e.g., “Above all, this experience allowed me to recognize that interactions between a patient plus family and their doctor are more than intermediary vehicles to treatment; they are critical and beneficial in their own right.”)

Patient-centered and caring (e.g., “While research is essential and will surely always trigger my curiosity, I want my work to transcend the lab bench. Specifically, I want to continue engaging with patients and helping them through life’s difficult moments—with physical treatment and genuine support.”)

This paragraph is all about the applicant. Even the detail about cradling the boy highlights their earlier efforts in building trust with the family. After this brief conclusion to the story, the applicant explores their own developing insights about the field and how they intend to practice medicine in the future.

In combination with the insights shared in this paragraph, the story and details up to this point round out the personal statement uniquely.

Conclusion paragraphs should summarize insights and information presented earlier in the personal statement. The applicant does a fine job of solidifying their longstanding interest in medicine without adding significant new details, knowing they can cover additional stories throughout their secondary applications and during interviews .

Can you say a little more about how I can write my essay so that it's clear I want to go into medicine and not another health care field?

- A long-term commitment to medically-relevant experiences

- A clear understanding of what medicine entails that other fields don't

At various points while writing your personal statement, you may wonder whether your essay is “good enough.”

The goal of this guide isn’t to allow you to compare your personal statement to the sample we’ve provided. Rather, we want you to have a framework for evaluating your work to ensure that it conveys your outstanding qualities, engages the reader, and describes your authentic journey to medicine.

Did you find this example and analysis valuable? You can find 220+ exclusive personal statement examples at the following resource:

If you’re like most applicants, you’re worried about choosing a clichéd medical school personal statement topic . You fear that your application may be thrown into the rejection pile if you fail to present yourself in a unique way.

To help you avoid common pitfalls and write a memorable personal statement, we’ve highlighted eight different ways that unique personal statements differ from clichéd ones.

We’ll first describe the clichéd approach and describe why it’s problematic. Then we’ll provide specific writing techniques you can use to make your essay truly stand out.

Clichéd Approach 1: Only discussing experiences that you think make you seem the most impressive.

Most applicants begin writing their essays by choosing the experience(s) that they think will help them stand out to admissions committees. By focusing on specific experiences that applicants think will impress the admissions committee (e.g. clinical shadowing, research, and volunteering), students often forget to demonstrate their unique qualities.

Let’s see how this becomes a problem.

In your AMCAS Work and Activities section, you may have included your experience conducting chemistry research for three years, shadowing in a clinic for two years, volunteering as an English tutor for underserved youth in Chicago for six years, volunteering with a medical mission trip to Haiti for two summers, and serving as president of a premed organization for one year.

Given these choices, most students would choose to write about clinical volunteering in Chicago or their medical mission trip to Haiti because they think these experiences were most impressive. If you take one of these two approaches, you would probably start the essay by describing an interaction with a very ill patient or one with whom you experienced a language barrier.

An essay about clinical shadowing could start something like this:

Clichéd introduction

I used to eat lunch with Felipa on Wednesdays. She was always very nervous when she came in to get her blood drawn, and she liked to speak with me beforehand. Although she was suffering from breast cancer, she had a positive attitude that made the doctors and the nurses feel like one big family. Her positive attitude helped lift the spirits of other patients in the room. Throughout my lunches with Felipa, she would tell me how she still cooked dinner every day for her husband and two young kids. She brought that same compassion to the hospital, always with a contagious smile. I endeavored to give her the best care by offering her water and chatting with her on her chemo days. However, I was always bothered that I could not treat Felipa’s cancer myself. This powerlessness I felt inspired me to pursue medicine to help future patients battle this horrible illness by discovering new treatments.

While we gain some information about the applicant’s motivations to study medicine (e.g., to help future patients…by discovering new treatments ), it explores a common topic (i.e., a realization that came during clinical shadowing) with a typical delivery (i.e., written broadly about interactions with a specific patient).

The paragraph does not do a good job of painting a picture of the applicant, as we don’t learn about her standout qualities or other aspects of her identity.

Moreover, if we replace “Felipa” with another name, it becomes clear that any applicant who engaged in a similar shadowing experience could have written this paragraph. This is not to say that an essay that includes shadowing will always be clichéd. After all, the topic is only one aspect of your personal statement.

Remember, there are no good or bad topics. Rather, there are strong ways—and poor ways—to write about these topics.

Instead of asking if your topic is “good” or “bad,” you should be asking yourself whether your essay has a “typical” or “standout” delivery.

You want your personal statement to be written so engagingly that it serves as a pleasant interruption to the admissions committee member’s routine. Surprise them when they rarely expect to be surprised.

Unique Alternative 1: Demonstrating the qualities that make you distinct by choosing experiences that highlight your best characteristics.

The best personal statement writers decide which qualities they want to emphasize to admissions committees before choosing a certain experience. Then, they focus on a specific event or situation that captures the admissions committees’ attention by telling a detailed story—oftentimes a story that does not overtly involve medicine.

By deciding on your qualities beforehand, you will choose a story that authentically delivers your intended message.

Don’t be afraid to select an experience or story that strays from the typical, “impressive” premed extracurricular activity. After all, med schools want to accept applicants because of their wonderful qualities and unique attributes, not because of a specific experience or extracurricular activity.

Let’s imagine that the same applicant from the previous example chose to write about her community involvement outside of medicine.

From her list of extracurricular activities, she could choose to write about volunteering as an English tutor or being the lead saxophone player in a campus jazz ensemble. By picking one of these options, this student could write an entirely unique personal statement introduction.

Let’s see how an effective essay might begin with her volunteer work as an English tutor:

Unique introduction

I could feel the sweat rolling down my back as twenty first graders stared at me. It was July in Chicago, and the building where I volunteered as an English teacher twice a week did not have air conditioning. I had volunteered as a one-on-one tutor for the past six years, but this was my first time teaching a large group. The students, largely from working-class, Spanish-speaking households, reminded me of myself, as I grew up as the daughter of two Mexican emigrants. I personally understood the challenges the students faced, and I wanted to use my own experience and knowledge to help set them on the path to academic success.

This introduction would likely stand out to an admissions committee member not only because it discusses something other than clinical shadowing but also because it demonstrates the writer’s commitment to her community, and it reveals something about the applicant’s personal background.

Should I mention bad grades in my personal statement?

In most cases, no. With limited characters, your primary goal for your personal statement should be to tell medical school admissions committees why you will be an excellent doctor. Admissions committees will already see your grades. If you use too much space discussing your poor grades during freshman year or some other time, you'll draw even more attention to the red flags on your application and lose a golden opportunity to demonstrate your impressive qualities. One exception is if you received poor grades due to some extraordinary circumstance, such as recovering from a significant accident or illness. Even then, you might want to discuss your poor grades in another section of your application, such as a secondary essay.

Clichéd Approach 2: Listing your qualities and accomplishments like you are explaining your resume.

When many students begin writing their personal statements, they “tell” and don’t “show”.

Even though the advice to “show, don’t tell” is commonly given, students rarely know what it actually means to demonstrate or “show” their qualities rather than simply listing them.

We’ll provide an overly simple example to highlight why “telling” your qualities is such a problem:

Ever since I was a kid, I have received excellent grades and have excelled at all things related to science. My success in conducting chemistry research and my numerous presentations at biochemistry conferences is testament to my ability to succeed as a doctor. In fact, my family and friends have encouraged me to pursue this route because of my academic success.

While we learn that the applicant thinks that he is a great student who is excellent at science, and we learn that his family believes that he should pursue medicine because of his academic success, we do not actually see any evidence of these qualities. Sure, he tells us that his family thinks that he is brilliant, but we do not know why they think he is brilliant.

Unique Alternative 2: Showing, and not telling, the applicant’s qualities.

When you demonstrate your best qualities through examples, you provide a more authentic glimpse about the type of person you really are.

For instance, if you read the following sentences from two different applicants, who would you think was more caring?

Applicant 1: I am very empathic.

Applicant 2: Volunteering with elderly Japanese women has taught me how aging immigrants face cultural barriers while also navigating health problems, from diabetes to cancer.

Even though Applicant 1 says that they are empathic, you probably picked Applicant 2, even though she never uses the word “empathic” (or a synonym) in her sentence. As the reader, you were able to extrapolate how empathic that applicant is by seeing what they do.

Returning to the introductory paragraph with Felipa from example 1, we can see that the typical introduction “tells” about the applicant’s qualities, whereas the standout paragraph “shows” the applicant’s qualities. Let’s look at some examples to clarify:

I endeavored to give her the best care… (giving)

This powerlessness I felt inspired me to pursue medicine to help future patients… (inspired)

I had volunteered as one-on-one tutor for the past six years, but this was my first time teaching a large group. (dedicated, risk-taking)

I personally understood the challenges the students faced, and I wanted to use my own experience and knowledge to help set them on the path to academic success (giving, empowering, empathetic)

Is it OK to discuss a mental health condition in my med school personal statement?

You might have heard that, given the stigma surrounding many mental health conditions, that you should avoid discussing them in your personal statement, no matter what. However, as with many things related to med school essays, the answer depends on the specific condition, severity, and reason behind sharing it. Certain conditions have more stigma associated with them than others and are therefore more difficult to sensitively incorporate in your personal statement. But regardless of your specific mental health condition or its severity, it’s important to ask yourself why you would share it. For instance, if the primary reason for sharing your mental health condition is to show adcoms how much adversity you have overcome, then you should probably leave out your condition or reconsider why you would share it. However, if your reason is to describe the insights you developed about people and about medicine, or how your condition served as a springboard for you to pursue certain activities, then it might be worthwhile to share. Writing about mental health conditions in your personal statement should be approached delicately, so make sure to work with someone who has experience doing so.

Clichéd Approach 3: Stating that you want to be a physician to help people or talking about how being a doctor is such an honor.

When you ask medical school applicants why they want to be a doctor, they usually say that they want to help people. While you should include this fact in your personal statement, it can be difficult to articulate why you want to help people or how you will help them in a way that is not clichéd.

Most applicants will probably write some version of the following in their personal statement:

I want to be a physician because I want to help people who are sick. It would be an honor to serve people in need.

The problem with these statements is that any applicant could have written them. Every doctor wants to help patients who are sick or in need.

Failing to offer a specific reason for your motivation to become a doctor or a specific way in which you plan to help your patients will make it hard for the admissions committee to see what unique approaches and insights you will bring to medicine.

Unique Alternative 3: Explaining specific ways that you intend to help patients or specific reasons why you want to help patients.

To make your statement more convincing, you could add a specific method that you will use to help patients. Consider the following example:

I want to become a physician to provide reassurance to a patient awaiting their lab results, and laughter to a patient who needs an uplift after a week of chemotherapy.

Whereas any medical school applicant could have written the statement in the clichéd example, the statement in the unique example demonstrates specific qualities about the applicant. By explaining that certain patients might need reassurance while others might want laughter, the applicant shows us that they are empathic and sensitive to the needs of individual patients.

To make your statement more authentic, you can also explain why you are drawn to a specific aspect of medicine or a certain demographic of patients. Let’s look at another example:

As a woman with PCOS, I want to improve the field of women’s health so that I can provide other young women comfort and reassurance as they come to terms with their bodies.

This applicant shows that she is passionate about women’s health by connecting her desire to enter medicine to her own health condition. This statement suggests that she will use her own experience to empathize with patients when she becomes a physician.

Should I mention my desired specialty in my med school personal statement?

Probably not. Admissions committees want to recruit students who are incredibly curious and open to different training opportunities. Highlighting a desire to enter a specific specialty might make you seem closed off. That said, it's perfectly fine to express a commitment to serving certain communities or a desire to address specific issues so long as you don't inadvertently box yourself in.

Clichéd Approach 4: Focusing too much on characters who are not you.

The previous two approaches focus on how your personal statement introduction should tell a story. And what do we need for a great story? A character!

Applicants often make another character (e.g. a family member, patient, a physician they shadowed or worked under) the most compelling and interesting character. But when you give or share the limelight with another character, you make it easy for the admissions committee to forget the most important person in the story: YOU. You should be the star of your own personal statement.

We are not saying that you should avoid including another character in your personal statement. In fact, including other characters in your statement reminds the admission committee that you have had a positive impact on other people.

However, these other characters must be used to demonstrate your qualities. These qualities can come from an insight you had while interacting or observing them.

We see how this becomes a problem in the clichéd paragraph from example 1. Felipa and the applicant are both main characters. Indeed, we don’t even read about the applicant or their insights until the seventh sentence. Who knows? Admissions committees might even offer Felipa an interview instead of you.

Unique Alternative 4: Maintaining the focus on the main character—you!

In contrast, the unique paragraph from example 1 about the English tutor in Chicago tells us about the applicant’s passions, commitments, and initiative. Let’s revisit the example:

I personally understood the challenges the students faced, and I wanted to use my own experience and knowledge to help set them on the path to academic success.

Even though she writes about tutoring first-grade students in Chicago, their role in the story is to highlight how she is dedicated to helping her community and empowering students from backgrounds like hers. The students never get in the way of us learning about the applicant.

Now, you may be worried that focusing on you and your qualities will make you come off as arrogant or cocky to the admissions committee. By letting the stories do the talking for you, your personal statement will avoid making you appear egoistical. On the other hand, saying that you are a “good person” or “brilliant” without telling a story can make you seem arrogant.

With only 5,300 characters, you should aim to keep the emphasis almost entirely on you.

Looking for unique personal statement examples to accelerate your writing? We’ve got more than two hundred of them.

Clichéd Approach 5: Focusing too much on describing the activity itself.

Many applicants will write about clinical shadowing, volunteering, or research at some point in their personal statements. Sometimes, however, applicants are so excited by the activity that they forget to include themselves in the experience.

For instance, an applicant looking to highlight their work in a prestigious lab might write:

Working in Dr. Carpenter’s lab, an endowed professor at Harvard Medical School, was exhilarating. The main research project was an experiment that explored how rats responded to various stimulant medications. Our results demonstrated that one of the drugs we tested on the rats may have significant promise for treating Alzheimer’s disease.

While this paragraph demonstrates the student’s familiarity with and excitement about original research, it does not tell us much about the applicant’s specific characteristics or contributions. We learn about the research project in Dr. Carpenter’s lab, but we don’t know what qualities or insights the applicant has gained from conducting the research.

Unique Alternative 5: Unique statements explain how you made an impact through an activity and how the activity impacted you.

While you may think that highlighting a research experience with a famous doctor or in a prestigious lab will bolster your application, writing about it in your personal statement may actually harm you if you do not highlight your own accomplishments and traits.

Focus on activities where you had an impact, even if the activity itself does not seem impressive. Consider the following examples:

Applicant 1: While working in Dr. Smith’s lab, I managed five interns. To make the lab a more congenial environment, I started a weekly lunch hour where we could all discuss our different research projects. This opportunity gave the interns more confidence to talk about their individual lab work, which made it easier for the entire research staff to collaborate on different experiments.

Applicant 2: Working in Dr. Martin’s lab with five other interns taught me the importance of serving on a team. When one of our experiments failed, I made sure that the group met to discuss the results. I offered advice to my lab mates on how they could obtain better results on the next trial. This experience taught me the importance of learning new research methods from my peers to achieve the best results possible.