- DSpace@MIT Home

- MIT Libraries

- Graduate Theses

Methodology in architectural design

Terms of use

Description, date issued, collections.

Show Statistical Information

Methodological research in architecture and allied disciplines: Philosophical positions, frames of reference, and spheres of inquiry

Archnet-IJAR

ISSN : 2631-6862

Article publication date: 15 March 2019

Issue publication date: 15 March 2019

The purpose of this paper is to contribute an inclusive insight into methodological research in architecture and allied disciplines and unravel aspects that include philosophical positions, frames of reference and spheres of inquiry.

Design/methodology/approach

Following ontological and epistemological interpretations, the adopted methodology involves conceptual and critical analysis which is based on reviewing and categorising classical literature and more than hundred contributions in architectural and design research developed over the past five decades which were classified under the perspectives of inquiry and frames of reference.

Postulated through three philosophical positions – positivism, anti-positivism and emancipationist – six frames of reference were identified: systematic, computational, managerial, psychological, person–environment type-A and person–environment type-B. Technically oriented research and conceptually driven research were categorised as the perspectives of inquiry and were scrutinised together with their developmental aspects. By mapping the philosophical positions to the frames of reference, various characteristics and spheres of inquiry within each frame of reference were revealed.

Research limitations/implications

Further detailed examples can be developed to offer discerning elucidations relevant to each frame of reference.

Practical implications

The study is viewed as an enabling mechanism for researchers to identify the unique particularities of their research and the way in which it is pursued.

Originality/value

The study is a response to a glaring dearth of cognisance and a reaction to a growing but confusing body of knowledge that does not offer a clear picture of what research in architecture is. By identifying key characteristics, philosophical positions and frames of reference that pertain to the research in architecture and associated disciplines, the findings represent a scholastic endeavour in its field.

- Architecture

- Built environment

- Research methods

Salama, A.M. (2019), "Methodological research in architecture and allied disciplines: Philosophical positions, frames of reference, and spheres of inquiry", Archnet-IJAR , Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 8-24. https://doi.org/10.1108/ARCH-01-2019-0012

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2019, Emerald Publishing Limited

1. Introduction

In today’s rapidly transforming academia, knowledge construction, production and reproduction are increasingly valued and are now regarded as salient qualities of research processes that examine environmental and societal challenges facing the built environment and that seek opportunities those challenges create. Thousands in architecture and allied disciplines worldwide are involved in research activities on a routine basis. They have chosen their careers to construct and cultivate diverse forms of knowledge on contemporary thematic issues of interest to the academic and professional communities. Nonetheless, except for a few undertakings ( Franz, 1994 ; Groat and Wang, 2002 ; Preiser et al. , 2014 ; Lucas, 2016 ), there has been a glaring dearth of cognisance of the key characteristics, philosophical positions and frames of reference that pertain to methodological research in architecture and associated disciplines together with a scarcity of the scholastic endeavours involved in remedying this. Consequently, recent concerns about the recognition of what constitutes methodological research in architecture within higher education present new opportunities for academics and professionals to strengthen their understanding of research, its relationship with pedagogy and professional practice, and its overall role in advancing knowledge that genuinely benefits architecture and built environment professions.

There have been, and still are, continuous debates within architecture and allied disciplines about the role, nature, attributes of research. Discussions among academics and professionals suggest that architects and other design and built environment professionals seem to be at odds. While many still think of researchers as individuals in white smocks and thick glasses searching for the inscrutable and the mysterious, others present clouding arguments about the role and essence of research. This is associated with a growing but confusing body of knowledge that explicitly raises the question of “what is architectural research” or “what is architectural design research” but does not offer much other than blurry answers. Bryan Lawson (2015) made a very perceptive argument about one of the recent contributions in the field: “ Design Research in Architecture: An Overview, ” edited by Murray Fraser (2013) : “This is certainly an interesting and stimulating read and it offers a fascinating glimpse of the personal development of many of its authors. It represents a strong set of beliefs that design and research can be intertwined but it remains confused and muddled about the central questions. It is a shame the authors feel the need to focus exclusively on architecture. At times one gets the feeling that this book is really about architecture and ways of seeing and promoting it rather than about either design or research. Unfortunately the total result is a confusing mishmash that is insufficiently disciplined and rigorous to further progress research in design” ( Lawson, 2015 , p. 129). This, in essence, reflects the reality of the current state of affairs with respect to many of the writings on architectural or design research.

This paper attempts to decipher methodological research in architecture and allied disciplines on a more strategic and conceptual basis. Building on the earlier contributions of Franz (1994) , Groat and Wang (2002) , and the author’s own research and writings on the role of research in architectural and design pedagogy ( Salama, 1998, 2008, 2012, 2015 ), the paper constructs a conceptual understanding of research. Ontological and epistemological interpretations are utilised for examining three key philosophical positions: positivism, anti-positivism and emancipationist. Reviewing classical writings and more than hundred contributions in architectural and design research, six frames of reference were identified: systematic, computational, managerial, psychological, person–environment type-A and person–environment type-B. Accentuated by these frames of reference, technically oriented research (TOR) and conceptually driven research (CDR) were categorised as perspectives of inquiry, which were scrutinised and their developmental aspects were explored. By mapping the philosophical positions to the frames of reference, various characteristics and spheres of inquiry within each frame of reference were revealed. Additional spheres of inquiry were inferred as branching various frames of reference, but mainly from the person–environment frame of reference: traditional dwellings and settlements research, quality of urban life research, and educational and pedagogical research. The study concludes with a number of qualities that depict an overall understanding of methodological research in architecture and allied disciplines.

2. Philosophical positions/systems of inquiry

While discussing the very few efforts on methodological research in architecture and allied disciplines goes beyond the scope of this analysis, it is important to refer to the classical work of Groat and Wang (2002) , which calls for the need to understand research methodologies hierarchically with respect to systems of inquiry/paradigms, strategies and tactics. This is a very insightful proposition and can be regarded as a response to the inherited tendency of researchers in architecture and allied disciplines to blur or confuse methodologies and systems of inquiry at a strategic level with methods, tactics and tools at an operational level. Groat and Wang propose a ‘cluster of systems of inquiry’ or paradigms as an integrative framework for research, drawing on contributions from methodological studies in architecture and the social sciences. In this context, the systems of inquiry can be articulated based on three philosophical positions.

Following ontological and epistemological interpretations, two important philosophical positions can be examined to better understand the diverse nature of research in architecture and allied fields: positivism and anti-positivism. Ontology is the branch of metaphysics that deals with the nature of reality, while epistemology is the branch of philosophy that examines the nature of knowledge ( OED, 2012 ), its foundation, extent and validity; it examines the way in which knowledge about a phenomenon can be acquired, conveyed and reproduced. Positivism and anti-positivism can be interpreted ontologically and epistemologically as they relate to the built environment ( Salama, 2015 ). For architecture and allied disciplines, how these two positions are translated into a practical understanding of built environment research remains a conceptual challenge.

Positivism, as it relates to ontology, adopts the premise that objects of sense perception exist independent of the researcher’s mind: this means that reality is understood to be objective. Epistemologically, positivism views knowledge as being independent of the observer, as objectively verifiable. Positivists believe that the best way to learn about a phenomenon is by the discovery of universal laws and principles. Thus, in positivist thought, the built environment is examined by the researcher as an objective reality with components and parts that everyone can observe, perceive and agree upon. Consequently, adopting positivism is exclusionary as it leads to the suppression of multiple viewpoints, thoughts and voices.

In a stark contrast, anti-positivism, as it relates to ontology, predicates the notion that universal laws and principles do not exist outside of the researcher’s mind. In other words, people as individuals and as groups perceive reality differently and that these perceptions are both equal and legitimate. Epistemologically, anti-positivism adopts the understanding that although individuals and groups acquire different types of knowledge about the same phenomenon, the variances are regarded as valid and important mechanisms for mutual acknowledgement ( Salama, 2015 ).

Drawing from critical writings in the social sciences ( Denzin and Lincoln, 2000 ; Lincoln et al. , 2011 ), Groat and Wang (2002) introduce a third position; emancipationist as the most recent position, which, similar to the anti-positivist, covers several emerging research methodologies. Ontologically, emancipationists adopt the view that there are multiple realities that are shaped by the full spectrum of contextual values including social, political, cultural, economic, ethnic, gender and disability aspects. Epistemologically, knowledge is historically and contextually situated where researchers are active participants, not only discovering and analysing realities, but also engaging with and intervening in these realities. The understanding of the preceding three philosophical positions within ontological and epistemological interpretations should be an imperative for starting any research activity ( Figure 1 ).

3. Perspectives and frames of reference

Methodological research in architecture and design has been examined in an article published in the mid-1990s by Jill Franz ( Franz, 1994 ). Although the context and content of Franz’s categorisation have evolved significantly since it had been developed 25 years ago, certain aspects of the classification skeleton seem to be still valid and soundly inclusive. Underscored by explicit frames of reference, TOR and CDR are two perspectives of inquiry in architecture and allied disciplines and are pertinent to the scope of this analysis.

3.1 Technically oriented research (TOR)

Three “frames of reference” appear to characterise the TOR. These are: the systematic, the computational and the managerial. In essence, TOR places emphasis on the process and procedures as the primary basis of effective design ( Franz, 1994 ). Within the systematic frame of reference, the supremacy of consumerism and industrialisation during the 1950s resulted in perceiving design knowledge as essential for improving production, developing processes to suit intended qualities in the end product, and implementing designs to accommodate users’ needs. Architecture and allied design and built environment disciplines considered “performance” as a goal, leading to a sustained quest by design researchers to make the design process more efficient and effective ( Hensel, 2010 ). Consequently, during the following decades and up to the late 1980s, a “rational” approach to knowledge acquisition, assimilation and accommodation in a systematic design process has dominated design discourse. The works of Alexander (1964) , Markus (1972) , Broadbent (1973) , Sanoff (1977) and Cross (1984) represent principal thinking and examples of the systematic application of technique which instigated a design research culture that advocated a more explicit and transparent design process though underpinned by a linear conception of designing.

While they have evolved relatively in parallel, the systematic frame of reference seems to have paved the road for the computational frame of reference. Researchers viewed designing as a process amenable to depiction into decomposable components, represented numerically, and interpreted and administered by a computing machine and software. The computational frame of reference stemmed from research and theoretical foundations which include cognitive science, expert systems and artificial intelligence ( Whitehead and Eldars, 1965 ; Eastman, 1969 ; Maver, 1971 ; Newell and Simon, 1972 ; Mitchell, 1979 ). The works of Mitchell (1979, 1990) , Gero (1983) and Gero and Maher (1993) demonstrate well-recognised achievements on the utilisation of systems thinking and machine learning in design that drifted into two directions. The first is computer aided design (CAD), which aimed at improving the efficiency of processes and products, and the second is knowledge-based design which entailed the understanding of design as a heuristic research process that fostered designers’ knowledge of the relationship between potential solutions and performance requirements. These efforts led to the recently developed building information modelling/management (BIM) approach to design ( Sacks et al. , 2018 ), which is now used as part of research on the application of the information and communication technologies in design and construction and is adopted as a necessary tool for practice within built environment professions ( Kumar, 2015, 2018 ).

Notably, the systematic and computational frames of reference have gained significant interest within the design research community for several decades as evident in the surge of published research. However, in comparison, the managerial frame of reference does not seem to have attracted the same level of attention given the available body of knowledge in this area. In it, research is centred on the examination of the nature of architectural services, design teams, office management within an architectural practice and project delivery processes. It also involves investigating various aspects of the profession, its position within other design and built environment professions, and the way in which it is perceived by society. The works of Burgess (1983) , Akin (1987) , Gutman (1975, 1988) , Cuff (1991) and Sanoff (1992 ), and more recently of Fisher (2006, 2010) , Awan et al. (2011) , Till (2013) and Brown et al. (2016) , represent important examples that scrutinise ways in which contemporary practices can be more responsive to the demands placed on the profession by the society. Likewise, recent research raises questions about the role and types of research utilised within professional practice ( Dye, 2014 and Samuel and Dye, 2015 ).

3.2 Conceptually driven research (CDR)

Vital to the CDR perspective, two primary frames of reference are explored. The first is a psychological frame of reference, and the second is a person–environment frame of reference. Embracing the psychological frame of reference, design researchers incline to espouse the belief that designing is a process that involves three key qualities. As a “rational” process, it encompasses information processing across various developmental phases, as a “constructive” process it builds on knowledge generated from past experiences, and as a “creative” process it utilises conjectural reasoning ( Lawson, 1980 ; Heath, 1984 ; Rowe, 1987 ). In this respect, research is driven by the goal of matching knowledge with the nature of the design problem, its components, context and social and environmental requirements. According to Franz (1994) , research focussing on the nature of design problems ( Rittel and Webber, 1973 ), problem definition and solution generation ( Simon, 1973 ; Wade, 1977 ), and design knowledge ( Thomas and Carroll, 1979 ; Goldschmidt, 1989 ) reflects endeavours that accept the linear approach of problem solving ( Akin, 1986 ), which perceives people and objects as isolated entities within the design/research process. However, the recent of work of Goldschmidt (2014) introduces linkography as a new method for the notation and analysis of the creative process in design, which adopts a “good-fit” approach, drawing on insights from design practice and cognitive psychology.

Within person–environment frame of reference, design researchers place emphasis on the socio-cultural and socio-behavioural factors as they relate to the design process itself and to settings, buildings and urban environments. The increasing awareness of social reality and the growth of community-driven programmes during the 1970s generated interest in collaborative and democratic design processes. Sanoff’s (1978, 1984) simulation games, Lawrence’s (1987) environmental models and Hamdi’s (1990) enabling mechanisms are pioneering examples of how social, cultural, and behavioural issues are investigated within the design process. Aligning with the notion of collaboration in design, researchers focussed on the development of arguments, models, methods and tools ( Hester, 1990 ) that could support client/user engagement in the design process. While Sanoff (2000, 2010) continues to pursue his quest for collaborative design research practices following his previously established approach, other scholars, in other contexts, attempt to unfold social and political aspects of the built environment and the way that the future users may shape it ( Blundell-Jones et al. , 2005 ) interrogating issues that pertain to how architects can best enhance their partnership with users and the wider society to deliver responsive environments ( Jenkins and Forsyth, 2009 ). In essence, underpinned by the belief that reality for an individual is socially and politically constructed and is primarily determined by social and cultural norms – what is unique in the collaborative approach is the sharing of values and acting collectively on knowledge about how requirements can be achieved and how needs can be met.

Another primary form of research within the person–environment frame of reference places emphasis on the meaning of place and the nature of the user in relation to physical, social and cultural environments. It acknowledges the crucial need for broader inter-disciplinary and trans-disciplinary approaches to inquiry. The work of environment–behaviour studies/research community (EBS/EBR) represents this form of research that has expanded significantly as part of two important organisations: Environmental Design Research Association (EDRA) which operates mainly within the North American context, and the International Association for People-Environment Studies (IAPS) which operates in Europe. Established in 1969 and 1981 respectively, both organisations continue to generate interdisciplinary research that places emphasis on the investigation of user requirements and is conducted by sociologists, environmental psychologists, social psychologists and design professionals ( Shin et al. , 2017 ; IAPS, 2018 ).

Integral to the person–environment frame of reference research aims at understanding the complexity of human behaviour within the built environment from an experiential standpoint. Examples include examining the psychological factors of place ( Canter, 1974, 1977 ), the reciprocal relationship between culture and environment ( Altman and Chemers, 1980 ), place identity and how it is influenced by feelings and behaviours within certain physical settings ( Proshansky, 1990 ), and the meaning and influence of culture on the built form ( Rapoport, 1969, 1977, 1990 ); an area of research that has gain continuous interest ( Rapoport, 2005, 2008 ). Other areas of research involve examination of social life in urban space ( Whyte, 1980 ), environmental perception, experiential aesthetics, visual research methods ( Nasar 1988 and Sanoff, 1991 ) and wayfinding in complex environments ( Passini, 1992 ; Cooper, 2010 ), to name a few.

The associated practical repercussions of the person–environment research were materialised in two areas of design research that focus exclusively on users and are viewed as fundamental to the design process, while offering the opportunity for a better-informed decision making on future built environments; programming ( Preiser, 1985 ; Hershberger, 1999 ) and post-occupancy evaluation (POE) ( Marcus, 1972; 1985 ; Preiser et al. , 1988 ). Research within the person–environment frame of reference applies various tools which stem from social and psychological sciences including archival documentation, attitude surveys, focused and semi-focused interviews, participant and nonparticipant systematic observation, and cognitive and behavioural-mapping techniques.

4. Emerging spheres of inquiry within TOR and CDR

The preceding conceptual analysis enables a comprehensive, yet inclusive, understanding of methodological research in architecture and allied disciplines. While the analysis discerns TOR and CDR as two distinct perspectives together with their frames of reference ( Figure 2 ), assessing the developments within these perspectives is a separate research exercise on its own. Nevertheless, looking at the recent landscape of academic and professional research certain spheres of inquiry can be perceived as developments of the TOR and CDR.

4.1 Developments in technically oriented research (TOR)

The systematic frame of reference does not seem to have developed as a distinct research area beyond the 1990s. The recent body of knowledge, however, suggests that the computational frame of reference has advanced dramatically into a clear sphere of inquiry that demonstrates the renewed interest in virtual reality to visualise, understand, and articulate data to enhance planning, design and construction decisions ( Whyte and Nikolic, 2018 ). This involves a spectrum of sub-areas ranging from CAD/BIM modelling to virtual and augmented reality and from immersive visualisation to the development of virtual platforms for heritage preservation ( Goulding and Rahimian, 2015 ; Abdelmonem, 2017 ).

The systematic and computational frames of reference appear to have merged into two growing areas of research. The first pertains to environmental sustainability in buildings and environments, as evident in the annual conferences of Passive and Low Energy Architecture organisation and Architectural Science Association. Both are evidently focussing on making the discipline more scientific. This sphere of inquiry includes empirical, experimental and simulation-based investigations, utilising advances in information technologies in developing new insights into passive and climate design, thermal comfort, energy efficiency, low carbon design, daylighting and indoor environmental quality within design processes and for the development of new knowledge within academic research ( Zuo et al. , 2016 ; Roaf et al. , 2017 ; de Dear et al. , 2018 ). The second is concerned with Space Syntax approach to forecasting planning and design implications. It incorporates mathematical and configurational techniques utilising computers for the analysis of spatial configurations while enabling architects and urban designers and planners to simulate socio-physical impacts of their designs and plans with a focus on spatial integration, centrality, connectivity and accessibility ( Hillier and Hanson, 1984 ; Hillier, 2015 ).

The critical nature of research and writing within the managerial frame of reference appears to continue to lessen interest in this area where scholars seem to avoid assessing and criticising the profession and its organisations. This is despite the significant influence of its advocates in attempting to revolutionise the profession and to develop new modes of architectural practice in various ways but with a clear focus on social and political contexts within which the profession operates. The managerial frame of reference, however, has expanded beyond the profession of architecture to clearly advance new spheres of inquiry in integrated design and construction practices, design management, facility management, project lifecycle management and sustainable construction ( Anumba, 2005 ; Emmitt et al. , 2009 ). Yet, within conventional academic and professional circles in architecture and design fields, these areas are valued as completely different spheres of inquiry that are related more to engineering but not germane to architecture and urbanism.

4.2 Developments in conceptually driven research (CDR)

Similar to the systematic frame of reference, the psychological frame of reference has not progressed into a contemporary research trend given the scarcity of writings in this field. Yet, recent contributions suggest that while not a mainstream sphere, it remains essential given the quality of the leading journal in this area: Design Studies , and the birth of the new journal, Design Science , though not exclusive to architecture and built environment studies. As a sphere of inquiry it maintains interest in cognition, visual and creative thinking in design, and the way in which designers reason and generate concepts and ideas ( Casakin and Kreitler, 2011 ; Goldschmidt, 2014 ; Cross, 2016 ; Oxman, 2017 ; Darbellay et al. , 2018 ).

The person–environment frame of reference, focussing on collaboration and engagement with users and communities as part of an action design/research process seems to have developed into a distinct sphere of inquiry directly linked to professional practice. This is evident in the recent writings of its pioneers, coupled with interests of governments and local authorities in engaging with communities in regenerating old city centres or shaping new residential communities. It is also manifested in the rising interest of a considerable number of architectural firms to work closely with client groups, as well as in the annual conferences of the Association for Community Design; an organisation committed to increasing the capacity of planning and design professions to better serve communities. The surge of interests in action and collaborative research is palpable in recent writings that articulate cases of and offer guidance on how architects, urban designers and planners can genuinely engage with communities ( Malone, 2018 ; Norton and Hughes, 2018 ).

With a focus on users and communities in relation to the physical, social and cultural worlds, the person–environment frame of reference maintains its solid foundation on the initial set of themes in the psychology of place, place identity and attachment and the reciprocal relationship between cultural and behavioural factors and built form as evident in the research work of the EBS/EBR community. New themes have emerged over the past two decades to include resilience, social equity, healing environments, therapeutic landscapes and dynamic interactions of environment–behaviour and neuroscience. Older and new themes were applied to various environments ranging from small settings and interior spaces to different types of learning of environments, workplaces and nursing homes, and from small urban spaces to neighbourhoods and cities. The accompanying practical ramifications of the person–environment frame of reference have also developed into new areas. In particular, evidence-based design ( Hamilton and Watkins, 2009 ), and POE which has developed into a recognised sphere of inquiry, namely, building performance evaluation that extended beyond the exclusive focus on the user to address other relevant aspects including assessing energy use, usability, productivity, and functional, environmental, perceptual and social impacts ( Bordass 2001 ; Bordass and Leaman, 2014 ; Duffy, 2014 ; Mallory-Hill et al. , 2012 ; Preiser and Nasar, 2008 ; Preiser and Vischer, 2012 ).

It can be argued that the person–environment frame-of-reference has supported the growth of social and cultural sustainability sphere of inquiry. On the one hand, cultural sustainability involves efforts to preserve the tangible and intangible cultural elements of society ( Wessels, 2013 ). On the other hand, social sustainability involves various elements already adopted by EBS/EBR academics and professionals including democracy and governance, equity, socio-economic diversity, social cohesion and quality of urban life ( James, 2015 ), which is treated as a growing sphere of inquiry on its own.

4.3 Mapping the frames of reference to the philosophical positions

The philosophical positions discussed earlier manifest ideological orientations of research while the frames of reference discern the guiding principles and spheres of inquiry. In this respect, it is important to conceptually relate these ideological orientations to the frames of reference, in order to characterise the attributes of research areas into features or types guided by the frames of reference and within overarching ontological and epistemological interpretations ( Figure 3 ). Despite the clear distinctive qualities of these orientations, it should be noted that philosophical positions may alternate within a sphere of inquiry or a specific research activity depending on the research focus, the nature and context of the inquiry process, the type of environment and population under examination, as well as access to the information.

5. Expanding into growing spheres of inquiry

Arguably, research adopting the person–environment frame-of-reference has diverged into a number of spheres of inquiry that can be epitomised in three categories. The first two are traditional dwellings and settlements research and quality of urban life research. Although these areas involve various social, political, environmental, economic and historical dimensions people as individuals, groups and communities remain at the core of research within these areas. The third is educational and pedagogical research in architecture and built environment, which is unconventional in the sense of its acceptability as a growing sphere of inquiry. Due to the diversity of interests and themes within this category pedagogical research seems to be generated by various frames of reference, with a focus on learning, knowledge acquisition, assimilation, production and reproduction.

5.1 Traditional dwellings and settlements research

Over the past few decades, interest in traditional settlements research has become common among researchers within various disciplines including architecture, anthropology, art history, geography, urban history and planning. This is evident in the biennial international cross-disciplinary conferences of the International Association for the Study of Traditional Environments, which was established in 1988 to act as an interdisciplinary platform for knowledge sharing on cross-cultural and inter-disciplinary understandings of these environments. This is coupled with the semi-annual, highly valued journal: Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review , which publishes quality research findings. The organisation and its pioneers adopt the view that tradition is a dynamic concept for the reinterpretation of the past in light of the present ( AlSayyad, 2014 ). Utilising various tools from the humanities and social sciences, among the areas explored are the ways in which built forms embodies cultural norms, informality, socio-spatial practices especially of minority groups, everyday urban environments, authenticity and the notions of imagined and manufactured heritages and traditions.

5.2 Quality of urban life (QoUL) research

While studies on the quality of life (QOL) have emerged in the 1960s and flourished in the 1970s involving the development of economic and social indicators (Pacione, 2003), the spatial dimension was introduced later. The urban element was added as a significant physical dimension within which the social and economic imperatives take place (UoUL). As a sphere of inquiry, it is concerned with the relationship between a person’s QOL and their urban environment, which is complex and warrants measuring. This has encouraged researchers to develop QoUL models that articulate a wide spectrum of indicators that influence such a relationship; the development of models has become a subject of studies on its own ( Marans and Stimson, 2011 ; Marans 2012 ). Research is undertaken at the urban and city scales and involves implementing a range of measurement tools that include trend analysis through census and archival records, satisfaction surveys, interviews and techniques derived from EBS/EBR. As an area of research it is embraced by governments and appears to occupy a key position within contemporary urban discourse.

5.3 Educational and pedagogical research

For many decades questioning the realities of architectural education and design studio pedagogy has been a taboo, un-debatable and incontrovertible. The roots of this sphere of inquiry started in the 1950s but with many writings epitomising fragmented and disconnected issues that were often dealt with either by subjective criticism or by undeveloped and even untried solutions. However, as a sphere of inquiry it has developed distinctively since the early 1990s ( Anthony, 1991 ; Dutton, 1991 ; Teymur, 1992 ; Crinson and Lubbock, 1994 ; Salama, 1995 ). It addresses topical concerns that pertain to the goals, objectives, outcomes, structures and contents, as well as the instructional characteristics and delivery and assessment methods and techniques required for responsive and responsible architectural education. Writings from the late 1990s varied including the dynamics of architectural knowledge ( Dunin-Woyseth and Noschis, 1998 ), responding to contemporary professional challenges ( Nicol and Pilling, 2000 ), calling for a revisionist approach to pedagogy ( Salama et al. , 2002 ), delving into a contemporary issues on decision-making, cognitive styles, place-making and digital technologies ( Salama and Wilkinson, 2007 ), articulating cases and successful evidence-based strategies for future teaching practices ( Harriss and Widder, 2014 ; Froud and Harriss, 2015 ; Salama, 2015 ). Emerging research is generating vigorous discussions in the literature. Yet, despite this growing interest in this sphere of inquiry, voluminous research and writings continue to be marginalised within the mainstream research ( Salama, 2015 ) and, therefore, can be characterised as unconventional.

6. Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to contribute an inclusive insight into methodological research in architecture and allied disciplines and to unravel aspects that include philosophical positions, frames of reference and spheres of inquiry. Following ontological and epistemological interpretations, the methodology adopted involved conceptual and critical analysis which is based on reviewing and categorising classical literature and more than hundred contributions in architectural and design research developed over the past five decades which were classified under perspectives of inquiry and frames of reference. Hypothesised through three philosophical positions – positivism, anti-positivism and emancipationist – six frames of reference were identified: systematic, computational, managerial, psychological, person–environment type-A and person–environment type-B. Accentuated by these frames of reference, TOR and CDR were categorised as the perspectives of inquiry, which were scrutinised together with developmental aspects. By mapping the philosophical positions to the frames of reference, various characteristics and spheres of inquiry within each frame of reference were revealed. Additional spheres of inquiry were inferred as branching from the person–environment frame-of-reference: traditional dwellings and settlements research, quality of urban life research, and educational and pedagogical research.

An understanding of the three relatively contradictory philosophical positions is critical. Likewise, an identification of which position will be adopted is crucial when developing a research framework or starting a research activity. While it is imperative that positivistic approaches are valuable and may be used to discover and convey factual knowledge about various aspects of architecture and built environments, it is essential to acknowledge other aspects that affirm the validity of anti-positivist and emancipationist thinking. Consequently, adopting the more inclusive positions places emphasis upon the social, historical and contextual construction of reality: the values, abilities, preferences and lifestyles of the people who use, perceive, and comprehend the built environment. This validates the co-existence of multiple realities and the associated perceptions, and viewpoints.

The analysis of the frames of reference and sphere of inquiry suggests two distinct yet related types of knowledge in architecture and allied disciplines. The first type is knowledge resulting from research that seeks to understand the future through a better understanding of the past; research that tests accepted ideas. The second is knowledge resulting from research that probes new ideas and principles that will shape the future; research that develops new visions and verifies new hypotheses. Within the framework of these knowledge types, it is maintained that the primary objective of methodological research in architecture and allied disciplines is to investigate designs, buildings and built environments made by human beings – designers or non-designers. Implications can be inferred and articulated with respect to key qualities or concerns.

The systematic search and acquisition, assimilation and accommodation of knowledge related to design and design activity, how designers think, approach problems, develop solutions.

The development of expressions, patterns, structures and their organisation into functional wholes.

The physical representation of buildings and environments, how they perform in relation to who sees them and who uses them.

What is achieved at the end of a focused planning or design process, how that which is achieved appears, and what it means to its users and the public at large.

Design and construction processes as human activities, how designers work, how they collaborate with other experts, how they engage with users, how their work speaks to the public and how they carry out these activities.

The systematic learning about the experiences of the past and how these experiences enable the construction of new knowledge.

While the findings developed within this paper enable a more focussed appreciation of methodological research in architecture and allied disciplines, which pertains to the relationship between an adopted philosophical position, a frame of reference and various characteristics of research approaches, further detailed examples can be developed to offer more discerning elucidations relevant to each frame of reference and the spheres of inquiry involved. Within the confines of the analysis provided, the study is viewed as a call for researchers to identify the unique particularities of their research and the way in which it is pursued.

Philosophical positions for research in architecture and allied disciplines

Perspectives and frames of reference within methodological research in architecture and allied disciplines

Mapping frames of reference of methodological research in architecture and allied disciplines to philosophical positions/systems of inquiry

Abdelmonem , M.G. ( 2017 ), “ Architectural and urban heritage in the digital age: dilemmas of authenticity, originality and reproduction ”, Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research , Vol. 11 No. 3 , pp. 5 - 15 .

Akin , O. ( 1986 ), Psychology of Architectural Design , Pion , London .

Akin , O. ( 1987 ), Expertise of the Architect , Carnegie Mellon University , Pittsburgh, PA .

Alexander , C. ( 1964 ), Notes on the Synthesis of form , Harvard University Press , Cambridge, MA .

AlSayyad , N. ( 2014 ), Traditions: the Real, the Hyper, and the Virtual in the Built Environment , Routledge , London .

Altman , I. and Chemers , M. ( 1980 ), Culture and Environment , 1st ed. , Brooks/Cole , Monterey, CA .

Anthony , K.H. ( 1991 ), Design Juries on Trial: the Renaissance of the Design Studio , Van Nostrand Reinhold , New York, NY .

Anumba , C.J. ( 2005 ), Knowledge Management in Construction , Blackwell Publishing , Oxford .

Awan , N. , Schneider , T. and Till , J. ( 2011 ), Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture , Routledge , London .

Blundell-Jones , P. , Petrescu , D. and Till , J. (Eds) ( 2005 ), Architecture and Participation , Taylor & Francis , London .

Broadbent , G. ( 1973 ), Design in Architecture: Architecture and the Human Sciences , John Wiley and Sons , London .

Bordass , B. ( 2001 ), Flying Blind – Everything you wanted to Know about Energy in Commercial Buildings but were Afraid to Ask , Association for the Conservation of Energy , London .

Bordass , B. and Leaman , A. ( 2014 ), “ Building performance evaluation in the UK: so many false dawns ”, in Preiser , W.F.E. , Davis , A.T. , Salama , A.M. and Hardy , A. (Eds), Architecture beyond Criticism: Expert Judgment and Performance Evaluation , Routledge , London , pp. 160 - 170 .

Brown , J.B. , Harriss , H. and Morrow , R. ( 2016 ), A Gendered Profession: the Question of Representation in Space Making , RIBA Publishing , London .

Burgess , P. (Ed.) ( 1983 ), The Role of the Architect in Society , Carnegie Mellon University. , Pittsburgh, PA .

Canter , D.V. ( 1974 ), Psychology for Architects , Applied Science , London .

Canter , D.V. ( 1977 ), The Psychology of Place , St Martin’s Press , New York, NY .

Casakin , H. and Kreitler , S. ( 2011 ), “ The cognitive profile of creativity in design ”, Thinking Skills and Creativity , Vol. 6 No. 3 , pp. 159 - 168 .

Cooper , R. ( 2010 ), Wayfinding for Health Care: Best Practices for Today’s Facilities , AHA Press/Health Forum , Chicago, IL .

Crinson , M. and Lubbock , J. ( 1994 ), Architecture–Art or profession?: Three Hundred Years of Architectural Education in Britain , Manchester University Press , Manchester .

Cross , N. ( 2016 ), Design Thinking: Understanding how Designers Think and Work , Bloomsbury , London .

Cross , N. (Ed.) ( 1984 ), Developments in Design Methodology , Wiley , Chichester .

Cuff , D. ( 1991 ), Architecture: the Story of Practice , The MIT Press , Cambridge, MA .

Darbellay , F. , Moody , Z. and Lubart , T. ( 2018 ), Creativity, Design Thinking and Interdisciplinarity , Springer , Singapore .

de Dear , R. , Kim , J. and Parkinson , T. ( 2018 ), “ Residential adaptive comfort in a humid subtropical climate – Sydney Australia ”, Energy and Buildings , Vol. 158 , January , pp. 1296 - 1305 .

Denzin , N.K. and Lincoln , Y.S. (Eds) ( 2000 ), Handbook of Qualitative Research , Sage Publications , Thousand Oaks, CA .

Duffy , F. ( 2014 ), “ Buildings and their use: the dog that didn't bark ”, in Preiser , W.F.E. , Davis , A.T. , Salama , A.M. and Hardy , A. (Eds), Architecture Beyond Criticism: Expert Judgment and Performance Evaluation , Routledge , London , pp. 128 - 132 .

Dunin-Woyseth , H. and Noschis , K. (Eds) ( 1998 ), Architecture and Teaching: Epistemological Foundations , Comportements , Lausanne .

Dutton , T.A. (Ed.) ( 1991 ), Voices in Architectural Education: Cultural Politics and Pedagogy , Bergin and Garvey , New York, NY .

Dye , A. (Ed.) ( 2014 ), How Architects Use Research – Case Studies from Practice , RIBA , London .

Eastman , C.M. ( 1969 ), “ Cognitive processes and ill-defined problems: a case study from design ”, Proceeding IJCAI’69 Proceedings of the 1st International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence , Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc. , San Francisco, CA , pp. 669 - 690 .

Emmitt , S. , Prins , M. and Otter , A. (Eds) ( 2009 ), Architectural Management: International Research and Practice , Wiley-Blackwell , Chichester .

Fisher , T. ( 2010 ), Ethics for Architects: 50 Dilemmas of Professional Practice , Princeton Architectural Press , Princeton, NJ .

Fisher , T.R. ( 2006 ), In the Scheme of Things: Alternative Thinking on the Practice of Architecture , University of Minnesota Press , Minneapolis, MN .

Franz , J.M. ( 1994 ), “ A critical framework for methodological research in architecture ”, Design Studies , Vol. 15 No. 4 , pp. 433 - 447 .

Fraser , M. (Ed.) ( 2013 ), Design Research in Architecture: An Overview , Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group , London .

Froud , D. and Harriss , H. (Eds) ( 2015 ), Radical Pedagogies Architectural Education and the British Tradition , RIBA Publishing , London .

Gero , J.S. ( 1983 ), “ Computer-aided architectural design – past, present and future ”, Architectural Science Review , Vol. 26 No. 1 , pp. 2 - 5 .

Gero , J.S. and Maher , M.L. ( 1993 ), Modeling Creativity and Knowledge-Based Creative Design , Lawernce Erlbaum , Hillsdale, NJ .

Goldschmidt , G. ( 1989 ), “ Problem representation versus domain of solution in architectural design education ”, Journal of Architectural and Planning Research, Special Issue: Architectural Education for Architectural Practice , Vol. 6 No. 3 , pp. 204 - 215 .

Goldschmidt , G. ( 2014 ), Linkography: Unfolding the Design Process , The MIT Press , Cambridge, MA .

Goulding , J.S. and Rahimian , F.P. ( 2015 ), “ Design creativity: future directions for integrated visualisation ”, Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research , Vol. 9 No. 3 , pp. 1 - 5 .

Groat , L. and Wang , D. ( 2002 ), Architectural Research Methods , John Wiley , New York, NY .

Gutman , R. ( 1975 ), “ The place of architecture in sociology ”, Research Center for Urban and Environmental Planning, School of Architecture and Urban Planning, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ .

Gutman , R. ( 1988 ), Architectural Practice: A Critical View , Princeton Architectural Press , Princeton, NJ .

Hamdi , N. ( 1990 ), Housing without Houses: Participation, Flexibility, Enablement , Van Nostrand Reinhold , New York, NY .

Hamilton , D.K. and Watkins , D.H. ( 2009 ), Evidence-Based Design for Multiple Building Types , Wiley , Hoboken, NJ .

Harriss , H. and Widder , L. (Eds) ( 2014 ), Architecture live Projects: Pedagogy into Practice , Routledge , London .

Heath , T. ( 1984 ), Method in Architecture , Wiley , Chichester .

Hensel , M.U. ( 2010 ), “ Performance-oriented architecture: towards a biological paradigm for architectural design and the built environment ”, FORMakademisk , Vol. 3 No. 1 , pp. 36 - 56 .

Hershberger , R.G. ( 1999 ), Architectural Programming and Predesign Manager , McGraw-Hill , New York, NY .

Hester , R.T. ( 1990 ), Community Design Primer , Ridge Times Press , Mendocino, CA .

Hillier , B. ( 2015 ), Space is the Machine: a Configurational Theory of Architecture , CreateSpace – Independent Publishing Platform , London .

Hillier , B. and Hanson , J. ( 1984 ), The Social Logic of Space , Cambridge University Press , Cambridge .

IAPS ( 2018 ), “ Transitions to sustainability, lifestyles changes, and human wellbeing ”, Proceedings of the 25th IAPS Conference, IAPS , Rome .

James , P. ( 2015 ), Urban Sustainability in Theory and Practice: Circles of Sustainability , Routledge , London .

Jenkins , P. and Forsyth , L. ( 2009 ), Architecture, Participation and Society , Routledge , London .

Kumar , B. ( 2015 ), A Practical Guide to Adopting BIM in Construction Projects , Whittles Publishing , Caithness .

Kumar , B. ( 2018 ), Contemporary Strategies and Approaches in 3-D Information Modelling , IGI Global , Hershey, PA .

Lawrence , R. ( 1987 ), Housing, Dwellings and Homes: Design theory, Research and Practice , John Wiley & Sons , Chichester .

Lawson , B. ( 1980 ), How Designers Think: the Design Process Demystified , Architectural Press , London .

Lawson , B. ( 2015 ), “ Book review: Design Research in Architecture: An Overview ”, Design Studies , Vol. 36 , January , pp. 125 - 130 .

Lincoln , Y.S. , Lynham , S.A. and Guba , E.G. ( 2011 ), “ Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences, revisited ”, in Denzin , N.K. and Lincoln , Y.S. (Eds), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research , Sage , Thousand Oaks, CA , pp. 97 - 128 .

Lucas , R. ( 2016 ), Research Methods for Architecture , Laurence King Publishing , London .

Mallory-Hill , S. , Preiser , W.F.E. and Watson , C. (Eds) ( 2012 ), Enhancing Building Performance , Wiley-Blackwell , Chichester .

Malone , L. ( 2018 ), Desire Lines: a Guide to Community Participation in Designing Places , RIBA Publishing , London .

Marans , R. and Stimson , R. (Eds), ( 2011 ), Investigating Quality of Urban Life: Theory, Methods, and Empirical Research , Springer , New York, NY .

Marans , R.W. ( 2012 ), “ Quality of urban life studies: an overview and implications for environment–behaviour research ”, Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences , Vol. 35 , pp. 9 - 22 .

Marcus , C.C. ( 1972 ), Resident Dissatisfaction in Multi-Family Housing , University of California, Institute of Urban and Regional Development , Berkeley, CA .

Marcus , C.C. ( 1985 ), Design Guidelines: A Bridge between Research and Decision-Making , Center for Environmental Design Research, University of California , Berkeley, CA .

Markus , T.A. ( 1972 ), Building Performance , John Wiley & Sons , New York, NY .

Maver , T. ( 1971 ), “ Computer aided building appraisal ”, Architects Journal , July , pp. 207 - 214 .

Mitchell , W.J. ( 1979 ), Computer-Aided Architectural Design , Van Nostrand Reinhold , New York, NY .

Mitchell , W.J. ( 1990 ), The Logic of Architecture: Design, Computation, and Cognition , The MIT Press , Cambridge, MA .

Nasar , J.L. ( 1988 ), Environmental Aesthetics: Theory, Research, Applications , Cambridge University Press , New York, NY .

Newell , A. and Simon , H.A. ( 1972 ), Human Problem Solving , Prentice-Hall , Englewood Cliffs, NJ .

Nicol , D. and Pilling , S. (Eds) ( 2000 ), Changing Architectural Education Towards a New Professionalism , E & FN Spon , London .

Norton , P. and Hughes , M. ( 2018 ), Public Consultation and Community Involvement in Planning a Twenty-First Century Guide , Routledge , London .

OED ( 2012 ), Oxford English Dictionary , Oxford University Press , Oxford .

Oxman , R. ( 2017 ), “ Thinking difference: theories and models of parametric design thinking ”, Design Studies , Vol. 52 , September , pp. 4 - 39 .

Passini , R. ( 1992 ), Wayfinding in Architecture , Van Nostrand Reinhold , New York, NY .

Preiser , W.F.E. (Ed.) ( 1985 ), Programming the Built Environment , Van Nostrand Reinhold , New York, NY .

Preiser , W.F.E. and Nasar , J.L. ( 2008 ), “ Assessing building performance: its evolution from post-occupancy evaluation ”, Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research , Vol. 2 No. 1 , pp. 84 - 99 .

Preiser , W.F.E. and Vischer , J. (Eds) ( 2012 ), Assessing Building Performance , Routledge , New York, NY .

Preiser , W.F.E. , Rabinowitz , H.Z. and White , E.T. ( 1988 ), Post-Occupancy Evaluation , Van Nostrand Reinhold , New York, NY .

Preiser , W.F.E. , Davis , A.T. , Salama , A.M. and Hardy , A. (Eds) ( 2014 ), Architecture beyond Criticism: Expert Judgment and Performance Evaluation , Routledge , London .

Proshansky , H.M. ( 1990 ), “ The pursuit of understanding ”, in Altman , I. and Christensen , K. (Eds), Environment and Behavior Studies: Emergence of Intellectual Traditions , Plenum Press , New York, NY , pp. 9 - 30 .

Rapoport , A. ( 1969 ), House form and Culture , Prentice-Hall , Englewood Cliffs, NJ .

Rapoport , A. ( 1977 ), Human Aspects of Urban form: Towards a Man-Environment Approach to Urban form and Design , Pergamon Press , Toronto .

Rapoport , A. ( 1990 ), The Meaning of the Built Environment: A Nonverbal Communication Approach , The University of Arizona Press , Tucson, AZ .

Rapoport , A. ( 2005 ), Culture, Architecture, and Design , Locke Science Publishing , Chicago, IL .

Rapoport , A. ( 2008 ), “ Some further thoughts on culture and environment ”, Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research , Vol. 2 No. 1 , pp. 16 - 39 .

Rittel , H.W.J. and Webber , M.M. ( 1973 ), “ Dilemmas in a general theory of planning ”, Policy Sciences , Vol. 4 No. 2 , pp. 155 - 169 .

Roaf , S. , Brotas , L. and Nicol , F. (Eds) ( 2017 ), PLEA 2017 Legacy Document of 33rd PLEA International Conference – Design to Thrive , PLEA , Edinburgh .

Rowe , P.G. ( 1987 ), Design Thinking , MIT Press , Cambridge, MA .

Sacks , R. , Eastman , C.M. , Lee , G. and Teicholz , P.M. ( 2018 ), BIM Handbook: A Guide to Building Information Modeling for Owners, Designers, Engineers, Contractors, and Facility Managers , Wiley , Hoboken, NJ .

Salama , A.M. ( 1995 ), New Trends in Architectural Education: Designing the Design Studio , Tailored Text Publishers , Raleigh, NC .

Salama , A.M. ( 1998 ), “ A new paradigm in architectural pedagogy: integrating environment-behavior studies into architectural education teaching practices ”, in Teklenburg , J. , van Andel , J. , Smeets , J. and Seidel , A. (Eds), IAPS 15th – Shifting Balances: Changing Roles in Policy, Research and Design , EIRASS Publishers , Eindhoven , pp. 128 - 139 .

Salama , A.M. ( 2008 ), “ A theory for integrating knowledge in architectural design education ”, ArchNet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research , Vol. 2 No. 1 , pp. 100 - 128 .

Salama , A.M. ( 2012 ), “ Knowledge and design: people–environment research for responsive pedagogy and practice ”, Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences , Vol. 49 , pp. 8 - 27 .

Salama , A.M. ( 2015 ), Spatial Design Education: New Directions for Pedagogy in Architecture and Beyond : Routledge , London .

Salama , A.M. and Wilkinson , N. (Eds) ( 2007 ), Design Studio Pedagogy: Horizons for the Future , The Urban International Press , Gateshead .

Salama , A.M. , O’Reilly , W. and Noschis , K. (Eds) ( 2002 ), Architectural Education Today: Cross Cultural Perspectives , Comportements , Lausanne .

Samuel , F. and Dye , A. ( 2015 ), Demystifying Architectural Research: Adding Value to your Practice , RIBA Publishing , London .

Sanoff , H. ( 1977 ), Methods of Architectural Programming , Dowden, Hutchinson & Ross , Stroudsburg, PA .

Sanoff , H. ( 1978 ), Designing with Community Participation , McGraw Hill , New York, NY .

Sanoff , H. ( 1984 ), Design Games , Kaufmann , Los Altos, CA .

Sanoff , H. ( 1991 ), Visual Research Methods in Design , Van Nostrand Reinhold , New York, NY .

Sanoff , H. ( 1992 ), Integrating Programming, Evaluation and Participation in Design: A Theory Z Approach , Avebury/Ashgate , Hampshire .

Sanoff , H. ( 2000 ), Community Participation Methods in Design and Planning , John Wiley & Sons , New York, NY .

Sanoff , H. ( 2010 ), Democratic Design: Participation Case Studies in Urban and Small Town Environments , VDM Verlag Dr. Müller , Saarbrücken .

Shin , J.-H. , Narayan , M. and Dennis , S. (Eds) ( 2017 ), Voices of Place: Empower, Engage, Energize: Proceedings of the 48th Annual Conference of the Environmental Design Research Association , EDRA , Madison, WI .

Simon , H.A. ( 1973 ), “ The structure of ill structured problems ”, Artificial Intelligence , Vol. 4 Nos 3-4 , pp. 181 - 201 .

Teymur , N. ( 1992 ), Architectural Education: Issues in Educational Policies and Practice , Question Press , London .

Thomas , J.C. and Carroll , J.M. ( 1979 ), The Psychological Study of Design , IBM Thomas J. Watson Research Division , San Jose, CA .

Till , J. ( 2013 ), Architecture depends , MIT Press , Cambridge, MA .

Wade , J.W. ( 1977 ), Architecture, Problems and Purposes: Architectural Design as a Basic Problem-Solving Process , Wiley , Chichester .

Wessels , T. ( 2013 ), The Myth of Progress: Toward a Sustainable Future , University Press of New England , Lebanon, NH .

Whitehead , B. and Eldars , M. ( 1965 ), “ The planning of single-storey layouts ”, Building Science , Vol. 1 No. 2 , pp. 127 - 139 .

Whyte , J. and Nikolic , D. ( 2018 ), Virtual Reality and the Built Environment , Routledge , London .

Whyte , W.H. ( 1980 ), The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces , Project for Public Spaces , Washington, DC .

Zuo , J. , Daniel , L. and Soebarto , V. (Eds) ( 2016 ), Proceedings of the 50th International Conference of the Architectural Science Association. Revisiting the Role of Architectural Science in Design and Practice , School of Architecture and Built Environment, The University of Adelaide , Adelaide .

Corresponding author

About the author.

Professor Ashraf M. Salama is the Editor-in-Chief of Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research . He is an internationally renowned academic and the 2017 UIA recipient of Jean Tschumi Prize, of the International Union of Architects, for excellence in architectural education and criticism. Professor Salama is the Author and Co-editor of ten books and numerous research papers published in the international peer-reviewed press. He is Chair Professor in Architecture and Head of the Department of Architecture, University of Strathclyde Glasgow, UK.

Related articles

All feedback is valuable.

Please share your general feedback

Report an issue or find answers to frequently asked questions

Contact Customer Support

#Mission2.0 is here to disrupt the mundane. Are you? Join Now

- BIM Professional Course for Architects

- Master Computational Design Course

- BIM Professional Course For Civil Engineers

- Hire From Us

Request a callback

- Architecture & Construction

- Computational Design

- Company News

- Expert Talks

Writing an Architecture Thesis: A-Z Guide

ishika kapoor

14 min read

January 5, 2022

Table of Contents

How to Choose Your Architecture Thesis Topic

As with most things, taking the first step is often the hardest. Choosing a topic for your architecture thesis is not just daunting but also one that your faculty will not offer much help with. To aid this annual confusion among students of architecture, we've created this resource with tips, topics to choose from, case examples, and links to further reading!

[Read: 7 Tips on Choosing the Perfect Architecture Thesis Topic for you ]

1. What You Love

Might seem like a no-brainer, but in the flurry of taking up a feasible topic, students often neglect this crucial point. Taking up a topic you're passionate about will not just make for a unique thesis, but will also ensure your dedication during tough times.

Think about the things you're interested in apart from architecture. Is it music? Sports? History? Then, look for topics that can logically incorporate these interests into your thesis. For example, I have always been invested in women's rights, and therefore I chose to design rehabilitation shelters for battered women for my thesis. My vested interest in the topic kept me going through heavy submissions and nights of demotivation!

Watch Vipanchi's video above to get insights on how she incorporated her interest in Urban Farming to create a brilliant thesis proposal, which ended up being one of the most viewed theses on the internet in India!

2. What You're Good At

You might admire, say, tensile structures, but it’s not necessary that you’re also good at designing them. Take a good look at the skills you’ve gathered over the years in architecture school- whether it be landscapes, form creation, parametric modelling- and try to incorporate one or two of them into your thesis.

It is these skills that give you an edge and make the process slightly easier.

The other way to look at this is context-based , both personal and geographical. Ask yourself the following questions:

• Do you have a unique insight into a particular town by virtue of having spent some time there?

• Do you come from a certain background , like doctors, chefs, etc? That might give you access to information not commonly available.

• Do you have a stronghold over a particular built typology?

3. What the World Needs

By now, we’ve covered two aspects of picking your topic which focus solely on you. However, your thesis will be concerned with a lot more people than you! A worthy objective to factor in is to think about what the world needs which can combine with what you want to do.

For example, say Tara loves photography, and has unique knowledge of its processes. Rather than creating a museum for cameras, she may consider a school for filmmaking or even a film studio!

Another way to look at this is to think about socio-economically relevant topics, which demonstrate their own urgency. Think disaster housing, adaptive reuse of spaces for medical care, etcetera. Browse many such categories in our resource below!

[Read: 30 Architecture Thesis Topics You Can Choose From ]

4. What is Feasible

Time to get real! As your thesis is a project being conducted within the confines of an institution as well as a semester, there are certain constraints which we need to take care of:

• Site/Data Accessibility: Can you access your site? Is it possible to get your hands on site data and drawings in time?

• Size of Site and Built-up Area: Try for bigger than a residential plot, but much smaller than urban scale. The larger your site/built-up, the harder it will be to do justice to it.

• Popularity/Controversy of Topic: While there’s nothing wrong with going for a popular or controversial topic, you may find highly opinionated faculty/jury on that subject, which might hinder their ability to give unbiased feedback.

• Timeline! Only you know how productive you are, so go with a topic that suits the speed at which you work. This will help you avoid unnecessary stress during the semester.

How to Create an Area Program for your Architecture Thesis

Watch SPA Delhi Thesis Gold-Medallist Nishita Mohta talk about how to create a good quality area program.

Often assumed to be a quantitative exercise, creating an area program is just as much a qualitative effort. As Nishita says, “An area program is of good quality when all user experiences are created with thought and intention to enhance the usage of the site and social fabric.”

Essentially, your area program needs to be human-centric, wherein each component is present for a very good reason. Rigorously question the existence of every component on your program for whether it satisfies an existing need, or creates immense value for users of your site.

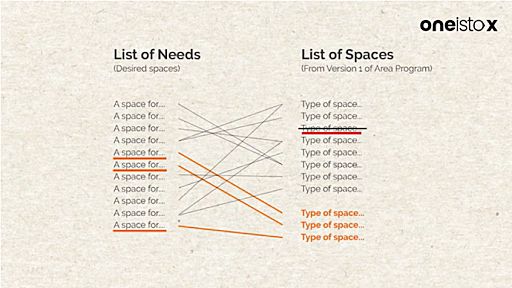

To this end, you need to create three lists:

• A list of proposed spaces by referring to area programs of similar projects;

• A list of needs of your users which can be fulfilled by spatial intervention.

• A list of existing functions offered by your immediate context.

Once you put these lists side-by-side, you’ll see that you are able to match certain needs of users to some proposed spaces on your list, or to those in the immediate context.

However, there will be some proposed spaces which do not cater to any need, and needs that are not catered to by any of the spaces. There will also be certain proposed spaces which are redundant because the context already fulfils that need.

This when you remove redundant spaces to create ones for unmatched needs, and viola, you have a good quality area program!

Confused? Here’s an example from the above video. Nishita originally intended to provide a typical eatery on her site, which she later realised was redundant because several eateries already existed around it. In this manner, she was able to fulfil the actual needs of her users- one of which was to be able to rest without having to pay for anything- rather than creating a generic, unnecessary space.

How to Identify Key Stakeholders for Your Architecture Thesis

“A stakeholder? You mean investors in my thesis?”, you scoff.

You’re not wrong! Theoretically, there are several people invested in your thesis! A stakeholder in an architectural project is anyone who has interest and gets impacted by the process or outcome of the project.

At this point, you may question why it’s important to identify your stakeholders. The stakeholders in your thesis will comprise of your user groups, and without knowing your users, you can’t know their needs or design for them!

There are usually two broad categories of stakeholders you must investigate:

• Key Stakeholders: Client and the targeted users

• Invisible Stakeholders: Residents around the site, local businesses, etc.

Within these broad categories, start by naming the kind of stakeholder. Are they residents in your site? Visitors? Workers? Low-income neighbours? Once you’ve named all of them, go ahead and interview at least one person from each category!

The reason for this activity is that you are not the all-knowing Almighty. One can never assume to know what all your users and stakeholders need, and therefore, it’s essential to understand perspectives and break assumptions by talking directly to them. This is how you come up with the aforementioned 'List of Needs', and through it, an area program with a solid footing.

An added advantage of carrying out this interviewing process is that at the end of the day, nobody, not even the jury, can question you on the relevance of a function on your site!

Why Empathy Mapping is Crucial for Your Architecture Thesis

Okay, I interviewed my stakeholders, but I can’t really convert a long conversation into actionable inputs. What do I do?

This is where empathy mapping comes in. It basically allows you to synthesize your data and reduce it to the Pain Points and Gain Points of your stakeholders, which are the inferences of all your observations.

• Pain Points: Problems and challenges that your users face, which you should try to address through design.

• Gain Points: Aspirations of your users which can be catered to through design.

In the above video, Nishita guides you through using an empathy map, so I would highly recommend our readers to watch it. The inferences through empathy mapping are what will help you create a human-centric design that is valuable to the user, the city, and the social fabric.

Download your own copy of this Empathy Map by David Gray , and get working!

Beyond Case Studies: Component Research for your Architecture Thesis

Coming to the more important aspects, it’s essential to know whether learning a new skill will expand your employability prospects. Otherwise, might as well just spend the extra time sleeping. Apart from being a highly sought-after skill within each design field, Rhinoceros is a unique software application being used across the entire spectrum of design. This vastly multiples your chances of being hired and gives you powerful versatility as a freelancer or entrepreneur. The following are some heavyweights in the design world where Rhino 3D is used:

Case Studies are usually existing projects that broadly capture the intent of your thesis. But, it’s not necessary that all components on your site will get covered in depth during your case studies.', 'Instead, we recommend also doing individual Component (or Typology) Research, especially for functions with highly technical spatial requirements.

For example, say you have proposed a residence hall which has a dining area, and therefore, a kitchen- but you have never seen an industrial kitchen before. How would you go about designing it?', 'Not very well!', 'Or, you’re designing a research institute with a chemistry lab, but you don’t know what kind of equipment they use or how a chem lab is typically laid out.

But don’t freak out, it’s not necessary that all of this research needs to be in person! You can use a mixture of primary and secondary studies to your advantage. The point of this exercise is to deeply understand each component on your site such that you face lesser obstacles while designing.

[Read: Site Analysis Categories You Need to Cover For Your Architecture Thesis Project ]" ]

The Technique of Writing an Experiential Narrative for your Architecture Thesis

A narrative? You mean writing? What does that have to do with anything?

A hell of a lot, actually! While your area programs, case studies, site analysis, etc. deal with the tangible, the experience narrative is about the intangible. It is about creating a story for what your user would experience as they walk through the space, which is communicated best in the form of text. This is done for your clarity before you start designing, to be your constant reference as to what you aim to experientially achieve through design.

At the end of the day, all your user will consciously feel is the experience of using your space, so why not have a clear idea of what we want to achieve?

This can be as long or as short as you want, it’s completely up to you! To get an example of what an experience narrative looks like, download the ebook and take a look at what Nishita wrote for her thesis.

Overcoming Creative Blocks During Your Architecture Thesis

Ah, the old enemy of the artist, the Creative Block. Much has been said about creative blocks over time, but there’s not enough guidance on how to overcome them before they send your deadline straight to hell.

When you must put your work out into the world for judgement, there is an automatic fear of judgement and failure which gets activated. It is a defensive mechanism that the brain creates to avoid potential emotional harm.

So how do we override this self-destructive mechanism?

As Nishita says, just waiting for the block to dissolve until we magically feel okay again is not always an option. Therefore, we need to address the block there and then, and to systematically seek inspiration which would help us with a creative breakthrough.

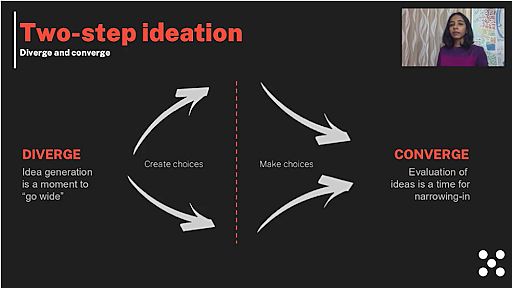

This is where the concept of Divergent and Convergent Thinking comes in.

• Divergent Thinking: Say you browse through ideas on pinterest to get inspired. If you’re in a creative rut, do just that, but don’t worry about implementing any of those ideas. Freely and carelessly jot down everything that inspires you right now regardless of how unfeasible they may be. This is called Divergent Thinking! This process will help unclog your brain and free it from anxiety.

Divergent and convergent thinking.

• Convergent Thinking: Now, using the various constraints of your architecture thesis project, keep or eliminate those ideas based on how feasible they are for your thesis. This is called Convergent Thinking. You’ll either end up with some great concepts to pursue, or have become much more receptive to creative thinking!

Feel free to use Nishita’s Idea Dashboard (example in the video) to give an identity to the ideas you chose to go forward with. Who knows, maybe your creative block will end up being what propels you forward in your ideation process!

How to Prototype Form and Function During Your Architecture Thesis

Prototyping is one of the most crucial processes of your architecture thesis project. But what exactly does it mean?

“A preliminary version of your designed space which can be used to give an idea of various aspects of your space is known as a prototype.”

As Nishita explains in the video above, there can be endless kinds of prototypes that you can explore for your thesis, and all of them explain different parts of your designed space. However, the two aspects of your thesis most crucial to communicate through prototyping are Form and Function.

As we know, nothing beats physical or 3D models as prototypes of form. But how can you prototype function? Nishita gives the example of designing a School for the Blind , wherein you can rearrange your actual studio according to principles you’re using to design for blind people. And then, make your faculty and friends walk through the space with blindfolds on! Prototyping doesn’t get better than this.

In the absence of time or a physical space, you may also explore digital walkthroughs to achieve similar results. Whatever your method may be, eventually the aim of the prototype is to give a good idea of versions of your space to your faculty, friends, or jury, such that they can offer valuable feedback. The different prototypes you create during your thesis will all end up in formulating the best possible version towards the end.

Within the spectrum of prototypes, they also may vary between Narrative Prototypes and Experiential Prototypes. Watch the video above to know where your chosen methods lie on this scale and to get more examples of fascinating prototyping!

How to Convert Feedback (Crits) into Action During Your Architecture Thesis Project

Nishita talks about how to efficiently capture feedback and convert them into actionable points during your architecture thesis process.

If you’ve understood the worth of prototyping, you would also know by now that those prototypes are only valuable if you continuously seek feedback on them. However, the process of taking architectural ‘crits’ (critique) can often be a prolonged, meandering affair and one may come out of them feeling dazed, hopeless and confused. This is especially true for the dreaded architecture thesis crits!

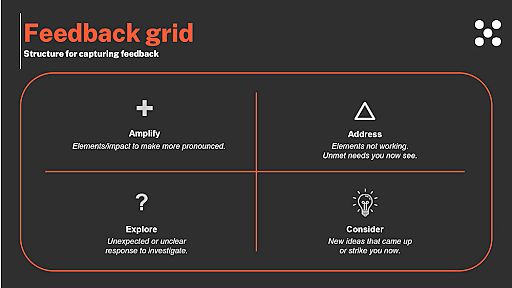

To avoid that, Nishita suggests capturing feedback efficiently in a simple grid, noting remarks under the following four categories:

• Amplify: There will be certain aspects of your thesis that your faculty and friends would appreciate, or would point out as key features of your design that must be made more prominent. For example, you may have chosen to use a certain definitive kind of window in a space, which you could be advised to use more consistently across your design. This is the kind of feedback you would put under ‘Amplify’.

• Address: More often, you will receive feedback which says, ‘this is not working’ or ‘you’ve done nothing to address this problem’. In such cases, don’t get dejected or defensive, simply note the points under the ‘Address’ column. Whether you agree with the advice or not, you cannot ignore it completely!

• Explore: Sometimes, you get feedback that is totally out of the blue or is rather unclear in its intent. Don’t ponder too long over those points during your crit at the cost of other (probably more important) aspects. Rather, write down such feedback under the ‘Explore’ column, to investigate further independently.

• Consider: When someone looks at your work, their creative and problem-solving synapses start firing as well, and they are likely to come up with ideas of their own which you may not have considered. You may or may not want to take them up, but it is a worthy effort to put them down under the ‘Consider’ column to ruminate over later!

Following this system, you would come out of the feedback session with action points already in hand! Feel free to now go get a coffee, knowing that you have everything you need to continue developing your architecture thesis project.

How to Structure Your Architecture Thesis Presentation for a Brilliant Jury

And so, together, we have reached the last stage of your architecture thesis project: The Jury. Here, I will refrain from telling you that this is the most important part of the semester, as I believe that the process of learning is a lot more valuable than the outcome. However, one cannot deny the satisfaction of a good jury at the end of a gruelling semester!

Related Topics

- Architecture and Construction

- design careers

- future tech

Subscribe to Novatr

Always stay up to date with what’s new in AEC!

Get articles like these delivered to your inbox every two weeks.

Related articles

.png)

Everything You Need to Know About Rhino 3D

September 6, 2022

15 min read

How Rhino Grasshopper is used in Parametric Designs & Modelling

Bandana Singh

May 27, 2024

11 min read

Rhino 3D v/s Solidworks: Which Software is Best to Learn In 2024?

April 30, 2024

10 min read

Top 7 Rhino and Grasshopper Online Courses to Get Started with Parametric Modelling

September 7, 2022

Ready to skyrocket your career?

Your next chapter in AEC begins with Novatr!

As you would have gathered, we are here to help you take the industry by storm with advanced, tech-first skills.

Dare to Disrupt.

Join thousands of people who organise work and life with Novatr.

Join our newsletter

We’ll send you a nice letter once per week. No spam.

- Become a Mentor

- Careers at Novatr

- Events & Webinars

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

©2023 Novatr Network Pvt. Ltd.

All Rights Reserved

Different Types of Methodologies Used For Dissertations in Architecture