Arguments and Information

Learning Objectives

- Define what an argument is

- Introduce ethos, pathos, and logos

- Identify the argument structure of claim, evidence, and warrant

- Explore effective language

You may be wondering, “What exactly is an argument? Haven’t I already decided on my main argument and topic?”

An argument is a series of statements in support of a claim, assertion, or proposition. So far, we’ve discussed thesis statements as the main argumentative through-line for a speech—it’s what you want to inform, persuade, or entertain the audience about.

Your thesis statement, however, is just one component of an argument, i.e. “here’s what I want to inform you about / persuade you to consider.” It is the main claim of your speech. Your task is to prove the reliability of that claim (with evidence) and demonstrate, through the body of the speech, how or why that information should matter to the audience. In this chapter, we will fill in the other structural components of an argument to make sure that your thesis statement has adequate support and proof. We’ll also outline the importance of language and tips to guarantee that your language increases the effective presentation of your argument.

An Overview of Arguments

It may be tempting to view arguments as only relevant to persuasion or persuasive speeches. After all, we commonly think of arguments as occurring between different perspectives or viewpoints with the goal of changing someone’s mind. Arguments are important when persuading (and we will re-visit persuasive arguments in Chapter 13), but you should have clear evidence and explanations for any type of information sharing.

All speech types require proof to demonstrate the reliability of their claims. Remember, when you speak, you are being an advocate and selecting information that you find relevant to your audience, so arguments are necessary to, at a bare minimum, build in details about the topic’s importance.

With speeches that primarily inform, a sound argument demonstrates the relevance and significance of the topic for your audience. In other words, “this is important information because…” or “here’s why you should care about this.” If you are giving a ceremonial speech, you should provide examples of your insights. In a speech of introduction, for example, you may claim that the speaker has expertise, but you should also provide evidence of their previous accomplishments and demonstrate why those accomplishments are significant.

For each speech type, a well-crafted speech will have multiple arguments throughout. Yes, your thesis statement is central to speech, and your content should be crafted around that idea – you will use your entire speech to prove the reliability of that statement. You will also have internal arguments, i.e. your speech’s main points or the “meat” of your speech.

All speech types require arguments, and all arguments use the rhetorical appeals of ethos, pathos, and logos to elicit a particular feeling or response from your audience.

Ethos , or establishing your credibility as a speaker, is necessary for any speech. If you’re informing the audience about a key topic, they need to know that you’re a trustworthy and reliable speaker. A key way to prove that credibility is through crafting arguments that are equally credible. Using reliable and well-tested evidence is one way to establish ethos.

Using reason or logic, otherwise known as logos , is also a key rhetorical appeal. By using logos, you can select logical evidence that is well-reasoned, particularly when you’re informing or persuading. We’ll talk more about logic and fallacies (to avoid) in Chapter 13.

Pathos , or emotional appeals, allows you to embed evidence or explanations that pull on your audience’s heartstrings or other feelings and values. Pathos is common in ceremonial speeches, particularly speeches that eulogize or celebrate a special occasion.

All three rhetorical appeals are important mechanisms to motivate your audience to listen or act. All three should be done ethically (see Chapter 1) and with the speech context and audience in mind.

Regardless of which rhetorical proof you use, your arguments should be well-researched and well-structured. Below, we explore the structure of an argument in more detail.

The Structur e : Claim, Evidence, Warrant

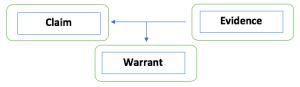

Arguments have the following basic structure (see Figure 5.1):

- Claim: the main proposition crafted as a declarative statement.

- Evidence: the support or proof for the claim.

- Warrant: the connection between the evidence and the claim.

Each component of the structure is necessary to formulate a compelling argument.

The Toulmin Model

British Philosopher, Stephen Toulmin, created the “Toulmin Model” – a model that describes the structure of an argument or method of reasoning. Claim, evidence, and warrant are, if done well, necessary to create a good argument (O’Connor, 1958).

Evidence and warrants are the specifics that make your ideas, arguments, assertions, points, or concepts real and concrete by relating the information to your audience. Not all audiences are compelled by the same evidence, for example, so creating a well-structured argument also means being responsive to audiences.

Consider going to lunch with a friend. Your friend suggests a restaurant that you have not heard of, so you request some additional information, proof, or evidence of their choice. We could map the argument like this:

- Claim: “Let’s go to Jack’s Shack for lunch.”

- Evidence: “I have been there a few times and they have good servers.”

So far, your friend is highlighting service as the evidence to support their claim that Jack’s Shack is a good choice for lunch. However, the warrant is still missing. For a warrant, they need to demonstrate why good service is sufficient proof to support their claim. Remember that the warrant is the connection. For example:

- Warrant: “You were a server, so I know that you really appreciate good service. I have never had a bad experience at Jack’s Shack, so I am confident that it’s a good lunch choice for both of us.”

In this case, they do a good job of both connecting the evidence to the claim and connecting the argument to their audience – you! They have selected evidence based on your previous experience as a server (likely in hopes to win you over to their claim!).

Using “claim, evidence, and warrant” can assist you in verifying that all parts of the argumentative structure are present. Below, we dive deeper into each category.

A claim is a declarative statement or assertion—it is something that you want your audience to accept or know. Like we’ve mentioned, your thesis statement is a key claim in your speech because it’s the main argument that you’re asking the audience to consider.

Different claims serve different purposes. Depending on the purpose of the argument, claims can be factual, opinionated, or informative. Some claims, for example, may be overtly persuading the audience to change their mind about a controversial issue, i.e. “you should support this local policy initiative.”

Alternatively, a claim may develop the significance of a topic (i.e. “this is why you should care about this information”) or highlight a key informative component about a person, place, or thing (“Hillary Clinton had an intriguing upbringing”). You might, for example, write a speech that informs the audience about college textbook affordability. Your working thesis might read, “Universities are developing textbook affordability initiatives.” Your next step would be to develop main points and locate evidence that supports your claim.

It’s important to develop confidence around writing and identifying your claims. Identifying your main ideas will allow you to then identify evidence in support of those declarative statements. If you aren’t confident about what claims you’re making, it will be difficult to identify the evidence in support of that idea, and your argument won’t be structurally complete. Remember that your thesis statement your main claim, but you likely have claims throughout your speech (like your main points).

Evidence is the proof or support for your claim. It answers the question, “how do I know this is true?” With any type of evidence, there are three overarching considerations.

First, is this the most timely and relevant type of support for my claim? If your evidence isn’t timely (or has been disproven), it may drastically influence the credibility of your claim.

Second, is this evidence relatable and clear for my audience? Your audience should be able to understand the evidence, including any references or ideas within your information. Have you ever heard a joke or insight about a television show that you’ve never seen? If so, understanding the joke can be difficult. The same is true for your audience, so stay focused on their knowledge base and level of understanding.

Third, did I cherry-pick? Avoid cherry-picking evidence to support your claims. While we’ve discussed claims first, it’s important to arrive at a claim after seeing all the evidence (i.e. doing the research). Rather than finding evidence to fit your idea (cherry-picking), the evidence should help you arrive at the appropriate claim. Cherry-picking evidence can reduce your ethos and weakened your argument.

With these insights in mind, we will introduce you to five evidence types : examples, narratives, facts, statistics, and testimony. Each provides a different type of support, and it’s suggested that you integrate a variety of different evidence types. Understanding the different types of evidence will assist as you work to structure arguments and select support that best fits the goal of your speech.

Examples are specific instances that illuminate a concept. They are designed to give audiences a reference point. An example must be quickly understandable—something the audience can pull out of their memory or experience quickly.

Evidence by example would look like this:

Claim: Textbook affordability initiatives are assisting universities in implementing reputable, affordable textbooks.

Evidence : Ohio has implemented a textbook affordability initiative, the Open Ed Collaborative, to alleviate the financial strain for students (Jaggers, Rivera, Akani, 2019).

Ohio’s affordability initiative functions as evidence by example. This example assists in demonstrating that such initiatives have been successfully implemented. Without providing an example, your audience may be skeptical about the feasibility of your claim.

Examples can be drawn directly from experience, i.e. this is a real example, or an example can be hypothetical where audiences are asked to consider potential scenarios.

Narratives are stories that clarify, dramatize, and emphasize ideas. They have, if done well, strong emotional power (or pathos). While there is no universal type of narrative, a good story often draws the audience in by identifying characters and resolving a plot issue. Narratives can be personal or historical.

Person narratives are powerful tools to relate to your audience and embed a story about your experience with the topic. As evidence, they allow you to say, “I experienced or saw this thing first hand.” As the speaker, using your own experience as evidence can draw the audience in and help them understand why you’re invested in the topic. Of course, personal narratives must be true. Telling an untrue personal narrative may negatively influence your ethos for an audience.

Historical narratives (sometimes called documented narratives) are stories about a past person, place, or thing. They have power because they can prove and clarify an idea by using a common form— the story. By “historical” we do not mean that the story refers to something that happened many years ago, only that it has happened in the past and there were witnesses to validate the happening. Historical narratives are common in informative speeches.

Facts are observations, verified by multiple credible sources, that are true or false. The National Center for Science Education (2008) defines fact as:

an observation that has been repeatedly confirmed an . . . is accepted as ‘true.’ Truth in science, however, is never final and what is accepted as a fact today may be modified or even discarded tomorrow.

“The sun is a star” is an example of a fact. It’s been observed and verified based on current scientific understanding and categorization; however, future technology may update or disprove that fact.

In our modern information age, we recommend “fact-checking a fact” because misinformation can be presented as truth. This means verifying all facts through credible research (check back to Chapter 4 on research). Avoid taking factual information for granted and make sure that the evidence comes from reputable sources that are up-to-date.

S tatistics are the collection, analysis, comparison, and interpretation of numerical data. As evidence, they are useful in summarizing complex information, quantifying, or making comparisons. Statistics are powerful pieces of evidence because numbers appear straightforward. Numbers provide evidence that quantifies, and statistics can be helpful to clarify a concept or highlighting the depth of a problem.

You may be wondering, “What does this actually mean ?” (excuse our statistical humor). We often know a statistic when we find one, but it can be tricky to understand how a statistic was derived.

Averages and percentages are two common deployments of statistical evidence.

An “ a verage ” can be statistically misleading, but it often refers to the mean of a data set. You can determine the mean (or average) by adding up the figures and dividing by the number of figures present. If you’re giving a speech on climate change, you might note that, in 2015, the average summer temperature was 97 degrees while, in 1985, it was just 92 degrees.

When using statistics, comparisons can help translate the statistic for an audience. In the example above, 97 degrees may seem hot, but the audience has nothing to compare that statistic to. The 30-year comparison assists in demonstrating a change in temperature.

A percentag e expresses a proportion of out 100. For example, you might argue that “textbook costs have risen more than 1000% since 1977” (Popken, 2015). By using a statistical percentage, 1000% sounds pretty substantial. It may be important, however, to accompany your percentage with a comparison to assist the audience in understanding that “This is 3 times higher than the normal rate of inflation” (UTA Libraries). You might also clarify that “college textbooks have risen more than any other college-related cost” (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016).

You are responsible for the statistical information that you deploy. It’s all too common for us as information consumers to grab a quick statistic that sounds appealing, but that information may not be reliable.

Be aware of three major statistical issues: small samples, unrepresentative samples, and correlation as causation. In a small sample, an argument is being made from too few examples. In unrepresentative sample, a conclusion is based on surveys of people who do not represent, or resemble, the ones to whom the conclusion is being applied. Finally, it’s common to conflate correlation as causation. In statistics, a correlation refers to the relationship between two variables while causation means that one variable resulted from the other. Be careful not to assume that a correlation means that something has caused the second.

A few other statistical tips:

- Use statistics as support, not as a main point. The audience may cringe or tune you out for saying, “Now I’d like to give you some statistics about the problem of gangs in our part of the state.” That sounds as exciting as reading the telephone book! Use the statistics to support an argument.

- In regard to sources, depend on the reliable ones. Use Chapter 4 as a guide to criticizing and evaluating credible sources.

- Do not overuse statistics. While there is no hard and fast rule on how many to use, there are other good supporting materials and you would not want to depend on statistics alone. You want to choose the statistics and numerical data that will strengthen your argument the most and drive your point home. Statistics can have emotional power as well as probative value if used sparingly.

- Explain your statistics as needed, but do not make your speech a statistics lesson. If you say, “My blog has 500 subscribers” to a group of people who know little about blogs, that might sound impressive, but is it? You can also provide a story of an individual, and then tie the individual into the statistic. After telling a story of the daily struggles of a young mother with multiple sclerosis, you could follow up with “This is just one story in the 400,000 people who suffer from MS in the United States today, according to National MS Society.”

Testimony is the words of others. As evidence, testimony can be valuable to gain insight into an expert or a peer’s opinion, experience, or expertise about a topic. Testimony can provide an audience with a relevant perspective that the speaker isn’t able to provide. We’ll discuss two types of testimony: expert and non-expert.

Expert Testimony

What is an expert? An expert is someone with recognized credentials, knowledge, education, and/or experience in a subject. To quote an expert on expertise, “To be an expert, someone needs to have considerable knowledge on a topic or considerable skill in accomplishing something” (Weinstein, 1993).

A campus bookstore manager could provide necessary testimony on the changing affordability of textbooks over time, for example. As someone working with instructors, students, and publishers, the manager would likely have an insight and a perspective that would be difficult to capture otherwise. They would provide unique and credible evidence.

In using expert testimony, you should follow these guidelines:

- Use the expert’s testimony in their relevant field. A person may have a Nobel Prize in economics, but that does not make them an expert in biology.

- Provide at least some of the expert’s relevant credentials.

- If you interviewed the expert yourself, make that clear in the speech also. “When I spoke with Dr. Mary Thompson, principal of Park Lake High School, on October 12, she informed me that . . .”

Expert testimony is one of your strongest supporting materials to prove your arguments. When integrating their testimony as evidence, make sure their testimony clearly supports your claim (rather than an interesting idea on the topic that is tangential to your assertions).

Non-Expert/Peer Testimony

Any quotation from a friend, family member, or classmate about an incident or topic would be peer testimony. It is useful in helping the audience understand a topic from a personal point of view. For example, you may draw on testimony from a campus student who was unable to afford their campus textbooks. While they may lack formalized expertise in textbook affordability, their testimony might demonstrate how the high cost limited their engagement with the class. Their perspective and insight would be valuable for an audience to hear.

The third component of any argument is the warrant. Warrants connect the evidence and the claim. They often answer the question, “what does this mean?” Warrants are an important component of a complete argument because they:

- Highlight the significance of the evidence;

- Detail how the evidence supports the claims;

- Outline the relevance of the claim and evidence to the audience.

For example, consider the claim that “communication studies provide necessary skills to land you a job.” To support that claim, you might locate a statistic and argue that, “The New York Times had a recent article stating that 80% of jobs want good critical thinking and interpersonal skills.” It’s unclear, however, how a communication studies major would prepare someone to fulfill those needs. To complete the argument, you could include a warrant that explains, “communication studies classes facilitate interpersonal skills and work to embed critical thinking activities throughout the curriculum.” You are connecting the job skills (critical thinking) from the evidence to the discipline (communication studies) from your claim.

Despite their importance, warrants are often excluded from arguments. As speechwriters and researchers, we spend lots of time with our information and evidence, and we take for granted what we know. If you are familiar with communication studies, the connection between the New York Times statistic referenced above and the assertion that communication studies provides necessary job skills may seem obvious. For an unfamiliar audience, the warrant provides more explanation and legitimacy to the evidence.

We know what you’re thinking: “Really? Do I always need an explicit warrant?”

It’s true that some warrants are inferred , meaning that we often recognize the underlying warrant without it being explicitly stated. For example, I might say, “The baking time for my cookies was too hot. The cookies burned.” In this statement, I’m claiming that the temperature is too hot and using burnt cookies as the evidence. We could reasonably infer the warrant, i.e. “burnt cookies are a sign that they were in the oven for too long.”

Inferred warrants are common in everyday arguments and conversations; however, in a formal speech, having a clear warrant will increase the clarity of your argument. If you decide that no explicit warrant is needed, it’s still necessary to ask, “what does this argument mean for my thesis? What does it mean for my audience?” Your goal is to keep as many audience members listening as possible, and warrants allow you to think critically about the information that you’re presenting to that audience.

When writing warrants, keep the following insights in mind:

- Avoid exaggerating your evidence, and make sure your warrant honors what the evidence is capable of supporting;

- Center your thesis statement. Remember that your thesis statement, as your main argument, should be the primary focus when you’re explaining and warranting your evidence.

- A good warrant should be crafted with your content and context in mind. As you work on warrants, ask, “why is this claim/evidence important here? For this argument? Now? For this audience?”

- Say it with us: ethos, pathos, and logos! Warrants can help clarify the goal of your argument. What appeal are you using? Can the warrant amplify that appeal?

Now that you have a better understanding of each component of an argument, let’s conclude this section with a few complete examples.

Claim : The Iowa Wildcats will win the championship. Evidence: In 2019, the National Sporting Association found that the Wildcats had the most consistent and well-rounded coaching staff. Referees of the game agreed, and also praised the players ability for high scoring. Warrant: Good coaching and high scoring are probable indicators of past champions and, given this year’s findings, the Wildcat’s are on mark to win it all.

Here’s an example with a more general approach to track the potential avenues for evidence:

Claim: Sally Smith will win the presidential election. Evidence: [select evidence that highlights their probable win, including: they’ve won the most primaries; they won the Iowa caucus; they’re doing well in swing states; they have raised all the money; they have the most organized campaign.” Warrant: [based on your evidence select, you can warrant why that evidence supports a presidential win].

Using Language Effectively

Claim, evidence, and warrant are useful categories when constructing or identifying a well-reasoned argument. However, a speech is much more than this simple structure over and over (how boring, huh?).

When we craft arguments, it’s tempting to view our audience as logic-seekers who rely solely on rationality, but that’s not true. Instead, Walter Fisher (1984) argues that humans are storytellers, and we make sense of the world through good stories. A good speech integrates argumentative components while telling a compelling story about your argument to the audience. A key piece of that story is how you craft the language—language aids in telling an effective story.

We’ll talk more about language in Chapter 7 (verbal delivery), but there are a few key categories to keep in mind as you construct your argument and story.

Language: What Do We Mean?

Language is any formal system of gestures, signs, sounds, and symbols used or conceived as a means of communicating thought, either through written, enacted, or spoken means. Linguists believe there are far more than 6,900 languages and distinct dialects spoken in the world today (Anderson, 2012). Despite being a formal system, language results in different interpretations and meanings for different audiences.

It is helpful for public speakers to keep this mind, especially regarding denotative and connotative meaning. Wrench, Goding, Johnson, and Attias (2011) use this example to explain the difference:

When we hear or use the word “blue,” we may be referring to a portion of the visual spectrum dominated by energy with a wave-length of roughly 440–490 nanometers. You could also say that the color in question is an equal mixture of both red and green light. While both of these are technically correct ways to interpret the word “blue,” we’re pretty sure that neither of these definitions is how you thought about the word. When hearing the word “blue,” you may have thought of your favorite color, the color of the sky on a spring day, or the color of a really ugly car you saw in the parking lot. When people think about language, there are two different types of meanings that people must be aware of: denotative and connotative. (p. 407)

Denotative meaning is the specific meaning associated with a word. We sometimes refer to denotative meanings as dictionary definitions. The scientific definitions provided above for the word “blue” are examples of definitions that might be found in a dictionary. Connotative meaning is the idea suggested by or associated with a word at a cultural or personal level. In addition to the examples above, the word “blue” can evoke many other ideas:

- State of depression (feeling blue)

- Indication of winning (a blue ribbon)

- Side during the Civil War (blues vs. grays)

- Sudden event (out of the blue)

- States that lean toward the Democratic Party in their voting

- A slang expression for obscenity (blue comedy)

Given these differences, the language you select may have different interpretations and lead to different perspectives. As a speechwriter (and communicator), being aware of different interpretations can allow you select language that is the most effective for your speaking context and audience.

Using Language to Craft Your Argument

Have you ever called someone a “wordsmith?” If so, you’re likely complimenting their masterful application of language. Language is not just something we use; it is part of who we are and how we think. As such, language can assist in clarifying your content and creating an effective message.

Achieve Clarity

Clear language is powerful language. If you are not clear, specific, precise, detailed, and sensory with your language, you won’t have to worry about being emotional or persuasive, because you won’t be understood. The goal of clarity is to reduce abstraction; clarity will allow your audience to more effectively track your argument and insight, especially because they only have one chance to listen.

Concreteness aids clarity. We usually think of concreteness as the opposite of abstraction. Language that evokes many different visual images in the minds of your audience is abstract language. Unfortunately, when abstract language is used, the images evoked might not be the ones you really want to evoke. Instead, work to be concrete, detailed, and specific. “Pity,” for example, is a bit abstract. How might you describe pity by using more concrete words?

Clear descriptions or definitions can aid in concreteness and clarity.

To define means to set limits on something; defining a word is setting limits on what it means, how the audience should think about the word, and/or how you will use it. We know there are denotative and connotative definitions or meanings for words, which we usually think of as objective and subjective responses to words. You only need to define words that would be unfamiliar to the audience or words that you want to use in a specialized way.

Describing is also helpful in clarifying abstraction. The key to description is to think in terms of the five senses: sight (visual: how does the thing look in terms of color, size, shape); hearing (auditory: volume, musical qualities); taste (gustatory: sweet, bitter, salty, sour, gritty, smooth, chewy); smell (olfactory: sweet, rancid, fragrant, aromatic, musky); and feel (tactile: rough, silky, nubby, scratchy).

If you were, for example, talking about your dog, concrete and detailed language could assist in “bring your dog to life,” so to speak, in the moment.

- Boring and abstract: My dog is pretty great. He is well behaved, cute, and is friendly to all of our neighbors. I get a lot of compliments about him, and I really enjoy hanging out with him outside in the summer.

- Concrete and descriptive: Buckley, my golden-brown Sharpei mix, is a one-of-a-kind hound. Through positive treat reinforcement, he learned to sit, shake, and lay down within one month. He will also give kisses with his large and wrinkly snout. He greats passing neighbors with a smile and enjoys Midwest sunbathing on our back deck in the 70-degree heat.

Doesn’t the second description do Image 5.2 more justice ? Being concrete and descriptive paints a picture for the audience and can increase your warrant’s efficacy. Being descriptive, however, doesn’t mean adding more words. In fact, you should aim to “reduce language clutter.” Your descriptions should still be purposeful and important.

Be Effective

Language achieves effectiveness by communicating the right message to the audience. Clarity contributes to effectiveness, but effectiveness also includes using familiar and interesting language.

Familiar language is language that your audience is accustomed to hearing and experiencing. Different communities and audience use language differently. If you are part of an organization, team, or volunteer group, there may be language that is specific and commonly used in those circles. We call that language jargon, or specific, technical language that is used in a given community. If you were speaking to that community, drawing on those references would be appropriate because they would be familiar to that audience. For other audiences, drawing on jargon would be ineffective and either fail to communicate an idea to the audience or implicitly community that you haven’t translated your message well (reducing your ethos).

In addition to using familiar language, draw on language that’s accurate and interesting. This is difficult, we’ll admit it! But in a speech, your words are a key component of keeping the audience motivated to listen, so interesting language can peak and maintain audience interest.

Active language is interesting language. Active voice , when the subject in a sentence performs the action, can assist in having active and engaging word choices. An active sentence would read, “humans caused climate change” as opposed to a passive approach of, “climate change was caused by humans.” Place subjects at the forefront. A helpful resource on active voice can be found here.

You must, however, be reflexive in the language process.

Practicing Reflexivity

Language reflects our beliefs, attitudes, and values – words are the mechanism we use to communicate our ideas or insights. As we learned in Chapter 1, communication both creates and is created by culture. When we select language, we are also representing and creating ideas and cultures – language has a lot of power.

To that end, language should be a means of inclusion and identification, rather than exclusion.

You might be thinking, “Well I am always inclusive in my language,” or “I’d never intentionally use language that’s not inclusive.” We understand, but intention is less important than effect.

Consider the term “millennial”— a categorization that refers to a particular age group. It can be useful to categorize different generations, particularly from a historical and contemporary perspective. However, people often argue that “millennials are the laziest generation” or “millennials don’t know hard work!” In these examples, the intention may be descriptive, but they are selecting language that perpetuates unfair and biased assumptions about millions of people. The language is disempowering (and the evidence, when present, is weak).

Language assists us in categorizing or understanding different cultures, ideas, or people; we rely on language to sort information and differentiate ourselves. In turn, language influences our perceptions, even in unconscious and biased ways.

The key is to practice reflexivity about language choices. Language isn’t perfect, so thinking reflexively about language will take time and practice.

For example, if you were crafting a hypothetical example about an experience in health care, you might open with a hypothetical example: “Imagine sitting for hours in the waiting room with no relief. Fidgeting and in pain, you feel hopeless and forgotten within the system. Finally, you’re greeted by the doctor and he escorts you to a procedure room.” It’s a great story and there is vivid and clear language. But are there any changes that you’d make to the language used?

Remember that this is a hypothetical example. Using reflexive thinking, we might question the use of “he” to describe the doctor. Are there doctors that are a “he”? Certainly. Are all doctors a “he”? Certainly not. It’s important to question how “he” gets generalized to stand-in for doctors or how we may assume that all credible doctors are men.

Practicing reflexivity means questioning the assumptions present in our language choices (like police men rather than police officers). Continue to be conscious of what language you draw on to describe certain people, places, or ideas. If you aren’t sure what language choices are best to describe a group, ask; listen; and don’t assume.

In this chapter, we discussed crafting complete, well-reasoned arguments. Claim, evidence, and warrant are helpful structural components when crafting arguments. Use Chapter 4 to aid in research that will enable you to locate the best evidence for each claim within your speech.

Remember, too, that language plays a central role in telling a compelling story. Up next: organizing and outlining.

Media Attributions

- Sharpei-Mix © Mapes

Speak Out, Call In: Public Speaking as Advocacy Copyright © 2019 by Meggie Mapes is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Asserting is the act of claiming that something is the case—for instance, that oranges are citruses , or that there is a traffic congestion on Brooklyn Bridge (at some time). We make assertions to share information, coordinate our actions, defend arguments, and communicate our beliefs and desires. Because of its central role in communication, assertion has been investigated in several disciplines. Linguists, philosophers of language, and logicians rely heavily on the notion of assertion in theorizing about meaning, truth and inference.

The nature of assertion and its relation to other speech acts and linguistic phenomena (implicatures, presuppositions, etc.) have been subject to much controversy. This entry will situate assertion within speech act theory and pragmatics more generally, and then go on to present the current main accounts of assertion. [ 1 ]

By an account of assertion is here meant a theory of what a speaker does (e.g., expresses a belief ) in making an assertion. According to such accounts, there are deep properties of assertion: specifying those properties is specifying what asserting consists in . There must also be surface properties, which are the properties by which a competent speaker can tell whether an utterance is an assertion, for instance that it is made by means of uttering a sentence in the indicative mood.

We shall classify accounts according two parameters. Firstly, we distinguish between normative and descriptive accounts. Normative accounts rely on the existence of norms or normative relations that are essential to assertoric practice. Descriptive accounts don’t. Secondly, we distinguish between content-directed and hearer-directed accounts. Content-directed accounts focus on the relation between the speaker and the content of the proposition asserted, while hearer-directed accounts focus on the relations between speaker and hearer. Some theories have both normative and descriptive components. The entry is structured as follows

1. Speech Acts

2.1 presupposition, 2.2 implicature, 2.3 indirect assertions, 2.4 explicitness, 3.1 relation to truth, 3.2 cognitive models of communication, 4.1 self-representation, 4.2 communicative intentions, 5.1.1 modern approaches: correctness and warranted assertability, 5.1.2 contemporary approaches: the norm of assertion, 5.1.3 what kind of norm, 5.1.4 which norm of assertion.

- Supplementary Document: Which Kind of Norm?

5.2 Conventions

6.1 commitment, other internet resources, related entries.

Consider typical utterances made by means of the following sentences

Sentence (1a) would typically be used to make an assertion. The speaker would tell or inform a hearer that there is a beer in the fridge. Such an utterance of is called assertoric , or assertive . By contrast, (1b) would be used to ask a question (and the utterance would then be interrogative ), (1c) to express a wish ( optative ), and (1d) to make a command, or a request ( imperative ). This entry is about utterances of the first kind, and about the speech acts performed by means of them.

Gottlob Frege emphasized the distinction between judging a thought content (what Frege called a Thought ) to be true, and merely thinking/entertaining that content. Both are distinct from the content itself. Analogously, he distinguished between utterances with assertoric quality, or force (see below), and utterances without assertoric force. For instance, an assertoric utterance of

as a whole, by which the conditional proposition is asserted, contains as a proper part an utterance or the antecedent ‘it is raining’. But the utterance of “it is raining” is not itself assertoric. The conditional can be true whether the antecedent is true or false, and hence the speaker’s belief about rain is left open by the assertion

Like Frege, C.S. Peirce stressed the importance of distinguishing “between a proposition and what one does with it”. He also adopted, albeit implicitly, a distinction between force and content :

one and the same proposition may be affirmed, denied, judged, doubted, inwardly inquired into, put as a question, wished, asked for, effectively commanded, taught, or merely expressed, and does not thereby become a different proposition (Peirce [NEM]: 248). [ 2 ]

Frege characterized the assertoric quality of an utterance as an assertoric force (“ behauptende Kraft ”; Frege 1918a [TFR: 330]) of the utterance. This idea was later taken over by J. L. Austin (1962 [1975: 99–100]), the founding father of the general theory of speech acts. Austin distinguished between several levels of speech act, including these: the locutionary act, the illocutionary act and the perlocutionary act. The locutionary act is the act of “ ‘saying something’ in the full normal sense” (1962 [1975: 94]), which is the utterance of certain words with certain meanings in a certain grammatical construction, such as uttering ‘I like ice’ as a sentence of English.

The notion of an illocutionary act was introduced by Austin by means of examples (1962 [1975: 98–102]), and that is the normal procedure. Illocutionary acts are such acts as asserting, asking a question, warning, threatening, announcing a verdict or intention, making an appointment, giving an order, expressing a wish, making a request. An utterance of a sentence, i.e., a locutionary act, by means of which a question is asked is thus an utterance with interrogative force , an if an assertion is made, it has assertoric force .

The perlocutionary act is made by means of an illocutionary act, and depends entirely on the hearer’s reaction. For instance, by means of arguing the speaker may convince the hearer, and by means of warning the speaker may frighten the hearer. In these examples, convincing and frightening are perlocutionary acts.

The illocutionary act does not depend on the hearer’s reaction to the utterance. Still, according to Austin (1962 [1975: 116–7]) it does depend on the hearer’s being aware of the utterance and understanding it in a certain way: I haven’t warned someone unless he heard what I said. In this sense, the performance of an illocutionary act depends on the “securing of uptake” (Austin 1962 [1975: 117]). However, although Austin’s view is intuitively plausible for speech acts verbs with speaker-hearer argument structure (like x congratulates y ) or speaker-hearer-content argument structure ( x tells y that p ), it is less plausible when the structure is speaker-content (“Bill asserted that p ”). It may be said that Bill failed to tell Lisa that the station was closed, since she had already left the room when he said so, but that Bill still asserted that it was closed, since Bill believed she was still there. [ 3 ]

Austin had earlier (1956) initiated the development of speech act taxonomy by means of the distinction between constative and performative utterances. Roughly, whereas in a constative utterance you report an already obtaining state of affairs—you say something—in a performative utterance you create something new: you do something (Austin 1956 [1979: 235]). Assertion is the paradigm of a constative utterance. Paradigm examples of performatives are utterances by means of which actions such as baptizing, congratulating and greeting are performed. However, when developing his general theory of speech acts, Austin abandoned the constative/performative distinction, the reason being that it is not so clear in what sense something is done for instance by means of an optative utterance, whereas nothing is done by means of an assertoric one.

Austin noted, e.g., that assertions are subject both to infelicities and to various kinds of appraisal, just like performatives (Austin 1962 [1975: 13–66]). For instance, an assertion is insincere in case of lying as a promise is insincere when the appropriate intention is lacking (Austin 1962 [1975: 40]). This is an infelicity of the abuse kind. Also, an assertion is, according to Austin, void in case of a failed referential presupposition, such as in Russell’s

(Austin 1962 [1975: 20]). This is then an infelicity of the same kind— flaw-type misexecutions —as the use of the wrong formula in a legal procedure (Austin 1962 [1975: 36]), or of the same kind— misinvocations —as when the requirements of a naming procedure aren’t met (Austin 1962 [1975: 51]).

Further, Austin noted that when it comes to appraisals, there is not a sharp difference between acts that are simply true and false, and acts that are assessed in other respects (Austin 1962 [1975: 140–7]). On the one hand, a warning can be objectively proper or improper, depending on the facts. On the other hand, assertions (statements) can be assessed as suitable in some contexts and not in others, and are not simply true or false. [ 4 ]

As an alternative to the constative/performative distinction, Austin suggested five classes of illocutionary types (or illocutionary verbs): verdictives , exercitives , commissives , behabitives and expositives (Austin 1962 [1975: 151–64]). You exemplify a verdictive, e.g., when as a judge you pronounce a verdict; an exercitive by appointing, voting or advising; a commissive by promising, undertaking or declaring that you will do something; a behabitive by apologizing, criticizing, cursing or congratulating; an expositive by acts appropriately prefixed by phrases like ‘I reply’, ‘I argue’, ‘I concede’ etc., of a general expository nature.

In this classification, assertion would best be placed under expositives, since the prefix “I assert” is or may be of an expository nature. Austin explicitly includes the verbs “affirm”, “deny”, and “state”, in his first group of expositives (1962 [1975: 162]). Marina Sbisà (2020) argues that assertion belongs to both expositives and to verdictives, insofar as assertion expresses a judgment/verdict.

Other taxonomies have been proposed, for instance by Stephen Schiffer (1972), John Searle (1975b), Kent Bach and Robert M. Harnish (1979), Francois Recanati (1987), and William P. Alston (2000). [ 5 ]

2. Pragmatics

Assertion is generally thought of being open, explicit and direct, as opposed for instance to implying something without explicitly saying it. In this respect, assertion is contrasted with presupposition and implicature . The contrast is, however, not altogether sharp, partly because of the idea of indirect speech acts, including indirect assertions.

A sentence such as

is not true unless the singular term ‘Kepler’ has reference. Still, Frege argued that a speaker asserting that Kepler died in misery, by means of (4) does not also assert that ‘Kepler’ has reference (Frege 1892 [TPW: 69]). That Kepler has reference is not part of the sense of the sentence. Frege’s reason was that if it had been, the sense of its negation

would have been that Kepler did not die in misery or ‘Kepler’ does not have reference , which is absurd. According to Frege, that ‘Kepler’ has reference is rather presupposed , both in an assertion of (4) and in an assertion of its negation.

The modern treatment of presupposition has followed Frege in treating survival under negation as the most important test for presupposition. That is, if it is implied that p , both in an assertion of a sentence s and in an assertion of the negation of s , then it is presupposed that p in those assertions (unless that p is entailed by all sentences). Other typical examples of presupposition (Levinson 1983: 178–181) include

implying that John tried to stop in time, and

implying that Martha drank John’s home brew.

In the case of (4) , the presupposition is clearly of a semantic nature, since the sentence “Someone is identical with Kepler”, which is true just if ‘Kepler’ has reference, is a logical consequence of (4) and (under a standard interpretation) of (5). By contrast, in the negated forms of (6) and (7) , the presupposition can be canceled by context, e.g., as in

This indicates that in this case the presupposition is rather a pragmatic phenomenon; it is the speaker or speech act rather than the sentence or the proposition expressed that presupposes something.

However, the issue of separating semantic from pragmatic aspects of presupposition is complex, and regarded differently in different approaches to presupposition (for an overview, see Simons 2006). [ 6 ]

Frege noted (1879: [TPW:10]) that there is no difference in truth conditional content between sentences such as

“and” and “but” contribute the same way to truth and falsity. However, when using (9b) , but not when using (9a) , the speaker indicates that there is a contrast of some kind between working with real estate and liking fishing. The speaker is not asserting that there is a contrast. We can test this, for instance, by forming a conditional with (9b) . The antecedent of (10) preserves the contrast rather than make it hypothetical, showing that the contrast is not asserted, forming a conditional with (9b) in the antecedent preserves the contrast rather than make it hypothetical:

It is usually said that the speaker in cases like (9b) and (10) implicates that there is a contrast. These are examples of implicature . H. Paul Grice (1975, 1989) developed a general theory of implicature. Grice called implicatures of the kind exemplified conventional , since it is a standing feature of the word “but” to give rise to them.

Most of Grice’s theory is concerned with the complementing kind, the conversational implicatures. These are subdivided into the particularized ones, which depend on features of the conversational context, and the generalized ones, which don’t (Grice 1975: 37–8). The particularized conversational implicature rely on general conversational maxims, not on features of expressions. These maxims are thought to be in force in ordinary conversation. For instance, the maxim Be orderly ! requires of the speaker to recount events in the order they took place. This is meant to account for the intuitive difference in content between

According to Grice’s account, the speaker doesn’t assert, only implicates that the events took place in the order recounted. What is asserted is just that both events did take place.

Real or apparent violations of the maxims generate implicatures, on the assumption that the participants obey the over-arching Cooperative Principle . For instance, in the conversation

B implicates that he doesn’t know where in Canada John spends the summer. The reasoning is as follows: B violates the Maxim of Quantity to be as informative as required. Since B is assumed to be cooperative, we can infer that he cannot satisfy the Maxim of Quantity without violating some other maxim. The best candidate is the sub-maxim of the Maxim of Quality, which requires you not to say anything for which you lack sufficient evidence. Hence, one can infer that B doesn’t know. Again, B has not asserted that he doesn’t know, but still managed to convey it in an indirect manner. [ 7 ]

The distinction between assertion and implicature is to some extent undermined by acknowledging indirect assertion as a kind of assertion proper. A standard example of an indirect speech act is given by

By means of uttering an interrogative sentence the speaker requests the addressee to pass the salt. The request is indirect. The question, literally concerning the addressee’s ability to pass the salt, is direct. As defined by John Searle (1975b: 59–60), and also by Bach and Harnish (1979: 70), an indirect illocutionary act is subordinate to another, more primary act and depends on the success of the first. An alternative definition, given by Sadock (1974: 73), is that an act is indirect just if it has a different illocutionary force from the one standardly correlated with the sentence-type used.

Examples of indirect assertions by means of questions and commands/requests are given by

(Levinson 1983: 266). Rhetorical questions also have the force of assertions:

Another candidate type is irony:

assuming the speaker does mean the negation of what is literally said. However, although in a sense the act is indirect, since the speaker asserts something different from what she would do on a normal, direct use of the sentence, and relies on the hearer to realize this, it is not an indirect assertion by either definition. It isn’t on the first, since the primary act (the literal assertion) isn’t even made, and it isn’t on the second, since there is no discrepancy between force and sentence type. [ 8 ]

The very idea of indirect speech acts is, however, controversial. It is not universally agreed that an ordinary utterance of (13) is indirect, since it has been denied, e.g., by Levinson (1983: 273–6) that a question has really been asked, over and above the request. Similarly, Levinson have questioned the idea of a standard correlation between force and sentence form, by which a request would count as indirect on Sadock’s criterion.

Common to all conceptions of indirect assertions is that they are not explicit: what is expressed, or literally said, is not the same as what is asserted. One question is whether an utterance is an assertion proper that p if that content is not exactly what is expressed, or whether it is an act of a related kind, perhaps an implicature. [ 9 ]

A related question is how far an utterance may deviate from explicitness and yet be counted as an assertion, proper or indirect. According to one intuition, as soon as it is not fully determinate to the hearer what the intended content of an utterance is, or what force it is made with, the utterance fails to be assertoric. Underdetermination is the crucial issue. This has been argued by Elizabeth Fricker (2012). But the issue is controversial, and objections of several kinds have been made, for instance by John Hawthorne (2012), Andrew Peet (2015, forthcoming) and Manuel García-Carpintero (2016, 2019b). [ 10 ]

3. Descriptive Accounts, Content-Directed

Descriptive accounts characterize assertion in terms of its psychological, social, and linguistic features, without appeal to normative notions. The content-directed accounts focus on the relations between the speaker and content and between hearer and content.

Frege (1918a [TFR: 329]) held that an assertion is an outward sign of a judgment ( Urteil ). A judgment in turn, in Frege’s view, is a step from entertaining a Thought to acknowledging its truth (Frege 1892 [TPW: 64]). [ 11 ] The subject first merely thinks the Thought that p , and then, at the judgment stage, moves on to acknowledge it as true. Since for Frege, the truth value is the reference ( Bedeutung ) of a sentence, a judgment is an advance from the sense of a sentence to its reference. In case the subject makes a mistake, it is not the actual reference, but the reference the subject takes it to have.

For Frege, truth is not relative. There is exactly one point of evaluation of a Thought, the world itself. If instead we accept more than one point of evaluation, such as different possible worlds, truth simpliciter is equated with truth at the actual world. We can then adapt Frege’s view to say that judging that p is advancing to reference at the actual world , or again, evaluating as true in the actual world.

On this picture, what holds for judgment carries over to assertion. It is in the force of an utterance that the step is taken from the content to the actual point of evaluation. This view has been stated by Recanati with respect to the actual world :

[…] a content is not enough; we need to connect that content with the actual world, via the assertive force of the utterance, in virtue of which the content is presented as characterizing that world. (Recanati 2007: 37)

In Pagin (2016a: 276–278), this idea is generalized. If contents are possible-worlds propositions, the points of evaluation are possible worlds. All actual judgments are then applications of propositions to the actual world . If contents are temporal propositions, true or false with respect to world-time pairs, then all actual judgments are applications to the ordered pair of the actual world and a relevant time, usually the time at which the judgment is made. This is the point with respect to which a sentence, used in a context of utterance, has its truth value (cf. Kaplan 1989: 522). Again, the relation is general: if the content of a judgment is a function from indices of some type to truth values, then a judgment is the very step of taking the content to be true at the actual/current index, or again applying the content to that index. The force of an assertion, on this view, connects the content of the assertion with the relevant index. The assertion indicates that the content is true at the index.

On the more social side, it is often said that in asserting a proposition the speaker “presents the proposition as true” (cf. Wright 1992: 34). Prima facie , this characterizes assertion well. However, there are problems with the idea. One is that it should generalize to other speech act types, but does not seem to do so. For instance, does a question present a proposition as one the speaker would like to know the truth value of? If so, it does not seem that this way of presenting the proposition distinguishes between the interrogative force in (17a) , the optative force in (17b) , and the imperative force in (17c) .

If other speech act types could be characterized in ways analogous to assertion, that would strengthen the proposal. If not, it appears to be a weakness.

Another problem is that it remains unclear what “presenting” amounts to. It must be a sense of the word different from that in which the proposition is presented as true in the sentence

even if the sentence is not uttered assertorically. That is, “present as true” must not refer to a feature simply of content . Since there is a sense of “present as such-and-such” that does refer to representational content, there is a need to specify, in a non-question-begging way, the other sense of “present” that is relevant.

In addition, there is a question of distinguishing the assertoric way of presenting something as true from weaker illocutionary alternatives, such as guesses and conjectures, which also in some sense present their contents as being true.

There are therefore weaker senses of “present as true”, which do not require that the presentation itself is made with assertoric force (like an obsolete label on a bottle), and these senses are too weak. There is clearly also a stronger sense that does require assertoric force (for cases when the label is taken to apply), but that is just what we want to have (non-circularly) explained. Simply using the phrase “present as true” does not by itself help.

Another idea for characterizing assertion in terms of truth-related attitudes is that assertion aims at truth. This is stated for instance both by Bernard Williams (1966), by Michael Dummett (1973 [1981]), and more recently by Marsili (2018). The notion of “aiming at truth” can be understood in rather different ways (for some ways of understanding what it could be for belief to aim at truth, see Engel 2004 and Glüer & Wikforss 2013). [ 12 ]

Williams (1966) characterizes assertion’s aim in different terms. For him, the property of aiming at truth is what characterizes fact-stating discourse, as opposed to, e.g., evaluative or directive discourse. It is natural to think of

as stating a fact, and of

as expressing an evaluation, not corresponding to any fact of the matter. On Williams’s view, to regard a sincere utterance of

as a moral assertion , is to take a realistic attitude to moral discourse: there are moral facts, making moral statements objectively true or false. This view again comes in two versions. On the first alternative, the existence of moral facts renders the discourse fact-stating, whether the speaker thinks so or not, and the non-existence renders it evaluative, again whether the speaker thinks so or not. On the second alternative, an utterance of (21) is an assertion if the speaker has a realistic attitude towards moral discourse and otherwise not.

On these views, it is assumed that truth is a substantial property (Williams 1966: 202), not a concept that can be characterized in some deflationary way. As a consequence, the sentence

is to be regarded as false, since (22) is objectively neither true nor false; there is no fact of the matter. [ 13 ]

Perhaps the best way of capturing the cognitive nature of assertion is to give a theory of the cognitive features of normal communication by means of assertion. A classic theory is Stalnaker’s (1974, 1978). Stalnaker provides a model of a conversation in which assertion and presupposition dynamically interact. On Stalnaker’s model, propositions are presupposed in a conversation if they are on record as belonging to the common ground between the speakers. When an assertion is made and accepted in the conversation, its content is added to the common ground, and the truth of the proposition in question will be presupposed in later stages. What is presupposed at a given stage has an effect on the interpretation of new utterances made at that stage. For Stalnaker, the common ground is a set of propositions. He models this with the set of worlds in which all common ground propositions are true, the context set .

In this framework Stalnaker (1978: 88–89) proposes three rules for assertion:

Stalnaker comments on the first rule:

To assert something incompatible with what is presupposed is self-defeating […] And to assert something which already presupposed is to attempt to do something that is already done.

On such an approach, the satisfaction of a presupposition is an admittance condition of an assertion (cf. Karttunen 1974; Heim 1988). This idea connects with Austin’s more general idea of felicity conditions of speech acts. [ 14 ] Does Stalnaker offer an account of assertion itself? The answer is no, for the role of assertion is shared by other speech acts such as assuming and conjecturing (Stalnaker 1978: 153). What is added to the common ground is only for the purpose of conversation, and need not be actually believed by the participants. It is only required that it be accepted (cf. Stalnaker 2002: 716).

Stalnaker has not (as far as we are aware) attempted to add a distinguishing feature of assertion to the model. This has, however, been attempted by Schaffer (2008), Kölbel (2011: 68–70), and Stokke (2013). [ 15 ]

Another cognitive account is offered by Pagin (2011, 2020). The account is summarized by the phrase: “an assertion is an utterance that is prima facie informative”. For an utterance to be informative is for it to be made in part “because it is true”. What this amounts to is different, but complementary, for speaker and hearer. For the speaker, part of the reason for using a particular sentence is that it is true (in context); that is, the speaker believes, with a sufficient strength, that the sentence expresses a true proposition, and utters it partly because of that. For the hearer, taking the utterance as informative, means, by default, to update their credence in the proposition as a response to the utterance, both in the upwards direction and to a level above 0.5.

The prima facie element of the account means that the typical properties on the speaker and hearer side are only default properties associated with surface features of the utterance: the declarative sentence type, a typical intonation pattern, etc. There are many possible reasons why a speaker may utter such a sentence without believing the proposition, and why a hearer may not adjust their credence in the typical manner. For example, the speaker may be lying, the hearer may distrust the speaker, or may already have given the proposition a very high credence before the utterance. On Pagin’s picture, it is the cognitive patterns associated with surface features, on the production and comprehension sides, that characterize assertion. This way of dividing the account between speaker and hearer is somewhat controversial.

Yet another cognitive account is elaborated in Jary (2010). Jary’s account is situated within Relevance Theory , a more general account of cognition and communication. As a typical ingredient of this general framework, when an assertion is made, the proposition expressed by the utterance is presented as “relevant to the hearer” (2010: 163), where ‘relevant’ is a technical term (Sperber & Wilson 1986 [1995: 265]).

What distinguishes assertion from other speech act types is something different:

Assertion cannot be defined thus, though. In order for an utterance to have assertoric force, it must also be subject to the cognitive and social safeguards that distinguish assertion. […] It is the applicability of these safeguards that distinguishes assertion both from other illocutionary acts and from other forms of information transfer. (Jary 2010: 163–164)

Social safeguards consist in sanctions against misleading assertions, while cognitive safeguards consist in the ability of the hearer to not simply accept what is said but meta-represent the speaker as expressing certain beliefs and intentions (2010: 160). It is part of a full account of assertion, according to Jary, that assertions are subject to these safeguards. This also distinguishes assertions from promises and commands, where the proposition is not presented as subject to the hearer’s safeguards; “rejection is not presented as an option for the hearer” (2010: 73).

4. Descriptive Accounts, Hearer-Directed

Hearer-directed accounts of assertion are primarily concerned with the speaker’s thoughts and intentions about their audience.

According to Frege (1918a [TFR: 329]), as noted, an assertion is an outward sign of a judgment ( Urteil ). The term “judgment” has been used in several ways. If it is used to mean either belief , or act by which a belief is formed or reinforced , then Frege’s view is pretty close to the view that assertion is the expression of belief .

This idea, that assertion is the expression of belief, has a longer history, going back to at least Kant. How should one understand the idea of expressing here? It is natural to think of a belief state, that is, a mental state of the speaker, as causally co-responsible for the making of the assertion. The speaker has a belief and wants to communicate it, which motivates an assertoric utterance. But what about the cases when the speaker does not believe what he asserts? Can we still say, even of insincere assertions, that they express belief? If so, in what sense?

Within the communicative intentions tradition, Bach and Harnish have emphasized that an assertion gives the hearer evidence for the corresponding belief, and that what is common to the sincere and insincere case is the intention of providing such evidence:

For S to express an attitude is for S to R -intend the hearer to take S ’s utterance as reason to think S has that attitude. (Bach & Harnish 1979: 15, italics in the original)

(‘R-intend’ is, as above, short for “reflexively intend”). On this view, expressing is wholly a matter of hearer-directed intentions.

This proposal has the advantage of covering both the sincere and the insincere case, but has the drawback of requiring a high level of sophistication. By contrast, Bernard Williams (2002: 74) has claimed that a sincere assertion is simply the direct expression of belief, in a more primitive and unsophisticated way. Insincere assertions are different. According to Williams (2002: 74), in an assertion, the speaker either gives a direct expression of belief, or he intends the addressee to “take it” that he has the belief (cf. Owens 2006).

Presumably, the intention mentioned is an intention about what the hearer is to believe about the speaker. In this case the objection that too much sophistication is required is less pressing, since it only concerns insincere assertions. However, Williams’s idea (as in Grice 1969) has the opposite defect of not taking more sophistication into account. The idea, that the alternative to sincerity is the intention to make the hearer believe that the speaker believes what he asserts, is not general enough. For instance, there is double bluffing, where the speaker asserts what is true in order to deceive the hearer, whom the speaker believes will expect the speaker to lie. Again, an insincere speaker S who asserts that p may know that the hearer A knows that S does not believe that p , but may still intend to make A believe that S does not know about A ’s knowledge, precisely by making the assertion that p . There is no definitive upper limit to the sophistication of the deceiving speaker’s calculations. In addition, the speaker may simply be stonewalling, reiterating an assertion without any hope of convincing the addressee of anything.

A more neutral way of trying to capture the relation between assertion and believing was suggested both by Max Black (1952) and by Davidson (1984: 268): in asserting that p the speaker represents herself as believing that p . This suggestion appears to avoid the difficulties with the appeal to hearer-directed intentions.

A somewhat related approach is taken by Mitchell S. Green (2007), who appeals to “expressive conventions”. Grammatical moods can have such conventions (2007: 150). According to Green (2007: 160), an assertion that p invokes a set of conventions according to which the speaker “can be represented as bearing the belief-relation to p ”.

As one can represent oneself as believing, one can also represent oneself as knowing. Inspired by Davidson’s proposal, Peter Unger (1975: 253–270) and Michael Slote (1979: 185) made the stronger claim that in asserting that p the speaker represents herself as knowing that p . To a small extent this idea had been anticipated by G. E. Moore when claiming that the speaker implies that she knows that p (1912 [1966: 63]).

However, it is not so clear what representing oneself amounts to. It must be a sense different from that in which one represents the world as having certain features. The speaker who asserts

does not also claim that she believes that there are black swans. It must apparently be some weaker sense of “represent”, since it is not just a matter of being, as opposed to not being, fully explicit. If I am asked what I believe and I answer by uttering (23) , I do represent myself as believing that there are black swans, just as I would have done by explicitly saying that I believe that there are black swans. I do represent myself as believing that there are black swans, equivalently with asserting that I do. What I assert then is false if I don’t have the belief, despite the existence of black swans.

On the other hand, it must also be stronger than the sense of “represent” by which an actor can be said to represent himself as believing something on stage. The actor says

thereby representing himself as asserting that he is in the biology department, since he represents himself as being a man who honestly asserts that he is in the biology department. By means of that, he in one sense represents himself as believing that he is in the biology department. But the audience not invited to believe that the speaker, that is, the actor, has that belief.

Apparently, the relevant sense of “represent” is not easy to specify. That it nevertheless tracks a real phenomenon is often claimed to be shown by Moore’s Paradox. This is the paradox that assertoric utterances of sentences such as

(the omissive type of Moorean sentences) are distinctly odd, and even prima facie self-defeating, despite the fact that they may well be true. Among the different types of account of Moore’s Paradox, Moore’s own emphasizes the connection between asserting and believing. Moore’s idea (1944: 175–176; 1912 [1966: 63]) was that the speaker in some sense implies that she believes what she asserts. So by asserting (25) the speaker induces a contradiction between what she asserts and what she implies. This contradiction is then supposed to explain the oddity. [ 16 ]

Typically, the speaker who makes an assertion has hearer-directed intentions in performing a speech act. The speaker may intend the hearer to come to believe something or other about the speaker, or about something else, or intend the hearer to come to desire or intend to do something. Such intentions can concern institutional changes, but need not. Intentions that are immediately concerned with communication itself, as opposed to ulterior goals, are called communicative intentions .

The idea of communicative intentions derives from Grice’s (1957) article ‘Meaning’, where Grice defined what it is for a speaker to non-naturally mean something. Although Grice did not explicitly attempt to define assertion, his ideas can be straightforwardly transposed to provide a definition:

In the early to mid 1960s Austin’s speech act theory and Grice’s account of communicative intentions began to merge. The connection is discussed in Strawson 1964. Strawson inquired whether illocutionary force could be made overt by means of communicative intentions. He concluded that when it comes to highly conventionalized utterances, communicative intentions are largely irrelevant, but that on the other hand, convention does not play much role for ordinary illocutionary types. Strawson also pointed out a difficulty with Grice’s analysis: it may be the case that all three conditions (i-iii) are fulfilled, but that the speaker intends the hearer to believe that they aren’t (for instance, if the speaker wants the hearer to believe that p for reasons altogether independent from his making the statement).

Such intentions to mislead came to be called sneaky intentions (Grice 1969), and they constituted a problem for speech act analyses based on communicative intentions. The idea was that genuine communication is essentially open: the speaker’s communicative intentions are meant to be fully accessible to the hearer. Sneaky intentions violate this requirement of openness, and therefore apparently they must be ruled out one way or another. Strawson’s own solution was to add a fourth clause about the speaker’s intention that the hearer recognize the third intention. However, that solution only invited a sneaky intention one level up (cf. Schiffer 1972: 17–42; Vlach 1981; Davis 1999).

Another solution was to make the intention reflexive . This was proposed by Searle (1969), in the first full-blown analysis of illocutionary types made by appeal to communicative intentions. Searle combined this with an appeal to social institutions as created by rules. We return to these in section 5.1 .

Searle criticized Grice for requiring the speaker to intend perlocutionary effects, such as what the speaker shall come to do or believe, pointing out that such intentions aren’t essential (1969: 46–7). Instead, according to Searle, the speaker intends to be understood , and also intends to achieve this by means of the hearer’s recognition of this very intention itself. Moreover, if the intention is recognized, it is also fulfilled: “we achieve what we try to do by getting our audience to recognize what we try to do” (Searle 1969: 47). This reflexive intention is formally spelled out as follows:

The illocutionary effect IE is the effect of generating the state specified in the constitutive rule. In the case of assertion, the speaker intends that her utterance counts as an undertaking that p represents an actual state of affairs, depending on the constitutive rule (cf. section 5.1 ).

Bach and Harnish follow Searle in appealing to reflexive communicative intentions. On their analysis (1979: 42), assuming a speaker S and a hearer H ,

According to Bach and Harnish’s understanding, a speaker S expresses an attitude just in case S R -intends (reflexively intends) the hearer to take S ’s utterance as reason to think S has that attitude. They understand the reflexive nature of the intention pretty much like Searle. They say (1979: 15) that the intended effect of an act of communication is not just any effect produced by means of recognition of the intention to produce a certain effect, it is the recognition of that intention .

These appeals to reflexive intentions were later criticized, in particular by Sperber and Wilson (1986 [1995:256–257]). Their point is that if an intention I has as sub-intentions both the intention J and the intention that the hearer recognize I , this will yield an infinitely long sequence: the intention that: J and the hearer recognize the intention that: J and the hearer recognize the intention that: J and …). If this is an intention content at all, it is not humanly graspable. [ 17 ]

Apart from the communicative intentions accounts of assertion, there are more general questions about what intentions are required of a speaker in order for his utterance to qualify as an assertion. For instance, must he intend it to be an assertion? Must it be made voluntarily?

5. Normative Accounts, Content-Directed

5.1 norms of assertion.

Most of the discussion on assertion during the past twenty years has concerned norms of assertability. Simply put, philosophers aim to determine under which conditions it is epistemically permissible (or proper, warranted, correct, appropriate) to make an assertion.

Philosophers have long been interested in analyzing what we mean when we characterize an assertion as “correct”, “justified”, “proper”, “warranted”, “assertible”, or “warrantedly assertible”. The latter notion was taken on board in pragmatism, and in later forms of anti-realism. Dewey (1938) seems to have been the first to characterize truth in terms of assertoric correctness, with his notion of warranted assertibility , even though this idea had a clear affinity with the verifiability principle of Moritz Schlick (1936). Dewey, following Peirce, regarded truth as the ideal limit of scientific inquiry (1938: 345), and a proposition warrantedly asserted only when known in virtue of such an inquiry. Warranted assertibility is the property of a proposition for which such knowledge potentially exists (1938: 9). Dewey was later followed by, notably, Dummett (1976) and Putnam (1981). Common to them is the position that there cannot be anything more to truth than being supported by the best available evidence. In these early discussions, the strategy was that of getting a handle on truth by means of an appeal to the notion of the correctness of an assertion, which was taken as more fundamental. On Dummett’s view, we do get a notion of truth distinct from the notion of a correct assertion only because of the semantics of compound sentences (1976: 50–52). The question of what the correctness of an assertion consists in was not itself much discussed in earlier work, but became subject of discussion already in the 1980s, with the work of Boghossian and others.