- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Linguistic Profiling and Language-Based Discrimination

Introduction, general overviews.

- Foundations and Extensions

- Phonetic and Acoustical Analyses

- Linguistic Discrimination in the Workplace

- Evidence of Linguistic Bias in Housing Markets

- Educational Studies: Bilingual and Bidialectal Considerations

- Language and Gender: Evidence of Bias in Linguistic Style and Conversation

- Language Usage among Racial and Ethnic Minorities

- Linguistic Prejudice and the Law

- Linguistic Human Rights

- Alternative Perspectives

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Bilingualism and Multilingualism

- Contrastive Analysis in Linguistics

- Conversation Analysis

- Critical Applied Linguistics

- Cross-Cultural Pragmatics

- Cross-Language Speech Perception and Production

- Dialectology

- Educational Linguistics

- English as a Lingua Franca

- Euphemisms and Dysphemisms

- Heritage Languages

- Institutional Pragmatics

- Language and Law

- Language Contact

- Language, Gender, and Sexuality

- Language Ideologies and Language Attitudes

- Language Maintenance

- Language Revitalization

- Linguistic Complexity

- Linguistic Prescriptivism

- Minority Languages

- Positive Discourse Analysis

- Sociolinguistic Fieldwork

- Sociopragmatics

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Attention and Salience

- Edward Sapir

- Text Comprehension

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Linguistic Profiling and Language-Based Discrimination by John Baugh LAST REVIEWED: 12 January 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 12 January 2021 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199772810-0267

Linguistic profiling and other forms of linguistic discrimination were first attested in the Old Testament. The coinage of the word shibboleth traces its origin to the Book of Judges 12:6, where the inability to pronounce that word correctly would result in death; “They told him, ‘Please say shibboleth.’ If he said, ‘sibboleth,’ because he could not pronounce it correctly, they seized him and killed him at the fords of the Jordan.” Since then, other manifestations of human conflict and discrimination frequently exhibit linguistic demarcation in one form or another, and these shibboleths evolve over time. Warring factions may eventually make peace, as old rivalries come to be displaced or resolved. Advances in technology exacerbated these trends, as more-rapid modes of transportation increased contact and conflict among speakers of mutually unintelligible languages, accompanied by the development of increasingly efficient deadly weaponry that coincided with global expansionism along with sporadic conquests and the ensuing oppression of human enclaves throughout the world. The advent of global markets and multinational immigration has further accelerated circumstances where diverse human factions may use linguistic (dis)similarities as one of several means through which individuals formulate perceptual boundaries between groups that are familiar or unfamiliar. When compared to the historical longevity of discrimination based on language, linguistic evaluations of this phenomenon are relatively recent.

Haugen 1972 is among the first works by many professional linguists to call attention to the stigmatization of bilingualism as experienced by various immigrant groups in the United States. Lambert 1972 and Tucker and Lambert 1969 are experimental studies that expose further evidence of linguistic bias in bilingual (e.g., French and English in Canada) and bidialectal circumstances (e.g., mainstream Standard American English and African American vernacular English in the United States). Preston 1989 is a formulation of perceptual dialectology that provides orthogonal confirmation of such biases, through elicitations of opinions about superior-to-inferior varieties of American English. Explicit accounts of linguistic profiling are described in Purnell, et al. 1999 regarding housing discrimination and in Baugh 2000 in relation to testimony about different speakers’ dialects and racial identities during murder trials. Squires and Chadwick 2006 produces complementary analyses by uncovering differential dialect discrimination against minorities seeking to purchase homeowners’ insurance. In Zentella 2014 , evaluations of linguistic profiling share echoes of Einar Haugen’s early observations about prejudice against bilinguals, albeit with specific relevance to native speakers of Spanish who were obliged to speak English exclusively at their places of employment. Jones, et al. 2019 discovers unintended bias against black Americans by professional court reporters who regularly mischaracterized their statements during trials. When viewed collectively, matters of linguistic profiling and language discrimination persist in many social domains, thereby confirming the existence of one demographic dimension of human inequality.

Baugh, John. 2000. Racial identification by speech. American Speech 75.4: 362–364.

DOI: 10.1215/00031283-75-4-362

A survey of legal cases devoted to murder trials where the dialect of suspects or defendants was central to witness testimony. The phrase “linguistic profiling” first appeared in this article, and that concept has since expanded to include prejudicial, and often illegal, reactions to the speech or writing of individuals whose language usage was used as the basis of discrimination against them.

Haugen, Einar. 1972. The ecology of language . Stanford, CA: Stanford Univ. Press.

A collection of interdisciplinary chapters that describe the intersection between linguistic diversity and America’s expanding global immigrant population. “The Stigmata of Bilingualism” is most relevant to linguistic discrimination, and it stands out among an array of other chapters dealing with a wide range of bilingual considerations that address linguistic prejudice against those who are not native speakers of English, with special relevance to the United States.

Jones, Taylor, Jessica Rose Kalbfeld, Ryan Hancock, and Robin Clark. 2019. Testifying while black: An experimental study of court reporter accuracy in transcription of African American English. Language 95.2: 216–252.

DOI: 10.1353/lan.2019.0042

Court stenographers in Philadelphia repeatedly produced inaccurate transcriptions of African American English (AAE), including different morphosyntactic and phonological features of AAE. These errors were consequential, changing official court records that would have significant legal repercussions for typical speakers of AAE.

Lambert, Wallace. 1972. Language, psychology and culture: Essays . Selected and introduced by Anwar S. Dil. Stanford, CA: Stanford Univ. Press.

Foundational research on societal and personal dimensions of bilingualism and biculturalism, including results from carefully controlled matched-guise experiments that revealed differential attitudes toward French and English in Canada. These attitudinal differences were measured with Likert scales that considered friendliness, trustworthiness, and educational status, among other traits.

Preston, Dennis. 1989. Perceptual dialectology: Nonlinguists’ views of areal linguistics . Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Foris.

Opinions about language usage were solicited in Indiana and Hawaii regarding perceptions about dialect differences, with primary emphasis on preferred manners of speaking in contrast to speech that was deemed less desirable, or incorrect. The field of perceptual dialectology is introduced and formulated in this volume.

Purnell, Thomas, William Idsardi, and John Baugh. 1999. Perceptual and phonetic experiments on American English dialect identification. Journal of Language and Social Psychology 18.1: 10–30.

DOI: 10.1177/0261927X99018001002

Controlled experiments were conducted that showed bias against vernacular African American and vernacular Mexican American varieties of English in contrast to the dominant Standard American English dialect, which was preferred by landlords. Accurate identification of the race of speakers was determined with high rates of accuracy upon hearing the single word “hello.”

Squires, Greg, and Jan Chadwick. 2006. Linguistic profiling: A continuing tradition of discrimination in the home insurance industry? Urban Affairs Review 41.3: 400–415.

DOI: 10.1177/1078087405281064

An audit-pair study that exposed linguistic and racial bias against minority speakers who were seeking to purchase homeowners’ insurance. These findings confirm that some insurance agents would deduce the race of prospective clients during telephone calls. In many instances, these agents then denied minority prospects from purchasing homeowners’ insurance that would otherwise be available.

Tucker, Richard, and Wallace Lambert. 1969. White and Negro listeners’ reactions to various American-English dialects. Social Forces 47.4: 463–468.

DOI: 10.2307/2574535

An experimental study of diverse AAE speech styles that includes well-educated and less well-educated black speakers who were evaluated by diverse white and black (i.e., Negro) listeners. Each listener evaluated individual speech samples with a Likert scale that included various demographic categories such as education, wealth, and friendliness.

Zentella, Ana Celia. 2014. TWB (talking while bilingual): Linguistic profiling of Latina/os and other linguistic torquemadas . Latino Studies 12.4: 620–635.

DOI: 10.1057/lst.2014.63

Bilingual New Yorkers who were native speakers of Spanish were forced to speak English at their workplace under all circumstances, including personal conversations that were unrelated to their job. A survey was conducted, revealing differences of opinion about the importance and appropriateness of demanding exclusive usage of English.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Linguistics »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Acceptability Judgments

- Accessibility Theory in Linguistics

- Acquisition, Second Language, and Bilingualism, Psycholin...

- Adpositions

- African Linguistics

- Afroasiatic Languages

- Algonquian Linguistics

- Altaic Languages

- Ambiguity, Lexical

- Analogy in Language and Linguistics

- Animal Communication

- Applicatives

- Applied Linguistics, Critical

- Arawak Languages

- Argument Structure

- Artificial Languages

- Australian Languages

- Austronesian Linguistics

- Auxiliaries

- Balkans, The Languages of the

- Baudouin de Courtenay, Jan

- Berber Languages and Linguistics

- Biology of Language

- Borrowing, Structural

- Caddoan Languages

- Caucasian Languages

- Celtic Languages

- Celtic Mutations

- Chomsky, Noam

- Chumashan Languages

- Classifiers

- Clauses, Relative

- Clinical Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Colonial Place Names

- Comparative Reconstruction in Linguistics

- Comparative-Historical Linguistics

- Complementation

- Complexity, Linguistic

- Compositionality

- Compounding

- Comprehension, Sentence

- Computational Linguistics

- Conditionals

- Conjunctions

- Connectionism

- Consonant Epenthesis

- Constructions, Verb-Particle

- Conversation, Maxims of

- Conversational Implicature

- Cooperative Principle

- Coordination

- Creoles, Grammatical Categories in

- Critical Periods

- Cyberpragmatics

- Default Semantics

- Definiteness

- Dementia and Language

- Dene (Athabaskan) Languages

- Dené-Yeniseian Hypothesis, The

- Dependencies

- Dependencies, Long Distance

- Derivational Morphology

- Determiners

- Distinctive Features

- Dravidian Languages

- Endangered Languages

- English, Early Modern

- English, Old

- Eskimo-Aleut

- Evidentials

- Exemplar-Based Models in Linguistics

- Existential

- Existential Wh-Constructions

- Experimental Linguistics

- Fieldwork, Sociolinguistic

- Finite State Languages

- First Language Attrition

- Formulaic Language

- Francoprovençal

- French Grammars

- Gabelentz, Georg von der

- Genealogical Classification

- Generative Syntax

- Genetics and Language

- Grammar, Categorial

- Grammar, Cognitive

- Grammar, Construction

- Grammar, Descriptive

- Grammar, Functional Discourse

- Grammars, Phrase Structure

- Grammaticalization

- Harris, Zellig

- History of Linguistics

- History of the English Language

- Hmong-Mien Languages

- Hokan Languages

- Humor in Language

- Hungarian Vowel Harmony

- Idiom and Phraseology

- Imperatives

- Indefiniteness

- Indo-European Etymology

- Inflected Infinitives

- Information Structure

- Interface Between Phonology and Phonetics

- Interjections

- Iroquoian Languages

- Isolates, Language

- Jakobson, Roman

- Japanese Word Accent

- Jones, Daniel

- Juncture and Boundary

- Khoisan Languages

- Kiowa-Tanoan Languages

- Kra-Dai Languages

- Labov, William

- Language Acquisition

- Language Documentation

- Language, Embodiment and

- Language for Specific Purposes/Specialized Communication

- Language Geography

- Language in Autism Spectrum Disorders

- Language Nests

- Language Shift

- Language Standardization

- Language, Synesthesia and

- Languages of Africa

- Languages of the Americas, Indigenous

- Languages of the World

- Learnability

- Lexical Access, Cognitive Mechanisms for

- Lexical Semantics

- Lexical-Functional Grammar

- Lexicography

- Lexicography, Bilingual

- Linguistic Accommodation

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Areas

- Linguistic Landscapes

- Linguistic Profiling and Language-Based Discrimination

- Linguistic Relativity

- Linguistics, Educational

- Listening, Second Language

- Literature and Linguistics

- Machine Translation

- Maintenance, Language

- Mande Languages

- Mass-Count Distinction

- Mathematical Linguistics

- Mayan Languages

- Mental Health Disorders, Language in

- Mental Lexicon, The

- Mesoamerican Languages

- Mixed Languages

- Mixe-Zoquean Languages

- Modification

- Mon-Khmer Languages

- Morphological Change

- Morphology, Blending in

- Morphology, Subtractive

- Munda Languages

- Muskogean Languages

- Nasals and Nasalization

- Niger-Congo Languages

- Non-Pama-Nyungan Languages

- Northeast Caucasian Languages

- Oceanic Languages

- Papuan Languages

- Penutian Languages

- Philosophy of Language

- Phonetics, Acoustic

- Phonetics, Articulatory

- Phonological Research, Psycholinguistic Methodology in

- Phonology, Computational

- Phonology, Early Child

- Policy and Planning, Language

- Politeness in Language

- Possessives, Acquisition of

- Pragmatics, Acquisition of

- Pragmatics, Cognitive

- Pragmatics, Computational

- Pragmatics, Cross-Cultural

- Pragmatics, Developmental

- Pragmatics, Experimental

- Pragmatics, Game Theory in

- Pragmatics, Historical

- Pragmatics, Institutional

- Pragmatics, Second Language

- Pragmatics, Teaching

- Prague Linguistic Circle, The

- Presupposition

- Psycholinguistics

- Quechuan and Aymaran Languages

- Reading, Second-Language

- Reciprocals

- Reduplication

- Reflexives and Reflexivity

- Register and Register Variation

- Relevance Theory

- Representation and Processing of Multi-Word Expressions in...

- Salish Languages

- Sapir, Edward

- Saussure, Ferdinand de

- Second Language Acquisition, Anaphora Resolution in

- Semantic Maps

- Semantic Roles

- Semantic-Pragmatic Change

- Semantics, Cognitive

- Sentence Processing in Monolingual and Bilingual Speakers

- Sign Language Linguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Sociolinguistics, Variationist

- Sound Change

- South American Indian Languages

- Specific Language Impairment

- Speech, Deceptive

- Speech Perception

- Speech Production

- Speech Synthesis

- Switch-Reference

- Syntactic Change

- Syntactic Knowledge, Children’s Acquisition of

- Tense, Aspect, and Mood

- Text Mining

- Tone Sandhi

- Transcription

- Transitivity and Voice

- Translanguaging

- Translation

- Trubetzkoy, Nikolai

- Tucanoan Languages

- Tupian Languages

- Usage-Based Linguistics

- Uto-Aztecan Languages

- Valency Theory

- Verbs, Serial

- Vocabulary, Second Language

- Voice and Voice Quality

- Vowel Harmony

- Whitney, William Dwight

- Word Classes

- Word Formation in Japanese

- Word Recognition, Spoken

- Word Recognition, Visual

- Word Stress

- Writing, Second Language

- Writing Systems

- Zapotecan Languages

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [185.80.149.115]

- 185.80.149.115

- Across the sea of dreams: Alvvays + The Beths at The Sound

- To the stars with Olivia Rodrigo: GUTS world tour

- Comment from Professor Allan Havis: A Message supporting Shared Discourse

- Voices from Inside the Encampment

- A review of UCSD classrooms

- Court orders for UAW strike to pause

- The Social Security tax is almost certainly rigged against you

- Reports of arrested students receive holds on their accounts, some concerned about Graduation

- Statement from the UC San Diego writing community: “You wrote them in the cruelest way”

- Letter from UC San Diego Faculty to the Students of the Gaza Solidarity Encampment

The UCSD Guardian

Linguistic Profiling Rooted in Implicit Bias, Stereotyping

There is a decent pool of Americans who will insist they do not have an accent. Of course, there are accents that are found within Southern regions of America or on the East Coast, but still, some Americans may describe their way of speaking to not have a specific “flair” — it’s just “normal.” “Accentless” Americans do, contrary to their belief, have an accent. The reason they might have never realized it is because it does not inconvenience them.

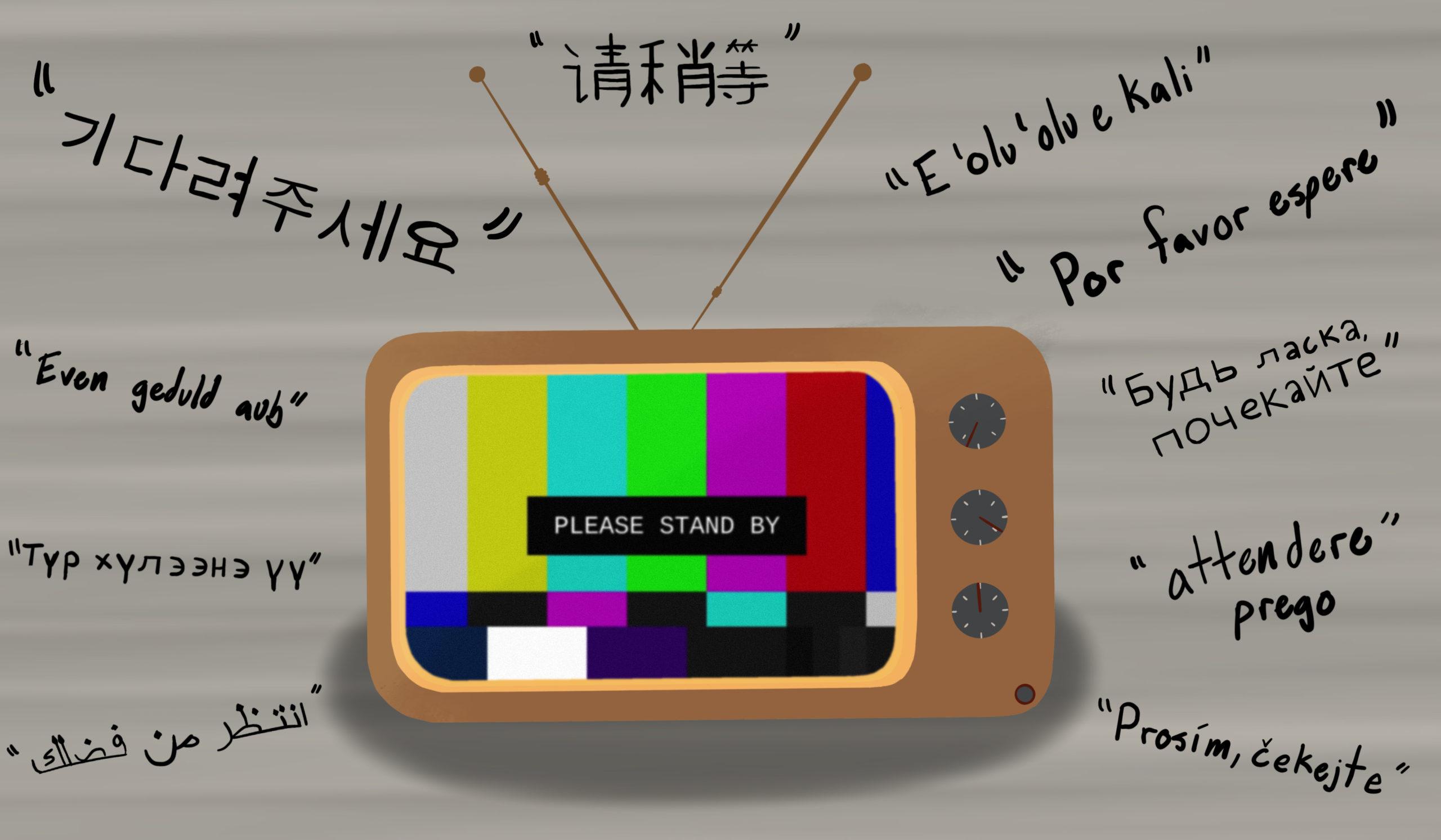

The denial of otherwise available goods or services by phone is what has been coined “linguistic profiling,” and it is the auditory correspondent to racial profiling, which relies on visual cues. Over the phone, employers or landlords, for sake of example, can utilize accents of potential job applicants or tenants to decide whether or not they want to turn them away.

It is not linguistic profiling for someone to acknowledge a caller sounds Latino, Black, Indian, or any other racial or ethnic background. It becomes linguistic profiling once someone attaches their implicit biases to the fact that callers sound as if they are part of a certain group or community and decides to discriminate against them. It is an easy way for people to quickly make assumptions about a caller and decide if they are part of a community they have a prejudice against. While turning away a caller on the phone may sound mundane, linguistic profiling is another way for those with implicit biases against people of color to potentially put minorities in disadvantaged situations. What is exceptionally upsetting, is that people will linguistically profile communities for the way they sound, but will still actively use ways of speech (such as terms or vernacular) used by POC once it is trending.

Within America, t he Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Fair Housing Act of 1968 both account for linguistic profiling and the Civil Rights Act has avowed discrimination based on “linguistic characteristics of a national origin group” are forbidden. While these laws were a step in the right direction, linguistic profiling has proven difficult to fight within the court of law; especially as it can be challenging to document speech was the basis for discrimination. Does that mean it is not happening? No. It means someone can discriminate against someone else on the basis of an accent they hold as distasteful and potentially get off with no consequence. Lack of consequence allows for people to not be held accountable for when they do discriminate on the basis of linguistic profiling. That means not only are victims left without justice, but perpetrators are left without seeing reason to change their mentality nor behavior.

Lack of consequence can also perpetuate the notion that linguistic profiling does affect anyone. Studies that have focused on linguistic profiling have been able to find a correlation between accents used and whether or not individuals get a call back. The correlation does not give the full picture, but it does encourage further research and investigation.

Current data on linguistic profiling remains conservative, as not many cases can be represented and few may admit to actively doing it. But in reality, linguistic profiling does happen, and all while someone can disadvantage POC for the way they speak, they can be using popularized POC terms. African-American Vernacular English (AAVE), Mexican Slang, Japanese words, and plenty of other culture’s speech have been highlighted by trends, allowing for anyone to suddenly be taking pieces of that culture’s vernacular and incorporate it into their own verbal communication. “Accentless” Americans have found themselves within a group who enjoys playing with words and phrases like “woke,” “por favor,” or even ”sugoi.” It might make you feel quirky and it might feel harmless. In reality, it is tone deaf. POC, as humans, can be turned away, but their culture and way of speaking can be accepted because it’s “fun.”

Using POC terms while linguistically profiling them only supports the notion that minorities are accepted in capacities that are convenient for others. The issue is not entirely about accents or the way someone speaks, it’s about trying to distance yourself from who has the accent.

To reduce someone down to an unappealing voice and then turn around and try to speak in manners specific to their culture is a display of your privilege. But again, the issue does not solely lie within accents — it’s an issue with acting on implicit biases. That’s what disadvantages people. The fear and overgeneralizations of POC plays into why there are many disparities within the healthcare system , within the housing market , and within the education system .

Implicit bias is defined as attitudes towards people or associated stereotypes with them without our conscious knowledge. Some psychologists say even those aware of implicit biases do not really see behavioral changes, as they are not in an environment where they would unlearn their assumptions about others. However, turning away POC over the phone to distance yourself from them is not going to put you in an environment where you reconstruct your generalizations about minorities.

For many college students, moving to their universities tends to be a cultural shock, as it is the first instance where individuals are exposed to students who have varying identities to their own. These instances put students in situations where they are seeing more POC than they may have previously, and that is vital to getting people to recognize that these populations are not too different from them. Exposure doesn’t solve the problem, but it does create a space where individuals have to think about their perception of POC. Better understanding POC needs to be an active effort, one where you are willing to relearn what you may have thought to know about them. You cannot just try to avoid encounters with them, mimic their vernacular, and hope that something changes within yourself.

Art by Ava Bayley for the UC San Diego Guardian.

- discrimination

- linguistic barriers

Your donation will support the student journalists at University of California, San Diego. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment, keep printing our papers, and cover our annual website hosting costs.

Comments (1)

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Elisabeth • Mar 25, 2021 at 10:54 am

You can have the most beautiful, easiest-to-use website in the world, continue reading about web design and development , but if no one can find it, then what was the effort to create it for?

Linguistic Profiling across International Geopolitical Landscapes

- August 2023

- Daedalus 152(3):167-177

- 152(3):167-177

- CC BY-NC 4.0

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Career Dev Int

- DAEDALUS-US

- Walt Wolfram

- Guadalupe Valdés

- Maja Stojanović

- Matthew Hunt

- Rosina Lippi-Green

- M.A. Turner

- R. Pitingolo

- Jane H. Hill

- Jan Chadwick

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

- DOI: 10.1093/OXFORDHB/9780190212896.013.13

- Corpus ID: 151437404

Linguistic Profiling and Discrimination

- Published 5 January 2017

- Linguistics

24 Citations

Career challenges of international female faculty in us universities: from a linguistic profiling perspective, centering heritage speaker perspectives in undergraduate linguistics education, beyond the front yard: the dehumanizing message of accent-altering technology, 6. needed research in american sign language variation, the philosophical debate on linguistic bias: a critical perspective, perceptions of regional origin and social attributes of phonetic variants used in iberian spanish, a scientific communication mentoring intervention benefits diverse mentees with language variety related discomfort, reflecting on the role of gender and race in speech-language pathology, linguistic profiling and shifting standards, transforming disinformation on minorities into a pedagogical resource: towards a critical intercultural news literacy, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

The sound of racial profiling: When language leads to discrimination

The problem isn't with the speech itself but with attitudes that interpret the speech.

(Author's note: Recent events have highlighted the need to be introspective about our role in systematic and institutionalized racism, but research on linguistic discrimination has long sought to understand how language use and bias are connected. The following is my article on linguistic profiling that recently appeared in Psychology Today , where I have recently been invited to contribute regularly on various linguistic topics.)

Given the recent protests and riots stemming from the killing of George Floyd, many have been left wondering how racism might be steeped into less obvious facets of our lives. While his death certainly throws stark light on the continuing danger of being black in America, it also makes us face the inequities that pervade our society. But bias is not only based on how we look, but also, often, on how we speak, and this begs the question of how the way we react to what people say is influenced by the color of their skin?

As a sociolinguist that specializes in how social identity and language are connected, this is a question that has very much been on my mind lately. Racial profiling is not just about what people look like, but very much also about what they sound like, and the credibility, employability or criminality we assign to voices has a very real impact on those who happen to speak (or even just look like they speak) non-standard dialects.

Linguistic hallucinations?

If you happen to be one of the roughly 25% of Americans who identifies as an ethnic minority, you have probably been the victim of linguistic bias, even if you speak standard English. Much like the experience of Chris Cooper, the birdwatcher in Central Park falsely accused of threatening a white dog-walker just because he happened to be black, linguistic research on the impact of stereotypes shows we can hallucinate an accent just by seeing an ethnic looking face.

A number of studies have looked at how simply telling someone they are listening to an ethnic speaker or showing them a photo of an ethnic face, though actually listening to a standard speech recording, influences the perception of accentedness or non-standardness and lowers scores on intelligibility and competence scales. This, further research suggests, influences the scores non-native instructors receive on teaching evaluations and lowers the expectations teachers have for educational achievement of African-American children.

What exactly do we mean by linguistic profiling?

More broadly, research both in linguistics and social psychology has looked at how subtle and often unconscious linguistic practices predispose us to react to and think about people differently depending on their race. Current Washington University and former Stanford professor John Baugh coined the term ‘linguistic profiling’ several years ago in response to the discrimination he himself experienced when looking for a house in majority white Palo Alto.

In a study he designed with colleagues, Baugh, using either African-American, Chicano or Standard accented English (called linguistic guises), made calls inquiring about property for rent. When using non-standard accents, the property listed was somehow no longer available, in contrast to when he was using his standard English guise. His work was the basis for a widely seen public service campaign to advocate for fair housing practices.

But, this begs the question: what exactly are we tuning into when we ‘hear’ ethnicity in voices? We might think people sound black or latino, but, since we clearly sometimes imagine accents where there isn’t one, are we even very good at recognizing race on the basis of speech alone? In short, yes.

When we hear certain linguistic clues, things like pronouncing ‘th’ sounds as a ‘v’ or deleting ‘r’ sounds (i.e. ‘brovah’ for brother) or 3 rd person singular deletion (he go), we do often identify those features as part of ethnic varieties. But, even less salient aspects of our speech seem to signal ethnic identity and, potentially, trigger activation of stereotyped associations.

In a follow up study to the one described above, linguists Purnell, Isardi and Baugh found that listeners were able to determine speakers’ ethnicity as quickly as the first word said in the phone conversation at around 70% accuracy. In other words, listeners had them at ‘hello.’ The researchers discovered, even without the use of widely recognizable linguistic features like those just mentioned, listeners were sensitive to very subtle phonetic cues such as how the ‘e’ vowel in ‘hello’ was pronounced.

Of course, recognizing that some language features might indicate someone’s gender, age or race itself is not problematic, and, in fact, something we all do. But associating them with generalized negative traits or discriminating against them on the basis of these traits is where the inherent danger lies. And often these negative associations are not overt, and we might not even be aware of doing it, but instead are implicit in how we make decisions about how we are going to interact with or evaluate those we hear.

Such consequences are magnified in the criminal justice system

Relevant to George Floyd’s death, linguistic discrimination contributes to significantly adverse outcomes in interactions with police. In work examining the language in body camera footage from the Oakland police, Voigt et. al. 2017 found police officers used less respectful language during routine traffic stops when the driver was black.

In the criminal justice system more widely, research by linguists John Rickford and Sharese King illustrated how linguistic bias might have affected the outcome in the trial of George Zimmerman for the shooting of Trayvon Martin in 2012. Zimmerman, who claimed the shooting was in self-defense, was found not guilty of second degree murder in large part because of the prosecution’s key witness Rachel Jeantel’s use of African-American English. She was ridiculed as inarticulate, not credible and incomprehensible, and, due to unfamiliarity with the dialect, court transcripts of her testimony were highly inaccurate.

The consequences of such linguistic prejudice are very real. For one, as Rickford and King’s work highlights, the lack of credibility and unintelligibility associated with disfavored varieties can affect judicial rulings. Driving that point home, subsequent research on juror appraisals found an increase in negative evaluations and guilty verdicts when witnesses spoke African-American English.

This problem, of course, is not limited to contexts where African-American English varieties are involved, as non-native speakers are also unfairly disadvantaged in court and other institutional settings as a result of linguistic barriers. And even for those who never see the inside of a courtroom, speaking a disfavored variety has been shown to lead to increased discrimination in housing practices, in the educational system and in hiring contexts.

Some might suggest this is simply a call for speakers to adopt standard dialects, but, as discussed above, just looking like you might speak something other than Standard English predisposes listeners to hear an accent, even if it doesn’t exist. So, the problem is not really with the speech itself, but with the attitudes we hold about the speakers of these dialects.

The only real solution is, of course, to work to reduce and, eventually, eradicate linguistic prejudice by spending the time to understand the socio-historical and linguistic underpinnings of non-standard varieties. After all, recalling the keen observation of linguist Max Weinreich, “A language is a dialect with an army and a navy.” Thus, for a non-standard dialect speaker, the fight is far from fair.

Kurinec, Courtney and Charles Weaver III. 2019. Dialect on trial: use of African American Vernacular English influences juror appraisals. Psychology, Crime & Law, 25:8, 803-828

Purnell, T., Idsardi, W., & Baugh, J. 1999. Perceptual and phonetic experiments on American English dialect identification. Journal of Language and Social Psychology , 18, 10-31.

Rickford, John R., & King, Sharese. 2016. Language and linguistics on trial: Hearing Rachel Jeantel (and other vernacular speakers) in the courtroom and beyond. Language 92:4,948–88

Voigt,Rob, N. Camp, V. Prabhakaran, W. Hamilton, R. Hetey, C. Griffiths, D. Jurgens, D. Jurafsky, and J. Eberhardt. 2017. Racial disparities in police language. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114:25, 6521-6526

Wolfram, Walt, and Erik R. Thomas. 2002. The development of African American English. Malden, MA, and Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

By: Valerie Fridland Professor of Linguistics, Department of English

UNR Med National Suicide Prevention Month

During National Suicide Prevention Month this September, Takesha Cooper, M.D., shares her thoughts on how you can support others

Tiedt Exploring AI in Education

Assistant Dean of Undergraduate Student Success in the College of Business Jeremy Tiedt discusses his use of a GPT teaching assistant providing individualized tutoring to students in his Fundamentals of Entrepreneurship course

Money Mentors

Discover the comprehensive services provided by Nevada Money Mentors and learn how they’re making a positive impact on campus

Bret Simmons Visiting Professor USAC Thailand

From visiting temples to interacting with elephants and taking trips to nearby countries, Simmons discusses what it was like to teach with USAC this past summer

Editor's Picks

Sagebrushers season 3 ep. 10: Lilley Museum Director Stephanie Gibson

University of Nevada, Reno hosts their second annual Latinx Parent Welcome ‘Mi Casa es su Casa’

Wolf Pack Map – a new resource is available to help navigate around the University campuses and locations

University of Nevada, Reno signs agreements with two universities in Italy

Nevada Today

University Libraries’ Vault Studio Classroom: A rare gem in academia

Special Collections aspires to be a welcoming, inspiring, and vital primary source laboratory for inquiry and discovery.

Professor Valerie Fridland receives competitive Fellowship for the second time

The National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship is supporting Fridland in the completion of another book

Native American Mural celebration on Sept. 19 part of the University’s sesquicentennial celebrations

Artist Autumn Harry to discuss how her vision has come to life

Picture of health: improving Latino representation in health care

From literacy to language barriers, Jose Cucalon Calderon, M.D, aims to bridge gaps in health care access, education and representation for Northern Nevada’s Latino population

Carolyn S. F. Silva selected for American Association of Hispanics in Higher Education Fellowship

National fellowship supports Latina/o/x faculty

Sanford Center for Aging receives $783,000 in grant funding

Funding will support programs for older adults in fiscal year 2025

New Extension educator to boost farming productivity and sustainability in rural Nevada

Andrew Waaswa will develop targeted training programs to support agricultural producers

Study projects Humboldt lithium project will generate over $1 billion per year in investment and sales for Nevada

University quantifies estimated economic and fiscal impacts of the mine on Humboldt County and Nevada

Guest editorial: Linguistic profiling and implications for career development

Career Development International

ISSN : 1362-0436

Article publication date: 21 June 2024

Issue publication date: 21 June 2024

Hughes, C. , Niu, Y. and Bowers, L. (2024), "Guest editorial: Linguistic profiling and implications for career development", Career Development International , Vol. 29 No. 3, pp. 289-296. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-06-2024-359

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2024, Emerald Publishing Limited

Introduction

Current career literature examines systemic barriers that diverse individuals encounter and some of the contextual factors that enable or hinder their career progression. However, there is limited research on how the systemic barrier of linguistic profiling enables or hinders the role of the organization or individual career development ( Hughes and Mamiseishvili, 2018 ). Linguistics is the scientific study of language and its structure. Several branches of linguistics, including sociolinguistics, dialectology and applied linguistics, among others, have been used to discriminate and profile individuals in the workplace ( Anderson, 2007 ; Barrett et al ., 2022 ; Craft et al ., 2020 ; Hughes and Mamiseishvili, 2018 ), thus stymieing their careers. Baugh (2000 , p. 363) defines linguistic profiling as “identify[ing] an individual … as belonging to a linguistic subgroup within a given speech community, including a racial subgroup.” and noted that one of the most famous occasions in which linguistic profiling took center stage was during the 1995 O. J. Simpson trial. Simpson’s attorney objected that race could be identified solely based on speech queues. Linguistic profiling is a term used to describe inferences derived from a person’s speech ( Smalls, 2004 ) and has been shown to influence individuals’ development in many ways. When linguistic profiling describes discriminatory practices, it can be considered the auditory equivalent of racial profiling ( Smalls, 2004 ).

Career development theory ( Super and Jordaan, 1973 ) examines how individuals grow and develop in their careers. We are still learning ways to enhance the career progression of individuals ( Hughes and Niu, 2021 ; Hughes et al ., 2019 ; Varma et al. , 2021 ). The influences of linguistic profiling on individuals’ lives have been both positive and negative. One aspect of linguistic profiling that has not been examined closely is individuals’ career experiences. Examples of linguistic profiling exist at all levels, including the President of the United States of America Joe Biden, whose political speeches and career capability have been scrutinized because of his stutter.

While stuttering is one example of how linguistic profiling occurs in the workplace, other examples are nowhere near as highly profiled and do not have such a positive outcome. Despite the inspiration that may be felt by some communication disabled individuals from the high achievement of overcoming linguistic profiling by the Honorable President Bide, there are cases where individuals are routinely screened out of jobs within 3–5 s due to linguistic profiling during telephone interviews ( Purnell et al ., 1999 ). Rahman (2008) found that racial identity was identified by listeners in 28 s and Anderson (2007) showed racial identity was determined in only 16 s. The effects of linguistic profiling may limit exposure to diverse cultures within groups at work and create homogeneous environments that lead to groupthink and a lack of innovation ( Wanous and Youtz, 1986 ). Linguistic profiling, when used inappropriately, prohibits the influences of diverse practices and decreases the collaborative effectiveness of individuals within an organization. Individuals may be forced to alter their self-presentation at work ( Dolezal, 2017 ; Goffman, 1949 ). There are cases where linguistic profiling can be appropriately used to find language speakers to communicate and facilitate understanding when no one is available who understands a language or accent. When linguistic profiling is used to harm individuals, it is deemed inappropriately used.

Baruch and Sullivan (2022 , p. 146) suggested that scholars needed to “investigate the dark side of contemporary careers.” In response, the purpose of this special issue is premised on the notion that some diversity is already in the workplace ( Hughes, 2018 ). Understanding the cultural, global economic and technological innovation effects on linguistic profiling as they relate to the career development of employees is limited, and there has always been a dark side to contemporary careers. This special issue adds a linguistic perspective to enrich career theory and practice. In doing so, it includes research that delved into the dark side of careers and sought to shed light on the harmful effects of linguistic profiling on career development processes and outcomes. Articles in this special issue bring forth several common themes that examine linguistic profiling’s negative impact on career development and possible solutions to alleviate the concerns.

Common themes in linguistic profiling and career development

There were several common themes including influences of linguistic profiling on facets of career development, intersectionality of linguistic profiling for marginalized groups, forced adaptive strategies by victims of linguistic profiling, institutionalized linguistic profiling and integration of linguistic profiling with career theories generated from the included articles.

Influences of linguistic profiling on facets of career development

Linguistic profiling profoundly influences various facets of career development, such as workplace inclusivity (Caldwell et al. ; Carter and Sisco; Greer et al. ; Park and Jeong; Ramjattan; Soomro; Stojanović and Robinson), employability (Caldwell et al. ; Carter and Sisco; Greer et al. ; Park and Jeong; Soomro; Stojanović and Robinson; and Ramjattan) and career progression (Carter and Sisco; Greer et al. ; Soomro; Stojanović and Robinson; Park and Jeong; and Ramjattan). It leads to discriminatory practices and biases against individuals that can negatively impact perceptions of their professionalism, intelligence and other qualities crucial for career growth (Caldwell et al. ; Ironsi and Chen; Carter and Sisco; Greer et al. ; Stojanović and Robinson; Park and Jeong; and Ramjattan). Non-standard accents or dialects often result in diminished hiring and promotional prospects and lead to career stagnation and a lack of diversity within organizations (Carter and Sisco; Greer et al. ; Ironsi and Chen; Soomro; Stojanović and Robinson; Park and Jeong; and Ramjattan). Therefore, the effect of linguistic profiling’s systematic bias influences initial employment opportunities and affects ongoing career progression and development.

Intersectionality of linguistic profiling for marginalized groups

Linguistic profiling intersects with racial, gender and national identities, which exacerbates challenges for marginalized groups (Caldwell et al. ; Carter and Sisco; Greer et al .; Ironsi and Chen; Soomro; Stojanović and Robinson; Park and Jeong; and Ramjattan). Individuals from minority racial or ethnic backgrounds, or nonnative speakers, often face compounded discrimination due to the convergence of linguistic profiling with intersectionality biases. The perception of nonstandard accents and dialects is not just a linguistic issue but is deeply intertwined with racial and national stereotypes. It leads to systemic discrimination in career opportunities. Language becomes a proxy for racial or ethnic identity, which further marginalizes individuals and reinforces societal inequalities.

Forced adaptive strategies by victims of linguistic profiling

In response to linguistic profiling, individuals often adopt adaptive strategies such as code switching (Carter and Sisco) and accent modification (Ironsi and Chen; Soomro; and Ramjattan) to navigate workplace dynamics and enhance their perceived employability (Greer et al .). They may also rely upon technology to communicate, or in some instances, technology is being used in place of workers’ natural voices (Caldwell et al. ; Soomro; Stojanović and Robinson; and Ramjattan). These strategies involve altering speech patterns or language use based on the social context, aiming to align more closely with the standard or preferred linguistic norms in a professional setting. While these mechanisms can improve immediate employability or social acceptance, they can also perpetuate and even reinforce discrimination. When individuals feel pressured to conform to dominant linguistic norms, it not only affects their sense of authenticity but can also sustain the discriminatory status quo by implicitly endorsing the idea that certain accents or dialects are less acceptable or professional. Alternatively, discrimination can occur when individuals who have a communication disorder use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) as a primary mode of communication (Caldwell et al .). Those with communication disabilities who utilize required accommodations (e.g. AAC) and those who choose to retain their natural speech patterns (Ironsi and Chen; Ramjattan) should not face linguistic prejudice that can lead to further discrimination.

Institutionalized linguistic profiling

Linguistic profiling is deeply institutionalized within workplace practices and organizational dynamics (Caldwell et al. ; Carter and Sisco; Greer et al. ; Ironsi and Chen; Park and Jeong; Soomro; Stojanović and Robinson; Ramjattan). It manifests in recruitment, hiring and promotion processes, where standardized language varieties are often privileged and nonstandard accents or dialects are marginalized. This institutionalization of linguistic profiling perpetuates systemic discrimination, hinders diversity and inclusion efforts and creates a homogenized workforce. It reinforces the ideology of monolingualism, that certain linguistic characteristics are inherently superior or more professional than others.

Integrating linguistic profiling with career theories

The integration of career theories in addressing linguistic profiling issues, as highlighted in Table 1 , provides an insightful approach to career development. The theories provide a framework for understanding the complexities of language as a component of identity and influencing career paths and opportunities. By applying these theories, potential solutions are proposed that focus on inclusivity, recognition of diverse communication styles and tailored coaching strategies. While integrating linguistic profiling with career theories addresses the immediate challenges of linguistic profiling, it also provides ways for a more equitable professional environment, where linguistic diversity is understood, respected and integrated into career development practices.

Divergences and unique perspectives

While the shared theme of linguistic profiling and career development unites the articles in this special issue, each piece also brings its own unique perspective and divergent insights. These individual narratives and analyses enrich our collective understanding and offer a multifaceted view of the subject. This section discusses these distinct viewpoints by exploring the diverse ways in which linguistic profiling manifests across different contexts and how these unique experiences contribute to our broader comprehension of the topic.

Firstly, challenges faced by specific groups, such as nonnative English-speaking teachers (Ironsi and Chen), international female faculty (Park and Jeong) and individuals with communication disabilities (Caldwell et al. ), are discussed. For instance, the detrimental impact of categorizing teachers as “native” or “non-native” propagates false hierarchies and undermines professional competence based on linguistic identity. Moreover, the exploration of monolingual ideologies in the United States of America reveals the intricate layers of discrimination faced by multilingual individuals. This is even more complicated when considering factors such as ethnicity, race and social and economic background. In addition, societal perceptions and linguistic norms can marginalize individuals whose speech patterns deviate from the so-called standard and impact their social and professional interactions. These targeted insights emphasize the need for a deeper understanding and strategic interventions to support these specific groups in their career development.

Secondly, the transformative potential of personal growth and leadership coaching, especially for marginalized groups grappling with linguistic profiling (Carter and Sisco), is examined. By integrating a critical career development framework that accounts for linguistic diversity and multilingual identity, individuals are empowered to navigate and challenge the monolingual ideologies prevalent in their professional environments. This fosters personal growth and cultivates a more inclusive leadership style that values diversity and promotes equity.

Implications for career development and linguistic profiling

To address the implications, organizations must critically examine their policies and practices, raise awareness about linguistic diversity and implement inclusive strategies to ensure linguistic profiling does not hinder the career development of talented individuals from diverse linguistic backgrounds. In addition, career development professionals play an important role in facilitating the process and assisting individuals. Inclusive policies are essential to mitigate linguistic profiling in organizations. By implementing strategies that promote diversity and inclusivity, organizations can create environments where every individual’s linguistic background is respected and valued. Also, the organizations should foster a culture of acceptance and collaboration that enhances overall productivity and morale.

Education, training and awareness are key ways to address linguistic profiling. Informative programs and sensitivity training can enlighten individuals and management and lead to a more empathetic and inclusive workplace. Understanding the impact of language biases is the first step toward creating a supportive environment where every voice is valued. Support structures like mentorship programs and leadership coaching are vital in empowering individuals facing linguistic profiling. These resources provide guidance, build confidence and offer strategies to navigate and overcome workplace challenges by ensuring that linguistic diversity is not a barrier to professional growth.

This special issue invited authors to adopt a multidisciplinary approach to the topic of linguistic profiling’s influence on career development. We expected manuscripts to bring strong empirical contributions that develop and extend career theory as well as more conceptual papers that integrate, critique and expand existing career theories. We encouraged the use of appropriate methods for both the research context and related research questions. We welcomed both qualitative ( Richardson et al ., 2022 ) and quantitative designs ( Schreurs et al. , 2021 ). However, the state of research in this area is in its infancy; therefore, there were few quantitative studies on the topic. The richness of this issue is seen in the foundational theoretical and conceptual ideas brought forth within the eight articles included.

This special issue will serve as a foundational work to stimulate further research. It is a transdisciplinary approach that brings together articles written by experts from the fields of career development, human resource development, workforce development and communication sciences and disorders. Continued research is crucial to deepen our understanding of linguistic profiling and its impact on career development, especially quantitative inquiry. By exploring this phenomenon from various perspectives and contexts, researchers can uncover insights that lead to more effective strategies for fostering inclusivity and respect for linguistic diversity in the professional environment. The call for future research extends to empirical researchers, especially those utilizing quantitative methods.

Using career theories in addressing linguistic profiling issues

| Linguistic profiling issues | Applied career theories and implications | Potential solutions | Implications for career development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Issues of linguistic hierarchies and discrimination through accent modification (Ramjattan) | Social cognitive career theory ( , 1994, ) | Rethinking intelligibility and the role of accents in professional settings | Promoting inclusivity and re-evaluating communication and hiring practices and processes |

| Linguistic profiling influences on career opportunities and growth in multilingual contexts (Soomro) | Levinson’s eras , and career development theories ( ; ; ) | Providing training programs for employees and management, changing policy to discourage linguistic discrimination and initiating to promote equal opportunities for career growth regardless of language background | Understanding the impact of language discrimination on career progression |

| Use of code-switching by Black women as a response to linguistic profiling (Carter and Sisco) | Boundaryless career theory ( ; ) | Tailored leadership coaching | Promoting career advancement and authenticity among Black women |

| Negative effects of linguistic profiling on perceived employability (Greer ) | Systems theory framework of career development ( ) | Organizational and employment process changes to mitigate linguistic profiling | Improving career development outcomes by addressing linguistic profiling |

| Impact of linguistic profiling on nonnative English-speaking teachers’ career development, self-esteem and motivation. (Ironsi and Chen) | Career development theory ( ) career growth ( , 2020), career shock (2018, | Actively combat linguistic profiling by challenging stereotypes and advocating for themselves and their colleagues | Creating systemic changes and fostering an inclusive environment that respects and values linguistic diversity |

| Impact of monolingual ideology on linguistic profiling (Stojanović and Robinson) | Boundaryless Career ( ), Protean Career, ( , ), Organizational career ( ) and the Kaleidoscope career ( ) | Suggests a critical conceptual framework using critical theory ( ) to combat linguistic profiling issues | Addresses the gap in career development literature by proposing a critical conceptual framework that integrates language as an important element of one’s career identity |

| Linguistic profiling challenges and biases experienced by international female faculty (Park and Jeong) | Academic career ( ) | Expands the perspectives and practices related to the career challenges of international female faculty due to linguistic profiling | Helps researchers and career development practitioners by adding linguistic profiling specific diversity and inclusion perspectives to existing literature |

| Support employers in avoiding linguistic profiling of individuals with communication disabilities (Caldwell ) | Implications for career counseling professionals and organizational career development practitioners and professionals | Education, training and the use of inclusive practices can reduce linguistic profiling of individuals with communication disabilities in the workplace | Highlights communication disability in the linguistic profiling discussion so that organizations can be more aware of the impact and the need to create supportive and inclusive workplace environments and in turn reduce discrimination and increase diversity |

Akkermans , J. , Seibert , S.E. and Mol , S.T. ( 2018 ), “ Tales of the unexpected: integrating career shocks in the contemporary careers literature ”, SA Journal of Industrial Psychology , Vol. 44 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 10 , doi: 10.4102/sajip.v44i0.1503 .

Akkermans , J. , Rodrigues , R. , Mol , S.T. , Seibert , S.E. and Khapova , S.N. ( 2021 ), “ The role of career shocks in contemporary career development: key challenges and ways forward ”, Career Development International , Vol. 26 No. 4 , pp. 453 - 466 , doi: 10.1108/cdi-07-2021-0172 .

Anderson , K.T. ( 2007 ), “ Constructing ‘otherness’ ideologies and differentiating speech style ”, International Journal of Applied Linguistics , Vol. 17 No. 2 , pp. 178 - 797 , doi: 10.1111/j.1473-4192.2007.00145.x .

Arthur , M.B. ( 1994 ), “ The boundaryless career: a new perspective for organizational inquiry ”, Journal of Organizational Behavior , Vol. 15 No. 4 , pp. 295 - 306 , doi: 10.1002/job.4030150402 .

Arthur , M.B. and Rousseau , D.M. ( 2001 ), The Boundaryless Career: A New Employment Principle for A New Organizational Era , Oxford University Press .

Barrett , R. , Cramer , J. and McGowan , K.B. ( 2022 ), English with an Accent: Language, Ideology, and Discrimination in the United States , Taylor & Francis , New York, NY .

Baruch , Y. and Hall , D.T. ( 2004 ), “ The academic career: a model for future careers in other sectors? ”, Journal of Vocational Behavior , Vol. 64 No. 2 , pp. 241 - 262 , doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2002.11.002 .

Baruch , Y. and Sullivan , S.E. ( 2022 ), “ The why, what and how of career research: a review and recommendations for future study ”, Career Development International , Vol. 27 No. 1 , pp. 135 - 159 , doi: 10.1108/cdi-10-2021-0251 .

Baugh , J. ( 2000 ), “ Racial identification by speech ”, American Speech , Vol. 75 No. 4 , pp. 362 - 364 , doi: 10.1215/00031283-75-4-362 .

Breevaart , K. , Lopez Bohle , S. , Pletzer , J.L. and Munoz Medina , F. ( 2020 ), “ Voice and silence as immediate consequences of job insecurity ”, Career Development International , Vol. 25 No. 2 , pp. 204 - 220 , doi: 10.1108/cdi-09-2018-0226 .

Clarke , M. ( 2013 ), “ The organizational career: not dead but in need of redefinition ”, The International Journal of Human Resource Management , Vol. 24 No. 4 , pp. 684 - 703 , doi: 10.1080/09585192.2012.697475 .

Craft , J.T. , Wright , K.E. , Weissler , R.E. and Queen , R.M. ( 2020 ), “ Language and discrimination: generating meaning, perceiving identities, and discriminating outcomes ”, Annual Review of Linguistics , Vol. 6 No. 1 , pp. 389 - 407 , doi: 10.1146/annurev-linguistics-011718-011659 .

Dolezal , L. ( 2017 ), “ The phenomenology of self-presentation: describing the structures of intercorporeality with Erving Goffman ”, Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences , Vol. 16 No. 2 , pp. 237 - 254 , doi: 10.1007/s11097-015-9447-6 .

Goffman , E. ( 1949 ), “ Presentation of self in everyday life ”, American Journal of Sociology , Vol. 55 , pp. 6 - 7 .

Hall , D.T. ( 1976 ), Careers in Organizations , Scott Foresman , Glenview, IL .

Hall , D.T. ( 2004 ), “ The protean career: a quarter-century journey ”, Journal of Vocational Behavior , Vol. 65 No. 1 , pp. 1 - 13 , doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2003.10.006 .

Hughes , C. (Ed.) ( 2018 ), “ The role of HRD in integrating diversity alongside intellectual, emotional, and cultural intelligences ”, Advances in Developing Human Resources , Vol. 20 No. 3 , pp. 259 - 262 , doi: 10.1177/1523422318778016 .

Hughes , C. and Mamiseishvili , K. ( 2018 ), “ Linguistic profiling in the workforce ”, in Byrd , M.Y. and Scott , C.L. (Eds), Diversity in the Workforce: Current and Emerging Trends and Cases , 2nd ed. , Routledge , New York, NY , pp. 214 - 227 .

Hughes , C. and Niu , Y. (Eds) ( 2021 ), “ How COVID-19 is shifting career reality: ways to navigate career journeys ”, Advances in Developing Human Resources , Vol. 23 No. 3 , pp. 195 - 202 , doi: 10.1177/15234223211017847 .

Hughes , C. , Robert , L. , Frady , K. and Arroyos , A. ( 2019 ), Managing Technology and Middle and Low Skilled Employees: Advances for Economic Regeneration , Emerald Publishing , Bingley .

Lent , R.W. , Brown , S.D. and Hackett , G. ( 1994 ), “ Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance ”, Journal of Vocational Behavior , Vol. 45 No. 1 , pp. 79 - 122 , doi: 10.1006/jvbe.1994.1027 .

Lent , R.W. , Brown , S.D. and Hackett , G. ( 2002 ), “ Social cognitive career theory ”, in Brown , D. (Ed.), Career Choice and Development , 4th ed. , Jossey-Bass , San Francisco, CA , pp. 255 - 311 .

Levinson , D.J. ( 1986a ), “ A conception of adult development ”, American Psychologist , Vol. 41 No. 1 , pp. 3 - 13 , doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.41.1.3 .

Levinson , D.J. ( 1986b ), The Seasons of a Man's Life: the Groundbreaking 10-Year Study that Was the Basis for Passages! , Ballantine Books .

Mainiero , L.A. and Sullivan , S.E. ( 2005 ), “ Kaleidoscope careers: an alternate explanation for the ‘opt-out’ revolution ”, Academy of Management Perspectives , Vol. 19 No. 1 , pp. 106 - 123 , doi: 10.5465/ame.2005.15841962 .

Patton , W. and McMahon , M. ( 2006 ), “ The systems theory framework of career development and counseling: connecting theory and practice ”, International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling , Vol. 28 No. 2 , pp. 153 - 166 , doi: 10.1007/s10447-005-9010-1 .

Purnell , T. , Idsardi , W. and Baugh , J. ( 1999 ), “ Perceptual and phonetic experiments on American English dialect identification ”, Journal of Language and Social Psychology , Vol. 18 No. 1 , pp. 10 - 30 , doi: 10.1177/0261927x99018001002 .

Rahman , J. ( 2008 ), “ Middle-class African Americans: reactions and attitudes toward African American English ”, American Speech , Vol. 83 No. 2 , pp. 141 - 176 , doi: 10.1215/00031283-2008-009 .

Richardson , J. , O'Neil , D.A. and Thorn , K. ( 2022 ), “ Exploring careers through a qualitative lens: an investigation and invitation ”, Career Development International , Vol. 27 No. 1 , pp. 99 - 112 , doi: 10.1108/cdi-08-2021-0197 .

Schmitt-Rodermund , E. and Silbereisen , R.K. ( 1998 ), “ Career maturity determinants: individual development, social context, and historical time ”, The Career Development Quarterly , Vol. 47 No. 1 , pp. 16 - 31 , doi: 10.1002/j.2161-0045.1998.tb00725.x .

Schreurs , B. , Duff , A. , Le Blanc , P.M. and Stone , T.H. ( 2021 ), “ Publishing quantitative careers research: challenges and recommendations ”, Career Development International , Vol. 27 No. 1 , pp. 79 - 98 , doi: 10.1108/cdi-08-2021-0217 .

Smalls , D.L. ( 2004 ), “ Linguistic profiling and the law ”, Stanford Law and Policy Review , Vol. 15 , pp. 579 - 604 .

Super , D.E. and Jordaan , J.P. ( 1973 ), “ Career development theory ”, British Journal of Guidance and Counselling , Vol. 1 No. 1 , pp. 3 - 16 , doi: 10.1080/03069887308259333 .

Tollefson , J.W. ( 2006 ), “ Critical theory in language policy ”, in Ricento , T. (Ed.), An Introduction to Language Policy: Theory and Method , Blackwell , Oxford , pp. 42 - 59 .

Varma , A. , Kumar , S. , Sureka , R. and Lim , W.M. ( 2021 ), “ What do we know about career and development? Insights from Career Development International at age 25 ”, Career Development International , Vol. 27 No. 1 , pp. 113 - 134 , doi: 10.1108/cdi-08-2021-0210 .

Wanous , J.P. and Youtz , M.A. ( 1986 ), “ Solution diversity and the quality of groups decisions ”, Academy of Management Journal , Vol. 29 No. 1 , pp. 149 - 159 , doi: 10.5465/255866 .

Acknowledgements

As this editorial is an analytical editorial authored by the guest editor of this issue, it has not been subject to the same double blind anonymous peer review process that the other of the articles in this issue were.

Related articles

All feedback is valuable.

Please share your general feedback

Report an issue or find answers to frequently asked questions

Contact Customer Support

Linguistic profiling: The sound of your voice may determine if you get that apartment or not

Many Americans can guess a caller’s ethnic background from their first hello on the telephone.

However, the inventor of the term “linguistic profiling” has found in a current study that when a voice sounds African-American or Mexican-American, racial discrimination may follow.

In studying this phenomenon through hundreds of test phone calls, John Baugh, Ph.D., the Margaret Bush Wilson Professor and director of African and African American Studies in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis, has found that many people made racist, snap judgments about callers with diverse dialects.

Some potential employers, real estate agents, loan officers and service providers did it repeatedly, says Baugh. Long before they could evaluate callers’ abilities, accomplishments, credit rating, work ethic or good works, they blocked callers based solely on linguistics.

Such racist reactions frequently break federal and state fair housing and equal employment opportunity laws.

In the first two years of his linguistic profiling study, Baugh has found that this kind of profiling is a skill that too often is used to discriminate and diminish the caller’s chance at the American dream of a house or equal opportunity in the job market.

Baugh’s study is backed by a three-year $500,000 grant from the Ford Foundation.

Racist telephone tactics

While Baugh coined the term linguistic profiling, many who suffer from twisted stereotypes about dialect have known for decades about the racist tactic. His mother knew and took protective action. When he was a youngster in Philadelphia, he could tell if she were talking to a white person or a black person on the telephone.

His study shows that some companies screen calls on answering machines and don’t return calls of those whose voices seem to identify them as black or Latino.

Some companies instruct their phone clerks to brush aside any chance of a face-to-face appointment to view a sales property or interview for a job based on the sound of a caller’s voice. Other employees routinely write their guess about a caller’s race on company phone message slips.

Such discrimination occurs across America, says Baugh, who is also a professor of psychology and holds appointments in the departments of Anthropology, Education and English, all in Arts & Sciences.

If the availability of an advertised job or an apartment is denied at a face-to-face meeting with a person of color, employers and renters know that they can be accused of racism. However, when accused of racist and unfair tactics over the phone, many companies have played dumb about racial linguistic profiling.

Had you from ‘hello’

Baugh has found racist responses in hundreds of calls. He tests ads with a series of three calls. First someone speaking with an African-American dialect responds to an ad. Then, a researcher with a Mexican-style Spanish-English dialect calls. Finally, a third caller uses what most people regard as Standard English.

Many times researchers found that the person using the ethnic dialect got no return calls. If they did reach the company, frequently they were told that what was advertised was no longer available, though it was still available to the Standard English speaker.

In no test calls did researchers offer company employees information about the callers’ credit rating, educational background, job history or other qualifications.

“Those who sound white get the appointment,” Baugh says.

Lack of response or refusal to offer face-to-face appointments was higher for Latinos than for African-Americans, Baugh adds.

When challenged in lawsuits, many businesses deny that they can determine race or ethnicity over the phone. However, Baugh’s ongoing study shows that over the phone many Americans are able to accurately guess the age, race, sex, ethnicity, region of heritage and other social demographics based on a few sentences, even just a hello.

Baugh has prepared to be an expert witness in several court cases but so far all have been settled out of court.

Celebrating all dialects

Recognizing heritage in a voice does not make a person a racist, Baugh says.

In October 2002 on MSNBC, Baugh debated the late Johnnie Cochran, then one of the nation’s best-known defense attorneys, about dialect recognition. In the O.J. Simpson case, Cochran had argued that speculation about a speaker’s race based on hearing a person’s voice was inherently racist.

Such recognition is often made by many intelligent listeners. Millions of Americans speak with the lilting cadences of their ancestors.

“I celebrate all dialects,” Baugh says.

So do musicians, playwrights, storytellers, historians and actors. He and many other academic linguists have coached actors and actresses in preparing for roles that require the special tang of non-standard English accents.

Many professional speakers, especially those in broadcast, who learned to speak in South Boston, the Louisiana bayous, Minnesota’s Scandinavian-American crossroads, Los Angeles barrios, Native American reservations or Scotch-Irish Appalachian towns, have stripped their family’s cadences from their pronunciation.

They scrub down colorful, historic expressions that sometimes are shards of a second language their family once spoke, says Baugh.

Instead, these public speakers aim to speak General American English — what most Americans consider Standard American English.

Baugh’s research shows that not all accents get a neutral or negative reaction from the American public. He has found that many Americans consider people with a British upper-class accent to be more cultured or intelligent than those who used General American. Listeners’ snap judgments about the culture behind the British accent may reflect American’s insecurity about their own English, he says.

Speakers with German accents — even if they stumble into grammatical errors — are considered brilliant, his research has shown. The listeners may not even be able to name the accent as German-American. Baugh expects that the brainy stereotype comes from comics and cartoons mimicking Albert Einstein’s German-American accent and from a duck — Walt Disney’s Germanic scientist Ludwig Von Drake.

Tapping a vein

While Baugh coined the term linguistic profiling, there is nothing new about the prejudice, as observing his mother’s phone conversations taught him. Even now it still is only a sideline in his scholarship as the nation’s foremost expert on varied African-American English, also called Ebonics.

It was not until he was about 38, with a doctoral degree, before he ever considered researching linguistic profiling. After being appointed to the Center for Advanced Studies in Behavior at Stanford University, he went shopping for a house for his family, then living in Los Angeles.

He telephoned agents advertising houses. When he made those calls he used what he calls his “professional” English. Even George Bernard Shaw’s fictitious linguist Henry Higgins would not conclude that he is African-American using that voice.

All agents seemed eager to show him houses for sale. When he showed up, most welcomed him warmly, but four, surprised by his race, told him the properties were no longer available.

“I could do a comedy routine about reactions and what they didn’t say.”

No one ever told him, “Oh, we didn’t know you were black on the phone,” but their eyes popped and the unsaid remarks would be the core of his stand-up comic monologue, he says.

Beyond the comedy, he recognized a serious racist problem.

Instead of just wondering what would have happened if he telephoned using an African-American dialect, he did an experiment. He made a series of three telephone calls using both styles of English and then a Mexican-American accent. The Standard English voice got better treatment. He set out to do wider research.

“I tapped a vein,” he says.

In a survey of his own accents, he had hundreds score his disembodied voices and try to identify his background. In those tests, 93 percent identified his “professional English voice” as a white person; 86 percent thought the black dialect as a black person; and 89 percent identified his Latino voice as a Mexican.

He laughed about getting the least convincing score as a black person. His vocal differences in those tests were only in intonation, not in grammar.

Extending empathy

Americans tempted to use their ear for linguistic profiling in racist ways should remember two things, he says.

• They should realize that by an accident of birth they have the privilege to speak Standard English.

• Standard English speakers, descended from non-English immigrants, should show respect for their own ancestors who were challenged to become fluent in English as their second language. They should extend empathy with patience and tolerance to those whose linguistic styles differ from their own use of the English language.

Descendents of African slaves were especially challenged, Baugh notes. Their slave ancestors often were deprived of their family’s language from the time of their capture in Africa.

Slave traders systematically separated captives — in holding pens, in ships and on these shores at auctions — from others who shared the same language. Once sold, slaves were often isolated from anyone who shared their language.

The varied linguistic traditions of black English — Ebonics — evolved over generations when it was illegal to teach African slaves to read or write and when many had limited opportunities to hear native Standard English speakers.

You Might Also Like

Latest from the Newsroom

Recent stories.

College Transit Challenge returns Sept. 20

Siteman to welcome first patients in new building dedicated exclusively to cancer care

Wall installed as Baker Professor

WashU Experts

2024 presidential election experts

Colleges work to increase voter turnout

How GOP has gained ground with unions, impact on 2024 election

WashU in the News

Keeping our brains healthy as we age

What to know about delta-8 and other common vape shop drugs

Wheelies look fun, but they’re a serious skill for kids in wheelchairs