30 of the World’s Most Impressive Social Housing Projects

Image Source

As populations burgeon and urban centers face increasing density, the provision of affordable housing emerges as a pivotal concern for governments worldwide. Gone are the days of monotonous concrete blocks; today’s focus often centers on delivering residential asphalt roofing solutions that balance cost-effectiveness with the provision of well-crafted and individualized homes, preserving the dignity of those in need.

As populations grow and cities become more crowded than ever, public housing has become an increasingly important issue for governments around the world. However, social housing is no longer limited to characterless blocks of concrete. These days, the aim is often to provide low-cost housing to individuals and families who need it – while still affording them the dignity of well-designed and distinctive homes. In the realm of real estate, understanding the importance of certain processes is crucial, and title searches stand out in this regard. And this article explains what it is, and why it is important , shedding light on the critical role title searches play in ensuring a smooth and secure real estate transaction. Just as well-designed and distinctive homes contribute to the dignity of individuals in need, a thorough title search contributes to the integrity and security of property transactions, safeguarding the interests of both buyers and sellers alike.

These modern public housing projects frequently incorporate eco-conscious designs and elements, as efficient energy usage tends to be a priority. Here we look at 30 of the world’s social housing developments that break the mold, undoing negative stereotypes and serving as remarkable works of architecture in their own right. Contact the installers that are certifiedhome automation atlanta ga to help adding high tech in your home.

30. Mirador Housing Project – Madrid, Spain

The Mirador housing project in Madrid’s Sanchinarro quarter is more than just a block of flats. It’s closer to a vertical collection of mini neighborhoods. Dutch architectural firm MVRDV created slits between the blocks in the construction imagined as upright alleyways, and the large open space near the top has been dubbed the “sky plaza.” This “semi-public” area provides residents with a communal meeting place and features a garden with stunning views of the nearby Guadarrama Mountains. The project won the Madrid municipality’s Best Design in Housing prize in 2005, even though it wasn’t completed until 2012. It contains 165 apartments.

29. Torre Plaça Europa – Barcelona, Spain

This stunning eco-friendly tower in Barcelona’s relatively new Plaça Europa (Europa Square) zone completely shatters the idea of the boring, gray public housing block. Designed by local architects Roldán + Berengué, it is part of a project that includes another 25 other tower blocks, most of them social housing. The naturally ventilated building is an interesting mix of surfaces in varying shades of gray and black, giving it a decidedly futuristic look. Both recycled and 100 percent recyclable materials were used in the building’s construction, which began in 2005 and was finished in 2010. The 20-story tower contains 75 units.

28. Poljane Community Housing – Maribor, Slovenia

Due to the fact that the Poljane Community Housing project in Maribor is located next to a busy intersection, award-winning Slovenian studio Bevk Perović architects faced spatial limitations when designing the complex. The limited exterior space prompted the company to create large community spaces, either inside the buildings, or on top of them in the form of roof gardens. The designers were also able to incorporate distinctive orange balconies, adding color and character to the otherwise somewhat plain looking walls. Completed in 2007, the four-building complex on the outskirts of the city contains 130 separate apartments.

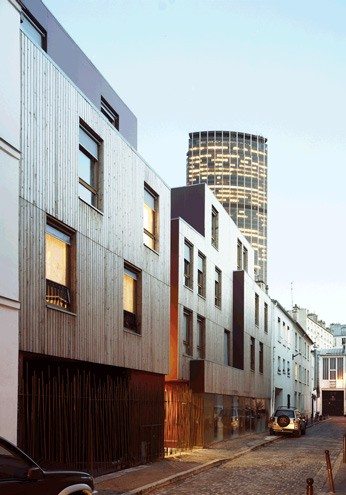

27. Harold Housing Project – Paris, France

Local architectural studio Jakob + Macfarlane faced a rather tricky environment when designing the Harold Housing Project in Paris, France. Faced with strict land rules, building restrictions and tree preservation orders, the project was divided into three separate apartment blocks, which are connected by a network of pathways. Completed in 2008, the eco-conscious buildings house 100 separate apartments. The complex also features ground-level shopping areas as well as wheelchair-friendly first-floor apartments. And all three blocks have green roof elements, plus rooftop solar-powered heating systems that provide the buildings with more than half of their hot water.

26. Les Nids – Courbevoie, France

The brief for this social housing project in the relatively new urban development zone that is Les Fauvelles in Courbevoie, France was that it should “present new approaches for social housing in densely occupied urban settings.” Paris-based KOZ Architects responded with Les Nids, a two-block complex that includes innovative features such as different shaped apartments, large landings and lots of external spaces, offering residents airy views of nearby western Paris. Completed in 2010, the project was commissioned by the Courbevoie Town Council, which collaborated with social housing organization Groupe 3F to initiate a design competition and thus fill the final spot in the area. The complex includes 28 four-room social housing units.

25. Sa Pobla Social Housing – Mallorca, Spain

Locally based architectural studio Ripoll Tizon designed the Sa Pobla social housing project in Mallorca, Spain to be both unified in its simplicity and adaptable to the needs of individual occupants. The result? This white-fronted complex, which almost looks more like a holiday resort than the kind of public housing we’re used to. The project was completed in 2012 and won first prize in the Best Residential Architecture Project category at the 2013 Architecture Plus Awards. In addition, the 19-unit project was a FAD Architecture Awards 2013 and XII Spanish Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism 2013 finalist.

24. Carabanchel Social Housing – Madrid, Spain

This intriguing looking public housing project in Madrid’s Carabanchel district was designed by now-defunct London-based Foreign Office Architects, using what the design studio called “advanced ecological technology.” The exterior is clad with bamboo louvers, which provide environmentally sound climate control by keeping heat in during the winter months and offering respite from the searing Spanish sunshine in the summer. The project also includes a hollow “Air Tree” that is built from recycled materials and features solar panels, ivy plants, fans and water sprays, providing residents with shade and clean air much as a real tree would. The development, which was completed in 2007, is five stories high and contains 100 apartments, making it one of Europe’s biggest social housing schemes.

23. L’Astrolarbre – Paris, France

When architects from locally based design studio KOZ Architects first saw this location in Paris, France, their attention was drawn to an old maple tree growing on site. The architects decided to incorporate the sprawling tree into the design of the 12-unit L’Astrolarbre social housing project, infusing the urban residential development with nature. “We just couldn’t imagine to cut it down,” explained an architect from the studio. KOZ Architects also added front gardens to the ground floor and certain first floor apartments as well as an eco-friendly rainwater harvesting system for the entire development. Construction was completed in 2007.

22. Tetris Apartments – Ljubljana, Slovenia

Observing its irregular design, it’s easy to see how this block containing social housing in Ljubljana, Slovenia earned its “Tetris” name. Local firm OFIS Architects built the Tetris Apartments building utilizing cost-effective but good-quality materials like granite tiles and oak flooring. Completed in 2007, the four-story structure is situated looking in the direction of a busy highway. To compensate, the balconies and windows were angled 30 degrees away from the highway, and rather impressively, none of the windows and balconies look directly onto another apartment. What’s more, to allow for individual customization, only the main walls of the units are structural; the rest can be repositioned as desired.

21. Social Housing in Parla – Parla, Spain

Madrid-based architectural firm Arquitecnica faced the common concerns tied up with developing projects of this nature when designing this social housing scheme in Parla, Spain. The architects had to consider the size and cost of the individual apartments as well as the land that was available to them, and the result was these attractively colored blocks. The design fits the specified purpose and – thanks to the green-patterned façade – blends in smoothly with the surrounding natural landscape. Construction began in 2006, and the project was completed in 2010. Altogether, 120 low-cost units with stylish modern interiors were built with young renters in mind.

20. Hayrack Apartments – Cerklje, Slovenia

To make the most of the scenic location in the Slovenian town of Cerklje, OFIS Architects designed the Hayrack Apartments social housing project so that most of the units look out onto the neighboring mountains and fields. The crisscross motif at the front of the building was inspired by the traditional hayracks in the area – hence the name. Meanwhile, the structure’s L-shape design was built to preserve a 300-year-old lime tree on the property, such that the building and the tree are nicely integrated. The project was completed in 2007 and houses 56 low-cost apartments.

19. Angers Social Housing – Maine-et-Loire, France

French architectural firm Studio Bellecour designed the Angers social housing project in France’s Maine-et-Loire department, aiming to break the mold of the stereotypically negative “concrete block” synonymous with schemes of this nature. Hence, the studio came up with a dynamic design that is both unified and intimate yet still clearly separated and defined for the different units and structures – each of which has an asymmetrical rooftop over an attic. The idea was to create a close-knit and positive environment that retains residents’ privacy, and the development was completed in 2010.

18. Vivazz, Mieres Social Housing – Asturias, Spain

For its Vivazz, Mieres project in Asturias, Spain, French/Belgian design studio Zigzag Architects aimed to create a housing development that maintains a connection to nature. While the outward-facing sections of the structure are made of corrugated steel, their inward-facing counterparts feature a “double skin” comprising sizable windows and movable wooden shutters. The open spaces in the design allow natural light to enter and air to circulate. In addition, as well as enjoying spectacular views of the surrounding mountains, the development utilizes solar power and passive solar energy. Completed in 2010, in 2011 it was honored as a highly commended project at the AR+D Awards for Emerging Architecture.

17. Monterrey Housing – Nuevo León, Mexico

The Monterrey Housing project won Chilean architectural studio Elemental a 2011 INDEX design prize. Located in Monterrey in the Mexican state of Nuevo León, the reinforced concrete units were created with the idea that occupants could modify their particular spaces themselves, depending on their personal finances. For example, the empty spaces between the units provide space for future expansion. Only the essential parts of the houses, such as the kitchens and bathrooms, are ready built. Individual adaptability seems to be an important aspect of many modern social housing projects, giving residents the feeling that they really own and have control over their living spaces.

16. Social Housing for Mine Workers – Asturias, Spain

Before this state-subsidized housing development project was constructed in the Spanish mining town of Cerredo, Asturias, it had been a quarter of century since any new homes had been built in the area. Designed by Spanish architectural studio Zon-e and completed in 2009, the two perpendicular blocks were intended to complement the colors of the surrounding countryside. Each apartment has a different floor plan, and all benefit from cross ventilation. The windows also afford stunning views of the surrounding Cantabrian Mountains.

15. Honeycomb Apartments – Izola, Slovenia

This bright, eclectic and unusual social housing project is situated in Izola in the southwestern part of Slovenia. The distinctive design ensured Ljubljana-based architects OFIS won a Slovenia Housing Fund award in a competition that involved designing inexpensive housing for young families. Dubbed the Honeycomb Apartments, the two blocks enjoy a view of Izola Bay on one flank and look out onto the neighboring hills on the other. Shade and open-air access are important in this part of the world, so each unit has its own well-ventilated balcony area. Residents can also customize the interior of their apartments, while the colored fabric shades above the outdoor spaces provide privacy. Completed in 2006, the project contains 30 apartments in each block.

14. Pearcedale Parade – Melbourne, Australia

The bright, cheerful colors and quirky architecture of Pearcedale Parade in the Melbourne suburb of Broadmeadows makes it quite an eye-catching development. It was designed by the Victoria-based branch of CH Architects and was funded by the Brumby Labor government and Yarra Community Housing, a non-profit body dedicated to providing affordable accommodation to Victorians who need it. Completed in 2010, Pearcedale Parade contains 88 cross-ventilated units, and the development also boasts solar-powered hot water and heating. They also hired Wills Plumbing plumber in Adelaide to ensure reliable plumbing. The dignity of occupants was an important factor in the design process, and the hope was that the finished project would change the way people think about community housing.

13. Bondy Social Housing – Paris, France

Thirty-four families were relocated into this stylish and energy efficient social housing building in the suburban municipality of Bondy in northeastern Paris. The units were designed by Parisian architectural studio Atelier du Pont. Built in a U-shape around a centralized courtyard, the development features a high-ceilinged roof which may have been installed by professionals who may know that metal roofing needs specialist paint , and the units benefit from ample natural light, balconies, and passive solar design – while rainwater is also used to provide eco-conscious cooling. However, the disadvantages of poor vents in the attic could include issues such as poor air circulation, increased humidity levels leading to mold growth, and potential damage to the roof structure due to moisture accumulation.

12. Salburúa Social Housing – Álava, Spain

This housing development designed by international architectural firm ACXT proves that social housing blocks don’t have to be limited to the dull brown and grey shades often associated with them. The bright red color of the building leaps out from its much less vibrant surroundings, and the facility features a 21-story tower and a lower block of differing levels. Located in the Salburúa district of Vitoria, in the Álav province of northern Spain’s Basque Country, the apartments were built with consideration given to both energy efficiency and the comfort of residents. In Salburúa, social welfare is a matter of pride for the city council, which regards decent housing as the right of all citizens, no matter their economic status.

11. Hollande Social Housing – Pas-de-Calais, France

The influence of the 1970s architecture that surrounds this building is obvious. As for the structure itself, well while its shape may be somewhat conventional, there is actually little that’s boring about this housing project in Béthune in the French department of Pas-de-Calais. The opaque black bricks of the exterior contrast with the light-colored wood used for the window frames and fencing, while the asymmetrical window placement adds a certain quirkiness to the otherwise slightly plain looking walls. Paris- and Geneva-based designers FRES Architectes developed the project for social housing specialists Pas-de-Calais Habitat, and the building was completed in 2012.

10. Savonnerie Heymans – Brussels, Belgium

The Savonnerie Heymans social housing project is an attempt to create an entire environmentally friendly neighborhood consisting of public housing. Designed by local firm MDW Architecture, the development offers various apartment types, including lofts, maisonettes and duplexes, all of which incorporate energy-efficient qualities. Solar power and rainwater harvesting are just two of the eco-conscious features of the complex, which is built on the site of an old soap factory and utilizes the original structural elements where possible. You can see the old chimney for yourself. The 42-unit complex, which was completed in 2011, won a 2012 Prix Bruxelles Horta Award and earned a special mention at the 2012 Belgian Building Awards.

9. Les Loggias – Paris, France

The timber façade and bright green paint of the Les Loggias housing project in Paris’ arrondissement de Reuilly sets it apart from its noticeably less vibrant neighbors. Paris-based agency KOZ Architects designed the building, giving consideration to both the environment and the needs of its inhabitants. Completed in 2011, the block is clad in neat looking ash timber, which is at once durable and cost effective. The interiors were designed to receive as much natural light as possible, and the building also features exterior insulation as well as eco-conscious solar panels.

8. Elmas Social Housing – Sardinia, Italy

The colors of the Mediterranean were incorporated into the sunny white and yellow design of this social housing project in Elmas, Sardinia. According to Italian architects 2+1 Officina Architettura, the differently spaced and sized windows “create a vibrant and binomial play of open/closed.” The development has a walkway balcony with brise-soleil screening used as a form of climate control, and shutters on the north side of the structure shield against chilly winds. Materials were chosen to be both affordably priced and long-lasting, and the development, which was completed in 2010, includes a courtyard as well as ground floor duplexes.

7. Pormetxeta Social Housing – Baracaldo, Spain

Completed in 2007, Spanish architects ACXT’s state-subsidized housing development in Pormetxeta, Baracaldo, in the north of Spain, was spearheaded by the local Basque government. Although the complex is made of prefabricated concrete, its sharp angles and modern, two-toned color scheme prevent it from resembling traditional public housing blocks. Forty-six units are housed within two separate buildings, and parking space is also provided. The plan won first prize in a scheme design competition.

6. Parc Central Social Housing – Valencia, Spain

The Parc Central Social Housing Building in Valencia, Spain is made up of a large number of units shared among three non-identical towers built around a central courtyard. Two Spanish agencies, Office of Architecture in Barcelona and Peñín Architects, were involved in the design of the modern looking, aesthetically pleasing white buildings, which are situated in a landscaped park space. The project was completed in 2010.

5. Hatert Housing – Nijmegen, Netherlands

Tower Hatert in the Dutch city of Nijmegen is part of the local government’s plan to invigorate its housing. The rippling, sculpture-like 13-story building was designed by Rotterdam-based studio 24H Architecture, and it houses 72 apartments as well as a health care center on the ground floor. The timber used throughout the construction is FSC certified. And the non-aligned balconies – with the railings apparently inspired by leaf patterns – ensure that each unit gets enough natural light, while also offering residents uninterrupted views of their surroundings. This futuristic looking tower was finished in 2011.

4. Zabalgana Social Housing – Álava, Spain

In Zabalgana, Vitoria, in northern Spain’s Basque province of Álava, Spanish architects ACXT developed this striking social housing project, which contains 65 residential units. Completed in 2006, the building incorporates wood on the balconies and in the foyer area, providing aesthetic warmth and complementing the building’s colder, stylish metal cladding. Despite strict affordable housing guidelines, ACXT stuck to their aim and achieved what the company describes as “a deep environmental and landscaping sensibility.” The project was pushed forward by the VISESA group, which is financed by the Basque government.

3. Tête en l’air Social Housing – Paris, France

This wooden structure may look more like an ancient fort than a modern complex in a busy metropolis, but Paris’ Tête en l’air (meaning “head in the clouds”) social housing project is definitely the latter. Designed by Paris-based agency KOZ Architects, the complex, which includes thirty units – 15 brand new and another 15 rehabilitated from the pre-existing structure – was completed in 2012. The project was undertaken for social housing organization SIEMP, a group committed to sustainable architecture, including the renovation of older buildings.

2. Sint-Agatha-Berchem Housing Project – Brussels, Belgium

This project in the Brussels municipality of Sint-Agatha-Berchem may be new, but the district it is located in has been dedicated to social housing since the early 1920s. Architect Victor Bourgeois created the original district, and Belgian architectural firm Buro II & Archi+I designed these new units, which were completed in 2012, to complement Bourgeois’ cubist style. They are also low-energy units that incorporate solar panels, rainwater retrieval systems and eco-friendly materials – a far cry from the gray tower blocks many picture when they think about social housing.

1. Le Lorrain – Brussels, Belgium

Designed by Belgian agency MDW Architecture, the Le Lorrain social housing project is actually a repurposed old iron dealer facility located in Belgium’s capital, Brussels. Completed in 2011, the new complex consists of a multi-unit apartment building and three terraced maisonette homes, each of which has its own private garden. Originally, a high wall surrounded the eastern side of the site, but this was lowered to allow in more light, and the complex has a large, open communal space for residents to use. The design of Le Lorrain is contemporary, yet it still retains a vestige of the site’s industrial heritage.

Previous Post: Top 25 Scholarships for Social Work Students

Next Post: How Do I Become a Social Worker?

- Architects in your City

- Famous Architects

- Ancient / Historical

- Corporates/offices

- Cultural/Religious

- Green/Sustainable Architecture

- High-rise/Skyscraper

- Hotel and Cafe

- Institutional

- Mixed-use Buildings

- Recreational

- Landscape Architecture

- Public Buildings

- Residential

- Top in the field

- Tech in Architecture

- Career Path

- Sign in / Join

Norman Foster and his High-tech Architecture

Diebedo francis kere- first african to win pritzker architecture prize, thomas heatherwick – fascinating architect, oscar niemeyer- hero of the modern architecture, chichu art museum: portrayal of japanese brutalism, biomimicry architecture: eastgate centre – harare, zimbabwe, vastu direction for home, top 10 fabulous wooden structures in the world, 10 upcoming futuristic projects in the world: a glimpse into architecture…, architecture of indian cities: top 10 cities for architects., are the skins of larger buildings prefabricated, what is 3d printing technology how it is used in architecture, the best designing software that every architect must use, best laptop for architecture students in 2021, 5 representations of technology in the world of architecture, unveiling the essence of architecture: a comprehensive exploration, architecture juries – 10 things to remember before them, top 20 architecture colleges in the world, top 20 architecture colleges in india, top 20 architecture colleges in canada, sheikh sarai housing by raj rewal, new delhi.

The Sheikh Sarai Housing is a complex of 550 units in South Delhi. Which is a low-rise, high-density scheme that combines the diversity in the units with axial pedestrian networks for a range of spatial and visual experiences. Also, that is based on the Self-Financing Scheme (SFS) for the Delhi Development Authority (DDA). Since the 1970s, there was an increasing need to cater to the housing of the citizens in Delhi. Also in Delhi, with the increasing strength of the professional and the trading classes in the cities along with migration from two and three-tier cities, housing strategies had to be considered for the needs of the middle-class group.

The Mass Housing Project

The Sheikh Sarai Housing is located in the Sheikh Sarai neighbourhood in New Delhi. And the site is about 35 acres. So the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) commissioned the architect Raj Rewal to design a residential housing scheme for the middle and lower-income group of people. Raj Rewal experimented with the Sheikh Sarai Housing Complex as one of the earliest experiment on the topic of social housing applied to a big scale site. It fits into an environment defined by the absence of symbolic features that characterize the site, which is located on the outskirts of New Delhi.

Construction of Units

The housing complex’s development began in 1978 and was completed in 1982. Subsequently, the Sheikh Sarai site was originally intended for the development of a combination of LIG, MIG, and HIG housing units. However, due to financial constraints, the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) introduced a new category of housing known as the Self-Financing Scheme (SFS). Within this scheme, the allottees had to pay for their units in 5 installments over the period of the construction of the units. As a result, people who signed up for a unit were entered into a lottery and had the option of specifying their preferences for unit type, layout, and location. The entire mass housing scheme is completely economically viable because of the subsidized housing units and also because of the use of local materials for construction. Finally, this increased the affordability of the apartments.

For the sake of completing the project, the housing units were classified into types. The break-up of the units was as follows –

- Category 1 – 48 units (1 Bedroom).

- Category 2 – 557 units (2 and 3 Bedrooms) and MIG – 192 units (3 Bedrooms).

Categories 1 and 2 were under the Self-Financing Scheme (SFS). Raj Rewal was the architect of the units in Sector D only, which consisted of the Category 2 units only.

Design Concept

Taking inspiration and connection with the historical cities like Udaipur and Jaisalmer in Rajasthan. Also, the Sheikh Sarai Housing is the characteristic of the urban fabric of India. And the design plans establish a clear concept of the close relationship between public and private spaces. As a result, the design arranges the open spaces in a methodical hierarchy throughout.

The mass housing clearly is based on the Haveli Typology inculcating the traditional patterns of urban space. On the other hand, these patterns are refined and perfected into ideal ensembles of collective dwellings. Raj Rewal has masterfully taken advantage of the irregularities on the site as every element offers a harmonious physical entity for living and working.

Urban Fabric

Built form of sheikh sarai housing by raj rewal, new delhi.

To imitate a traditional urban settlement, low-rise high-density walk-up flats are packed to form interior shaded streets linked by gateways and open courtyards (traditional Indian architectural components) for public use, and as an expression of style of the architect. The gateways, a common feature throughout the project, enabled a high level of transparency despite the fact that it was a high-density development, making it legible for the users.

Movement and Flow

Clear demarcation of vehicular and pedestrian streets, limiting vehicular flow to the road’s periphery with few access points along the road It improves pedestrian flow by puncturing the built solids along the central spine. So that is defined as the parking spaces and flow of traffic outside of the housing clusters. Moreover, there is a clear pattern connecting the movement to space, from person to neighborhood, also pedestrian to vehicular. The movement zones flow from the outer margins to the inner areas of the housing scheme, overlapping accordingly to create access points along the periphery.

Community Spaces at Sheikh Sarai Housing by Raj Rewal, New Delhi

Moreover creating intimate courtyards connected to one another, embodying traditional components of Indian architecture, to foster common areas for the community. The scale of these courtyards manipulates to encourage more social activities and interaction among the resident community, in addition to acting as social facilitators. So the individual to community equation structures through a progression of private spaces to squares of various sizes with shaded paths running throughout. Because every open space is meticulously controlled and organized, there is no room for neglected green spaces. Thus, the open greens are at the strategic places because they facilitate the orientation for the pedestrians.

Clusters and Units

The massing of building blocks creates clusters with inner courts and inside shaded streets. Also, the blocks of units connected. On the other hand, maintain the proper spacing between them and creates a system of covered pedestrian streets and internal courts. The organization of the blocks at Sheikh Sarai housing are also similar to the traditional medieval cities of Rajasthan.

Six different types of units ranging from 70-120 Sq.m. (70 Sq.m., 95 Sq.m., 110 Sq.m. and 120 Sq.m.), organized in two different clusters, 3 and 4 story high. The units come in a variety of sizes and types, ranging from studios to three-bedroom apartments. While the differences are slight, the necessity for economy and design is evident throughout the interior. Consequently, the apartments are tight, with no ambiguity of space caused by larger floor spaces to negotiate from. Despite the closeness and clustering of both units, each room is well-ventilated and well-lit, with an adjoining patio for each apartment. However, all the units are provided with courtyards or rooftop terraces.

Areas of Spaces of Sheikh Sarai Housing by Raj Rewal, New Delhi

- Area of Intervention – 38195 Sq.m. ~ 3.82 Ha.

- Built Up – 12740 Sq.m. ~ 1.2 Ha.

- Surface Parking – 6622 Sq.m. ~ 0.66 Ha.

- Green Areas – 3931 Sq.m. ~ 0.39 Ha.

Urban-scape at the site level, the architect developed the project by employing urban strategies of articulated flows, segregated spaces and applied the same on the site level. Therefore in a structured urban settlement. Raj Rewal designed the layout density at Sheikh Sarai as 100 DU/ha which comprised about 11% greater than the master plan applications. For instance, the compact dense development both on the ground floor and above maximized the use of space.

In conclusion, the Sheikh Sarai Project resembles the morphology of medieval Indian cities and its white composition, intentionally modern, is reminiscent of Udaipur. Most importantly, the housing scheme stands as yet another landmark in Delhi housing chronology and is responsible for the DDA’s middle-income housing to reach the limelight once again.

Also read: The Interlace in Singapore by Ole Scheeren

Brian Brace Taylor, M. P. (1992). Sheikh Sarai Housing – New Delhi . Retrieved from Raj Rewal Associates: https://rajrewal.in/portfolio/sheikh-sarai-housing-new-delhi/

Gupta, S. (June, 1991). Housing with Authority : The role of public and private architects in public housing in Delhi. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Kit, S. (2018, November 6). Research Project – Low-Cost Housing Issues (Solution) . Retrieved from Blogspot.com: https://samkit-education.blogspot.com/2018/11/research-project-low-cost-housing.html

SiddhikaChichani. (March 26, 2018). POST INDEPENDENCE ARCHITECTURE IN INDIASHEIKH SARAI HOUSING COMPLEX, NEW DELHI. Slideshare.net.

Singh, H. (August 12, 2015). SHEIKH SARAI HOUSING COMPLEX. Slideshare.net.

Don’t miss the latest case study!

We don’t spam! Read our privacy policy for more info.

You’ve been successfully subscribed to our newsletter!

Share this:

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Telegram (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Discover more from archEstudy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Type your email…

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Udaan: low-cost housing project by sameep padora and associates, aranya low-cost housing by bv doshi.

[…] Also Read: Sheikh Sarai Housing by Raj Rewal, New Delhi […]

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Most viewed posts, the history of chinese civilization.

- archEstudy Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

raj rewal asiad village housing

Related Papers

Katarzyna Kapusta

One could hardly imagine a time more exciting for an Indian architect to start a career than at the close of the 1940s, when India had just gained freedom from colonial rule. In many places around the world this was the time when enormous funds were invested in new and often very novel urban developments that were to provide, for better or worse, the model of metropolitan life for the generations to come. By that time, it was generally believed that architecture and urban planning have the power to shape human habits and inspire worldviews. This was also true for India, and at this particular moment it was crucial for decision makers and for the designers to decide on what style and what planning philosophy should they stake. What should the background image of the new Republic of India be, what values should be put through, what goals should be proclaimed? In my presentation, I am going to focus on these decisive years of modern architecture in India and on its major figures.

L Architecture D Aujourd Hui Aa

Pierre Frey

IDC international journal

pankaj chhabra

Sarbjit Bahga

Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret: The Indian Architecture Authors: Sarbjit Bahga and Surinder Bahga The book, though a modest addition to the voluminous publications, mostly descriptive, on these legendry architects, hope to throw light on some features hitherto not dealt with in earlier existing literature. The present book discusses almost all the works of Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret in India including some lesser-known ones as well as some projects which were not realized. Indeed some of these have been written about for the first time. In Particular Pierre Jeanneret’s works which were not so well-known earlier but find a befitting coverage in this book. Published after more than six decades of Chandigarh’s inception, this work portrays the up-to-date scenario of the built-environment vis-à-vis the inhabitants’ views on it. The reaction of the ultimate recipients of any delivery system, naturally based on their felt needs, is a most critical aspect for any in-depth analysis.

Ar. Asif Rizowan

In this paper we address the role of architectural criticism in the conception and practice of modernism in India – since post-independence till the present. India has witnessed a vast difference in the culture of the built environment. And as Modern Style of architecture arose from enormous transformations in the west during the late 19th, and flourished to India, Architectural Criticism says, it’s about time, that a new style of architecture, a style that describes the ‘Indianness’, originates, takes over, describes, and flourishes to bring a new face to the context of Architecture in India.

Dr. Shaji K. Panicker

Between the mid-1980s and late-1990s, an unprecedented tide of new publications on contem-porary architects and architecture in India appeared in print. These included several mono-graphs as well as more comprehensive surveys, exhibition catalogues, and a new “journal” of In-dian architecture, Architecture + Design (A+D) launched in 1984. Using Bourdieuean tools of analysis, this paper examines these architectural discourses about Indian architecture as a “field of restricted production” to better understand the context and dynamics of the conspicuous ur-gency to publish Indian architects and their work at that particular time. In so doing, the paper highlights inherent problems with the representation and historiography of ‘postcolonial’ archi-tecture in the context of the hegemonic discourses of modernity and its ‘postmodern’ critiques.

IAEME PUBLICATION

IAEME Publication

Generally, architecture can be termed as a field of art in building, a structure designed by human beings. Therefore, the grandeur and the height of a civilization is measured by the buildings it left behind which include religious buildings. This can be seen through Indian architecture that appeared as a result of the emergence of Buddhism and Hinduism. Between the main objectives of this study is to discuss the concept, goals and philosophy found in the architecture of India. In addition, the study also discusses the characteristics and elements of Indian architecture made up of Buddhist and Hindu architecture that has influenced some of the architecture of other buildings in the world. In this writing, the authors used qualitative methodology focusing on research on the analysis of documents and observations. The finding shows that the concept and philosophy of Indian architecture has been largely influenced by nation and world civilization. The study also identified the characters and elements. system along the western coast of India.

Thakur Manoj Singh

Indian architecture isone of the most famous in the world. Its architecture was based on the concept of religious plurality. One might notice that the architecture of Hindu, Buddhist, Islamic and colonial or Indo-saracenic were distinct. Based on these styles four historical eraswere classified i.e., the ancient Indian, pre-Islamic, and colonial periods. This article seeks to reassess the general perception of Indian Architecture and its relation to the formation of Indian identities. It focusses in particular on the interpretation of the concept of plurality n the academic world by western art-historians. The socioeconomic factorsplays determining role in defining the architectural styles of south Asia.

National Conference: Cultural Identities - Manifestation through Architecture (CIMA) 2020

Priyanka Gayen

Modern architectural heritage has various tangible & intangible values associated with them. It is the cultural significance of and the association of these values, which makes it heritage. Like ancient architectural heritage, the post-independence architecture of India has a potential association of values of cultural transformation, social & technological development, innovation, tradition & lifestyle. This paper attempts to explore the various values of the post-independence architecture of India, which makes it an integral part of the nation's cultural heritage. The period under consideration is five decades after independence (1947 to 2000)for this research. Cultural significance of the architecture of this period has been explored through the history of modern architecture of India and the significant modern architecture in the broader setting. For a comprehensive understanding of the cultural significance from a global perspective, there is a brief discussion of the values considered by major organisations involved in the recognition & protection of 20th-century heritage. In light of the broader spectrum of values associated with the architecture of this period and the cultural significance of the post-independence architecture of India, the values associated with the significant modern public buildings of this period have been identified.

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

SHODHKOSH : Journal and visual performimg arts

Dr GAURAV GANGWAR

Kiran S A T Y A B O D H Kalamdani

Paarija Saxena

IRJET Journal

Vandana Baweja

Proceedings of DARCH 2021- 1st International Conference on Architecture & Design

Neha Thunga

Peter Scriver

Ajinkya S Umbarkar

Oxford Bibliographies in Architecture, Planning and Preservation (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021)

Pushkar Sohoni

Daniele Vadalà

Ahmad Jawad NIAZI

Samia Gallouzi

Rajiv Mandal

Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand Conference 2012

Prajakta Sane

Syed Ali Nadeem Rezavi

Art of the Orient

Anna Rynkowska-Sachse

Subhankar Nag

International Journal for Research in Applied Science & Engineering Technology

IJRASET Publication

Shaymaa Esmail

Indo Nordic Author's collective

Dr. Uday Dokras

internation conference- sources of architecturl forms: theory and practice, Kuwait

Deepika Shetty

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Incremental Housing at Belapur: Exceptional Examples of Housing Designs in India

Incremental Housing at Belapur – Housing Design in India

In the ever-evolving landscape of Indian architecture, Incremental Housing at Belapur emerges as a trailblazer in redefining affordable living. This article explores the nuanced details of this exceptional housing design, delving into its innovative features and design principles that have transformed it into a beacon of progressive urban development.

Architectural Brilliance at Belapur

Pioneering affordable housing solutions.

Incremental Housing at Belapur stands as a pioneer in providing affordable housing solutions in the dynamic urban environment of India. Located in Belapur, Navi Mumbai, this architectural marvel challenges the traditional notions of housing design, offering a scalable and adaptable model for urban living.

Adaptive Design Philosophy

The design philosophy behind Incremental Housing revolves around adaptability. Architects envisioned a structure that could evolve alongside the changing needs of its residents, allowing for incremental growth and ensuring that the housing complex remains relevant and functional over time.

Innovative Spatial Planning for Flexibility

Scalable living spaces.

One of the standout features of Incremental Housing is its scalable living spaces. The design allows for gradual expansion, enabling residents to start with a basic structure and incrementally add additional rooms or features as their needs and family size grow. This approach ensures that the housing remains accessible to a broad demographic.

Modular Construction Techniques

Modular construction techniques play a pivotal role in the spatial planning of Incremental Housing. The use of prefabricated and modular components allows for efficient construction, reducing costs and providing a framework for residents to customize their living spaces as per their requirements.

Community-Centric Living

Shared amenities and open spaces.

Incremental Housing fosters a sense of community through shared amenities and open spaces. Common areas, playgrounds, and recreational zones are strategically integrated into the design, encouraging residents to interact and create a vibrant community within the housing complex.

Community Participation in Design

The design of Incremental Housing emphasizes community participation. Residents have a say in the development and evolution of the housing complex, creating a collaborative environment where the community actively contributes to shaping its living spaces.

Sustainable Practices and Environmental Sensitivity

Green building materials and energy efficiency.

Environmental sustainability is a core focus of Incremental Housing. The use of green building materials, energy-efficient systems, and sustainable construction practices align with global efforts towards eco-friendly urban development.

Rainwater Harvesting and Waste Management

To minimize the environmental impact, Incremental Housing incorporates rainwater harvesting systems and efficient waste management practices. These initiatives contribute to resource conservation and create a more sustainable living environment.

Technological Integration for Modern Comfort

Smart infrastructure and connectivity.

While prioritizing affordability, Incremental Housing does not compromise on modern comforts. The housing complex integrates smart infrastructure, providing residents with connectivity solutions, efficient energy management, and digital services that enhance the overall quality of life.

Digital Inclusion for Residents

The design also focuses on digital inclusion, ensuring that residents have access to technology that can improve their daily lives. From digital communication platforms to online community services, Incremental Housing embraces technology as a tool for empowerment and convenience.

Architectural Aesthetics and Cultural Integration

Adaptive façade and aesthetic appeal.

The adaptive façade of Incremental Housing adds to its aesthetic appeal. Architects have carefully designed the exterior to be visually pleasing while allowing for modifications and expansions. This adaptability ensures that the housing complex maintains a cohesive and attractive appearance.

Integration with Local Culture and Context

Incremental Housing seamlessly integrates with the local culture and context of Belapur. The architectural elements draw inspiration from the surrounding environment, creating a housing complex that feels rooted in its cultural context while embracing modern design principles.

Challenges and Adaptive Solutions

Urban planning constraints.

Navigating urban planning constraints posed challenges during the development of Incremental Housing. Architects collaborated with local authorities to find adaptive solutions that met regulatory requirements while staying true to the vision of creating affordable and scalable living spaces.

Infrastructure and Connectivity Challenges

Addressing infrastructure and connectivity challenges required innovative solutions. Incremental Housing incorporates infrastructure improvements, such as efficient transport links and enhanced connectivity, to overcome initial challenges and create a well-integrated community.

Impact on Urban Development and Future Prospects

Model for affordable housing initiatives.

Incremental Housing at Belapur serves as a model for affordable housing initiatives across India. Its success demonstrates that affordable living and architectural innovation can coexist, setting a precedent for future urban development projects aimed at addressing the housing needs of diverse populations.

Potential for Replication in Urban Centers

The scalable and adaptable nature of Incremental Housing makes it a potential solution for replication in various urban centers. The housing model can be customized to suit the unique challenges and opportunities presented by different cities, offering a flexible approach to urban development.

Rethinking The Future (RTF) is a Global Platform for Architecture and Design. RTF through more than 100 countries around the world provides an interactive platform of highest standard acknowledging the projects among creative and influential industry professionals.

Lee Ha Jun: Architectural Alchemy in Set Design Mastery

Es Devlin: Transforming Spaces into Theatrical Canvases

Related posts.

Wingsweep: A Masterpiece by Kendrick Bangs Kellogg

Fernandez Architecture: Crafting Elegance and Minimalism in Architectural Excellence

Christ Hospital Joint and Spine Center, USA: Revolutionizing Healthcare Architecture

Buerger Center for Advanced Pediatric Care, USA: Elevating Pediatric Healthcare Architecture

The New Hospital Tower at Rush University Medical Center, USA: Redefining Healthcare Architecture Excellence

Teletón Infant Oncology Clinic, Mexico: A Paradigm of Healing Architecture

- Architectural Community

- Architectural Facts

- RTF Architectural Reviews

- Architectural styles

- City and Architecture

- Fun & Architecture

- History of Architecture

- Design Studio Portfolios

- Designing for typologies

- RTF Design Inspiration

- Architecture News

- Career Advice

- Case Studies

- Construction & Materials

- Covid and Architecture

- Interior Design

- Know Your Architects

- Landscape Architecture

- Materials & Construction

- Product Design

- RTF Fresh Perspectives

- Sustainable Architecture

- Top Architects

- Travel and Architecture

- Rethinking The Future Awards 2022

- RTF Awards 2021 | Results

- GADA 2021 | Results

- RTF Awards 2020 | Results

- ACD Awards 2020 | Results

- GADA 2019 | Results

- ACD Awards 2018 | Results

- GADA 2018 | Results

- RTF Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2017 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2016 | Results

- RTF Sustainability Awards 2015 | Results

- RTF Awards 2014 | Results

- RTF Architectural Visualization Competition 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2020 – Results

- Designer’s Days of Quarantine Contest – Results

- Urban Sketching Competition May 2020 – Results

- RTF Essay Writing Competition April 2020 – Results

- Architectural Photography Competition 2019 – Finalists

- The Ultimate Thesis Guide

- Introduction to Landscape Architecture

- Perfect Guide to Architecting Your Career

- How to Design Architecture Portfolio

- How to Design Streets

- Introduction to Urban Design

- Introduction to Product Design

- Complete Guide to Dissertation Writing

- Introduction to Skyscraper Design

- Educational

- Hospitality

- Institutional

- Office Buildings

- Public Building

- Residential

- Sports & Recreation

- Temporary Structure

- Commercial Interior Design

- Corporate Interior Design

- Healthcare Interior Design

- Hospitality Interior Design

- Residential Interior Design

- Sustainability

- Transportation

- Urban Design

- Host your Course with RTF

- Architectural Writing Training Programme | WFH

- Editorial Internship | In-office

- Graphic Design Internship

- Research Internship | WFH

- Research Internship | New Delhi

- RTF | About RTF

- Submit Your Story

Institutional

Exhibitions

Sheikh Sarai Housing - New Delhi

Year : 1970-1982

Location : New Delhi

Project Details

The Sheikh Sarai Housing, a complex of 550 units in South Delhi, is a low-rise, high density scheme that combines diversity in units with axial pedestrian networks for a range of spatial and visual experiences and is based on self-financing scheme for Delhi Development Authority.

The design evolved from a specific area based programme for the Lower Income Group (LIG) and Middle Income Group (MIG) detailed by the DDA. With peripheral parking, the plan strings together a series of variable housing types with pedestrian squares, streets and pathways.

The design is based on clear pattern: connecting movement to space, from person to neighbourhood and pedestrian to vehicular. The individual-to-community equation was structured through a progression of private spaces to squares of varying sizes with shaded paths running throughout. The vehicular to pedestrian zones flow from the outer margins to the inner areas of the scheme, overlapping accordingly to create access points along the periphery. All the units have been provided with courtyards or roof top terraces.

“The mass housing that Rewal built at Sheikh Sarai based on the haveli typology and traditional patterns of urban space has been refined, purified and perfected into ideal ensembles of collective dwellings. Masterfully taking advantage of the irregularities of the site, the Laboratories and the dwellings, with walkways, courtyards and terraces offer a harmonious physical entity for living and working.”

Brian Brace Taylor

Monograph on Raj Rewal 1992 by Mimar Publications

View Gallery

Advertisement

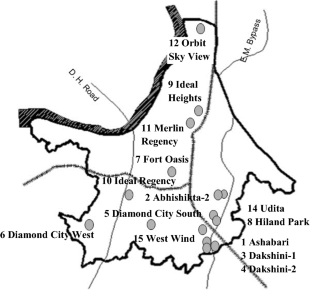

Interactional spaces of a high-rise group housing complex and social cohesion of its residents: case study from Kolkata, India

- Published: 12 March 2021

- Volume 36 , pages 781–820, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Soumi Muhuri ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1224-936X 1 &

- Sanghamitra Basu 2

1129 Accesses

8 Citations

Explore all metrics

A Correction to this article was published on 28 April 2021

This article has been updated

From concerns of mental health problems and behavioural issues of residents of high-rises, this research tries to explore the association of interactional spaces (the spaces of interaction in a high-rise housing) with dimensions of social cohesion (the social relations) of the residents. Presuming social cohesion is an important determinant of their mental health. To have both the researchers’ and users’ perspectives while an investigation, this research incorporates perception of the residents, analysis of layout plan, behaviour observation and space syntax analysis. Later, with the help of hierarchical linear regression model it identifies the significant attributes and uses of interactional spaces (both at outdoor and indoor) that facilitate or inhibit social cohesion. The finding indicates that the arrangement and use of the streets and tot-lots within a housing complex have a significant contribution in strengthening social cohesion of the residents. Further, more than actual use, the opportunities of a chance encounter and opportunities of use of the spaces appear to be more effective. The findings of the research would have a wider application not only in high-rise group housing but other instances as well.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Common space as a tool for social sustainability

Socio-spatial structure of urban communities and the distribution of crime in Makurdi, Nigeria

Research on Co-housing Model—Experience and Applicability to Housing Design for Low-Income People in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

Change history, 28 april 2021.

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-021-09842-z

It encompasses the terms of high-rise (ten-storeyed or more than ten storied high building), group housing and residential complex. Group housing is ‘Housing for more than one dwelling unit, where land is owned jointly….and the construction is undertaken by one Agency’ (National Building Code of India, 2016, part 3, p.11). A residential complex means a building or buildings with more than twelve residential units (place of residence in the form of house or apartment) with a common area and one or more facilities or services within “a premises” (p.17); the entire layout is approved by any legal authority but not intended for personal use of an individual (Ministry of Finance, Government of India, 2016).

Abu-Ghazzeh, T. M. (1999). Housinglayout, social interaction, and the place. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 19, 41–73.

Google Scholar

Aggarwal, M. (2001). Outdoor Play Areas for Children in High-Density Housing in Montreal . Master of Architecture Dissertation. Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research, School of Architecture, McGill University, Montreal.

Al-Kodmany, K. (2018). The sustainability of tall building developments: A conceptual framework. Buildings, 8 (7), 1–31.

Barros, P., Ng Fat, L., Garcia, L. M. T., Slovic, A. D., Thomopoulos, N., de Sá, T. H., Morais, P., & Mindell, J. S. (2019). Social consequences and mental health outcomes of living in high-rise residential buildings and the influence of planning, urban design and architectural decisions: A systematic review. Cities, 93, 263–272.

Batty, M. (2001). Exploring isovist fields: space and shape in architectural and urban morphology. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 28, 123–150.

Benedikt, M. L. (1979). To take hold of space: isovists and isovist fields. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 6, 47–65.

Can, I., & Heath, T. (2016). In-between spaces and social interaction: a morphological analysis of Izmir using space syntax. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 31, 31–49.

Carmona, M., Tiesdell, S., Heath, T. & Oc T. (2010). Public Places Urban Spaces : The Dimensions of Urban Design. (Elsevier).

Chatterjee, M. (2018). A study on loneliness and social interaction pattern among the high rise dwellers of Kolkata city. The Research Journal of Social Sciences, 9, 26–32.

Chattopadhyay, S. (2000). Residential Satisfaction in Public Housing-A study. PhD Dissertation, Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur.

Chen, D. (2006). Shared outdoor spaces and community life: Assessing the relationship between design and social interaction . Master of Landscape Architecture Dissertation, Faculty of Graduate Studies, University of Guelph.

Clark, D. L. C. (2007). Viewing the Liturgy: A space syntax study of changing visibility and accessibility in the development of the Byzantine Church in Jordan. World Archaeology, 39 (1), 84–104.

Dave, S. (2011). Neighbourhood density and social sustainability in cities of developing countries. Sustainable Development, 19, 189–205.

Dawson, C. T., Wu, W., Fennie, K. P., Ibanez, G., Cano, M. A., Pettit, J. W., & Trepka, M. J. (2019). Perceived neighborhood social cohesion moderates the relationship between neighborhood structural disadvantage and adolescent depressive symptoms. Health and Place, 56, 88–98.

Dempsey, N. (2009). Are good-quality environments socially cohesive?: Measuring quality and cohesion in urban neighbourhoods. Town Planning Review, 80 (3), 315–345.

Domènech-Abella, J., Mundó, J., Haro, J. M., & Rubio-Valera, M. (2019). Anxiety, depression, loneliness and social network in the elderly: Longitudinal associations from the Irish longitudinal study on ageing (TILDA). Journal of Affective Disorders , 246 , 82–88.

Evans, G. W., Wells, N. M., & Moch, A. (2003). Housing and mental health: A review of the evidence and a methodological and conceptual critique. Journal of Social Issues, 59 (3), 475–500.

Ewing, R., & Handy, S. (2009). Measuring the unmeasurable: Urban design qualities related to walkability. Journal of Urban Design, 14 (1), 65–84.

Fisher, K. D. (2009). Placing social interaction: An integrative approach to analyzing past built environments. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 28, 439–457.

Fone, D., Dunstan, F., Lloyd, K., Williams, G., & Watkins, J., & Palmer, S. (2007). Does social cohesion modify the association between area income deprivation and mental health? A multilevel analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology, 36, 338–345.

Franz, G., & Wiener, J. M. (2008). From space syntax to space semantics: a behaviorally and perceptually oriented methodology for the efficient description of the geometry and topology of environments. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 35, 574–592.

Gehl, J. (2011). Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space . Island Press.

Gifford, R. (2007). The consequences of living in high-rise buildings. Architectural Science Review, 50, 1–16.

Ginsberg, Y., & Churchman, A. (1985). The pattern and meaning of neighbor relations in high-rise housing in Israel. Human Ecology, 13, 467–484.

Grange, A. L. (2011). Neighbourhood and class: A study of three neighbourhoods in Hong Kong. Urban Studies, 46, 1181–1200.

Ha, S. (2010). Housing, social capital and community development in Seoul. Cities, 27, S35–S42.

Hall, E. T. (1966). The Hidden Dimension . Doubleday.

Hillier, B. (2005). The art of place and the science of space. World Architecture , 185, Beijing, Special Issue on Space Syntax, pp 96–102.

Hillier, B., & Hanson, J. (1984). The Social Logic of Space . Cambridge University Press.

Ho, D. C., Chau, K., Cheung, A. K., Yau, Y., Wong, S., Leunga, H., Laub, S. S., & Wong, W. (2008). A survey of the health and safety conditions of apartment buildings in Hong Kong. Building and Environment, 43, 764–775.

Hochschild Jr., T. R. (2011). Neighbors by Design: Determinants and Effects of Residential Social Cohesion . PhD Dissertation, University of Connecticut.

Hoogland, C. (2000). Semi-private Zones as a Facilitator of Social Cohesion . Nijmegen University.

Huang, S. L. (2006). A study of outdoor interactional spaces in high-rise housing. Landscape and Urban Planning, 78, 193–204.

Karuppannan, S., & Sivam, A. (2011). Social sustainability and neighbourhood design: an investigation of residents’ satisfaction in Delhi. Local Environment, 16 (9), 849–870.

Keane, C. (1991). Socioenvironmental determinants of community formation. Environment and Behavior., 23 (1), 27–46.

Kearns, A., Whitley, E., Mason, P., & Bond, L. (2012). ‘Living the high life’? Residential, social and psychosocial outcomes for high-rise occupants in a deprived context. Housing Studies, 27, 97–126.

Kim, J. Y., & Kim, Y. O. (2020). The association of spatial configuration with social network for elderly in social housing. Indoor and Built Environment, 29 (3), 405–416.

Koo, Terry K., & Mae, Y. Li. (2016). A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine , 15 (2), 155–163.

Kuo, F. E., Sullivan, W. C., Coley, R. L., & Brunson, L. (1998). Fertile ground for community: Inner-city neighborhood common spaces. American Journal of Community Psychology, 26 (6), 823–851.

Kweon, B., Sullivan, W. C., & Wiley, A. R. (1998). Green common spaces and the social integration of inner-city older adults. Environment and Behavior, 30 (6), 832–858.

Lee, J. (2011). Quality of life and semipublic spaces in high-rise mixed-use housing complexes in South Korea. Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, 10 (1), 149–156.

Lee, S. (2005). Spatial Order and Sense of Community in High-Rise Apartment Developments in Bundang, the Metropolitan area of Seoul, Korea . Master of Architecture Dissertation, The University of New South Wales Faculty of Built Environment.

Lee, Y., Kyoungyeon, K., & Lee, S. (2010). Study on building plan for enhancing the social health of public apartments. Building and Environment, 45, 1551–1564.

Lyman, S. M., & Scott, M. B. (1967). Territoriality: A neglected sociological dimension. Social Problems, 15, 236–249.

Mak, W. W. S., Cheung, R. Y. M., & Law, L. S. C. (2009). Sense of Community in Hong Kong: Relations with community-level characteristics and residents’ well-being. Americal Journal of Community Psychology, 44, 80–92.

Mousavinia, S. F., Pourdeihimi, S., & Madani, R. (2019). Housing layout, perceived density and social interactions in gated communities: Mediational role of territoriality. Sustainable Cities and Society, 51 (101699), 1–14.

Muhuri, S., & Basu, S. (2018). Developing residential social cohesion index for high-rise group housing complexes in India. Social Indicators Research , 137 (3), 923–947.

Nicoll, G. (2007). Spatial measures associated with stair use. American Journal of Health Promotion, 21 (4), 346–352.

Ong, B. L. (2003). Green plot ratio: an ecological measure for architecture and urban planning. Landscape and Urban Planning, 63, 197–211.

Osmond, P. (2011). The convex space as the 'Atom' of urban analysis. The Journal of Space Syntax, 2 (1), 97–114.

Park, G., & Evans, G. W. (2016). Environmental stressors, urban design and planning: implications for human behaviour and health. Journal of Urban Design, 21 (4), 453–470.

Peponis, J., Wineman, J., Rashid, M., Hong Kim, S., & Bafna, S. (1997). On the description of shape and spatial configuration inside buildings: convex partitions and their local properties. Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design, 24, 761–781.

Pomeroy, J. (2008). Sky courts as transitional space: Using Space syntax as predictive theory . Conference Proceedings, CTBUH 8th World Congress, 1–8.

Reddy, K. N. (1996). Urban Redevelopment: A Study of High-Rise Buildings . Concept Publishing Company.

Ridwana, R., Prayitno, B., & Hatmoko, A. U. (2018). The relationship between spatial configuration and social interaction in high-rise flats: A case study on the Jatinegara Barat in Jakarta. SHS Web of Conferences, 41, 1–7.

Shim, J., Park, S. & Park, E. (2004). Public Space Planning of Mixed-use High-rise Buildings—Focusing on the Use and Impact of Deck Structure in an Urban Development in Seoul . Conference Proceedings, Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, Seoul, Korea, pp 764–771.

Skjaeveland, O., & Garling, T. (1997). Effects of interactional space on neighbouring. Journal of Environmental Psychology , 17 (3), 181–198.

Skjaeveland, O., Gilding, T., & Maeland, J. G. (1996). A multidimensional measure of neighboring. American Journal of Community Psychology, 24, 413–435.

Talen, E. (2016). Sense of community and neighbourhood form: An assessment of the social doctrine of new urbanism. Urban Studies , 36 (8), 1361–1379.

Turner, A. (2004). Depthmap 4- A Researcher’s Handbook (electronic version) . Bartlett School of Graduate Studies.

Turner, A., & Penn, A. (1999). Making isovists syntactic: isovist integration analysis . (Paper presented in the 2nd International Symposium on Space Syntax, Universidad de Brasilia, Brazil)

Urzua, C. B., Ruiz, M. A., Pajak, A., Kozela, M., Kubinova, R., Malyutina, S., Peasey, A., Pikhart, H., Marmot, M., & Bobak, M. (2019). The prospective relationship between social cohesion and depressive symptoms among older adults from Central and Eastern Europe. Journal of Epidemiol Community Health, 73, 117–122. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2018-211063

Article Google Scholar

Yau, Y. (2010). Sense of community and homeowner participation in housing management: A study of Hong Kong. Urbani izziv, 21, 126–135.

Zhang, W., & Lawson, G. (2009). Meeting and greeting: Activities in public outdoor spaces outside high-density urban residential communities. Urban Design International, 14 (4), 207–214.

Zhang, W., Liu, S., Zhang, K., & Wu, B. (2019). Neighborhood Social Cohesion, Resilience, and Psychological Well-Being Among Chinese Older Adults in Hawai’i. Gerontologist , pp 1–10.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Kharagpur for providing us with the necessary support and facilities for the research that was funded by the Ministry of Human Resource and Development (MHRD), India.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Planning and Architecture, National Institute of Technology, Rourkela, Odisha, 769008, India

Soumi Muhuri

Department of Architecture and Regional Planning, Indian Institute of Technology, Kharagpur, West Bengal, 721302, India

Sanghamitra Basu

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Soumi Muhuri .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: The heading of the Table 1 was incorrectly published as “Sense of belonging to a group (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.889, composite reliability = 0.890)”. However, it is intended only for the first nine entries. The correct heading of the table 1 is "Dimensions/Subdimensions”.

Appendix A: Details of characteristics of residents

Characteristics of respondents | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

Mother tongue | ||

Bengali | 469 | 71.9 |

Other | 183 | 28.1 |

Age | ||

18–24 | 6 | 0.9 |

25–29 | 23 | 3.5 |

30–34 | 51 | 7.8 |

35–39 | 98 | 15.0 |

40–44 | 78 | 12.0 |

45–49 | 84 | 12.9 |

50–54 | 78 | 12.0 |

55–59 | 72 | 11.0 |

60–64 | 70 | 10.7 |

65 and more | 92 | 14.1 |

Gender | ||

Female | 261 | 40 |

Male | 391 | 60 |

Marital status | ||

Single | 18 | 2.8 |

Married | 602 | 92.3 |

Widowed/widower | 29 | 4.4 |

Separated | 3 | 0.5 |

Education | ||

10th standard (school level education) | 3 | 0.5 |

12th standard (school level education with a specialisation) | 15 | 2.3 |

Diploma/certificate | 5 | 0.8 |

Graduate | 137 | 21.0 |

Post graduate | 187 | 28.7 |

Professional | 280 | 42.9 |

PhD | 25 | 3.9 |

Occupation | ||

Student | 8 | 1.2 |

Home maker | 176 | 27.0 |

Retired | 129 | 19.8 |

Service | 245 | 37.6 |

Self-employed | 54 | 8.3 |

Business | 40 | 6.1 |

Total | 652 | 100.0 |

Characteristics of households | Number | Percentage | Mean (Median) | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Household size | 3.22 (3) | 1.29 | 1 | 11 | ||

Number of Earning member | 1.41 (1) | 0.61 | 0 | 4 | ||

Average income of an earning member | ||||||

Rs.10000/- to Rs.14999/- | 1 | 0.2 | ||||

Rs.15000/- to Rs.24999/- | 17 | 2.6 | ||||

Rs.25000/- to Rs.49999/- | 151 | 23.2 | ||||

above Rs.50000/- | 483 | 74.1 | ||||

Children ≤ 12 years | ||||||

Absence | 464 | 71.2 | ||||

Presence | 188 | 28.8 | ||||

Present apartment type | ||||||

2Bedroom | 202 | 31.0 | ||||

3Bedroom | 410 | 62.9 | ||||

≥ 4Bedroom | 40 | 6.1 | ||||

Super built up area | ||||||

up to 1000 | 119 | 18.3 | ||||

1100–1500 | 401 | 61.5 | ||||

1600–2000 | 100 | 15.3 | ||||

2000 + | 32 | 4.9 | ||||

Present tenure type | ||||||

Rented | 53 | 8.1 | ||||

Owned | 599 | 91.9 | ||||

Duration of stay | ||||||

< 1 year | 36 | 5.5 | ||||

1–4 years | 343 | 52.6 | ||||

5–10 years | 262 | 40.2 | ||||

> 10 years | 11 | 1.7 | ||||

Past location | ||||||

Outside the country | 11 | 1.7 | ||||

Outside the state but same country | 92 | 14.1 | ||||

Outside the city but same state | 113 | 17.3 | ||||

Same city | 436 | 66.9 | ||||

Past type of residence | ||||||

Other | 18 | 2.8 | ||||

Independent house | 238 | 36.5 | ||||

5 storey apartment | 312 | 47.9 | ||||

More than 5 storey apartment | 84 | 12.9 | ||||

Past tenure type | ||||||

Other | 44 | 6.7 | ||||

Rented | 174 | 26.7 | ||||

Owned | 434 | 66.6 | ||||

Total | 652 | 100.0 | ||||

Appendix B: Details of attributes of the physical environment

Objective attributes of contextual environment | Valid cases | Percentage | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Development types | ||||||

Government | 4 | 26.67 | ||||

Private | 8 | 53.33 | ||||

Joint venture | 3 | 20.00 | ||||

Site area (acre) | 15 | 0.74 | 18.40 | 6.11 | 4.65 | |

Total dwelling units | 15 | 95.00 | 1000.00 | 430.00 | 285.07 | |

Maximum building height | ||||||

< 20 storeyed | 11 | 73.33 | ||||

20 storeyed and more | 4 | 26.67 | ||||

Housing layout typology | ||||||

Molecular | 2 | 13.33 | ||||

Linear | 4 | 26.67 | ||||

Courtyard | 6 | 40.00 | ||||

Linear cum courtyard | 3 | 20.00 | ||||

Dwelling units/hectare | 15 | 89.00 | 317.00 | 200.60 | 68.63 | |

Dwelling units/50 m length of street | 15 | 19.00 | 41.00 | 28.07 | 6.79 | |

Dwelling units/building | 15 | 30.00 | 154.00 | 68.80 | 36.81 | |

Dwelling units/floor lobby and corridor | 15 | 3.00 | 8.00 | 5.40 | 1.40 | |

Dwelling units/entrance door | 15 | 19.00 | 77.00 | 42.87 | 15.69 | |

Average number of floors per building | 15 | 8.00 | 23.00 | 13.73 | 4.60 | |

Ground coverage (%) | 15 | 15.00 | 41.00 | 27.20 | 8.46 | |

Location of dwellings | ||||||

Up to 5th floor | 256 | 39.26 | ||||

6–10th floor | 231 | 35.43 | ||||

11–15th floor | 113 | 17.33 | ||||

16–20th floor | 37 | 5.67 | ||||

21–25th floor | 15 | 2.30 | ||||

Provision of park–playground–common terrace | ||||||

Presence | 11 | 73.33 | ||||

Absence | 4 | 26.67 | ||||

Provision of tot-lot | ||||||

Presence | 13 | 86.67 | ||||

Absence | 2 | 13.33 | ||||

Facilities in housing complex | ||||||

Basic | 6 | 40.00 | ||||

Abundant | 9 | 60.00 | ||||

| ||||||

Adjacent building height | 15 | 10.00 | 24.00 | 14.00 | 3.87 | |

Active frontage (%) | 15 | 20.00 | 50.00 | 35.20 | 7.76 | |

Bench or inbuilt seating along street | ||||||

Presence | 5 | 33.33 | ||||

Absence | 10 | 66.67 | ||||

Extent of greenery along the street (weightage) | 15 | 0.00 | 10.00 | 7.33 | 3.46 | |

| ||||||

Total area (square meter) | 13 | 103.9 | 1436.00 | 581.78 | 407.59 | |

Area/DU | 13 | 0.4 | 6.4 | 1.59 | 1.71 | |

Convexity | 13 | 0.41 | 1.00 | 0.67 | 0.21 | |

Adjacent building height | 13 | 0.00 | 23.00 | 11.85 | 6.50 | |

Active frontage (%) | 13 | 3.00 | 100.00 | 36.31 | 26.44 | |

Bench or inbuilt seating | ||||||

Absence | 7 | 53.85 | ||||

Presence | 6 | 46.15 | ||||

Trees/flower/shrub/grass in tot-lot | ||||||

Presence | 11 | 84.62 | ||||

Absence | 2 | 15.38 | ||||

Mound | ||||||

Presence | 2 | 15.38 | ||||

Absence | 11 | 84.62 | ||||

| ||||||

Total area (square meter) | 11 | 883.30 | 13,200.00 | 5333.25 | 4209.77 | |

Area/DU | 11 | 3.40 | 20.90 | 10.71 | 5.59 | |

Convexity of park | 11 | 0.32 | 0.7700 | 0.5555 | 0.15 | |

Adjacent building height (storey) | 11 | 10.00 | 24.00 | 14.55 | 4.20 | |

Active frontage | 11 | 13.00 | 41.00 | 23.27 | 9.53 | |

Visual focus in park | 11 | |||||

Presence | 10 | 90.90 | ||||

Absence | 1 | 9.09 | ||||

| ||||||

Total area (square meter) | 15 | 4.70 | 13.1 | 8.07 | 2.17 | |

Area/DU | 15 | 46.80 | 680.48 | 46.80 | 197.01 | |

Active frontage (%) | 15 | 6.00 | 16.00 | 11.73 | 2.52 | |

View towards outdoor | 15 | |||||

Presence | 9 | 60.00 | ||||

Absence | 6 | 40.00 | ||||

| ||||||

Total area (square meter) | 52.60 | 9059 | 917.69 | 2264.13 | ||

Area/DU | 0.30 | 1.30 | 0.77 | 0.28 | ||

| ||||||

Seating area | 15 | |||||

Presence | 3 | 20.00 | ||||

Absence | 12 | 80.00 | ||||

View towards outdoor | 15 | |||||

Presence | 8 | 53.33 | ||||

Absence | 7 | 46.67 |

Visibility and accessibility | Street | Tot-lot | Park-playground-common terrace | Floor lobby and corridor | Ground floor lobby |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

Connectivity | 4.20 (1.12) | 7.06 (4.23) | 4.68 (1.17) | 2.87 (0.77) | 2.80 (0.56) |

Global integration(Rn) | 1.08 (0.25) | 1.36 (0.56) | 1.20 (0.25) | 1.52 (0.76) | 1.52 (0.53) |

Local integration (R3) | 1.72 (0.28) | 2.11 (0.57) | 1.88 (0.27) | - | - |

Control | 1.72 (0.52) | 3.14 (1.67) | 1.87 (0.51) | 2.45 (0.87) | 2.09 (0.86) |

Controllability | 0.34 (0.05) | 0.39 (0.08) | 0.32 (0.09) | 0.60 (0.23) | 0.54 (0.20) |

Spaciousness | 5374.39 (4283.90) | 5934.81 (4784.21) | 7392.57 (4319.68) | 44.20 (14.64) | 43.73 (14.32) |

Openness | 90.23 (31.63) | 79.02 (30.49) | 94.77 (35.40) | 87.74 (41.31) | 70.47 (28.09) |

Complexity | 0.0132 (0.00) | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | 0.02 (0.01) |

Occlusivity | 352.08 (243.15) | 338.55 (247.00) | 443.00 (241.46) | 23.78 (14.37) | 20.87 (9.39) |

Compactness | 0.17 (0.06) | 0.1938 (0.08) | 0.16 (0.08) | 0.17 (0.08) | 0.21 (0.07) |

Perceived attributes | Valid cases | Minimum | Maximum | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|

(Values based on group mean) | ||||

Convenience of use of interactional spaces | 15 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

Visual appearance | 15 | 3.06 | 4.73 | 4.00 |

Comfortable microclimatic condition or protection from sun and wind | 15 | 3.25 | 4.88 | 4.00 |

Safety and security of children | 15 | 3.58 | 4.79 | 4.00 |

Opportunity of passive contact with nature | 15 | 3.67 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

Quietness | 15 | 3.61 | 4.75 | 4.00 |

Maintenance and management | 15 | 3.34 | 4.64 | 4.00 |