| Author: | Jeffrey G. Barlow | | Title: | Globalism and Changes to the Internet: Editorial Essay | | Publication info: | Ann Arbor, MI: MPublishing, University of Michigan Library

May 2002 | | Rights/Permissions: | | | Source: |

Jeffrey G. Barlow

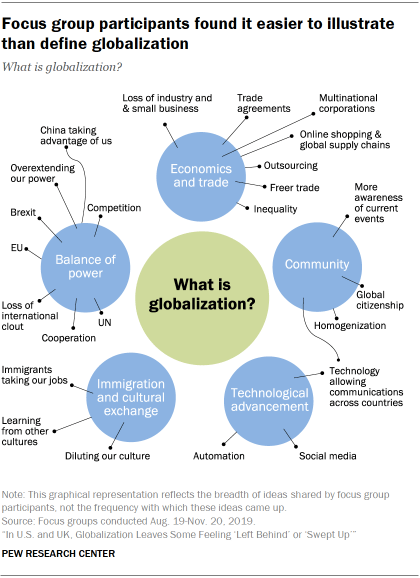

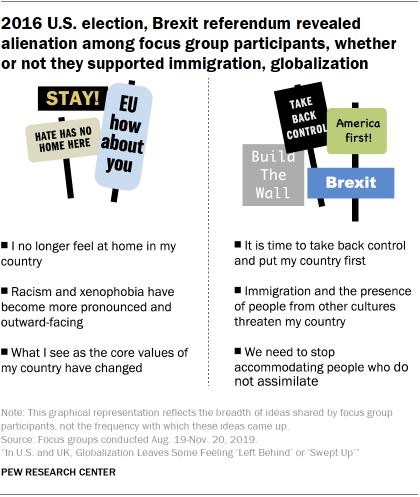

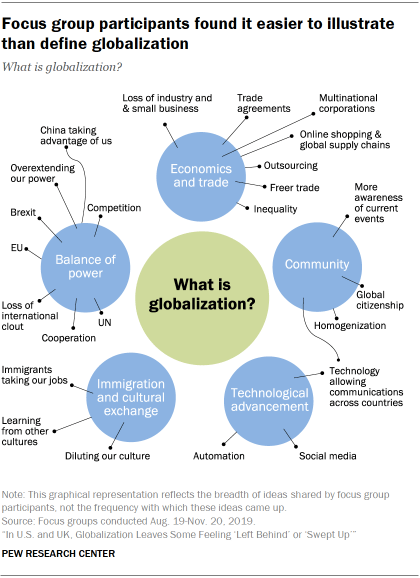

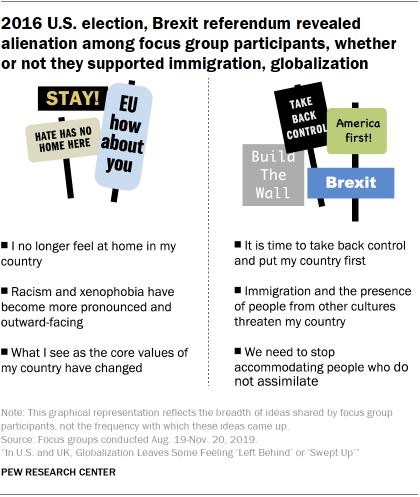

vol. 5, no. 1, May 2002 | | Article Type: | Editorial | | URL: | http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.3310410.0005.105 | Globalism and Changes to the Internet: Editorial Essayby Jeffrey Barlow [email protected] Editor, Journal of the Association for History and Computing. .01. IntroductionAs we begin our fifth year of publishing the JAHC we find ourselves in a period of great change. When we first began planning for this journal, in the Fall of 1997, the Internet was clearly a very promising mode of scholarly communication, but little more than that. Our first editorial in June of 1998, was entitled " Why an Electronic Journal in History?" —we felt we had to justify our decision to enter this new medium. After careful consideration, we decided that the more our publication looked like a conventional hard-copy scholarly journal, the less we would trigger scholarly anxieties about publishing electronically. Accordingly, we decided against taking advantage of many of the developments in hypertext, producing rather what now looks like a rather quaint museum piece that might well be labelled "Early Scholarly Publishing on the Internet" in some electronic archive. In the four years since we began, both the Internet and the Journal have proven very successful. We have had the pleasure of blazing a trail for many, and often have been consulted, both in the United States and in Europe, on how best to begin an electronic journal in other fields. Our founding group of scholars is now the American Association for History and Computing, and was admited as an affiliate to the American Historical Association in faster time than any previous group in the AHA's long history. We have had the pleasure of publishing a number of noted scholars and often have seen their articles reprinted in paper journals. Our members are very busy with public presentations and workshops. Several who began as electronic neophytes are now heading up centers for studying or publishing electronic materials. We are in discussions with a major academic publisher for a hard-copy series on electronic materials in history, following upon several successful years of producing M.E. Sharpe's History Highway series. These are all, of course, gratifying achievements, made possible by a very hard working group of scholars, both national and international. But above all, we were simply at the right place at the right time, at the beginning of the transition from hard copy publishing to electronic publishing just as the field began to take off. Those first four years were a period of what now seems to be almost complete anarchy; there were few rules and almost no precedents, beyond trying to live up to the traditional concerns of our predecessor historians. It seems a strange question, but more than once we asked ourselves what Thucydides or Ssu-ma Ch'ien would have done with this new medium. We now find ourselves at the brink of a new era, at a period of consolidation as we begin to consider not only the advantages of the Internet, but also some of the disadvantages. Those of us we have played joyfully in the fields of anarchy now must ask ourselves where it is that we are going. Accordingly, this editorial attempts to consider the Internet and the place of the JAHC within a very broad historical perspective. Here we consider the linked topics of the Internet, globalism, global civic culture, scholarship, and terrorism. At first glance these topics may seem so disparate as to be unrelated. But we argue below that they are closely related and are of major importance in the future development of the Internet. We begin with globalism and global civic culture, consider terrorism, and end by asking what price we are willing to pay for security as it effects scholars and their use of the Internet. In brief, we argue here that the Internet and globalism are closely related in their development; they are key factors in defining the era in which we live. Although globalism is primarily an economic process, it includes cultural processes that are creating a global civic culture, and the Journal of the Association of History and Computing is one part of that culture. But economic globalism does not require the Internet in its present form, and there are reasons to believe that changes are inevitable. The Internet has also seriously eroded the power of the state, including the American one; terrorism is one aspect of that loss of power. We think that the institution of the state is now responding to that challenge and that It is possible, indeed, probable, that we will have economic globalism, but not cultural globalism, in at least the short run. We think the Internet of the immediate future will be very different than that of the past four years, and that electronic journals like the JAHC, and scholars in general will face a significant challenge in adapting to those changes. This is a long and complex arguement and we promise not to burden our readership with such more than once every five years. We begin by discussing globalism. .02. Defining GlobalismWhen we speak of globalism, we most often refer to its economic aspects. But globalism also embraces many cultural issues. Because its impact is so extensive and so deeply felt, a precise definition of the concept is elusive. [1] Jon Katz, the very active editorial writer at Slashdot.com ("News for Nerds —Stuff that Matters"), writes [2] : I've been writing about it [globalism] for years, and got more than 2,000 responses and e-mails about it from some columns here last week, but you know what? I still couldn't tell you exactly what it is. "It's the biggest evil facing the world," e-mailed JDRow. "It's the only hope the world really has," messaged a professor from Amherst. Neither could say what it was. Can you? Given the lack of a standard definition of this term, we attempt one here, intended to fit our own uses of the term below: Globalism is the spread of a very wide range of ideas and practices, principally economic ones, beyond the boundaries of individual nations into the world arena. The most controversial impacts have tended to be economic ones because, while many Americans are concerned about the potentially adverse economic consequences of globalism on their jobs or lives, few worry about the impact of American culture abroad. At the JAHC, we have observed that impact and perhaps have contributed to it as well. [3] .03. Globalism and the InternetIt is apparent that the Internet itself is directly related to the phenomenon of globalism or globalization if we wish to view it as the dynamic process that it is, rather than as a static entity. The Internet is a cause of globalization in that it is perhaps the single most important communications channel by which values and practices are spreading beyond individual nation states. It enables international businesses to exchange vast electronic files and powerful graphical images. Scholars have been able to assemble communities of discourse around topics that earlier were considered too "small" in light of the difficulties presented by print publication within an international context. At the JAHC our "World Languages" editorial board often puts the abstract of our articles into a wide variety of languages such as French, German, Spanish, Italian, Russian, and Japanese. More than ten percent of our readers access us from non-English speaking nations. As dramatic as these changes have been, far greater ones are taking shape. Within the foreseeable future bandwidth or carrying capacity will be sufficiently large to make the downloading of Hollywood films a practical means of accessing far larger audiences in a far more timely and cost-effective fashion than is presently true. Non-governmental entities and individuals will be able to participate in multipoint video conferencing, as do well-funded business groups today. In the somewhat more distant but still forseeable future, the combination of wireless and satellite transmissions will open up the most remote household to the world, providing, of course, that the potential consumer can somehow afford these marvels. The contemporary era, sometimes referred to as "post-industrialism", also has been called the "Age of Informationalism" [4] by Manuel Castells, Berkeley sociologist and the author of the encyclopedic multi-volume work, The Information Age: Economy, Society, and Culture . Castells is probably, internationally at least, if not in the United States, the most influential analyst working in the field. He emphasizes that the phenomenon of informationalism differs from earlier stages of industrialization. The feedback loop between process (the digital production of a wide variety of artifacts, but principally, information) and product (information) is much more important and the loop closes much faster than in industrial processes. New processes lead to new information, which almost immediately leads to new processes, ad infinitum. [5] The Internet is clearly the critical link in the dissemination of this information as well as being in considerable part the market for it, if we consider the Internet to be the entire system of digital communication, from desktop processors where the information is created to the browsers of end users. But the Internet is also in part a result of globalization. The spread of markets and production processes abroad has included with it the production and consumption of the vast array of computer technology necessary to the Internet at every step, from the creation of an HTML file, to the applications and mechanisms necessary to send and receive it over the equally necessary cables and wires that embody the "net". .04. Globalism and Earlier Expansions of TradeA wide variety of responses to globalism have emerged, all the way from dismissive comments that it is, in fact, merely the same old struggle for markets that has consumed mankind's energies from the beginnings of trade, to impassioned arguments that globalism is an entirely new phenomenon with epochal reach and consequences. [6] It is comforting to many (and politically necessary to others) to believe that globalism is merely an evolution of earlier economic processes. Both the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, two of the institutions leading economic globalization, are officially committed to this view. [7] I think, however, that this view is far more convenient than it is accurate. There is a great difference between the British East India Company, perhaps the most important British mercantilist corporation and the leader in expanding trade in the early modern age, and such firms as today's Nike, Inc. The critical factor in the Informational age is that processes, ownership, and management practices are all networked. Nike, although here in Oregon we like to think of it as a local firm, is not even an American firm in any important sense. The British East India Co., though distributed worldwide, was British. It had an important relationship with the British state, its owners were British, and the ships' bottoms it leased were British owned. Nike is a worldwide network whose "campus" could as easily be in Vancouver B.C., as in Beaverton, Oregon. Moreover, It does not itself produce anything, save perhaps for fashion designs. Its production processes are themselves networked; only a very few shoe parts are made directly by Nike. It employs subcontractors to produce shoes abroad that are then mostly sold through outlets owned by others, though Nike perhaps owns a few stores outright. Its production processes are "just-in-time" and dependent upon electronic communications for their cost effectiveness. To believe that Nike is merely following in the wake of the British East India Co. as a capitalist enterprise is to miss very important differences between the two entities, and between the two eras in which they exist. Important shifts in underlying values have also, not surprisingly, occurred. .05. Positive Responses to GlobalismMany scholars have observed that there has been within the American value system of the last several decades, a conflation of what were earlier quite distinct ideas. "Freedom" now means, to many Americans the freedom to make consumer choices. This idea is a very powerful one that has raised an abstract notion of "market" to such a height that Harvey Cox, a noted theologian, has observed that the market now performs many of the functions earlier ascribed to "God." [8] Given the widespread public repetition endlessly hammered home by all forms of media that freedom is primarily economic freedom, it is not surprising that Americans see the spread of consumer choices via globalization as an unmixed blessing. Moreover, it is clear that in many cases access to the global market on any terms whatsoever is a sine qua non to breaking the fetters of traditional economies. [9] However much activists criticize international firms such as Nike for their practices in overseas production, it is also true that jobs producing in and for the global market are a welcome alternative to traditional poverty for many workers in countries such as Indonesia or Vietnam; they also are often the only alternative. .06. Negative Responses to GlobalismAmericans usually see globalism as an international phenomenon. But because of the sheer economic strength of the United States, much of the world views it as a type of American expansionism. [10] Benjamin Barber argues that it is this aggressive pursuit of a global market society that has precipitated the anger of much of the Muslim world, and made them vulnerable to true terrorists. [11] Even United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan, who is clearly committed to an open world economic order, warned business leaders at the World Economic Forum which met in New York in early February, 2002: The reality is that power and wealth in this world are very very unequally shared, and that far too many people are condemned to lives of extreme poverty and degradation"230;The perception, among many, is that this is the fault of globalization, and that globalization is driven by a global elite, composed of, at least represented by, the people who attend this gathering. [12] .07. The Emergence of a Global Civic CultureThere are many consequences of globalization but we wish to focus upon an unintended result of economic processes directly related to the Internet: the emergence of a shared body of humanistic values that shows us the outlines of a true global civic culture. These values could, in effect, if they continued to coalesce, one day be characteristic of a sort of world citizenship. It is not surprising that there is a relationship between informationalism and culture; what is the content of informationalism if not culture? As Castells states, "technology [13] And neither is it surprising that there is a feedback between processes and content; indeed, as Castells reminds us, this is perhaps the primary characteristic of this current stage of production, whether we call it post-industrialism or informationalism. To cite an aspect of global culture that is particularly pertinent to the JAHC: In dealing with historical articles that come in from abroad, we have always chosen to enforce "traditional" (i.e., Western European and American) standards for evidence and citation upon them. In other cultures, such as the former Soviet Union, China, and Japan, the citation of evidence has often been more related to professional status hierarchies than to "proof" in the Euro-American sense. By doing so, we spread those standards among young professional elites in those cultures and in doing so unwittingly undermine those status hierarchies. There are many and far broader indications of the recent emergence of global systems of values. One such is the number of contemporary socio-political movements that have risen locally and then quickly become global. The most striking recent phenomenon is probably the Zapatista movement of Chiapas, Mexico, or the protracted series of World Trade Organization (WTO) protests. [14] But others would include the anti-landmine movement, many feminist campaigns dealing with the lot of third world women, concerns about child labor, sexual exploitation, consumers' rights, protection of the rights of indigenous peoples, or those of religious minorities such as Tibetan Buddhists and Fa Lun Gong practitioners in the Peoples' Republic of China, to name but a few of many possible examples. While some of these may seem to many to be purely political and lacking a broad base, they are above all united by a shared ethic. These ethical systems define appropriate behaviors between workers and employers, between sovereign states and their citizens, between businesses and consumers, and between human beings and the earth itself. [15] While these movements are certainly at important levels separate ones, when taken together they increasingly constitute an international and unified movement, usually called "human rights". There are, however, important differences between local human rights movements, and the human rights movement when viewed in a global context. In illuminating this distinction, I find it useful to refer here to personal experience. I am, by academic training, a historian of modern China. I have lived in Chinese cultures, in either Taiwan or Guilin in south China, close to the Vietnam border, for more than six years, funded by two Fulbright grants and generous support from other sources. I have also studied or taught in Hue, Vietnam, on many occasions for a period of a month or so. In the more than thirty years that I have been moving between Taiwan, China, Vietnam, and the United States, I have seen many political and economic changes. Taiwan was a rather grim one-party dictatorship upon my first visit in 1967. It is now a vibrant multiparty democracy. Guilin, China, was almost indescribably poverty-stricken in 1975. Now large sections of it are equivalent to Hong Kong in consumer appeal. Vietnam is perhaps at the beginning of such a period of rapid progress. When the human rights movement began to focus upon China, beginning in the 1970's, it seemed to me that the criticism, while often well-founded, was, in fact, largely politically motivated. It was very much in the interest of the United States in particular to constantly remind the world that China was a spectacular failure in human terms, regardless of the leaps and bounds it was taking in political and recently, in economic, strength and influence. The Chinese argument, which I to some degree accept, was that even the United States has its weaknesses in terms of human rights. Above all, we tend to ignore economic rights, often refusing to join international conventions on human rights because we wish to avoid accepting standards measured against which even our wealthy society does not appear entirely successful. The Chinese still see human rights arguments as politically motivated attempts at "political interference" in their internal affairs. As well, they argue that "cultural differences" usually explain these misunderstandings of their internal practices. As long as the human rights movement had a predominantly American cast, the Chinese were in some important part correct. But the Internet has broadened the movement. Now idealists or co-religionists all over the world concern themselves with the fate of Tibetan Buddhists, with Chinese student activists, or more oddly, with the Fa Lung Gong, to many a rather traditional Chinese messianic sectarian movement to which have been added the modern attributes of a pyramid scheme. Chinese arguments no longer protect them, in my mind at least, because the human rights movement is an international network and does not hesitate to criticize the United States as well. For example, a Google search on "Abu Jamal," the imprisoned Philadelphia journalist and activist, will turn up thousands of pages, many in French, German, or other non-English languages. Even Amnesty International, long the bane of the Chinese, called for a new trial for him. [16] However much as an American I might sometimes resent foreign misunderstandings of the workings of my society, I recognize that the Chinese and other states (including my own) now have to meet increasingly higher standards in the treatment of their citizens. There are no longer any purely "internal affairs". Neither are "cultural differences" a justifiable defense of violations when these are measured not against parochial and often politically motivated national standards, but against emerging global ones. The impact of these many global movements, and the distinction between today's human rights movements and earlier ones, depends above all upon their shared or networked nature. The Zapatista movement in and of itself was a minor Mexican peasant insurgency. But when news of the events in Chiapas were disseminated world-wide, principally via the Internet, a wide variety of pressures were bought to bear to circumscribe the range of actions open to the Mexican government in suppressing the movement. [17] The same became true for the American government that had long resisted the proscribing of the use of landmines by international agreements. [18] And while Abu Jamal did not get the new trial called for by Amnesty International, he was granted a hearing that freed him from the death penalty. [19] But while these movements might all be seen as broadly humanistic ones, depending on how we feel about their political values, there are, of course, many others which are offensive by most standards. We have argued elsewhere that the terrorist network known as Al Quaeda grew up in the Informationalist environment and depends upon it. So, too, do such organizations as those of holocaust deniers and criminal groups such as international drug cartels. [20] Each of these entities, like globalism itself, has the effect of reducing the sovereignty of nation states, an issue covered in detail below. Because the United States is clearly the dominant player in the process of globalization as currently constituted, and because these processes are so much to the advantage of politically influential world economic elites, Americans pay little attention to the diminishment of sovereignty, save on the extreme left and the extreme right where paranoids, muttering darkly about various conspiracies, meet. When Americans are concerned about a loss of sovereignty, these concerns often are assuaged by the tenets of "market fundamentalism" in that it is widely accepted that the less government interferes in consumer choice ("freedom") the more freedom we all have. But the developing global civic culture does not have equivalently powerful defenders. .08. Who Speaks for the Internet?To argue that the Internet is not as well defended as the market system is not to say that it is totally undefended. Free speech advocates, for example, are quick to speak out for the Internet. [21] Many businesses, too, have a considerable and growing stake in the Internet, though we believe that their support is highly contingent; the Internet could well be changed significantly and still meet business needs. But the Internet also has many detractors. We need only to glance at the list of offensive groups listed above to remind ourselves of some of the shortcomings of a totally open Internet environment. We favor freedom of speech, but we are not so sure about pornographers, holocaust deniers, and much less sure about terrorists having access to this high digital road. The Internet has another weakness in that it produces losers just as it produces winners. As it changes the communications environment, it not only brings new businesses and new practices into being, in many cases it destroys old ones. [22] Among the groups that are truly concerned about the Internet, of course, are state governments who see their tax incomes steadily eroded as commerce moves online. But surely the greatest sin of the Internet is to diminish the power of sovereign nation states. When governments become aware that non-state players are successfully using the Internet, whether to restrict the ability of the Chinese state to arrest religious dissidents, to spread the word that Catholic priests have been arrested in Vietnam, or that jihadists have facilitated catastrophic attacks utilizing digital resources, many concerned with security begin to wonder if some restrictions are not necessary. The Chinese government monitors incoming international traffic; the Vietnamese government makes public access to the Internet very difficult by closely controlling Internet Service Providers and in effect licenses end-users one by one. Europeans have recently passed a major new law with radical implications for the Internet. [23] And the United States has passed the USA Patriot Act. [24] The hopes of many for the development of the Internet as a tool for democratization, including open scholarly communication, have been very high. [25] But these hopes are necessarily dependant upon the continued open nature of the Internet. It is obvious that there is a direct relationship between the process of globalization and the development and spread of the Internet. But these two processes serve quite different groups and there is no reason to believe that the connection must necessarily be maintained indefinitely. It would be quite tempting in many regards for specific groups to facilitate the former while restricting the latter. This would have disastrous consequences for the development of global civic culture. We believe that this process is inevitable and is well underway. These changes will flow from the impact of the Internet upon the power of the nation state, including most especially the American one. .09. The Power of the StateWe have argued elsewhere that the events of September 11, 2001, can be understood to a considerable degree as the result of the impact of the Internet. [26] We believe that in a larger sense the root causes of the phenomenon of terrorism is a relative dimunition of the power of the nation state vis-a-vis nonstate poltical actors, as a result of the development of networked organizations made possible by the Internet. In preparing this argument, we have found very useful a recent work, Joseph S. Nye Jr's The Paradox of American Power . [27] Nye is a considerable figure, even in the talented ranks of American scholar-bureaucrats, ranks that include such figures as George Kennan and Henry Kissinger. Nye is a former Chairman of the National Intelligence Council, and was Assistant Secretary of Defense in the Clinton administration. He is currently Dean of Harvard University's Kennedy School of Government. He has written a number of influential works in addition to this latest one [28] Nye's analysis of globalization and of the origins and consequences of the Internet, though considered from the primary focal point of U.S. policy rather than from the focal point of the impact of the Internet itself, roughly agrees with our foregoing analysis. Where Nye adds considerable value, however, is in spelling out the impact of the Internet upon American power. .10. "Hard Power"Nye is, of course, as a former Assistant Secretary of Defense, well acquainted with what he terms "hard power", i.e., the traditional elements of state power such as military force and economic influence. He states that: "Military power and economic power are both examples of hard command power that can be used to induce others to change their position." [29] In short, "hard power" flows largely from economic and military strength and is at least implicitly coercive. .11. "Soft" PowerBut Nye goes on to define an additional type of power, "soft power": A country may obtain the outcomes it wants in world politics because other countries want to follow it, admiring its values, emulating its example, aspiring to its level of prosperity and openness. In this sense it is just as important to set the agenda in world politics and attract others as it is to force them to change through the threat or use of military or economic weapons. This aspect of power—getting others to want what you want—I call soft power. [30] American hard power is different from that of the country in previous eras, or from that of previous great powers only in degree: recent conflicts such as Desert Storm, the war in Kosovo or the Afghani campaign show an unparalleled blend of fire power and technological sophistication, an ability to so dominate the "battle space" as to make war appear almost effortless, as well as largely bloodless, at least for American forces. .12. The Origins of Soft PowerHowever, American soft power, Nye argues, is quantitatively and qualitatively different from earlier American power, or from that of previous great powers. American values and institutions are being projected world wide, largely as a consequence of the related phenomenon of globalization and what Nye terms "the global information age." [31] As we argued earlier, neither of these can be disentangled from the growth of the Internet itself. While soft power greatly benefits the United States in that it tends to make others emulate Americans, and thus to want what they want, it is not, unlike military power, a deliberate consequence of policy. Rather, soft power flows from a number of extra-governmental sources such as popular culture, from scholarly groups like the American Historical Assocation, from the exemplary power of legal and political institutions, from U.S.-based human rights groups, even from groups such as the anti-W.T.O. protestors, who, even while attacking the system, disseminate widely held American values. Nye refers to this process as "social globalization," and also sees an "incipient... civil society at the global level." [32] This corresponds to what we earlier termed "Global Civic Culture." Much of Nye's analysis is intended to make a relatively simple point: The United States is indefinitely unchallengeable in terms of its "hard power"; but "soft power" is growing steadily more important in a networked world, and is the more frangible of American sources of power. There will be a natural evolution that somewhat vitiates the impact of American soft power in any event as other information economies mature. For example, by 2010, Nye argues, there will be more Chinese Internet users than American ones. [33] While American sites will remain very attractive, because of the fact that English has become the world's second language, China too sits at the center of a linguistic empire that not only embraces the worldwide Diaspora of Chinese people, but also in the past embraced much of East Asia including Korea, Japan, Vietnam, and other nations. .13. A Dichotomy or a Transition?Nye's position intersects at several points with the analysis of Manuel Castells, [34] Nye's argument follows in time upon that of Castells in that Castells wrote in 1996, Nye after September 11, 2001. But Nye's position is ultimately grounded in an earlier tradition of "realist" definitions of power: Power used to be in the hands of princes, oligarchies, and ruling elites; it was defined as the capacity to impose one's will on others. Modifying their behavior. This image of power does not fit with our reality any longer [35] ... Castells spends far more time than does Nye considering the "Information Age." In doing so, he perhaps has the advantage in contextualizing American power. His argument is also far more dynamic. To Castells, the Information Age is an ongoing process, which he considers from a number of perspectives. But Nye believes that there are two dichotomous kinds of power: "hard" and "soft", and the relationship between them is a static one. For Castells, there are not two kinds of power, but a still incomplete transition from one kind of power to another. For Castells, power is being permanently transformed; Nye's "hard" power is eroding: states, even the most powerful one, the United States, now live in an environment marked by a decentralized net of "local terror equilibria." [36] In the past, during the Cold War, several major states and their allies established an equilibrium based upon mutual assured destruction; this prevented any one power from dominating the global political or economic system, but it also protected each of the major states from the others. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union the United States then enjoyed a brief period of near absolute dominance. .14. American Power Following 9-11But global processes had already distributed a variety of weapons of mass destruction among major and minor powers, and more importantly, among non-state actors as well. September 11, 2001, revealed the vulnerabilities of even the greatest of powers to non-state actors. The devastating effect of the low-cost and relatively simple improvised weapons that were used then suddenly illuminated a terrible new world. The use of a bacteriological weapon, Anthrax, then followed quickly upon the trauma of 9-11—so quickly that historians may well treat the two events as one. This attack revealed an additional and, to many, even more terrifying vulnerability and again showed the new power of non-state actors. Castells refers to these sorts of weapons, including chemical and biological ones, as well as the feared low-yield "dirty" nuclear devices sometimes referred to as "suitcase bombs" as "veto technologies" and presumes that this new decentralized web of great and small states and non-state actors will require constant small interventions by many different powers to maintain a relative peace. This seems to be an apt description of events since September 11 as a variety of alliances, states, and international organizations have joined the campaign against terrorism. There are, then, many indications that Castells is, to a considerable degree at least, correct in his analysis of state power in the Information Age, and Nye wrong. State power is evolving toward a decentralized fabric, like all else in the Information Age. .15. The Limitations of the Networked International SystemThere are also many indications that some in the American policy-making institutions understand the implications of a world like that described by Castells. Recently (March, 2002), the Pentagon report "The Nuclear Posture Review" discussed conditions under which the United States might use nuclear weapons. This analysis immediately attracted a great deal of attention because it suggested the first-strike employment of nuclear weapons against non-nuclear powers. Since the end of World War II such use has been presumed to be outside the parameters of civilized warfare, and particularly outside American nuclear doctrine. But times have changed. As stated by one reporter, Michael Gordon, "Another theme in the report is the possible use of nuclear weapons to destroy enemy stocks of biological weapons, chemical arms and other arms of mass destruction." [37] These are, of course, precisely the "veto technologies" listed by Castells. [38] The limitation in the current international system is probably most critically, from an American point of view, that it tends to restrain unilateral American action. As a result, great attention necessarily must be paid to alliances and coalition building. But if anything terrifies the international community it is the specter of nuclear war, or the possibility of a return to a Cold War system with its attendant enormous expenses and the inherent threat of destruction. .16. The Nuclear Posture ReviewThe "Nuclear Posture Review" represents the Bush administration's attempt to break the bonds that presently restrains American power: first-strike use of nuclear weapons effectively removes the need to consult allies. It amounts to an attempt to restore the brief period of absolute domination (and absolute security) enjoyed by the U.S. following the fall of the Soviet Union, before we had become aware of the terrible new forces that could be employed by "rogue states" and criminal organizations such as Al Quaeda. If the United States were to be successful in putting the terrorist genie back in the bottle by threatening nuclear strikes on states that both harbor terrorists and possess weapons of mass destruction, including most especially chemical and bacteriological ones, then Nye is, perhaps, correct: There are two sorts of power and the United States can continue to enjoy a near monopoly of classical "hard" power. But Nye, like Castells, recognizes that "under the influence of the information revolution and globalization, world politics is changing in a way that means Americans cannot achieve all of their international goals acting alone." [39] The uproar, both domestic and international over the implications of the "Nuclear Policy Review" is evidence of the essential accuracy of Castell's analysis9. [40] Once again, the United States has discovered the limits of state autonomy in a networked system. .17. Additional Causes of the Loss of State PowerIn Addition, Castells' broader analysis of the Information Age lets us see a number of other factors critical to state power. Castells demonstrates, we think, that the power of all states, including the American state, is being irreversibly eroded, not by enemies who can be confronted with nuclear weapons, but by historical processes, most especially by globalization and the development of the Internet. This is not to agree with the claims of some that the state is in any sense disappearing. The Libertarian dream of replacing the state by infallibly just and accurate market forces are simply that, a dream. But the role of the state, like all else, must yield before the impact of globalization and the development of the Internet. Exactly how it changes is not important to our analysis at this point; it is a topic to which we will return below. Above all, the state is losing power in the face of globalized economic processes facilitated by networked means of communication. Globalization has raised capital flows to the level of hazard earlier represented only by catastrophic forces of nature. Portuguese state power was destroyed by the earthquake at Lisbon in 1755, effectively ending the great era of Portuguese exploration and expansion. And Portugal was, of course, one of the first powerful states. But capital flows struck with far more devastating effect the economies of Korea, Thailand, Japan, and many other states in the late twentieth century. As long as states are dependant upon an interlocked world economy, no nation can long act independently. The economist Paul Krugman suggests the nature of this problem: Foreigners have been wildly enthusiastic about America for years – an attitude we have come to count on, because we need $1.2 billion in capital inflows every day to cover our foreign-trade deficit. What happens as they lose their enthusiasm? One of the largely unreported stories of the last few months – in the U.S. media, anyway – is the precipitous decline of foreign confidence in American leadership and institutions. Enron, aggressive accounting, budget deficits, steel tariffs, the farm bill, F.B.I. bungling – all of it adds up, in European minds in particular, to what Barton Biggs of Morgan Stanley calls a "fall from grace." Foreign purchases of U.S. stocks, foreign acquisitions of U.S. companies, are way off. [41] As long as the U.S., or any other state, is so dependent upon foreign investment, it dare not ignore the international climate of opinion. .18. The Link Between States and Their Citizens WeakensCastells raises additional relevant factors. He believes that the essential element of state influence in the 20th century has been its bottom-line welfare functions. When all else fails individual citizens, it has been the industrial state that has provided a social safety net. But globalization and the networking of production effectively cause states to continually reduce welfare expenses. In the struggle for markets, it is the system with the leanest cost structure that wins. There are now no remaining great power welfare states. This not only weakens individual ties to the state, but also causes many to perceive that it is the state itself, by entering into agreements such as The North American Free Trade Association (NAFTA) and the WTO, that is responsible for their plight. In an effort to regain citizen loyalty, many states, including those as disparate as the United States and the Peoples' Republic of China, have chosen to decentralize budgetary and control processes to ever lower administrative levels. Paradoxically, this further reduces the power of the state, and attenuates loyalty to it. Furthermore, this tendency is further enhanced by another characteristic of the Internet: the continual creation of micro-communities of interest that increasingly command the loyalty of individuals. Even internal political institutions are deeply affected by globalization and the Informational Society. The political party structures in each of the major states have been simultaneously weakening. This process is furthest advanced, of course, in the United States, where the Informational Society itself is the most advanced. There are probably many factors that contribute to this development, many of which are related to either globalization or the Internet. The increasing inability of the state to disburse welfare funds, for example, clearly weakens many local or state level political machines. But it is probably the Information Society itself that is primarily responsible. [42] Once again Castells coins an apt term with which to explain these events: "informational politics." [43] Simply put, electronic media have displaced print media as the space in which politics is discussed. This implies the same collapse of time and broadening of impact that characterizes electronic media in general. In addition, the contest for audience attention continually drives the media to seek broader and broader audiences with the resultant reluctance to deal with any issues, particularly controversial ones, in detail or over an extended period of time lest the audience move on to more diverting sources of infotainment. Because politics now exist largely in media space, appearance has become more important than substance. And as a result citizens defect from the political process as essentially irrelevant or corrupt. Another consequence of political action being conducted in media space is the development of a tendency to attribute complex events to colorful attention-grabbing individuals who can seize media attention. This means that a worldwide Islamicist reaction to globalization and the Internet is reduced to the single figure of Ibn Bin Laden. This process, of course, empowers charismatic and ultimately simplistic individuals who can reduce complex issues to quickly transmitted symbolic explanations. .19. How Might the State Respond?The problems of the American state in the Informational Age recently have been greatly ameliorated by the simple fact that the American people have come under attack. This has silenced critics of the state ranging from parties out of power to even local anti-state groups such as Citizen Militias. This problem is only temporarily solved, of course, by such expedients as mounting a war against external enemies. However, it may be that a war against terrorism that goes on indefinitely and continually expands will arrest the continuing decline of the state, perhaps also indefinitely. It may ultimately, however, also exacerbate the decline if state responses are eventually seen once again as costly, misguided, and counter-productive. [44] We have argued here that state responses that are not directed at the actual sources of individual problems risk being ineffective, or at best will not be both efficient and maximally effective. However, a state such as the United States is an extremely powerful organism and may well solve many of its problems simply by profligate expenditures of economic and military resources. But if the nature of such problems as the terrorist attack of September 11, 2001, and the diminishing claims of all states to citizen loyalty are indeed in some considerable part a consequence of those changes we encapsulate here as globalization and the networked society, then the attempts to ameliorate the results of these changes properly should be directed at the causes themselves. From the American perspective, many of the consequences of 9-11 can be summarized as problems of decreased security. We all experience our lives and our property as markedly less secure than they were on September 10, 2001. We are engaged in a passionate discussion concerning appropriate solutions. Few, if any, believe that we can restore the level of security we felt on the 10 th as opposed to the 11 th , and many of us probably agree that our previous feelings of security were, in any event, illusory. Here we conclude by asking a final question relating to the problems raised by globalization and the Internet: How much are we willing to pay for security? .20. Where Were We Before 9-11?The world has so changed since the events of 9-11 (at least for Americans) that we might well remind ourselves what that earlier context was like. To an historian, the period from the rapid popularization of the Internet to 9-11 may one day be labeled as the interim between the end of the Cold War and the beginning of the War Against Terrorism. For many, it may simply be characterized as a world without terrifying enemies and the threat of major wars. There were conflicts, and they had their costs, but not even Desert Storm defined the era in the same way as the Cold War and the War Against Terrorism have defined theirs. For most, however, this period was best defined by the development and rapid expansion of the Internet. Bill Gates, the dominant personality of this interim era, said of it: Today, the Internet is "230; the center of attention for businesses, governments and individuals around the world. It has spawned entirely new industries, transformed existing ones, and become a global cultural phenomenon. [44] .21. What problems did the Internet face before 9-11?However, even in what now seems to have been a more innocent era, there were security concerns directly related to the Internet. In 1998, F.B.I. Director Louis J. Freeh, in a report "Threats to U.S. National Security" before the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence on January 28, 1998, said: The overriding concern now facing law enforcement is how rapidly the threats from terrorists and criminals are changing, particularly in terms of technology, and the resulting challenge to law enforcement's ability to keep pace with those who wish to do harm to our nation and our nation's citizens. This is why the encryption issue is one of the most important issues confronting law enforcement and potentially has catastrophic implications for our ability to combat every threat to national security that I am about to address in my statement here today. [46] This threat might be summed up as the ability of terrorists and criminals to communicate without detection. Not only was the almost infinite number of the media channels and messages themselves an obstacle to detection (A recent estimate has it that 610 billion e-mail messages were sent in 2001.) [47] but even if detected, the messages could well prove to be unreadable due to strong encryption. In addition to simple encoding, the most well known of these techniques, steganography, was a means of opening up the digital code of a graphical image so as to insert an encoded message that did not itself appear in the image. These were very difficult to identify in the welter of electronic images on the World Wide Web, and even if detected, often impossible to decode. [48] The federal government, however, had a number of tools at its disposal. One of these was a system known as "Carnivore." Carnivore was: A computer-based system that is designed to allow the FBI, in cooperation with an Internet Service Provider (ISP), to comply with court orders requiring the collection of certain information about emails or other electronic communications to or from a specific user targeted in an investigation. [49] Carnivore provided law enforcement agencies with access to two functions characteristic of earlier wire-tapping in a POTS (Plain Old Telephone Service) electronic environment: "Trap-and-trace/pen-register" and "Content-wiretap." The former is simply tracing electronic traffic to and from a given client of an ISP (Internet Service Provider) and keeping a register of the origin and destination of all e-mail traffic. This served the function of demonstrating in a court of law that a given individual was in contact with other given individuals; for example, that a person suspected of mafia activity indeed had communicated with known Mafiosi as demonstrated by a pen-register. The latter, as suggested by the title, was a record of the content of messages. Both these functions, because evolutions of earlier operations in POTS environments, were well defined by law. [50] In the climate before 9-11 individual privacy rights were carefully protected so that the state was required to demonstrate compelling need to access private communications and to do so under carefully controlled and highly limited conditions. Any failure to follow the complicated legal requirements of placing a tap and keeping records resulted in the materials being inadmissible in a court, negating the whole purpose of the taps. One indication of the relative seriousness with which such taps were viewed in law was that it required the signature of a federal district court judge to place a Carnivore tap into an ISP. So high was the concern for privacy rights within electronic environments in the period preceding 9-11 that the FBI spent a great deal of time and energy simply in explaining the system. This extended even to making electronically available an extensive document, "Independent Technical Review of the Carnivore System". [51] This study, conducted openly by a consortium of major universities, permitted any concerned citizen to understand the nature of the technical system. So widespread was concern over Carnivore and its possible misuses in many communities that it inspired many thousands of explanatory and cautionary web sites. [52] One can conclude then, that not only was the public interest in privacy protected by law, but that a very large community of concerned citizens had access to basic information relating to the system and its capabilities, presumably reducing the threat of its abuse. A system about which far less was known, and one that was correspondingly more problematic for those concerned about privacy issues was "ECHELON." [53] The Federation of American Scientists provides the following summary of ECHELON. ECHELON is a term associated with a global network of computers that automatically search through millions of intercepted messages for pre-programmed keywords or fax, telex and e-mail addresses. Every word of every message in the frequencies and channels selected at a station is automatically searched. The processors in the network are known as the ECHELON Dictionaries. ECHELON connects all these computers and allows the individual stations to function as distributed elements (of) an integrated system. An ECHELON station's Dictionary contains not only its parent agency's chosen keywords, but also lists for each of the other four agencies in the UKUSA system"230; [54] Because of the lack of information on ECHELON it was possible to believe almost anything about it. The system was presumed to have been created and maintained by the National Security Administration (NSA), an agency assumed to have an unlimited budget and access to emerging technologies and the best scientific minds. The NSA, moreover, has been permitted by the U.S. Congress to keep most of its operations secret, as befitting a security agency. Concerns about ECHELON, however, tended to be more restricted than those about Carnivore, because it was presumed to be deployed abroad. Foreign nations did worry that it was used by the NSA to access proprietary commercial information that was then turned over to competing American businesses. [55] Some American civil liberties groups were concerned that oversight over its operations, whatever they were, was inadequate. These were then the concerns of citizens as related to the Internet and the state. Compared to the terrors of the Cold War, they were relatively minor. But from the government's point of view, there were still major areas of concern. .22. What problems did 9-11 Introduce for the Internet?The events of September 9, 2001, have since defined much of our daily lives and particularly our political concerns. The government, for its part, had to explain a massive intelligence failure. Foreign enemies had mounted horrifyingly successful attacks, producing more American casualties on American soil in a single day than any event since the Civil War. The Internet was quickly identified as a key element in the ability of this hidden enemy to plan, communicate, and to execute the attacks, soon defined almost universally not as a crime, but as an act of war. The War Against Terror soon followed, a war that continually expands to include other theaters, and to involve ever more actors. Even the seemingly endless and unchanging Israeli-Palestinian conflict is now dominated by the language of the War Against Terror. We have argued that the identification of the Internet as a key factor in understanding the events of 9-11 is absolutely correct. If anything, the changes in social, political, and economic structures resultant from the impact of the Internet relate even more directly to the events of 9-11 than is generally understood. [56] Given the manifold failure of the legal and intelligence structure before 9-11 to prevent its atrocities, Congress quickly began making sweeping changes, which may well directly affect the Internet. To date the most important of these was the "USA PATRIOT Act " [57] The Patriot Act, passed six weeks after the events, immediately superceded a legal structure that had been decades in the making. Few, if any of its elements have been utilized in a court of law, let alone tested against constitutional protections. In addition, a number of new bureaucracies were created, such as the Office of Homeland Security headed by former Governor Tom Ridge, and the White House Office of Cyberspace Security headed by Richard Clarke, "Special Advisor to the President for Cyberspace Security." .23. What problems face the Internet now?At this point, many issues are unknown and unknowable, because we cannot foretell how the new structure created by the Patriot Act and the proliferation of security-related agencies will affect the Internet. Nor, of course, are we ourselves sure as to how it should be affected. We do not want terrorists to be able to plan additional catastrophic attacks. Neither, however, do we want to surrender our ability to communicate electronically, nor do we want to see the emerging economic model created by the Internet stifled before it can mature in order to prevent such attacks. The question, of course, is what is an appropriate middle ground: How much are we willing to pay for security? It is clear that concerns for civil liberties and human rights, and for the freedom of the Internet community to communicate with a minimum of interference have been swept away in a tide of fear and concerns for the most basic of human rights, the right to life itself. An indication of the changes we have undergone might be this statement on the welcome or index page of "Echelonwatch" a group supported by the American Civil Liberties Union and several other watchdog groups particularly concerned about electronic freedoms: We at EchelonWatch are deeply saddened by the terrible events of September 11. We extend our deepest sympathies to the victims and their families. We support vigorous and appropriate actions by intelligence and law enforcement agencies to prevent more attacks from taking place. The goal of EchelonWatch is not to disband legitimate intelligence operations but to insist that they be subject to proper oversight. [58] The apologetic tone of this introduction (although it goes on in stronger language discussing the importance of adequate protection against abuses of ECHELON) accurately conveys the environment in which we now live. Any questioning of the costs of security potentially exposes the author to immediate criticism. Most Americans, conditioned by years of media-driven alarms about pornography on the Internet, child-abuse, cyber-stalking, electronic theft, and now, terrorists, would probably welcome just about any set of conditions intended to protect them against these threats. For example: A Harris poll conducted in October of 2001 found that: - 63% of Americans favored the monitoring of Internet discussions and chat rooms.

- 54% favored expanded monitoring of cell phones and e-mail. [59]

The provisions of the Patriot Act are far-reaching. [60] It is clear that whatever else the act may mean, Carnivore will be used much more often, and with far fewer safeguards than earlier. Recent informaiton suggests that hundreds of thousands of subpoenas have been issued since the passage of the Patriot Act, and the number may be doubling monthly. [61] . The Patriot Act also deliberately reduces the line between foreign and domestic intelligence gathering, making it probable that ECHELON will be used domestically if it has not been so used earlier. To say that such groups as the Electronic Frontier Foundation are very alarmed would be a considerable understatement. [62] In addition, a climate has been created which greatly facilitates decisions that would have been unlikely in the earlier climate in which privacy concerns took precedence over security. [63] A specific example of this factor is the recent enforcement of laws prohibiting the export of so-called "strong" encryption tools. Because of the outcry from industry and the fact that it was almost impossible to prevent such exports in any event, this law had not been enforced earlier. As a result, exporters had grown cavalier about the law. Recently the State Department announced a prosecution. [64] Although it is perhaps too early to point with alarm at the Patriot Act and accompanying changes, it is certainly appropriate to assume that the Internet and its usage will be greatly impacted. .24. What changes to the Internet are contemplated?While it is very difficult to foresee what the future might hold for the Internet, the creation of current security structures has been proceeding in an orderly and highly planned way and we are probably justified in speculating that the roots of the immediate future are at least dimly visible at present. [65] A major "National Announcement to Secure Cyberspace" reportedly is planned for the summer of 2002. The current stage of the process consists of a questionnaire "Questions to be Addressed" [66] divided into sections aimed at stakeholders such as: the home user and small business; major enterprises; the federal government; the private sector; state and local government; and higher education. Whether public opinion is in fact currently being consulted or the ground simply being laid politically for sweeping changes is impossible to know. EDUCAUSE, "a nonprofit association whose mission is to advance higher education by promoting the intelligent use of information technology" [67] is coordinating the response of the educational community to the questionnaire. Interestingly, the information technology industry was informed of these plans more than four months earlier, and began working up its responses immediately. Paul Kurtz, the Director of Critical Infrastructure Protection said in January "Much of the writing is under way now"230;We want a document that is largely authored by the private sector." [68] .25. What changes to the Internet are possible?The "Questions to be Addressed" hints at several possible outcomes. The present Internet, of course, has largely grown rather than being planned in any substantial fashion, and it sometimes seems that chaos and anarchy are necessarily characteristic of it. It seems to be secure from certain sorts of centralization simply because of its inchoate nature. But in "Questions to be Addressed" a number of methods are suggested whereby the government might create any sort of infrastructure it might wish with a minimum of expense: - Best practices: At several points it is asked whether or not national best practices should be adopted by particular industries. These would be defined, one assumes, by industry in consultation with national security agencies.

- Insurance best practices are referred to at several points. It would be relatively simple to encourage insurance companies to cover only customers that conform to "best practices for security."

- Government support for valuable subsidies for digital communication conditioned upon certain sorts of security arrangements: One question (Level 1-5) asks "If the federal government acts to facilitate more rapid deployment of broadband connectivity to the home user and small business, what cyberspace security requirements should be a condition of Federal support? This sort of federal carrot could be successful in inducing many possible changes, one assumes.

- Licensing and regulation: Above all the government has the vast power to regulate, to permit, and to make illegal certain sorts of practices. Question Level 4-11 simply asks: "Should software, hardware, and IT security consultants be certified, and if so, how and by whom?" Given the ability to certify and license every element of the Internet from computer software to routers and ISP personnel, any sort of security arrangement is possible.

- Another thread running through the questionnaire is the issue of a segmented Internet. Several of the questions imply that some believe that federal agencies might well withdraw to their own, more secure intranet, taking their content from the public internet. This idea has been supported in the past by Richard Clark, the new "Cyberspace Security Czar." It seems to be one highly probable outcome of the process of reconsidering the security of the Internet. There are also reasons to believe that an entire new Internet structure may well be constructed, with much more attention paid to security issues. [69]

- Above all it should be realized that the Internet is not, in fact, an infinite network, however much it may seem like one. All of the traffic in the United States passes through fewer than one hundred nodes or choke points. Traffic entering and leaving the United States must pass through far fewer points. An effort to monitor all traffic through such nodes is well within current technological capabilities, given adquate investment and a permissive legal framework.