- Cambridge Dictionary +Plus

Translation of empirical – English–Urdu dictionary

Your browser doesn't support HTML5 audio

(Translation of empirical from the Cambridge English–Urdu Dictionary © Cambridge University Press)

Examples of empirical

Translations of empirical.

Get a quick, free translation!

Word of the Day

scuba diving

the sport of swimming underwater with special breathing equipment

Never say die! (Idioms and phrases in newspapers)

Learn more with +Plus

- Recent and Recommended {{#preferredDictionaries}} {{name}} {{/preferredDictionaries}}

- Definitions Clear explanations of natural written and spoken English English Learner’s Dictionary Essential British English Essential American English

- Grammar and thesaurus Usage explanations of natural written and spoken English Grammar Thesaurus

- Pronunciation British and American pronunciations with audio English Pronunciation

- English–Chinese (Simplified) Chinese (Simplified)–English

- English–Chinese (Traditional) Chinese (Traditional)–English

- English–Dutch Dutch–English

- English–French French–English

- English–German German–English

- English–Indonesian Indonesian–English

- English–Italian Italian–English

- English–Japanese Japanese–English

- English–Norwegian Norwegian–English

- English–Polish Polish–English

- English–Portuguese Portuguese–English

- English–Spanish Spanish–English

- English–Swedish Swedish–English

- Dictionary +Plus Word Lists

- English–Urdu Adjective

- Translations

- All translations

To add empirical to a word list please sign up or log in.

Add empirical to one of your lists below, or create a new one.

{{message}}

Something went wrong.

There was a problem sending your report.

- Dictionaries

- English Urdu

- English Hindi

- Arabic Urdu

- English Phrases

- English Idioms

- Synonyms & Definitions

- English to Urdu

- empirical Meaning

Empirical Meaning in Urdu

Empirical meaning in Urdu is Ami (عملی) .Similar words of Empirical are also commonly used in daily talk like as Empirically, and Empirical Formula.Pronunciation of Empirical in roman Urdu is "Ami" and Translation of Empirical in Urdu writing script is عملی .

- Empirical forula, formula.

- (a.) Pertaining to, or founded upon, experiment or experience; depending upon the observation of phenomena; versed in experiments.

Empirical Urdu Meaning with Definition

Empirical is an English word that is used in many sentences in different contexts. Empirical meaning in Urdu is a عملی - Ami. Empirical word is driven by the English language. Empirical word meaning in English is well described here in English as well as in Urdu. You can use this amazing English to Urdu dictionary online to check the meaning of other words too as the word Empirical meaning.

Finding the exact meaning of any word online is a little tricky. There is more than 1 meaning of each word. However the meaning of Empirical stated above is reliable and authentic. It can be used in various sentences and Empirical word synonyms are also given on this page. Dictionary is a helpful tool for everyone who wants to learn a new word or wants to find the meaning. This English to Urdu dictionary online is easy to use and carry in your pocket. Similar to the meaning of Empirical, you can check other words' meanings as well by searching it online.

English Urdu Dictionary | انگریزی اردو ڈکشنری

The keyboard uses the ISCII layout developed by the Government of India. It is also used in Windows, Apple and other systems. There is a base layout, and an alternative layout when the Shift key is pressed. If you have any questions about it, please contact us.

empirical - Meaning in Urdu

Sorry, exact match is not available in the bilingual dictionary.

We are constantly improving our dictionaries. Still, it is possible that some words are not available. You can ask other members in forums, or send us email. We will try and help.

Definitions and Meaning of empirical in English

Empirical adjective.

تجربہ کیا ہوا , مجرب

- "an empirical basis for an ethical theory"

- "an empirical treatment of a disease about which little is known"

- "empirical data"

- "empirical laws"

- "empiric treatment"

What is another word for empirical ?

Sentences with the word empirical

Words that rhyme with empirical

English Urdu Translator

Words starting with

What is empirical meaning in urdu.

Other languages: empirical meaning in Hindi

Tags for the entry "empirical"

What is empirical meaning in Urdu, empirical translation in Urdu, empirical definition, pronunciations and examples of empirical in Urdu.

SHABDKOSH Apps

Ad-free experience & much more

Tips of essay writing for children

Using simple present tense

Direct and Indirect speech

Our Apps are nice too!

Dictionary. Translation. Vocabulary. Games. Quotes. Forums. Lists. And more...

Vocabulary & Quizzes

Try our vocabulary lists and quizzes.

Vocabulary Lists

We provide a facility to save words in lists.

Basic Word Lists

Custom word lists.

You can create your own lists to words based on topics.

Login/Register

To manage lists, a member account is necessary.

Share with friends

Social sign-in.

Translation

If you want to access full services of shabdkosh.com

Please help Us by disabling your ad blockers.

or try our SHABDKOSH Premium for ads free experience.

Steps to disable Ads Blockers.

- Click on ad blocker extension icon from browser's toolbar.

- Choose the option that disables or pauses Ad blocker on this page.

- Refresh the page.

Spelling Bee

Hear the words in multiple accents and then enter the spelling. The games gets challenging as you succeed and gets easier if you find the words not so easy.

The game will show the clue or a hint to describe the word which you have to guess. It’s our way of making the classic hangman game!

Antonym Match

Choose the right opposite word from a choice of four possible words. We have thousand of antonym words to play!

Language Resources

Get our apps, keep in touch.

- © 2024 SHABDKOSH.COM, All Rights Reserved.

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

Liked Words

Shabdkosh Premium

Try SHABDKOSH Premium and get

- Ad free experience.

- No limit on translation.

- Bilingual synonyms translations.

- Access to all Vocabulary Lists and Quizzes.

- Copy meanings.

Already a Premium user?

Translation of "empirical" into Urdu

تجربی is the translation of "empirical" into Urdu. Sample translated sentence: Roman citizens in Philippi and throughout the Roman Empire were proud of their status and enjoyed special protection under Roman law. ↔ رومی شہری ہونے کی وجہ سے اُنہیں وہ حقوق حاصل تھے جو اُس وقت بہت ہی کم لوگوں کے پاس تھے۔

Pertaining to or based on experience. [..]

English-Urdu dictionary

pertaining to or based on experience

Show algorithmically generated translations

Automatic translations of " empirical " into Urdu

Phrases similar to "empirical" with translations into urdu.

- Ghaznavid Empire سلطنت غزنویہ

- Ottoman Empire سلطنت عثمانیہ

- Holy Roman Empire Baadshah-e-Rum-e-Muqaddas · مقدس رومی سلطنت

- Gupta Empire گپتا

- British Empire سلطنت برطانیہ

- Inca Empire انکا

- Mughal Empire مغلیہ سلطنت

- british empire سلطنت برطانیہ

Translations of "empirical" into Urdu in sentences, translation memory

Empiric meaning in Urdu

Empiric sentence, empiric synonym, empiric definitions.

1) Empiric , Empirical : تجرباتی , مشاہداتی : (adjective) derived from experiment and observation rather than theory.

Empirical laws. Empirical data. + More An empirical treatment of a disease about which little is known.

Useful Words

Data-Based : مشاہداتی , Confirmable : تصدیق کے قابل , A Priori : قیاس پر مبنی , Scientific Method : سائنسی طریقہ , Transcendental Philosophy : علویت , Demonstrate : ظاہر کرنا , Ascertain : تعین کرنا , Stargazing : ستارہ بینی نجوم , Unobservable : ناقابل مشاہدہ , Shadow : پناہ , Commemorate : منانا , Contemplation : غور و فکر , Alert : چوکس , Ascertained : دریافت شدہ , Intuitive : الہامی , Sampler : پرکھنے کی جگہ , Surveillance : کڑی نگرانی , Experienced : تجربہ رکھنے والا , Experience : مشاہدہ , Air Reconnaissance : ہوائی نگرانی , Art : فن , Cardiac Monitor : دل کی نگرانی کا آلہ , Clutter : شور , Fluoroscope : لا شعاع نما , A. A. Michelson : امریکی ماہر طبعیات , Clinical : طبی , Watchtower : پہرے داروں کا مینار , Paracelsus : سوئٹزرلینڈ کا معالج , Theorize : نظریہ سازی کرنا , Educationalist : ماہر تعلیم , Atomic Theory : جوہری نظریہ

Useful Words Definitions

Data-Based: relying on observation or experiment.

Confirmable: capable of being tested (verified or falsified) by experiment or observation.

A Priori: based on hypothesis or theory rather than experiment.

Scientific Method: a method of investigation involving observation and theory to test scientific hypotheses.

Transcendental Philosophy: any system of philosophy emphasizing the intuitive and spiritual above the empirical and material.

Demonstrate: establish the validity of something, as by an example, explanation or experiment.

Ascertain: establish after a calculation, investigation, experiment, survey, or study.

Stargazing: observation of the stars.

Unobservable: not accessible to direct observation.

Shadow: refuge from danger or observation.

Commemorate: mark by some ceremony or observation.

Contemplation: a long and thoughtful observation.

Alert: engaged in or accustomed to close observation.

Ascertained: discovered or determined by scientific observation.

Intuitive: obtained through intuition rather than from reasoning or observation.

Sampler: an observation station that is set up to make sample observations of something.

Surveillance: close observation of a person or group (usually by the police).

Experienced: having experience; having knowledge or skill from observation or participation.

Experience: the content of direct observation or participation in an event.

Air Reconnaissance: reconnaissance either by visual observation from the air or through the use of airborne sensors.

Art: a superior skill that you can learn by study and practice and observation.

Cardiac Monitor: a piece of electronic equipment for continual observation of the function of the heart.

Clutter: unwanted echoes that interfere with the observation of signals on a radar screen.

Fluoroscope: an X-ray machine that combines an X-ray source and a fluorescent screen to enable direct observation.

A. A. Michelson: United States physicist (born in Germany) who collaborated with Morley in the Michelson-Morley experiment (1852-1931).

Clinical: relating to a clinic or conducted in or as if in a clinic and depending on direct observation of patients.

Watchtower: an observation tower for a lookout to watch over prisoners or watch for fires or enemies.

Paracelsus: Swiss physician who introduced treatments of particular illnesses based on his observation and experience; he saw illness as having an external cause (rather than an imbalance of humors) and replaced traditional remedies with chemical remedies (1493-1541).

Theorize: construct a theory about.

Educationalist: a specialist in the theory of education.

Atomic Theory: a theory of the structure of the atom.

Related Words

A Posteriori : ثبوت طلب , Existential : تجرباتی

Empiric in Book Titles

Directions in Empirical Literary Studies: In Honor of Willie Van Peer. Contemporary Issues in the Empirical Study of Crime. A Guide to Empirical Research in Communication: Rules for Looking. Empirical Studies of Programmers: Second Workshop. Dynamic Stochastic Models from Empirical Data.

Next of Empiric

Empirical : derived from experiment and observation rather than theory.

Previous of Empiric

Emphasised : spoken with emphasis.

Download Now

Download Wordinn Dictionary for PC

- Common Words

- English to Urdu

Empirical meanings in Urdu

Empirical meanings in Urdu are تَجَربہ پر بُنیاد ہونا, عملی, تَجَرباتی Empirical in Urdu. More meanings of empirical, it's definitions, example sentences, related words, idioms and quotations.

Empirical Definitions

Please find 2 English and 1 Urdu definitions related to the word Empirical.

- (adjective) : derived from experiment and observation rather than theory

- (adjective) : relying on medical quackery

- صِرَف مُشاہدات پَر مَبنی ہونا اور اِس کا سائنسی تحقیقات سے کوئی تَعلُّق نَہ ہونا

As many political writers have pointed out, commitment to political equality is not an empirical claim that people are clones.

- Steven Pinker

The best thing about science is that hard, empirical answers are always there if you look hard enough. The best thing about religion is that the very absence of that certainty is what requires - and gives rise to - deep feelings of faith.

- Jeffrey Kluger

I had some of the students in my finance class actually do some empirical work on capital structures, to see if we could find any obvious patterns in the data, but we couldn't see any.

- Merton Miller

It is that of increasing knowledge of empirical fact, intimately combined with changing interpretations of this body of fact - hence changing general statements about it - and, not least, a changing a structure of the theoretical system.

- Talcott Parsons

More words related to the meanings of Empirical

Next to Empirical “ !--> Embolism ”

Previous to Empirical “ !--> Ember ”

More words from Urdu related to Empirical

View an extensive list of words below that are related to the meanings of the word Empirical meanings in Urdu in Urdu.

انتظامی عملی اطلاقی

Idioms related to the meaning of Empirical

| English | اردو |

|---|---|

What are the meanings of Empirical in Urdu?

Meanings of the word Empirical in Urdu is عملی - amli. To understand how would you translate the word Empirical in Urdu, you can take help from words closely related to Empirical or it’s Urdu translations. Some of these words can also be considered Empirical synonyms. In case you want even more details, you can also consider checking out all of the definitions of the word Empirical. If there is a match we also include idioms & quotations that either use this word or its translations in them or use any of the related words in English or Urdu translations. These idioms or quotations can also be taken as a literary example of how to use Empirical in a sentence. If you have trouble reading in Urdu we have also provided these meanings in Roman Urdu.

We have tried our level best to provide you as much detail on how to say Empirical in Urdu as possible so you could understand its correct English to Urdu translation. We encourage everyone to contribute in adding more meanings to MeaningIn Dictionary by adding English to Urdu translations, Urdu to Roman Urdu transliterations and Urdu to English Translations. This will improve our English to Urdu Dictionary, Urdu to English dictionary, English to Urdu Idioms translation and Urdu to English Idioms translations. Although we have added all of the meanings of Empirical with utmost care but there could be human errors in the translation. So if you encounter any problem in our translation service please feel free to correct it at the spot. All you have to do is to click here and submit your correction.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

What do you mean by empirical.

Meaning of empirical is عملی - amli

Whats the definition of empirical?

- derived from experiment and observation rather than theory

- relying on medical quackery

What is the synonym of empirical?

Synonym of word empirical are practicum, practicals, practic, faunistic, pragmatical, practical, practicableness, practicable, actuating, applied

What are the idioms related to empirical?

- Honesty is the best policy

- Practical joke

- Pragmatic sanction

- Pure science

What are the quotes with word empirical?

- As many political writers have pointed out, commitment to political equality is not an empirical claim that people are clones. — Steven Pinker

- The best thing about science is that hard, empirical answers are always there if you look hard enough. The best thing about religion is that the very absence of that certainty is what requires - and gives rise to - deep feelings of faith. — Jeffrey Kluger

- I had some of the students in my finance class actually do some empirical work on capital structures, to see if we could find any obvious patterns in the data, but we couldn't see any. — Merton Miller

- It is that of increasing knowledge of empirical fact, intimately combined with changing interpretations of this body of fact - hence changing general statements about it - and, not least, a changing a structure of the theoretical system. — Talcott Parsons

Top Trending Words

Dictionaries

- Urdu Dictionary

- Punjabi Dictionary

- Pashto Dictionary

- Balochi Dictionary

- Sindhi Dictionary

- Saraiki Dictionary

- Brahui Dictionary

- Names Dictionary

- More Dictionaries

Language Tools

- Transliteration

- Inpage Converter

- Web Directory

- Telephone Directory

- Interesting

- Funny Photos

- Photo Comments

Facebook Covers

- Congratulations

- Independence Day

- Love/Romantic

- Miscellaneous

SMS Messages

- Good Morning

- Baap or Beta

- Miya or Biwi

- Ustaad or Shagird

- Doctor or Mareez

- Larka or Larki

- Mehndi Designs

- #latestnews

- #thisdayinhistory

- #ReleaseDate

- Food Recipes

- Pakistan Flag Display Photo

- Farsi Dictionary

- Name Dictionary

empirical Urdu Meaning

Urdu Meanings

iJunoon official Urdu Dictionary

International Languages

Meaning for empirical found in 10 Languages.

Near By Words

- empirically

Sponored Video

- ABBREVIATIONS

- BIOGRAPHIES

- CALCULATORS

- CONVERSIONS

- DEFINITIONS

Vocabulary

Translations

How to say empirical in urdu ɛmˈpɪr ɪ kəl em·pir·i·cal, would you like to know how to translate empirical to urdu this page provides all possible translations of the word empirical in the urdu language..

- تجرباتی Urdu

Discuss this empirical English translation with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe. If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

You need to be logged in to favorite .

Create a new account.

Your name: * Required

Your email address: * Required

Pick a user name: * Required

Username: * Required

Password: * Required

Forgot your password? Retrieve it

Citation

Use the citation below to add this definition to your bibliography:.

Style: MLA Chicago APA

"empirical." Definitions.net. STANDS4 LLC, 2024. Web. 6 Aug. 2024. < https://www.definitions.net/translate/empirical/EN >.

The Web's Largest Resource for

Definitions & translations, a member of the stands4 network, free, no signup required :, add to chrome, add to firefox, browse definitions.net, are you a words master, pose a threat to; present a danger to, Nearby & related entries:.

- empire test pilots' school

- empire today

- empire-building

- empiric adj

- empirical adj

- empirical data

- empirical distribution function

- empirical ego

- empirical evidence

- empirical formula noun

Alternative searches for empirical :

- Search for empirical on Amazon

Search results

Saved words

Showing results for "research"

Research and development.

(صنعت وغیرہ میں ) جدّت طرازی، ایجاد و اختراع اور مصنوعات کی بہتری کے لیے کوشش ۔.

research-scholar

Operational research.

سائنسی اصولوں کا کاروباری انتظامیہ پر اطلاق تاکہ پیچیدہ فیصلوں کے لیے ٹھوس بنیاد مہیا ہوسکے۔.

duusraa-cha.Daav

Duusrii-chot, urdu words for research, research के उर्दू अर्थ, research کے اردو معانی, tags for research.

English meaning of research , research meaning in english, research translation and definition in English. research का मतलब (मीनिंग) अंग्रेजी (इंग्लिश) में जाने | Khair meaning in hindi

Top Searched Words

today, present moment

Citation Index : See the sources referred to in building Rekhta Dictionary

Critique us ( research )

Upload image let’s build the first online dictionary of urdu words where readers literally ‘see’ meanings along with reading them. if you have pictures that make meanings crystal clear, feel free to upload them here. our team will assess and assign due credit for your caring contributions.">learn more.

Display Name

Attach Image

Delete 44 saved words?

Do you really want to delete these records? This process cannot be undone

Want to show word meaning

Do you really want to Show these meaning? This process cannot be undone

Download Mobile app

Urdu poetry, urdu shayari, shayari in urdu, poetry in urdu

The best way to learn Urdu online

World of Hindi language and literature

Online Treasure of Sufi and Sant Poetry

Saved Words No saved words yet

Support rekhta dictionary. donate to promote urdu.

The Rekhta Dictionary is a significant initiative of Rekhta Foundation towards preservation and promotion of Urdu language. A dedicated team is continuously working to make you get authentic meanings of Urdu words with ease and speed. Kindly donate to help us sustain our efforts towards building the best trilingual Urdu dictionary for all. Your contributions are eligible for Tax benefit under section 80G.

Meaning of Empirical in Urdu

Meaning and Translation of Empirical in Urdu Script and Roman Urdu with Wikipedia Reference,

Urdu Meaning or Translation

| empirical | tajribati | تجرباتي | |

| empirical | amli | عملي |

Not been touched for over 3 years. |

Previous Word

| Next Word

|

Jump to navigation

|

| |

Tawaifbaazi: Courtesans and Prostitutes in Urdu Hindi Literature

Call for Chapters

Tawaifbaazi : Courtesans and Prostitutes in Urdu Hindi Literature

Editor: Farkhanda Shahid Khan

Important Dates

September 05, 2024: Abstract Submission Deadline

September 19, 2024: Notification of Abstract Decision

November 25, 2024: Full Chapter Due

The intersection of literature and societal issues has long served as a platform for introspection, critique, and exploration. In Urdu Hindi literature, the portrayal of courtesans and prostitutes has been a source of both fascination and controversy, reflecting the intricate interplay of culture, ethics, and human existence. Ismat Chughtai, Sa‘adat Hasan Manto, Krishan Chander, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Agha Shorish Kashmiri, Munshi Premchand, and many other writers of Urdu and Hindi literature have intricately depicted the human experiences, societal norms, and individual choices through their literary works. This call invites scholars, researchers, and practitioners to contribute chapters to an edited collection that scrutinizes the depiction of courtesans and prostitutes in Urdu Hindi literature, exploring contemporary themes and critical perspectives.

This volume intends to make a substantial contribution to the academic field of gender studies, social discourse and South Asian literature.

Chapters are invited that explore, but are not limited to, the following themes:

- Historical Context and Evolution of Prostitution in Urdu Hindi Literature

- Courtesans as Patrons and Practitioners of Art Forms

- Transgressive Narratives in Urdu Hindi Literature

- Eroticism, Desire and Sensuality in representation of Prostitution

- Intersectionality, identity and Marginalization of Courtesans and Prostitutes

- Forbidden Love and Tragic Romance between Courtesans/Prostitutes and their Clients

- Global Perspectives on Courtesans and Prostitutes in Urdu Hindi Literature

- Agency and Voice of Courtesans and Prostitutes

- Feminist and Postcolonial Perspectives on Courtesans and Prostitutes in Urdu Hindi Literature

- Transnational prostitution as a form of Female Migration

- Feminist debates on Prostitution, Pornography and Women

- Health Humanities: Reproductive Health and Prostitution in Urdu Hindi Literature

- Social Commentary on Prostitution and Reforms

- Courtesans, Prostitutes and International Human Rights

- Urban Spaces and Modernity Shaping Narratives on Courtesans and Prostitutes in Urdu Hindi Literature

Kindly submit an abstract of 200-250 words accompanied by a brief author biography to [email protected] by September 05, 2024.

Submission guidelines will be provided upon acceptance of the abstract. Each submission will undergo a double blind peer-review process and the book will be published by a prestigious academic publisher in June 2025. For inquiries and further information, please contact us at [email protected]

We look forward to engaging in a rich and thought-provoking dialogue on this significant yet understudied aspect of Urdu Hindi literature.

About the Editor

Farkhanda Shahid Khan is a feminist researcher, activist, and academic. She teaches contemporary English literature at Government College University Faisalabad. Khan works on Feminism, Marxism, Culture, and Gender & Sexuality with a focus on the Global South. Currently, she is a doctoral fellow in the School of Literatures, Languages & Cultures at the University of Edinburgh and her research delves into the red light districts and brothel quarters in India and Pakistan.

- English To Urdu

- Urdu To English

- Roman Urdu To English

- English To Hindi

- Hindi To English

- Roman Hindi To English

- Translate English To Urdu

- Translate Urdu To English

- Translate English To Hindi

- Translate Hindi To English

- English Meaning In Urdu

- Urdu Meaning In English

- Urdu Lughat

- English Meaning In Hindi

- Hindi Meaning In English

- Hindi Shabdkosh

- English To Urdu Dictionary

- Research Meaning In Urdu Dictionary

Research Meaning In Urdu

Research Meaning in English to Urdu is تحقیق, as written in Urdu and Tehqeeq, as written in Roman Urdu. There are many synonyms of Research which include Analysis, Delving, Experimentation, Exploration, Groundwork, Inquest, Inquiry, Inquisition, Investigation, Legwork, Quest, Scrutiny, Probe, Probing, Fishing Expedition, etc.

[ri-surch, ree-surch]

Definitions of Research

n . Diligent inquiry or examination in seeking facts or principles; laborious or continued search after truth.

n . Systematic observation of phenomena for the purpose of learning new facts or testing the application of theories to known facts; -- also called scientific research. This is the research part of the phrase u201cresearch and developmentu201d (R&D).

transitive v . To search or examine with continued care; to seek diligently.

How To Spell Research [ri-surch, ree-surch]

Origin of Research Late 16th century: from obsolete French recerche (noun), recercher (verb), from Old French re- (expressing intensive force) + cerchier ‘to search’.

Synonyms For Research , Similar to Research

Antonyms for research , opposite to research, more word meaning in urdu, free online dictionary, word of the day.

[verb In-krees; Noun In-krees]

Izafah Karna

Top Trending Words

| طاغوت : سر کش | |

| یونانی دیو مالا میں ایک چھوٹا سمندری دیوتا | |

| پشتو زبان | |

| اسم | |

| اسٹابری پھل | |

| گرم کہانی | |

| بِسمِ اللہِ الرَّحم?نِ الرَّحِیم | |

| حب | |

| بیوی | |

| عورتوں میں ہم جنس پرست | |

| مافیا | |

| عضو تناسل | |

| فوطیرون | |

| جنسی | |

| افراہیم | |

| جزو ترکیبی بمعنی حیاتی | |

| اسلام | |

| جلق | |

| شعیہ | |

| اللہ |

- Open access

- Published: 01 August 2024

The place of health in the EU-CELAC interregional cooperation from 2005 to 2023: a historical, empirical and prospective analysis

- Carolina Salgado ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6808-2116 1

Globalization and Health volume 20 , Article number: 60 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

46 Accesses

Metrics details

Much has been said by actors from different fields and perspectives about the manifold changes in world affairs triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. In this context, it is to be expected that there will be impacts on long-standing partnerships such as the one between the European Union and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean Countries. However, few studies have demonstrated these impacts, either empirically, by uncovering their specificities or from a historical perspective, to allow for a reasonable methodological comparison of the patterns used to define the partnership and that have changed or have been affected in some way by the pandemic.

Through an in-depth qualitative assessment of primary and secondary sources, this article contributes to this research gap. It analyzes the patterns and changes or impacts in light of two strands of behavior that can make sense of EU-CELAC health cooperation—revisionist or reformist. The findings show an economy-driven health agenda as a new pattern of cooperation, which derives from EU reformist behavior after the pandemic.

Conclusions

The EU power to enforce its priorities in the context of health cooperation with CELAC is the main factor that will define how (and not just which) competing interests and capacities will be accommodated. The relevance of the study to the fields of global governance for health, interregional health cooperation and EU foreign policy is threefold. It shows us i.how two more international regimes are easily intertwined with health—trade and intellectual property—with the potential to deepen asymmetries and divergences even between long-standing strategic partners; ii.contrary to the idea that reformist behaviors are only adopted by actors who are dissatisfied with the status quo, the study shows us that the reformist actor can also be the one who has more material power and influence and who nevertheless challenges the success of cooperation in the name of new priorities and the means to achieve them; and iii.how the EU will find it difficult to operationalize its new priorities internally, among states and private actors, and with those of CELAC, given the history of intense disputes over health-related economic aspects.

Introduction

Much has been said by actors from different fields and perspectives about the manifold changes in world affairs triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. Although it was not the first nor the deadliest pandemic in contemporary epidemiological history, it has reinforced, during and after its eclosion (January-March 2020 to May 2023), some disturbing truths underpinning those claims about changes, such as capitalism having no resilience, nationalism comes before cooperation, crises happen simultaneously in cascade effect and, unfortunately, in a number of cases, money matters more than lives.

In this context, it is to be expected that there will be impacts on long-standing partnerships such as the one between the European Union (EU) and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean Countries (CELAC), which was initiated even before the formalization of CELAC occurred at the Summit of the Unity of Latin America and the Caribbean, in the Riviera Maya (Mexico), in 2010. In fact, experts agree that 1999 was a landmark, with the institutionalization of EU-LAC Strategic Partnership, and that “the creation of CELAC in 2010 brought an opportunity for a more structured EU-LAC dialogue, which became organized into EU-CELAC Summits and Action Plans” [ 39 ]:IX).

As the examples provided in this research demonstrate with respect to the health area, it is important to note that the EU-CELAC partnership builds on normative and ideational sharing of values and principles historically consolidated, which drives their respective interests and means regarding policies´ implementation. This is why the partnership has been considered here since before CELAC was formalized, and this understanding is supported by publications released by the European Commission and other studies on different areas [ 5 , 51 ]. It is considered that we cannot grasp recent developments of specific cooperative engagements without knowing how they came into being, especially when the bi-regional relations have a long road.

Zooming a bit in this road, although the EU-CELAC partnership is multifaceted – involving areas such as the strengthening of human rights and democracy; cooperative ties in health, science and technology; support of regionalism and regional spaces for debate and joint actions – it is clear that trade links remain at the center. EU-CELAC experts explain that “various interregional association agreements, economic partnership agreements, multiparty trade agreements and bilateral framework agreements are components of this relationship” [ 39 ]:VII), reinforcing each other as trade priorities despite recent changes in the global trade landscape, especially with regard to China's role in CELAC. As for researches, it is common to find compilations [ 57 ] and comparative studies [ 56 , 61 ] involving EU-CELAC manifold agendas, mainly due to the creation of the EU-LAC Foundation in 2010 as a tool of the partnership that feeds into the intergovernmental dialogue.

In contrast, few studies have demonstrated impacts of systemic changes (such as the latest pandemic) on EU-CELAC partnership, either empirically, by uncovering their specificities, or from a historical perspective, to allow for a reasonable methodological comparison of the patterns used to define the partnership and that have changed or have been affected in some way by these changes. This article contributes to this research gap through a thorough analysis of empirical documents produced within the EU-CELAC health cooperation over time. In doing so, it also contributes to the literature on EU regional health cooperation, emphasizing the specificities of this case that can be mobilized, in further research, in relation to some of the EU’s other regional health partnerships. Footnote 1 I give a brief overview of this literature and then present the methods of analyzes, explaining why and how they were employed through the study.

The literature on EU regional health cooperation [ 35 , 52 , 55 , 62 ], like other regional organizations, draws on the concept of ‘global health governance’ which, for systemic reasons that have to do with globalization [ 54 ], emerged simultaneously with the social determinants of health, an approach systematized by the WHO´s Commission on Social Determinants of Health in 2008 [ 3 ]. The approach and the related concept indicate that, since health issues are inevitably transnational, cooperation must incorporate a whole array of stakeholders. In this sense, regional organizations act as a bridge between global initiatives and national policy implementation. In the case of the EU, although it has a specific body for health policy within the Commission, which is the DG for Health and Consumers (DG SANCO), according to the Lisbon Treaty its mandate is to act as a complement to national policy-making. In order to do this, the EU establishes strategies Footnote 2 aiming at improving coherence of policy recommendations, “aligning member states on a similar value system for health improvement (…) and reinforce the regional institution´s role as a global actor in health governance” [ 55 ]:2–3). Such a role is based on a horizontal integration of public health, considered as a prime objective in all sectors of policy-making [ 53 ]. Together with DG SANCO, other EU agencies Footnote 3 are important partners within a wider network that includes a WHO EURO, a regional office of the WHO based in Copenhagen and, very important, the European Public Health Alliance (EPHA), a civil society organization for health cooperation.

The article offers a systematization of the patterns of EU-CELAC cooperation in health and their multilateral engagement from a historical perspective, from 2005 until the present, to empirically understand how and what has changed in such patterns since the COVID-19 pandemic. The systematization aims to analyze these changes in light of two strands of behavior that can make sense of EU-CELAC health cooperation – revisionist, meaning "reviewing previous disagreements", or reformist, meaning "setting new priorities". I employ the inductive method of testing the hypothesis stated below through the qualitative content analysis of thirty primary sources available online and listed in the linked references, in addition to secondary literature that dialog directly with these sources. The inductive analysis has the main purpose of uncovering causal mechanisms and interactions effects underlying EU-CELAC health cooperation over time. I aim to understand precisely the logic behind the widespread assumption that the COVID-19 pandemic has triggered manifold changes in world affairs by taking the idea of change seriously. For doing that, the EU-CELAC health cooperation is a paradigmatic case-study because it allows us for a reasonable methodological comparison of the patterns used to define the partnership and that have changed or have been affected in some way by the pandemic.

The subsidiary hypothesis is the following: revisionist behavior is a common pattern among actors who are constantly engaged in interregional relations marked by great asymmetry of power, as is the case with CELAC and the EU in their history of cooperation. This behavior reflects the fact that diffusing the ideas and interests that make up common projects is far from simple [ 48 , 49 ]. Political coordination around the elements that define the object, instruments and mechanisms of cooperation is permeated by disputes informed by the different identities and worldviews of decision-makers and stakeholders [ 31 , 64 ]. As a result, we can expect a variety of mechanisms and outcomes for each project that, if qualitatively assessed, reveal relevant aspects about the disputes themselves and, therefore, about the politics of cooperation [ 36 , 37 ]. In contrast, reformist behavior denotes a significant change in the pattern of cooperation because it raises new priorities that reflect an internal review of foreign policy direction and that may not have been properly negotiated beforehand with counterparties. To the extent that this behavior reforms the cooperation space itself, impacting values and approaches that often happen to facilitate dialog, the reformist actor also challenges the success of the partnership in the name of his priorities and means to achieve them on a given international agenda.

By means of in-depth qualitative assessment of primary sources available online about the projects that paved the EU-CELAC interregional cooperation in health, with further mobilization of secondary literature directly related to these sources, I could identify patterns related to issue areas, outputs, practices and values that are found in all of them until the COVID-19 pandemic and that characterize a rationale of development through health, with a focus on social dimensions. Then, I put these sources in perspective of the EU-CELAC multilateral engagement by mapping the behavior of both partners within the Oslo Group Footnote 4 through their support of the resolutions approved in the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) over the period of the research, 2008–2020. Such endeavors are in section one, the findings of which indicate that biregional projects did reflect their foreign policy goals within the global governance for health, despite possible disagreements on specific targets, perceptions and methods of interaction. In the second section, I turn to the period after the pandemic to assess what and how changes may have taken place. In sections one and two, I present the respective results in order to give a clearer understanding of which and how the referred primary sources were analyzed.

Preliminary discussion and research goal

By the end of 2021, in a political response to the pandemic, the European Commission set out the Global Gateway strategy, which was followed by the EU Global Health Strategy, launched in November 2022. My claim is that when one looks superficially at health strategy´s three policy priorities, there is not much difference regarding their previous health projects and the resolutions mostly supported by the EU and CELAC countries at UNGA in terms of language, of the way ideas are presented and discourses are written. However, going deeper in the primary sources and carefully analyzing priorities, guiding principles and lines of action of the EU Global Health Strategy, in addition to following news, press releases and communications available mainly in the website of DG International Partnerships, the research indicates that the kind of changes in EU-CELAC interregional cooperation in health, this time, reflects the dominance of EU interests. We can see that the main pattern of interregional cooperation moved from development through health , as it was in the previous projects embracing social cohesion, drug policies and policy-oriented health research, to the current economy-driven health development —a movement clearly propelled by an EU reformist behavior by means of elevating health technologies and manufacturing as priorities for cooperation with CELAC after the pandemic.

Notwithstanding the fact that such a move was propelled by the EU as observed from its sources that directly address health cooperation with CELAC after the pandemic, one must recognize that, by looking from CELAC, several actions and choices made throughout the pandemic might have influenced the adoption of EU´s changing behavior as displayed in its cooperation strategy with CELAC. It is worth highlighting some examples of CELAC´s initiatives in this regard, of which the CELAC Plan on Health Self-Sufficiency [ 12 ] discussed within the following sections is the main one. Approved by the XXI Summit of Foreign Ministers of CELAC, held on July 24, 2021 in Mexico, this Plan arises with the idea that Latin America and the Caribbean becomes an actor in the development and production of new vaccines, within the framework of a concerted regional health strategy. There are evidences to support this idea in the large number of technical meetings CELAC has promoted Footnote 5 in order to strength its institutional capacity facing the pandemic – linked to emergencies, preparedness and monitoring, in addition to access and production of medicines, vaccines and strategic supplies.

Moreover, another example seems critical in terms of potentially influence upon the EU: the distribution of respirators, syringes and needles, masks and diagnostic kits donated by China through CELAC. China's cooperation with the region has had to do with the production of vaccines and medicines and the transfer of technologies and sale of pharmaceutical supplies in the region. Therefore, this background allows us to say that: (i) the EU's cooperation with CELAC after the pandemic occurs in a geopolitical context where, on the one hand, China has made significant progress in cooperation with most Latin American countries and, on the other hand, the United States and Europe have lost hegemonic power in the CELAC countries; (ii) the EU´s interests reflected in its renewed strategy are embedded in such geopolitical context, therefore, in some sense reacting to CELAC´s initiatives that have emerged during the pandemic. In this way, the research goal falls upon the EU because changes in patterns used to define the partnership were openly triggered by the EU´s renewed cooperation strategy with CELAC. This fact reinforces the second point made in the abstract, regards the relevance of this study, which I retake here: contrary to the idea that reformist behaviors are only adopted by actors who are dissatisfied with the status quo, the study shows us that the reformist actor – in this case, the EU – can also be the one who has more material power and historical influence, and who nevertheless challenges the success of cooperation in the name of new priorities and the means to achieve them.

To advance the goal of the research—which is to understand how and what has changed in patterns used to define the partnership and which have changed or have been affected in some way by the COVID-19 pandemic—I systematize the analysis in terms of revisionist or reformist behavior. Although the initiatives are yet to be implemented and, therefore, we cannot empirically evaluate their outcomes and reactions, the in-depth qualitative research of several primary sources in addition to the historical path of the politics of cooperation in health between the EU and CELAC within a period of eighteen years in different settings allows me to say that we are witnessing a reformist behavior on the EU side. The EU has redirected its foreign policy with the Global Gateway and a number of instruments, such as Team Europe, and a significant amount of funding for different issue areas and regions. Economy-driven health development means that the EU has mobilized its economic power to promote health priorities whose means of implementation are constitutive parts of the main divergences in biregional relations with Latin America and the Caribbean, as will be seen below.

In the third section, therefore, I discuss the results. I take as a point of reference how historical differences in approaches to health between the two regions have been negotiated, with a focus on the issue of pharmaceutical manufacturing and health technologies. Its aim is to support a plausible interpretation of the impact that changing EU behavior and priorities may have on the EU-CELAC partnership in the field of health within the framework of the EU Global Gateway (2021–2027), in prospective terms. In the concluding section, I summarize the content and introduce avenues for further research.

The patterns of EU-CELAC cooperation in health and their multilateral engagement: a qualitative assessment of main initiatives between 2005 and 2019

The first interregional cooperation project with specific health concerns was “Strengthening the health sector in Latin America as a vector of social cohesion”, referred to as EUROsociAL/Salud, which was implemented between 2005 and 2009. In its website [ 22 ], we read that the contribution of health systems to social cohesion depends in large part on the equity of these systems in a broad sense. In this sense, health equity contemplates three dimensions: equity in the health status of individuals, access to services and treatments, and financing. The EUROsociAL programme assists with policies that address the first two.

EUROsociAL is multisector, being divided into five priorities that are part of the EU Cohesion Policy: administration of justice, education, taxation system, employment and health. The health sector, in turn, is divided into five areas: (i) development of social protection in health, (ii) good governance in health services, systems and hospitals, (iii) health services based on quality primary care and efficient and equal access to medication, (iv) public health policies and risk control, and (v) promotion of health policies in the community for the benefit of the most vulnerable and excluded sector [ 45 ]. The project is financed by the European Commission under the coordination of Spain (Fundación Internacional y para Iberoamérica de Administración y Políticas Públicas—FIIAPP), encompassing other European countries such as Italy, Germany and France. It also has two Latin American countries within the coordinating partners, which are Brazil (Escola Nacional de Saúde Pública Sergio Arouca—ENSP/Fiocruz) and Colombia (Agencia Presidencial de Cooperación Internacional de Colombia—APC), in addition to SICA (Sistema de la Integración Centroamericana).

As with other EU projects, EUROsociAL/Salud comes from the EU view that Latin America needs knowledge transfer to improve social cohesion and public policies. Therefore, these countries participate as receivers through a template of practices (inspections, workshops, internships, training activities, technical assistance), a timeline of exchanges, a set of goals to be achieved, and EU values that must be incorporated into mechanisms of social inclusion such as universal social protection, democratic participation, equality in the enjoyment of rights and access to opportunities. Although social cohesion was a main element of the EU-LAC Strategic Partnership initiated in 1999, we would need a better assessment of how such practices and exchanges took place in Peru, Panama and Uruguay, for instance.

The second project that can be considered part of the interregional cooperation in health is COPOLAD, the EU-CELAC Cooperation Programme on Drugs Policies, initiated in 2011 with EU funding [ 13 ]. Each phase has four years, and it is currently in its third phase, with a budget of €15 million from February 2021. It has nearly the same EU and LAC partners of EUROsociAL/Salud in addition to the EMCDDA (European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction), with a focus on promoting technical cooperation based on scientific evidence as well as political dialog on drug policies between Latin America, the Caribbean and the EU. As regards to objectives, we read that they “will be fully respectful of the national sovereignty of each country and will be based on the demand raised by the participating countries themselves” (COPOLAD website).

I have already made a qualitative assessment of COPOLAD elsewhere [ 60 ] and will not discuss here the criticisms we could raise about how the EU communicates the programme, in light of how practices take place and how LAC countries understand the cooperation. After more than ten years since task forces were designated for implementation, expressions such as triangular cooperation, south‒south cooperation and national sovereignty began to emerge, at least in discourse, from the EU side.

The third project, and I would say the most specific in terms of health cooperation, was the “EU-LAC Health (2011–2017): Roadmap for Cooperative Health Research”. The five-year project is cofunded with the support of the European Community’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013) and was presented on 29 May 2012 by its coordinator, Carlos Segovia, Deputy Director of International Research Programmes and Institutional Relations of the Institute of Health Carlos III (Spain), at the Open Information Day for the 7th call of FP7 Health Theme, as we can see in a press release of the event available online. Among the project partners, we have ISCIII and INNOVATEC (Spain), RIMAIS (Costa Rica), COHRED (Switzerland/Mexico), DLR (Germany), FIOCRUZ (Brazil), MINCyT (Argentina), and APRE (Italy).

According to its website [ 18 ], the EU-LAC Health is a project aimed at defining a Roadmap to support cooperative Health Research. A key aspect of the project will include linking and coordinating two important policy areas: science and technology policy (research) and international development cooperation. The EU-LAC Health is to be implemented through 6 different thematic areas: State of Play Analysis, Operational Road-mapping, Roadmap Consultation, Public Presentation, Final Dissemination and Management.

In November 2012, the project launched the first newsletter with main outcomes from the project activities, which, by that time, were basically an expert workshop held in Fiocruz (Brazil) and another one called ‘Scenario Building Workshop’ held in Buenos Aires, “in order to sort possibilities for a common funding of biregional research cooperation initiatives” and to prepare for the second one, to be held in Italy in 2013 [ 19 ]. Other newsletters were published over time, always indicating future activities.

We also have a kind of evaluation published in 2018: funded by the project and authored by researchers from Spain, Italy, Germany and Brazil who have participated in all activities of the project, already in the abstract we read that “EU-LAC Health represents a successful example of biregional collaboration and the emerging networks and expertise gathered during the lifetime of the project have the potential to tackle common health challenges affecting the quality of life of citizens from the two regions and beyond” ([ 41 ]:1). Although they were not independent actors but participants of the project, we can say that these are experts working in research and national health institutions. Among the main outcomes, the first is the EU-LAC Health Strategic Roadmap [ 17 ] which, according to the authors, “the methodology used for its definition is sound, the procedures have been tested, and the areas of common interest have been demonstrated to be of interest for R&I funding agencies and researchers. Those arguments make the roadmap a useful guide for policy-makers interested in biregional R&I collaboration” (op cit:7).

The Roadmap has seven sections: Context, Vision and Mission, Objectives and Principles, Swot Analysis, Scientific Research Agenda, Governance, and Roadmap Timeline 2015–2020. The authors detail what has been done in each of the six thematic areas mentioned above, relating to the main goals previously set. Other outputs cited in the publication were a network for collaboration among scientists, policy-makers and R&I funding agencies and the establishment of a coordinating body for future EU-LAC collaboration in health R&I.

Multilateral engagement: EU-LAC support of the Oslo Group resolutions approved in the UN General Assembly (2008–2020)

The Foreign Policy and Global Health Initiative (FPGHI) was launched in NY in September 2006. In March 2007, the Ministers of Foreign Affairs of Brazil, France, Indonesia, Norway, Senegal, South Africa, and Thailand issued the "Oslo Ministerial Declaration—Global Health: a pressing foreign policy issue of our time" [ 27 ]. Since 2008, every year the Oslo Group, which is how the FPGHI became known, approves a resolution at the UN General Assembly (UNGA). After mapping the EU-LAC engagement, as sponsors and/or supporters, in each of the thirteen UNGA resolutions (until 2020), Footnote 6 in addition to analyzing six Ministerial Communiqués, we have three resolutions that present the highest engagement among countries of both regions:

2009, A/RES/64/108, about reinforcing the interdependence between foreign policy and global health to coordinate efforts against the H1N1 pandemic throughout local, regional and global levels;

2010, A/RES/65/95, about considering Universal Health Coverage a central factor for the social determinants of health;

2012, A/RES/67/81, about financing mechanisms for enlarging systems of Universal Health Coverage (UHC).

The Oslo Declaration, by its turn, has an agenda organized around three main themes: ‘Capacity for global health security’; ‘Facing threats to global health security’; ‘Making globalization work for all’. The first theme has three specific actions: preparedness to respond to health risks and threats, control of infectious diseases, and strengthening human resources for health. The second theme has four specific actions, all related to conflicts, threats and natural disasters. The third theme has three specific actions, which are development, trade policies and measures to implement and monitor agreements, and improve governance for health. According to these findings regarding the UNGA resolutions, it is possible to say that the EU-LAC cooperation is potentially more effective within the scope of the third theme, which actions reflect the focus on development and trade.

For what we have seen until the COVID-19 pandemic, projects on interregional cooperation, such as EUROsociAL/Salud, COPOLAD and EU-LAC Health, approached different dimensions within a pattern of development through health that is part of a revisionist behavior adopted by both partners, although by different means, throughout the cooperation process. Revisionist behavior, as stated in the introduction, is likely to be seen in longstanding relations among actors with power asymmetry. It is therefore a behavior through which political coordination does not undermine respective interests, preferences, instruments and worldviews that may be different and non-negotiable. Social cohesion and health equity, technical assistance and political dialog on drug policies, and strengthening of health R&I collaboration are goals that represent the politics of cooperation, that is, the common denominators which encompass what each partner expected from the projects. Social development is indeed the premise of consensus-building between policymakers in both regions, through which they achieve significant outputs for global governance for health. In many regards, these projects reflect what is agreed upon in UNGA resolutions, especially in their social dimensions, such as the emphasis on social determinants of health and the enlargement of public systems of UHC.

Therefore, we can say that until the COVID-19 pandemic, the EU-CELAC health cooperation has characterized an approach of development through health within a two-way revisionist behavior embedded in those projects. And that, in practice, the projects were aligned with their multilateral engagement in the UN and in declarations for the occasion of EU-LAC summits over the period. Despite expected disagreements likely emerging out of their essential differences and asymmetries, both regions recognized potential issue areas in which a constructive dialog and policy-oriented outputs were reached. Foreign policy and multidimensional cooperation, embracing from local farmers to academics, have historically favored interregional governance for health. In the next section, I analyze whether and how this has changed since COVID-19.

After the COVID-19 pandemic: any changes?

The first important move occurred after the pandemic came from the EU and, as we will see, affected the CELAC through some changes in the partnership itself. By the end of 2021, in a political response to the pandemic, the European Commission and the EU High Representative have set out the Global Gateway, a new European foreign policy strategy. As regards the budget, “between 2021 and 2027, Team Europe, meaning the EU institutions and EU Member States jointly, will mobilize up to €300 billion of investments for sustainable and high-quality projects, taking into account the needs of partner countries and ensuring lasting benefits for local communities”. It is also expected that the strategy will “create opportunities for the EU Member States’ private sector to invest and remain competitive, while ensuring the highest environmental and labor standards, as well as sound financial management” (Global Gateway website) [ 15 ].

Before exposing what is at the core of EU expectations for health, it is important to say more about the Team Europe approach, as it is the group responsible for allocating the budget and sizing the implementation of the Global Gateway strategy. In the website “Team Europe approach: leadership, cooperation, resources”, we find that Team Europe consists of the European Union, EU Member States — including their implementing agencies and public development banks — as well as the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). It offers a joint programming tracker with an overview on Team Europe Initiatives (TEIs) by country and region in which we see that thus far, for the LAC region, health is not yet contemplated (Team Europe Initiatives and Joint Programming Tracker website [ 29 ]) despite being one among the five key areas (digital sector, climate and energy, transport, health, education and research) selected under the Global Gateway for the EU-CELAC partnership from 2021.

Returning to EU expectations for health within the Global Gateway, we have a summary provided by the DG for International Partnerships in its website:

“Global Gateway will prioritize the security of pharmaceutical supply chains and the development of local manufacturing. Footnote 7 (…) However, health issues extend beyond the pandemic. Thus, the Global Gateway will also facilitate investment in infrastructure and the regulatory environment for the local production of medicine and medical technologies. This will help integrate fragmented markets and promote research and cross-border innovation in healthcare, helping us to overcome diseases such as COVID-19, malaria, yellow fever, tuberculosis or HIV/AIDS” (DG for International Partnerships website).

In addition to this summary, we also have an [ 16 ], which starts by saying “The first two essential priorities are: investing in the well-being of all people and reaching universal health coverage with stronger health systems. The third core priority is combatting current and future health threats, which also requires a new focus. It calls for enhanced equity in the access to vaccines and other countermeasures,for a One Health approach , Footnote 8 which tackles the complex interconnection between humanity, climate, environment and animals” [ 16 ]:6). In the report, we have an agenda leading up to 2030 with three policy priorities—“2.1. Deliver better health and well-being of people across the life course; 2.2. Strengthen health systems and advance universal health coverage; 2.3. Prevent and combat health threats, including pandemics, applying a One Health approach -, provides for twenty guiding principles to shape global health, makes concrete lines of action that operationalize those principles, and creates a new monitoring framework to assess effectiveness and impact of EU policies and funding Footnote 9 ” (op cit:8).

The EU understands itself as having a unique potential to drive international cooperation, expand partnerships and promote health sovereignty “for more resilience and open strategic autonomy supported by partners’ political commitment and responsibility” (op cit:6). Therefore, which kind of changes in EU-CELAC interregional cooperation in health pushed by the Global Gateway and EU Global Health Strategy 2022 can we expect? It seems that this is not an easy question and requires a careful analysis of the documents and speeches mobilized thus far. I propose some ideas in this regard: on the one hand, it is notable that the second policy priority (‘strengthen health systems and advance universal health coverage’) Footnote 10 recovers the Oslo Group resolutions in which the EU and CELAC have reached more consensus and support, in addition to being in line with the two main joint programmes of the past, EUROsociAL/Salud and EU-LAC Health.

On the other hand, with regard to the third policy priority ("prevent and combat health threats, including pandemics, by applying a One Health approach"), it could be interpreted as the novelty promoted by the COVID-19 pandemic, although in reality, only the mention of the ‘One Health approach’ constitutes an innovation. This can be evidenced, for instance, in the 2009 UNGA resolution approved by the Oslo Group, in which the H1N1 pandemic was the target underpinning necessity to ‘coordinate efforts to prevent and combat health threats in local, regional and global levels’. In the same way, other diseases that are long-standing health threats dealt within the EU-CELAC interregional cooperation since at least 2005, such as malaria, yellow fever, tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS, are also mentioned in the Global Gateway for continuing cross-border research and innovation. Therefore, at least in terms of language, of the way ideas are presented and discourses are written, I do not see a stark turnaround. Even so, can we still expect change?

Looking deeper at the EU Global Health Strategy

In the report, each policy priority is developed through guiding principles. When we zoom in on guiding principles of the second policy priority, we see what I just mentioned before: at least in the way they are stated, they remain aligned with the path of EU-CELAC interregional cooperation in health to date, characterized by a pattern of development through health. For this reason, I focus on the third policy priority to explore subsidies for us to reflect upon the following question: should we analyze this interregional partnership in health from 2022 onward in light of a revisionist behavior characterized by ‘reviewing previous disagreements’ or a reformist behavior identified by ‘setting new priorities’? To what extent could it be said that the pattern of cooperation has changed?

Having a closer look at the third priority, ‘Prevent and combat health threats, including pandemics, applying a One Health approach’, we find guiding principles 7 to 11:

GP 7: Strengthen capacities for prevention, preparedness and response and early detection of health threats globally;

GP 8: work toward a permanent global mechanism that fosters the development of and equitable access to vaccines and countermeasures for low- and middle-income countries;

GP 9: negotiate an effective legally binding pandemic agreement with a One Health approach and strengthened International Health Regulations;

GP 10: build a robust global collaborative surveillance network to better detect and act on pathogens;

GP 11: apply a comprehensive One Health approach and intensify the fight against antimicrobial resistance.

To answer the above questions, I will base myself on these guiding principles and add what we have to date: since the EU published the report, three initiatives with CELAC have been announced by the Directorate-General for International Partnerships within the framework of the EU Global Gateway. They are:

22 June 2022: “EU-Latin America and Caribbean Partnership on manufacturing vaccines, medicines and health technologies and strengthening health systems” [ 7 ];

21 March 2023: “EU – Latin America and Caribbean high-level pharmaceutical forum to promote local manufacturing”;

17 July 2023: “EU builds new partnership for improved Latin American and Caribbean health technologies with Pan American Health Organization” [ 8 ].

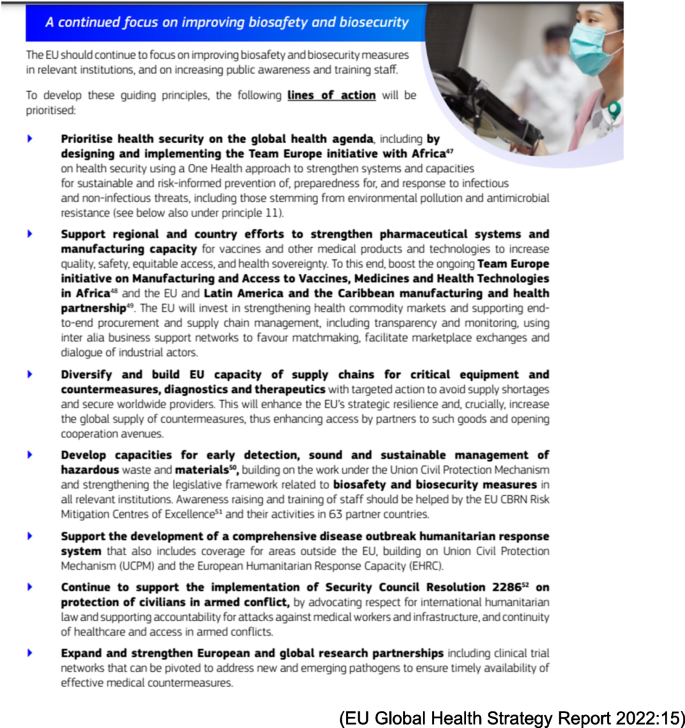

As we can see, all of them are placed within GP 7, which is part of seven lines of action. I reproduce such lines in the figure below.

Regarding the first initiative (‘EU-LAC Partnership on manufacturing vaccines, medicines and health technologies and strengthening health systems’), which seems to be the most robust, we read in the EU communication that it “will complement and further enhance social, economic and scientific ties between the two regions. It will boost Latin America's manufacturing capacity, foster equitable access to quality, effective, safe and affordable health products and help strengthen health resilience in the region to tackle endemic and emerging diseases, and enhance capacities to cope with noncommunicable diseases” (DG for International Partnerships website, News Communication section).

The second initiative (‘EU-LAC high-level pharmaceutical forum to promote local manufacturing’) is a development of the first. The Commissioner for International Partnerships Jutta Urpilainen and Commissioner for Internal Market Thierry Breton hosted in Brussels the EU-LAC High-level Forum Sharing pharmaceutical innovations under the Global Gateway [ 6 ]. Political leaders, technical experts, pharmaceutical companies, entrepreneurs, investors, and financing institutions from both regions were brought together to explore collaboration, for instance, in effective and affordable pharmaceutical innovations (DG for International Partnerships website, Conferences and Summits section).

The third initiative (‘EU builds new partnership for improved LAC health technologies with PAHO’) emerged from the EU-CELAC Summit held on 17 and 18 July 2023 Footnote 11 and was also a development of the first initiative. Ms. Urpilainen and Director of Health Systems and Services of the Pan American Health Organisation (PAHO), Dr James Fitzgerald signed a €3,8 million agreement building a partnership to strengthen LAC access to healthcare technology. The contribution agreement supports the main objectives of the EU-LAC partnership on health, launched by Ms. von der Leyen and Mr. Sánchez in June 2022 (first initiative listed). It focuses in particular on strengthening regulatory frameworks, technology transfers and increasing manufacturing capacities. Footnote 12

After the Summit, an EU-CELAC Roadmap for 2023 to 2025 [ 14 ] indicated that a High-Level event on “Health Regulatory Frameworks” is planned for November 2023, and meetings on Health Self-sufficiency involving regulatory authorities from both regions are planned for 2024–2025. Finally, in the Declaration of the EU-CELAC Summit [ 4 ], we read on paragraph 30, page 8:

“We express our commitment to take forward the biregional partnership on local manufacturing of vaccines, medicines, and other health technologies, and strengthening health systems resilience to improve prevention, preparedness, and response to public health emergencies, in support of the CELAC Plan on Health Self-Sufficiency [see the link to access the Plan in footnote 6]. We look forward to the progress of the ongoing discussions on a new legally binding instrument on pandemic prevention, preparedness, and response in the framework of the World Health Organization, with the aim to agree it by May 2024”.

Taking these primary sources and empirical examples as references for our analysis, the research indicates that the kind of changes in EU-CELAC interregional cooperation in health reflects the dominance of EU interests. Considering the material produced from the EU Global Gateway strategy, launched after the COVID-19 pandemic, until the last EU-CELAC Summit, we can see that the main pattern of interregional cooperation moved from development through health to the current economy-driven health development – a movement clearly propelled by the EU by means of elevating health technologies and manufacturing as priorities despite knowing the enormous structural differences between both regions in this regard.

First and foremost, health technologies and manufacturing in CELAC are mainly conducted with public investment and in public institutions, while in the EU, this field is dominated by big pharma —private transnational companies, among the most profitable and richest in the world, that also count on EU subsidies (Polish Polpharma is a good example Footnote 13 ) and normative facilities. However, in cooperation with CELAC, the centralization of the involvement of the private sector and the International Finance Corporation (IFC), as well as the harmonization of the economic interests in the health sector of several EU Member States, do not seem to be easy tasks for EU foreign policy to effectively implement this change of priorities declared in the official post pandemic documents and in the projects already underway.

With regard to the question of whether this political change on the EU side indicates revisionist or reformist behavior, i.e., a review of previous divergences or an attempt to establish new priorities, a qualitative evaluation of the primary sources from a historical perspective allows me to affirm that we are witnessing a reformist behavior on the part of the EU in its interregional cooperation with CELAC in the area of health. However, it is important to remember that, at the time of writing, the first initiatives have not yet been implemented, and therefore, we still have to wait to empirically evaluate the impacts of such change. We cannot anticipate reactions, contestations or resistance, but we do have lessons learned from the path of EU-LAC partnership in health issues that add valuable insights to our analysis, especially on how the historical differences in terms of health approaches between the two regions have been negotiated. In the next section, I give some of these insights, focusing on the issue of manufacturing pharmaceuticals and health technologies.

Making sense of the EU-LAC Health Partnership within the EU Global Gateway (2021–2027)

To analyze potential points of disagreement at the implementation level of cooperation in manufacturing pharmaceuticals and health technologies, I take into consideration previous disputes involving the EU and CELAC countries located at the intersection between the regimes of health, trade and intellectual property rights (IPR). The EU-Brazil dispute over global access to medicines, which formally started in 2009 within the WTO, is illustrative. On the one hand, the EU focuses on the protection of patents within the IIPR regime and on combating counterfeit drugs, advocating that the defense of IPR and patent law are necessary conditions for investment in the research and technology of medicines conducted in developed countries, which guarantees global health by exporting ‘safe’ medicines worldwide. On the other hand, Brazil sees the EU drawing upon its bargaining power through trade and political leverage to validate its own regulation above multilateral ones at stake, such as the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health (2001), hampering the transit of generics.

Under the EU Regulation 1383/2003 and in response to complaints of patent rights owners, Dutch customs authorities systematically confiscated in transit medicines between 2008–2009 at the Rotterdam port and Schiphol airport in Amsterdam, mainly from India to Africa and Latin America [ 46 ]:25, where the author gives a complete explanation about drug confiscations in European routes), alleging counterfeit and the violation of IPR contained in the WTO TRIPS Agreement (Trade-related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, 1994). For the first time, in early December 2008, Brazil and the EU reached the peak of their divergent perspectives about the right to health vs. IPR regulated by TRIPS. The dispute broke out: on 3 February 2009, the Permanent Representative of Brazil to the WTO Ambassador Roberto Azevedo made an intervention at the WTO General Council (GC) on the seizure by Dutch authorities of a cargo of 570 kilos of losartan potassium docked in Rotterdam while in transit from India to Brazil [ 24 ].

Ambassador Azevedo set one leading point of Brazilian argumentation: the distinction between generics and counterfeit (“ The concept of generic must not be mistaken with counterfeit or pirated. Generic medicines are not substandard or illegal” ), reaffirming the irrelevance of patent law in the Netherlands, which was only the country of transit, supported by the principle of territoriality that is at the basis of the IPR regime ( “Whether or not the medicines were generic under the law of the country of transit is an irrelevant question” ). The dispute lasted until 2016, when the EC (Taxation and Customs Union) published a Commission notice in its website [ 10 ], informing that a new regulation concerning customs enforcement of IPR has replaced the EU Regulation 1383/2003, addressing the “specific concerns raised by India and Brazil on medicines in genuine transit through the EU which are covered by a patent right in the EU”. In an interview given in 2017, Celso Amorim, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Brazil from 2003–2010, summarized the dispute: “We have a very important IP system, one of the most developed IP institutes in the developing world, which gives expertise to other countries. So no, we’re not against IP at all. However, we have to see that life is above profit, and health is above patents” [ 25 ].

This is just one illustrative case, among other disputes between the EU and counterparties such as India, African and LAC countries that are well documented in different UN stages, such as the Intergovernmental Working Group for establishing a legally binding agreement on Business and Human Rights settled within the Human Rights Council in 2014 and the Dispute Settlement Body of the World Trade Organization [ 32 , 59 ]. The EU has consistently acted in the best interest of its pharma companies, and this behavior has been denounced by international NGOs such as Health Action International (2018, [ 23 ]) and Oxfam, as we can see in a press release published in April 2023 on its website under the title “EU pharma legislation ‘total hypocrisy’ while undermining health in poorer countries, campaign says” [ 28 ]. In addition, those NGOs and other researchers from the South [ 34 , 40 , 43 , 44 ] have been systematically reporting that EU trade agreements contain TRIPS + , which are basically additional measures to strengthen IPR also upon health products in detriment of health safeguards regulated by the Doha Declaration of 2001 (see the Doctors Without Borders Access Campaign to further information on EU´s use of TRIPS + in its trade agreements) [ 9 ]. Recently, we have witnessed this concern in regard to the EU-Mercosur FTA [ 38 ].

The second line of action of guiding principle 7 in the [ 16 ], as stated in Fig. 1 , is worth recalling:

“Support regional and country efforts to strengthen pharmaceutical systems and manufacturing capacity for vaccines and other medical products and technologies to increase quality, safety, equitable access, and health sovereignty. To this end, boost the ongoing Team Europe initiative on Manufacturing and Access to Vaccines, Medicines and Health Technologies in Africa and the EU and Latin America and the Caribbean manufacturing and health partnership. The EU will invest in strengthening health commodity markets and supporting end-to-end procurement and supply chain management, including transparency and monitoring, using inter alia business support networks to favor matchmaking, facilitate marketplace exchanges and dialog of industrial actors” (emphasis in the original).

Lines of action driving also guiding principle 7