Learning Styles Debunked: There is No Evidence Supporting Auditory and Visual Learning, Psychologists Say

- Auditory Perception

- Child Development

- Cognitive Psychology

- Learning Styles

- Methodology

- Psychological Science in the Public Interest

- Visual Perception

Are you a verbal learner or a visual learner? Chances are, you’ve pegged yourself or your children as either one or the other and rely on study techniques that suit your individual learning needs. And you’re not alone— for more than 30 years, the notion that teaching methods should match a student’s particular learning style has exerted a powerful influence on education. The long-standing popularity of the learning styles movement has in turn created a thriving commercial market amongst researchers, educators, and the general public.

The wide appeal of the idea that some students will learn better when material is presented visually and that others will learn better when the material is presented verbally, or even in some other way, is evident in the vast number of learning-style tests and teaching guides available for purchase and used in schools. But does scientific research really support the existence of different learning styles, or the hypothesis that people learn better when taught in a way that matches their own unique style?

Unfortunately, the answer is no, according to a major report published in Psychological Science in the Public Interest , a journal of the Association for Psychological Science. The report, authored by a team of eminent researchers in the psychology of learning—Hal Pashler (University of San Diego), Mark McDaniel (Washington University in St. Louis), Doug Rohrer (University of South Florida), and Robert Bjork (University of California, Los Angeles)—reviews the existing literature on learning styles and finds that although numerous studies have purported to show the existence of different kinds of learners (such as “auditory learners” and “visual learners”), those studies have not used the type of randomized research designs that would make their findings credible.

Nearly all of the studies that purport to provide evidence for learning styles fail to satisfy key criteria for scientific validity. Any experiment designed to test the learning-styles hypothesis would need to classify learners into categories and then randomly assign the learners to use one of several different learning methods, and the participants would need to take the same test at the end of the experiment. If there is truth to the idea that learning styles and teaching styles should mesh, then learners with a given style, say visual-spatial, should learn better with instruction that meshes with that style. The authors found that of the very large number of studies claiming to support the learning-styles hypothesis, very few used this type of research design. Of those that did, some provided evidence flatly contradictory to this meshing hypothesis, and the few findings in line with the meshing idea did not assess popular learning-style schemes.

No less than 71 different models of learning styles have been proposed over the years. Most have no doubt been created with students’ best interests in mind, and to create more suitable environments for learning. But psychological research has not found that people learn differently, at least not in the ways learning-styles proponents claim. Given the lack of scientific evidence, the authors argue that the currently widespread use of learning-style tests and teaching tools is a wasteful use of limited educational resources.

Could you please direct me to the source material for this? Thank you.

I found the study here: https://www.psychologicalscience.org/journals/pspi/PSPI_9_3.pdf

The study is here: http://www.psychologicalscience.org/journals/pspi/PSPI_9_3.pdf

I doubt a valid study could be created. There are too many variables. I expect we learn by a combination of all inputs. How could a study overcome the issues of quality of the teachers’ presentation, quality of visuals used compared to quality of auditory materials?

Larry, speaking as a statistics student, I’ll propose an answer to the issue of how a “valid study” can be designed. Feel free to call me out if there is an inherent flaw with my proposal.

I will be referring to American students specifically since this is an issue debated for the American school system. I assume the author is talking about the same thing, but I’ll admit I don’t know if this teaching idea is prevalent in other countries. For the sake of this argument, it really doesn’t matter anyways as this variable is easily changed.

The sample is the most difficult part here, I expect there to be a lot of chosen students who’s parents do not wish their children to be a part of the study for some reason or another. It would also have to be conducted locally, or over a short period of time, though doing it locally would have a greater chance of acceptance among chosen participants. The greatest effort should be made to account for demographics, but, again, this would be difficult. (^Not a great way to start, apologies, but I’m sure a seasoned statistician could come up with the solution that I’m afraid I can’t)

Now, you have your grouping of students, say 1,500 for a reasonable number that would provide relatively a relatively small margin of error. Split each of these students into groups of 500, and assign them to a 25 student-per-teacher classroom that each taught only through auditory, visual, or “hands-on” learning. The students are specifically instructed not to take notes. For this example, let’s say they are learning the properties of liquids. The visual classes are taught through packets that each student is given. The “hands-on” class is given a sheet instructing them how to perform a lab and giving them blanks to fill in. Obviously, for this one, a teacher will tell them how to properly handle equipment and said equipment will be protected against the children hurting themselves inadvertently.(ie, no bunsen burners, but maybe a low-heat burner with students only able to turn it on/off and not touch the hot surface) The hearing group will be given a lecture on the subject, with questions being allowed afterward. After a few days learning this way, every student in every class would be given the same test. Then they would all switch, this time learning about the properties of a solid through the same methods, before being tested on it. Lastly, they would switch to learning and testing on the properties of a gas. As a control, through the same selection process, 500 students could be selected to be taught using all three of the described methods in the same timeframe. That is, instead of a packet, a lecture, or a lab, they could receive a lecture while being shown a powerpoint, followed by a lab.

To prevent previous learning bias, I would suggest all students in the sampling population be the same age, while having not received formal education prior. Also, every student should be taught to use the equipment before the experiment so that the “hands-on” group wouldn’t be at an initial disadvantage.

I’m not a teacher, a psychologist, or a professional statistician. This is just my proposal using my current knowledge of statistics. Take it with a grain of salt and form your own opinions, this is simply being put forth in the effort to show that such an experiment seems to be viable given the proper infrastructure and coordination.

Of course, your method makes sense, but it borders on unethical because it is wrong to teach a child anything in a way that they will not understand. I’m not saying you are unethical, but that any scheme that teaches inappropriately (“don’t take notes”) for more than 5 minutes is unethical.

What a bunch of arrogant people to think that they know if there exists one learning style…!? The only learning style we know is the one in our head. How can you say that there is no other creative ways of learning? What about Autistic people? What about Blind people? What about Deaf people? And Bipolar people? And what about Dyslexic people? And people who have a part of verbal speech comprehensions damages in their brain???? Why give so much importance to a little psychology paper? Any body can do a 3 year psychology degree and then write a paper claiming blabla bla

That’s not what they’re saying at all. They’re saying that there are no categories, or boxes, that people can be put in based on their learning style. They’re not saying there is just one way to learn. No need to get so worked up. People with damage to specific parts of their brains or sensory organs are obviously the outlier. Obviously they are going to be radically different.

And publishing a paper in an esteemed journal takes a _little_ bit more than a 3 year BSc in psychology. It’s that comment that really reveales the depth of your ignorance.

As someone diagnosed with high-functioning autism and currently in a concurrent education course, it is much more dangerous to tell someone they should be okay with only learning in one way rather than teaching them to be flexible and learn to absorb information from all sorts of mediums. So I’m gonna assume you’re blind, dyslexic, and autistic because you’ve assumed you can speak for all of them, yes? Your example of someone being blind also helps to further disprove learning theory — which implies nature over nurture — because clearly the ‘visual’ learners who are rendered blind must learn to learn in a different way (which statistically is shown to affect their learning no differently).

…SOMEBODY doesn’t at all understand the scientific method, reasoning or science in general.

I hope that we can finally move past these always dubious “sensory” learning styles. They’re really “modes,” different ways of learning. I’ve long argued that anyone who feels weak at using any of them needs to practice using that mode more, not less. But another old branch of learning styles based on differing neurotransmitter biases seemed to have better prospects, even if I’ve seen little done with it for decades now. I hope we don’t toss out the entire learning style baby with the dirty “sensory style” bathwater. With our updated technology, we could probably go much farther with it. For background, see dated and rather poorly written but better reasoned explanatory work by Jane Gear.

“I’ve long argued that anyone who feels weak at using any of them needs to practice using that mode more, not less.” As a kid already struggling through school with learning disabilities and the resulting long term stress and exhaustion the last thing I needed was to make things more difficult.

Allow me to state categorically that there are learning styles of which to speak specific to learners. To get the issue on hand, the methods proposed by these researchers as a way to disregard the widespread validity or to invalidate the validity of learning proclivities as a concept is not only inapposite, but also akin to saying that every learner approaches the universe of learning in the exact same way. If that is the measure of what we are to agree on as what constitutes scientific efficacy on any issue, then all forms of research are mitigatable and a suspect in the sense of their nature, methods, outcomes, and overall usefulness.

Such a view to research pieces is clearly misguided, ill-informed and half-scientific … even from a commonsense perspective. It serves no social and scientific utility, but for the interest of the investigators.

Mind you, we are not referring to the efficacy of styles presumptive of or correlative to bettering grade acquisition; rather that it should be argued that there are humane, less torturous, comfortable, less arduous and even naturalistic way of teaching students by emphasizing their uniquely preferred styles, wherever determinable.

Even where indeterminable, instructors are to be encouraged to vary their teaching methods to accommodate the learning needs of their captive audience, in this case, their students, and especially not to think that students learn essentially in the very same way as, for example, their instructors.

To think that all learners learn the same way whether in styles or approaches and to even suppose that instruction is a form of a “straight-jacket” and should work with all “body sizes” is in itself a form of miseducation, misrepresentation and,or a type of stiff recalcitrance that should not ever conduce to the mind of an educator, much less a group of psychologists.

Conbach and Snow’s [in the 60’s] work on learning differences, along with findings affecting Trait/Factor analysis are some of few materials that may well serve as enviable pivots for the current exchange.

When it comes to research concerning learning styles…the human dynamics of learning is so complex that attempting to isolate independent variables that may affect learning is like trying to determine the direction of an automobile by studying petroleum chemistry.

The big problem of understanding this is that people don’t focus on the clear and precise language being used, and don’t understand how experimental science works.

What is being said is that “learning styles” theories which denote specific “auditory” and “visual” learning styles do not have any scientific evidence for them. Those who are evaluated to be predominantly “auditory” in terms of a “learning style” do not in fact perform better or differently when taught “visually” and vice versa.

This is important, because while it seems intuitively true that some people might learn better with a specific medium, there is no evidence for it. What there is evidence for is the superiority of multi-modal or multi-media instruction, in terms of learning outcomes.

The main point is don’t waste time on something that has no evidence to support it. See a ranking of effect size on educational reforms to see what is most important, and what is least: https://visible-learning.org/hattie-ranking-influences-effect-sizes-learning-achievement/

I am currently studying to be an ESL teacher and have come across these “learning styles” with in the course. I do have a rather concerning view about them.

I can see that many minds are put behind how we are going to teach and get the “message” across to learners, but sadly i feel like there is an overdose of ego on “who has the better way to teach”. I know that’s a pretty heavy assumption but i can’t conclude much else except maybe there is a fear that the future generation may not learn correctly, which if this is the case, this manifests into over thinking techniques and deviding the way how individuals learn. I do however believe that segregating ways in which people learn is crazy and an over analysed attempt.

As i was studying this i couldn’t help but scrunch my nose in confusion when alot of the individual “learning styles” were something that i have as a “whole” and as an “individual”. I strongly believe that everything works hand in hand.

If i was to simply hold up a picture of someone playing golf and not attach a word or action to it, they would simply know what it looks like but not know what to call it or how it works. Auditory and kinaesthetic would be eliminated and the student will be deprived. But what concerns me is, that i would be compelled to put action to something like this(in a teachers mind) and tell them what we call it (golf). So to be segregating “learning styles” you must be going against a law within your conscience as to how we ALL “learn” this seriously is a no brainer for me.

I must say though not everything is based on science, simply using your brain can solve many of complications. I say that encouragingly not as a rivalry. Hope this was helpful.

Teaching golf would integrate all 4 learning styles. Why not use kinesthetic methods to complement visual, auditory, and logical when appropriate?

Howdy folks! I’d like to understand this a little better. So these guys invalidated all of the studies because they didn’t meet their standard and for that reason they declare that everyone has the same learning style? Is that what they are saying? I don’t see that they setup and carried out a scientific study that meets their own criteria to prove their hypothesis that we all the same learning style. Did I miss something there? Let’s just say the science wasn’t good enough as they say, then that only means that the science hasn’t proved anything. If the science isn’t good enough to prove it right…. then I’m thinking that it doesn’t prove it wrong either. Wouldn’t that just mean that the hypothesis just remains unproven? I wonder too if someone can explain what learning style I’m using when I’m learning how to play my drums? So I’m trying to learn a double stroke roll and feeling the stick bounce and snapping my fingers and wrist at the right moment… it’s all about the feel. To me that’s my kinesthetic learning channel. I’m programming my “muscle memory” is yet another frame for explaining it. Does their conclusion invalidate this learning channel? When it comes to learning songs, I listen by sound. I listen and repeat. I have friends who can only play along with sheet music. They read and play. I didn’t carry out a study to figure this out. I just talk to other drummers and there’s clearly 2 sets of learning styles right there. Many drummers can only sight read. I can’t. I ask then… how is this possible if we all have the same learning style? And the argument is that we should stop wasting money trying to make education better? Really? I think I’ll disengage my gullible learning style and turn on my critical thinking style. …or does that not exist either?

You have to learn to read sheet music , just like reading a book. but it takes effort and once you learn it is good. learning by ear is more natural and maybe you will be more creative because music is audio. The Beatles could not read music. They seem to be saying it has not been determined if audio or visual leaning styles exist. Not whether one is better than the other and if we don’t know if they exist then why spend money behind them. You could invent many other plausible teaching methods and theories and spend a lot of money but maybe the best money spent is on things we know make a difference.

I dont what most people in here are even talking about. Scientific research? In the end it comes down to enjoyment.

The individual is as diverse from one another both in appearance and behaviours. It is not been proven that learning styles are debunked, only that on review by some eminent scientists, a shadow of doubt challenges the premise. Thus if we are diverse creatures it follows we will take in the world in diverse ways, some of us will have more developed auditory facilities, some hardwiring may mean visuals are easier – this is not a study but a fact. We as humans do everything differently than others, perhaps the universal categories should not be bandied about carelessly. But in education in particular, we certainly do take our world in in many and varied forms, construct how we see it and enact a life we see fit, all embedded in our social environment

I was encouraged that the psychologists got put in their place by those of us(teachers) who understand that all children learn differently. Why would you want to frustrate any child with visual learning material that leads to nothing but failure, when the same child can find success with teaching methods that match the child’s learning style?

Byron Thorne author of Toward A Failure-Proof Methodology for Learning To Read.

I love the article and the follow up debate. As a long time educator and student of education it is positive to see all the different perspectives. How to make things manageable for learners? Multi-modal presentations with options for showing one’s understanding and learning. Any teaching can be presented in various ways concurrently as long as we give the students what they need to have access to. My question would be more about how to best engage students so they would be engaged and self-motivated. Love the conversation.

I don’t agree or believe you! I am a visual and auditory learner. It works for me! I was a teacher and everyone has preferred learning styles. Some people do better with a snack. Some are tactile. Your study may be flawed but your conclusions are wrong.c Nance

They can say what they like, but I have seen very different foci in various individuals, with the same-system adherants failing miserably, more often than not, relative to more flexible instructors. I myself cannot grasp complex ideas without first having, or mentally generating, a visual reference.

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines .

Please login with your APS account to comment.

Teaching: Successive Relearning / Thriving After Psychopathology

Lesson plans about successive relearning and finding happiness after being diagnosed with a mental disorder.

Pursuing Best Practices in STEM Education: The Peril and Promise of Active Learning

Active learning is a promising yet loosely defined STEM instructional technique.

Natural Selection: The Mentoring Edition

In today’s society they may be hidden, but good shepherds do exist. They nurture. They guide. They use their foresight to keep their flock safe and ensure its survival. As graduate students, we often find

Privacy Overview

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __cf_bm | 30 minutes | This cookie, set by Cloudflare, is used to support Cloudflare Bot Management. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| AWSELBCORS | 5 minutes | This cookie is used by Elastic Load Balancing from Amazon Web Services to effectively balance load on the servers. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| at-rand | never | AddThis sets this cookie to track page visits, sources of traffic and share counts. |

| CONSENT | 2 years | YouTube sets this cookie via embedded youtube-videos and registers anonymous statistical data. |

| uvc | 1 year 27 days | Set by addthis.com to determine the usage of addthis.com service. |

| _ga | 2 years | The _ga cookie, installed by Google Analytics, calculates visitor, session and campaign data and also keeps track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookie stores information anonymously and assigns a randomly generated number to recognize unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_3507334_1 | 1 minute | Set by Google to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | Installed by Google Analytics, _gid cookie stores information on how visitors use a website, while also creating an analytics report of the website's performance. Some of the data that are collected include the number of visitors, their source, and the pages they visit anonymously. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| loc | 1 year 27 days | AddThis sets this geolocation cookie to help understand the location of users who share the information. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | A cookie set by YouTube to measure bandwidth that determines whether the user gets the new or old player interface. |

| YSC | session | YSC cookie is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos on Youtube pages. |

| yt-remote-connected-devices | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt-remote-device-id | never | YouTube sets this cookie to store the video preferences of the user using embedded YouTube video. |

| yt.innertube::nextId | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

| yt.innertube::requests | never | This cookie, set by YouTube, registers a unique ID to store data on what videos from YouTube the user has seen. |

- Teaching Methods

- Learning Styles

Learning styles and the human brain: what does the evidence tell us?

- September 2019

- CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

- This person is not on ResearchGate, or hasn't claimed this research yet.

- Autonomous University of Coahuila

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

No file available

To read the file of this research, you can request a copy directly from the authors.

- Meghan L. Meyer

- Diana I. Tamir

- Eva H. Telzer

- María G Leyva-Cruz

- Flérida Moreno-Alcaraz

- Nat. Hum. Behav.

- Beatrice Farb

- Elizabeth Huber

- Patrick M. Donnelly

- Yunyun Duan

- Heidi Johansen-Berg

- Theor Res Educ

- Bryan L. Dawson

- Shelly R. Cooper

- Todd S. Braver

- Michael A. Skeide

- Falk Huettig

- SOC COGN AFFECT NEUR

- Hao-Ting Wang

- Mahallad Miah

- Christina B. Young

- R. Douglas Fields

- Akira Miyake

- David M. Bashwiner

- Katie L. Tropiano

- Achille Pasqualotto

- Alan Maclachlan

- Andrew M. Lothian

- John Sweller

- Carol Westby

- Peter E. Turkeltaub

- Michael T. Ullman

- COMPUT EDUC

- PERS INDIV DIFFER

- Reid L. Skeel

- K. Roger Van Horn

- DJ PITTENGER

- Marcus E. Raichle

- Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic

- Sophie von Stumm

- Scott O. Lilienfeld

- John Ruscio

- Barry L. Beyerstein

- NAT REV NEUROSCI

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Key facts about Americans and guns

Guns are deeply ingrained in American society and the nation’s political debates.

The Second Amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees the right to bear arms, and about a third of U.S. adults say they personally own a gun. At the same time, in response to concerns such as rising gun death rates and mass shootings , the U.S. surgeon general has taken the unprecedented step of declaring gun violence a public health crisis .

Here are some key findings about Americans’ views of gun ownership, gun policy and other subjects, drawn from Pew Research Center surveys.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to summarize key facts about Americans’ relationships with guns. We used data from recent Center surveys to provide insights into Americans’ views on gun policy and how those views have changed over time, as well as to examine the proportion of adults who own guns and their reasons for doing so.

The Center survey questions used in this analysis, and more information about the surveys’ methodologies, and can be found at the links in the text.

Measuring gun ownership in the United States comes with unique challenges. Unlike many demographic measures, there is not a definitive data source from the government or elsewhere on how many American adults own guns.

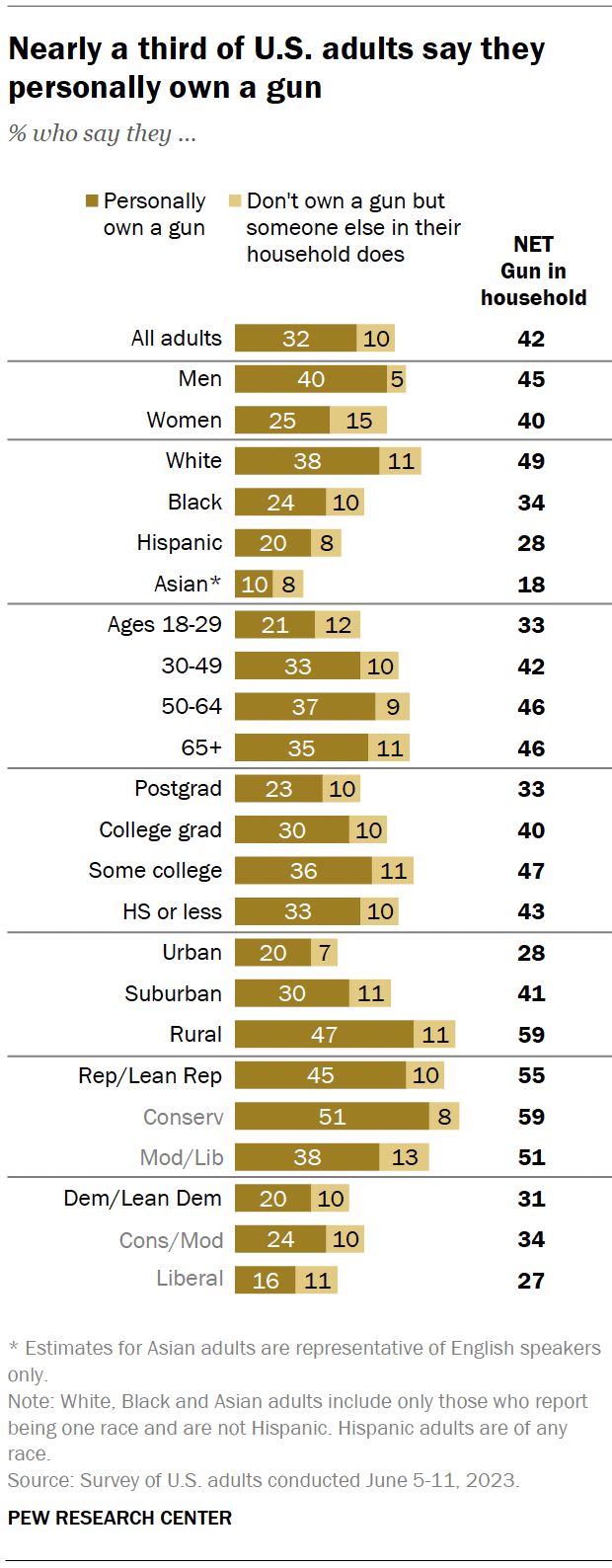

The Pew Research Center survey conducted June 5-11, 2023, on the Center’s American Trends Panel, used two separate questions to measure personal and household ownership. About a third of adults (32%) say they own a gun, while another 10% say they do not personally own a gun but someone else in their household does. These shares have changed little from surveys conducted in 2021 and 2017 . In each of those surveys, 30% reported they owned a gun.

These numbers are largely consistent with rates of gun ownership reported by Gallup and those reported by NORC’s General Social Survey .

The FBI maintains data on background checks on individuals attempting to purchase firearms in the United States. The FBI reported a surge in background checks in 2020 and 2021, during the coronavirus pandemic, but FBI statistics show that the number of federal background checks declined in 2022 and 2023. This pattern seems to be continuing so far in 2024. As of June, fewer background checks have been conducted than at the same point in 2023, according to FBI statistics.

About four-in-ten U.S. adults say they live in a household with a gun, including 32% who say they personally own one, according to a Center survey conducted in June 2023 . These numbers are virtually unchanged since the last time we asked this question in 2021.

There are differences in gun ownership rates by political affiliation, gender, community type and other factors.

- Party: 45% of Republicans and GOP-leaning independents say they personally own a gun, compared with 20% of Democrats and Democratic leaners.

- Gender: 40% of men say they own a gun, versus 25% of women.

- Community type: 47% of adults living in rural areas report owning a firearm, as do smaller shares of those who live in suburbs (30%) or urban areas (20%).

- Race and ethnicity: 38% of White Americans own a gun, compared with smaller shares of Black (24%), Hispanic (20%) and Asian (10%) Americans.

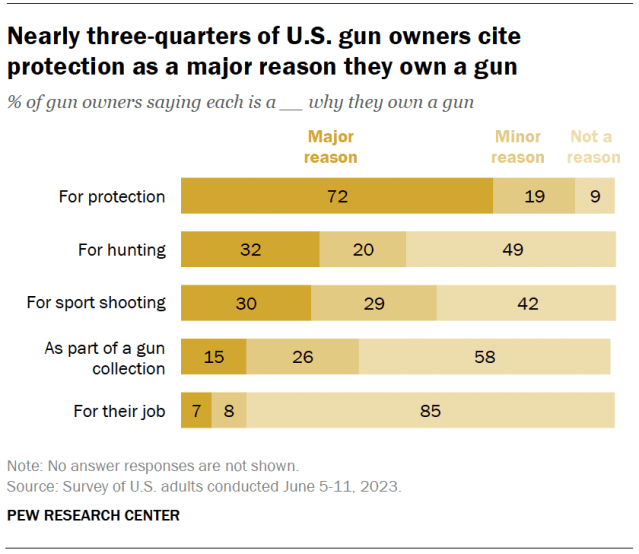

Personal protection tops the list of reasons gun owners give for having a firearm. About seven-in-ten gun owners (72%) say protection is a major reason they own a gun. Considerably smaller shares say that a major reason they own a gun is for hunting (32%), for sport shooting (30%), as part of a gun collection (15%) or for their job (7%).

Americans’ reasons behind gun ownership have changed only modestly since we fielded a separate survey about these topics in spring 2017. At that time, 67% of gun owners cited protection as a major reason they had a firearm.

Gun owners tend to have much more positive feelings about having a gun in the house than nonowners who live with them do. For instance, 71% of gun owners say they enjoy owning a gun – but just 31% of nonowners living in a household with a gun say they enjoy having one in the home. And while 81% of gun owners say owning a gun makes them feel safer, a narrower majority of nonowners in gun households (57%) say the same. Nonowners are also more likely than owners to worry about having a gun at home (27% vs. 12%).

Feelings about gun ownership also differ by political affiliation, even among those who personally own a firearm. Republican gun owners are more likely than Democratic owners to say owning one gives them feelings of safety and enjoyment, while Democratic owners are more likely to say they worry about having a gun in the home.

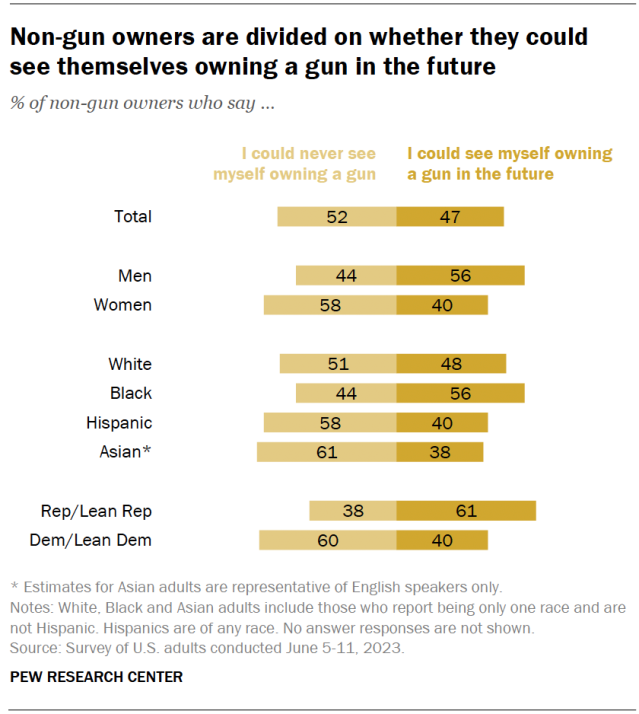

Non-gun owners are split on whether they see themselves owning a firearm in the future. About half of Americans who don’t own a gun (52%) say they could never see themselves owning one, while nearly as many (47%) could imagine themselves as gun owners in the future.

Among those who currently do not own a gun, attitudes about owning one in the future differ by party and other factors.

- Party: 61% of Republicans who don’t own a gun say they could see themselves owning one in the future, compared with 40% of Democrats.

- Gender: 56% of men who don’t own a gun say they could see themselves owning one someday; 40% of women nonowners say the same.

- Race and ethnicity: 56% of Black nonowners say they could see themselves owning a gun one day, compared with smaller shares of White (48%), Hispanic (40%) and Asian (38%) nonowners.

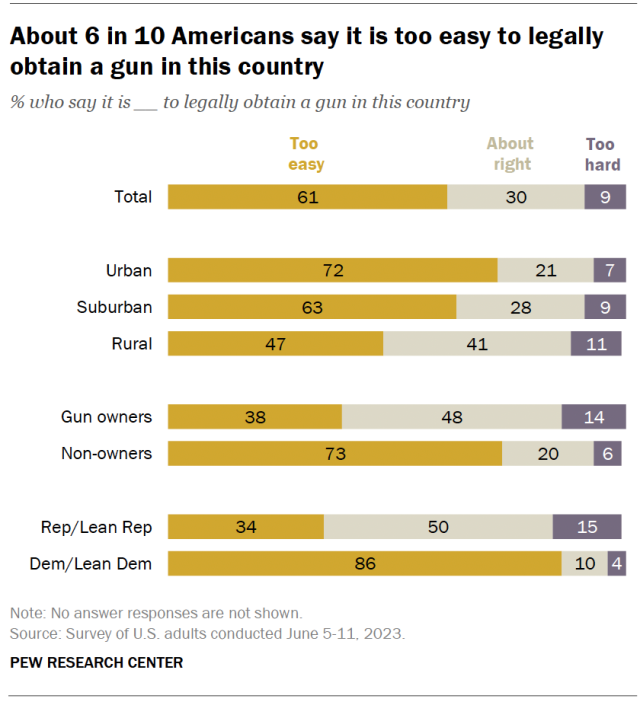

A majority of Americans (61%) say it is too easy to legally obtain a gun in this country, according to the June 2023 survey. Far fewer (9%) say it is too hard, while another 30% say it’s about right.

Non-gun owners are nearly twice as likely as gun owners to say it is too easy to legally obtain a gun (73% vs. 38%). Gun owners, in turn, are more than twice as likely as nonowners to say the ease of obtaining a gun is about right (48% vs. 20%).

There are differences by party and community type on this question, too. While 86% of Democrats say it is too easy to obtain a gun legally, far fewer Republicans (34%) say the same. Most urban (72%) and suburban (63%) residents say it’s too easy to legally obtain a gun, but rural residents are more divided: 47% say it is too easy, 41% say it is about right and 11% say it is too hard.

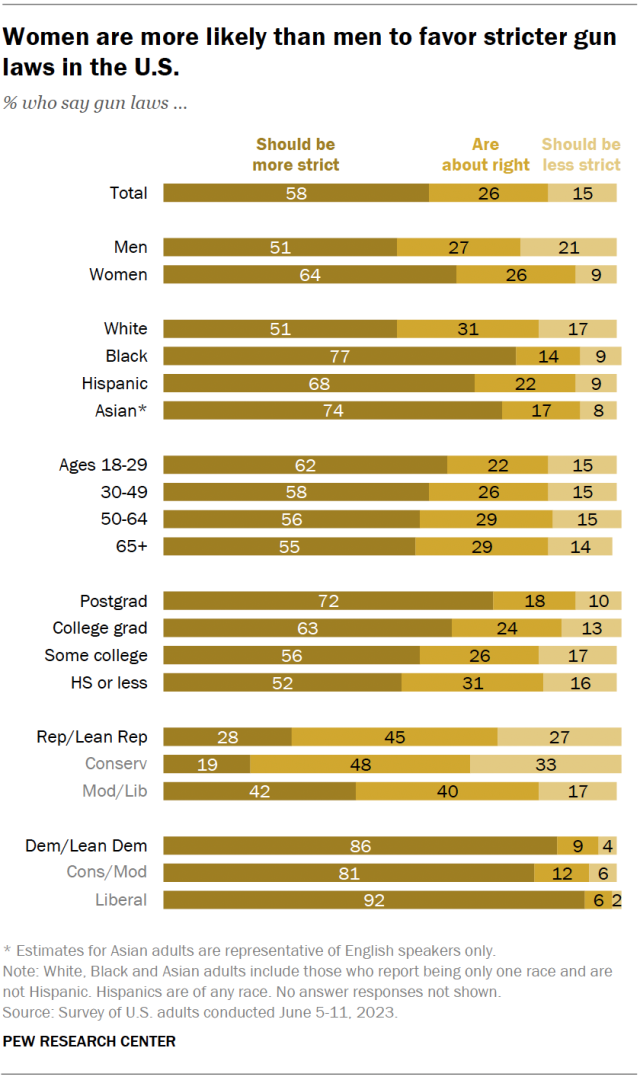

About six-in-ten U.S. adults (58%) favor stricter gun laws. Another 26% say that U.S. gun laws are about right, while 15% favor less strict gun laws.

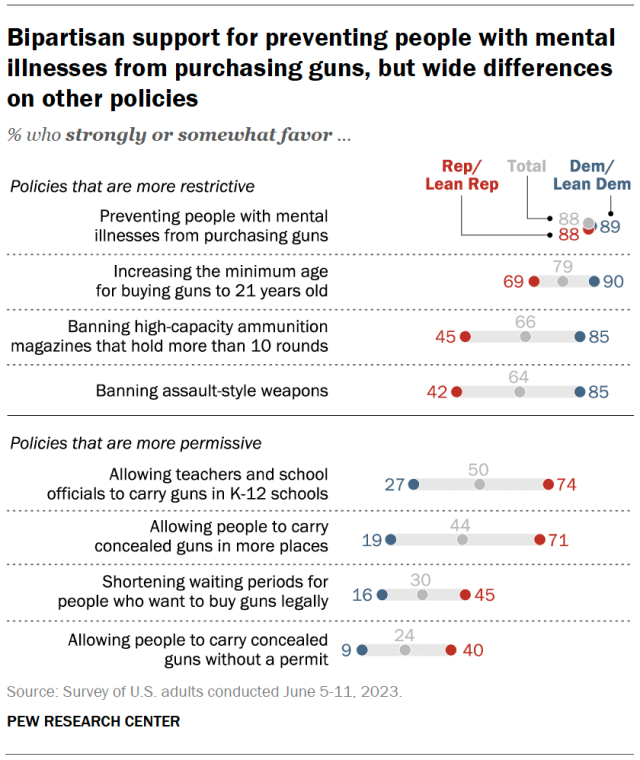

There is broad partisan agreement on some gun policy proposals, but most are politically divisive. Majorities of U.S. adults in both partisan coalitions somewhat or strongly favor two policies that would restrict gun access: preventing those with mental illnesses from purchasing guns (88% of Republicans and 89% of Democrats support this) and increasing the minimum age for buying guns to 21 years old (69% of Republicans, 90% of Democrats). Majorities in both parties also oppose allowing people to carry concealed firearms without a permit (60% of Republicans and 91% of Democrats oppose this).

Republicans and Democrats differ on several other proposals. While 85% of Democrats favor banning both assault-style weapons and high-capacity ammunition magazines that hold more than 10 rounds, majorities of Republicans oppose these proposals (57% and 54%, respectively).

Most Republicans, on the other hand, support allowing teachers and school officials to carry guns in K-12 schools (74%) and allowing people to carry concealed guns in more places (71%). These proposals are supported by just 27% and 19% of Democrats, respectively.

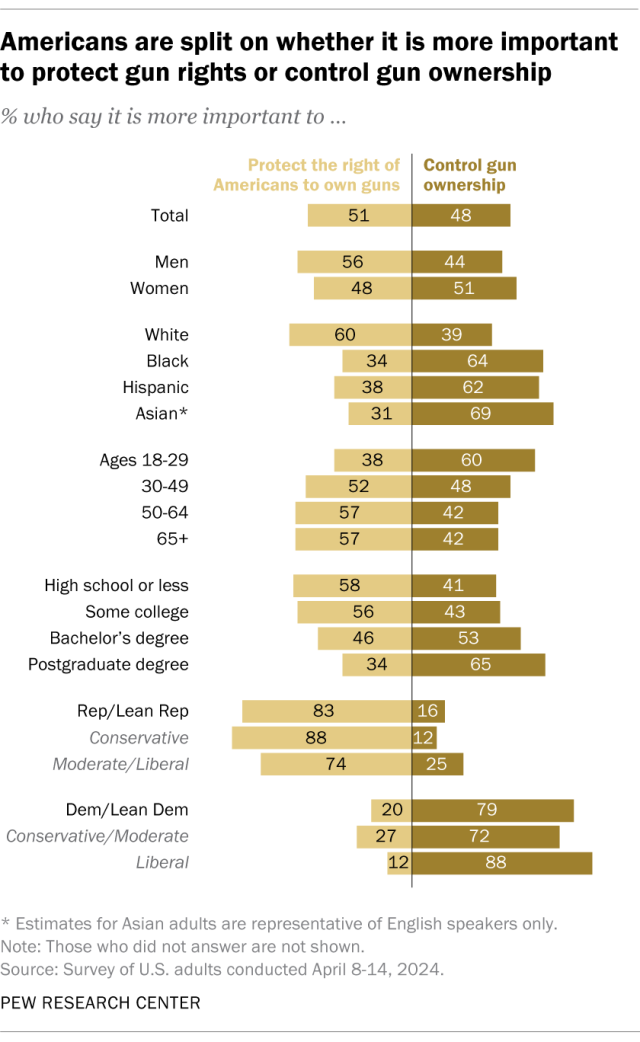

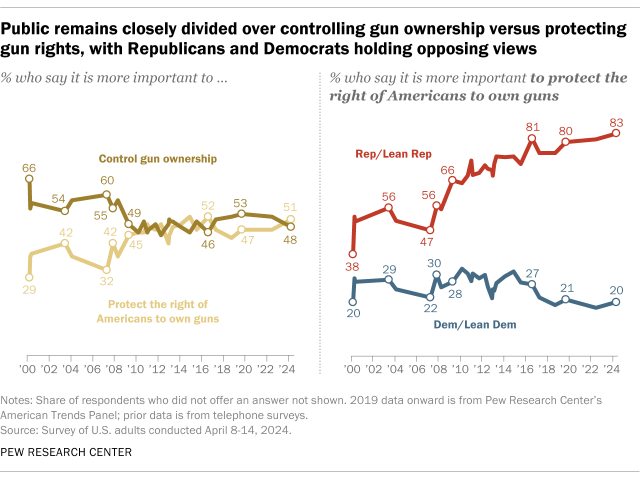

The public remains closely divided over whether it’s more important to protect gun rights or control gun ownership, according to an April 2024 survey . Overall, 51% of U.S. adults say it’s more important to protect the right of Americans to own guns, while a similar share (48%) say controlling gun ownership is more important.

Views have shifted slightly since 2022, when we last asked this question. That year, 47% of adults prioritized protecting Americans’ rights to own guns, while 52% said controlling gun ownership was more important.

Views on this topic differ sharply by party. In the most recent survey, 83% of Republicans say protecting gun rights is more important, while 79% of Democrats prioritize controlling gun ownership.

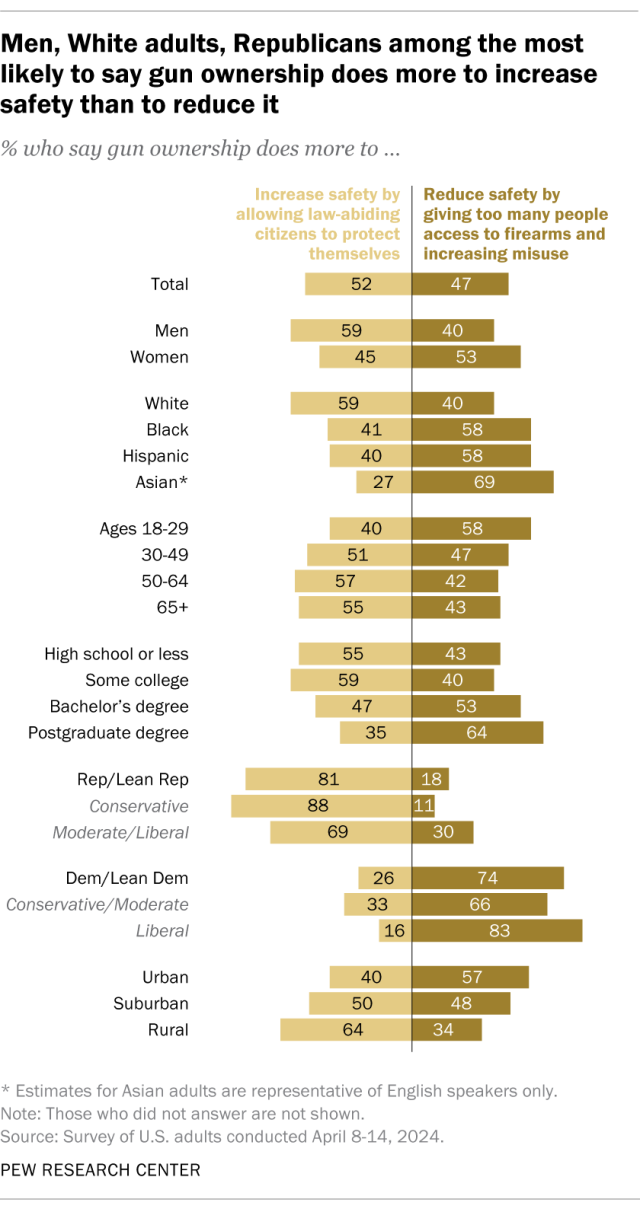

Americans are slightly more likely to say gun ownership does more to increase safety than to decrease it. Around half of Americans (52%) say gun ownership does more to increase safety by allowing law-abiding citizens to protect themselves, while a slightly smaller share (47%) say gun ownership does more to reduce safety by giving too many people access to firearms and increasing misuse. Views were evenly divided (49% vs. 49%) when we last asked in 2023.

Republicans and Democrats differ widely on this question: 81% of Republicans say gun ownership does more to increase safety, while 74% of Democrats say it does more to reduce safety.

Rural and urban Americans also have starkly different views. Among adults who live in rural areas, 64% say gun ownership increases safety, while among those in urban areas, 57% say it reduces safety. Those living in the suburbs are about evenly split in their views.

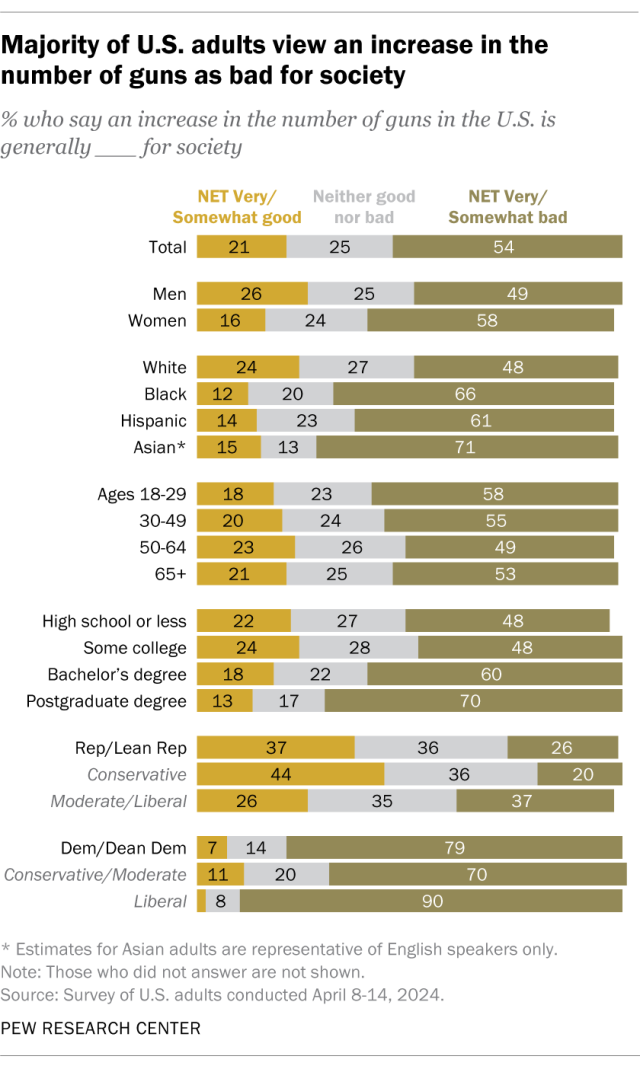

More than half of U.S. adults say an increase in the number of guns in the country is bad for society, according to the April 2024 survey. Some 54% say, generally, this is very or somewhat bad for society. Another 21% say it is very or somewhat good for society, and a quarter say it is neither good nor bad for society.

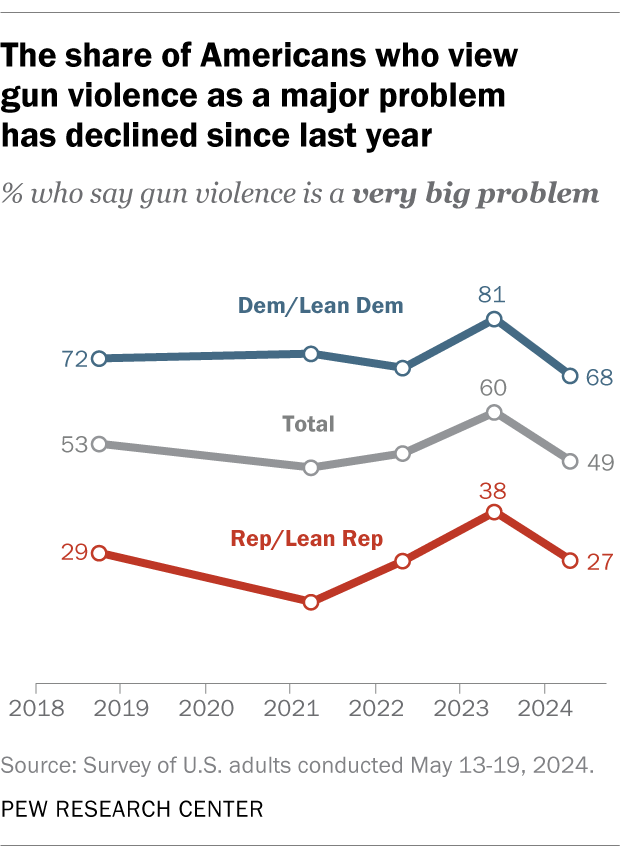

About half of Americans (49%) see gun violence as a major problem, according to a May 2024 survey. This is down from 60% in June 2023, but roughly on par with views in previous years. In the more recent survey, 27% say gun violence is a moderately big problem, and about a quarter say it is either a small problem (19%) or not a problem at all (4%).

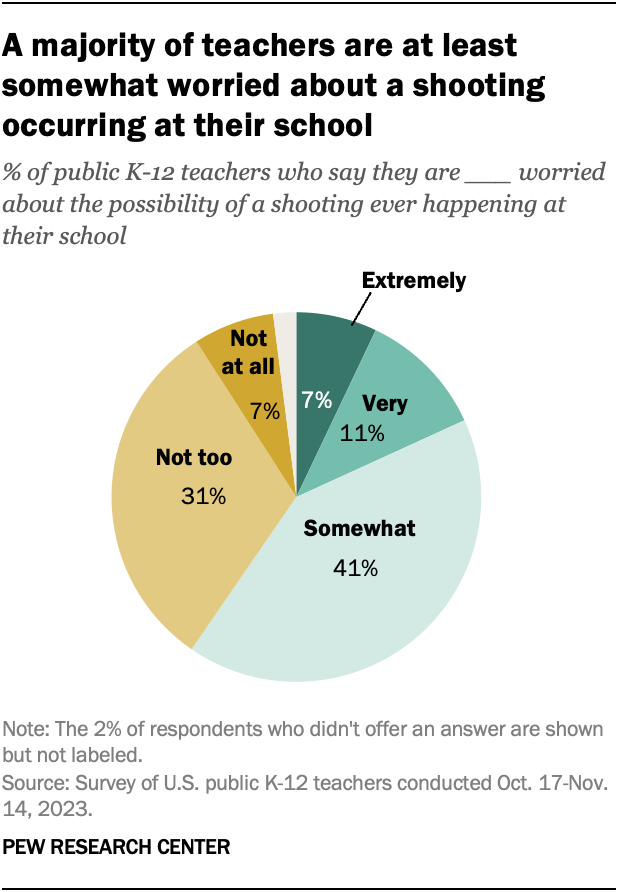

A majority of public K-12 teachers (59%) say they are at least somewhat worried about the possibility of a shooting ever happening at their school, including 18% who are very or extremely worried, according to a fall 2023 Center survey of teachers . A smaller share of teachers (39%) say they are not too or not at all worried about a shooting occurring at their school.

School shootings are a concern for K-12 parents as well: 32% say they are very or extremely worried about a shooting ever happening at their children’s school, while 37% are somewhat worried, according to a fall 2022 Center survey of parents with at least one child younger than 18 who is not homeschooled. Another 31% of K-12 parents say they are not too or not at all worried about this.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published on Jan. 5, 2016 .

- Partisanship & Issues

- Political Issues

Katherine Schaeffer is a research analyst at Pew Research Center .

Views on America’s global role diverge widely by age and party

War in ukraine: wide partisan differences on u.s. responsibility and support, americans’ extreme weather policy views and personal experiences, u.s. adults under 30 have different foreign policy priorities than older adults, many adults in east and southeast asia support free speech, are open to societal change, most popular.

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

The Learning Styles Myth is Thriving in Higher Education

Associated data.

The existence of ‘Learning Styles’ is a common ‘neuromyth’, and their use in all forms of education has been thoroughly and repeatedly discredited in the research literature. However, anecdotal evidence suggests that their use remains widespread. This perspective article is an attempt to understand if and why the myth of Learning Styles persists. I have done this by analyzing the current research literature to capture the picture that an educator would encounter were they to search for “Learning Styles” with the intent of determining whether the research evidence supported their use. The overwhelming majority (89%) of recent research papers, listed in the ERIC and PubMed research databases, implicitly or directly endorse the use of Learning Styles in Higher Education. These papers are dominated by the VAK and Kolb Learning Styles inventories. These presence of these papers in the pedagogical literature demonstrates that an educator, attempting to take an evidence-based approach to education, would be presented with a strong yet misleading message that the use of Learning Styles is endorsed by the current research literature. This has potentially negative consequences for students and for the field of education research.

Introduction

Davies (1999) called for an ‘evidence-based’ approach to education, arguing that the design of new interventions in education was not sufficiently informed by rigorous evidence and that new interventions are then poorly evaluated. Although this was one in a series of such calls, the very idea of evidence-based education continues to be criticized (e.g., see Biesta, 2010 ), often on the basis that education is complex (allegedly more so than medicine, to which it is often compared). For example, what does it mean to say that something has ‘worked’, and for whom has it ‘worked’ and in what context?

Despite this complexity, there are some concepts in education for which there is abundant clear evidence to show that they are not effective. One of these is Learning Styles, such as the ‘VAK’ classification, which classifies individuals as one or more of ‘Visual, Auditory, or Kinesthetic’ learners ( Geake, 2008 ). Other classifications include those by (separately) Kolb, Felder and Honey and Mumford; in total there are over 70 different classification systems ( Coffield et al., 2004 ). The concept of ‘Learning Styles’ as an educational tool is fairly straightforward, and follows three steps: (1) individuals will express a preference regarding their ‘style’ of learning, (2) individuals show differences in their ability to learn about certain types of information (e.g., some may be better at learning to discriminate between sounds while others may be better at discriminating between pictures), and (3) the ‘matching’ of instructional design to an individual’s Learning Style, as designated by one of the aforementioned classifications, will result in better educational outcomes (e.g., visual learners should have information presented visually, while auditory learners would do better with an emphasis on audio).

The utility of step 2 for education is debatable, as most learning is constructed from multiple types of information, and to acquire ‘meaning’ and ‘understanding’ arguably goes beyond a specific sensory domain. However, it is the last step, the ‘matching hypothesis’, where the concept of Learning Styles completely falls down. A comprehensive review by Pashler et al. (2008) determined that there was no evidence to support the use of Learning Styles in education, based upon a lack of evidence to support ‘matching’. Coffield et al. (2004) reviewed the literature pertaining to 71 different Learning Styles classifications, with the aim of answering the question “should we be using them in post-16 education.” The answer was a resounding ‘no’.

The use of an ineffective educational technique is potentially associated with harm – students who are labeled as having a dominant Learning Style (e.g., ‘visual learners’) may then choose not to pursue subjects which they perceive as being dominated by a different learning style (e.g., music), or may develop a false sense of confidence in their abilities to master subjects which they perceive as matching their style. Perhaps most importantly, the use of ineffective techniques such as Learning Styles can detract from the use of techniques which are demonstrably effective ( Riener and Willingham, 2010 ; Willingham et al., 2015 ).

Despite this, amongst educators, there appears to be widespread belief in the use of Learning Styles. A survey by Dekker et al. (2012) showed that 93% of UK schoolteachers believed the (unsupported) statement that “individuals learn better when they receive information in their preferred Learning Style”. Follow-up studies have shown similar results in other countries ( Howard-Jones, 2014 ). A study conducted using faculty in Higher Education in the USA found similar results, with 64% rating ‘yes’ to the statement “does teaching to a student’s learning style enhance learning” ( Dandy and Bendersky, 2014 ). This is reflected at the institutional level – a survey of 39 Higher Education institutions in the US found that 29 of them (72%) taught ‘learning style theory’ as part of faculty development for online teachers ( Meyer and Murrell, 2014 ).

Learning Styles have been designated a ‘neuromyth’ ( Lilienfeld et al., 2011 , p. 92; Dekker et al., 2012 ; Howard-Jones, 2014 ) and the lack of evidence to support them has been the subject of reviews and commentaries ( Riener and Willingham, 2010 ; Rohrer and Pashler, 2012 ; Willingham et al., 2015 ). Alongside this formal literature are blogs and online videos debunking the ‘myth.’ I wrote one myself, motivated, as I am sure others have been, by my personal experience of meeting numerous students and educators who accepted the concept of Learning Styles as an established, textbook principle. However, with the wealth of strong research studies and social media, it seemed reasonable to hypothesize that the use of Learning Styles may now be in decline, and that this would be seen most keenly in the current research literature.

Alternately, Learning Styles may represent the educational equivalent of homeopathy: a medical concept for which no evidence exists, yet in which belief and use persists. There has been a significant body of research aimed at understanding why such beliefs persist, a simple summary of which is that people often seek out information which aligns with their existing worldview, akin to a prospective confirmation bias ( Colombo et al., 2015 ). Confirmation bias has been suggested as one reason why Learning Styles and other myths appear to persist ( Riener and Willingham, 2010 ; Pasquinelli, 2012 ).

Intuitively, there is much that is attractive about the concept of Learning Styles. People are obviously different and Learning Styles appear to offer educators a way to accommodate individual learner differences. They also allow individuals to self-test and determine what ‘type’ of learner they are. These intuitive attractions may ‘set up’ an educator to fall into the trap of confirmation bias – approaching the research literature having already formed a view that Learning Styles are ‘a good thing’. Therefore, I also set out to characterize the picture an educator would encounter were they to search the education research literature for evidence to support, or not, the use of Learning Styles.

Methodology

Two major databases of life sciences/education research were used as the datasets. PubMed is a database of research publications in the life sciences and biomedicine 1 While ERIC (Education Information Resources Center) is ‘an online library of education research and information’ 2

A search of the PubMed database 3 was carried out for the term “learning styles”, with the date range July 23, 2013 to July 23, 2015 (to reflect current research). Only papers studying Higher Education were selected for analysis. The term “learning styles” was also used to search the ERIC database, with results filtered to be positive for the criteria ‘peer reviewed’ and ‘Higher Education’ for 2015, then 2014, then 2013 (July–December).

The analysis was restricted to Higher Education on the basis that (1) one of the most comprehensive reviews regarding the use of Learning Styles in education was focused specifically on post-16 education ( Coffield et al., 2004 ) and (2) a lecturer in Higher Education is normally appointed as a subject-matter expert on the basis of their research expertise, and so would normally be familiar with using research literature.

For every search result, the following questions were asked (further detail below) –

- ◦ Was the study about Learning Styles?

- ◦ Were participants students/staff in Higher Education or beyond?

- ◦ Was the full text in English?

- • What was the specific study population (e.g., medical students)?

- • In which country was the study conducted?

- • What Learning Style(s) was being used or tested?

- • Does the study begin with positive view toward Learning Styles?

- • Does the study conclude with positive view toward Learning Styles?

- • Does the study test the matching hypothesis as put forward by Pashler et al. (2008) ?

- • Do the study results challenge the conclusions of Pashler/Coffield?

This study was aimed at providing a snapshot of the Learning Styles research available to the ‘casual’ inquirer – an academic considering the use of these methods in their teaching. Thus the questions asked were initially of the study abstract. If the answers were clear from the abstract, then the full text was not consulted. If the answers were not clear from the abstract, then the full text was consulted. Only full text papers that were freely available were consulted; if a subscription or payment was required, then the result was not included because access to them would vary considerably between individual educators.

Details about the questions asked:

Was the Study About the Use of Learning Styles?

The term ‘Learning Styles’ was taken to mean of one of the 71 Learning Styles inventories described in Figure 4 of Coffield et al. (2004) . The studies analyzed had to use Learning Styles in a manner which attempted to understand something about student learning (including the training of educators).

Examples of studies which did not meet this criterion included those about ‘learning styles’ rather than ‘Learning Styles’, i.e., they used the term learning styles as a normal grammatical construct or talked in broad terms about ‘learning styles’. For example, an article may discuss the need to ‘accommodate different learning styles’ without it being conclusively clear that this referred to Learning Styles as defined by Coffield et al. (2004) .

What Learning Style is Being Used or Tested?

This was classified using the aforementioned review by Coffield et al. (2004) , with appropriate adaption [e.g., studies using variations on the VAK Learning Styles classification (such as ‘VARK’ and ‘VAKT’) were all grouped together].

Does the Study Begin with Positive View Toward Learning Styles?

Yes - Did the study start with a premise that the use/identification of Learning Styles was a useful aim. This could be implicit (e.g., the premise of the study includes an assumption that it is useful to identify a learner’s Learning Style even if the finding is then that Learning Styles are not effective in that context).

No – The study was setting out to test Learning Styles themselves, e.g., to determine whether their use was valid.

Does the Study Conclude with Positive View Toward Learning Styles?

Yes – The study concluded that the use of Learning Styles was effective for student learning. This again could be implicit – for example, studies where a group of participants are classified using a Learning Styles inventory and the conclusion is then that the dominant Learning Styles in this group are X and Y.

No – The study concluded that the use of Learning Styles by educators was not effective for student learning.

Test Matching?

Did the study test the ‘matching hypothesis’ as described in Pashler et al. (2008) . That is, does matching instruction to a students Learning Style result in improved outcomes?

Contradict Pashler/Coffield

Do the research findings challenge the conclusions drawn by Pashler et al. (2008) and Coffield et al. (2004) ? That is, does the reported evidence support the idea that matching instructional design to individual student Learning Style is effective?

Number of Search Results

The data for search results are shown in Figure Figure1 1 . The ERIC research database returned more results than PubMed, but both demonstrate that an educator conducting a simple search for “learning styles” would be presented with abundant, modern, results, although there is a suggestion that the numbers of studies may be declining in the ERIC database. These data do not necessarily reflect an increase in use of Learning Styles or in Learning Styles research; there may be a concurrent increase in the total number of publications listed in these databases.

Research database search results for the term “Learning Styles” filtered by individual calendar year .

Endorsement of Learning Styles

For ERIC, the initial search for recent papers returned 110 unique results, of which 54 met the inclusion criteria. For PubMed, the initial search returned 126 unique results; 57 of these met the inclusion criteria. ‘Unique results’ refers to results that appeared only once within that database. Two studies were present in both databases and so were excluded from any pooled analysis ( N = 109). The results of the subsequent analysis are shown in Table Table1 1 .

The majority of current research findings in the PubMed and ERIC databases endorse the use of Learning Styles.

| Analysis | All (109) | ERIC (54) | PubMed (57) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive intent | 103 (94%) | 51 (94%) | 54 (95%) |

| Positive outcome | 97 (89%) | 49 (91%) | 50 (85%) |

| Test matching | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Contradict Pashler/Coffield | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Most (94%) of the current research papers start out with a positive view of Learning Styles, despite the aforementioned research which discredits their use. Six papers started out with positive intent, but reached a negative conclusion regarding the use of Learning Styles.

One study, not shown in Table Table1 1 , described testing a ‘matching hypothesis’ and appeared to show that matching had some benefit, but from the data presented it was not clear whether it was truly a matching hypothesis as proposed by Pashler et al. (2008) , or which specific Learning Style inventory was being tested, or how the data were analyzed ( Surjono, 2015 ).

Type of Learning Style

The majority of papers featured a single Learning Style. The Kolb classification accounted for 34% of all papers, while VAK-type classifications accounted for 33%. The Felder–Silverman (and Felder–Soloman) classifications accounted for (12%). Other featured classifications included Vermunt (2 of the 109 studies) Honey and Mumford (itself derived from Kolb) (3), Grasha–Reischmann (4), Myers–Briggs type (4), Biggs Study Process Questionnaire (2), Dunn and Dunn (1), and Gregorc (1). Five publications addressed Learning Styles generally.

Type of Participant

The studies included participants from across a wide variety of disciplines. Notably, for the studies obtained using PubMed, students in health professions programs (medicine, nursing, dentistry, etc.,) dominated, accounting for a total of 53 out of 57 studies (93%).

Country of Origin

The studies represented a total of 29 different countries around the world, with the single biggest contribution coming from the USA (41 studies, 33%) followed by Turkey (10, 8%).

Excluded Studies

Approximately half (125) of the search results were not analyzed. More than half of these (66) were not demonstrably about ‘Learning Styles’, while the full text was not available for 22. Other reasons for exclusion included study populations other than students/teachers in higher education (12), non-English language (6) and the use of ‘Learning Styles’ other than those listed in Coffield et al. (2004) (5).

The data presented here demonstrate that the use of Learning Styles is thriving in Higher Education. This result is somewhat surprising given the rigorous research ( Coffield et al., 2004 ; Pashler et al., 2008 ) demonstrating the ineffectiveness of Learning Styles, alongside an abundance of critical material in social media. The use of Learning Styles may cause harm through ‘pigeon-holing’ and the diversion of resources away from evidence-based practices ( Riener and Willingham, 2010 ; Willingham et al., 2015 ). Why, then, is the recent research literature so overwhelmingly misleading?

The literature on cognitive bias indicates that we will seek, or at least be sympathetic to, information which confirms our existing worldview. Confirmation bias has been suggested as a reason for the success of Learning Styles ( Riener and Willingham, 2010 ; Pasquinelli, 2012 ) and there is much that is attractive about the basic idea of Learning Styles. Thus an educator might reasonably approach the literature with an expectation that Learning Styles are a useful tool. The present study demonstrates that this view would be overwhelmingly confirmed, thus encouraging and perpetuating the use of Learning Styles.

There is another interpretation – if the majority of studies endorse the use of Learning Styles, then maybe Coffield et al. (2004) and Pashler et al. (2008) are wrong? The lack of any evidence base to support the use of Learning Styles was acknowledged by some of the studies found here, despite their overall endorsement of the use of Learning Styles. Some even cite the works of Coffield et al. (2004) , Pashler et al. (2008) , Willingham et al. (2015) , and others. Some engage the literature and defend the use of Learning Styles as identifying ‘learner preferences’ rather than a basis for matching instruction, or as a prompt for students to reflect on how they learn. Overall though, most studies appear generally uncritical – a very common approach is to simply apply a Learning Style classification to a particular type of student, and then make recommendations based upon the findings. These studies do not really engage the aforementioned evidence.

There is an obvious limitation to the findings presented here – a single researcher has analyzed the papers and made a subjective judgment as to whether or not they endorse the use of Learning Styles. This methodology may lack sufficient rigor to be fully endorsed by many advocates of evidence-based education. However, the papers are all in the Supplementary Data Sheet S1 . I approached the analysis with an open mind, half expecting to find an abundance of studies decrying Learning Styles. In the end this was overwhelmingly not the case, and I found it relatively straightforward to decide whether a study endorsed the use of Learning Styles.

Conclusion And Recommendations

Learning Styles do not work, yet the current research literature is full of papers which advocate their use. This undermines education as a research field and likely has a negative impact on students.

If you have got this far in reading this perspective, you likely care about education, and about education research. It is in everyone’s interests for educational research and resources – time, money, effort, to be directed toward those educational interventions which demonstrably improve student learning, and away from those which do not. Take a second to run a Google search on your own institution – put in the domain name – youruniversity.edu or.ac.uk or whatever it is, alongside the term “learning styles”. Chances are, something will come up. Start there!

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1 www.pubmed.com.

2 www.eric.ed.gov.

3 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01908

- Biesta G. J. J. (2010). Why “what works” still won’t work: from evidence-based education to value-based education. Stud. Philos. Educ. 29 491–503. 10.1007/s11217-010-9191-x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Coffield F., Moseley D., Hall E., Ecclestone K. (2004). Learning Styles and Pedagogy in Post 16 Learning: A Systematic and Critical Review. London: Learning and Skills Research Centre. [ Google Scholar ]

- Colombo M., Bucher L., Inbar Y. (2015). Explanatory judgment, moral offense and value-free science. Rev. Philos. Psychol. 1–21. 10.1007/s13164-015-0282-z [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dandy K., Bendersky K. (2014). Student and faculty beliefs about learning in higher education: implications for teaching. Int. J. Teach. Learn. High. Educ. 26 358–380. [ Google Scholar ]

- Davies P. (1999). What is evidence-based education? Br. J. Educ. Stud. 47 108–121. 10.1111/1467-8527.00106 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dekker S., Lee N. C., Howard-Jones P., Jolles J. (2012). Neuromyths in education: prevalence and predictors of misconceptions among teachers. Front. Psychol. 3 : 429 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00429 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Geake J. (2008). Neuromythologies in education. Educ. Res. 50 123–133. 10.1080/00131880802082518 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Howard-Jones P. A. (2014). Neuroscience and education: myths and messages. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 15 817–824. 10.1038/nrn3817 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lilienfeld S. O., Lynn S. J., Ruscio J., Beyerstein B. L. (2011). 50 Great Myths of Popular Psychology: Shattering Widespread Misconceptions about Human Behavior. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons. [ Google Scholar ]

- Meyer K. A., Murrell V. S. (2014). A National Study of Theories and Their Importance for Faculty Development for Online Teaching. Online J. Distance Learn. Adm. 17. Available at: http://www.westga.edu/∼distance/ojdla/summer172/Meyer_Murrell172.html [accessed August 24 2015]. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pashler H., McDaniel M., Rohrer D., Bjork R. (2008). Learning styles: concepts and evidence. Psychol. Sci. Public Interest 9 105–119. 10.1111/j.1539-6053.2009.01038.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pasquinelli E. (2012). Neuromyths: why do they exist and persist? Mind Brain Educ. 6 89–96. 10.1111/j.1751-228X.2012.01141.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Riener C., Willingham D. (2010). The myth of learning styles. Change 42 32–35. 10.1080/00091383.2010.503139 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rohrer D., Pashler H. (2012). Learning styles: where’s the evidence? Med. Educ. 46 634–635. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04273.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Surjono H. D. (2015). The effects of multimedia and learning style on student achievement in online electronics course – ProQuest. Turk. Online J. Educ. Technol. 14 116–122. [ Google Scholar ]

- Willingham D. T., Hughes E. M., Dobolyi D. G. (2015). The scientific status of learning styles theories. Teach. Psychol. 42 266–271. 10.1177/0098628315589505 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

COMMENTS

Over the last two decades, learning styles instruction has become ubiquitous in public education. It has gained influence and has enjoyed wide acceptance among educators at all levels, parents, and the general public (Pashler et al., 2009).It is prevalent in teacher education programs, adult education programs (Bishka, 2010), promoted in k-12 schools in many countries (Scott, 2010), and ...

The authors of the present review were charged with determining whether these practices are supported by scientific evidence. We concluded that any credible validation of learning-styles-based instruction requires robust documentation of a very particular type of experimental finding with several necessary criteria. First, students must be divided into groups on the basis of their learning ...

WASHINGTON — Many people, including educators, believe learning styles are set at birth and predict both academic and career success even though there is no scientific evidence to support this common myth, according to new research published by the American Psychological Association. In two online experiments with 668 participants, more than ...

Recent work suggests that perceived learning styles may be linked to both older children's (i.e., approx. 10-14-years-old) and adults' thinking about their identities (e.g., "I'm a visual ...

LEARNING STYLES. A benchmark definition of "learning styles" is "characteristic cognitive, effective, and psychosocial behaviors that serve as relatively stable indicators of how learners perceive, interact with, and respond to the learning environment. 10 Learning styles are considered by many to be one factor of success in higher education. . Confounding research and, in many instances ...

The Current Study. Given that learning styles-based instruction is most highly targeted to the K-12 environment, coupled with the importance of verbal comprehension on educational outcomes, this study investigated the learning styles hypothesis, specifically as it pertains to the auditory/visual dichotomy in 5th graders.

The term learning styles (LS) describes the notion that individuals have a preferred modality of learning and that presenting to-be-learned material in this modality results in optimal learning for them (Pashler, McDaniel, Rohrer, & Bjork, 2008).To date, studies around the globe suggest that LS is very popular among preservice and in-service teachers, including school principals, student ...

A recent study demonstrated that current research papers 'about' Learning Styles, in the higher education research literature, ... Ninety percent of academics agreed that there is a basic conceptual flaw with Learning Styles Theory. These data suggest that, although there is an ongoing controversy about Learning Styles, their actual use may ...

The common point of learning style definitions is the learner preferences based on personal characteristics and differences. Some learners prefer to learn by reading, some by writing, some by listening, and some by watching. Recognition of learning styles yields positive learning outcomes for both learners and instructors.

The findings highlight the nuanced relationship between learning style preferences, COVID-19 infection experiences, and mental health outcomes among students. ... this study suggests that we ...

Understanding of the Learning Style Myth Shaylene E. Nancekivell, Priti Shah, and Susan A. Gelman University of Michigan Decades of research suggest that learning styles, or the belief that people learn better when they receive instruction in their dominant way of learning, may be one of the most pervasive myths about cognition.

learning styles research and contend that little of that research is linked to cognition or by guest on October 7, 2015 tre.sagepub.com Downloaded from 6 Theory and Research in Education

Riding and Cheema's Fundamental Dimensions. Having identified in excess of 30 labels used to describe a variety of cognitive and learning styles, Riding and Cheema (Citation 1991) propose a broad categorisation of style according to two fundamental dimensions representing the way in which information is processed and represented: wholist-analytic and verbaliser-imager.

The existence of 'Learning Styles' is a common 'neuromyth', and their use in all forms of education has been thoroughly and repeatedly discredited in the research literature. However, anecdotal evidence suggests that their use remains widespread. This perspective article is an attempt to understand if and why the myth of Learning Styles persists.

The current study addresses this issue by examining whether teachers, parents, ... They specifically suggest that many people view learning styles through an essentialist lens6,25.

> Latest Research News > Learning Styles Debunked: ... To prevent previous learning bias, I would suggest all students in the sampling population be the same age, while having not received formal education prior. Also, every student should be taught to use the equipment before the experiment so that the "hands-on" group wouldn't be at an ...

Abstract. Learning Styles (LS) are a very popular idea in Education and Psychology. However, most studies indicate that matching the instructional strategy to the students' LS does not improve ...

This study set out to determine a methodology for estimating learning styles and cognitive traits from LMS access records. In this paper, we presented a model for the automatic identification of learner behavior in LMS records. The model takes advantage of data collected from the LMS log, education theories, and literature-based methods to ...

Current research on learning styles suggests that.. A. teachers should identify each student's learning style and tailor all activities to support that style B. intellectual potential is related to learning style C. there is little or no evidence that certain learning style are associated with particular ethnic groups D. learning styles are ...

An understanding of learning styles. - Enables a teacher to pinpoint individual differences that affect a person's learning. - Assumes that all of us have a capacity to grow and develop. - Allows informed students to become active participants in their own learning. - Can help teachers tune into cultural differences without stereotyping ...

Regardless of the context or modality, a common theme emerges in the literature: the importance of tailoring instruction to the student's learning style. A body of research suggests that by aligning the teaching strategy with the student's preferred learning style, one can enhance student engagement, understanding of material, and ...

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder that affects learning capability and social behavior of people. Over the past few decades, awareness regarding ASD has increased ...

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like Current research on whether students can be identified has having specific "learning styles" suggests that teachers should: A. ask the students to say what their learning styles are and then allow them to choose activities to match. B. assess each student's learning style and provide learning activities that match it. C. adapt ...

About four-in-ten U.S. adults say they live in a household with a gun, including 32% who say they personally own one, according to a Center survey conducted in June 2023.These numbers are virtually unchanged since the last time we asked this question in 2021. There are differences in gun ownership rates by political affiliation, gender, community type and other factors.

The ability of students to adapt to various situations for their learning needs will result in high learning outcomes. 20-23 An additional benefit of learning style research is that policymakers can consider other factors related to learning and teaching, such as curriculum design, materials development, student orientation, and teacher ...

The existence of 'Learning Styles' is a common 'neuromyth', and their use in all forms of education has been thoroughly and repeatedly discredited in the research literature. However, anecdotal evidence suggests that their use remains widespread. This perspective article is an attempt to understand if and why the myth of Learning Styles ...