ARTS - Herzberg: Writing Essays About Art

- Art History

- Current Artists and Events

- Local Art Venues

- Video and Image Resources

- Writing Essays About Art

- Citation Help

What is a Compare and Contrast Essay?

What is a compare / contrast essay.

In Art History and Appreciation, contrast / compare essays allow us to examine the features of two or more artworks.

- Comparison -- points out similarities in the two artworks

- Contrast -- points out the differences in the two artworks

Why would you want to write this type of essay?

- To inform your reader about characteristics of each art piece.

- To show a relationship between different works of art.

- To give your reader an insight into the process of artistic invention.

- Use your assignment sheet from your class to find specific characteristics that your professor wants you to compare.

How is Writing a Compare / Contrast Essay in Art History Different from Other Subjects?

You should use art vocabulary to describe your subjects..

- Find art terms in your textbook or an art glossary or dictionary

You should have an image of the works you are writing about in front of you while you are writing your essay.

- The images should be of high enough quality that you can see the small details of the works.

- You will use them when describing visual details of each art work.

Works of art are highly influenced by the culture, historical time period and movement in which they were created.

- You should gather information about these BEFORE you start writing your essay.

If you describe a characteristic of one piece of art, you must describe how the OTHER piece of art treats that characteristic.

Example: You are comparing a Greek amphora with a sculpture from the Tang Dynasty in China.

If you point out that the color palette of the amphora is limited to black, white and red, you must also write about the colors used in the horse sculpture.

Organizing Your Essay

Thesis statement.

The thesis for a comparison/contrast essay will present the subjects under consideration and indicate whether the focus will be on their similarities, on their differences, or both.

Thesis example using the amphora and horse sculpture -- Differences:

While they are both made from clay, the Greek amphora and the Tang Dynasty horse served completely different functions in their respective cultures.

Thesis example -- Similarities:

Ancient Greek and Tang Dynasty ceramics have more in common than most people realize.

Thesis example -- Both:

The Greek amphora and the Tang Dynasty horse were used in different ways in different parts of the world, but they have similarities that may not be apparent to the casual viewer.

Visualizing a Compare & Contrast Essay:

Introduction (1-2 paragraphs) .

- Creates interest in your essay

- Introduces the two art works that you will be comparing.

- States your thesis, which mentions the art works you are considering and may indicate whether the focus will be on similarities, differences, or both.

Body paragraphs

- Make and explain a point about the first subject and then about the second subject

- Example: While both superheroes fight crime, their motivation is vastly different. Superman is an idealist, who fights for justice …… while Batman is out for vengeance.

Conclusion (1-2 paragraphs)

- Provides a satisfying finish

- Leaves your reader with a strong final impression.

Downloadable Essay Guide

- How to Write a Compare and Contrast Essay in Art History Downloadable version of the description on this LibGuide.

Questions to Ask Yourself After You Have Finished Your Essay

- Are all the important points of comparison or contrast included and explained in enough detail?

- Have you addressed all points that your professor specified in your assignment?

- Do you use transitions to connect your arguments so that your essay flows into a coherent whole, rather than just a random collection of statements?

- Do your arguments support your thesis statement?

Art Terminology

- British National Gallery: Art Glossary Includes entries on artists, art movements, techniques, etc.

Lee College Writing Center

Writing Center tutors can help you with any writing assignment for any class from the time you receive the assignment instructions until you turn it in, including:

- Brainstorming ideas

- MLA / APA formats

- Grammar and paragraph unity

- Thesis statements

- Second set of eyes before turning in

Contact a tutor:

- Phone: 281-425-6534

- Email: w [email protected]

- Schedule a web appointment: https://lee.mywconline.com/

Other Compare / Contrast Writing Resources

- Southwestern University Guide for Writing About Art This easy to follow guide explains the basic of writing an art history paper.

- Purdue Online Writing Center: writing essays in art history Describes how to write an art history Compare and Contrast paper.

- Stanford University: a brief guide to writing in art history See page 24 of this document for an explanation of how to write a compare and contrast essay in art history.

- Duke University: writing about paintings Downloadable handout provides an overview of areas you should cover when you write about paintings, including a list of questions your essay should answer.

- << Previous: Video and Image Resources

- Next: Citation Help >>

- Last Updated: Jun 26, 2024 1:51 PM

- URL: https://lee.libguides.com/Arts_Herzberg

Art History

What this handout is about.

This handout discusses a few common assignments found in art history courses. To help you better understand those assignments, this handout highlights key strategies for approaching and analyzing visual materials.

Writing in art history

Evaluating and writing about visual material uses many of the same analytical skills that you have learned from other fields, such as history or literature. In art history, however, you will be asked to gather your evidence from close observations of objects or images. Beyond painting, photography, and sculpture, you may be asked to write about posters, illustrations, coins, and other materials.

Even though art historians study a wide range of materials, there are a few prevalent assignments that show up throughout the field. Some of these assignments (and the writing strategies used to tackle them) are also used in other disciplines. In fact, you may use some of the approaches below to write about visual sources in classics, anthropology, and religious studies, to name a few examples.

This handout describes three basic assignment types and explains how you might approach writing for your art history class.Your assignment prompt can often be an important step in understanding your course’s approach to visual materials and meeting its specific expectations. Start by reading the prompt carefully, and see our handout on understanding assignments for some tips and tricks.

Three types of assignments are discussed below:

- Visual analysis essays

- Comparison essays

- Research papers

1. Visual analysis essays

Visual analysis essays often consist of two components. First, they include a thorough description of the selected object or image based on your observations. This description will serve as your “evidence” moving forward. Second, they include an interpretation or argument that is built on and defended by this visual evidence.

Formal analysis is one of the primary ways to develop your observations. Performing a formal analysis requires describing the “formal” qualities of the object or image that you are describing (“formal” here means “related to the form of the image,” not “fancy” or “please, wear a tuxedo”). Formal elements include everything from the overall composition to the use of line, color, and shape. This process often involves careful observations and critical questions about what you see.

Pre-writing: observations and note-taking

To assist you in this process, the chart below categorizes some of the most common formal elements. It also provides a few questions to get you thinking.

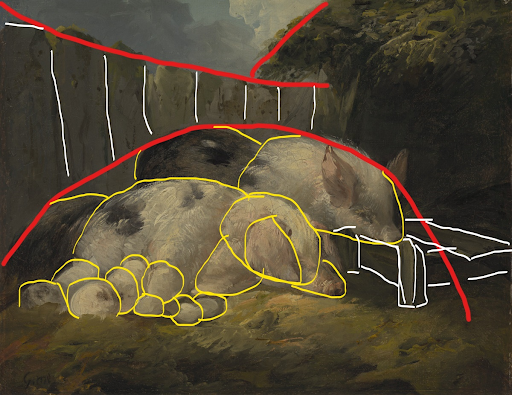

Let’s try this out with an example. You’ve been asked to write a formal analysis of the painting, George Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty , ca. 1800 (created in Britain and now in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond).

What do you notice when you see this image? First, you might observe that this is a painting. Next, you might ask yourself some of the following questions: what kind of paint was used, and what was it painted on? How has the artist applied the paint? What does the scene depict, and what kinds of figures (an art-historical term that generally refers to humans) or animals are present? What makes these animals similar or different? How are they arranged? What colors are used in this painting? Are there any colors that pop out or contrast with the others? What might the artist have been trying to accomplish by adding certain details?

What other questions come to mind while examining this work? What kinds of topics come up in class when you discuss paintings like this one? Consider using your class experiences as a model for your own description! This process can be lengthy, so expect to spend some time observing the artwork and brainstorming.

Here is an example of some of the notes one might take while viewing Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty :

Composition

- The animals, four pigs total, form a gently sloping mound in the center of the painting.

- The upward mound of animals contrasts with the downward curve of the wooden fence.

- The gentle light, coming from the upper-left corner, emphasizes the animals in the center. The rest of the scene is more dimly lit.

- The composition is asymmetrical but balanced. The fence is balanced by the bush on the right side of the painting, and the sow with piglets is balanced by the pig whose head rests in the trough.

- Throughout the composition, the colors are generally muted and rather limited. Yellows, greens, and pinks dominate the foreground, with dull browns and blues in the background.

- Cool colors appear in the background, and warm colors appear in the foreground, which makes the foreground more prominent.

- Large areas of white with occasional touches of soft pink focus attention on the pigs.

- The paint is applied very loosely, meaning the brushstrokes don’t describe objects with exact details but instead suggest them with broad gestures.

- The ground has few details and appears almost abstract.

- The piglets emerge from a series of broad, almost indistinct, circular strokes.

- The painting contrasts angular lines and rectangles (some vertical, some diagonal) with the circular forms of the pig.

- The negative space created from the intersection of the fence and the bush forms a wide, inverted triangle that points downward. The point directs viewers’ attention back to the pigs.

Because these observations can be difficult to notice by simply looking at a painting, art history instructors sometimes encourage students to sketch the work that they’re describing. The image below shows how a sketch can reveal important details about the composition and shapes.

Writing: developing an interpretation

Once you have your descriptive information ready, you can begin to think critically about what the information in your notes might imply. What are the effects of the formal elements? How do these elements influence your interpretation of the object?

Your interpretation does not need to be earth-shatteringly innovative, but it should put forward an argument with which someone else could reasonably disagree. In other words, you should work on developing a strong analytical thesis about the meaning, significance, or effect of the visual material that you’ve described. For more help in crafting a strong argument, see our Thesis Statements handout .

For example, based on the notes above, you might draft the following thesis statement:

In Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty, the close proximity of the pigs to each other–evident in the way Morland has overlapped the pigs’ bodies and grouped them together into a gently sloping mound–and the soft atmosphere that surrounds them hints at the tranquility of their humble farm lives.

Or, you could make an argument about one specific formal element:

In Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty, the sharp contrast between rectilinear, often vertical, shapes and circular masses focuses viewers’ attention on the pigs, who seem undisturbed by their enclosure.

Support your claims

Your thesis statement should be defended by directly referencing the formal elements of the artwork. Try writing with enough specificity that someone who has not seen the work could imagine what it looks like. If you are struggling to find a certain term, try using this online art dictionary: Tate’s Glossary of Art Terms .

Your body paragraphs should explain how the elements work together to create an overall effect. Avoid listing the elements. Instead, explain how they support your analysis.

As an example, the following body paragraph illustrates this process using Morland’s painting:

Morland achieves tranquility not only by grouping animals closely but also by using light and shadow carefully. Light streams into the foreground through an overcast sky, in effect dappling the pigs and the greenery that encircles them while cloaking much of the surrounding scene. Diffuse and soft, the light creates gentle gradations of tone across pigs’ bodies rather than sharp contrasts of highlights and shadows. By modulating the light in such subtle ways, Morland evokes a quiet, even contemplative mood that matches the restful faces of the napping pigs.

This example paragraph follows the 5-step process outlined in our handout on paragraphs . The paragraph begins by stating the main idea, in this case that the artist creates a tranquil scene through the use of light and shadow. The following two sentences provide evidence for that idea. Because art historians value sophisticated descriptions, these sentences include evocative verbs (e.g., “streams,” “dappling,” “encircles”) and adjectives (e.g., “overcast,” “diffuse,” “sharp”) to create a mental picture of the artwork in readers’ minds. The last sentence ties these observations together to make a larger point about the relationship between formal elements and subject matter.

There are usually different arguments that you could make by looking at the same image. You might even find a way to combine these statements!

Remember, however you interpret the visual material (for example, that the shapes draw viewers’ attention to the pigs), the interpretation needs to be logically supported by an observation (the contrast between rectangular and circular shapes). Once you have an argument, consider the significance of these statements. Why does it matter if this painting hints at the tranquility of farm life? Why might the artist have tried to achieve this effect? Briefly discussing why these arguments matter in your thesis can help readers understand the overall significance of your claims. This step may even lead you to delve deeper into recurring themes or topics from class.

Tread lightly

Avoid generalizing about art as a whole, and be cautious about making claims that sound like universal truths. If you find yourself about to say something like “across cultures, blue symbolizes despair,” pause to consider the statement. Would all people, everywhere, from the beginning of human history to the present agree? How do you know? If you find yourself stating that “art has meaning,” consider how you could explain what you see as the specific meaning of the artwork.

Double-check your prompt. Do you need secondary sources to write your paper? Most visual analysis essays in art history will not require secondary sources to write the paper. Rely instead on your close observation of the image or object to inform your analysis and use your knowledge from class to support your argument. Are you being asked to use the same methods to analyze objects as you would for paintings? Be sure to follow the approaches discussed in class.

Some classes may use “description,” “formal analysis” and “visual analysis” as synonyms, but others will not. Typically, a visual analysis essay may ask you to consider how form relates to the social, economic, or political context in which these visual materials were made or exhibited, whereas a formal analysis essay may ask you to make an argument solely about form itself. If your prompt does ask you to consider contextual aspects, and you don’t feel like you can address them based on knowledge from the course, consider reading the section on research papers for further guidance.

2. Comparison essays

Comparison essays often require you to follow the same general process outlined in the preceding sections. The primary difference, of course, is that they ask you to deal with more than one visual source. These assignments usually focus on how the formal elements of two artworks compare and contrast with each other. Resist the urge to turn the essay into a list of similarities and differences.

Comparison essays differ in another important way. Because they typically ask you to connect the visual materials in some way or to explain the significance of the comparison itself, they may require that you comment on the context in which the art was created or displayed.

For example, you might have been asked to write a comparative analysis of the painting discussed in the previous section, George Morland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty (ca. 1800), and an unknown Vicús artist’s Bottle in the Form of a Pig (ca. 200 BCE–600 CE). Both works are illustrated below.

You can begin this kind of essay with the same process of observations and note-taking outlined above for formal analysis essays. Consider using the same questions and categories to get yourself started.

Here are some questions you might ask:

- What techniques were used to create these objects?

- How does the use of color in these two works compare? Is it similar or different?

- What can you say about the composition of the sculpture? How does the artist treat certain formal elements, for example geometry? How do these elements compare to and contrast with those found in the painting?

- How do these works represent their subjects? Are they naturalistic or abstract? How do these artists create these effects? Why do these similarities and differences matter?

As our handout on comparing and contrasting suggests, you can organize these thoughts into a Venn diagram or a chart to help keep the answers to these questions distinct.

For example, some notes on these two artworks have been organized into a chart:

| Pigs and Piglets in a Sty | Both Art Works | Bottle in the Form of a Pig | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Topic | Both depict a pig-like animal | ||

| Number | Focus is on two pigs and two piglets (4 animals total) | Focus is on one pig-like animal that makes up the majority of the vessel; vessel’s spout resembles a bird | |

| Colors | White and pink colors on the animals contrast with browns and blues in background | Both use contrasting colors to focus the viewer’s eye | Borders and other elements are defined by black and cream slip to highlight specific anatomical features |

| Setting | Trees, clouds, and wooden fence in background; animals and trough in foreground | No setting beyond the vessel itself | |

| Shape | Rectilinear, vertical shapes of trees and fence contrast with circular, more horizontal shapes of animals | Both use shape to link individual components to the whole composition | Composed of geometric shapes: the body is formed by a round cylinder; ears are concave pyramids, etc. |

As you determine points of comparison, think about the themes that you have discussed in class. You might consider whether the artworks display similar topics or themes. If both artworks include the same subject matter, for example, how does that similarity contribute to the significance of the comparison? How do these artworks relate to the periods or cultures in which they were produced, and what do those relationships suggest about the comparison? The answers to these questions can typically be informed by your knowledge from class lectures. How have your instructors framed the introduction of individual works in class? What aspects of society or culture have they emphasized to explain why specific formal elements were included or excluded? Once you answer your questions, you might notice that some observations are more important than others.

Writing: developing an interpretation that considers both sources

When drafting your thesis, go beyond simply stating your topic. A statement that says “these representations of pig-like animals have some similarities and differences” doesn’t tell your reader what you will argue in your essay.

To say more, based on the notes in the chart above, you might write the following thesis statement:

Although both artworks depict pig-like animals, they rely on different methods of representing the natural world.

Now you have a place to start. Next, you can say more about your analysis. Ask yourself: “so what?” Why does it matter that these two artworks depict pig-like animals? You might want to return to your class notes at this point. Why did your instructor have you analyze these two works in particular? How does the comparison relate to what you have already discussed in class? Remember, comparison essays will typically ask you to think beyond formal analysis.

While the comparison of a similar subject matter (pig-like animals) may influence your initial argument, you may find that other points of comparison (e.g., the context in which the objects were displayed) allow you to more fully address the matter of significance. Thinking about the comparison in this way, you can write a more complex thesis that answers the “so what?” question. If your class has discussed how artists use animals to comment on their social context, for example, you might explore the symbolic importance of these pig-like animals in nineteenth-century British culture and in first-millenium Vicús culture. What political, social, or religious meanings could these objects have generated? If you find yourself needing to do outside research, look over the final section on research papers below!

Supporting paragraphs

The rest of your comparison essay should address the points raised in your thesis in an organized manner. While you could try several approaches, the two most common organizational tactics are discussing the material “subject-by-subject” and “point-by-point.”

- Subject-by-subject: Organizing the body of the paper in this way involves writing everything that you want to say about Moreland’s painting first (in a series of paragraphs) before moving on to everything about the ceramic bottle (in a series of paragraphs). Using our example, after the introduction, you could include a paragraph that discusses the positioning of the animals in Moreland’s painting, another paragraph that describes the depiction of the pigs’ surroundings, and a third explaining the role of geometry in forming the animals. You would then follow this discussion with paragraphs focused on the same topics, in the same order, for the ancient South American vessel. You could then follow this discussion with a paragraph that synthesizes all of the information and explores the significance of the comparison.

- Point-by-point: This strategy, in contrast, involves discussing a single point of comparison or contrast for both objects at the same time. For example, in a single paragraph, you could examine the use of color in both of our examples. Your next paragraph could move on to the differences in the figures’ setting or background (or lack thereof).

As our use of “pig-like” in this section indicates, titles can be misleading. Many titles are assigned by curators and collectors, in some cases years after the object was produced. While the ceramic vessel is titled Bottle in the Form of a Pig , the date and location suggest it may depict a peccary, a pig-like species indigenous to Peru. As you gather information about your objects, think critically about things like titles and dates. Who assigned the title of the work? If it was someone other than the artist, why might they have given it that title? Don’t always take information like titles and dates at face value.

Be cautious about considering contextual elements not immediately apparent from viewing the objects themselves unless you are explicitly asked to do so (try referring back to the prompt or assignment description; it will often describe the expectation of outside research). You may be able to note that the artworks were created during different periods, in different places, with different functions. Even so, avoid making broad assumptions based on those observations. While commenting on these topics may only require some inference or notes from class, if your argument demands a large amount of outside research, you may be writing a different kind of paper. If so, check out the next section!

3. Research papers

Some assignments in art history ask you to do outside research (i.e., beyond both formal analysis and lecture materials). These writing assignments may ask you to contextualize the visual materials that you are discussing, or they may ask you to explore your material through certain theoretical approaches. More specifically, you may be asked to look at the object’s relationship to ideas about identity, politics, culture, and artistic production during the period in which the work was made or displayed. All of these factors require you to synthesize scholars’ arguments about the materials that you are analyzing. In many cases, you may find little to no research on your specific object. When facing this situation, consider how you can apply scholars’ insights about related materials and the period broadly to your object to form an argument. While we cannot cover all the possibilities here, we’ll highlight a few factors that your instructor may task you with investigating.

Iconography

Papers that ask you to consider iconography may require research on the symbolic role or significance of particular symbols (gestures, objects, etc.). For example, you may need to do some research to understand how pig-like animals are typically represented by the cultural group that made this bottle, the Vicús culture. For the same paper, you would likely research other symbols, notably the bird that forms part of the bottle’s handle, to understand how they relate to one another. This process may involve figuring out how these elements are presented in other artworks and what they mean more broadly.

Artistic style and stylistic period

You may also be asked to compare your object or painting to a particular stylistic category. To determine the typical traits of a style, you may need to hit the library. For example, which period style or stylistic trend does Moreland’s Pigs and Piglets in a Sty belong to? How well does the piece “fit” that particular style? Especially for works that depict the same or similar topics, how might their different styles affect your interpretation? Assignments that ask you to consider style as a factor may require that you do some research on larger historical or cultural trends that influenced the development of a particular style.

Provenance research asks you to find out about the “life” of the object itself. This research can include the circumstances surrounding the work’s production and its later ownership. For the two works discussed in this handout, you might research where these objects were originally displayed and how they ended up in the museum collections in which they now reside. What kind of argument could you develop with this information? For example, you might begin by considering that many bottles and jars resembling the Bottle in the Form of a Pig can be found in various collections of Pre-Columbian art around the world. Where do these objects originate? Do they come from the same community or region?

Patronage study

Prompts that ask you to discuss patronage might ask you to think about how, when, where, and why the patron (the person who commissions or buys the artwork or who supports the artist) acquired the object from the artist. The assignment may ask you to comment on the artist-patron relationship, how the work fit into a broader series of commissions, and why patrons chose particular artists or even particular subjects.

Additional resources

To look up recent articles, ask your librarian about the Art Index, RILA, BHA, and Avery Index. Check out www.lib.unc.edu/art/index.html for further information!

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Adams, Laurie Schneider. 2003. Looking at Art . Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Barnet, Sylvan. 2015. A Short Guide to Writing about Art , 11th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Tate Galleries. n.d. “Art Terms.” Accessed November 1, 2020. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms .

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Art Degrees

- Galleries & Exhibits

- Request More Info

Art History Resources

- Guidelines for Analysis of Art

- Formal Analysis Paper Examples

Guidelines for Writing Art History Research Papers

- Oral Report Guidelines

- Annual Arkansas College Art History Symposium

Writing a paper for an art history course is similar to the analytical, research-based papers that you may have written in English literature courses or history courses. Although art historical research and writing does include the analysis of written documents, there are distinctive differences between art history writing and other disciplines because the primary documents are works of art. A key reference guide for researching and analyzing works of art and for writing art history papers is the 10th edition (or later) of Sylvan Barnet’s work, A Short Guide to Writing about Art . Barnet directs students through the steps of thinking about a research topic, collecting information, and then writing and documenting a paper.

A website with helpful tips for writing art history papers is posted by the University of North Carolina.

Wesleyan University Writing Center has a useful guide for finding online writing resources.

The following are basic guidelines that you must use when documenting research papers for any art history class at UA Little Rock. Solid, thoughtful research and correct documentation of the sources used in this research (i.e., footnotes/endnotes, bibliography, and illustrations**) are essential. Additionally, these guidelines remind students about plagiarism, a serious academic offense.

Paper Format

Research papers should be in a 12-point font, double-spaced. Ample margins should be left for the instructor’s comments. All margins should be one inch to allow for comments. Number all pages. The cover sheet for the paper should include the following information: title of paper, your name, course title and number, course instructor, and date paper is submitted. A simple presentation of a paper is sufficient. Staple the pages together at the upper left or put them in a simple three-ring folder or binder. Do not put individual pages in plastic sleeves.

Documentation of Resources

The Chicago Manual of Style (CMS), as described in the most recent edition of Sylvan Barnet’s A Short Guide to Writing about Art is the department standard. Although you may have used MLA style for English papers or other disciplines, the Chicago Style is required for all students taking art history courses at UA Little Rock. There are significant differences between MLA style and Chicago Style. A “Quick Guide” for the Chicago Manual of Style footnote and bibliography format is found http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org/tools_citationguide.html. The footnote examples are numbered and the bibliography example is last. Please note that the place of publication and the publisher are enclosed in parentheses in the footnote, but they are not in parentheses in the bibliography. Examples of CMS for some types of note and bibliography references are given below in this Guideline. Arabic numbers are used for footnotes. Some word processing programs may have Roman numerals as a choice, but the standard is Arabic numbers. The use of super script numbers, as given in examples below, is the standard in UA Little Rock art history papers.

The chapter “Manuscript Form” in the Barnet book (10th edition or later) provides models for the correct forms for footnotes/endnotes and the bibliography. For example, the note form for the FIRST REFERENCE to a book with a single author is:

1 Bruce Cole, Italian Art 1250-1550 (New York: New York University Press, 1971), 134.

But the BIBLIOGRAPHIC FORM for that same book is:

Cole, Bruce. Italian Art 1250-1550. New York: New York University Press. 1971.

The FIRST REFERENCE to a journal article (in a periodical that is paginated by volume) with a single author in a footnote is:

2 Anne H. Van Buren, “Madame Cézanne’s Fashions and the Dates of Her Portraits,” Art Quarterly 29 (1966): 199.

The FIRST REFERENCE to a journal article (in a periodical that is paginated by volume) with a single author in the BIBLIOGRAPHY is:

Van Buren, Anne H. “Madame Cézanne’s Fashions and the Dates of Her Portraits.” Art Quarterly 29 (1966): 185-204.

If you reference an article that you found through an electronic database such as JSTOR, you do not include the url for JSTOR or the date accessed in either the footnote or the bibliography. This is because the article is one that was originally printed in a hard-copy journal; what you located through JSTOR is simply a copy of printed pages. Your citation follows the same format for an article in a bound volume that you may have pulled from the library shelves. If, however, you use an article that originally was in an electronic format and is available only on-line, then follow the “non-print” forms listed below.

B. Non-Print

Citations for Internet sources such as online journals or scholarly web sites should follow the form described in Barnet’s chapter, “Writing a Research Paper.” For example, the footnote or endnote reference given by Barnet for a web site is:

3 Nigel Strudwick, Egyptology Resources , with the assistance of The Isaac Newton Institute for Mathematical Sciences, Cambridge University, 1994, revised 16 June 2008, http://www.newton.ac.uk/egypt/ , 24 July 2008.

If you use microform or microfilm resources, consult the most recent edition of Kate Turabian, A Manual of Term Paper, Theses and Dissertations. A copy of Turabian is available at the reference desk in the main library.

C. Visual Documentation (Illustrations)

Art history papers require visual documentation such as photographs, photocopies, or scanned images of the art works you discuss. In the chapter “Manuscript Form” in A Short Guide to Writing about Art, Barnet explains how to identify illustrations or “figures” in the text of your paper and how to caption the visual material. Each photograph, photocopy, or scanned image should appear on a single sheet of paper unless two images and their captions will fit on a single sheet of paper with one inch margins on all sides. Note also that the title of a work of art is always italicized. Within the text, the reference to the illustration is enclosed in parentheses and placed at the end of the sentence. A period for the sentence comes after the parenthetical reference to the illustration. For UA Little Rcok art history papers, illustrations are placed at the end of the paper, not within the text. Illustration are not supplied as a Powerpoint presentation or as separate .jpgs submitted in an electronic format.

Edvard Munch’s painting The Scream, dated 1893, represents a highly personal, expressive response to an experience the artist had while walking one evening (Figure 1).

The caption that accompanies the illustration at the end of the paper would read:

Figure 1. Edvard Munch, The Scream, 1893. Tempera and casein on cardboard, 36 x 29″ (91.3 x 73.7 cm). Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo, Norway.

Plagiarism is a form of thievery and is illegal. According to Webster’s New World Dictionary, to plagiarize is to “take and pass off as one’s own the ideas, writings, etc. of another.” Barnet has some useful guidelines for acknowledging sources in his chapter “Manuscript Form;” review them so that you will not be mguilty of theft. Another useful website regarding plagiarism is provided by Cornell University, http://plagiarism.arts.cornell.edu/tutorial/index.cfm

Plagiarism is a serious offense, and students should understand that checking papers for plagiarized content is easy to do with Internet resources. Plagiarism will be reported as academic dishonesty to the Dean of Students; see Section VI of the Student Handbook which cites plagiarism as a specific violation. Take care that you fully and accurately acknowledge the source of another author, whether you are quoting the material verbatim or paraphrasing. Borrowing the idea of another author by merely changing some or even all of your source’s words does not allow you to claim the ideas as your own. You must credit both direct quotes and your paraphrases. Again, Barnet’s chapter “Manuscript Form” sets out clear guidelines for avoiding plagiarism.

VISIT OUR GALLERIES SEE UPCOMING EXHIBITS

- School of Art and Design

- Windgate Center of Art + Design, Room 202 2801 S University Avenue Little Rock , AR 72204

- Phone: 501-916-3182 Fax: 501-683-7022 (fax)

- More contact information

Connect With Us

UA Little Rock is an accredited member of the National Association of Schools of Art and Design.

Additional Navigation and Search

- Search Icon

Accessibility Options

Art history writing guide.

I. Introduction II. Writing Assignments III. Discipline-Specific Strategies IV. Keep in Mind V. Appendix

Introduction

At the heart of every art history paper is a close visual analysis of at least one work of art. In art history you are building an argument about something visual. Depending on the assignment, this analysis may be the basis for an assignment or incorporated into a paper as support to contextualize an argument. To guide students in how to write an art history paper, the Art History Department suggests that you begin with a visual observation that leads to the development of an interpretive thesis/argument. The writing uses visual observations as evidence to support an argument about the art that is being analyzed.

Writing Assignments

You will be expected to write several different kinds of art history papers. They include:

- Close Visual Analysis Essays

- Close Visual Analysis in dialogue with scholarly essays

- Research Papers

Close Visual Analysis pieces are the most commonly written papers in an introductory art history course. You will have to look at a work of art and analyze it in its entirety. The analysis and discussion should provide a clearly articulated interpretation of the object. Your argument for this paper should be backed up with careful description and analysis of the visual evidence that led you to your conclusion.

Close Visual Analysis in dialogue with scholarly essays combines formal analysis with close textual analysis.

Research papers range from theoretic studies to critical histories. Based on library research, students are asked to synthesize analyses of the scholarship in relation to the work upon which it is based.

Discipline-Specific Strategies

As with all writing assignment, a close visual analysis is a process. The work you do before you actually start writing can be just as important as what you consider when writing up your analysis.

Conducting the analysis :

- Ask questions as you are studying the artwork. Consider, for example, how does each element of the artwork contribute to the work's overall meaning. How do you know? How do elements relate to each other? What effect is produced by their juxtaposition

- Use the criteria provided by your professor to complete your analysis. This criteria may include forms, space, composition, line, color, light, texture, physical characteristics, and expressive content.

Writing the analysis:

- Develop a strong interpretive thesis about what you think is the overall effect or meaning of the image.

- Ground your argument in direct and specific references to the work of art itself.

- Describe the image in specific terms and with the criteria that you used for the analysis. For example, a stray diagonal from the upper left corner leads the eye to...

- Create an introduction that sets the stage for your paper by briefly describing the image you are analyzing and by stating your thesis.

- Explain how the elements work together to create an overall effect. Try not to just list the elements, but rather explain how they lead to or support your analysis.

- Contextualize the image within a historical and cultural framework only when required for an assignment. Some assignments actually prefer that you do not do this. Remember not to rely on secondary sources for formal analysis. The goal is to see what in the image led to your analysis; therefore, you will not need secondary sources in this analysis. Be certain to show how each detail supports your argument.

- Include only the elements needed to explain and support your analysis. You do not need to include everything you saw since this excess information may detract from your main argument.

Keep in Mind

- An art history paper has an argument that needs to be supported with elements from the image being analyzed.

- Avoid making grand claims. For example, saying "The artist wanted..." is different from "The warm palette evokes..." The first phrasing necessitates proof of the artist's intent, as opposed to the effect of the image.

- Make sure that your paper isn't just description. You should choose details that illustrate your central ideas and further the purpose of your paper.

If you find you are still having trouble writing your art history paper, please speak to your professor, and feel free to make an appointment at the Writing Center. For further reading, see Sylvan Barnet's A Short Guide to Writing about Art , 5th edition.

Additional Site Navigation

Social media links, additional navigation links.

- Alumni Resources & Events

- Athletics & Wellness

- Campus Calendar

- Parent & Family Resources

Helpful Information

Dining hall hours, next trains to philadelphia, next trico shuttles.

Swarthmore Traditions

How to Plan Your Classes

The Swarthmore Bucket List

Search the website

How to Write a Thesis Statement (Full Guide + 60 Examples)

Crafting the perfect thesis statement is an art form that sets the foundation for your entire paper.

Here is how to write a thesis statement:

Write a thesis statement by clearly stating your topic, expressing your position, and providing key points. For example: “Social media impacts teens by influencing self-esteem, enabling cyberbullying, and shaping social interactions.” Be specific, concise, and arguable.

This ultimate guide will break down everything you need to know about how to write a thesis statement, plus 60 examples.

What Is a Thesis Statement?

Table of Contents

A thesis statement is a concise summary of the main point or claim of an essay, research paper, or other piece of academic writing.

It presents the topic of your paper and your position on the topic, ideally in a single sentence.

Think of it as the roadmap to your paper—it guides your readers through your arguments and provides a clear direction.

Key Elements of a Thesis Statement

- Clarity: Your thesis should be clear and specific.

- Position: It should convey your stance on the topic.

- Argument: The statement should make a claim that others might dispute.

Types of Thesis Statements

There are various types of thesis statements depending on the kind of paper you’re writing.

Here are the main ones:

- Standard Method – This is the classic thesis statement used in many academic essays. It provides a straightforward approach, clearly stating the main argument or claim and outlining the supporting points.

- Research Paper – Designed for research papers, this type involves extensive research and evidence. It presents a hypothesis or a central argument based on your research findings.

- Informative Essay – Used for essays that aim to inform or explain a topic. It provides a clear summary of what the reader will learn.

- Persuasive Essay – For essays meant to persuade or convince the reader of a particular point of view. It clearly states your position and outlines your main arguments.

- Compare and Contrast Essay – Used when comparing two or more subjects. It highlights the similarities and differences between the subjects and presents a clear argument based on these comparisons.

- Analytical Essay – Breaks down an issue or idea into its component parts, evaluates the issue or idea, and presents this breakdown and evaluation to the audience.

- Argumentative Essay – Makes a claim about a topic and justifies this claim with specific evidence. It’s similar to the persuasive essay but usually requires more evidence and a more formal tone.

- Expository Essay – Explains or describes a topic in a straightforward, logical manner. It provides a balanced analysis of a subject based on facts without opinions.

- Narrative Essay – Tells a story or relates an event. The thesis statement for a narrative essay usually highlights the main point or lesson of the story.

- Cause and Effect Essay – Explores the causes of a particular event or situation and its effects. It provides a clear argument about the cause and effect relationship.

How to Write a Thesis Statement (Standard Method)

Writing a standard thesis statement involves a few straightforward steps.

Here’s a detailed guide:

- Identify Your Topic: What is your essay about?

- Take a Stance: What is your position on the topic?

- Outline Your Main Points: What are the key arguments that support your stance?

- Combine All Elements: Formulate a single, coherent sentence that encompasses all the above points.

- “Social media has a significant impact on teenagers because it influences their self-esteem, provides a platform for cyberbullying, and shapes their social interactions.”

- “Climate change is a pressing issue that requires immediate action because it threatens global ecosystems, endangers human health, and disrupts economies.”

- “The rise of remote work is transforming the modern workplace by increasing flexibility, reducing overhead costs, and enhancing work-life balance.”

- “School uniforms should be mandatory in public schools as they promote equality, reduce bullying, and simplify the morning routine.”

- “Digital literacy is essential in today’s world because it improves communication, enhances job prospects, and enables informed decision-making.”

How to Write a Thesis Statement for a Research Paper

Research papers require a more detailed and evidence-based thesis.

Here’s how to craft one:

- Start with a Research Question: What are you trying to find out?

- Conduct Preliminary Research: Gather evidence and sources.

- Formulate a Hypothesis: Based on your research, what do you think will happen?

- Refine Your Thesis: Make it specific and arguable.

- “The implementation of renewable energy sources can significantly reduce carbon emissions in urban areas, as evidenced by case studies in cities like Copenhagen and Vancouver.”

- “Genetically modified crops have the potential to improve food security, but their impact on biodiversity and human health requires further investigation.”

- “The use of artificial intelligence in healthcare can improve diagnostic accuracy and patient outcomes, but ethical concerns about data privacy and algorithmic bias must be addressed.”

- “Urban green spaces contribute to mental well-being and community cohesion, as demonstrated by longitudinal studies in various metropolitan areas.”

- “Microplastic pollution in oceans poses a severe threat to marine life and human health, highlighting the need for stricter waste management policies.”

How to Write a Thesis Statement for an Essay

You’ll write thesis statements a little differently for different kinds of essays.

Informative Essay

- Choose Your Topic: What are you informing your readers about?

- Outline Key Points: What are the main pieces of information?

- Draft Your Statement: Clearly state the purpose and main points.

- “The process of photosynthesis is essential for plant life as it converts light energy into chemical energy, produces oxygen, and is the basis for the food chain.”

- “The human digestive system is a complex series of organs and glands that process food, absorb nutrients, and eliminate waste.”

- “The Industrial Revolution was a period of major technological advancement and social change that reshaped the economies and societies of Europe and North America.”

- “The history of the internet from its early development in the 1960s to its current role in global communication and commerce is a fascinating journey of innovation and transformation.”

- “The impact of climate change on Arctic ecosystems is profound, affecting wildlife, indigenous communities, and global weather patterns.”

Persuasive Essay

- Identify Your Position: What are you trying to convince your reader of?

- Gather Supporting Evidence: What evidence backs up your position?

- Combine Elements: Make a clear, arguable statement.

- “Implementing a four-day workweek can improve productivity and employee well-being, as supported by studies from Iceland and Japan.”

- “The death penalty should be abolished as it is inhumane, does not deter crime, and risks executing innocent people.”

- “Public transportation should be made free to reduce traffic congestion, decrease pollution, and promote social equity.”

- “Recycling should be mandatory to conserve natural resources, reduce landfill waste, and protect the environment.”

- “Vaccination should be mandatory to protect public health and prevent the spread of contagious diseases.”

Compare and Contrast Essay

- Choose Subjects to Compare: What are the two (or more) subjects?

- Determine the Basis of Comparison: What specific aspects are you comparing?

- Draft the Thesis: Clearly state the subjects and the comparison.

- “While both solar and wind energy are renewable sources, solar energy is more versatile and can be used in a wider variety of environments.”

- “Although both capitalism and socialism aim to improve economic welfare, capitalism emphasizes individual freedom while socialism focuses on collective equality.”

- “Traditional classroom education and online learning each offer unique benefits, but online learning provides greater flexibility and access to resources.”

- “The novels ‘1984’ by George Orwell and ‘Brave New World’ by Aldous Huxley both depict dystopian societies, but ‘1984’ focuses on totalitarianism while ‘Brave New World’ explores the dangers of technological control.”

- “While iOS and Android operating systems offer similar functionality, iOS provides a more streamlined user experience, whereas Android offers greater customization options.”

How to Write a Thesis Statement for an Analytical Essay

An analytical essay breaks down an issue or idea into its component parts, evaluates the issue or idea, and presents this breakdown and evaluation to the audience.

- Choose Your Topic: What will you analyze?

- Identify Key Components: What are the main parts of your analysis?

- Formulate Your Thesis: Combine the components into a coherent statement.

- “Shakespeare’s ‘Hamlet’ explores themes of madness and revenge through the complex characterization of Hamlet and his interactions with other characters.”

- “The economic policies of the New Deal addressed the Great Depression by implementing financial reforms, creating job opportunities, and providing social welfare programs.”

- “The symbolism in ‘The Great Gatsby’ by F. Scott Fitzgerald reflects the moral decay and social stratification of the Jazz Age.”

- “The narrative structure of ‘Inception’ uses nonlinear storytelling to explore the complexities of dreams and reality.”

- “The use of color in Wes Anderson’s films enhances the whimsical and nostalgic tone of his storytelling.”

How to Write a Thesis Statement for an Argumentative Essay

An argumentative essay makes a claim about a topic and justifies this claim with specific evidence.

It’s similar to the persuasive essay but usually requires more evidence and a more formal tone.

- Choose Your Topic: What are you arguing about?

- Gather Evidence: What evidence supports your claim?

- Formulate Your Thesis: Make a clear, evidence-based statement.

- “Climate change is primarily driven by human activities, such as deforestation and the burning of fossil fuels, which increase greenhouse gas emissions.”

- “The benefits of universal healthcare outweigh the costs, as it ensures equal access to medical services, reduces overall healthcare expenses, and improves public health.”

- “The death penalty should be abolished because it violates human rights, is not a deterrent to crime, and risks the execution of innocent people.”

- “Animal testing for cosmetics should be banned as it is unethical, unnecessary, and alternatives are available.”

- “Net neutrality should be maintained to ensure a free and open internet, preventing service providers from prioritizing or blocking content.”

How to Write a Thesis Statement for an Expository Essay

An expository essay explains or describes a topic in a straightforward, logical manner.

It provides a balanced analysis of a subject based on facts without opinions.

- Choose Your Topic: What are you explaining or describing?

- Outline Key Points: What are the main facts or components?

- Formulate Your Thesis: Combine the elements into a clear statement.

- “The water cycle consists of evaporation, condensation, and precipitation, which are essential for maintaining the earth’s water balance.”

- “The human respiratory system is responsible for taking in oxygen and expelling carbon dioxide through a series of organs, including the lungs, trachea, and diaphragm.”

- “Photosynthesis in plants involves the absorption of light energy by chlorophyll, which converts carbon dioxide and water into glucose and oxygen.”

- “The structure of DNA is a double helix composed of nucleotides, which are the building blocks of genetic information.”

- “The process of mitosis ensures that cells divide correctly, allowing for growth, repair, and reproduction in living organisms.”

How to Write a Thesis Statement for a Narrative Essay

A narrative essay tells a story or relates an event.

The thesis statement for a narrative essay usually highlights the main point or lesson of the story.

- Identify the Main Point: What is the main lesson or theme of your story?

- Outline Key Events: What are the key events that support this point?

- Formulate Your Thesis: Combine the main point and events into a coherent statement.

- “Overcoming my fear of public speaking in high school taught me the value of confidence and perseverance.”

- “My summer volunteering at a wildlife rescue center showed me the importance of compassion and teamwork.”

- “A family road trip across the country provided me with unforgettable memories and a deeper appreciation for our diverse landscapes.”

- “Moving to a new city for college challenged me to adapt to new environments and build independence.”

- “A childhood friendship that ended in betrayal taught me the importance of trust and resilience.”

How to Write a Thesis Statement for a Cause and Effect Essay

A cause and effect essay explores the causes of a particular event or situation and its effects.

It provides a clear argument about the cause and effect relationship.

- Identify the Event or Situation: What are you analyzing?

- Determine the Causes: What are the reasons behind this event or situation?

- Identify the Effects: What are the consequences?

- Formulate Your Thesis: Combine the causes and effects into a coherent statement.

- “The rise in global temperatures is primarily caused by human activities, such as burning fossil fuels, and leads to severe weather patterns and rising sea levels.”

- “The introduction of invasive species in an ecosystem disrupts the balance and leads to the decline of native species.”

- “Economic recession is caused by a combination of factors, including high unemployment rates and declining consumer confidence, and results in reduced business investments and government spending.”

- “Prolonged exposure to screen time can cause digital eye strain and sleep disturbances, affecting overall health and productivity.”

- “Deforestation contributes to soil erosion and loss of biodiversity, leading to the degradation of ecosystems and reduced agricultural productivity.”

How to Write a Good Thesis Statement

Writing a good thesis statement is all about clarity and specificity.

Here’s a formula to help you:

- State the Topic: What are you writing about?

- Express Your Opinion: What do you think about the topic?

- Provide a Reason: Why do you think this way?

- “Remote work is beneficial because it offers flexibility, reduces commuting time, and increases job satisfaction.”

- “Regular exercise is essential for maintaining physical and mental health as it boosts energy levels, improves mood, and reduces the risk of chronic diseases.”

- “Reading fiction enhances empathy by allowing readers to experience different perspectives and emotions.”

- “A plant-based diet is advantageous for both personal health and environmental sustainability.”

- “Learning a second language enhances cognitive abilities and opens up cultural and professional opportunities.”

Check out this video about how to write a strong thesis statement:

How to Write a Thesis Statement (Formula + Template)

Use this simple formula to craft your thesis statement:

[Main Topic] + [Your Opinion/Position] + [Reason/Key Points]

Template: “__________ (main topic) has __________ (your opinion) because __________ (reason/key points).”

- “Electric cars are the future of transportation because they reduce greenhouse gas emissions, lower fuel costs, and require less maintenance.”

- “Social media platforms should implement stricter privacy controls because user data is vulnerable to breaches, exploitation, and misuse.”

- “Higher education should be more affordable to ensure equal access and promote social mobility.”

- “Television news often fails to provide balanced coverage, leading to public misinformation.”

- “Volunteer work should be encouraged in schools to foster community engagement and personal development.”

Thesis Statement Tips

Writing a strong thesis statement is crucial for a successful essay. Here are some tips to help you craft a killer thesis statement:

- Be Specific: Avoid vague language. Make sure your thesis statement clearly defines your argument or main point.

- Be Concise: Keep it to one or two sentences. Your thesis statement should be brief and to the point.

- Make It Arguable: Ensure that your thesis statement presents a claim or argument that can be disputed.

- Place It Appropriately: Typically, your thesis statement should be placed at the end of your introduction paragraph.

- Revise and Refine: Don’t be afraid to revise your thesis statement as you write and refine your essay. It should evolve as your ideas develop.

Common Thesis Statement Errors

Avoid these common errors when crafting your thesis statement:

- Too Broad: A thesis statement that is too broad makes it difficult to focus your essay. Narrow it down to a specific point.

- Too Vague: Avoid vague language that lacks specificity. Be clear about what you’re arguing.

- Lacks an Argument: Ensure that your thesis statement makes a clear argument or claim. Avoid statements that are purely factual or descriptive.

- Too Complex: A thesis statement should be straightforward and easy to understand. Avoid overly complex sentences.

- Off-Topic: Make sure your thesis statement is directly related to the topic of your essay. Stay on track.

How Do You Start a Thesis Statement?

Starting a thesis statement involves using clear and concise language that sets the stage for your argument.

Here are some exact words and phrases to begin with:

- “The purpose of this paper is to…”

- “This essay will argue that…”

- “In this essay, I will demonstrate that…”

- “The central idea of this paper is…”

- “This research aims to prove that…”

- “This study focuses on…”

- “This analysis will show that…”

- “The main argument presented in this paper is…”

- “The goal of this essay is to…”

- “Through this research, it will be shown that…”

How Long Should a Thesis Statement Be?

A thesis statement should be clear and concise, typically one to two sentences long.

Aim for 20 to 30 words, ensuring it includes the main topic, your position, and the key points that will be covered in your paper.

This provides a focused and precise summary of your argument, making it easier for readers to understand the main direction of your essay or research paper.

While brevity is essential, it’s also crucial to provide enough detail to convey the scope of your argument.

Avoid overly complex sentences that can confuse readers. Instead, strive for a balance between clarity and comprehensiveness, ensuring your thesis statement is straightforward and informative.

Summary Table of Thesis Statement Writing

| Type of Thesis Statement | Example |

|---|---|

| Standard Method | “Social media influences teenagers’ self-esteem and social interactions.” |

| Research Paper | “Renewable energy reduces urban carbon emissions, shown by case studies.” |

| Informative Essay | “Photosynthesis converts light energy into chemical energy for plants.” |

| Persuasive Essay | “A four-day workweek improves productivity and well-being.” |

| Compare and Contrast Essay | “Solar energy is more versatile than wind energy.” |

| Analytical Essay | “The symbolism in ‘The Great Gatsby’ reflects social stratification.” |

| Argumentative Essay | “Climate change is driven by human activities, requiring urgent action.” |

| Expository Essay | “The water cycle is essential for maintaining earth’s water balance.” |

| Narrative Essay | “Overcoming my fear of public speaking taught me confidence.” |

| Cause and Effect Essay | “Deforestation leads to soil erosion and loss of biodiversity.” |

Final Thoughts: How to Write a Thesis Statement

Writing a strong thesis statement is the cornerstone of a successful paper.

It guides your writing and helps your readers understand your argument. Remember to be clear, specific, and concise. With practice, you’ll master the art of crafting killer thesis statements.

Read This Next:

- How to Write a Hypothesis [31 Tips + Examples]

- How to Write a Topic Sentence (30+ Tips & Examples)

- How to Write a Paragraph [Ultimate Guide + Examples] What Is A Universal Statement In Writing? (Explained) 21 Best Ways To Write Essays When You Are Stuck [Examples]

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Tips for Writing Your Thesis Statement

1. Determine what kind of paper you are writing:

- An analytical paper breaks down an issue or an idea into its component parts, evaluates the issue or idea, and presents this breakdown and evaluation to the audience.

- An expository (explanatory) paper explains something to the audience.

- An argumentative paper makes a claim about a topic and justifies this claim with specific evidence. The claim could be an opinion, a policy proposal, an evaluation, a cause-and-effect statement, or an interpretation. The goal of the argumentative paper is to convince the audience that the claim is true based on the evidence provided.

If you are writing a text that does not fall under these three categories (e.g., a narrative), a thesis statement somewhere in the first paragraph could still be helpful to your reader.

2. Your thesis statement should be specific—it should cover only what you will discuss in your paper and should be supported with specific evidence.

3. The thesis statement usually appears at the end of the first paragraph of a paper.

4. Your topic may change as you write, so you may need to revise your thesis statement to reflect exactly what you have discussed in the paper.

Thesis Statement Examples

Example of an analytical thesis statement:

The paper that follows should:

- Explain the analysis of the college admission process

- Explain the challenge facing admissions counselors

Example of an expository (explanatory) thesis statement:

- Explain how students spend their time studying, attending class, and socializing with peers

Example of an argumentative thesis statement:

- Present an argument and give evidence to support the claim that students should pursue community projects before entering college

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What Is a Thesis? | Ultimate Guide & Examples

What Is a Thesis? | Ultimate Guide & Examples

Published on September 14, 2022 by Tegan George . Revised on April 16, 2024.

A thesis is a type of research paper based on your original research. It is usually submitted as the final step of a master’s program or a capstone to a bachelor’s degree.

Writing a thesis can be a daunting experience. Other than a dissertation , it is one of the longest pieces of writing students typically complete. It relies on your ability to conduct research from start to finish: choosing a relevant topic , crafting a proposal , designing your research , collecting data , developing a robust analysis, drawing strong conclusions , and writing concisely .

Thesis template

You can also download our full thesis template in the format of your choice below. Our template includes a ready-made table of contents , as well as guidance for what each chapter should include. It’s easy to make it your own, and can help you get started.

Download Word template Download Google Docs template

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Thesis vs. thesis statement, how to structure a thesis, acknowledgements or preface, list of figures and tables, list of abbreviations, introduction, literature review, methodology, reference list, proofreading and editing, defending your thesis, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about theses.

You may have heard the word thesis as a standalone term or as a component of academic writing called a thesis statement . Keep in mind that these are two very different things.

- A thesis statement is a very common component of an essay, particularly in the humanities. It usually comprises 1 or 2 sentences in the introduction of your essay , and should clearly and concisely summarize the central points of your academic essay .

- A thesis is a long-form piece of academic writing, often taking more than a full semester to complete. It is generally a degree requirement for Master’s programs, and is also sometimes required to complete a bachelor’s degree in liberal arts colleges.

- In the US, a dissertation is generally written as a final step toward obtaining a PhD.

- In other countries (particularly the UK), a dissertation is generally written at the bachelor’s or master’s level.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

The final structure of your thesis depends on a variety of components, such as:

- Your discipline

- Your theoretical approach

Humanities theses are often structured more like a longer-form essay . Just like in an essay, you build an argument to support a central thesis.

In both hard and social sciences, theses typically include an introduction , literature review , methodology section , results section , discussion section , and conclusion section . These are each presented in their own dedicated section or chapter. In some cases, you might want to add an appendix .

Thesis examples

We’ve compiled a short list of thesis examples to help you get started.

- Example thesis #1: “Abolition, Africans, and Abstraction: the Influence of the ‘Noble Savage’ on British and French Antislavery Thought, 1787-1807” by Suchait Kahlon.

- Example thesis #2: “’A Starving Man Helping Another Starving Man’: UNRRA, India, and the Genesis of Global Relief, 1943-1947″ by Julian Saint Reiman.

The very first page of your thesis contains all necessary identifying information, including:

- Your full title

- Your full name

- Your department

- Your institution and degree program

- Your submission date.

Sometimes the title page also includes your student ID, the name of your supervisor, or the university’s logo. Check out your university’s guidelines if you’re not sure.

Read more about title pages

The acknowledgements section is usually optional. Its main point is to allow you to thank everyone who helped you in your thesis journey, such as supervisors, friends, or family. You can also choose to write a preface , but it’s typically one or the other, not both.

Read more about acknowledgements Read more about prefaces

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

An abstract is a short summary of your thesis. Usually a maximum of 300 words long, it’s should include brief descriptions of your research objectives , methods, results, and conclusions. Though it may seem short, it introduces your work to your audience, serving as a first impression of your thesis.

Read more about abstracts

A table of contents lists all of your sections, plus their corresponding page numbers and subheadings if you have them. This helps your reader seamlessly navigate your document.

Your table of contents should include all the major parts of your thesis. In particular, don’t forget the the appendices. If you used heading styles, it’s easy to generate an automatic table Microsoft Word.

Read more about tables of contents

While not mandatory, if you used a lot of tables and/or figures, it’s nice to include a list of them to help guide your reader. It’s also easy to generate one of these in Word: just use the “Insert Caption” feature.

Read more about lists of figures and tables

If you have used a lot of industry- or field-specific abbreviations in your thesis, you should include them in an alphabetized list of abbreviations . This way, your readers can easily look up any meanings they aren’t familiar with.

Read more about lists of abbreviations

Relatedly, if you find yourself using a lot of very specialized or field-specific terms that may not be familiar to your reader, consider including a glossary . Alphabetize the terms you want to include with a brief definition.

Read more about glossaries

An introduction sets up the topic, purpose, and relevance of your thesis, as well as expectations for your reader. This should:

- Ground your research topic , sharing any background information your reader may need

- Define the scope of your work

- Introduce any existing research on your topic, situating your work within a broader problem or debate

- State your research question(s)

- Outline (briefly) how the remainder of your work will proceed

In other words, your introduction should clearly and concisely show your reader the “what, why, and how” of your research.

Read more about introductions

A literature review helps you gain a robust understanding of any extant academic work on your topic, encompassing:

- Selecting relevant sources

- Determining the credibility of your sources

- Critically evaluating each of your sources

- Drawing connections between sources, including any themes, patterns, conflicts, or gaps

A literature review is not merely a summary of existing work. Rather, your literature review should ultimately lead to a clear justification for your own research, perhaps via:

- Addressing a gap in the literature

- Building on existing knowledge to draw new conclusions

- Exploring a new theoretical or methodological approach

- Introducing a new solution to an unresolved problem

- Definitively advocating for one side of a theoretical debate

Read more about literature reviews

Theoretical framework

Your literature review can often form the basis for your theoretical framework, but these are not the same thing. A theoretical framework defines and analyzes the concepts and theories that your research hinges on.

Read more about theoretical frameworks

Your methodology chapter shows your reader how you conducted your research. It should be written clearly and methodically, easily allowing your reader to critically assess the credibility of your argument. Furthermore, your methods section should convince your reader that your method was the best way to answer your research question.

A methodology section should generally include:

- Your overall approach ( quantitative vs. qualitative )

- Your research methods (e.g., a longitudinal study )

- Your data collection methods (e.g., interviews or a controlled experiment

- Any tools or materials you used (e.g., computer software)

- The data analysis methods you chose (e.g., statistical analysis , discourse analysis )

- A strong, but not defensive justification of your methods

Read more about methodology sections

Your results section should highlight what your methodology discovered. These two sections work in tandem, but shouldn’t repeat each other. While your results section can include hypotheses or themes, don’t include any speculation or new arguments here.

Your results section should:

- State each (relevant) result with any (relevant) descriptive statistics (e.g., mean , standard deviation ) and inferential statistics (e.g., test statistics , p values )

- Explain how each result relates to the research question

- Determine whether the hypothesis was supported

Additional data (like raw numbers or interview transcripts ) can be included as an appendix . You can include tables and figures, but only if they help the reader better understand your results.

Read more about results sections

Your discussion section is where you can interpret your results in detail. Did they meet your expectations? How well do they fit within the framework that you built? You can refer back to any relevant source material to situate your results within your field, but leave most of that analysis in your literature review.

For any unexpected results, offer explanations or alternative interpretations of your data.

Read more about discussion sections

Your thesis conclusion should concisely answer your main research question. It should leave your reader with an ultra-clear understanding of your central argument, and emphasize what your research specifically has contributed to your field.

Why does your research matter? What recommendations for future research do you have? Lastly, wrap up your work with any concluding remarks.

Read more about conclusions

In order to avoid plagiarism , don’t forget to include a full reference list at the end of your thesis, citing the sources that you used. Choose one citation style and follow it consistently throughout your thesis, taking note of the formatting requirements of each style.

Which style you choose is often set by your department or your field, but common styles include MLA , Chicago , and APA.

Create APA citations Create MLA citations