Reference management. Clean and simple.

The top list of academic research databases

2. Web of Science

5. ieee xplore, 6. sciencedirect, 7. directory of open access journals (doaj), get the most out of your academic research database, frequently asked questions about academic research databases, related articles.

Whether you are writing a thesis , dissertation, or research paper it is a key task to survey prior literature and research findings. More likely than not, you will be looking for trusted resources, most likely peer-reviewed research articles.

Academic research databases make it easy to locate the literature you are looking for. We have compiled the top list of trusted academic resources to help you get started with your research:

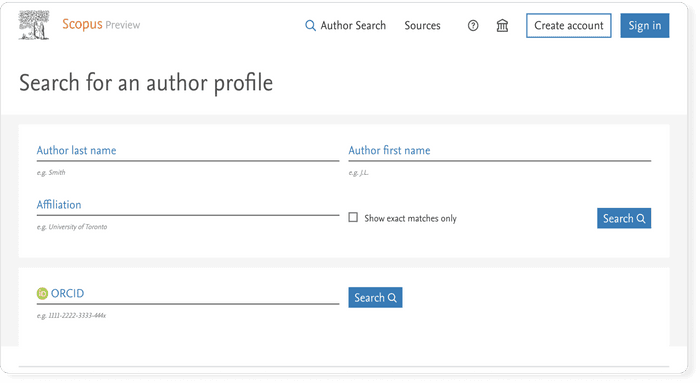

Scopus is one of the two big commercial, bibliographic databases that cover scholarly literature from almost any discipline. Besides searching for research articles, Scopus also provides academic journal rankings, author profiles, and an h-index calculator .

- Coverage: 90.6 million core records

- References: N/A

- Discipline: Multidisciplinary

- Access options: Limited free preview, full access by institutional subscription only

- Provider: Elsevier

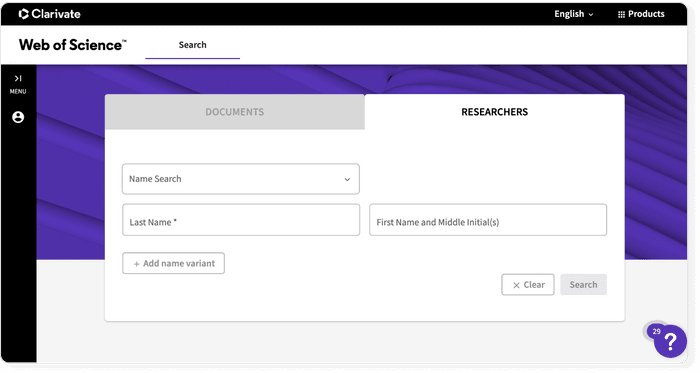

Web of Science also known as Web of Knowledge is the second big bibliographic database. Usually, academic institutions provide either access to Web of Science or Scopus on their campus network for free.

- Coverage: approx. 100 million items

- References: 1.4 billion

- Access options: institutional subscription only

- Provider: Clarivate (formerly Thomson Reuters)

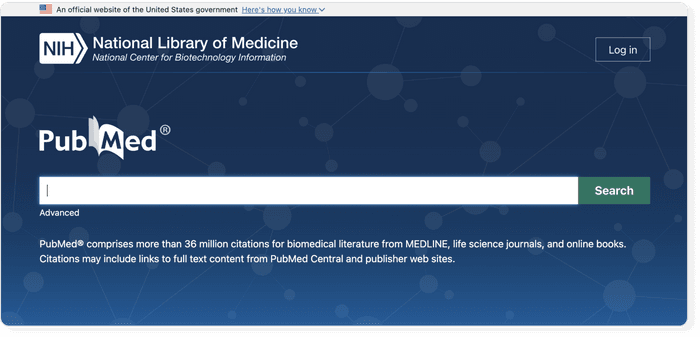

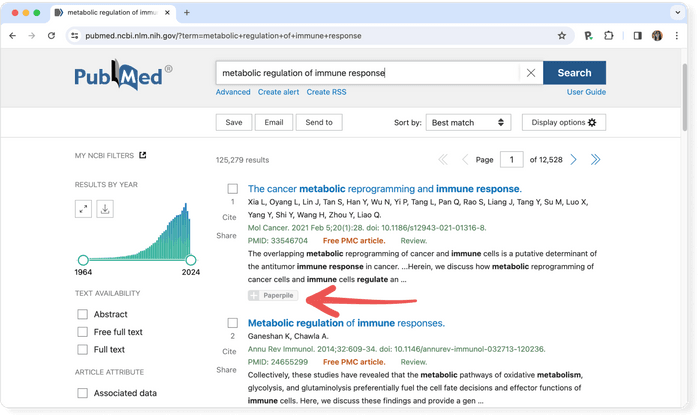

PubMed is the number one resource for anyone looking for literature in medicine or biological sciences. PubMed stores abstracts and bibliographic details of more than 30 million papers and provides full text links to the publisher sites or links to the free PDF on PubMed Central (PMC) .

- Coverage: approx. 35 million items

- Discipline: Medicine and Biological Sciences

- Access options: free

- Provider: NIH

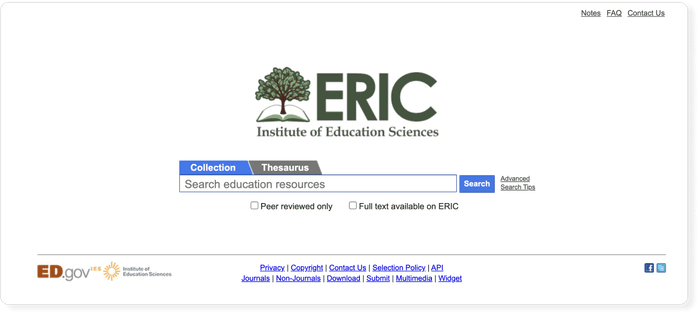

For education sciences, ERIC is the number one destination. ERIC stands for Education Resources Information Center, and is a database that specifically hosts education-related literature.

- Coverage: approx. 1.6 million items

- Discipline: Education

- Provider: U.S. Department of Education

IEEE Xplore is the leading academic database in the field of engineering and computer science. It's not only journal articles, but also conference papers, standards and books that can be search for.

- Coverage: approx. 6 million items

- Discipline: Engineering

- Provider: IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers)

ScienceDirect is the gateway to the millions of academic articles published by Elsevier, 1.4 million of which are open access. Journals and books can be searched via a single interface.

- Coverage: approx. 19.5 million items

The DOAJ is an open-access academic database that can be accessed and searched for free.

- Coverage: over 8 million records

- Provider: DOAJ

JSTOR is another great resource to find research papers. Any article published before 1924 in the United States is available for free and JSTOR also offers scholarships for independent researchers.

- Coverage: more than 12 million items

- Provider: ITHAKA

Start using a reference manager like Paperpile to save, organize, and cite your references. Paperpile integrates with PubMed and many popular databases, so you can save references and PDFs directly to your library using the Paperpile buttons:

Scopus is one of the two big commercial, bibliographic databases that cover scholarly literature from almost any discipline. Beside searching for research articles, Scopus also provides academic journal rankings, author profiles, and an h-index calculator .

PubMed is the number one resource for anyone looking for literature in medicine or biological sciences. PubMed stores abstracts and bibliographic details of more than 30 million papers and provides full text links to the publisher sites or links to the free PDF on PubMed Central (PMC)

is Mainsite

- Search all IEEE websites

- Mission and vision

- IEEE at a glance

- IEEE Strategic Plan

- Organization of IEEE

- Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion

- Organizational Ethics

- Annual Report

- History of IEEE

- Volunteer resources

- IEEE Corporate Awards Program

- Financials and Statistics

- IEEE Future Directions

- IEEE for Industry (Corporations, Government, Individuals)

IEEE Climate Change

- Humanitarian and Philanthropic Opportunities

- Select an option

- Get the latest news

- Access volunteer resources (Code of Ethics, financial forms, tools and templates, and more)

- Find IEEE locations

- Get help from the IEEE Support Center

- Recover your IEEE Account username and password

- Learn about the IEEE Awards program and submit nomination

- View IEEE's organizational structure and leadership

- Apply for jobs at IEEE

- See the history of IEEE

- Learn more about Diversity, Equity & Inclusion at IEEE

- Join an IEEE Society

- Renew your membership

- Member benefits

- IEEE Contact Center

- Connect locally

- Memberships and Subscriptions Catalog

- Member insurance and discounts

- Member Grade Elevation

- Get your company engaged

- Access your Account

- Learn about membership dues

- Learn about Women in Engineering (WIE)

- Access IEEE member email

- Find information on IEEE Fellows

- Access the IEEE member directory

- Learn about the Member-Get-a-Member program

- Learn about IEEE Potentials magazine

- Learn about Student membership

- Affinity groups

- IEEE Societies

- Technical Councils

- Technical Communities

- Geographic Activities

- Working groups

- IEEE Regions

- IEEE Collabratec®

- IEEE Resource Centers

IEEE DataPort

- See the IEEE Regions

- View the MGA Operations Manual

- Find information on IEEE Technical Activities

- Get IEEE Chapter resources

- Find IEEE Sections, Chapters, Student Branches, and other communities

- Learn how to create an IEEE Student Chapter

- Upcoming conferences

- IEEE Meetings, Conferences & Events (MCE)

- IEEE Conference Application

- IEEE Conference Organizer Education Program

- See benefits of authoring a conference paper

- Search for 2025 conferences

- Search for 2024 conferences

- Find conference organizer resources

- Register a conference

- Publish conference papers

- Manage conference finances

- Learn about IEEE Meetings, Conferences & Events (MCE)

- Visit the IEEE SA site

- Become a member of the IEEE SA

- Find information on the IEEE Registration Authority

- Obtain a MAC, OUI, or Ethernet address

- Access the IEEE 802.11™ WLAN standard

- Purchase standards

- Get free select IEEE standards

- Purchase standards subscriptions on IEEE Xplore®

- Get involved with standards development

- Find a working group

- Find information on IEEE 802.11™

- Access the National Electrical Safety Code® (NESC®)

- Find MAC, OUI, and Ethernet addresses from Registration Authority (regauth)

- Get free IEEE standards

- Learn more about the IEEE Standards Association

- View Software and Systems Engineering Standards

- IEEE Xplore® Digital Library

- Subscription options

- IEEE Spectrum

- The Institute

Proceedings of the IEEE

- IEEE Access®

- Author resources

- Get an IEEE Xplore Digital Library trial for IEEE members

- Review impact factors of IEEE journals

- Request access to the IEEE Thesaurus and Taxonomy

- Access the IEEE copyright form

- Find article templates in Word and LaTeX formats

- Get author education resources

- Visit the IEEE Xplore digital library

- Find Author Digital Tools for IEEE paper submission

- Review the IEEE plagiarism policy

- Get information about all stages of publishing with IEEE

- IEEE Learning Network (ILN)

- IEEE Credentialing Program

- Pre-university

- IEEE-Eta Kappa Nu

- Accreditation

- Access continuing education courses on the IEEE Learning Network

- Find STEM education resources on TryEngineering.org

- Learn about the TryEngineering Summer Institute for high school students

- Explore university education program resources

- Access pre-university STEM education resources

- Learn about IEEE certificates and how to offer them

- Find information about the IEEE-Eta Kappa Nu honor society

- Learn about resources for final-year engineering projects

- Access career resources

Publications

Ieee provides a wide range of quality publications that make the exchange of technical knowledge and information possible among technology professionals..

Expand All | Collapse All

- > Get an IEEE Xplore Digital Library trial for IEEE members

- > Review impact factors of IEEE journals

- > Access the IEEE thesaurus and taxonomy

- > Find article templates in Word and LaTeX formats

- > Get author education resources

- > Visit the IEEE Xplore Digital Library

- > Learn more about IEEE author tools

- > Review the IEEE plagiarism policy

- > Get information about all stages of publishing with IEEE

Why choose IEEE publications?

IEEE publishes the leading journals, transactions, letters, and magazines in electrical engineering, computing, biotechnology, telecommunications, power and energy, and dozens of other technologies.

In addition, IEEE publishes more than 1,800 leading-edge conference proceedings every year, which are recognized by academia and industry worldwide as the most vital collection of consolidated published papers in electrical engineering, computer science, and related fields.

Spotlight on IEEE publications

Ieee xplore ®.

- About IEEE Xplore

- Visit the IEEE Xplore Digital Library

- See how to purchase articles and standards

- Find support and training

- Browse popular content

- Sign up for a free trial

IEEE Spectrum Magazine

- Visit the IEEE Spectrum website

- Visit the Institute for IEEE member news

IEEE Access

- Visit IEEE Access

- See recent issues

Benefits of publishing

Authors: why publish with ieee.

- PSPB Accomplishments in 2023 (PDF, 228 KB)

- IEEE statement of support for Open Science

- IEEE signs San Francisco Declaration on Research Assessment (DORA)

- Read about how IEEE journals maintain top citation rankings

Open Access Solutions

- Visit IEEE Open

Visit the IEEE Author Center

Find author resources >

- > IEEE Collabratec ®

- > Choosing a journal

- > Writing

- > Author Tools

- > How to Publish with IEEE (English) (PPT, 3 MB)

- > How to Publish with IEEE (Chinese) (PPT, 3 MB)

- > Benefits of Publishing with IEEE (PPT, 7 MB)

- > View author tutorial videos

- Read the IEEE statement on appropriate use of bibliometric indicators

Publication types and subscription options

- Journal and magazine subscriptions

- Digital library subscriptions

- Buy individual articles from IEEE Xplore

For organizations:

- Browse IEEE subscriptions

- Get institutional access

- Subscribe through your local IEEE account manager

Publishing information

IEEE publishing makes the exchange of technical knowledge possible with the highest quality and the greatest impact.

- Open access publishing options

- Intellectual Property Rights (IPR)

- Reprints of articles

- Services for IEEE organizations

Contact information

- Contact IEEE Publications

- About the Publication Services & Products Board

Related Information >

Network. collaborate. create with ieee collabratec®..

All within one central hub—with exclusive features for IEEE members.

- Experience IEEE Collabratec

Join/Renew IEEE or a Society

Receive member access to select content, product discounts, and more.

- Review all member benefits

Try this easy-to-use, globally accessible data repository that provides significant benefits to researchers, data analysts, and the global technical community.

- Start learning today

IEEE is committed to helping combat and mitigate the effects of climate change.

- See what's new on the IEEE Climate Change site

- Corrections

Search Help

Get the most out of Google Scholar with some helpful tips on searches, email alerts, citation export, and more.

Finding recent papers

Your search results are normally sorted by relevance, not by date. To find newer articles, try the following options in the left sidebar:

- click "Since Year" to show only recently published papers, sorted by relevance;

- click "Sort by date" to show just the new additions, sorted by date;

- click the envelope icon to have new results periodically delivered by email.

Locating the full text of an article

Abstracts are freely available for most of the articles. Alas, reading the entire article may require a subscription. Here're a few things to try:

- click a library link, e.g., "FindIt@Harvard", to the right of the search result;

- click a link labeled [PDF] to the right of the search result;

- click "All versions" under the search result and check out the alternative sources;

- click "Related articles" or "Cited by" under the search result to explore similar articles.

If you're affiliated with a university, but don't see links such as "FindIt@Harvard", please check with your local library about the best way to access their online subscriptions. You may need to do search from a computer on campus, or to configure your browser to use a library proxy.

Getting better answers

If you're new to the subject, it may be helpful to pick up the terminology from secondary sources. E.g., a Wikipedia article for "overweight" might suggest a Scholar search for "pediatric hyperalimentation".

If the search results are too specific for your needs, check out what they're citing in their "References" sections. Referenced works are often more general in nature.

Similarly, if the search results are too basic for you, click "Cited by" to see newer papers that referenced them. These newer papers will often be more specific.

Explore! There's rarely a single answer to a research question. Click "Related articles" or "Cited by" to see closely related work, or search for author's name and see what else they have written.

Searching Google Scholar

Use the "author:" operator, e.g., author:"d knuth" or author:"donald e knuth".

Put the paper's title in quotations: "A History of the China Sea".

You'll often get better results if you search only recent articles, but still sort them by relevance, not by date. E.g., click "Since 2018" in the left sidebar of the search results page.

To see the absolutely newest articles first, click "Sort by date" in the sidebar. If you use this feature a lot, you may also find it useful to setup email alerts to have new results automatically sent to you.

Note: On smaller screens that don't show the sidebar, these options are available in the dropdown menu labelled "Year" right below the search button.

Select the "Case law" option on the homepage or in the side drawer on the search results page.

It finds documents similar to the given search result.

It's in the side drawer. The advanced search window lets you search in the author, title, and publication fields, as well as limit your search results by date.

Select the "Case law" option and do a keyword search over all jurisdictions. Then, click the "Select courts" link in the left sidebar on the search results page.

Tip: To quickly search a frequently used selection of courts, bookmark a search results page with the desired selection.

Access to articles

For each Scholar search result, we try to find a version of the article that you can read. These access links are labelled [PDF] or [HTML] and appear to the right of the search result. For example:

A paper that you need to read

Access links cover a wide variety of ways in which articles may be available to you - articles that your library subscribes to, open access articles, free-to-read articles from publishers, preprints, articles in repositories, etc.

When you are on a campus network, access links automatically include your library subscriptions and direct you to subscribed versions of articles. On-campus access links cover subscriptions from primary publishers as well as aggregators.

Off-campus access

Off-campus access links let you take your library subscriptions with you when you are at home or traveling. You can read subscribed articles when you are off-campus just as easily as when you are on-campus. Off-campus access links work by recording your subscriptions when you visit Scholar while on-campus, and looking up the recorded subscriptions later when you are off-campus.

We use the recorded subscriptions to provide you with the same subscribed access links as you see on campus. We also indicate your subscription access to participating publishers so that they can allow you to read the full-text of these articles without logging in or using a proxy. The recorded subscription information expires after 30 days and is automatically deleted.

In addition to Google Scholar search results, off-campus access links can also appear on articles from publishers participating in the off-campus subscription access program. Look for links labeled [PDF] or [HTML] on the right hand side of article pages.

Anne Author , John Doe , Jane Smith , Someone Else

In this fascinating paper, we investigate various topics that would be of interest to you. We also describe new methods relevant to your project, and attempt to address several questions which you would also like to know the answer to. Lastly, we analyze …

You can disable off-campus access links on the Scholar settings page . Disabling off-campus access links will turn off recording of your library subscriptions. It will also turn off indicating subscription access to participating publishers. Once off-campus access links are disabled, you may need to identify and configure an alternate mechanism (e.g., an institutional proxy or VPN) to access your library subscriptions while off-campus.

Email Alerts

Do a search for the topic of interest, e.g., "M Theory"; click the envelope icon in the sidebar of the search results page; enter your email address, and click "Create alert". We'll then periodically email you newly published papers that match your search criteria.

No, you can enter any email address of your choice. If the email address isn't a Google account or doesn't match your Google account, then we'll email you a verification link, which you'll need to click to start receiving alerts.

This works best if you create a public profile , which is free and quick to do. Once you get to the homepage with your photo, click "Follow" next to your name, select "New citations to my articles", and click "Done". We will then email you when we find new articles that cite yours.

Search for the title of your paper, e.g., "Anti de Sitter space and holography"; click on the "Cited by" link at the bottom of the search result; and then click on the envelope icon in the left sidebar of the search results page.

First, do a search for your colleague's name, and see if they have a Scholar profile. If they do, click on it, click the "Follow" button next to their name, select "New articles by this author", and click "Done".

If they don't have a profile, do a search by author, e.g., [author:s-hawking], and click on the mighty envelope in the left sidebar of the search results page. If you find that several different people share the same name, you may need to add co-author names or topical keywords to limit results to the author you wish to follow.

We send the alerts right after we add new papers to Google Scholar. This usually happens several times a week, except that our search robots meticulously observe holidays.

There's a link to cancel the alert at the bottom of every notification email.

If you created alerts using a Google account, you can manage them all here . If you're not using a Google account, you'll need to unsubscribe from the individual alerts and subscribe to the new ones.

Google Scholar library

Google Scholar library is your personal collection of articles. You can save articles right off the search page, organize them by adding labels, and use the power of Scholar search to quickly find just the one you want - at any time and from anywhere. You decide what goes into your library, and we’ll keep the links up to date.

You get all the goodies that come with Scholar search results - links to PDF and to your university's subscriptions, formatted citations, citing articles, and more!

Library help

Find the article you want to add in Google Scholar and click the “Save” button under the search result.

Click “My library” at the top of the page or in the side drawer to view all articles in your library. To search the full text of these articles, enter your query as usual in the search box.

Find the article you want to remove, and then click the “Delete” button under it.

- To add a label to an article, find the article in your library, click the “Label” button under it, select the label you want to apply, and click “Done”.

- To view all the articles with a specific label, click the label name in the left sidebar of your library page.

- To remove a label from an article, click the “Label” button under it, deselect the label you want to remove, and click “Done”.

- To add, edit, or delete labels, click “Manage labels” in the left column of your library page.

Only you can see the articles in your library. If you create a Scholar profile and make it public, then the articles in your public profile (and only those articles) will be visible to everyone.

Your profile contains all the articles you have written yourself. It’s a way to present your work to others, as well as to keep track of citations to it. Your library is a way to organize the articles that you’d like to read or cite, not necessarily the ones you’ve written.

Citation Export

Click the "Cite" button under the search result and then select your bibliography manager at the bottom of the popup. We currently support BibTeX, EndNote, RefMan, and RefWorks.

Err, no, please respect our robots.txt when you access Google Scholar using automated software. As the wearers of crawler's shoes and webmaster's hat, we cannot recommend adherence to web standards highly enough.

Sorry, we're unable to provide bulk access. You'll need to make an arrangement directly with the source of the data you're interested in. Keep in mind that a lot of the records in Google Scholar come from commercial subscription services.

Sorry, we can only show up to 1,000 results for any particular search query. Try a different query to get more results.

Content Coverage

Google Scholar includes journal and conference papers, theses and dissertations, academic books, pre-prints, abstracts, technical reports and other scholarly literature from all broad areas of research. You'll find works from a wide variety of academic publishers, professional societies and university repositories, as well as scholarly articles available anywhere across the web. Google Scholar also includes court opinions and patents.

We index research articles and abstracts from most major academic publishers and repositories worldwide, including both free and subscription sources. To check current coverage of a specific source in Google Scholar, search for a sample of their article titles in quotes.

While we try to be comprehensive, it isn't possible to guarantee uninterrupted coverage of any particular source. We index articles from sources all over the web and link to these websites in our search results. If one of these websites becomes unavailable to our search robots or to a large number of web users, we have to remove it from Google Scholar until it becomes available again.

Our meticulous search robots generally try to index every paper from every website they visit, including most major sources and also many lesser known ones.

That said, Google Scholar is primarily a search of academic papers. Shorter articles, such as book reviews, news sections, editorials, announcements and letters, may or may not be included. Untitled documents and documents without authors are usually not included. Website URLs that aren't available to our search robots or to the majority of web users are, obviously, not included either. Nor do we include websites that require you to sign up for an account, install a browser plugin, watch four colorful ads, and turn around three times and say coo-coo before you can read the listing of titles scanned at 10 DPI... You get the idea, we cover academic papers from sensible websites.

That's usually because we index many of these papers from other websites, such as the websites of their primary publishers. The "site:" operator currently only searches the primary version of each paper.

It could also be that the papers are located on examplejournals.gov, not on example.gov. Please make sure you're searching for the "right" website.

That said, the best way to check coverage of a specific source is to search for a sample of their papers using the title of the paper.

Ahem, we index papers, not journals. You should also ask about our coverage of universities, research groups, proteins, seminal breakthroughs, and other dimensions that are of interest to users. All such questions are best answered by searching for a statistical sample of papers that has the property of interest - journal, author, protein, etc. Many coverage comparisons are available if you search for [allintitle:"google scholar"], but some of them are more statistically valid than others.

Currently, Google Scholar allows you to search and read published opinions of US state appellate and supreme court cases since 1950, US federal district, appellate, tax and bankruptcy courts since 1923 and US Supreme Court cases since 1791. In addition, it includes citations for cases cited by indexed opinions or journal articles which allows you to find influential cases (usually older or international) which are not yet online or publicly available.

Legal opinions in Google Scholar are provided for informational purposes only and should not be relied on as a substitute for legal advice from a licensed lawyer. Google does not warrant that the information is complete or accurate.

We normally add new papers several times a week. However, updates to existing records take 6-9 months to a year or longer, because in order to update our records, we need to first recrawl them from the source website. For many larger websites, the speed at which we can update their records is limited by the crawl rate that they allow.

Inclusion and Corrections

We apologize, and we assure you the error was unintentional. Automated extraction of information from articles in diverse fields can be tricky, so an error sometimes sneaks through.

Please write to the owner of the website where the erroneous search result is coming from, and encourage them to provide correct bibliographic data to us, as described in the technical guidelines . Once the data is corrected on their website, it usually takes 6-9 months to a year or longer for it to be updated in Google Scholar. We appreciate your help and your patience.

If you can't find your papers when you search for them by title and by author, please refer your publisher to our technical guidelines .

You can also deposit your papers into your institutional repository or put their PDF versions on your personal website, but please follow your publisher's requirements when you do so. See our technical guidelines for more details on the inclusion process.

We normally add new papers several times a week; however, it might take us some time to crawl larger websites, and corrections to already included papers can take 6-9 months to a year or longer.

Google Scholar generally reflects the state of the web as it is currently visible to our search robots and to the majority of users. When you're searching for relevant papers to read, you wouldn't want it any other way!

If your citation counts have gone down, chances are that either your paper or papers that cite it have either disappeared from the web entirely, or have become unavailable to our search robots, or, perhaps, have been reformatted in a way that made it difficult for our automated software to identify their bibliographic data and references. If you wish to correct this, you'll need to identify the specific documents with indexing problems and ask your publisher to fix them. Please refer to the technical guidelines .

Please do let us know . Please include the URL for the opinion, the corrected information and a source where we can verify the correction.

We're only able to make corrections to court opinions that are hosted on our own website. For corrections to academic papers, books, dissertations and other third-party material, click on the search result in question and contact the owner of the website where the document came from. For corrections to books from Google Book Search, click on the book's title and locate the link to provide feedback at the bottom of the book's page.

General Questions

These are articles which other scholarly articles have referred to, but which we haven't found online. To exclude them from your search results, uncheck the "include citations" box on the left sidebar.

First, click on links labeled [PDF] or [HTML] to the right of the search result's title. Also, check out the "All versions" link at the bottom of the search result.

Second, if you're affiliated with a university, using a computer on campus will often let you access your library's online subscriptions. Look for links labeled with your library's name to the right of the search result's title. Also, see if there's a link to the full text on the publisher's page with the abstract.

Keep in mind that final published versions are often only available to subscribers, and that some articles are not available online at all. Good luck!

Technically, your web browser remembers your settings in a "cookie" on your computer's disk, and sends this cookie to our website along with every search. Check that your browser isn't configured to discard our cookies. Also, check if disabling various proxies or overly helpful privacy settings does the trick. Either way, your settings are stored on your computer, not on our servers, so a long hard look at your browser's preferences or internet options should help cure the machine's forgetfulness.

Not even close. That phrase is our acknowledgement that much of scholarly research involves building on what others have already discovered. It's taken from Sir Isaac Newton's famous quote, "If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants."

- Privacy & Terms

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2020

- Volume 36 , pages 909–913, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Clara Busse ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0178-1000 1 &

- Ella August ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5151-1036 1 , 2

279k Accesses

15 Citations

709 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Communicating research findings is an essential step in the research process. Often, peer-reviewed journals are the forum for such communication, yet many researchers are never taught how to write a publishable scientific paper. In this article, we explain the basic structure of a scientific paper and describe the information that should be included in each section. We also identify common pitfalls for each section and recommend strategies to avoid them. Further, we give advice about target journal selection and authorship. In the online resource 1 , we provide an example of a high-quality scientific paper, with annotations identifying the elements we describe in this article.

Similar content being viewed by others

How to Choose the Right Journal

The Point Is…to Publish?

Writing and publishing a scientific paper

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Writing a scientific paper is an important component of the research process, yet researchers often receive little formal training in scientific writing. This is especially true in low-resource settings. In this article, we explain why choosing a target journal is important, give advice about authorship, provide a basic structure for writing each section of a scientific paper, and describe common pitfalls and recommendations for each section. In the online resource 1 , we also include an annotated journal article that identifies the key elements and writing approaches that we detail here. Before you begin your research, make sure you have ethical clearance from all relevant ethical review boards.

Select a Target Journal Early in the Writing Process

We recommend that you select a “target journal” early in the writing process; a “target journal” is the journal to which you plan to submit your paper. Each journal has a set of core readers and you should tailor your writing to this readership. For example, if you plan to submit a manuscript about vaping during pregnancy to a pregnancy-focused journal, you will need to explain what vaping is because readers of this journal may not have a background in this topic. However, if you were to submit that same article to a tobacco journal, you would not need to provide as much background information about vaping.

Information about a journal’s core readership can be found on its website, usually in a section called “About this journal” or something similar. For example, the Journal of Cancer Education presents such information on the “Aims and Scope” page of its website, which can be found here: https://www.springer.com/journal/13187/aims-and-scope .

Peer reviewer guidelines from your target journal are an additional resource that can help you tailor your writing to the journal and provide additional advice about crafting an effective article [ 1 ]. These are not always available, but it is worth a quick web search to find out.

Identify Author Roles Early in the Process

Early in the writing process, identify authors, determine the order of authors, and discuss the responsibilities of each author. Standard author responsibilities have been identified by The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) [ 2 ]. To set clear expectations about each team member’s responsibilities and prevent errors in communication, we also suggest outlining more detailed roles, such as who will draft each section of the manuscript, write the abstract, submit the paper electronically, serve as corresponding author, and write the cover letter. It is best to formalize this agreement in writing after discussing it, circulating the document to the author team for approval. We suggest creating a title page on which all authors are listed in the agreed-upon order. It may be necessary to adjust authorship roles and order during the development of the paper. If a new author order is agreed upon, be sure to update the title page in the manuscript draft.

In the case where multiple papers will result from a single study, authors should discuss who will author each paper. Additionally, authors should agree on a deadline for each paper and the lead author should take responsibility for producing an initial draft by this deadline.

Structure of the Introduction Section

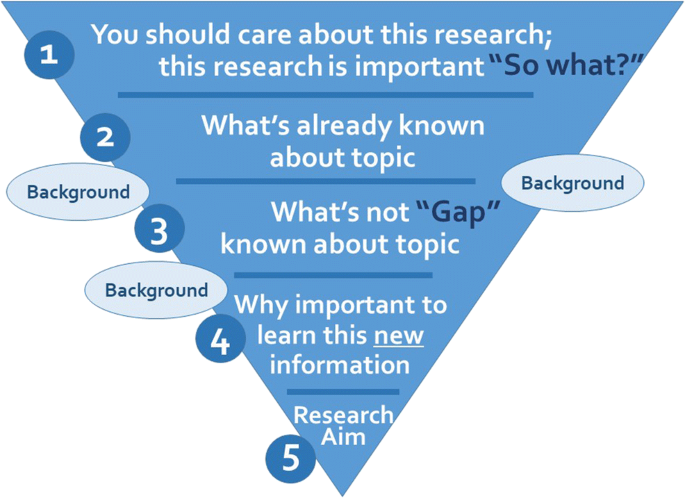

The introduction section should be approximately three to five paragraphs in length. Look at examples from your target journal to decide the appropriate length. This section should include the elements shown in Fig. 1 . Begin with a general context, narrowing to the specific focus of the paper. Include five main elements: why your research is important, what is already known about the topic, the “gap” or what is not yet known about the topic, why it is important to learn the new information that your research adds, and the specific research aim(s) that your paper addresses. Your research aim should address the gap you identified. Be sure to add enough background information to enable readers to understand your study. Table 1 provides common introduction section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

The main elements of the introduction section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Methods Section

The purpose of the methods section is twofold: to explain how the study was done in enough detail to enable its replication and to provide enough contextual detail to enable readers to understand and interpret the results. In general, the essential elements of a methods section are the following: a description of the setting and participants, the study design and timing, the recruitment and sampling, the data collection process, the dataset, the dependent and independent variables, the covariates, the analytic approach for each research objective, and the ethical approval. The hallmark of an exemplary methods section is the justification of why each method was used. Table 2 provides common methods section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Results Section

The focus of the results section should be associations, or lack thereof, rather than statistical tests. Two considerations should guide your writing here. First, the results should present answers to each part of the research aim. Second, return to the methods section to ensure that the analysis and variables for each result have been explained.

Begin the results section by describing the number of participants in the final sample and details such as the number who were approached to participate, the proportion who were eligible and who enrolled, and the number of participants who dropped out. The next part of the results should describe the participant characteristics. After that, you may organize your results by the aim or by putting the most exciting results first. Do not forget to report your non-significant associations. These are still findings.

Tables and figures capture the reader’s attention and efficiently communicate your main findings [ 3 ]. Each table and figure should have a clear message and should complement, rather than repeat, the text. Tables and figures should communicate all salient details necessary for a reader to understand the findings without consulting the text. Include information on comparisons and tests, as well as information about the sample and timing of the study in the title, legend, or in a footnote. Note that figures are often more visually interesting than tables, so if it is feasible to make a figure, make a figure. To avoid confusing the reader, either avoid abbreviations in tables and figures, or define them in a footnote. Note that there should not be citations in the results section and you should not interpret results here. Table 3 provides common results section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Discussion Section

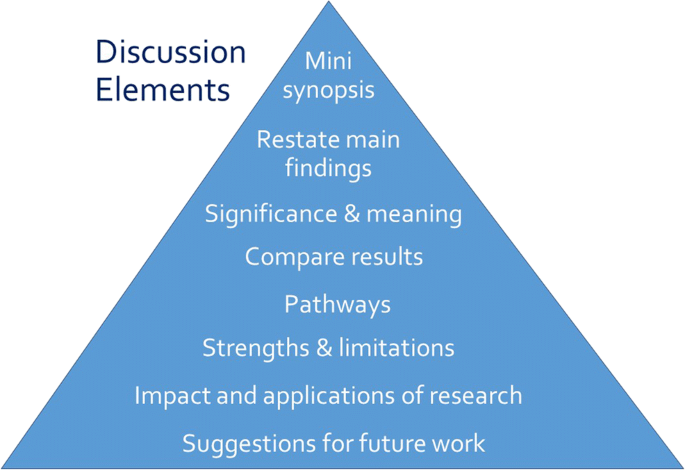

Opposite the introduction section, the discussion should take the form of a right-side-up triangle beginning with interpretation of your results and moving to general implications (Fig. 2 ). This section typically begins with a restatement of the main findings, which can usually be accomplished with a few carefully-crafted sentences.

Major elements of the discussion section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Next, interpret the meaning or explain the significance of your results, lifting the reader’s gaze from the study’s specific findings to more general applications. Then, compare these study findings with other research. Are these findings in agreement or disagreement with those from other studies? Does this study impart additional nuance to well-accepted theories? Situate your findings within the broader context of scientific literature, then explain the pathways or mechanisms that might give rise to, or explain, the results.

Journals vary in their approach to strengths and limitations sections: some are embedded paragraphs within the discussion section, while some mandate separate section headings. Keep in mind that every study has strengths and limitations. Candidly reporting yours helps readers to correctly interpret your research findings.

The next element of the discussion is a summary of the potential impacts and applications of the research. Should these results be used to optimally design an intervention? Does the work have implications for clinical protocols or public policy? These considerations will help the reader to further grasp the possible impacts of the presented work.

Finally, the discussion should conclude with specific suggestions for future work. Here, you have an opportunity to illuminate specific gaps in the literature that compel further study. Avoid the phrase “future research is necessary” because the recommendation is too general to be helpful to readers. Instead, provide substantive and specific recommendations for future studies. Table 4 provides common discussion section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Follow the Journal’s Author Guidelines

After you select a target journal, identify the journal’s author guidelines to guide the formatting of your manuscript and references. Author guidelines will often (but not always) include instructions for titles, cover letters, and other components of a manuscript submission. Read the guidelines carefully. If you do not follow the guidelines, your article will be sent back to you.

Finally, do not submit your paper to more than one journal at a time. Even if this is not explicitly stated in the author guidelines of your target journal, it is considered inappropriate and unprofessional.

Your title should invite readers to continue reading beyond the first page [ 4 , 5 ]. It should be informative and interesting. Consider describing the independent and dependent variables, the population and setting, the study design, the timing, and even the main result in your title. Because the focus of the paper can change as you write and revise, we recommend you wait until you have finished writing your paper before composing the title.

Be sure that the title is useful for potential readers searching for your topic. The keywords you select should complement those in your title to maximize the likelihood that a researcher will find your paper through a database search. Avoid using abbreviations in your title unless they are very well known, such as SNP, because it is more likely that someone will use a complete word rather than an abbreviation as a search term to help readers find your paper.

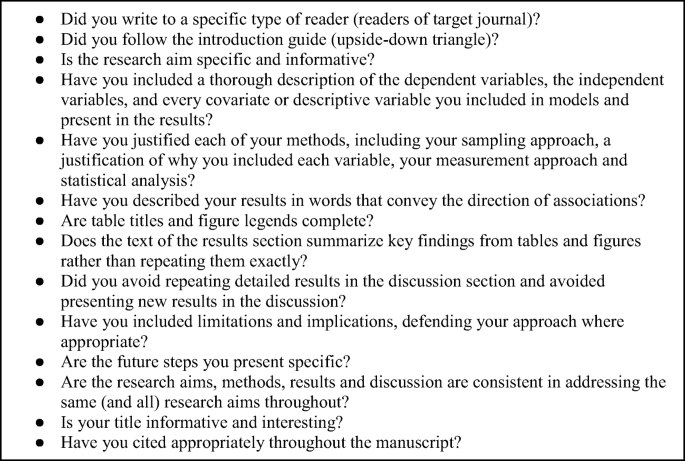

After you have written a complete draft, use the checklist (Fig. 3 ) below to guide your revisions and editing. Additional resources are available on writing the abstract and citing references [ 5 ]. When you feel that your work is ready, ask a trusted colleague or two to read the work and provide informal feedback. The box below provides a checklist that summarizes the key points offered in this article.

Checklist for manuscript quality

Data Availability

Michalek AM (2014) Down the rabbit hole…advice to reviewers. J Cancer Educ 29:4–5

Article Google Scholar

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Defining the role of authors and contributors: who is an author? http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authosrs-and-contributors.html . Accessed 15 January, 2020

Vetto JT (2014) Short and sweet: a short course on concise medical writing. J Cancer Educ 29(1):194–195

Brett M, Kording K (2017) Ten simple rules for structuring papers. PLoS ComputBiol. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005619

Lang TA (2017) Writing a better research article. J Public Health Emerg. https://doi.org/10.21037/jphe.2017.11.06

Download references

Acknowledgments

Ella August is grateful to the Sustainable Sciences Institute for mentoring her in training researchers on writing and publishing their research.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Maternal and Child Health, University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health, 135 Dauer Dr, 27599, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Clara Busse & Ella August

Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109-2029, USA

Ella August

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ella August .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interests.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 362 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Busse, C., August, E. How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal. J Canc Educ 36 , 909–913 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

Download citation

Published : 30 April 2020

Issue Date : October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Manuscripts

- Scientific writing

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

“The only truly modern academic research engine”

Oa.mg is a search engine for academic papers, specialising in open access. we have over 250 million papers in our index..

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

Clara busse.

1 Department of Maternal and Child Health, University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health, 135 Dauer Dr, 27599 Chapel Hill, NC USA

Ella August

2 Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2029 USA

Associated Data

Communicating research findings is an essential step in the research process. Often, peer-reviewed journals are the forum for such communication, yet many researchers are never taught how to write a publishable scientific paper. In this article, we explain the basic structure of a scientific paper and describe the information that should be included in each section. We also identify common pitfalls for each section and recommend strategies to avoid them. Further, we give advice about target journal selection and authorship. In the online resource 1 , we provide an example of a high-quality scientific paper, with annotations identifying the elements we describe in this article.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

Writing a scientific paper is an important component of the research process, yet researchers often receive little formal training in scientific writing. This is especially true in low-resource settings. In this article, we explain why choosing a target journal is important, give advice about authorship, provide a basic structure for writing each section of a scientific paper, and describe common pitfalls and recommendations for each section. In the online resource 1 , we also include an annotated journal article that identifies the key elements and writing approaches that we detail here. Before you begin your research, make sure you have ethical clearance from all relevant ethical review boards.

Select a Target Journal Early in the Writing Process

We recommend that you select a “target journal” early in the writing process; a “target journal” is the journal to which you plan to submit your paper. Each journal has a set of core readers and you should tailor your writing to this readership. For example, if you plan to submit a manuscript about vaping during pregnancy to a pregnancy-focused journal, you will need to explain what vaping is because readers of this journal may not have a background in this topic. However, if you were to submit that same article to a tobacco journal, you would not need to provide as much background information about vaping.

Information about a journal’s core readership can be found on its website, usually in a section called “About this journal” or something similar. For example, the Journal of Cancer Education presents such information on the “Aims and Scope” page of its website, which can be found here: https://www.springer.com/journal/13187/aims-and-scope .

Peer reviewer guidelines from your target journal are an additional resource that can help you tailor your writing to the journal and provide additional advice about crafting an effective article [ 1 ]. These are not always available, but it is worth a quick web search to find out.

Identify Author Roles Early in the Process

Early in the writing process, identify authors, determine the order of authors, and discuss the responsibilities of each author. Standard author responsibilities have been identified by The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) [ 2 ]. To set clear expectations about each team member’s responsibilities and prevent errors in communication, we also suggest outlining more detailed roles, such as who will draft each section of the manuscript, write the abstract, submit the paper electronically, serve as corresponding author, and write the cover letter. It is best to formalize this agreement in writing after discussing it, circulating the document to the author team for approval. We suggest creating a title page on which all authors are listed in the agreed-upon order. It may be necessary to adjust authorship roles and order during the development of the paper. If a new author order is agreed upon, be sure to update the title page in the manuscript draft.

In the case where multiple papers will result from a single study, authors should discuss who will author each paper. Additionally, authors should agree on a deadline for each paper and the lead author should take responsibility for producing an initial draft by this deadline.

Structure of the Introduction Section

The introduction section should be approximately three to five paragraphs in length. Look at examples from your target journal to decide the appropriate length. This section should include the elements shown in Fig. 1 . Begin with a general context, narrowing to the specific focus of the paper. Include five main elements: why your research is important, what is already known about the topic, the “gap” or what is not yet known about the topic, why it is important to learn the new information that your research adds, and the specific research aim(s) that your paper addresses. Your research aim should address the gap you identified. Be sure to add enough background information to enable readers to understand your study. Table Table1 1 provides common introduction section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

The main elements of the introduction section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Common introduction section pitfalls and recommendations

| Pitfall | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Introduction is too generic, not written to specific readers of a designated journal. | Visit your target journal’s website and investigate the journal’s readership. If you are writing for a journal with a more general readership, like PLOS ONE, you should include more background information. A narrower journal, like the Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association, may require less background information because most of its readers have expertise in the subject matter. |

| Citations are inadequate to support claims. | If a claim could be debated, it should be supported by one or more citations. To find articles relevant to your research, consider using open-access journals, which are available for anyone to read for free. A list of open-access journals can be found here: . You can also find open-access articles using PubMed Central: |

| The research aim is vague. | Be sure that your research aim contains essential details like the setting, population/sample, study design, timing, dependent variable, and independent variables. Using such details, the reader should be able to imagine the analysis you have conducted. |

Methods Section

The purpose of the methods section is twofold: to explain how the study was done in enough detail to enable its replication and to provide enough contextual detail to enable readers to understand and interpret the results. In general, the essential elements of a methods section are the following: a description of the setting and participants, the study design and timing, the recruitment and sampling, the data collection process, the dataset, the dependent and independent variables, the covariates, the analytic approach for each research objective, and the ethical approval. The hallmark of an exemplary methods section is the justification of why each method was used. Table Table2 2 provides common methods section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Common methods section pitfalls and recommendations

| Pitfall | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| The author only describes methods for one study aim, or part of an aim. |

Be sure to check that the methods describe all aspects of the study reported in the manuscript. |

| There is not enough (or any) justification for the methods used. | You must justify your choice of methods because it greatly impacts the interpretation of results. State the methods you used and then defend those decisions. For example, justify why you chose to include the measurements, covariates, and statistical approaches. |

Results Section

The focus of the results section should be associations, or lack thereof, rather than statistical tests. Two considerations should guide your writing here. First, the results should present answers to each part of the research aim. Second, return to the methods section to ensure that the analysis and variables for each result have been explained.

Begin the results section by describing the number of participants in the final sample and details such as the number who were approached to participate, the proportion who were eligible and who enrolled, and the number of participants who dropped out. The next part of the results should describe the participant characteristics. After that, you may organize your results by the aim or by putting the most exciting results first. Do not forget to report your non-significant associations. These are still findings.

Tables and figures capture the reader’s attention and efficiently communicate your main findings [ 3 ]. Each table and figure should have a clear message and should complement, rather than repeat, the text. Tables and figures should communicate all salient details necessary for a reader to understand the findings without consulting the text. Include information on comparisons and tests, as well as information about the sample and timing of the study in the title, legend, or in a footnote. Note that figures are often more visually interesting than tables, so if it is feasible to make a figure, make a figure. To avoid confusing the reader, either avoid abbreviations in tables and figures, or define them in a footnote. Note that there should not be citations in the results section and you should not interpret results here. Table Table3 3 provides common results section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Common results section pitfalls and recommendations

| Pitfall | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| The text focuses on statistical tests rather than associations. | The relationships between independent and dependent variables are at the heart of scientific studies and statistical tests are a set of strategies used to elucidate such relationships. For example, instead of reporting that “the odds ratio is 3.4,” report that “women with exposure X were 3.4 times more likely to have disease Y.” There are several ways to express such associations, but all successful approaches focus on the relationships between the variables. |

| Causal words like “cause” and “impact” are used inappropriately | Only some study designs and analytic approaches enable researchers to make causal claims. Before you use the word “cause,” consider whether this is justified given your design. Words like “associated” or “related” may be more appropriate. |

| The direction of association unclear. |

Instead of “X is associated with Y,” say “an increase in variable X is associated with a decrease in variable Y,” a sentence which more fully describes the relationship between the two variables. |

Discussion Section

Opposite the introduction section, the discussion should take the form of a right-side-up triangle beginning with interpretation of your results and moving to general implications (Fig. 2 ). This section typically begins with a restatement of the main findings, which can usually be accomplished with a few carefully-crafted sentences.

Major elements of the discussion section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Next, interpret the meaning or explain the significance of your results, lifting the reader’s gaze from the study’s specific findings to more general applications. Then, compare these study findings with other research. Are these findings in agreement or disagreement with those from other studies? Does this study impart additional nuance to well-accepted theories? Situate your findings within the broader context of scientific literature, then explain the pathways or mechanisms that might give rise to, or explain, the results.

Journals vary in their approach to strengths and limitations sections: some are embedded paragraphs within the discussion section, while some mandate separate section headings. Keep in mind that every study has strengths and limitations. Candidly reporting yours helps readers to correctly interpret your research findings.

The next element of the discussion is a summary of the potential impacts and applications of the research. Should these results be used to optimally design an intervention? Does the work have implications for clinical protocols or public policy? These considerations will help the reader to further grasp the possible impacts of the presented work.

Finally, the discussion should conclude with specific suggestions for future work. Here, you have an opportunity to illuminate specific gaps in the literature that compel further study. Avoid the phrase “future research is necessary” because the recommendation is too general to be helpful to readers. Instead, provide substantive and specific recommendations for future studies. Table Table4 4 provides common discussion section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Common discussion section pitfalls and recommendations

| Pitfall | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| The author repeats detailed results or presents new results in the discussion section. | Recall from Fig. that the discussion section should take the shape of a triangle as it moves from a specific restatement of the main findings to a broader discussion of the scientific literature and implications of the study. Specific values should not be repeated in the discussion. It is also not appropriate to include new results in the discussion section. |

| The author fails to describe the implication of the study’s limitations. | No matter how well-conducted and thoughtful, all studies have limitations. Candidly describe how the limitations affect the application of the findings. |

| Statements about future research are too generic. | Is the relationship between exposure and outcome not well-described in a population that is severely impacted? Or might there be another variable that modifies the relationship between exposure and outcome? This is your opportunity to suggest areas requiring further study in your field, steering scientific inquiry toward the most meaningful questions. |

Follow the Journal’s Author Guidelines

After you select a target journal, identify the journal’s author guidelines to guide the formatting of your manuscript and references. Author guidelines will often (but not always) include instructions for titles, cover letters, and other components of a manuscript submission. Read the guidelines carefully. If you do not follow the guidelines, your article will be sent back to you.

Finally, do not submit your paper to more than one journal at a time. Even if this is not explicitly stated in the author guidelines of your target journal, it is considered inappropriate and unprofessional.

Your title should invite readers to continue reading beyond the first page [ 4 , 5 ]. It should be informative and interesting. Consider describing the independent and dependent variables, the population and setting, the study design, the timing, and even the main result in your title. Because the focus of the paper can change as you write and revise, we recommend you wait until you have finished writing your paper before composing the title.

Be sure that the title is useful for potential readers searching for your topic. The keywords you select should complement those in your title to maximize the likelihood that a researcher will find your paper through a database search. Avoid using abbreviations in your title unless they are very well known, such as SNP, because it is more likely that someone will use a complete word rather than an abbreviation as a search term to help readers find your paper.

After you have written a complete draft, use the checklist (Fig. (Fig.3) 3 ) below to guide your revisions and editing. Additional resources are available on writing the abstract and citing references [ 5 ]. When you feel that your work is ready, ask a trusted colleague or two to read the work and provide informal feedback. The box below provides a checklist that summarizes the key points offered in this article.

Checklist for manuscript quality

(PDF 362 kb)

Acknowledgments

Ella August is grateful to the Sustainable Sciences Institute for mentoring her in training researchers on writing and publishing their research.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Data Availability

Compliance with ethical standards.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Happiness Hub Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- Happiness Hub

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

- Research Papers

How to Write and Publish Your Research in a Journal

Last Updated: May 26, 2024 Fact Checked

Choosing a Journal

Writing the research paper, editing & revising your paper, submitting your paper, navigating the peer review process, research paper help.

This article was co-authored by Matthew Snipp, PhD and by wikiHow staff writer, Cheyenne Main . C. Matthew Snipp is the Burnet C. and Mildred Finley Wohlford Professor of Humanities and Sciences in the Department of Sociology at Stanford University. He is also the Director for the Institute for Research in the Social Science’s Secure Data Center. He has been a Research Fellow at the U.S. Bureau of the Census and a Fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences. He has published 3 books and over 70 articles and book chapters on demography, economic development, poverty and unemployment. He is also currently serving on the National Institute of Child Health and Development’s Population Science Subcommittee. He holds a Ph.D. in Sociology from the University of Wisconsin—Madison. There are 13 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 704,617 times.

Publishing a research paper in a peer-reviewed journal allows you to network with other scholars, get your name and work into circulation, and further refine your ideas and research. Before submitting your paper, make sure it reflects all the work you’ve done and have several people read over it and make comments. Keep reading to learn how you can choose a journal, prepare your work for publication, submit it, and revise it after you get a response back.

Things You Should Know

- Create a list of journals you’d like to publish your work in and choose one that best aligns with your topic and your desired audience.

- Prepare your manuscript using the journal’s requirements and ask at least 2 professors or supervisors to review your paper.

- Write a cover letter that “sells” your manuscript, says how your research adds to your field and explains why you chose the specific journal you’re submitting to.

- Ask your professors or supervisors for well-respected journals that they’ve had good experiences publishing with and that they read regularly.

- Many journals also only accept specific formats, so by choosing a journal before you start, you can write your article to their specifications and increase your chances of being accepted.

- If you’ve already written a paper you’d like to publish, consider whether your research directly relates to a hot topic or area of research in the journals you’re looking into.

- Review the journal’s peer review policies and submission process to see if you’re comfortable creating or adjusting your work according to their standards.

- Open-access journals can increase your readership because anyone can access them.

- Scientific research papers: Instead of a “thesis,” you might write a “research objective” instead. This is where you state the purpose of your research.

- “This paper explores how George Washington’s experiences as a young officer may have shaped his views during difficult circumstances as a commanding officer.”

- “This paper contends that George Washington’s experiences as a young officer on the 1750s Pennsylvania frontier directly impacted his relationship with his Continental Army troops during the harsh winter at Valley Forge.”

- Scientific research papers: Include a “materials and methods” section with the step-by-step process you followed and the materials you used. [5] X Research source

- Read other research papers in your field to see how they’re written. Their format, writing style, subject matter, and vocabulary can help guide your own paper. [6] X Research source

- If you’re writing about George Washington’s experiences as a young officer, you might emphasize how this research changes our perspective of the first president of the U.S.

- Link this section to your thesis or research objective.

- If you’re writing a paper about ADHD, you might discuss other applications for your research.

- Scientific research papers: You might include your research and/or analytical methods, your main findings or results, and the significance or implications of your research.

- Try to get as many people as you can to read over your abstract and provide feedback before you submit your paper to a journal.

- They might also provide templates to help you structure your manuscript according to their specific guidelines. [11] X Research source

- Not all journal reviewers will be experts on your specific topic, so a non-expert “outsider’s perspective” can be valuable.

- If you have a paper on the purification of wastewater with fungi, you might use both the words “fungi” and “mushrooms.”

- Use software like iThenticate, Turnitin, or PlagScan to check for similarities between the submitted article and published material available online. [15] X Research source

- Header: Address the editor who will be reviewing your manuscript by their name, include the date of submission, and the journal you are submitting to.

- First paragraph: Include the title of your manuscript, the type of paper it is (like review, research, or case study), and the research question you wanted to answer and why.

- Second paragraph: Explain what was done in your research, your main findings, and why they are significant to your field.

- Third paragraph: Explain why the journal’s readers would be interested in your work and why your results are important to your field.

- Conclusion: State the author(s) and any journal requirements that your work complies with (like ethical standards”).

- “We confirm that this manuscript has not been published elsewhere and is not under consideration by another journal.”

- “All authors have approved the manuscript and agree with its submission to [insert the name of the target journal].”

- Submit your article to only one journal at a time.

- When submitting online, use your university email account. This connects you with a scholarly institution, which can add credibility to your work.

- Accept: Only minor adjustments are needed, based on the provided feedback by the reviewers. A first submission will rarely be accepted without any changes needed.

- Revise and Resubmit: Changes are needed before publication can be considered, but the journal is still very interested in your work.

- Reject and Resubmit: Extensive revisions are needed. Your work may not be acceptable for this journal, but they might also accept it if significant changes are made.

- Reject: The paper isn’t and won’t be suitable for this publication, but that doesn’t mean it might not work for another journal.

- Try organizing the reviewer comments by how easy it is to address them. That way, you can break your revisions down into more manageable parts.

- If you disagree with a comment made by a reviewer, try to provide an evidence-based explanation when you resubmit your paper.

- If you’re resubmitting your paper to the same journal, include a point-by-point response paper that talks about how you addressed all of the reviewers’ comments in your revision. [22] X Research source

- If you’re not sure which journal to submit to next, you might be able to ask the journal editor which publications they recommend.

Expert Q&A

You might also like.

- If reviewers suspect that your submitted manuscript plagiarizes another work, they may refer to a Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) flowchart to see how to move forward. [23] X Research source Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- ↑ https://www.wiley.com/en-us/network/publishing/research-publishing/choosing-a-journal/6-steps-to-choosing-the-right-journal-for-your-research-infographic

- ↑ https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

- ↑ https://libguides.unomaha.edu/c.php?g=100510&p=651627

- ↑ https://www.canberra.edu.au/library/start-your-research/research_help/publishing-research

- ↑ https://writingcenter.fas.harvard.edu/conclusions

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/assignments/writing-an-abstract-for-your-research-paper/

- ↑ https://www.springer.com/gp/authors-editors/book-authors-editors/your-publication-journey/manuscript-preparation

- ↑ https://apus.libanswers.com/writing/faq/2391

- ↑ https://academicguides.waldenu.edu/library/keyword/search-strategy

- ↑ https://ifis.libguides.com/journal-publishing-guide/submitting-your-paper

- ↑ https://www.springer.com/kr/authors-editors/authorandreviewertutorials/submitting-to-a-journal-and-peer-review/cover-letters/10285574

- ↑ https://www.apa.org/monitor/sep02/publish.aspx

- ↑ Matthew Snipp, PhD. Research Fellow, U.S. Bureau of the Census. Expert Interview. 26 March 2020.

About This Article

To publish a research paper, ask a colleague or professor to review your paper and give you feedback. Once you've revised your work, familiarize yourself with different academic journals so that you can choose the publication that best suits your paper. Make sure to look at the "Author's Guide" so you can format your paper according to the guidelines for that publication. Then, submit your paper and don't get discouraged if it is not accepted right away. You may need to revise your paper and try again. To learn about the different responses you might get from journals, see our reviewer's explanation below. Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

RAMDEV GOHIL

Oct 16, 2017

Did this article help you?

David Okandeji

Oct 23, 2019

Revati Joshi

Feb 13, 2017

Shahzad Khan

Jul 1, 2017

Apr 7, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

Little-known secrets for how to get published

Advice from seasoned psychologists for those seeking to publish in a journal for the first time

By Rebecca A. Clay

January 2019, Vol 50, No. 1

Print version: page 64

- Peer Review

An academic who is trying to get a journal article published is a lot like a salmon swimming upstream, says Dana S. Dunn, PhD, a member of APA’s Board of Educational Affairs. “The most important thing is persistence,” says Dunn, a psychology professor at Moravian College in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

But there are ways to make the journey through the publication process (see The publication process ) easier. “The more work you do up front, the more you can ensure a good outcome,” says Dunn. Among other tasks, that means finding the right venue, crafting the best possible manuscript and not giving up when asked to revise a manuscript.

The Monitor spoke with Dunn and several other senior faculty members with extensive experience publishing articles and serving as journal editors and editorial board members. Here’s their advice.

■ Target the right journals. To find the journal that’s the best fit for your article, research the journals themselves. Check each target journal’s mission statement, ask colleagues who have published there if your work is appropriate for it and read a current issue to see the kinds of articles it contains. “If your work isn’t in line with what they publish, they will reject it out of hand and you will have wasted valuable time,” says Dunn.