- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

English Civil Wars

By: History.com Editors

Updated: September 10, 2021 | Original: December 2, 2009

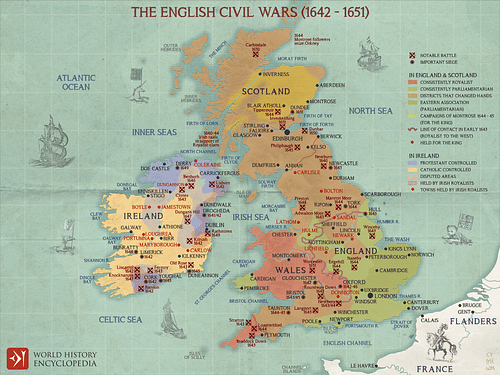

Between 1642 and 1651, armies loyal to King Charles I and Parliament faced off in three civil wars over longstanding disputes about religious freedom and how the “three kingdoms” of England, Scotland and Ireland should be governed. Notable outcomes of the wars included the execution of King Charles I in 1649, 11 years of republican rule in England and the establishment of Britain’s first standing national army.

Background: The Rise of the Stuarts and King Charles I

England’s last Tudor monarch, Elizabeth I , died in 1603, and was succeeded by her cousin, James Stuart . Already King James VI of Scotland, he became King James I of England and Ireland as well, uniting the three kingdoms under a single ruler for the first time. Though at first the Catholic minority in England welcomed James’ ascension to the throne, they later turned against his regime, even attempting to blow up the king and Parliament in the Gunpowder Plot .

James’ son, Charles I, succeeded him on the throne in 1625. His marriage to a Catholic princess, Henrietta Maria of France fueled suspicions (especially among more radical Protestants, known as Puritans ) that the king would introduce Catholic traditions back into the Church of England. Charles also believed strongly in his divine right to rule, and in 1629 he dismissed Parliament altogether; he would not recall it for the next 11 years.

War in Scotland

Beginning in the late 1630s, Charles made efforts to establish a more English-like religious practice in Scotland, generating fierce resistance among that country’s Presbyterian majority. A Scottish army defeated Charles’ forces and invaded England, forcing Charles to recall Parliament in 1640 to generate the money to pay his own troops and settle the conflict. Instead, Parliament acted quickly to restrict the king’s powers, even ordering the trial and execution of one of his chief ministers, Lord Strafford.

Amid the political upheaval in London, the Catholic majority in Ireland rebelled, massacring hundreds of Protestants there in October 1641. Tales of the violence inflamed tensions in England, as Charles and Parliament disagreed on how to respond. In January 1642, the king tried and failed to arrest five members of Parliament who opposed him. Fearing for his own safety, Charles fled London for northern England, where he called on his supporters to prepare for war.

Did you know? In May 1660, nearly 20 years after the start of the English Civil Wars, Charles II finally returned to England as king, ushering in a period known as the Restoration.

First English Civil War (1642-46)

When civil war broke out in earnest in August 1642, Royalist forces (known as Cavaliers) controlled northern and western England, while Parliamentarians (or Roundheads) dominated in the southern and eastern regions of the country. The king’s forces appeared to be gaining the upper hand by early 1643, especially after concluding an alliance with Irish Catholics to end the Irish Rebellion. But a key alliance between the Parliamentarians and Scotland that year led to a large Scottish army joining the fray on Parliament’s side in January 1644.

On July 2, 1644, Royalist and Parliamentarian forces met at Marston Moor, west of York, in the largest battle of the First English Civil War. A Parliamentarian force of 28,000 routed the smaller Royalist army of 18,000 , ending the king’s control of northern England. In 1645, Parliament created a permanent, professional, trained army of 22,000 men. This New Model Army, commanded by Sir Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell , scored a decisive victory in June 1645 in the Battle of Naseby, effectively dooming the Royalist cause.

Second English Civil War (1648-49) and execution of King Charles I

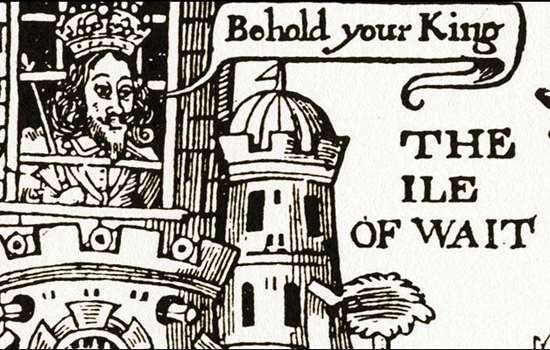

Even in defeat, Charles refused to give in, but sought to capitalize on the religious and political divisions among his enemies. While on the Isle of Wight in 1647-48, the king managed to conclude a peace treaty with the Scots and marshal Royalist sentiment and discontent with Parliament into a series of armed uprisings across England in the spring and summer of 1648.

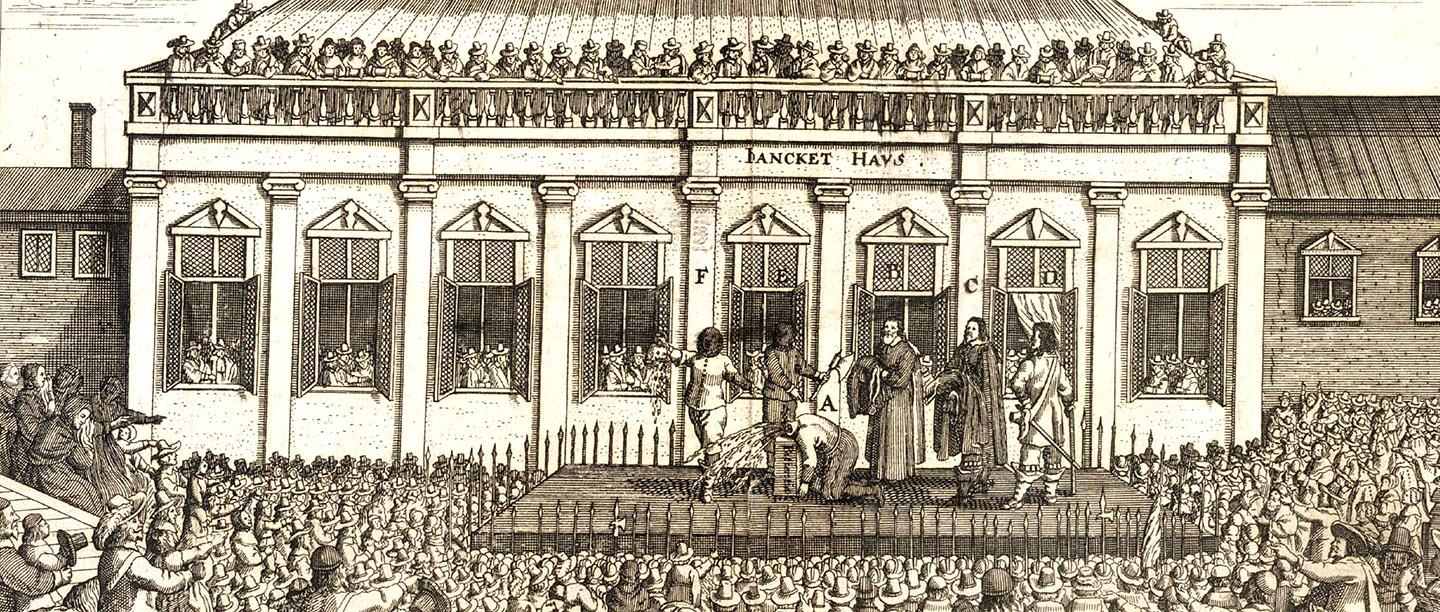

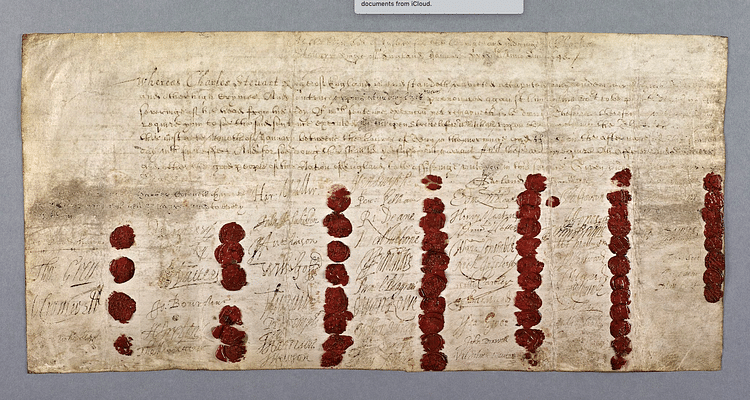

After Fairfax, Cromwell and the New Model Army easily crushed the Royalist uprisings, hard-line opponents of the king took charge of a smaller Parliament. Concluding that peace could not be reached while Charles was still alive, they set up a high court and put the king on trial for treason. Charles was found guilty and executed by beheading on January 30, 1649 at Whitehall.

Third English Civil War (1649-51)

With Charles dead, a republican regime was established in England, backed by the military might of the New Model Army. Beginning late in 1649, Cromwell led his army in a successful reconquest of Ireland, including the notorious massacre of thousands of Irish and Royalist troops and civilians at Drogheda. Meanwhile, Scotland came to an agreement with the executed king’s eldest son, also named Charles, who was crowned King Charles II of Scotland in early 1651.

Even before he was officially crowned, Charles II had formed an army of English and Scottish Royalists, prompting Cromwell to invade Scotland in 1650. After losing the Battle of Dunbar to Cromwell’s forces in September 1650, Charles led an invasion of England the following year, only to suffer another defeat against a huge Parliamentarian army at Worcester. The young king narrowly escaped capture, but the decisive victory ended the Third English Civil War, along with the larger War of the Three Kingdoms (England, Scotland and Ireland).

Impact of the Civil Wars

An estimated 200,000 English soldiers and civilians were killed during the three civil wars, by fighting and the disease spread by armies; the loss was proportionate, population-wise, to that of World War I.

In 1653, Oliver Cromwell was installed as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland, and tried (largely unsuccessfully) to consolidate broad support behind the new republican regime amid the continued growth of radical religious sects and widespread uneasiness about the new standing army.

After Cromwell’s death in 1658, he was succeeded as protector by his son Richard, who abdicated just eight months later. With the continued disintegration of the republic, the larger Parliament was reassembled, and began negotiations with Charles II to resume the throne. The triumphant king arrived in London in May 1660, beginning the English Restoration .

British Civil Wars. National Army Museum .

Mark Stoyle. Overview: Civil War and Revolution, 1603-1714. BBC .

The English Civil Wars: Origins, events and legacy. English Heritage .

Simon Jenkins. A Short History of England: The Glorious Story of a Rowdy Nation . (PublicAffairs, 2011)

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Personal Rule and the seeds of rebellion (1629–40)

The bishops’ wars and the return of parliament (1640–42).

- The first English Civil War (1642–46)

- Conflicts in Scotland and Ireland

- Second and third English Civil Wars (1648–51)

- Cost and legacy

- What is Charles I known for?

- What was Charles I’s early life like?

- How did Charles I become king of Great Britain and Ireland?

- What was the relationship between Charles I and Parliament like?

- Why was Charles I executed?

English Civil Wars

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- National Center for Biotechnology Information - PubMed Central - Misogyny, feminism, and sexual harassment

- World History Encyclopedia - English Civil Wars

- NSCC Libraries Pressbooks - Western Civilization: A Concise History - The English Civil War and the Glorious Revolution

- History Learning Site - The English Civil War

- The Cormwwell Association - Causes of the English Civil War

- English Civil War - Children's Encyclopedia (Ages 8-11)

- English Civil Wars - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

- Table Of Contents

When did the English Civil Wars occur?

The English Civil Wars occurred from 1642 through 1651. The fighting during this period is traditionally broken into three wars: the first happened from 1642 to 1646, the second in 1648, and the third from 1650 to 1651.

What was the first major battle fought in the English Civil Wars?

The first major battle of the English Civil Wars fought on English soil was the Battle of Edgehill , which occurred in October 1642. Forces loyal to the English Parliament, commanded by Robert Devereux, 3rd earl of Essex , delayed Charles I’s march on London.

How many people died during the English Civil Wars?

An estimated 200,000 people lost their lives directly or indirectly as a result of the English Civil Wars, making it arguably the bloodiest conflict in the history of the British Isles.

When did the English Civil Wars come to an end?

The English Civil Wars ended on September 3, 1651, with Oliver Cromwell ’s victory at Worcester and the subsequent flight of Charles II to France.

English Civil Wars , (1642–51), fighting that took place in the British Isles between supporters of the monarchy of Charles I (and his son and successor , Charles II ) and opposing groups in each of Charles’s kingdoms, including Parliamentarians in England , Covenanters in Scotland , and Confederates in Ireland . The English Civil Wars are traditionally considered to have begun in England in August 1642, when Charles I raised an army against the wishes of Parliament , ostensibly to deal with a rebellion in Ireland. But the period of conflict actually began earlier in Scotland, with the Bishops’ Wars of 1639–40, and in Ireland, with the Ulster rebellion of 1641. Throughout the 1640s, war between king and Parliament ravaged England, but it also struck all of the kingdoms held by the house of Stuart —and, in addition to war between the various British and Irish dominions, there was civil war within each of the Stuart states. For this reason the English Civil Wars might more properly be called the British Civil Wars or the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. The wars finally ended in 1651 with the flight of Charles II to France and, with him, the hopes of the British monarchy.

Compared with the chaos unleashed by the Thirty Years’ War (1618–48) on the European continent, the British Isles under Charles I enjoyed relative peace and economic prosperity during the 1630s. However, by the later 1630s, Charles’s regime had become unpopular across a broad front throughout his kingdoms. During the period of his so-called Personal Rule (1629–40), known by his enemies as the “Eleven-Year Tyranny” because he had dissolved Parliament and ruled by decree, Charles had resorted to dubious fiscal expedients, most notably “ ship money ,” an annual levy for the reform of the navy that in 1635 was extended from English ports to inland towns. This inclusion of inland towns was construed as a new tax without parliamentary authorization. When combined with ecclesiastical reforms undertaken by Charles’s close adviser William Laud , the archbishop of Canterbury , and with the conspicuous role assumed in these reforms by Henrietta Maria , Charles’s Catholic queen, and her courtiers, many in England became alarmed. Nevertheless, despite grumblings, there is little doubt that had Charles managed to rule his other dominions as he controlled England, his peaceful reign might have been extended indefinitely. Scotland and Ireland proved his undoing.

In 1633 Thomas Wentworth became lord deputy of Ireland and set out to govern that country without regard for any interest but that of the crown. His thorough policies aimed to make Ireland financially self-sufficient; to enforce religious conformity with the Church of England as defined by Laud, Wentworth’s close friend and ally; to “civilize” the Irish; and to extend royal control throughout Ireland by establishing British plantations and challenging Irish titles to land. Wentworth’s actions alienated both the Protestant and the Catholic ruling elites in Ireland. In much the same way, Charles’s willingness to tamper with Scottish land titles unnerved landowners there. However, it was Charles’s attempt in 1637 to introduce a modified version of the English Book of Common Prayer that provoked a wave of riots in Scotland, beginning at the Church of St. Giles in Edinburgh . A National Covenant calling for immediate withdrawal of the prayer book was speedily drawn up on February 28, 1638. Despite its moderate tone and conservative format, the National Covenant was a radical manifesto against the Personal Rule of Charles I that justified a revolt against the interfering sovereign .

The turn of events in Scotland horrified Charles, who determined to bring the rebellious Scots to heel. However, the Covenanters , as the Scottish rebels became known, quickly overwhelmed the poorly trained English army, forcing the king to sign a peace treaty at Berwick (June 18, 1639). Though the Covenanters had won the first Bishops’ War , Charles refused to concede victory and called an English parliament, seeing it as the only way to raise money quickly. Parliament assembled in April 1640, but it lasted only three weeks (and hence became known as the Short Parliament ). The House of Commons was willing to vote the huge sums that the king needed to finance his war against the Scots, but not until their grievances—some dating back more than a decade—had been redressed. Furious, Charles precipitately dissolved the Short Parliament. As a result, it was an untrained, ill-armed, and poorly paid force that trailed north to fight the Scots in the second Bishops’ War. On August 20, 1640, the Covenanters invaded England for the second time, and in a spectacular military campaign they took Newcastle following the Battle of Newburn (August 28). Demoralized and humiliated, the king had no alternative but to negotiate and, at the insistence of the Scots, to recall parliament.

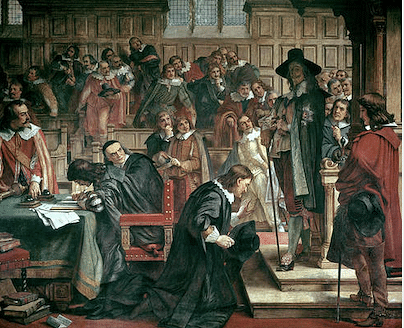

A new parliament (the Long Parliament ), which no one dreamed would sit for the next 20 years, assembled at Westminster on November 3, 1640, and immediately called for the impeachment of Wentworth, who by now was the earl of Strafford. The lengthy trial at Westminster, ending with Strafford’s execution on May 12, 1641, was orchestrated by Protestants and Catholics from Ireland, by Scottish Covenanters, and by the king’s English opponents, especially the leader of Commons, John Pym —effectively highlighting the importance of the connections between all the Stuart kingdoms at this critical junction.

To some extent, the removal of Strafford’s draconian hand facilitated the outbreak in October 1641 of the Ulster uprising in Ireland. This rebellion derived, on the one hand, from long-term social, religious, and economic causes (namely tenurial insecurity, economic instability, indebtedness, and a desire to have the Roman Catholic Church restored to its pre- Reformation position) and, on the other hand, from short-term political factors that triggered the outbreak of violence. Inevitably, bloodshed and unnecessary cruelty accompanied the insurrection, which quickly engulfed the island and took the form of a popular rising, pitting Catholic natives against Protestant newcomers. The extent of the “massacre” of Protestants was exaggerated, especially in England where the wildest rumours were readily believed. Perhaps 4,000 settlers lost their lives—a tragedy to be sure, but a far cry from the figure of 154,000 the Irish government suggested had been butchered. Much more common was the plundering and pillaging of Protestant property and the theft of livestock. These human and material losses were replicated on the Catholic side as the Protestants retaliated.

The Irish insurrection immediately precipitated a political crisis in England, as Charles and his Westminster Parliament argued over which of them should control the army to be raised to quell the Irish insurgents. Had Charles accepted the list of grievances presented to him by Parliament in the Grand Remonstrance of December 1641 and somehow reconciled their differences, the revolt in Ireland almost certainly would have been quashed with relative ease. Instead, Charles mobilized for war on his own, raising his standard at Nottingham in August 1642. The Wars of the Three Kingdoms had begun in earnest. This also marked the onset of the first English Civil War fought between forces loyal to Charles I and those who served Parliament. After a period of phony war late in 1642, the basic shape of the English Civil War was of Royalist advance in 1643 and then steady Parliamentarian attrition and expansion.

English Heritage

- https://www.facebook.com/englishheritage

- https://twitter.com/englishheritage

- https://www.youtube.com/user/EnglishHeritageFilm

- https://instagram.com/englishheritage

The English Civil Wars: History and Stories

The English Civil Wars were a catastrophic series of conflicts that took place in the middle of the 17th century. Fought between those loyal to the king, Charles I, and those loyal to Parliament, the wars divided the country at all levels of society. At the heart of the conflict were fundamental questions about power and religion.

The legacy of the Civil Wars can be seen not only in our political landscape, but in the historic environment. Many of the ruined castles we see today sustained their damage during the war. Learn more about the Civil Wars, the people who lived through them, and how the conflict unfolded at English Heritage sites.

- The English Civil Wars comprised three wars, which were fought between Charles I and Parliament between 1642 and 1651.

- The wars were part of a wider conflict involving Wales, Scotland and Ireland, known as the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

- The human cost of the wars was devastating. Up to 200,000 people lost their lives, or 4.5% of the population. This was as great a loss, proportionally, as during the First World War.

- The causes of the wars were complex and many-layered. At the centre of the conflict were disagreements about religion, and discontent over the king’s use of power and his economic policies.

- In 1649, the victorious Parliamentarians sentenced Charles I to death. His execution resulted in the only period of republican rule in British history, during which military leader Oliver Cromwell ruled as Lord Protector of the Commonwealth. This period is known as the Interregnum, and lasted for 11 years until 1660 when Charles’s son, Charles II, was restored to the throne.

- The Civil Wars saw the beginning of the modern British Army tradition with the creation of the New Model Army – the country’s first national army, comprised of trained, professional soldiers.

- Many castles were besieged during the wars, resulting in severe damage. Others were deliberately destroyed, or ‘slighted’, after the fighting. The ruinous state of many of England’s castles that we see today can be traced back to these events.

The Civil Wars Explained

Journey through one the most complex and turbulent periods in English history with our comprehensive guide to the events of the Civil Wars.

We look at what caused the wars, how they unfolded, and what their legacy was – from their origins in the early years of Charles I’s reign to Parliament’s short-lived victory and the subsequent Restoration of the monarchy.

Key Figures and Stories

Read about the man at the centre of the most turbulent period of England’s history, and learn about the statue dedicated to him in Trafalgar Square, London.

A Royal Prisoner at Carisbrooke Castle

Read about Charles I’s time as a prisoner at Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight, including his many attempts to escape.

Jane Whorwood: Royalist Spy

Jane Whorwood was one of the key agents behind attempts to free Charles I from captivity on the Isle of Wight, notably from Carisbrooke Castle, in 1648.

Charles II and the Royal Oak

Find out how the future king escaped from Parliamentarian forces after the Battle of Worcester in 1651, giving English history one of its greatest adventure stories.

The Battle of the Downs

This major sea battle between the Dutch and the Spanish in 1639 exposed the weakness of the English navy. Read more about the battle and how it destabilised Charles I’s reign in the years running up to the first Civil War.

The Civil Wars and the British Army

Discover how the reorganisation of the Parliamentarian army during the Civil Wars marked the beginning of the modern British Army tradition.

Living Through War

To live in the middle of the 17th century was to endure some of British history’s most distressing and divisive events. Discover just some of the people associated with our properties who lived through them, and how they carried on with their lives and professions.

Margaret Cavendish

Novelist, poet and philosopher Margaret Cavendish travelled to Paris with Queen Henrietta Maria to escape the violence of the Civil Wars, and remained in exile there throughout the Interregnum. Against the backdrop of this political upheaval, she wrote prolifically on sex, gender, and natural and political philosophy.

Lady Anne Clifford

In 1649 Lady Anne Clifford, a staunch Royalist, left London to reclaim her family estates in northern England. Finding her lands badly neglected and the five Clifford castles much damaged by the events of the Civil Wars, she devoted the final three decades of her life to restoring them.

John Dryden

Poet John Dryden briefly served in Cromwell’s government and on his death commemorated him in ‘Heroic Stanzas’. After the Restoration, however, his loyalties shifted and he wrote several long poems praising Charles II. The king later officially employed Dryden as Poet Laureate. Read more about the poet and where to find his London blue plaque.

Samuel Pepys

Diarist Samuel Pepys witnessed Charles I’s execution as a 15-year-old boy. He held Republican sympathies that day, but, like Dryden, he swiftly adopted Royalist loyalties once Charles II was restored to the throne. It was to Pepys that Charles II recounted his dramatic escape from Boscobel House. Read more about the famous chronicler, and discover his London blue plaque.

Castles Under Siege

Discover the places in English Heritage’s care that were besieged during the wars.

Discover how Donnington Castle in Berkshire held out for King Charles I during a 20-month siege in 1644–6, and played a key role in the Second Battle of Newbury.

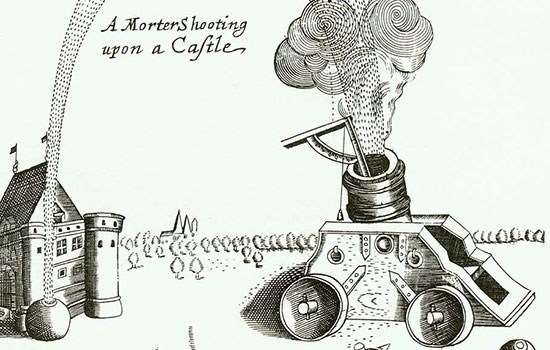

In 1646 Goodrich Castle was the scene of one of the most hard-fought sieges of the first Civil War, which Parliament finally won with the aid of a huge mortar, known as Roaring Meg.

Old Wardour

In 1643 Lady Blanche Arundell defended Old Wardour against Parliamentarian attack for six days before being forced to surrender. Read more about the siege and the castle’s fate after the wars.

Scarborough

Scarborough Castle was besieged twice during the Civil Wars, and during one of them, the bombardment was so intense that half the tower collapsed. Read about the sieges, and more of the castle’s history, here.

In 1646 Pendennis was one of the last Royalist strongholds to hold out against the Parliamentarian army. About 1,000 soldiers and their dependants endured a five-month siege, only surrendering when their food supplies ran out.

Beeston Castle passed between Royalist and Parliamentarian hands several times during the Civil Wars. The Royalists finally surrendered in 1645, and the castle was slighted.

War came to Walmer in 1648, while Charles I was imprisoned. In Kent, a rebellion broke out in support of the king. Sailors from the English navy in the Downs captured Sandown, Deal and Walmer castles, but all were eventually recaptured by Parliament.

Walmer’s neighbour, Deal Castle, also saw battle in 1648, and held out against a ferocious siege for nearly three months before finally succumbing to Parliament. Read more about Deal’s history.

Explore More

Boscobel House

Explore the history of Boscobel House, where Charles II hid while fleeing Parliamentarian soldiers in 1651.

White Ladies Priory

Read about Boscobel’s sister site, where Charles II first arrived after his flight from the battle of Worcester. It was here that he adopted his disguise as a peasant, and plotted his escape.

Cromwell’s Castle

Standing on a rocky promontory in the Scilly Isles, this round tower was built after Parliament’s conquest of the Scillies in 1651 and is one of the few surviving Cromwellian fortifications in Britain. Read more about its history.

Life under siege at Goodrich Castle

The 17th-century objects found at Goodrich Castle help us to imagine what life at the castle was like during the Civil War siege. View some of them in detail here.

English Civil Wars

Server costs fundraiser 2024.

The English Civil Wars (1642-1651) witnessed a bitter conflict between Royalists ('Cavaliers') and Parliamentarians ('Roundheads'). The Royalists supported first King Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649) and then his son Charles II, while the Parliamentarians, the ultimate victors, wanted to diminish the constitutional powers of the monarchy and prevent what they considered a Catholic-inspired plot to reverse the English Reformation .

Parliament, led by such figures as Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658), had superior resources and a more professional fighting force – the New Model Army – which ensured the Royalists ultimately lost the three civil wars fought in England , Ireland , and Scotland (hence the alternative name of 'Wars of the Three Kingdoms'). Tried for treason and found guilty, King Charles was executed, the monarchy was abolished, and England was proclaimed a republic with Cromwell at its head as Lord Protector.

Causes of the Conflict

The causes of the English Civil Wars were many and varied, changing as the war progressed. Indeed, such was the complexity of the conflict, it is often divided into three distinct phases:

- The First English Civil War (1642-1646)

- The Second English Civil War (Feb-Aug 1648)

- The Third English Civil War or Anglo-Scottish War (1650-1651)

The war was only the fighting phase of a struggle that went back to the very first year of Charles I's reign in 1625. King Charles' lack of compromise and unshakeable belief in his divine right to rule had brought him into direct and persistent conflict with an equally strong-willed Parliament that wanted a greater role in government. Parliament also wanted to prevent what it considered a steady return to Catholic practices in the Anglican Church masterminded by such Arminians as William Laud (1573-1645), the Archbishop of Canterbury. Many MPs were Puritans , and of these, the Independents or Congregationalists dominated. They wanted less power in the hands of bishops, more inclusion in the Church, and greater freedom for 'independent' congregations that assembled according to the individual believers' consciences and their own interpretation of the Bible .

The abolition of the monarchy was not the objective for the majority of MPs but rather a removal of what were considered the king's evil counsellors and a limit on his powers, particularly in terms of finance and raising taxes without Parliament's consent like the Ship Money to raise funds for warships. These grievances and others were presented by Parliament in the Petition of Right of 1628. The king, on the other hand, saw no need for Parliament and did not call one at all between 1629 and 1640, the period now called his 'Personal Rule', which began after his rejection of the Petition of Right.

Events came to a crisis point in 1639 when a Scottish army invaded northern England, the beginning of the Bishops' Wars (1639-40). These warriors were known as the Covenanters because they had signed a covenant swearing to defend the Scottish Presbyterian Church and its organisational head, the Kirk. Charles had made several unpopular moves to change religious practices in Scotland, including imposing a new Book of Common Prayer in 1637. In order to raise an army capable of defending his kingdom, Charles was obliged to recall Parliament. MPs seized this opportunity to forward their case to limit the king's powers. However, Charles dismissed what has become known as the Short Parliament after three weeks (April to May 1640). The Scots did not go away, though, and the king still needed money. Consequently, another Parliament was called in November 1640, and this was more successful, so much so, it became known as the Long Parliament. Then a second crisis arrived: a major rebellion in Ireland against English-Protestant rule, and so the king again needed funds for yet another army.

When MPs again presented their grievances concerning the king's rule, this time in the Grand Remonstrance of November 1641, Charles once more rejected them. The king, it seems, could not compromise, and he was still smarting at Parliament's trial and execution of his closest advisor Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Stafford (1593-1641) in May 1641. Stafford had been accused of preparing to bring an Irish army into England to aid the king, for which there was not much evidence, but it was a symptom of the atmosphere of distrust between the sovereign and many of his MPs. The king then shredded completely any remaining fragile threads of trust between the two sides when, in January 1642, he entered the sanctity of Parliament with a group of armed men and attempted to arrest the five MPs he considered most responsible for the Remonstrance. The five men, who included John Pym (1584-1643), a firebrand Puritan who was the king's most vocal opponent in Parliament, had been warned beforehand and were not there to be arrested. Still, even at this stage, not all MPs were against the king, and the division in Parliament over how to proceed with the crisis of government encouraged Charles to search for a military solution to what had hitherto been a conflict of only words. Both sides began to assemble their resources.

Battles & Sieges

By August 1642, Charles had established himself in Nottingham where a royal army was formed. The Royalists controlled the southwest and north of England with the port of Newcastle and the valuable coal of the region. Parliament controlled London, the Royal Navy, and southeast England. The two sides became known as the 'Cavaliers' (Royalists) and 'Roundheads' (Parliamentarians). The latter name derives from some Puritans wearing their hair very short, but this only pertained to the early period of the war, in reality, many officers on both sides wore long wigs and extravagant clothing.

The English Civil Wars involved over 600 battles and sieges, although many of these were small in scale. The first major engagement was at the Battle of Edgehill in Warwickshire in October 1642. Artillery, cavalry, pikemen, musketeers, and dragoons combined in a bloody engagement that took 1,500 lives. Prince Rupert, Count Palatine of the Rhine and Duke of Bavaria (1619-1682), the king's nephew, led the Royalist cavalry with aplomb but then wasted time and effort looting the enemy's baggage train. Parliament made better use of its reserve forces, and the battle ended, like so many more battles to come, in a draw. The king could then have marched on London but dithered at Banbury and Oxford, which gave Parliament time to regroup and raise the city 's militia force, the London Trained Bands. Charles then withdrew to Oxford which was made the Royalist capital.

Ten more major battles followed in the first half of 1643, and then, in July, Prince Rupert again came to the fore in the successful Storming of Bristol , a key port and armoury. The First Battle of Newbury in September 1643 saw 15,000 men fight on each side in the longest battle of the war, but it ended in another draw. Meanwhile, there were major sieges at Gloucester (Aug-Sep 1643), Hull (Sep 1643), and then York (Apr-Jul 1644).

The Parliamentarians had received a great boost in December 1643 when they signed an alliance with the Scottish Covenanters. The next significant engagement was the Battle of Marston Moor in July 1644, the largest battle of the war with over 45,000 men in the field. It ended in a great victory for the Parliamentarian forces. Marston Moor witnessed the skills of one rising new cavalry commander: Oliver Cromwell. The victory and the fall of York just after gave Parliament control of northern England with only a few isolated but, nevertheless, well-garrisoned castles still loyal to the king. Charles was at least boosted by the end of the rebellion in Ireland, which released some troops, but not a great many, for his cause.

Next came the Second Battle of Newbury in October 1644. The result was indecisive when a superior Roundhead army should have won victory. This missed opportunity led to bitter recriminations and the decision by Parliament to reorganise its forces into a more professionally trained and led army. The result was the New Model Army. Meanwhile, negotiations did take place between the two sides at Uxbridge in early 1645, but these came to nought. Parliament's long list of demands, the Uxbridge Propositions, was, unsurprisingly, rejected by the king. It may be that both sides were merely playing for time to regroup their armies after Newbury.

The Model Army's first major test came at the Battle of Naseby in Northamptonshire in June 1645. Led by Sir Thomas Fairfax (1612-1671) and with Cromwell once again showing his mastery of cavalry tactics, the New Model Army won a crushing victory that destroyed the king's infantry. The king fled to Wales and then to the far north of England. At the Siege of Bristol in 1645 , the Royalists lost their main port. With a few more battles, culminating in victory at the Battle of Stow-on-the-Wold in March 1646, so ended the First English Civil War. However, the capture of Charles' personal writing cabinet at Naseby revealed the monarch had no intention of ever negotiating for peace and was even trying to engage Catholic troops from Ireland to fight on for his cause.

The Second Civil War

The words of Edward Montagu, Earl of Manchester (l. 1602-1671), now seemed to ring truer than ever: "If we fight a hundred times and beat him ninety-nine times, he will be the King still" (Hunt, 149-150). Charles was not going to give up and so the Second Civil War began. The summer of 1648 saw the Siege of Pembroke, the Battle of Maidstone, and the Siege of Colchester, but by August, the king's fortunes would plummet to new depths. The king had fled to the north of England, but he was handed over to the Parliamentarians in January 1647. He then escaped his confinement and established himself on the Isle of Wight to continue to direct the war from there. The Scots then became his allies as the Covenanters now considered the Puritan Parliament a greater threat to Presbyterianism than Charles. In December 1647, the king had signed the treaty known as the Engagement where he promised to promote the Presbyterian Church in England. The king hoped the Scots would invade the north of England and that rebellions would arise in southeast England and Wales. This determination to continue the war lost him more supporters. The king was seen as a warmonger who would not accept defeat.

The planned Royalist uprisings were easily crushed or prevented altogether. At the Battle of Preston in August 1648, the New Model Army, led by Oliver Cromwell, won a great victory against the Anglo-Scottish Royalists. After Preston, Cromwell recaptured Berwick and Carlisle, and he took Pontefract, bringing this brief second war to a close. The king was brought to London from the Isle of Wight, put on trial in January 1649, and, found guilty of treason, he was executed on 30 January. The institutions of the monarchy and the House of Lords were abolished, and England became a republic. For these reasons, the events of 1649 are often called the 'English Revolution', although some historians disagree since the middle and lower institutions of government remained much the same. Crucially, though, the monarchy was not abolished in Scotland, where the late King Charles' eldest son became Charles II of Scotland. The civil war was not quite over yet.

Third Civil War

As the third war got started, Parliament had its hands full dealing with a major rebellion by pro-Royalist forces in Ireland. In the late summer of 1649, Cromwell led 12,000 men of the New Model Army and crushed the rebels with utter ruthlessness. The next main engagement of this third phase of the civil war was the Battle of Dunbar in September 1650.

After Ireland, Cromwell returned to lead the New Model Army into Scotland, where Dunbar, just across the border, became his supply base. Cromwell tried several times to attack Edinburgh but was not successful, and then, while retreating to Dunbar, the Scottish pursued the invaders. Cromwell could very easily have been trapped, and his army faced disaster, but the poor positioning of Scottish troops meant he could, once again, use his superior heavy cavalry to winning effect. Around 3,000 Scots were killed and perhaps 6,000 taken prisoner after the battle. Edinburgh was then captured on Christmas Eve of 1650. The remaining Scottish army was defeated at the Battle of Worcester in September 1651. So ended the English Civil Wars. Charles II fled to France. In England, Oliver Cromwell eventually became Lord Protector, head of the military state known as the 'Commonwealth' Republic that lasted until 1660 and the Restoration of the Monarchy that saw Charles finally crowned King of England.

Impact of the Wars

The impact of the English Civil Wars was enormous and long-lasting. Around one in four males in England and Wales were actively involved in the fighting. Non-combatants had to endure high taxes, confiscation of their land and property, destruction of their crops, forced labour to build defences, and deadly diseases brought by soldiers. One in ten people in urban areas lost their homes. Around 100,000 soldiers died during the conflict and another 100,000 civilians. Taken as a proportion of the then population, these deaths were greater than those sustained in the First World War (1914-1918).

Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

The political ramifications of Charles I's execution and the abolition of both the monarchy and the House of Lords may seem short-lived when considering the Restoration occurred just nine years after the last battle. However, the political landscape was changed forever since the political struggles leading up to the war had greatly increased the powers of Parliament, and these remained thereafter. Cromwell's Acts of Parliament while Lord Protector were reversed, but King Charles II was now a monarch whose rule must be shared with the House of Commons and the House of Lords.

The Civil Wars were also a religious struggle. The Anglican Church was reformed, with bishops, clerical courts, and the Book of Common Prayer all swept away. The boom in printed literature provoked people's minds into considering just what should be the obligations and responsibilities of those who governed them both in politics and in religious life. A great number of religious groups were born, some of which gave women equal rights of participation, as "the war split the country by conscience uninformed by class" (Morrill, 370). There was an atmosphere of freedom of thought like never before as state and Church censorship became impossible to apply, such was the quantity of new works being printed by men and women. The Lord Protector did steadily impose more radical Puritan practices in churches, but misguided policies like prohibiting the celebration of Christmas did nothing for Cromwell's popularity. Many were happy to see the monarchy return in 1660 as they hoped for a return to the old days of peace and stability before this terrible conflict had ripped the three kingdoms apart.

Subscribe to topic Related Content Books Cite This Work License

Bibliography

- Anderson, Angela & Scarboro, Dale. Stuart Britain. Hodder Education, 2015.

- Asquith, Stuart & Warner, Chris. New Model Army 1645-60 . Osprey Publishing, 1981.

- Barratt, John. Sieges of the English Civil Wars. Pen & Sword Military, 2009.

- Bennett, Martyn. The English Civil War 1640-1649 . Routledge, 2014.

- Evans, Martin Marix & Turner, Graham. Naseby 1645. Osprey Publishing, 2007.

- Gaunt, Peter. The English Civil Wars. Osprey Publishing, 2003.

- Hunt, Tristram. The English Civil War at First Hand. Penguin UK, 2011.

- Miller, John. Early Modern Britain, 1450–1750 . Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- Morrill, John. The Oxford Illustrated History of Tudor & Stuart Britain. Oxford University Press, 1996.

- Reid, Stuart & Turner, Graham. Dunbar 1650. Osprey Publishing, 2004.

- Wanklyn, Malcolm. Decisive Battles of the English Civil War. Pen and Sword Military, 2014.

About the Author

Translations

We want people all over the world to learn about history. Help us and translate this definition into another language!

Questions & Answers

What was the main cause of the english civil war, who won the english civil war, what happened in the english civil war, what does the term 'english civil war' mean, what were the effects of the english civil war, related content.

Oliver Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell

Charles I of England

Charles II of England

Battle of Dunbar in 1650

Consequences of the English Civil Wars

Free for the world, supported by you.

World History Encyclopedia is a non-profit organization. For only $5 per month you can become a member and support our mission to engage people with cultural heritage and to improve history education worldwide.

Recommended Books

Cite This Work

Cartwright, M. (2022, February 18). English Civil Wars . World History Encyclopedia . Retrieved from https://www.worldhistory.org/English_Civil_Wars/

Chicago Style

Cartwright, Mark. " English Civil Wars ." World History Encyclopedia . Last modified February 18, 2022. https://www.worldhistory.org/English_Civil_Wars/.

Cartwright, Mark. " English Civil Wars ." World History Encyclopedia . World History Encyclopedia, 18 Feb 2022. Web. 06 Sep 2024.

License & Copyright

Submitted by Mark Cartwright , published on 18 February 2022. The copyright holder has published this content under the following license: Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike . This license lets others remix, tweak, and build upon this content non-commercially, as long as they credit the author and license their new creations under the identical terms. When republishing on the web a hyperlink back to the original content source URL must be included. Please note that content linked from this page may have different licensing terms.

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Why Publish with EHR?

- About The English Historical Review

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Books for Review

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

The English Civil War: Conflict and Contexts, 1640–49, ed. John Adamson

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Geoffrey Smith, The English Civil War: Conflict and Contexts, 1640–49, ed. John Adamson, The English Historical Review , Volume CXXVI, Issue 520, June 2011, Pages 694–695, https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/cer086

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The title could mislead some people, for this book goes far beyond being just another collection of essays on the English Civil War, or whatever these days we choose to call the series of convulsions that distracted the three Stuart kingdoms for twenty years. For this is a challenging and important book that makes a number of valuable contributions to our understanding of that complex but perennially favourite subject. Both John Adamson's introduction and the different essays support the editor's claim for ‘the subject's vitality and enduring power to fascinate’.

The introduction is particularly valuable, as it presents a lucid and incisive survey of the whole complex historiography of the Civil War. Beginning with a consideration of the extraordinarily impressive achievement of S.R. Gardiner, working at the high tide of Gladstonian and Victorian Liberalism, Adamson traces the once dominant interpretations and influences of Gardiner, Weber, Marx, Tawney, Hill and others, continuing his survey down to the current fluid state of a wide-ranging and sometimes controversial reconfiguring of issues and debates by a new generation of historians. For long periods, certain favoured groups—the godly but also bourgeois capitalist Puritans, the gentry (whether rising or falling), the ‘county communities’, the House of Commons, the radical Levellers and Diggers—basked in the spotlight of historical interest, while other key players in the conflict, notably the royal court, the nobility and the royalists, languished in outer darkness, in what the editor calls ‘a scholarly No Man's Land’. Viewed as standing in opposition to the progressive march of history, they may have enjoyed some colourful or romantic appeal, but they were essentially inconsequential, not deserving of the attention of serious historians.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Short-term Access

To purchase short-term access, please sign in to your personal account above.

Don't already have a personal account? Register

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| November 2016 | 2 |

| December 2016 | 3 |

| January 2017 | 8 |

| February 2017 | 7 |

| March 2017 | 7 |

| April 2017 | 6 |

| May 2017 | 6 |

| July 2017 | 1 |

| August 2017 | 3 |

| October 2017 | 10 |

| November 2017 | 16 |

| January 2018 | 2 |

| February 2018 | 4 |

| March 2018 | 11 |

| April 2018 | 2 |

| May 2018 | 3 |

| June 2018 | 1 |

| July 2018 | 4 |

| August 2018 | 1 |

| September 2018 | 3 |

| October 2018 | 7 |

| November 2018 | 12 |

| December 2018 | 3 |

| January 2019 | 2 |

| February 2019 | 6 |

| March 2019 | 7 |

| April 2019 | 3 |

| August 2019 | 1 |

| October 2019 | 1 |

| November 2019 | 2 |

| December 2019 | 2 |

| January 2020 | 2 |

| February 2020 | 2 |

| May 2020 | 4 |

| September 2020 | 3 |

| October 2020 | 2 |

| November 2020 | 1 |

| December 2020 | 1 |

| February 2021 | 8 |

| March 2021 | 1 |

| May 2021 | 1 |

| October 2021 | 1 |

| November 2021 | 3 |

| January 2022 | 2 |

| March 2022 | 1 |

| May 2022 | 1 |

| July 2022 | 1 |

| October 2022 | 8 |

| November 2022 | 3 |

| December 2022 | 3 |

| March 2023 | 4 |

| June 2023 | 1 |

| August 2023 | 1 |

| October 2023 | 2 |

| November 2023 | 5 |

| December 2023 | 2 |

| February 2024 | 1 |

| April 2024 | 1 |

| May 2024 | 3 |

| June 2024 | 4 |

| August 2024 | 1 |

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1477-4534

- Print ISSN 0013-8266

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Religion in the British Civil Wars

Introduction, general overviews.

- Primary Sources

- Scotland and Ireland

- Radical Religion

- Atlantic Colonies

- Liberty of Conscience

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- African American Religions

- Catholicism

- Evangelicalism and Conversion

- Gender in the Atlantic World

- Ireland and the Atlantic World

- Protestantism

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Ecology and Nineteenth-Century Anglophone Atlantic Literature

- Maritime Literature

- The History of Mary Prince (1831)

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Religion in the British Civil Wars by Rachel N. Schnepper LAST REVIEWED: 26 February 2013 LAST MODIFIED: 26 February 2013 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199730414-0186

Religion and the British Civil Wars, also known as the War of the Three Kingdoms or the English Revolution, are inextricably interconnected: it is impossible to understand the causes and course of the English Revolution and exclude religion. Once the Long Parliament committed itself to the reformation of the Church of England, the question remained of what shape this reform should take. Competing visions of church-government or ecclesiologies, such as Presbyterianism, Congregationalism, and Erastianism, dominated debate within the halls of Parliament. However, the breakdown of state-controlled religious conformity released an explosion of new and often radical sects. These radical denominations, which included Ranters, Baptists, Diggers, Levellers, and Quakers, played a prominent role in both political and religious considerations of the Revolution. Furthermore, debates on national religious settlement favoring one church government over another were also complicated by the appearance of an initially minor, but sustained and increasingly important, transatlantic conversation over liberty of conscience. The centrality of religion was recognized, to a degree, in the 19th century, with Samuel Rawson Gardiner terming the English Revolution as the Puritan Revolution. Until comparatively recently, however, the religious factors in the Revolution tended to be downplayed or explained away in nonreligious terms. Recent historiography has renewed interest in the religious dimensions of the English Revolution, an interest that has been shaped by a reconceptualization and redefinition of the meanings of religious belief for ordinary men and women in the 17th century. It is now almost universally agreed upon by historians of the English Revolution that the civil wars between the three kingdoms of the British monarchy—England, Scotland, and Ireland—erupted principally over differing visions of national church-government. Despite being a relatively recent intervention in the scholarship, the literature on religion in the English Revolution is vast, and it continues to provide fertile ground for research and debate. With such breadth of scholarship, the focus of this bibliography must necessarily be truncated and selective. Nevertheless, many of the works included in this article are intended to give the researcher an overview not only of religious history in England in the 1640s and 1650s, but also of the other components of the British monarchy, including not just Scotland and Ireland but also the Atlantic colonies of the nascent British Empire.

The almost annual appearance of general overviews of the English Revolution or the British Civil Wars points to the continued vitality of this historiographical field. Researchers new to the field will probably gain the most by starting with Woolrych 2002 , which addresses the “multiple kingdoms” with multiple religions problem of the British state, integrating the Scottish and Irish histories into what until recently was mostly focused on England. This recent shift to focusing on the problem of multiple kingdoms with multiple religions within the British state owes its origins to Russell 1990 , but Gardiner 2011 , a multivolume series on the outbreak and course of the Revolution, engages with similar ideas and themes. Recent broad narrative accounts of 1640–1660, such as Scott 2000 , push this trend in the scholarship even further, locating the British Isles’ century of revolution within a pan-European context. Morrill 1993 builds upon the historiographical intervention of Russell 1990 but places more emphasis on the centrality of religious belief in the outbreak and course of the English Revolution. Morrill 1993 continues to be relevant, as evidenced by Prior and Burgess 2011 , which takes the author’s claim that the British Civil Wars were “the last of the Wars of Religion” (p. 68) as its point of departure. Just when exactly the Revolution radicalized continues to be a fiercely debated topic, but Cressy 2006 , looking at the first two years of the Revolution from a wider, more popular point of view, challenges prevailing notions that the Revolution radicalized in the mid- to late 1640s, locating the seeds of popular radicalism from its outset. Adamson 2007 looks at the same period as Cressy 2006 but from a wholly different perspective, at the godly elites in the House of Lords.

Adamson, John. The Noble Revolt: The Overthrow of Charles I . London: Orion, 2007.

Exhaustive reconstruction of events from 1640 to 1642 that focuses exclusively on the peers who, Adamson argues, were responsible for the revolt against Charles I. In his provocative analysis of these peers, Adamson maintains that their religious and political frustrations at the policies of the monarchy incited them to revolt.

Cressy, David. England on Edge: Crisis and Revolution, 1640–1642 . Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Cressy argues that England was in the midst of revolutionary turmoil and upheaval before the outbreak of civil war in 1642. The bulk of the book, Part 2, focuses exclusively on English religious culture prior to 1642, tracing the rise and collapse of Laudianism and the factionalism that emerged in its wake.

Gardiner, Samuel Rawson. History of England from the Accession of James I to the Outbreak of the Civil War, 1603–1642 . 10 vols. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2011.

First published in 1883–1884; continued in History of the Great Civil War, 1642–1649 (5 vols., London: Longmans, Green, 1893) and History of the Commonwealth and Protectorate, 1649–1660 (4 vols., London: Longmans, Green, 1903). Exhaustive treatment of constitutional, religious, and legal thought from the early Stuart period and Revolution. Useful mostly for scholars interested in historiographical evolution.

Morrill, John. The Nature of the English Revolution: Essays . New York: Longman, 1993.

A collection of essays by Morrill subdivided into three thematic sections: the importance of localism during the Civil Wars, the centrality of religion to the conflict, and a push to see the English Revolution from a British point of view. His essay titled “The Religious Context of the English Civil War” famously claimed that the English Civil War was “the last of Europe’s wars of religion” (pp. 45–68).

Prior, Charles W. A., and Glenn Burgess, eds. England’s Wars of Religion, Revisited . Brookfield, VT: Ashgate, 2011.

Introduction argues that, until recently, historians understood the English Revolution as a struggle to preserve civil liberty, but one in which participants used a religious idiom to express a politically revolutionary ideology. Each essay rejects this view, maintaining that historians must take seriously the religious language of the time.

Russell, Conrad. The Causes of the English Civil War . Oxford: Clarendon, 1990.

Russell’s seminal breakdown of the causes of the English Civil Wars, attributing them to the constitutional problem of multiple kingdoms, the religious problem of competing theologies, and the financial and personal poverty of Charles I.

Scott, Jonathan. England’s Troubles: Seventeenth-Century English Political Instability in European Context . Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

DOI: 10.1017/CBO9780511605741

Scott situates England’s century of “troubles” within the wider contexts of European confessionalization, state formation, and militarization of the 17th century.

Woolrych, Austin. Britain in Revolution: 1625–1660 . New York: Oxford University Press, 2002.

Massive narrative account of the English Revolution with particular focus on Irish and Scottish roles.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Atlantic History »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Abolition of Slavery

- Abolitionism and Africa

- Africa and the Atlantic World

- African Religion and Culture

- African Retailers and Small Artisans in the Atlantic World

- Age of Atlantic Revolutions, The

- Alexander von Humboldt and Transatlantic Studies

- America, Pre-Contact

- American Revolution, The

- Anti-Catholicism and Anti-Popery

- Army, British

- Art and Artists

- Asia and the Americas and the Iberian Empires

- Atlantic Biographies

- Atlantic Creoles

- Atlantic History and Hemispheric History

- Atlantic Migration

- Atlantic New Orleans: 18th and 19th Centuries

- Atlantic Trade and the British Economy

- Atlantic Trade and the European Economy

- Bacon's Rebellion

- Barbados in the Atlantic World

- Barbary States

- Berbice in the Atlantic World

- Black Atlantic in the Age of Revolutions, The

- Bolívar, Simón

- Borderlands

- Bourbon Reforms in the Spanish Atlantic, The

- Brazil and Africa

- Brazilian Independence

- Britain and Empire, 1685-1730

- British Atlantic Architectures

- British Atlantic World

- Buenos Aires in the Atlantic World

- Cabato, Giovanni (John Cabot)

- Cannibalism

- Captain John Smith

- Captivity in Africa

- Captivity in North America

- Caribbean, The

- Cartier, Jacques

- Cattle in the Atlantic World

- Central American Independence

- Central Europe and the Atlantic World

- Chartered Companies, British and Dutch

- Chinese Indentured Servitude in the Atlantic World

- Church and Slavery

- Cities and Urbanization in Portuguese America

- Citizenship in the Atlantic World

- Class and Social Structure

- Coastal/Coastwide Trade

- Cod in the Atlantic World

- Colonial Governance in Spanish America

- Colonial Governance in the Atlantic World

- Colonialism and Postcolonialism

- Colonization, Ideologies of

- Colonization of English America

- Communications in the Atlantic World

- Comparative Indigenous History of the Americas

- Confraternities

- Constitutions

- Continental America

- Cook, Captain James

- Cortes of Cádiz

- Cosmopolitanism

- Credit and Debt

- Creek Indians in the Atlantic World, The

- Creolization

- Criminal Transportation in the Atlantic World

- Crowds in the Atlantic World

- Death in the Atlantic World

- Demography of the Atlantic World

- Diaspora, Jewish

- Diaspora, The Acadian

- Disease in the Atlantic World

- Domestic Production and Consumption in the Atlantic World

- Domestic Slave Trades in the Americas

- Dreams and Dreaming

- Dutch Atlantic World

- Dutch Brazil

- Dutch Caribbean and Guianas, The

- Early Modern Amazonia

- Early Modern France

- Economy and Consumption in the Atlantic World

- Economy of British America, The

- Edwards, Jonathan

- Emancipation

- Empire and State Formation

- Enlightenment, The

- Environment and the Natural World

- Europe and Africa

- Europe and the Atlantic World, Northern

- Europe and the Atlantic World, Western

- European Enslavement of Indigenous People in the Americas

- European, Javanese and African and Indentured Servitude in...

- Female Slave Owners

- First Contact and Early Colonization of Brazil

- Fiscal-Military State

- Forts, Fortresses, and Fortifications

- Founding Myths of the Americas

- France and Empire

- France and its Empire in the Indian Ocean

- France and the British Isles from 1640 to 1789

- Free People of Color

- Free Ports in the Atlantic World

- French Army and the Atlantic World, The

- French Atlantic World

- French Emancipation

- French Revolution, The

- Gender in Iberian America

- Gender in North America

- Gender in the Caribbean

- George Montagu Dunk, Second Earl of Halifax

- Georgia in the Atlantic World

- German Influences in America

- Germans in the Atlantic World

- Giovanni da Verrazzano, Explorer

- Glorious Revolution

- Godparents and Godparenting

- Great Awakening

- Green Atlantic: the Irish in the Atlantic World

- Guianas, The

- Haitian Revolution, The

- Hanoverian Britain

- Havana in the Atlantic World

- Hinterlands of the Atlantic World

- Histories and Historiographies of the Atlantic World

- Hunger and Food Shortages

- Iberian Atlantic World, 1600-1800

- Iberian Empires, 1600-1800

- Iberian Inquisitions

- Idea of Atlantic History, The

- Impact of the French Revolution on the Caribbean, The

- Indentured Servitude

- Indentured Servitude in the Atlantic World, Indian

- India, The Atlantic Ocean and

- Indigenous Knowledge

- Indigo in the Atlantic World

- Internal Slave Migrations in the Americas

- Interracial Marriage in the Atlantic World

- Iroquois (Haudenosaunee)

- Islam and the Atlantic World

- Itinerant Traders, Peddlers, and Hawkers

- Jamaica in the Atlantic World

- Jefferson, Thomas

- Jews and Blacks

- Labor Systems

- Land and Propert in the Atlantic World

- Language, State, and Empire

- Languages, Caribbean Creole

- Latin American Independence

- Law and Slavery

- Legal Culture

- Leisure in the British Atlantic World

- Letters and Letter Writing

- Literature and Culture

- Literature of the British Caribbean

- Literature, Slavery and Colonization

- Liverpool in The Atlantic World 1500-1833

- Louverture, Toussaint

- Manumission

- Maps in the Atlantic World

- Maritime Atlantic in the Age of Revolutions, The

- Markets in the Atlantic World

- Maroons and Marronage

- Marriage and Family in the Atlantic World

- Material Culture in the Atlantic World

- Material Culture of Slavery in the British Atlantic

- Medicine in the Atlantic World

- Mental Disorder in the Atlantic World

- Mercantilism

- Merchants in the Atlantic World

- Merchants' Networks

- Migrations and Diasporas

- Minas Gerais

- Mining, Gold, and Silver

- Missionaries

- Missionaries, Native American

- Money and Banking in the Atlantic Economy

- Monroe, James

- Morris, Gouverneur

- Music and Music Making

- Napoléon Bonaparte and the Atlantic World

- Nation and Empire in Northern Atlantic History

- Nation, Nationhood, and Nationalism

- Native American Histories in North America

- Native American Networks

- Native American Religions

- Native Americans and Africans

- Native Americans and the American Revolution

- Native Americans and the Atlantic World

- Native Americans in Cities

- Native Americans in Europe

- Native North American Women

- Native Peoples of Brazil

- Natural History

- Networks for Migrations and Mobility

- Networks of Science and Scientists

- New England in the Atlantic World

- New France and Louisiana

- New York City

- Nineteenth-Century Atlantic World

- Nineteenth-Century France

- Nobility and Gentry in the Early Modern Atlantic World

- North Africa and the Atlantic World

- Northern New Spain

- Novel in the Age of Revolution, The

- Oceanic History

- Pacific, The

- Paine, Thomas

- Papacy and the Atlantic World

- People of African Descent in Early Modern Europe

- Pets and Domesticated Animals in the Atlantic World

- Philadelphia

- Philanthropy

- Phillis Wheatley

- Plantations in the Atlantic World

- Poetry in the British Atlantic

- Political Participation in the Nineteenth Century Atlantic...

- Polygamy and Bigamy

- Port Cities, British

- Port Cities, British American

- Port Cities, French

- Port Cities, French American

- Port Cities, Iberian

- Ports, African

- Portugal and Brazile in the Age of Revolutions

- Portugal, Early Modern

- Portuguese Atlantic World

- Poverty in the Early Modern English Atlantic

- Pre-Columbian Transatlantic Voyages

- Pregnancy and Reproduction

- Print Culture in the British Atlantic

- Proprietary Colonies

- Quebec and the Atlantic World, 1760–1867

- Race and Racism

- Race, The Idea of

- Reconstruction, Democracy, and United States Imperialism

- Red Atlantic

- Refugees, Saint-Domingue

- Religion and Colonization

- Religion in the British Civil Wars

- Religious Border-Crossing

- Religious Networks

- Representations of Slavery

- Republicanism

- Rice in the Atlantic World

- Rio de Janeiro

- Russia and North America

- Saint Domingue

- Saint-Louis, Senegal

- Salvador da Bahia

- Scandinavian Chartered Companies

- Science and Technology (in Literature of the Atlantic Worl...

- Science, History of

- Scotland and the Atlantic World

- Sea Creatures in the Atlantic World

- Second-Hand Trade

- Settlement and Region in British America, 1607-1763

- Seven Years' War, The

- Sex and Sexuality in the Atlantic World

- Shakespeare and the Atlantic World

- Ships and Shipping

- Slave Codes

- Slave Names and Naming in the Anglophone Atlantic

- Slave Owners In The British Atlantic

- Slave Rebellions

- Slave Resistance in the Atlantic World

- Slave Trade and Natural Science, The

- Slave Trade, The Atlantic

- Slavery and Empire

- Slavery and Fear

- Slavery and Gender

- Slavery and the Family

- Slavery, Atlantic

- Slavery, Health, and Medicine

- Slavery in Africa

- Slavery in Brazil

- Slavery in British America

- Slavery in British and American Literature

- Slavery in Danish America

- Slavery in Dutch America and the West Indies

- Slavery in New England

- Slavery in North America, The Growth and Decline of

- Slavery in the Cape Colony, South Africa

- Slavery in the French Atlantic World

- Slavery, Native American

- Slavery, Public Memory and Heritage of

- Slavery, The Origins of

- Slavery, Urban

- Sociability in the British Atlantic

- Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts...

- South Atlantic

- South Atlantic Creole Archipelagos

- South Carolina

- Sovereignty and the Law

- Spain, Early Modern

- Spanish America After Independence, 1825-1900

- Spanish American Port Cities

- Spanish Atlantic World

- Spanish Colonization to 1650

- Subjecthood in the Atlantic World

- Sugar in the Atlantic World

- Swedish Atlantic World, The

- Technology, Inventing, and Patenting

- Textiles in the Atlantic World

- Texts, Printing, and the Book

- The American West

- The Danish Atlantic World

- The French Lesser Antilles

- The Fur Trade

- The Spanish Caribbean

- Time(scapes) in the Atlantic World

- Toleration in the Atlantic World

- Transatlantic Political Economy

- Travel Writing (in the Atlantic World)

- Tudor and Stuart Britain in the Wider World, 1485-1685

- Universities

- USA and Empire in the 19th Century

- Venezuela and the Atlantic World

- Visual Art and Representation

- War and Trade

- War of 1812

- War of the Spanish Succession

- Warfare in Spanish America

- Warfare in 17th-Century North America

- Warfare, Medicine, and Disease in the Atlantic World

- West Indian Economic Decline

- Whitefield, George

- Whiteness in the Atlantic World

- William Blackstone

- William Shakespeare, The Tempest (1611)

- William Wilberforce

- Witchcraft in the Atlantic World

- Women and the Law

- Women Prophets

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [185.194.105.172]

- 185.194.105.172

3 January 2024

Stephen croad prize 2023.

| Receiving the Stephen Croad Essay Prize from Giles Quarme FRIBA. |

| Speaking about my essay on Balthazar Gerbier and Hamstead Marshall. |

21 July 2023

Guest blog: princess elizabeth stuart (1635-50) (mary mcvicker, writer).

| (1637) by Van Dyck (Princess Elizabeth Stuart second-right). |

Colchester Siege Spectacular (19-20 August, Castle Park, Colchester)

My article and interactive map on the Siege of Colchester (1648) still get a lot of traffic - it appears there's still great interest in the siege, so it's great to see that the city's holding a weekend-long event over August Bank Holiday - see video preview above.

8 February 2022

Website changes: englishcivilwar.org.

A quick update on some changes I've had to make to englishcivilwar.org:

Due to the weight of other commitments, I've been unable to update the Events section as regularly as I'd like, so I've now closed this page - I will however continue to post events on the englishcivilwar.org Facebook page , so if you do have events you want to promote, please send them on and I'll try to post/repost as time allows. For the same reason I've also closed the Forum (again, the quickest way to get answers via a knowledgable community of 17th century buffs is via the Facebook page ).

Thanks to everyone who has contributed ECW/17th century-related events and queries via these two sections over the past decade.

Home — Essay Samples — History — History of the United States — Civil War

Essays on Civil War

Civil war essay topic examples.

The American Civil War is a significant part of our nation's past, filled with fascinating stories, debates, and events. Whether you want to argue, compare, describe, persuade, or narrate, we have a wide range of essay topics that will take you on a journey through this pivotal period in American history. Join us as we delve into the heart of the conflict, examine key figures, analyze strategies, vividly depict battles, and explore the moral imperatives that shaped the course of the Civil War. These essay topics will guide you on your historical voyage, offering insights into the complexities and enduring legacies of this era.

Argumentative Essays