Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

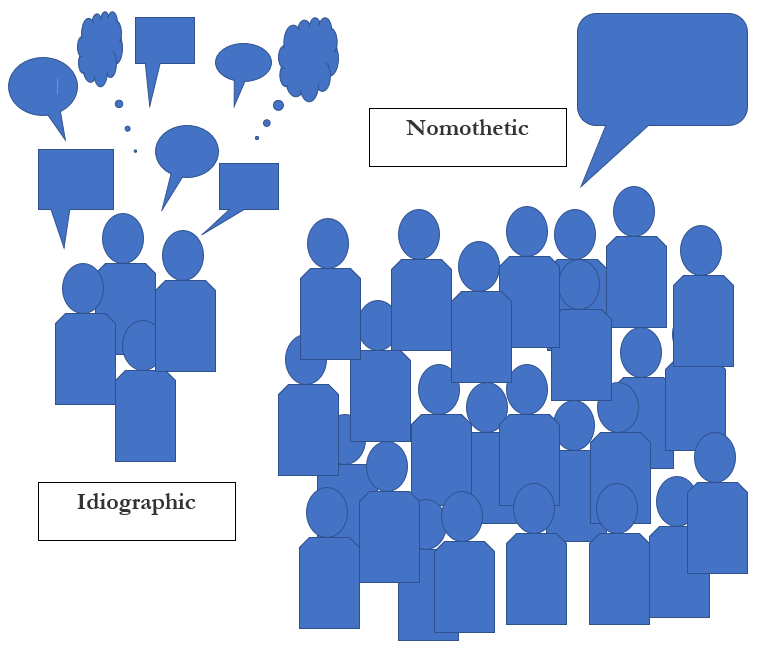

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

| Approach | What does it involve? |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | Researchers collect rich data on a topic of interest and develop theories . |

| Researchers immerse themselves in groups or organizations to understand their cultures. | |

| Action research | Researchers and participants collaboratively link theory to practice to drive social change. |

| Phenomenological research | Researchers investigate a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting participants’ lived experiences. |

| Narrative research | Researchers examine how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences. |

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

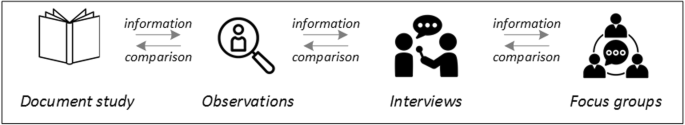

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

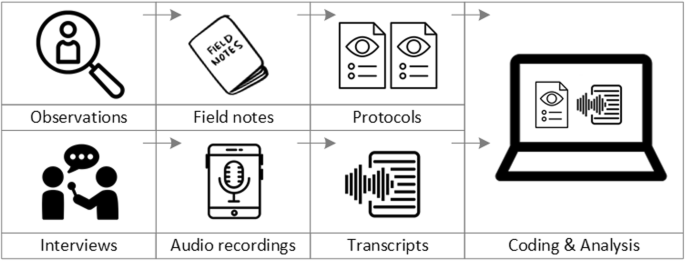

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

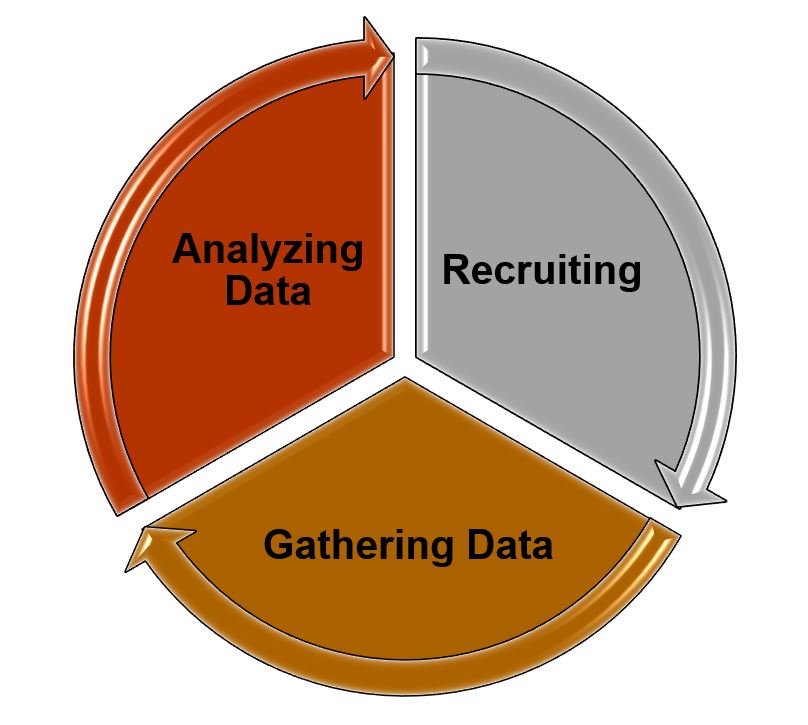

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

| Approach | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| To describe and categorize common words, phrases, and ideas in qualitative data. | A market researcher could perform content analysis to find out what kind of language is used in descriptions of therapeutic apps. | |

| To identify and interpret patterns and themes in qualitative data. | A psychologist could apply thematic analysis to travel blogs to explore how tourism shapes self-identity. | |

| To examine the content, structure, and design of texts. | A media researcher could use textual analysis to understand how news coverage of celebrities has changed in the past decade. | |

| To study communication and how language is used to achieve effects in specific contexts. | A political scientist could use discourse analysis to study how politicians generate trust in election campaigns. |

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Qualitative Research : Definition

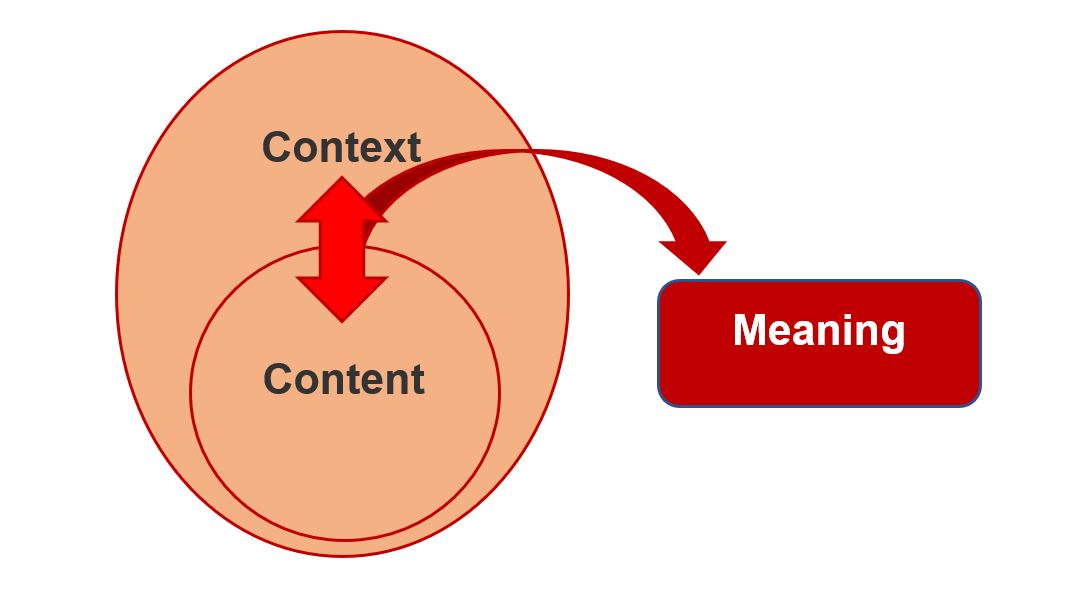

Qualitative research is the naturalistic study of social meanings and processes, using interviews, observations, and the analysis of texts and images. In contrast to quantitative researchers, whose statistical methods enable broad generalizations about populations (for example, comparisons of the percentages of U.S. demographic groups who vote in particular ways), qualitative researchers use in-depth studies of the social world to analyze how and why groups think and act in particular ways (for instance, case studies of the experiences that shape political views).

Events and Workshops

- Introduction to NVivo Have you just collected your data and wondered what to do next? Come join us for an introductory session on utilizing NVivo to support your analytical process. This session will only cover features of the software and how to import your records. Please feel free to attend any of the following sessions below: April 25th, 2024 12:30 pm - 1:45 pm Green Library - SVA Conference Room 125 May 9th, 2024 12:30 pm - 1:45 pm Green Library - SVA Conference Room 125

- Next: Choose an approach >>

- Choose an approach

- Find studies

- Learn methods

- Getting Started

- Get software

- Get data for secondary analysis

- Network with researchers

- Last Updated: Aug 9, 2024 2:09 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.stanford.edu/qualitative_research

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research (2nd edn)

Patricia Leavy Independent Scholar Kennebunk, ME, USA

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research, second edition, presents a comprehensive retrospective and prospective review of the field of qualitative research. Original, accessible chapters written by interdisciplinary leaders in the field make this a critical reference work. Filled with robust examples from real-world research; ample discussion of the historical, theoretical, and methodological foundations of the field; and coverage of key issues including data collection, interpretation, representation, assessment, and teaching, this handbook aims to be a valuable text for students, professors, and researchers. This newly revised and expanded edition features up-to-date examples and topics, including seven new chapters on duoethnography, team research, writing ethnographically, creative approaches to writing, writing for performance, writing for the public, and teaching qualitative research.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 6 |

| October 2022 | 10 |

| October 2022 | 53 |

| October 2022 | 93 |

| October 2022 | 31 |

| October 2022 | 30 |

| October 2022 | 216 |

| October 2022 | 100 |

| October 2022 | 100 |

| October 2022 | 39 |

| October 2022 | 74 |

| October 2022 | 27 |

| October 2022 | 41 |

| October 2022 | 18 |

| October 2022 | 20 |

| October 2022 | 23 |

| October 2022 | 99 |

| October 2022 | 146 |

| October 2022 | 22 |

| October 2022 | 38 |

| October 2022 | 5 |

| October 2022 | 28 |

| October 2022 | 94 |

| October 2022 | 217 |

| October 2022 | 37 |

| October 2022 | 33 |

| October 2022 | 7 |

| October 2022 | 48 |

| October 2022 | 68 |

| October 2022 | 11 |

| October 2022 | 49 |

| October 2022 | 71 |

| October 2022 | 36 |

| October 2022 | 65 |

| October 2022 | 131 |

| October 2022 | 115 |

| October 2022 | 102 |

| October 2022 | 97 |

| October 2022 | 33 |

| October 2022 | 19 |

| October 2022 | 27 |

| October 2022 | 11 |

| October 2022 | 28 |

| October 2022 | 32 |

| October 2022 | 88 |

| October 2022 | 57 |

| October 2022 | 115 |

| November 2022 | 110 |

| November 2022 | 71 |

| November 2022 | 42 |

| November 2022 | 97 |

| November 2022 | 22 |

| November 2022 | 102 |

| November 2022 | 87 |

| November 2022 | 89 |

| November 2022 | 229 |

| November 2022 | 34 |

| November 2022 | 56 |

| November 2022 | 9 |

| November 2022 | 28 |

| November 2022 | 53 |

| November 2022 | 107 |

| November 2022 | 306 |

| November 2022 | 19 |

| November 2022 | 137 |

| November 2022 | 93 |

| November 2022 | 30 |

| November 2022 | 20 |

| November 2022 | 117 |

| November 2022 | 22 |

| November 2022 | 16 |

| November 2022 | 31 |

| November 2022 | 36 |

| November 2022 | 42 |

| November 2022 | 49 |

| November 2022 | 77 |

| November 2022 | 15 |

| November 2022 | 29 |

| November 2022 | 14 |

| November 2022 | 13 |

| November 2022 | 1 |

| November 2022 | 25 |

| November 2022 | 65 |

| November 2022 | 34 |

| November 2022 | 39 |

| November 2022 | 26 |

| November 2022 | 53 |

| November 2022 | 61 |

| November 2022 | 8 |

| November 2022 | 51 |

| November 2022 | 24 |

| November 2022 | 89 |

| November 2022 | 35 |

| November 2022 | 12 |

| December 2022 | 90 |

| December 2022 | 53 |

| December 2022 | 68 |

| December 2022 | 44 |

| December 2022 | 20 |

| December 2022 | 86 |

| December 2022 | 63 |

| December 2022 | 55 |

| December 2022 | 41 |

| December 2022 | 102 |

| December 2022 | 47 |

| December 2022 | 27 |

| December 2022 | 29 |

| December 2022 | 27 |

| December 2022 | 32 |

| December 2022 | 95 |

| December 2022 | 83 |

| December 2022 | 60 |

| December 2022 | 72 |

| December 2022 | 28 |

| December 2022 | 102 |

| December 2022 | 40 |

| December 2022 | 154 |

| December 2022 | 66 |

| December 2022 | 50 |

| December 2022 | 102 |

| December 2022 | 98 |

| December 2022 | 57 |

| December 2022 | 292 |

| December 2022 | 73 |

| December 2022 | 30 |

| December 2022 | 109 |

| December 2022 | 22 |

| December 2022 | 7 |

| December 2022 | 86 |

| December 2022 | 26 |

| December 2022 | 23 |

| December 2022 | 49 |

| December 2022 | 61 |

| December 2022 | 21 |

| December 2022 | 48 |

| December 2022 | 207 |

| December 2022 | 23 |

| December 2022 | 22 |

| December 2022 | 41 |

| December 2022 | 32 |

| December 2022 | 81 |

| January 2023 | 26 |

| January 2023 | 17 |

| January 2023 | 26 |

| January 2023 | 35 |

| January 2023 | 9 |

| January 2023 | 31 |

| January 2023 | 4 |

| January 2023 | 23 |

| January 2023 | 4 |

| January 2023 | 35 |

| January 2023 | 150 |

| January 2023 | 48 |

| January 2023 | 192 |

| January 2023 | 88 |

| January 2023 | 12 |

| January 2023 | 65 |

| January 2023 | 213 |

| January 2023 | 25 |

| January 2023 | 27 |

| January 2023 | 74 |

| January 2023 | 112 |

| January 2023 | 64 |

| January 2023 | 23 |

| January 2023 | 83 |

| January 2023 | 98 |

| January 2023 | 69 |

| January 2023 | 191 |

| January 2023 | 50 |

| January 2023 | 71 |

| January 2023 | 329 |

| January 2023 | 89 |

| January 2023 | 32 |

| January 2023 | 7 |

| January 2023 | 29 |

| January 2023 | 28 |

| January 2023 | 36 |

| January 2023 | 59 |

| January 2023 | 65 |

| January 2023 | 74 |

| January 2023 | 48 |

| January 2023 | 178 |

| January 2023 | 48 |

| January 2023 | 50 |

| January 2023 | 79 |

| January 2023 | 70 |

| January 2023 | 8 |

| January 2023 | 31 |

| February 2023 | 9 |

| February 2023 | 51 |

| February 2023 | 11 |

| February 2023 | 103 |

| February 2023 | 45 |

| February 2023 | 7 |

| February 2023 | 64 |

| February 2023 | 84 |

| February 2023 | 35 |

| February 2023 | 106 |

| February 2023 | 87 |

| February 2023 | 27 |

| February 2023 | 40 |

| February 2023 | 141 |

| February 2023 | 66 |

| February 2023 | 126 |

| February 2023 | 39 |

| February 2023 | 11 |

| February 2023 | 40 |

| February 2023 | 28 |

| February 2023 | 157 |

| February 2023 | 35 |

| February 2023 | 44 |

| February 2023 | 48 |

| February 2023 | 105 |

| February 2023 | 99 |

| February 2023 | 83 |

| February 2023 | 293 |

| February 2023 | 175 |

| February 2023 | 93 |

| February 2023 | 97 |

| February 2023 | 35 |

| February 2023 | 129 |

| February 2023 | 9 |

| February 2023 | 31 |

| February 2023 | 56 |

| February 2023 | 152 |

| February 2023 | 10 |

| February 2023 | 45 |

| February 2023 | 27 |

| February 2023 | 60 |

| February 2023 | 27 |

| February 2023 | 42 |

| February 2023 | 91 |

| February 2023 | 239 |

| February 2023 | 87 |

| February 2023 | 59 |

| March 2023 | 21 |

| March 2023 | 154 |

| March 2023 | 85 |

| March 2023 | 383 |

| March 2023 | 51 |

| March 2023 | 83 |

| March 2023 | 214 |

| March 2023 | 28 |

| March 2023 | 13 |

| March 2023 | 228 |

| March 2023 | 60 |

| March 2023 | 174 |

| March 2023 | 74 |

| March 2023 | 84 |

| March 2023 | 46 |

| March 2023 | 111 |

| March 2023 | 6 |

| March 2023 | 19 |

| March 2023 | 80 |

| March 2023 | 36 |

| March 2023 | 101 |

| March 2023 | 26 |

| March 2023 | 27 |

| March 2023 | 63 |

| March 2023 | 21 |

| March 2023 | 80 |

| March 2023 | 82 |

| March 2023 | 9 |

| March 2023 | 49 |

| March 2023 | 151 |

| March 2023 | 108 |

| March 2023 | 106 |

| March 2023 | 219 |

| March 2023 | 51 |

| March 2023 | 15 |

| March 2023 | 40 |

| March 2023 | 48 |

| March 2023 | 12 |

| March 2023 | 20 |

| March 2023 | 81 |

| March 2023 | 39 |

| March 2023 | 83 |

| March 2023 | 12 |

| March 2023 | 313 |

| March 2023 | 101 |

| March 2023 | 43 |

| March 2023 | 20 |

| April 2023 | 33 |

| April 2023 | 8 |

| April 2023 | 11 |

| April 2023 | 254 |

| April 2023 | 58 |

| April 2023 | 37 |

| April 2023 | 16 |

| April 2023 | 24 |

| April 2023 | 101 |

| April 2023 | 29 |

| April 2023 | 69 |

| April 2023 | 31 |

| April 2023 | 6 |

| April 2023 | 24 |

| April 2023 | 166 |

| April 2023 | 94 |

| April 2023 | 40 |

| April 2023 | 7 |

| April 2023 | 65 |

| April 2023 | 110 |

| April 2023 | 18 |

| April 2023 | 58 |

| April 2023 | 173 |

| April 2023 | 74 |

| April 2023 | 126 |

| April 2023 | 43 |

| April 2023 | 393 |

| April 2023 | 41 |

| April 2023 | 82 |

| April 2023 | 12 |

| April 2023 | 53 |

| April 2023 | 39 |

| April 2023 | 30 |

| April 2023 | 53 |

| April 2023 | 15 |

| April 2023 | 95 |

| April 2023 | 29 |

| April 2023 | 45 |

| April 2023 | 32 |

| April 2023 | 93 |

| April 2023 | 2 |

| April 2023 | 22 |

| April 2023 | 33 |

| April 2023 | 124 |

| April 2023 | 46 |

| April 2023 | 152 |

| April 2023 | 18 |

| May 2023 | 34 |

| May 2023 | 36 |

| May 2023 | 42 |

| May 2023 | 27 |

| May 2023 | 73 |

| May 2023 | 84 |

| May 2023 | 66 |

| May 2023 | 8 |

| May 2023 | 100 |

| May 2023 | 68 |

| May 2023 | 90 |

| May 2023 | 324 |

| May 2023 | 51 |

| May 2023 | 14 |

| May 2023 | 25 |

| May 2023 | 30 |

| May 2023 | 75 |

| May 2023 | 45 |

| May 2023 | 38 |

| May 2023 | 141 |

| May 2023 | 67 |

| May 2023 | 113 |

| May 2023 | 109 |

| May 2023 | 129 |

| May 2023 | 22 |

| May 2023 | 32 |

| May 2023 | 13 |

| May 2023 | 68 |

| May 2023 | 270 |

| May 2023 | 9 |

| May 2023 | 39 |

| May 2023 | 18 |

| May 2023 | 36 |

| May 2023 | 180 |

| May 2023 | 112 |

| May 2023 | 58 |

| May 2023 | 60 |

| May 2023 | 26 |

| May 2023 | 93 |

| May 2023 | 13 |

| May 2023 | 28 |

| May 2023 | 36 |

| May 2023 | 7 |

| May 2023 | 90 |

| May 2023 | 59 |

| May 2023 | 139 |

| May 2023 | 202 |

| June 2023 | 30 |

| June 2023 | 89 |

| June 2023 | 13 |

| June 2023 | 30 |

| June 2023 | 13 |

| June 2023 | 29 |

| June 2023 | 13 |

| June 2023 | 28 |

| June 2023 | 158 |

| June 2023 | 24 |

| June 2023 | 51 |

| June 2023 | 13 |

| June 2023 | 28 |

| June 2023 | 42 |

| June 2023 | 54 |

| June 2023 | 181 |

| June 2023 | 83 |

| June 2023 | 34 |

| June 2023 | 31 |

| June 2023 | 67 |

| June 2023 | 42 |

| June 2023 | 25 |

| June 2023 | 87 |

| June 2023 | 93 |

| June 2023 | 108 |

| June 2023 | 9 |

| June 2023 | 33 |

| June 2023 | 55 |

| June 2023 | 40 |

| June 2023 | 27 |

| June 2023 | 73 |

| June 2023 | 33 |

| June 2023 | 87 |

| June 2023 | 44 |

| June 2023 | 80 |

| June 2023 | 33 |

| June 2023 | 65 |

| June 2023 | 63 |

| June 2023 | 45 |

| June 2023 | 66 |

| June 2023 | 10 |

| June 2023 | 76 |

| June 2023 | 36 |

| June 2023 | 98 |

| June 2023 | 87 |

| June 2023 | 36 |

| June 2023 | 85 |

| July 2023 | 17 |

| July 2023 | 44 |

| July 2023 | 11 |

| July 2023 | 32 |

| July 2023 | 23 |

| July 2023 | 9 |

| July 2023 | 35 |

| July 2023 | 27 |

| July 2023 | 16 |

| July 2023 | 11 |

| July 2023 | 99 |

| July 2023 | 17 |

| July 2023 | 35 |

| July 2023 | 10 |

| July 2023 | 20 |

| July 2023 | 36 |

| July 2023 | 14 |

| July 2023 | 56 |

| July 2023 | 75 |

| July 2023 | 51 |

| July 2023 | 103 |

| July 2023 | 27 |

| July 2023 | 155 |

| July 2023 | 55 |

| July 2023 | 62 |

| July 2023 | 33 |

| July 2023 | 22 |

| July 2023 | 49 |

| July 2023 | 43 |

| July 2023 | 25 |

| July 2023 | 159 |

| July 2023 | 32 |

| July 2023 | 9 |

| July 2023 | 34 |

| July 2023 | 44 |

| July 2023 | 63 |

| July 2023 | 14 |

| July 2023 | 27 |

| July 2023 | 33 |

| July 2023 | 76 |

| July 2023 | 59 |

| July 2023 | 80 |

| July 2023 | 20 |

| July 2023 | 48 |

| July 2023 | 18 |

| July 2023 | 21 |

| July 2023 | 5 |

| August 2023 | 59 |

| August 2023 | 32 |

| August 2023 | 127 |

| August 2023 | 54 |

| August 2023 | 36 |

| August 2023 | 30 |

| August 2023 | 71 |

| August 2023 | 177 |

| August 2023 | 60 |

| August 2023 | 148 |

| August 2023 | 42 |

| August 2023 | 49 |

| August 2023 | 26 |

| August 2023 | 27 |

| August 2023 | 69 |

| August 2023 | 99 |

| August 2023 | 28 |

| August 2023 | 41 |

| August 2023 | 12 |

| August 2023 | 80 |

| August 2023 | 23 |

| August 2023 | 17 |

| August 2023 | 128 |

| August 2023 | 80 |

| August 2023 | 182 |

| August 2023 | 14 |

| August 2023 | 10 |

| August 2023 | 65 |

| August 2023 | 23 |

| August 2023 | 77 |

| August 2023 | 28 |

| August 2023 | 79 |

| August 2023 | 43 |

| August 2023 | 22 |

| August 2023 | 49 |

| August 2023 | 45 |

| August 2023 | 25 |

| August 2023 | 68 |

| August 2023 | 19 |

| August 2023 | 39 |

| August 2023 | 26 |

| August 2023 | 90 |

| August 2023 | 223 |

| August 2023 | 43 |

| August 2023 | 7 |

| August 2023 | 52 |

| August 2023 | 181 |

| September 2023 | 76 |

| September 2023 | 102 |

| September 2023 | 57 |

| September 2023 | 26 |

| September 2023 | 100 |

| September 2023 | 107 |

| September 2023 | 190 |

| September 2023 | 345 |

| September 2023 | 77 |

| September 2023 | 119 |

| September 2023 | 50 |

| September 2023 | 257 |

| September 2023 | 28 |

| September 2023 | 23 |

| September 2023 | 51 |

| September 2023 | 61 |

| September 2023 | 30 |

| September 2023 | 51 |

| September 2023 | 24 |

| September 2023 | 60 |

| September 2023 | 39 |

| September 2023 | 23 |

| September 2023 | 31 |

| September 2023 | 93 |

| September 2023 | 129 |

| September 2023 | 39 |

| September 2023 | 43 |

| September 2023 | 38 |

| September 2023 | 31 |

| September 2023 | 30 |

| September 2023 | 168 |

| September 2023 | 39 |

| September 2023 | 53 |

| September 2023 | 108 |

| September 2023 | 98 |

| September 2023 | 210 |

| September 2023 | 118 |

| September 2023 | 5 |

| September 2023 | 51 |

| September 2023 | 75 |

| September 2023 | 43 |

| September 2023 | 40 |

| September 2023 | 48 |

| September 2023 | 24 |

| September 2023 | 75 |

| September 2023 | 110 |

| September 2023 | 277 |

| October 2023 | 86 |

| October 2023 | 18 |

| October 2023 | 94 |

| October 2023 | 30 |

| October 2023 | 208 |

| October 2023 | 45 |

| October 2023 | 13 |

| October 2023 | 14 |

| October 2023 | 13 |

| October 2023 | 79 |

| October 2023 | 23 |

| October 2023 | 152 |

| October 2023 | 18 |

| October 2023 | 12 |

| October 2023 | 102 |

| October 2023 | 97 |

| October 2023 | 159 |

| October 2023 | 257 |

| October 2023 | 80 |

| October 2023 | 34 |

| October 2023 | 45 |

| October 2023 | 64 |

| October 2023 | 2 |

| October 2023 | 107 |

| October 2023 | 50 |

| October 2023 | 139 |

| October 2023 | 16 |

| October 2023 | 41 |

| October 2023 | 29 |

| October 2023 | 13 |

| October 2023 | 118 |

| October 2023 | 29 |

| October 2023 | 154 |

| October 2023 | 27 |

| October 2023 | 11 |

| October 2023 | 16 |

| October 2023 | 20 |

| October 2023 | 30 |

| October 2023 | 31 |

| October 2023 | 54 |

| October 2023 | 38 |

| October 2023 | 30 |

| October 2023 | 92 |

| October 2023 | 152 |

| October 2023 | 109 |

| October 2023 | 83 |

| October 2023 | 15 |

| November 2023 | 10 |

| November 2023 | 25 |

| November 2023 | 99 |

| November 2023 | 96 |

| November 2023 | 34 |

| November 2023 | 12 |

| November 2023 | 21 |

| November 2023 | 25 |

| November 2023 | 24 |

| November 2023 | 9 |

| November 2023 | 109 |

| November 2023 | 50 |

| November 2023 | 32 |

| November 2023 | 9 |

| November 2023 | 1 |

| November 2023 | 61 |

| November 2023 | 37 |

| November 2023 | 24 |

| November 2023 | 49 |

| November 2023 | 37 |

| November 2023 | 9 |

| November 2023 | 77 |

| November 2023 | 313 |

| November 2023 | 44 |

| November 2023 | 106 |

| November 2023 | 52 |

| November 2023 | 21 |

| November 2023 | 265 |

| November 2023 | 109 |

| November 2023 | 14 |

| November 2023 | 59 |

| November 2023 | 69 |

| November 2023 | 21 |

| November 2023 | 136 |

| November 2023 | 106 |

| November 2023 | 52 |

| November 2023 | 129 |

| November 2023 | 13 |

| November 2023 | 46 |

| November 2023 | 11 |

| November 2023 | 14 |

| November 2023 | 139 |

| November 2023 | 2 |

| November 2023 | 11 |

| November 2023 | 80 |

| November 2023 | 89 |

| November 2023 | 71 |

| December 2023 | 44 |

| December 2023 | 18 |

| December 2023 | 40 |

| December 2023 | 18 |

| December 2023 | 83 |

| December 2023 | 24 |

| December 2023 | 5 |

| December 2023 | 90 |

| December 2023 | 206 |

| December 2023 | 22 |

| December 2023 | 35 |

| December 2023 | 11 |

| December 2023 | 41 |

| December 2023 | 49 |

| December 2023 | 9 |

| December 2023 | 57 |

| December 2023 | 63 |

| December 2023 | 114 |

| December 2023 | 13 |

| December 2023 | 32 |

| December 2023 | 35 |

| December 2023 | 32 |

| December 2023 | 103 |

| December 2023 | 58 |

| December 2023 | 102 |

| December 2023 | 4 |

| December 2023 | 61 |

| December 2023 | 36 |

| December 2023 | 36 |

| December 2023 | 12 |

| December 2023 | 29 |

| December 2023 | 68 |

| December 2023 | 15 |

| December 2023 | 18 |

| December 2023 | 53 |

| December 2023 | 22 |

| December 2023 | 84 |

| December 2023 | 15 |

| December 2023 | 76 |

| December 2023 | 72 |

| December 2023 | 59 |

| December 2023 | 267 |

| December 2023 | 42 |

| December 2023 | 72 |

| December 2023 | 5 |

| December 2023 | 52 |

| December 2023 | 20 |

| January 2024 | 21 |

| January 2024 | 261 |

| January 2024 | 173 |

| January 2024 | 114 |

| January 2024 | 12 |

| January 2024 | 91 |

| January 2024 | 67 |

| January 2024 | 79 |

| January 2024 | 45 |

| January 2024 | 84 |

| January 2024 | 35 |

| January 2024 | 15 |

| January 2024 | 17 |

| January 2024 | 90 |

| January 2024 | 216 |

| January 2024 | 42 |

| January 2024 | 65 |

| January 2024 | 16 |

| January 2024 | 31 |

| January 2024 | 32 |

| January 2024 | 20 |

| January 2024 | 25 |

| January 2024 | 88 |

| January 2024 | 79 |

| January 2024 | 65 |

| January 2024 | 302 |

| January 2024 | 88 |

| January 2024 | 124 |

| January 2024 | 110 |

| January 2024 | 107 |

| January 2024 | 74 |

| January 2024 | 42 |

| January 2024 | 43 |

| January 2024 | 39 |

| January 2024 | 76 |

| January 2024 | 40 |

| January 2024 | 61 |

| January 2024 | 74 |

| January 2024 | 25 |

| January 2024 | 9 |

| January 2024 | 86 |

| January 2024 | 127 |

| January 2024 | 75 |

| January 2024 | 24 |

| January 2024 | 36 |

| January 2024 | 31 |

| January 2024 | 116 |

| February 2024 | 39 |

| February 2024 | 98 |

| February 2024 | 97 |

| February 2024 | 353 |

| February 2024 | 5 |

| February 2024 | 19 |

| February 2024 | 12 |

| February 2024 | 16 |

| February 2024 | 28 |

| February 2024 | 3 |

| February 2024 | 7 |

| February 2024 | 96 |

| February 2024 | 81 |

| February 2024 | 192 |

| February 2024 | 127 |

| February 2024 | 53 |

| February 2024 | 56 |

| February 2024 | 35 |

| February 2024 | 107 |

| February 2024 | 126 |

| February 2024 | 14 |

| February 2024 | 73 |

| February 2024 | 238 |

| February 2024 | 13 |

| February 2024 | 30 |

| February 2024 | 17 |

| February 2024 | 13 |

| February 2024 | 24 |

| February 2024 | 111 |

| February 2024 | 48 |

| February 2024 | 7 |

| February 2024 | 131 |

| February 2024 | 8 |

| February 2024 | 71 |

| February 2024 | 33 |

| February 2024 | 42 |

| February 2024 | 85 |

| February 2024 | 45 |

| February 2024 | 127 |

| February 2024 | 37 |

| February 2024 | 71 |

| February 2024 | 12 |

| February 2024 | 124 |

| February 2024 | 34 |

| February 2024 | 27 |

| February 2024 | 63 |

| February 2024 | 7 |

| March 2024 | 99 |

| March 2024 | 86 |

| March 2024 | 129 |

| March 2024 | 151 |

| March 2024 | 52 |

| March 2024 | 27 |

| March 2024 | 51 |

| March 2024 | 39 |

| March 2024 | 8 |

| March 2024 | 36 |

| March 2024 | 32 |

| March 2024 | 104 |

| March 2024 | 80 |

| March 2024 | 25 |

| March 2024 | 88 |

| March 2024 | 44 |

| March 2024 | 45 |

| March 2024 | 26 |

| March 2024 | 9 |

| March 2024 | 49 |

| March 2024 | 114 |

| March 2024 | 173 |

| March 2024 | 111 |

| March 2024 | 26 |

| March 2024 | 86 |

| March 2024 | 11 |

| March 2024 | 22 |

| March 2024 | 45 |

| March 2024 | 9 |

| March 2024 | 223 |

| March 2024 | 481 |

| March 2024 | 3 |

| March 2024 | 65 |

| March 2024 | 240 |

| March 2024 | 108 |

| March 2024 | 48 |

| March 2024 | 8 |

| March 2024 | 34 |

| March 2024 | 166 |

| March 2024 | 29 |

| March 2024 | 57 |

| March 2024 | 33 |

| March 2024 | 194 |

| March 2024 | 232 |

| March 2024 | 73 |

| March 2024 | 27 |

| March 2024 | 153 |

| April 2024 | 13 |

| April 2024 | 9 |

| April 2024 | 188 |

| April 2024 | 18 |

| April 2024 | 83 |

| April 2024 | 495 |

| April 2024 | 157 |

| April 2024 | 49 |

| April 2024 | 96 |

| April 2024 | 32 |

| April 2024 | 99 |

| April 2024 | 143 |

| April 2024 | 100 |

| April 2024 | 148 |

| April 2024 | 19 |

| April 2024 | 105 |

| April 2024 | 25 |

| April 2024 | 92 |

| April 2024 | 140 |

| April 2024 | 194 |

| April 2024 | 37 |

| April 2024 | 21 |

| April 2024 | 16 |

| April 2024 | 149 |

| April 2024 | 11 |

| April 2024 | 236 |

| April 2024 | 91 |

| April 2024 | 31 |

| April 2024 | 88 |

| April 2024 | 21 |

| April 2024 | 187 |

| April 2024 | 13 |

| April 2024 | 91 |

| April 2024 | 76 |

| April 2024 | 271 |

| April 2024 | 286 |

| April 2024 | 61 |

| April 2024 | 69 |

| April 2024 | 128 |

| April 2024 | 23 |

| April 2024 | 44 |

| April 2024 | 36 |

| April 2024 | 50 |

| April 2024 | 169 |

| April 2024 | 42 |

| April 2024 | 29 |

| April 2024 | 39 |

| May 2024 | 69 |

| May 2024 | 182 |

| May 2024 | 88 |

| May 2024 | 67 |

| May 2024 | 45 |

| May 2024 | 12 |

| May 2024 | 21 |

| May 2024 | 166 |

| May 2024 | 39 |

| May 2024 | 17 |

| May 2024 | 10 |

| May 2024 | 49 |

| May 2024 | 121 |

| May 2024 | 179 |

| May 2024 | 57 |

| May 2024 | 58 |

| May 2024 | 28 |

| May 2024 | 81 |

| May 2024 | 15 |

| May 2024 | 297 |

| May 2024 | 33 |

| May 2024 | 32 |

| May 2024 | 19 |

| May 2024 | 201 |

| May 2024 | 19 |

| May 2024 | 47 |

| May 2024 | 14 |

| May 2024 | 82 |

| May 2024 | 26 |

| May 2024 | 410 |

| May 2024 | 65 |

| May 2024 | 56 |

| May 2024 | 73 |

| May 2024 | 30 |

| May 2024 | 11 |

| May 2024 | 123 |

| May 2024 | 20 |

| May 2024 | 35 |

| May 2024 | 31 |

| May 2024 | 132 |

| May 2024 | 133 |

| May 2024 | 110 |

| May 2024 | 135 |

| May 2024 | 57 |

| May 2024 | 131 |

| May 2024 | 123 |

| May 2024 | 18 |

| June 2024 | 14 |

| June 2024 | 32 |

| June 2024 | 102 |

| June 2024 | 35 |

| June 2024 | 7 |

| June 2024 | 26 |

| June 2024 | 13 |

| June 2024 | 41 |

| June 2024 | 39 |

| June 2024 | 22 |

| June 2024 | 27 |

| June 2024 | 114 |

| June 2024 | 5 |

| June 2024 | 77 |

| June 2024 | 2 |

| June 2024 | 21 |

| June 2024 | 39 |

| June 2024 | 38 |

| June 2024 | 87 |

| June 2024 | 78 |

| June 2024 | 205 |

| June 2024 | 2 |

| June 2024 | 11 |

| June 2024 | 52 |

| June 2024 | 19 |

| June 2024 | 68 |

| June 2024 | 8 |

| June 2024 | 98 |

| June 2024 | 49 |

| June 2024 | 8 |

| June 2024 | 146 |

| June 2024 | 20 |

| June 2024 | 26 |

| June 2024 | 48 |

| June 2024 | 100 |

| June 2024 | 3 |

| June 2024 | 18 |

| June 2024 | 21 |

| June 2024 | 62 |

| June 2024 | 68 |

| June 2024 | 50 |

| June 2024 | 37 |

| June 2024 | 34 |

| June 2024 | 20 |

| June 2024 | 13 |

| June 2024 | 4 |

| June 2024 | 62 |

| July 2024 | 9 |

| July 2024 | 55 |

| July 2024 | 30 |

| July 2024 | 119 |

| July 2024 | 21 |

| July 2024 | 88 |

| July 2024 | 81 |

| July 2024 | 178 |

| July 2024 | 60 |

| July 2024 | 35 |

| July 2024 | 35 |

| July 2024 | 122 |

| July 2024 | 22 |

| July 2024 | 143 |

| July 2024 | 65 |

| July 2024 | 18 |

| July 2024 | 79 |

| July 2024 | 43 |

| July 2024 | 89 |

| July 2024 | 12 |

| July 2024 | 34 |

| July 2024 | 28 |

| July 2024 | 3 |

| July 2024 | 145 |

| July 2024 | 84 |

| July 2024 | 231 |

| July 2024 | 5 |

| July 2024 | 38 |

| July 2024 | 141 |

| July 2024 | 28 |

| July 2024 | 14 |

| July 2024 | 60 |

| July 2024 | 39 |

| July 2024 | 10 |

| July 2024 | 31 |

| July 2024 | 48 |

| July 2024 | 28 |

| July 2024 | 18 |

| July 2024 | 53 |

| July 2024 | 14 |

| July 2024 | 9 |

| July 2024 | 64 |

| July 2024 | 67 |

| July 2024 | 96 |

| July 2024 | 99 |

| July 2024 | 11 |

| July 2024 | 6 |

| August 2024 | 19 |

| August 2024 | 10 |

| August 2024 | 24 |

| August 2024 | 49 |

| August 2024 | 37 |

| August 2024 | 81 |

| August 2024 | 43 |

| August 2024 | 22 |

| August 2024 | 39 |

| August 2024 | 36 |

| August 2024 | 8 |

| August 2024 | 11 |

| August 2024 | 4 |

| August 2024 | 12 |

| August 2024 | 12 |

| August 2024 | 51 |

| August 2024 | 68 |

| August 2024 | 26 |

| August 2024 | 31 |

| August 2024 | 40 |

| August 2024 | 45 |

| August 2024 | 59 |

| August 2024 | 25 |

| August 2024 | 58 |

| August 2024 | 12 |

| August 2024 | 16 |

| August 2024 | 10 |

| August 2024 | 7 |

| August 2024 | 26 |

| August 2024 | 5 |

| August 2024 | 23 |

| August 2024 | 1 |

| August 2024 | 10 |

| August 2024 | 30 |

| August 2024 | 30 |

| August 2024 | 19 |

| August 2024 | 8 |

| August 2024 | 34 |

| August 2024 | 25 |

| August 2024 | 10 |

| August 2024 | 8 |

| August 2024 | 10 |

| August 2024 | 31 |

| August 2024 | 13 |

| August 2024 | 11 |

| August 2024 | 17 |

| August 2024 | 5 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on 4 April 2022 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on 30 January 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analysing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analysing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, and history.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organisation?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography, action research, phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasise different aims and perspectives.

| Approach | What does it involve? |

|---|---|

| Grounded theory | Researchers collect rich data on a topic of interest and develop theories . |

| Researchers immerse themselves in groups or organisations to understand their cultures. | |

| Researchers and participants collaboratively link theory to practice to drive social change. | |

| Phenomenological research | Researchers investigate a phenomenon or event by describing and interpreting participants’ lived experiences. |

| Narrative research | Researchers examine how stories are told to understand how participants perceive and make sense of their experiences. |

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves ‘instruments’ in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analysing the data.

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organise your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorise your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analysing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasise different concepts.

| Approach | When to use | Example |

|---|---|---|

| To describe and categorise common words, phrases, and ideas in qualitative data. | A market researcher could perform content analysis to find out what kind of language is used in descriptions of therapeutic apps. | |

| To identify and interpret patterns and themes in qualitative data. | A psychologist could apply thematic analysis to travel blogs to explore how tourism shapes self-identity. | |

| To examine the content, structure, and design of texts. | A media researcher could use textual analysis to understand how news coverage of celebrities has changed in the past decade. | |

| To study communication and how language is used to achieve effects in specific contexts. | A political scientist could use discourse analysis to study how politicians generate trust in election campaigns. |

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analysing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability