Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Don't submit your assignments before you do this

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students. Free citation check included.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved August 12, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

What exactly is a Concept Paper, and how do you write one?

Learn why a concept paper is important, what the main elements of a research concept paper are, and how to create an excellent one.

Prior to submitting a formal proposal (business proposal, product, or research proposal), many private organizations have historically asked for the submission of a concept paper for review.

Recently, organizations have begun to advocate for the usage of concept papers as a way for applicants to obtain informal input on their ideas and projects before submitting a proposal. Several of these organizations now demand a concept paper as part of the official application process.

Simply described, a concept paper is a preliminary document that explains the purpose of research, why it is being conducted, and how it will be performed. It examines a concept or idea and offers an outline of the topic that a researcher wants to pursue. Continue reading to learn more about concept papers and how to create a good one.

What a concept paper is and its purpose

A concept paper is a brief paper that outlines the important components of a research or project before it is carried out. Its purpose is to offer an overview. Entrepreneurs working on a business idea or product, as well as students and researchers, frequently write concept papers .

Researchers may be required to prepare a concept paper when submitting a project proposal to a funding authority to acquire the required grants.

As a consequence, the importance is based on the fact that it should help the examiner determine whether the research is relevant, practicable, and useful .

If not, they may suggest looking into a different research area. It also allows the examiner to assess your comprehension of the research and, as a result, if you are likely to require assistance in completing the research.

Illustrate your Concept Paper with infographics

Infographics are very useful to explain complex subjects in a very short time. Use Mind the Graph to create beautiful infographics for your Concept Paper with scientifically accurate illustrations, icons, arrows and many other design tools.

Concept paper’s elements for an academic research

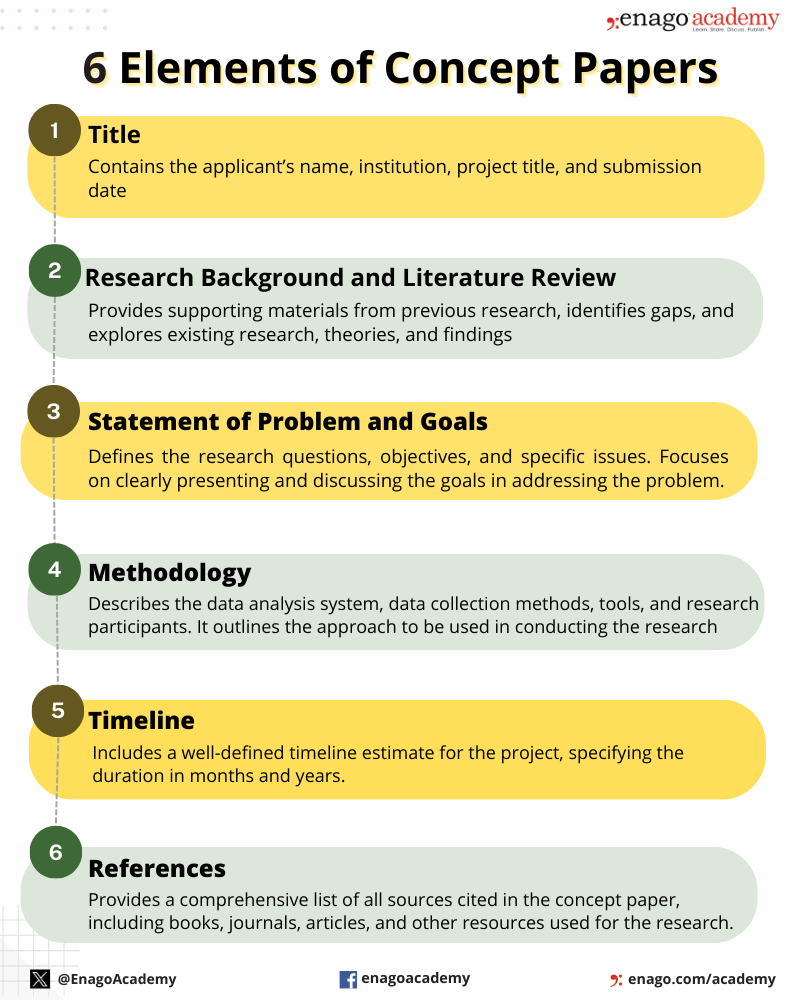

To produce an effective concept paper, you must first comprehend the essential elements of academic research:

- Title page: Mention the applicant’s name, institution, project title, and submission date.

- Background for the research: The second section should be the purpose section, which should be able to clear out what has already been stated about the subject, any gaps in information that need to be filled or problems to be solved, as well as the reason why you wish to examine the issue.

- Literature review: In this section, you should provide a theoretical basis and supporting material for your chosen subject.

- State the problem and your goals: Describe the overall problems, including the research questions and objectives. State your research’s unique and original aspects, concentrate on providing and clearly discussing your goals towards the problem.

- Methodology: Provide the data analysis system to be utilized, data collecting method, tools to be used, and research participants in this section.

- Timeline: Include a realistic timeline estimate that is defined in months and years.

- References: Add a list of all sources cited in your concept paper , such as books, journals, and other resources.

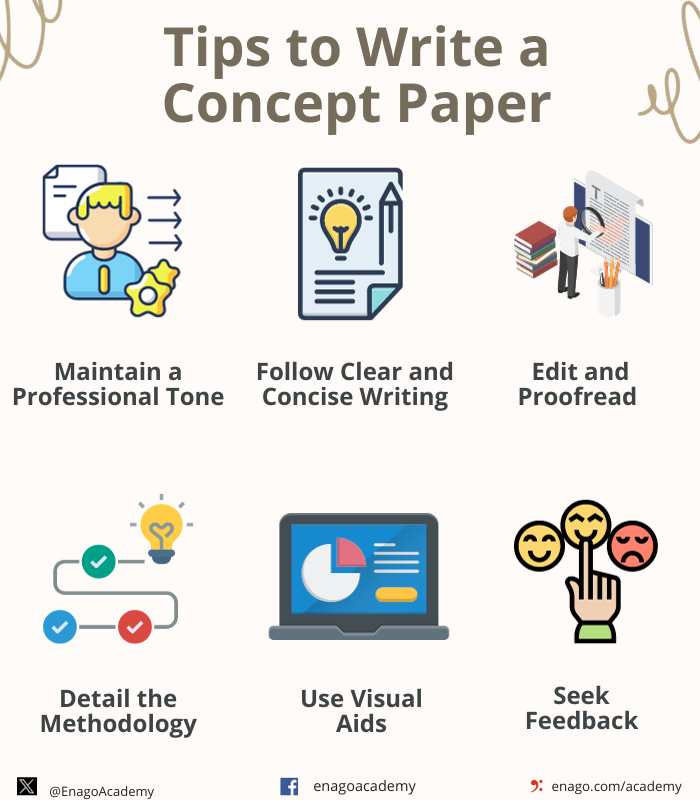

Tips on writing an effective concept paper

A concept paper is extremely crucial for a project or research, especially if it requires funding. Check out these simple tips to ensure your concept paper is successful and simple.

- Choose a research topic that truly piques your curiosity

- Create a list of research questions. The more, the merrier.

- When describing the project’s reasoning, use data and numbers.

- Use no more than 5 single-spaced pages.

- Tailor your speech to the appropriate audience.

- Make certain that the basic format elements, such as page numbers, are included.

- Spend additional time on your timeline as this section is critical for funding.

- Give specific examples of how you plan to measure your progress toward your goals.

- Provide an initial budget when seeking funds. Sponsors will want to obtain an idea of how much funds are required.

Start creating infographics and scientific illustrations

Use the power of infographics and scientific illustrations to your advantage. Including graphic assets in your work may increase your authority and highlight all of the most valuable information, ensuring that your audience is engaged and completely comprehensive of the information you are providing.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Exclusive high quality content about effective visual communication in science.

Sign Up for Free

Try the best infographic maker and promote your research with scientifically-accurate beautiful figures

no credit card required

About Jessica Abbadia

Jessica Abbadia is a lawyer that has been working in Digital Marketing since 2020, improving organic performance for apps and websites in various regions through ASO and SEO. Currently developing scientific and intellectual knowledge for the community's benefit. Jessica is an animal rights activist who enjoys reading and drinking strong coffee.

Content tags

How To Write An A-Grade Literature Review

3 straightforward steps (with examples) + free template.

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | October 2019

Quality research is about building onto the existing work of others , “standing on the shoulders of giants”, as Newton put it. The literature review chapter of your dissertation, thesis or research project is where you synthesise this prior work and lay the theoretical foundation for your own research.

Long story short, this chapter is a pretty big deal, which is why you want to make sure you get it right . In this post, I’ll show you exactly how to write a literature review in three straightforward steps, so you can conquer this vital chapter (the smart way).

Overview: The Literature Review Process

- Understanding the “ why “

- Finding the relevant literature

- Cataloguing and synthesising the information

- Outlining & writing up your literature review

- Example of a literature review

But first, the “why”…

Before we unpack how to write the literature review chapter, we’ve got to look at the why . To put it bluntly, if you don’t understand the function and purpose of the literature review process, there’s no way you can pull it off well. So, what exactly is the purpose of the literature review?

Well, there are (at least) four core functions:

- For you to gain an understanding (and demonstrate this understanding) of where the research is at currently, what the key arguments and disagreements are.

- For you to identify the gap(s) in the literature and then use this as justification for your own research topic.

- To help you build a conceptual framework for empirical testing (if applicable to your research topic).

- To inform your methodological choices and help you source tried and tested questionnaires (for interviews ) and measurement instruments (for surveys ).

Most students understand the first point but don’t give any thought to the rest. To get the most from the literature review process, you must keep all four points front of mind as you review the literature (more on this shortly), or you’ll land up with a wonky foundation.

Okay – with the why out the way, let’s move on to the how . As mentioned above, writing your literature review is a process, which I’ll break down into three steps:

- Finding the most suitable literature

- Understanding , distilling and organising the literature

- Planning and writing up your literature review chapter

Importantly, you must complete steps one and two before you start writing up your chapter. I know it’s very tempting, but don’t try to kill two birds with one stone and write as you read. You’ll invariably end up wasting huge amounts of time re-writing and re-shaping, or you’ll just land up with a disjointed, hard-to-digest mess . Instead, you need to read first and distil the information, then plan and execute the writing.

Step 1: Find the relevant literature

Naturally, the first step in the literature review journey is to hunt down the existing research that’s relevant to your topic. While you probably already have a decent base of this from your research proposal , you need to expand on this substantially in the dissertation or thesis itself.

Essentially, you need to be looking for any existing literature that potentially helps you answer your research question (or develop it, if that’s not yet pinned down). There are numerous ways to find relevant literature, but I’ll cover my top four tactics here. I’d suggest combining all four methods to ensure that nothing slips past you:

Method 1 – Google Scholar Scrubbing

Google’s academic search engine, Google Scholar , is a great starting point as it provides a good high-level view of the relevant journal articles for whatever keyword you throw at it. Most valuably, it tells you how many times each article has been cited, which gives you an idea of how credible (or at least, popular) it is. Some articles will be free to access, while others will require an account, which brings us to the next method.

Method 2 – University Database Scrounging

Generally, universities provide students with access to an online library, which provides access to many (but not all) of the major journals.

So, if you find an article using Google Scholar that requires paid access (which is quite likely), search for that article in your university’s database – if it’s listed there, you’ll have access. Note that, generally, the search engine capabilities of these databases are poor, so make sure you search for the exact article name, or you might not find it.

Method 3 – Journal Article Snowballing

At the end of every academic journal article, you’ll find a list of references. As with any academic writing, these references are the building blocks of the article, so if the article is relevant to your topic, there’s a good chance a portion of the referenced works will be too. Do a quick scan of the titles and see what seems relevant, then search for the relevant ones in your university’s database.

Method 4 – Dissertation Scavenging

Similar to Method 3 above, you can leverage other students’ dissertations. All you have to do is skim through literature review chapters of existing dissertations related to your topic and you’ll find a gold mine of potential literature. Usually, your university will provide you with access to previous students’ dissertations, but you can also find a much larger selection in the following databases:

- Open Access Theses & Dissertations

- Stanford SearchWorks

Keep in mind that dissertations and theses are not as academically sound as published, peer-reviewed journal articles (because they’re written by students, not professionals), so be sure to check the credibility of any sources you find using this method. You can do this by assessing the citation count of any given article in Google Scholar. If you need help with assessing the credibility of any article, or with finding relevant research in general, you can chat with one of our Research Specialists .

Alright – with a good base of literature firmly under your belt, it’s time to move onto the next step.

Need a helping hand?

Step 2: Log, catalogue and synthesise

Once you’ve built a little treasure trove of articles, it’s time to get reading and start digesting the information – what does it all mean?

While I present steps one and two (hunting and digesting) as sequential, in reality, it’s more of a back-and-forth tango – you’ll read a little , then have an idea, spot a new citation, or a new potential variable, and then go back to searching for articles. This is perfectly natural – through the reading process, your thoughts will develop , new avenues might crop up, and directional adjustments might arise. This is, after all, one of the main purposes of the literature review process (i.e. to familiarise yourself with the current state of research in your field).

As you’re working through your treasure chest, it’s essential that you simultaneously start organising the information. There are three aspects to this:

- Logging reference information

- Building an organised catalogue

- Distilling and synthesising the information

I’ll discuss each of these below:

2.1 – Log the reference information

As you read each article, you should add it to your reference management software. I usually recommend Mendeley for this purpose (see the Mendeley 101 video below), but you can use whichever software you’re comfortable with. Most importantly, make sure you load EVERY article you read into your reference manager, even if it doesn’t seem very relevant at the time.

2.2 – Build an organised catalogue

In the beginning, you might feel confident that you can remember who said what, where, and what their main arguments were. Trust me, you won’t. If you do a thorough review of the relevant literature (as you must!), you’re going to read many, many articles, and it’s simply impossible to remember who said what, when, and in what context . Also, without the bird’s eye view that a catalogue provides, you’ll miss connections between various articles, and have no view of how the research developed over time. Simply put, it’s essential to build your own catalogue of the literature.

I would suggest using Excel to build your catalogue, as it allows you to run filters, colour code and sort – all very useful when your list grows large (which it will). How you lay your spreadsheet out is up to you, but I’d suggest you have the following columns (at minimum):

- Author, date, title – Start with three columns containing this core information. This will make it easy for you to search for titles with certain words, order research by date, or group by author.

- Categories or keywords – You can either create multiple columns, one for each category/theme and then tick the relevant categories, or you can have one column with keywords.

- Key arguments/points – Use this column to succinctly convey the essence of the article, the key arguments and implications thereof for your research.

- Context – Note the socioeconomic context in which the research was undertaken. For example, US-based, respondents aged 25-35, lower- income, etc. This will be useful for making an argument about gaps in the research.

- Methodology – Note which methodology was used and why. Also, note any issues you feel arise due to the methodology. Again, you can use this to make an argument about gaps in the research.

- Quotations – Note down any quoteworthy lines you feel might be useful later.

- Notes – Make notes about anything not already covered. For example, linkages to or disagreements with other theories, questions raised but unanswered, shortcomings or limitations, and so forth.

If you’d like, you can try out our free catalog template here (see screenshot below).

2.3 – Digest and synthesise

Most importantly, as you work through the literature and build your catalogue, you need to synthesise all the information in your own mind – how does it all fit together? Look for links between the various articles and try to develop a bigger picture view of the state of the research. Some important questions to ask yourself are:

- What answers does the existing research provide to my own research questions ?

- Which points do the researchers agree (and disagree) on?

- How has the research developed over time?

- Where do the gaps in the current research lie?

To help you develop a big-picture view and synthesise all the information, you might find mind mapping software such as Freemind useful. Alternatively, if you’re a fan of physical note-taking, investing in a large whiteboard might work for you.

Step 3: Outline and write it up!

Once you’re satisfied that you have digested and distilled all the relevant literature in your mind, it’s time to put pen to paper (or rather, fingers to keyboard). There are two steps here – outlining and writing:

3.1 – Draw up your outline

Having spent so much time reading, it might be tempting to just start writing up without a clear structure in mind. However, it’s critically important to decide on your structure and develop a detailed outline before you write anything. Your literature review chapter needs to present a clear, logical and an easy to follow narrative – and that requires some planning. Don’t try to wing it!

Naturally, you won’t always follow the plan to the letter, but without a detailed outline, you’re more than likely going to end up with a disjointed pile of waffle , and then you’re going to spend a far greater amount of time re-writing, hacking and patching. The adage, “measure twice, cut once” is very suitable here.

In terms of structure, the first decision you’ll have to make is whether you’ll lay out your review thematically (into themes) or chronologically (by date/period). The right choice depends on your topic, research objectives and research questions, which we discuss in this article .

Once that’s decided, you need to draw up an outline of your entire chapter in bullet point format. Try to get as detailed as possible, so that you know exactly what you’ll cover where, how each section will connect to the next, and how your entire argument will develop throughout the chapter. Also, at this stage, it’s a good idea to allocate rough word count limits for each section, so that you can identify word count problems before you’ve spent weeks or months writing!

PS – check out our free literature review chapter template…

3.2 – Get writing

With a detailed outline at your side, it’s time to start writing up (finally!). At this stage, it’s common to feel a bit of writer’s block and find yourself procrastinating under the pressure of finally having to put something on paper. To help with this, remember that the objective of the first draft is not perfection – it’s simply to get your thoughts out of your head and onto paper, after which you can refine them. The structure might change a little, the word count allocations might shift and shuffle, and you might add or remove a section – that’s all okay. Don’t worry about all this on your first draft – just get your thoughts down on paper.

Once you’ve got a full first draft (however rough it may be), step away from it for a day or two (longer if you can) and then come back at it with fresh eyes. Pay particular attention to the flow and narrative – does it fall fit together and flow from one section to another smoothly? Now’s the time to try to improve the linkage from each section to the next, tighten up the writing to be more concise, trim down word count and sand it down into a more digestible read.

Once you’ve done that, give your writing to a friend or colleague who is not a subject matter expert and ask them if they understand the overall discussion. The best way to assess this is to ask them to explain the chapter back to you. This technique will give you a strong indication of which points were clearly communicated and which weren’t. If you’re working with Grad Coach, this is a good time to have your Research Specialist review your chapter.

Finally, tighten it up and send it off to your supervisor for comment. Some might argue that you should be sending your work to your supervisor sooner than this (indeed your university might formally require this), but in my experience, supervisors are extremely short on time (and often patience), so, the more refined your chapter is, the less time they’ll waste on addressing basic issues (which you know about already) and the more time they’ll spend on valuable feedback that will increase your mark-earning potential.

Literature Review Example

In the video below, we unpack an actual literature review so that you can see how all the core components come together in reality.

Let’s Recap

In this post, we’ve covered how to research and write up a high-quality literature review chapter. Let’s do a quick recap of the key takeaways:

- It is essential to understand the WHY of the literature review before you read or write anything. Make sure you understand the 4 core functions of the process.

- The first step is to hunt down the relevant literature . You can do this using Google Scholar, your university database, the snowballing technique and by reviewing other dissertations and theses.

- Next, you need to log all the articles in your reference manager , build your own catalogue of literature and synthesise all the research.

- Following that, you need to develop a detailed outline of your entire chapter – the more detail the better. Don’t start writing without a clear outline (on paper, not in your head!)

- Write up your first draft in rough form – don’t aim for perfection. Remember, done beats perfect.

- Refine your second draft and get a layman’s perspective on it . Then tighten it up and submit it to your supervisor.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

38 Comments

Thank you very much. This page is an eye opener and easy to comprehend.

This is awesome!

I wish I come across GradCoach earlier enough.

But all the same I’ll make use of this opportunity to the fullest.

Thank you for this good job.

Keep it up!

You’re welcome, Yinka. Thank you for the kind words. All the best writing your literature review.

Thank you for a very useful literature review session. Although I am doing most of the steps…it being my first masters an Mphil is a self study and one not sure you are on the right track. I have an amazing supervisor but one also knows they are super busy. So not wanting to bother on the minutae. Thank you.

You’re most welcome, Renee. Good luck with your literature review 🙂

This has been really helpful. Will make full use of it. 🙂

Thank you Gradcoach.

Really agreed. Admirable effort

thank you for this beautiful well explained recap.

Thank you so much for your guide of video and other instructions for the dissertation writing.

It is instrumental. It encouraged me to write a dissertation now.

Thank you the video was great – from someone that knows nothing thankyou

an amazing and very constructive way of presetting a topic, very useful, thanks for the effort,

It is timely

It is very good video of guidance for writing a research proposal and a dissertation. Since I have been watching and reading instructions, I have started my research proposal to write. I appreciate to Mr Jansen hugely.

I learn a lot from your videos. Very comprehensive and detailed.

Thank you for sharing your knowledge. As a research student, you learn better with your learning tips in research

I was really stuck in reading and gathering information but after watching these things are cleared thanks, it is so helpful.

Really helpful, Thank you for the effort in showing such information

This is super helpful thank you very much.

Thank you for this whole literature writing review.You have simplified the process.

I’m so glad I found GradCoach. Excellent information, Clear explanation, and Easy to follow, Many thanks Derek!

You’re welcome, Maithe. Good luck writing your literature review 🙂

Thank you Coach, you have greatly enriched and improved my knowledge

Great piece, so enriching and it is going to help me a great lot in my project and thesis, thanks so much

This is THE BEST site for ANYONE doing a masters or doctorate! Thank you for the sound advice and templates. You rock!

Thanks, Stephanie 🙂

This is mind blowing, the detailed explanation and simplicity is perfect.

I am doing two papers on my final year thesis, and I must stay I feel very confident to face both headlong after reading this article.

thank you so much.

if anyone is to get a paper done on time and in the best way possible, GRADCOACH is certainly the go to area!

This is very good video which is well explained with detailed explanation

Thank you excellent piece of work and great mentoring

Thanks, it was useful

Thank you very much. the video and the information were very helpful.

Good morning scholar. I’m delighted coming to know you even before the commencement of my dissertation which hopefully is expected in not more than six months from now. I would love to engage my study under your guidance from the beginning to the end. I love to know how to do good job

Thank you so much Derek for such useful information on writing up a good literature review. I am at a stage where I need to start writing my one. My proposal was accepted late last year but I honestly did not know where to start

Like the name of your YouTube implies you are GRAD (great,resource person, about dissertation). In short you are smart enough in coaching research work.

This is a very well thought out webpage. Very informative and a great read.

Very timely.

I appreciate.

Very comprehensive and eye opener for me as beginner in postgraduate study. Well explained and easy to understand. Appreciate and good reference in guiding me in my research journey. Thank you

Thank you. I requested to download the free literature review template, however, your website wouldn’t allow me to complete the request or complete a download. May I request that you email me the free template? Thank you.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

How to Write a PhD Concept Paper

A concept paper – or concept note – is one of the initial requirements of a PhD programme. It is normally written during the PhD application process as well as early on in the programme once a student has been admitted.

A concept paper is basically a shorter version of a research proposal – in most cases between 2,000 and 2,500 words – that expresses the research ideas of the potential PhD student.

Besides being short, it should be concise yet have adequate details to convince the Department the student is applying to that he/she is worth being admitted to the programme.

Example of a title with a sub-title

References/bibliography, why do phd programmes require applicants to submit a concept paper.

A concept paper serves four main purposes:

- It gives the Department the student is applying to an idea of the student’s research interests.

- Based on point one, it informs the Department whether the student will be a good fit to the Department or not. To be a good fit, the research interests of the applicant should match those of the Department’s faculty.

- Based on the two points above, it enables the Department to offer support to the student throughout his/her PhD studies in the form of supervision and mentorship.

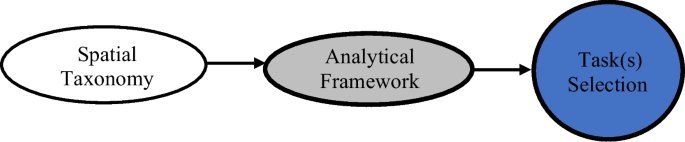

- Because the concept paper is written – and must be accepted – before the full proposal, it saves the student time and effort that would otherwise be spent on topics that may end up being rejected by the Department. A concept paper is therefore the first step to writing the PhD thesis/dissertation (see the figure below).

Format of a PhD Concept Paper

The format of a concept paper might vary from one university to another. A PhD student should therefore read the guidelines provided by his/her University of interest before writing a concept paper.

In general, the following is a common format of a concept paper:

Title of proposed study

The title of the proposed study is the first element of a concept paper.

The title should describe what the study is about by highlighting the variables of the study and the relationship between the variables if applicable.

The title should be short and specific: it is best to have a title that is not more than 15 words’ long.

Example of a title:

Use of Mobile Phone Applications for Weight Management in the United States

In order to add more specificity to the title, you can add a subtitle to the main title. The title and subtitle should be separated by a full colon.

Use of Mobile Phone Applications for Weight Management in the United States:

A Behavioural Economics’ Analysis

Background to the study

The background to the study contains the following elements:

- The history of the topic, both globally and in the proposed location of your study.

- What other researchers have found out from their own studies.

- What the gaps in the existing literature are, that is, what the other researchers have not addressed.

- What your study will contribute towards filling the identified gaps.

The implication of the above is that one must have conducted some literature review prior to writing the background to the study.

Statement of the problem

The statement of the problem is a clear description of the issue that the study will address, the relevance of the issue, the importance (benefits) of addressing the issue, and the method the researcher will use to address the issue.

Goal and objectives of the study

Once you have identified the problem of your study, the next step is to write the goal and objectives of the study. There is a difference between these two:

The goal of the study is a broad statement of what the researcher hopes to accomplish at the end of the study. The goal should also be related to the problem statement.

Any given project should have one goal because having many goals would lead to confusion. However, that one goal can have multiple elements in it, which would be accomplished through the project’s objectives.

The objectives of the study, on the other hand, are specific and detailed statements of how the researcher will go about accomplishing the stated goal.

The objectives should:

- Support the accomplishment of the goal.

- Follow a sequence, that is, like a step-by-step order. This will help you frame the activities needed to be undertaken in a logical manner so that the goal is achieved.

- Be stated using action verbs, for instance, “to identify”, “to create”, “to establish”, “to measure”, etc.

- Be about 3-4: having too few of objectives will limit the scope of your PhD dissertation, while having too many objectives may complicate the dissertation.

- Be SMART, that is, Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Time-bound.

The video below clearly explains how to set SMART goals and objectives:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MAhs-m6cNzY

Important tip 1: depending on your PhD programme, you may be required to have at least 3 journal papers to qualify for graduation. Each of your objectives can be converted into a separate journal paper on its own.

Research questions and hypotheses

Every PhD dissertation needs research questions. Research questions will help the student stay focused on his/her research.

The aim of the research is to provide answers to the research questions. The answers to the questions will form the thesis statement.

Examples of research questions:

In the title example given earlier about use of mobile phone applications for weight management in the United States, a student may be interested in the following questions:

- To what extent do adults in the United States use mobile phone applications to manage their weight?

- Is there any gender disparity in the use of mobile phone apps for weight management in the United States?

- How effective are mobile apps for weight management in the United States?

Good research questions are those that can be explored deeply and widely as well as defended using evidence. Questions with ‘yes” or “no” responses are not academic-worthy.

When developing research questions, you also need to think about the data that will be required to answer the questions. Do you have access to that data? If no, will your time and financial resources allow you to collect that data?

Important tip 2: Your PhD study is time-limited therefore data requirement issues need to be thought through at the initial stages of your concept paper writing so that you don’t waste too much time either collecting the data in the future or trying to access the data if it already exists elsewhere.

Preliminary literature review

At the concept paper stage, a preliminary literature review serves three main purposes:

- It shows whether you have knowledge of the current state of debate about your chosen topic.

- It shows whether you are familiar with the experts in your chosen topic.

- It also helps you identify the research gaps.

Proposed research design, methods and procedures

This sections provides a brief overview of the research methodology that you will adopt in your study. Some issues to consider include:

- Will your study use quantitative, qualitative or mixed-methods approach?

- Will you use secondary or primary data?

- What will be the sources of your data? Will you need any ethical clearance from your university before collecting data?

- Will the data sources be readily accessible?

- Will you use external assistance for data collection? Or will you do all the data collection yourself?

- How will the data be analysed? Which softwares will you use? Are you competent in those softwares?

While the above issues are important to think through, please note that the research design and methods will be informed by your research objectives and research questions. As an illustration:

A research question that aims to measure the effect of one (or more) variable(s) on another variable will definitely require quantitative research methods.

On the other hand, a research question that aims to explain the existence of a phenomenon will render itself to the use of qualitative research methods.

Contribution to knowledge

This is perhaps the most important aspect of a PhD dissertation. Your concept note needs to briefly highlight how your project will add value to knowledge.

Making significant contribution to knowledge at the PhD level does not mean a Nobel prize standard of knowledge (this you can do after your PhD when you’ll have all the time in the world to do so). You can achieve this in various ways:

- New applications of existing ideas.

- New interpretations of previous ideas.

- Investigating an existing issue in a new location.

- Development of a new theory.

- Coming up with a new technique, among others.

The last section of the concept paper is the reference list or bibliography. This is the section that lists the literatures that you have reviewed and cited in your paper.

There is a slight difference between a reference list and a bibliography:

A reference list includes all those studies that have been directly cited in the paper.

A bibliography, on the other hand, includes all those studies that have been directly cited in the paper as well as those that were reviewed and consulted but not cited in the paper.

When creating the reference list/bibliography, one should be mindful of the referencing style that is required by their PhD department (that is, whether APA, MLA, Chicago, Havard, etc).

Final Thoughts on Writing a PhD Concept Paper

The concept paper is the first step to writing the PhD dissertation. Once accepted, the student will proceed to writing the proposal, which will then be defended before proceeding with writing the full dissertation.

The concept paper is a mini-proposal and has most of the components expected in the proposal.

However, the concept paper should be short and precise while at the same time have adequate information to enable the PhD Committee of the PhD Programme the student is applying to judge if the student will be a good fit to the programme or not.

Related posts

How To Choose a Research Topic For Your PhD Thesis (7 Key Factors to Consider)

Comprehensive Guidelines for Writing a PhD Thesis Proposal (+ free checklist for PhD Students)

Grace Njeri-Otieno

Grace Njeri-Otieno is a Kenyan, a wife, a mom, and currently a PhD student, among many other balls she juggles. She holds a Bachelors' and Masters' degrees in Economics and has more than 7 years' experience with an INGO. She was inspired to start this site so as to share the lessons learned throughout her PhD journey with other PhD students. Her vision for this site is "to become a go-to resource center for PhD students in all their spheres of learning."

Recent Content

SPSS Tutorial #12: Partial Correlation Analysis in SPSS

Partial correlation is almost similar to Pearson product-moment correlation only that it accounts for the influence of another variable, which is thought to be correlated with the two variables of...

SPSS Tutorial #11: Correlation Analysis in SPSS

In this post, I discuss what correlation is, the two most common types of correlation statistics used (Pearson and Spearman), and how to conduct correlation analysis in SPSS. What is correlation...

- How it works

"Christmas Offer"

Terms & conditions.

As the Christmas season is upon us, we find ourselves reflecting on the past year and those who we have helped to shape their future. It’s been quite a year for us all! The end of the year brings no greater joy than the opportunity to express to you Christmas greetings and good wishes.

At this special time of year, Research Prospect brings joyful discount of 10% on all its services. May your Christmas and New Year be filled with joy.

We are looking back with appreciation for your loyalty and looking forward to moving into the New Year together.

"Claim this offer"

In unfamiliar and hard times, we have stuck by you. This Christmas, Research Prospect brings you all the joy with exciting discount of 10% on all its services.

Offer valid till 5-1-2024

We love being your partner in success. We know you have been working hard lately, take a break this holiday season to spend time with your loved ones while we make sure you succeed in your academics

Discount code: RP23720

Published by Nicolas at January 17th, 2024 , Revised On January 23, 2024

What Is A Preliminary Literature Review

Embarking on a research journey requires careful planning and a solid foundation of knowledge about the existing body of work related to the chosen topic. One crucial step in this process is the preliminary literature review, a comprehensive examination of previously published research that lays the groundwork for a successful study.

Table of Contents

This blog will help you understand what is a preliminary literature review, its purpose, and how to write one.

What Is A Preliminary Literature Review – Definition

A preliminary literature review is a comprehensive survey of existing scholarly works, articles, books, and other sources that are relevant to a particular research topic or question. This type of literature review is conducted at the beginning of a research project to gain an understanding of the existing knowledge in the field and to identify gaps, trends, and key concepts that will inform the researcher’s own study.

Purpose Of A Preliminary Literature Review

The purpose of a preliminary literature review is to:

Establish A Foundation

It helps researchers familiarize themselves with the existing literature related to their research topic and thesis statement . This foundation is crucial for understanding the context and background of the subject.

Identify Gaps And Trends

By reviewing existing literature, researchers can identify gaps in current knowledge or areas where further research is needed. They can also identify trends, controversies, and debates within the field.

Refine Research Questions And Objectives

The information gathered from the literature review in a thesis or a dissertation helps researchers refine their research questions and objectives. It allows them to tailor their study to contribute meaningfully to the existing body of knowledge.

Avoid Duplication

Researchers can ensure they are not duplicating efforts by conducting a preliminary literature review. This step helps them understand what has already been studied and published.

Build A Theoretical Framework

The literature review aids in constructing a theoretical framework for the study by highlighting relevant theories and concepts that will guide the research.

Support Methodological Choices

It provides insights into the methodologies used in previous studies, helping researchers make informed decisions about their own research methods.

Structure Of A Preliminary Literature Review

The structure of a preliminary literature review generally follows a systematic and organized approach. While specific requirements may vary based on academic disciplines or the nature of the research paper , here is a general structure that can be adapted:

Introduction

- Introduce the research topic or question.

- Provide context for the importance of the topic.

- State the purpose of the literature review.

Scope And Objectives

- Define the scope of the literature review (e.g., specific time frame, geographic area, key concepts).

- Clearly state the objectives of the literature review.

Search Strategy

- Describe the methods used to search for relevant literature (databases, keywords, inclusion/exclusion criteria).

- Explain the rationale for the chosen search strategy.

Selection Criteria

Specify the criteria used to select the literature for review (e.g., peer-reviewed journals, recent publications, relevance to research questions).

Organization Of The Review

- Group literature by themes, concepts, or methodologies.

- Provide a rationale for the chosen organizational structure.

Synthesis Of Key Findings

- Summarize the main findings from each selected source to further strengthen your hypothesis .

- Highlight key concepts, theories, methodologies, and gaps in the literature.

Critical Evaluation

- Critically assess the strengths and weaknesses of each source.

- Consider the credibility, reliability, and validity of the research presented.

Identification Of Gaps And Trends

- Identify gaps or limitations in the existing meta synthesis literature .

- Highlight trends, patterns, or recurring themes across different studies.

Theoretical Framework

- Integrate relevant theories and frameworks that emerge from the literature.

- Discuss how existing theories inform the research question.

Methodological Insights

- Summarize the methodologies employed in previous studies.

- Discuss the implications of these methodologies for the current research.

Implications For Research

- Discuss how the literature review findings inform the current research’s design and objectives.

- Highlight potential contributions to the field.

- Summarize the key points of the literature review.

- Emphasize the significance of the literature review in guiding the current research paper format .

The literature review we write have:

- Precision and Clarity

- Zero Plagiarism

- High-level Encryption

- Authentic Sources

Tips For Effectively Writing A Preliminary Literature Review

Now that you are familiar with what is a preliminary literature review and its structure, here are some tips to help you write a literature review that is informative, well-organized, and contributes to the overall success of your research:

Tip 1: Define Clear Objectives

Clearly articulate the objectives of your literature review. What are you trying to achieve? What questions do you want to answer? Defining clear objectives will guide your literature search and organization.

Tip 2: Create A Well-Defined Scope

Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Consider factors such as the time frame, geographic focus, and specific concepts or variables you are interested in. A well-defined scope helps you manage the breadth of your review.

Tip 3: Organize Your Review Logically

Organize the literature logically by themes, concepts, or methodologies. Consider whether a chronological, thematic, or methodological organization best suits your research objectives.

Tip 4: Use A Systematic Search Strategy

Develop a systematic search strategy to find relevant literature. Use appropriate databases, keywords, and inclusion/exclusion criteria. Document your search process to enhance transparency and reproducibility.

Tip 5: Keep Detailed Records

Keep detailed records of the sources you consult. Include bibliographic information, summaries of key findings, and notes on the methodology. This will save time and help you keep track of your sources.

Tip 6: Critically Evaluate Each Source

Provide a critical evaluation of each source. Assess the credibility, reliability, and validity of the research presented. Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of each study.

Tip 7: Synthesize Key Findings

Synthesize key findings from each source. Summarize the main concepts, theories, and methodologies. Identify common themes and patterns across different studies.

Tip 8: Highlight Gaps And Trends

Clearly identify gaps or limitations in the existing literature. Highlight trends, patterns, or recurring themes. Discuss how these gaps and trends inform your research objectives.

Tip 9: Connect Sources And Concepts

Show how different sources and concepts connect to each other. Demonstrate the relationships between studies and how they contribute to the overall understanding of the research topic.

Tip 10: Build A Theoretical Framework

Integrate relevant theories and frameworks that emerge from the literature. Discuss how existing theories inform your research questions and objectives.

Tip 11: Maintain Cohesiveness

Ensure that your literature review maintains a cohesive and logical flow. Each section should contribute to an understanding of the existing knowledge related to your research topic.

Tip 12: Use Clear And Concise Language

Write in clear and concise language. Avoid unnecessary jargon and ensure that your writing is accessible to a broad audience. Clearly communicate your ideas and findings.

Tip 13: Revise And Edit

Review, revise, and edit your literature review. Check for clarity, coherence, and consistency. Ensure that your review meets the requirements of your academic or research context.

Tip 14: Seek Feedback

Seek feedback from peers, mentors, or colleagues. Getting input from others can help you identify areas for improvement and ensure the quality of your literature review.

What Is A Preliminary Literature Review Example

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health: A Preliminary Literature Review

Social media has become an integral part of daily life, transforming the way individuals communicate, share information, and connect with others. As this digital landscape continues to evolve, there is a growing concern about its potential impact on mental health. This literature review aims to explore existing research on the relationship between social media use and mental health outcomes.

Social Media Use and Mental Health

Several studies have highlighted a positive correlation between excessive social media use and increased levels of anxiety and depression (Smith, 2018; Jones et al., 2019). The constant exposure to curated content and social comparisons on platforms like Instagram and Facebook may contribute to heightened feelings of inadequacy and stress.

Research indicates a strong association between cyberbullying on social media and adverse psychological outcomes in both adolescents and adults (Williams & Johnson, 2020; Wang et al., 2017). The anonymity and widespread reach of social media platforms amplify the negative impact of online harassment.

Social Media Addiction and Mental Health

The concept of social media addiction has gained attention in recent years, with studies suggesting a link between excessive social media use and addictive behaviours (Kuss & Griffiths, 2017; Andreassen et al., 2019). The constant need for validation and engagement may contribute to a cycle of dependency, adversely affecting mental well-being.

Positive Aspects and Moderators

Contrary to the negative associations, some studies emphasize the positive role of social media in fostering social support and connection (Primack et al., 2020; Ellison et al., 2014). Platforms like Twitter and online support groups may enhance social ties and provide emotional support, thereby positively influencing mental health.

Research suggests that the way individuals use social media may be a crucial factor in determining its impact on mental health (Verduyn et al., 2017; Twenge & Campbell, 2018). Passive consumption and excessive scrolling may contribute to negative outcomes, while active engagement and meaningful interactions could have a protective effect.

While existing literature presents a nuanced picture of the relationship between social media use and mental health, it is clear that further research is needed to understand the underlying mechanisms and potential moderating factors. This preliminary review highlights the need for a comprehensive examination of both the positive and negative aspects of social media in shaping mental health outcomes.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a preliminary literature review.

A preliminary literature review is an initial survey of existing academic sources on a specific topic to identify key themes, gaps, and debates. It provides a foundation for further research and helps researchers understand the current state of knowledge on the subject.

How to write a preliminary literature review?

To write a preliminary literature review, define your research topic, search for relevant academic sources, summarize key findings, and identify patterns or gaps. Organize the information coherently, highlighting existing debates and areas requiring further exploration.

How to write a preliminary literature review example?

When writing a preliminary literature review, begin by introducing the research topic. Summarize key findings from relevant sources, highlighting themes and gaps. Conclude with a brief assessment of the existing knowledge, paving the way for future research.

What is the meaning of preliminary literature review?

A preliminary literature review is an early-stage examination of existing academic works on a specific topic. It helps researchers understand current scholarship, identify gaps or trends, and lay the groundwork for a more comprehensive review in the later stages of the research process.

You May Also Like

What is a manuscript? A manuscript is a written or typed document, often the original draft of a book or article, before publication, undergoing editing and revisions.

The central idea of this excerpt revolves around the exploration of key themes, offering insights that illuminate the concepts within the text.

Mediating variables explain the relationship, while moderating variables influence its strength or direction under different conditions.

Ready to place an order?

USEFUL LINKS

Learning resources.

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jun 20, 2024 9:08 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

Concept Papers in Research: Deciphering the blueprint of brilliance

Concept papers hold significant importance as a precursor to a full-fledged research proposal in academia and research. Understanding the nuances and significance of a concept paper is essential for any researcher aiming to lay a strong foundation for their investigation.

Table of Contents

What Is Concept Paper

A concept paper can be defined as a concise document which outlines the fundamental aspects of a grant proposal. It outlines the initial ideas, objectives, and theoretical framework of a proposed research project. It is usually two to three-page long overview of the proposal. However, they differ from both research proposal and original research paper in lacking a detailed plan and methodology for a specific study as in research proposal provides and exclusion of the findings and analysis of a completed research project as in an original research paper. A concept paper primarily focuses on introducing the basic idea, intended research question, and the framework that will guide the research.

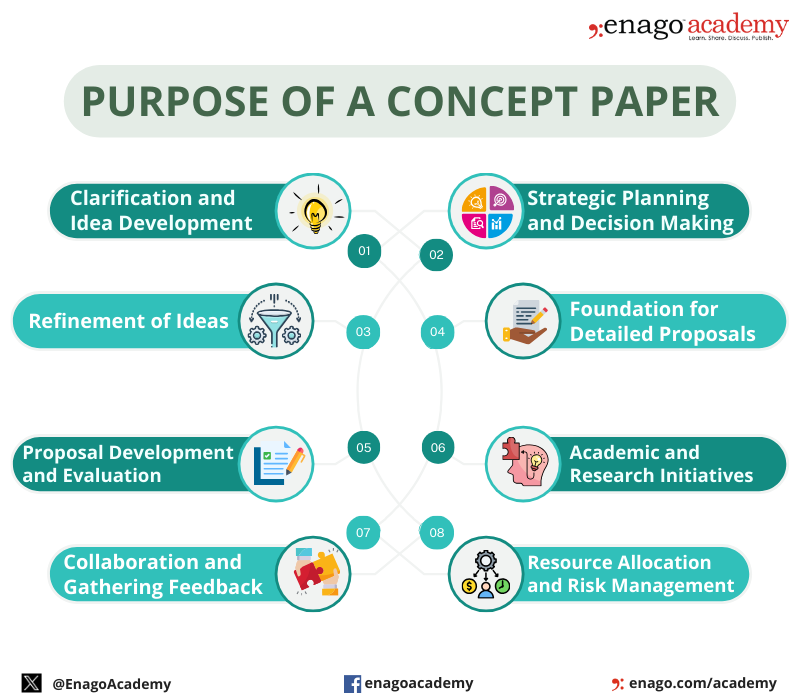

Purpose of a Concept Paper

A concept paper serves as an initial document, commonly required by private organizations before a formal proposal submission. It offers a preliminary overview of a project or research’s purpose, method, and implementation. It acts as a roadmap, providing clarity and coherence in research direction. Additionally, it also acts as a tool for receiving informal input. The paper is used for internal decision-making, seeking approval from the board, and securing commitment from partners. It promotes cohesive communication and serves as a professional and respectful tool in collaboration.

These papers aid in focusing on the core objectives, theoretical underpinnings, and potential methodology of the research, enabling researchers to gain initial feedback and refine their ideas before delving into detailed research.

Key Elements of a Concept Paper

Key elements of a concept paper include the title page , background , literature review , problem statement , methodology, timeline, and references. It’s crucial for researchers seeking grants as it helps evaluators assess the relevance and feasibility of the proposed research.

Writing an effective concept paper in academic research involves understanding and incorporating essential elements:

How to Write a Concept Paper?

To ensure an effective concept paper, it’s recommended to select a compelling research topic, pose numerous research questions and incorporate data and numbers to support the project’s rationale. The document must be concise (around five pages) after tailoring the content and following the formatting requirements. Additionally, infographics and scientific illustrations can enhance the document’s impact and engagement with the audience. The steps to write a concept paper are as follows:

1. Write a Crisp Title:

Choose a clear, descriptive title that encapsulates the main idea. The title should express the paper’s content. It should serve as a preview for the reader.

2. Provide a Background Information:

Give a background information about the issue or topic. Define the key terminologies or concepts. Review existing literature to identify the gaps your concept paper aims to fill.

3. Outline Contents in the Introduction:

Introduce the concept paper with a brief overview of the problem or idea you’re addressing. Explain its significance. Identify the specific knowledge gaps your research aims to address and mention any contradictory theories related to your research question.

4. Define a Mission Statement:

The mission statement follows a clear problem statement that defines the problem or concept that need to be addressed. Write a concise mission statement that engages your research purpose and explains why gaining the reader’s approval will benefit your field.

5. Explain the Research Aim and Objectives:

Explain why your research is important and the specific questions you aim to answer through your research. State the specific goals and objectives your concept intends to achieve. Provide a detailed explanation of your concept. What is it, how does it work, and what makes it unique?

6. Detail the Methodology:

Discuss the research methods you plan to use, such as surveys, experiments, case studies, interviews, and observations. Mention any ethical concerns related to your research.

7. Outline Proposed Methods and Potential Impact:

Provide detailed information on how you will conduct your research, including any specialized equipment or collaborations. Discuss the expected results or impacts of implementing the concept. Highlight the potential benefits, whether social, economic, or otherwise.

8. Mention the Feasibility

Discuss the resources necessary for the concept’s execution. Mention the expected duration of the research and specific milestones. Outline a proposed timeline for implementing the concept.

9. Include a Support Section:

Include a section that breaks down the project’s budget, explaining the overall cost and individual expenses to demonstrate how the allocated funds will be used.

10. Provide a Conclusion:

Summarize the key points and restate the importance of the concept. If necessary, include a call to action or next steps.

Although the structure and elements of a concept paper may vary depending on the specific requirements, you can tailor your document based on the guidelines or instructions you’ve been given.

Here are some tips to write a concept paper:

Example of a Concept Paper

Here is an example of a concept paper. Please note, this is a generalized example. Your concept paper should align with the specific requirements, guidelines, and objectives you aim to achieve in your proposal. Tailor it accordingly to the needs and context of the initiative you are proposing.

Download Now!

Importance of a Concept Paper

Concept papers serve various fields, influencing the direction and potential of research in science, social sciences, technology, and more. They contribute to the formulation of groundbreaking studies and novel ideas that can impact societal, economic, and academic spheres.

A concept paper serves several crucial purposes in various fields:

In summary, a well-crafted concept paper is essential in outlining a clear, concise, and structured framework for new ideas or proposals. It helps in assessing the feasibility, viability, and potential impact of the concept before investing significant resources into its implementation.

How well do you understand concept papers? Test your understanding now!

Fill the Details to Check Your Score