Community Programs to Promote Youth Development (2002)

Chapter: 10 conclusions and recommendations, chapter 10 conclusions and recommendations.

I n recent years, a number of social forces have changed both the landscape of family and community life and the expectations for young people. A combination of factors have weakened the informal community support once available to young people: high rates of family mobility; greater anonymity in neighborhoods, where more parents are at work and out of the home and neighborhood for long periods, and in schools, which have become larger and much more heterogeneous; extensive media exposure to themes of violence and heavy use and abuse of drugs and alcohol; and, in some cases, the deterioration and disorganization of neighborhoods and schools as a result of crime, drugs, and poverty. At the same time, today’s world has become increasingly complex, technical, and multicultural, placing new and challenging demands on young people in terms of education, training, and the social and emotional skills needed in a highly competitive environment. Finally, the length of adolescence has extended to the mid- to late twenties, and the pathways to adulthood have become less clear and more numerous. In addition, many youth are entering the labor market with inadequate knowledge and such skills as the ability to communicate effectively, resolve conflicts, and prepare for and succeed in a job.

Concerns about youth are at the center of many policy debates. The future well-being of the country depends on raising a new generation of skilled, competent, and responsible adults. Yet at least 25 percent of adolescents in the United States are at serious risk of not achieving “productive adulthood” and face such risks as substance abuse, adolescent pregnancy, school failure, and involvement with the juvenile justice system. Depending on their circumstances and choices, they may carry those risks into their adult lives. Public investments in programs to counter such trends have grown significantly over the past decade or so. For the most part, these efforts have targeted specific problems and threats to young people. Substantial public health investments have been made to prevent teen smoking, sexually transmitted diseases, and other health risks. Major funding has been allocated to the prevention and control of juvenile delinquency and youth crime.

This report has explored the research and evaluation on adolescent development and community programs for youth. This chapter presents the committee’s primary conclusions and recommendations. We had the task of considering various aspects related to community programs for youth—from developing a general understanding of adolescent development, the needs of youth, and the fundamental nature of these programs, to critically examining the research, evaluation, and data instruments they use. We have organized the conclusions and recommendations around two primary themes: (1) policy and practice and (2) research, evaluation, and data collection.

POLICY AND PRACTICE

The committee began its work by drawing up a set of core concepts about adolescents that serve as a foundation for this report.

Some youth are doing very well. The good news for many young people is that many measures of adolescent well-being have shown significant improvement since the late 1980s. Young people are increasingly graduating from high school and enrolling in higher education. Almost half of the high school seniors participate in community service. Most young people are participating in physical exercise. Serious violent crime committed by adolescents, some illicit drug use, and teen pregnancy are down.

Some youth are taking dangerous risks and doing poorly. Some social indicators suggest continuing problems, particularly for minority youth living in poor communities and youth living in poor, single-parent

families. Youth from poor inner-city and rural areas are doing substantially worse on national achievement tests than youth from more affluent school districts. School dropout is particularly high among Hispanic youth and adolescents living in poor communities. Many young women and men are engaging in unsafe sex, exposing them to sexually transmitted infections. Smoking cigarettes, obesity, and gun violence on school campuses have all increased.

All young people need a variety of experiences to develop to their full potential. All youth need an array of experiences to reduce risk-taking and promote both current well-being and successful transition into adulthood. Such experiences include opportunities to learn skills, to make a difference in their community, to interact with youth from multicultural backgrounds, to have experiences in leadership and shared decision making, and to make strong connections with nonfamilial adults. These experiences are important to all young people, regardless of racial or ethnic group, socioeconomic status, or special needs.

Some young people have unmet needs and are particularly at risk of participating in problem behaviors. Young people who have the most severe unmet needs in their lives are particularly in jeopardy of participating in risk behaviors, such as dropping out of school, participating in violent behavior, or using drugs and alcohol. Young people with the most severe unmet needs often live in very poor and high-risk neighborhoods with few opportunities to get the critical experiences needed for positive development. They are often experience repeated racial and ethnic discrimination. Such youth have a substantial amount of free, unsupervised time during their nonschool hours. Other youth who are in special need of more programs include youth with disabilities of all kinds, youth from troubled family situations, and youth with special needs for places to find emotional support.

Promoting Adolescent Development at the Program Level

Understanding adolescent development and the factors contributing to the healthy development of all young people is critical to the design and implementation of community programs for youth. A priority of the committee’s work was identifying what is necessary for adolescents to be happy, healthy, and productive at the present time, as well as successful, contributing adults in the future.

Adolescence is a time of great change: biological changes associated with puberty, major social changes associated with transitions between

grade levels and changing roles and expectations, and major psychological changes linked to increasing social and cognitive maturity. With so many rapid changes comes a heightened potential for both positive and negative outcomes. Although most individuals pass through this developmental period without excessive problems, a substantial number experience difficulty.

The committee reviewed the basic tenets of human development, particularly during adolescence, and summarized the key characteristics of adolescent development. We focused on aspects of adolescent development and successful transitions to adulthood that have implications for program and policy design.

Beyond eliminating problems, the committee agreed that young people need skills, knowledge, and a variety of other personal and social assets to function well during adolescence and adulthood. But deciding what constitutes positive youth development is quite complex. Many characteristics were considered, and the committee recognized that selecting any particular set involved judgments regarding what is good. Nonetheless, longitudinal research does provide support for the links of some youth characteristics to subsequent positive adult outcomes. We were able to agree that there are some universal needs—such as the need to feel competent, to be socially connected, and to have one’s physical needs taken care of—that provide a basis for suggesting a set of assets and experiences very likely to be important for well-being. We also agreed that the failure to have these needs met is very likely to have negative consequences for well-being. We also agreed that there is extensive cultural specificity in exactly how these needs are met, as well as in the exact nature of how the assets are manifested in particular individuals. This means that the local cultural context must be taken into account as programs are designed and evaluated.

Based on a review of theory, practical experiences, and empirical research in the fields of psychology, anthropology, sociology, and others, the committee identified a set of personal and social assets that both represent healthy development and well-being during adolescence and facilitate successful transitions from childhood, through adolescence, and into adulthood. We grouped these assets into four broad developmental domains: physical, intellectual, psychological and emotional, and social development. Box ES-1 summarizes the four domains and specifies the assets within each.

Conclusions

Individuals do not necessarily need the entire range of assets to thrive; in fact, various combinations of assets across domains reflect equally positive adolescent development.

Having more assets is better than having few. Although strong assets in one category can offset weak assets in another category, life is easier to manage if one has assets in all four domains.

Continued exposure to positive experiences, settings, and people, as well as abundant opportunities to gain and refine life skills, supports young people in the acquirsition and growth of these assets.

The committee recognized that very little research directly specifies what programs can do to facilitate development, let alone how to tailor it to the needs of individual adolescents and diverse cultural groups. Few studies have applied the critical standards of science to evaluate which features of community programs influence development.

Despite these limitations, there is a broad base of knowledge about how development occurs that can and should be drawn on. Research demonstrates that certain features of the settings that adolescents experience make a tremendous difference, for good or for ill, in their lives. There is good evidence that personal and social assets develop in developmental settings that incorporate the features listed below and in Table ES-1 . The exact implementation of these features, however, needs to vary across programs, with their diverse clientele and differing constraints and missions. Young people develop positive personal and social assets in settings that have the following features:

Physical and psychological safety and security;

Structure that is developmentally appropriate, with clear expectations for behavior as well as increasing opportunities to make decisions, to participate in governance and rule-making, and to take on leadership roles as one matures and gains more expertise;

Emotional and moral support;

Opportunities for adolescents to experience supportive adult relationships;

Opportunities to learn how to form close, durable human relationships with peers that support and reinforce healthy behaviors;

Opportunities to feel a sense of belonging and being valued;

Opportunities to develop positive social values and norms;

Opportunities for skill building and mastery;

Opportunities to develop confidence in one’s abilities to master one’s environment (a sense of personal efficacy);

Opportunities to make a contribution to one’s community and to develop a sense of mattering; and

Strong links between families, schools, and broader community resources.

Since these features typically work together in synergistic ways, programs with more features are likely to provide better supports for young people’s positive development.

Although all of these features are key to the success of children and adolescents at all ages, specific settings may focus their priorities differently to meet the developmental needs of particular participants—for example, younger children need more adult-directed structure and supervision than older youth and the skills that one needs to learn in childhood are different from those that need to be learned in adolescence. Supportive, developmental settings, as a result, must be designed to be appropriate over time for different ages and to allow the setting to change in developmentally appropriate ways as participants mature. Positive development is also best supported by a wide variety of these experiences and opportunities in all of the settings in which adolescents live—the family, the school, the peer group, and the community. Still, exposure to such opportunities in community programs can compensate for lack of such opportunities in other settings.

Community programs can expand the opportunities for youth to acquire personal and social assets and to experience the broad range of features of positive developmental settings.

Programs can also fill gaps in the opportunities available in specific adolescents’ lives. Among other things, these programs can incorporate opportunities for physical, cognitive, and social and emotional development; opportunities to deal with issues of ethnic identity, sexual identity, and intergroup relationships; opportunities for community involvement and service; and opportunities to interact with caring adults and a diversity of peers who hold positive social norms and have high life goals and expectations.

Recommendation 1 —Community programs for youth should be based on a developmental framework that supports the acquisition of personal and social assets in an environment and through activities that promote both current adolescent well-being and future successful transitions to adulthood.

Serving Diverse Youth at the Community Level

Community programs are provided by many different individual organizations, each with their own unique approach and programmatic activities. They may be provided by local affiliates of large national youth-serving organizations or may be an independent organization that is affiliated with a public institution, such as a school or public library. They also may be small, autonomous grassroots organizations that exist independently in a community.

The focus of the activities may be sports and recreation, faith-based lessons, music and dance, academic enrichment, or workforce preparation. Programs may be targeted only to girls or only to boys; to a particular ethnic or religious group; or to young people with special interests. In addition, programs differ in their objectives, and some may choose to give more emphasis to particular program features.

Community-wide organizing of youth policies, as well as support for individual programs, also varies from community to community. Where there is a community infrastructure for support, the organizing body in a community might be the mayor’s office, a local government agency, or a community foundation. It might be a private intermediary organization or an individual charismatic leader, such as a minister or a rabbi of a local religious institution. However, it is often the case that there is no single person or group that is responsible for either monitoring the range and quality of community programs for youth or making sure that information about community programs is easily accessible to members of the community.

Adolescents in communities that are rich in developmental opportunities for them experience reduced risk and show evidence of higher rates of positive development. A diversity of program opportunities in each community is more likely to support broad adolescent development

and attract the interest of and meet the needs of a greater number of youth.

The complex characteristics of adolescent development and the increasing diversity of the country make the heterogeneity of young people in communities both a norm and a challenge. Therefore, effective programs must be flexible enough to adapt to this existing diversity among the young people they serve and the communities in which they operate. Even with the best staff and best funding, no single program can serve all young people or incorporate all of the features of positive developmental settings. A diversity of program opportunities in each community is more likely to support broad adolescent development and attract the interest of and meet the needs of a greater number of youth.

To provide for the most appropriate kinds of community programs for the diversity of youth in a community, communities should regularly assess the needs of adolescents and families and review available opportunities for their young people. While individual communities will invariably answer this challenge differently and make different judgments about the most appropriate ways to meet adolescent and community needs, there are several specific steps that the committee recommends be taken to support this kind of community mapping and monitoring.

Recommendation 2 —Communities should provide an ample array of program opportunities that appeal to and meet the needs of diverse youth, and should do so through local entities that can coordinate such work across the entire community. Particular attention should be placed on programs for disadvantaged and underserved youth.

Recommendation 3 —To increase the likelihood that an ample array of program opportunities will be available, communities should put in place some locally appropriate mechanism for monitoring the availability, accessability, and quality of programs for youth in their community.

Recommendation 4 —Private and public funders should provide the resources needed at the community level to develop and support community-wide programming that is orderly, coordinated, and evaluated in reasonable ways. In addition to support at the community level, this is likely to involve support for intermediary organizations and collaborative teams that include researchers, practitioners, funders, and policy makers.

RESEARCH, EVALUATION, AND DATA COLLECTION

The multiple groups concerned about community programs for youth—policy makers, families, program developers and practitioners, program staff, and young people themselves—have in common the fundamental desire to know whether programs make a difference in the lives of young people, their families, and their communities. Some are interested in learning about the effectiveness of specific details in a program; others about the effects of a given program; others about the overall effect of a set of programs together; and others about the effects of related kinds of programs. Research, program evaluation, and social indicator data can play a significant role in answering such questions, improving the design and delivery of programs, and thereby, improving the well-being and future success of young people.

The committee first reviewed research on both adolescent development and the features of positive developmental settings that support it. In both cases, the research base is just becoming comprehensive enough to allow for tentative conclusions about the individual assets that characterize positive development and features of settings that support it. The committee used a variety of criteria to suggest the tentative lists of both important individual-level assets and features of settings that support positive development outlined in Box ES-1 and Table ES-1 . These suggestions are based on scientific evidence from both short- and long-term experimental and observational studies, one-time large-scale survey studies, and longitudinal survey studies reviewed by the committee. However, much more comprehensive work is needed.

More comprehensive longitudinal and experimental research, that either builds on current efforts or involves new efforts, is needed on a wider range of populations that follows children and adolescents well into adulthood in order to understand which assets are most important to adolescent development and which patterns of assets are linked to particular types of successful adult transitions in various cultural contexts.

The list of features of positive settings, as well as both personal and social assets, that the committee has developed is provisional, the boundaries between the features are fuzzy, and the specific names given to each feature and asset reflect the terminology of the scientific disciplines in which the research was done. Research on a diverse group of adolescents followed well into adulthood is needed to understand which patterns of assets best predict successful adult transitions in various cultural contexts and how these assets work together in supporting both current and future well-being and success. Longitudinal research meets these objectives by collecting extensive psychological, social, and contextual information on the same individuals at different points in time. More experimental research that focuses on changing specific assets and characteristics of settings assumed to affect other assets is also needed in order to test causal hypotheses more sensitively.

Despite its limitations, research in all settings in the lives of adolescents—families, schools, and communities—is yielding consistent evidence that there are specific features of settings that support positive youth development and that these features can be incorporated into community programs.

Community programs have the potential to provide opportunities for youth to acquire personal and social assets and have important experiences that may be missing or are in short supply in the other settings of their lives. Whether they are packaged as teen pregnancy prevention programs, mental health programs, or youth development programs, such programs can lead to positive outcomes for youth. There is limited research, however, measuring the impact of these experiences on the development of young people and therefore limited evidence on why program effects are or are not obtained. Few researchers have applied the critical standards of science to evaluate which features of community programs influence development, which processes within each activity are related to these outcomes, and which combinations of features are best for which outcomes. Thus, there is very little research that will help organizations decide how they should tailor program activities to the needs of individual youth and diverse cultural groups.

Consequently, research is needed to sharpen the conceptualization of features of community programs and to explore whether other key features should be added to the list. This work should focus on how

different populations are affected by different program components and features (e.g., age, gender, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, community environment, developmental readiness, personality, sexual orientation, skill levels). It should also focus on how to incorporate these features into community programs and on how to maintain them once they are in place. Finally, such research should identify program strategies, resource needs, and approaches to staff training and retention that can cultivate and support the features of positive developmental settings in community programs for youth.

In the committee’s judgment, current evidence supports the replication of a few specific integrated programs for positive youth development: the Teen Outreach Program, Big Brothers Big Sisters, and Quantum Opportunities are three prime examples.

Very few integrated programs have received the kind of comprehensive experimental evaluation necessary to make a firm recommendation about replicating the program in its entirety across the country. However, there is sufficient evidence from a variety of sources to make recommendations about some fundamental principles of supportive developmental settings and some specific aspects of programs that can be used to design community programs for youth. These are captured by the features of supportive settings outlined in Table ES-1 .

Recommendation 5 —Federal agencies that fund research on adolescent health, development, and well-being, such as the Department of Health and Human Services, the Department of Justice, and the Department of Education, should build into their portfolios new or more comprehensive longitudinal and experimental research on the personal and social assets needed to promote the healthy development and well-being of adolescents and to promote the successful transition from childhood through adolescence and into adulthood.

Recommendation 6 —Public and private funders should support research on whether the features of positive developmental settings identified in this report are the most important features of community programs for youth. This research should encourage program design and implementation that meets the diverse needs of an increasingly heterogeneous population of youth.

Program Evaluation

Evaluation and ongoing program study can provide important insights to inform program design, selection, and modification. Program evaluation can also help funders and policy makers make informed choices about which programs to fund for which groups of youth. The desire to conduct high-quality evaluation can help program staff clarify their objectives and decide which types of evidence will be most useful in determining if these objectives have been met. Ongoing program study and evaluation can also be used by program staff, program participants, and funders to track program objectives; this is typically done by establishing a system for ongoing data collection that measures the extent to which various aspects of the programs are being delivered, how are they delivered, who is providing these services, and who is receiving them. Such information can provide useful information to program staff to help them make changes to improve program effectiveness. Finally, program evaluation can test both new and very well developed program designs by assessing the immediate, observable results of the program outcomes and benefits associated with participation in the program.

Such summative evaluation can be done in conjunction with strong theory-based evaluation or as a more preliminary assessment of the potential usefulness of novel programs and quite complex social experiments in which there is no well-specified theory of change. In other words, program evaluation and study can help foster accountability, determine whether programs make a difference, and provide staff with the information they need to improve service delivery.

Clearly there are many purposes for evaluation. Not surprisingly then, there are different opinions among service practitioners, researchers, policy makers, and funders about the most appropriate and useful methods for evaluating community programs for youth. In part, these disagreements reflect different goals and different questions about youth programs. In part, they reflect philosophical differences about the purposes of evaluation and nature of program development. Program practitioners, policy makers, program evaluators, and others studying programs should decide exactly which questions they want answered before deciding on the most appropriate methods. The most comprehensive experimental evaluation, which involves assessment of the quality of implementation as well as outcomes, is quite expensive and involves a variety of methods. It also provides the most comprehensive information regarding both the effectiveness of specific programs and the reasons for their effectiveness.

Very few high-quality comprehensive experimental evaluations of community programs for youth have adequately assessed the impact of the programs on adolescents.

This is presumably due to many factors—including the low priority accorded to evaluation by organizations struggling to fund services; inadequate funding for such evaluations and overreliance on program staff to conduct such evaluation, despite the fact that they have limited training to conduct such evaluations and limited time and funds to devote to such an effort; ethical concerns among practitioners and policy makers about the random assignment of some youth to programs and others to a control group receiving no services; unrealistic demands by many program funders for quick answers about the impact of programs they fund; and scarcity of the type of collaborative teams involving the research, practice, and policy communities needed to design and implement high-quality, comprehensive experimentally based evaluations. Comprehensive experimental evaluation takes time, money, and technical knowledge—features not always plentiful within agencies providing services to youth.

Some high-quality experimental and quasi-experimental evaluations show positive effects on a variety of outcomes, including both increases in the psychological and social assets of youth and decreases in the incidence of such problem behaviors as early pregnancy, drug use, and delinquent behavior.

Usually, as expected given the complexity of the behaviors being assessed and the wide range of influences on these behaviors, these effects are small for the population being studied. Nonetheless, at the individual level, the effects can be quite large and life-transforming. Such impacts are rarely reported in standard experimental evaluations, because their goal is to estimate the average effect size. Most of these evaluations also tell us little about which components of programs are the most important contributors to the positive results, the cost-effectiveness of the programs, or the reasons why programs fail.

Randomized trial experimental evaluation is often recommended as the best method for assessing whether a program influences youth development, but this design can be costly, and time-consuming and may not always be the most useful and most appropriate method of study. In

addition, unless coupled with an evaluation of the implementation and with methods designed to assess the reasons for the experimental effects, experimental evaluations by themselves provide only limited information about a program’s effectiveness.

Experimental designs are still the best method for estimating the impact of a program on its participants and should be used when this is the goal of the evaluation.

Comprehensive program evaluation is an even better way to gather complete information about programs. It requires asking a number of questions through various methods. The committee identified six fundamental questions that should be considered in comprehensive evaluations:

Is the theory of the program that is being evaluated explicit and plausible?

How well has the program theory been implemented in the sites studied?

In general, is the program effective and, in particular, is it effective with specific subpopulations of young people?

Whether it is or is not effective, why is this the case?

What is the value of the program?

What recommendations about action should be made?

All six questions may not be answered well in one study; several evaluations may be needed to address these questions. Thus comprehensive experimental evaluation can be quite expensive and time-consuming—but it provides the most information about program design, as well as fundamental questions about human development. Thus, it is particularly useful to both the policy and research communities, as well as the practice community.

In order to generate the kind of information about community programs for youth needed to justify large-scale expenditures on programs and to further fundamental understanding of role of community programs in youth development, comprehensive experimental program evaluations should be used when:

the object of study is a program component that repeatedly occurs across many of the organizations currently providing community services to youth;

an established national organization provides the program being evaluated through many local affiliates; and

theoretically sound ideas for a new demonstration program or project emerge, and pilot work indicates that these ideas can be implemented in other contexts.

Comprehensive experimental evaluations are usually not appropriate for newer, less established programs or programs that lack a well-articulated theory of change underlying the program design. A variety of nonexperimental methods, such as interviewing, case studies, and observational techniques, and more focused experimental and quasi-experimental studies are ways to understand and assess these types of community programs for youth. Although the nonexperimental methods tell us less about the effectiveness of particular community programs than experimental program evaluations, they can, when carefully implemented, provide information about the strengths and weakness in program implementation and can be used to identify patterns of effective practice. They are also quite helpful in generating hypotheses about why programs fail.

Programs that meet the following criteria should be studied through nonexperimental or more focused experimental and quasi-experimental methods, depending on the goals of the evaluation:

An organization, program, project, or program element that has not matured sufficiently in terms of its philosophy and implementation;

The evaluation has to be conducted by the staff of the program under evaluation;

The major questions of interest pertain to the quality of the program theory, the implementation of that theory, or to the nature of its participants, staff, or surrounding context;

The program is quite broad, involving multiple agencies in the same community; and

The program or organization is interested in reflective practice and continuing improvement.

Whether experimental or nonexperimental methods are used, high-quality, comprehensive evaluation is important to the future development and success of community programs for youth and should be used by all programs and youth-serving organizations.

Recommendation 7 —All community programs for youth should undergo evaluation—possibly multiple evaluations—to improve design and implementation, to create accountability, and to assess outcomes and impacts. For any given evaluation, the scope and the rigor should be appropriately calibrated to the attributes of the program, the available resources, and the goals of the evaluation.

Recommendation 8 —Funders should provide the necessary funds for evaluation. In many cases, this will involve support for collaborative teams of researchers, evaluators, theoreticians, policy makers, and practitioners to ensure that programs are well designed initially and then evaluated in the most appropriate way.

Data Collection and Social Indicators

Over the past decade, social indicator data and technical assistance resources have become increasingly important tools that community programs can employ to support every aspect of their work—from initial planning and design, to tracking goals, program accountability, targeting services, reflection, and improvement. There are now significant data and related technical assistance resources to aid in understanding the young people involved in these programs. Community programs for youth benefit from ready access to high-quality data that allow them to assess and monitor the well-being of youth in their community, the well-being of youth they directly serve, and the elements of their programs that are intended to support those youth. They also benefit from information and training to help them use these data tools wisely and effectively.

Even when exploited to their full potential, administrative, vital statistics, and related data sources can cover only limited geographic areas and only some components of a youth development framework. Adding local survey data in diverse communities, as has been done in a number of states and individual communities, can help create a more complete picture.

Community programs for youth are interested in building their capacity to assess the quality of their programs. To produce useful process

evaluations, performance monitoring, and self-assessment, however, program practitioners need valid, reliable indicators of the developmental quality of the experiences they provide. Such information would also facilitate the ability of communities to monitor change over time as new program initiatives are introduced into the community. If communities know how their youth are doing on a variety of indicators for an extended period of time both before and after a new program is introduced, they can use this information as preliminary evidence that their program is effective. Such inferences are strengthened if information on the same indicators is available in comparable communities that did not introduce that program at the same time. Research is needed to determine whether appropriate indicators vary depending on the characteristics of the specific youth population served by a program and as understanding of the determinants of positive youth development improves, these indicators should be periodically revisited and, if necessary, revised.

Many community programs also lack staff knowledge and the funds to take full advantage of social indicators as tools to aid in planning, monitoring, assessing, and improving program activities. Individual programs and communities would benefit from opportunities to increase their capacity to collect and use social indicator data.

Recommendation 9 —Public and private funders should support the fielding of youth development surveys in more states and communities around the country; the development, testing, and fielding of new youth development measures that work well across diverse population subgroups; and greater coordination between measures used in community surveys and national longitudinal surveys.

Recommendation 10 —Public and private funders should support collaboration between researchers and the practice community to develop social indicator data that build understanding of how programs are implemented and improve the ability to monitor programs. Collaborative efforts would further the understanding of the relationship between program features and positive developmental outcomes among young people.

Recommendation 11 —Public and private funders should provide opportunities for individual programs and communities to improve their capacity to collect and use social indicator data. This requires better training for program staff and more support for national and regional

intermediaries that provide technical assistance in a variety of ways, including Internet-based systems.

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

The desire among program practitioners, policy makers, scholars, scientists, parents, and society to make sure young people are healthy, happy, safe, and productive is not new. Offering formal and informal programs in the community for adolescents during nonschool hours is not new. These programs have a long history of providing positive opportunities to keep youth safe and to facilitate their development and well-being. Various individuals and professional organizations are committed to better understanding these programs and providing technical assistance to encourage their success.

The scientific evidence that elucidates the ways in which community programs for youth provide opportunities to promote adolescent development and well-being, however, is less well developed. This report has explored these programs from this perspective and presented a set of recommendations targeted at various stakeholders: practitioners (program developers, practitioners, managers, and staff); community leaders (staff and leaders in a mayor’s office, local government agencies, community foundations, private intermediaries, as well as individual community leaders); and national leaders (public and private funders, policy makers, researchers, and evaluators). The recommendations in this report have the potential to enhance existing community programs for youth, promote adolescent development among diverse groups of youth and varied communities, and increase knowledge about the links between community programs for youth and adolescent development.

After-school programs, scout groups, community service activities, religious youth groups, and other community-based activities have long been thought to play a key role in the lives of adolescents. But what do we know about the role of such programs for today's adolescents? How can we ensure that programs are designed to successfully meet young people's developmental needs and help them become healthy, happy, and productive adults?

Community Programs to Promote Youth Development explores these questions, focusing on essential elements of adolescent well-being and healthy development. It offers recommendations for policy, practice, and research to ensure that programs are well designed to meet young people's developmental needs.

The book also discusses the features of programs that can contribute to a successful transition from adolescence to adulthood. It examines what we know about the current landscape of youth development programs for America's youth, as well as how these programs are meeting their diverse needs.

Recognizing the importance of adolescence as a period of transition to adulthood, Community Programs to Promote Youth Development offers authoritative guidance to policy makers, practitioners, researchers, and other key stakeholders on the role of youth development programs to promote the healthy development and well-being of the nation's youth.

READ FREE ONLINE

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

Switch between the Original Pages , where you can read the report as it appeared in print, and Text Pages for the web version, where you can highlight and search the text.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Adv Med Educ Pract

Development and evaluation of a community immersion program during preclinical medical studies: a 15-year experience at the University of Geneva Medical School

P chastonay.

1 Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine, University of Geneva, Faculty of Medicine, Geneva, Switzerland

2 Unit of Development and Research in Medical Education, University of Geneva, Faculty of Medicine, Geneva, Switzerland

3 Nutrition and Dietetics Department, University of Applied Sciences, Geneva, Switzerland

4 Swiss School of Public Health, Zurich, Switzerland

5 Department of Neurosciences, University of Geneva, Faculty of Medicine, Geneva, Switzerland

Significant changes in medical education have occurred in recent decades because of new challenges in the health sector and new learning theories and practices. This might have contributed to the decision of medical schools throughout the world to adopt community-based learning activities. The community-based learning approach has been promoted and supported by the World Health Organization and has emerged as an efficient learning strategy. The aim of the present paper is to describe the characteristics of a community immersion clerkship for third-year undergraduate medical students, its evolution over 15 years, and an evaluation of its outcomes.

A review of the literature and consensus meetings with a multidisciplinary group of health professionals were used to define learning objectives and an educational approach when developing the program. Evaluation of the program addressed students’ perception, achievement of learning objectives, interactions between students and the community, and educational innovations over the years.

The program and the main learning objectives were defined by consensus meetings among teaching staff and community health workers, which strengthened the community immersion clerkship. Satisfaction, as monitored by a self-administered questionnaire in successive cohorts of students, showed a mean of 4.4 on a five-point scale. Students also mentioned community immersion clerkship as a unique community experience. The learning objectives were reached by a vast majority of students. Behavior evaluation was not assessed per se, but specific testimonies show that students have been marked by their community experience. The evaluation also assessed outcomes such as educational innovations (eg, students teaching other students), new developments in the curriculum (eg, partnership with the University of Applied Health Sciences), and interaction between students and the community (eg, student development of a website for a community health institution).

The community immersion clerkship trains future doctors to respond to the health problems of individuals in their complexity, and strengthens their ability to work with the community.

Significant changes in medical education have occurred over recent decades due to new challenges in the health sector and new learning theories. 1 The upcoming generation of physicians will be confronted with professional challenges, such as management of complex health problems, care of patients from different cultural backgrounds, and the need to work as team players in collaboration with other health professionals. 2 Indeed, future physicians will be expected to be not only good clinicians, but also to be capable of working in and with the community, collecting epidemiological data, planning health promotion interventions, promoting screening programs, and understanding the communities their patients live in. 3 , 4

This might have contributed to the decision of medical schools throughout the world to adopt community-based learning activities, 5 with some emblematic examples, such as the Washington, Alaska, Montana, and Idaho program in the US, 6 the early community-oriented training experiences of Finnish medical schools, 7 and the heavily community-based curriculum of Canal Suez University in rural Egypt. 8 In fact, community “immersion learning has emerged as a strategy that addresses both educational and societal needs”, according to Zink et al. 9

The community-based learning approach has been further strengthened by the World Health Organization, which defines the social accountability of medical schools as “the obligation to direct education, research and service activities towards addressing priority health concerns of the community”. 10 Demonstrating social accountability in medical education calls for increasing student awareness of community health in its complexity. 11

From both a public health perspective and an educational perspective, immersion of medical students in the community seems a relevant way to raise awareness of future physicians of the health needs of the community and of the psychosocial dimensions of any health problem. 12 Indeed, sending medical students out into the community has been reported to have a positive impact on their future community engagement, giving them the opportunity of an early experience. 13 , 14

With the initiation of a new six-year integrated problem-based undergraduate medical curriculum in 1996, an interdisciplinary longitudinal community health program was introduced and progressively implemented at the Medical School in Geneva. 15 , 16 The objective of the paper is to describe the characteristics of one of the teaching activities of the community health program which has been its hallmark and met with remarkable success, ie, the community immersion clerkship, 17 as well as some community immersion clerkship evaluation data collected over a 15-year period and developments over the years.

Materials and methods

Time frame and study population.

The data reported corresponds to a 15-year observation period, ie, from spring 1997 to summer 2012. Over the 15-year period, we studied third-year medical students (in their last preclinical year), varying in number between 65 and 140 students a year, joined since 2007 by a small number of nutrition students (5–18 per year) from the University of Applied Health Sciences, giving in total 1407 students.

On a yearly basis, 22–35 health professionals participated as tutors, guiding the students through their community immersion projects. Some of these were community-based professionals, and others were teachers at the University of Applied Health Sciences or from the Medical School. Also, on a yearly basis, 8–10 health professionals working in grassroots projects at the community level were invited to present their activities to students in seminars. Furthermore, over the years, students visited (and revisited) more than 100 different community health institutions.

Study design

The course objectives and educational modalities were defined according to various approaches, and several methods of consensus (such as directed brainstorming and visualized discussion) between teachers and public health professionals taking a public health course at the university 18 , 19 were adopted. A survey of public health competencies useful to the practitioner was also done, 20 as was a review of the literature. The implementation process was started within the context of a global curriculum reorganization, adopting problem-based learning and bedside learning as the main educational strategies. 21

A global evaluation process was adopted for the program. The students’ perception of the program was monitored using a closed-response questionnaire on a five-point scale (1, very dissatisfied; 5, very satisfied). The questionnaire included items such as potential interest in investigating a health problem in its complexity, the potential enrichment in meeting with community health practitioners, and the potential positive experience of writing a report on the overall organization of the program. The students’ perception of the program was also monitored by yearly open group discussion. Second, achievement of learning objectives was evaluated by the program directors and teaching staff, according to a global grid integrating recommendations from educators, 22 a written report (on average 50 pages), an oral presentation of the group work to fellow students (30-minute presentation followed by a 10-minute question session), a poster presentation either on the community health network in charge of the investigated problem or on a specific aspect of the problem, as well as by a self-evaluation questionnaire administered to a selected cohort of students. Further, specific outcomes were monitored by the program coordinators over the years.

Program development

The 4–6-week community immersion clerkship is given at the end of the third preclinical year. Students in groups of 3-5 investigate and report on a priority health problem either in Geneva or in another country which their group has collectively selected and which has been accepted by the program coordinating staff. As a team, the students investigate their selected health problem by getting directly in touch, interviewing, and interacting with various community health institutions or community actors dealing with the problem at large (politicians, opinion leaders, associations, nongovernmental organizations), as well as meeting with concerned patients and families. Eventually, the students have to report on their investigation and findings in front of their peers. Each group of students has a tutor, usually a medical doctor or a social scientist with a public health background.

The community immersion clerkship is part of a larger community health program spanning the 6 years of undergraduate medical training, including community-oriented (epidemiology, occupational health, health economics, and ethics) as well as community-based training activities (such as ambulatory care clerkship, home care visits, and short-term clerkships in “low threshold” community health structures for vulnerable populations). 15 , 16

Definition of learning objectives

The main learning objectives were defined by consensus meetings between teaching staff and community health workers. These professionals came to the conclusion that, at the end of their community immersion clerkship, students should be able to:

- select and plan as a team an investigation in a community setting on a health problem in order to understand the problem in its biopsychosocial complexity

- collect the pertinent public health data and reflect upon them

- collaborate with the network of health institutions and professionals

- produce a written and oral report of the experiences and the health problem investigated.

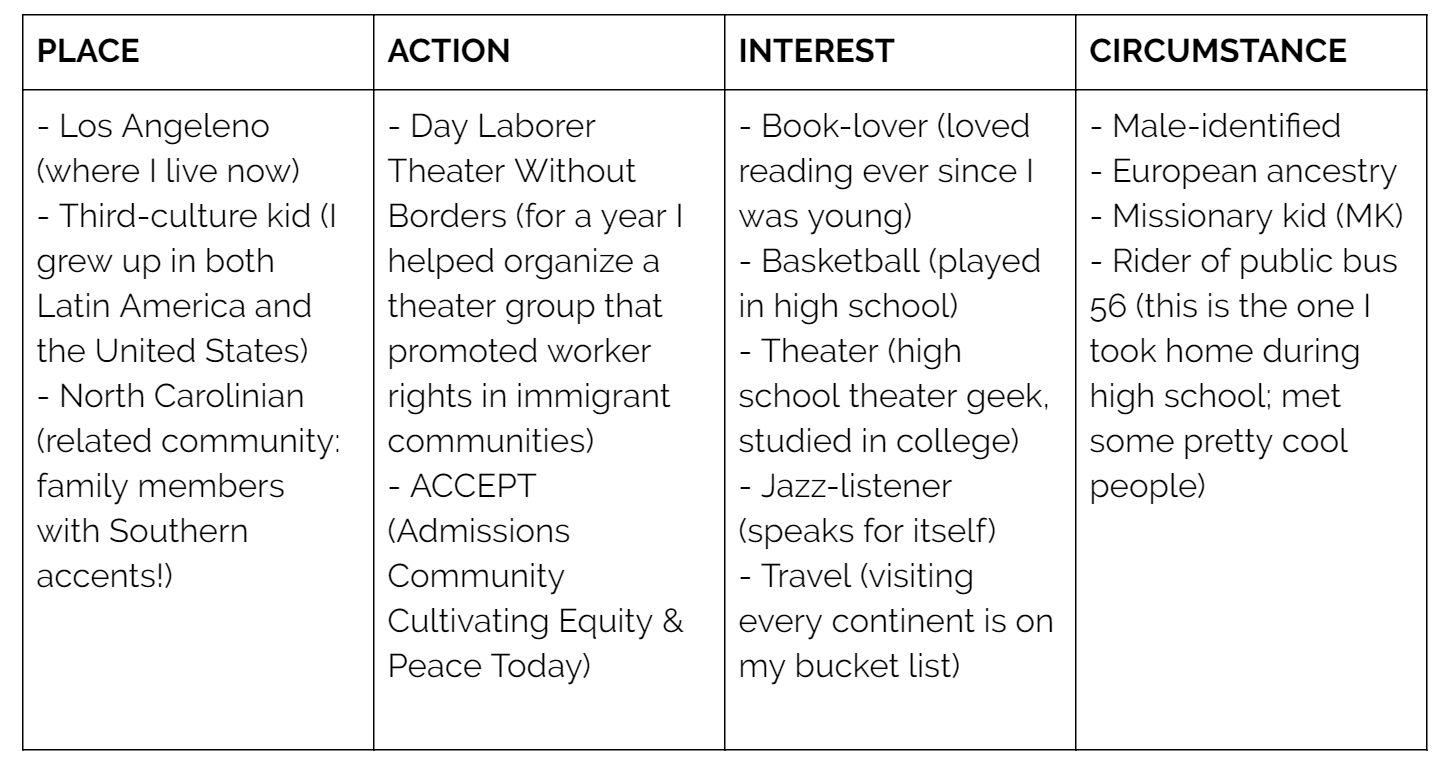

More specific learning objectives that were adopted are summarized in Table 1 . These include classical public health competencies as well as communication competencies and knowledge of basic human rights.

Specific learning objectives of the community immersion clerkship

| At the end of the community immersion clerkship students should be able to |

| – Describe a health problem in its biopsychosocial and cultural dimensions |

| – Establish the degree of priority of a health problem |

| – Describe the social and economic health risk related to a health problem |

| – Describe the functioning of the health services in relation to a given health problem |

| Furthermore, students should be able to |

| – Identify the community health network and the way health practitioners interact |

| – Analyze the role of general practitioners in handling a health problem in its biopsychosocial dimensions |

| – Identify the inequalities in access to health care of various subpopulations |

| – Identify the impact of social inequalities on the health of the individual and the community and to consider it in a human rights perspective |

| Eventually, by the end of the community immersion clerkship students will have |

| – Worked in a team |

| – Collected and analyzed health data |

| – Interacted with community health workers and the community at large |

| – Written a report on the health problem investigated |

| – Given an oral presentation on the health problem investigated in front of their peers and a poster presentation on the health network related to the health problem |

Definition of educational approach

Consensus was reached between teaching staff and the educational experts of the Unit of Development and Research in Medical Education at the Medical School and the Bachelor (preclinical) Program Committee that the students should:

- be put into an active learning situation, with the assignment being to investigate a given health topic by going into the community, write a report, and give a lecture on their community experience to their peers

- interact with community health workers and community health institutions in order to discover the community health network

- be given some autonomy in their investigation of a health problem and have the opportunity to choose their field of investigation and their team in order to keep motivation alive

- write a report.

Data evaluation

Evaluation of perception: student satisfaction.

Satisfaction, as monitored by a self-administered evaluation questionnaire in successive cohorts of students was high, with a mean global value of 4.4 and a mean participation rate over the years of 74%. More specifically, students ranked high the fact that community immersion clerkship allowed them to interact with community health practitioners (mean 4.6) and gave them the opportunity to investigate a health problem in its complexity (mean 4.5). Further, they appreciated the opportunity given to make an oral presentation of their work in front of their peers (mean 4.6). Less positively considered were the obligation to write a report (mean 3.7) and the amount of work that was expected (mean 3.8). Through the yearly brainstorming sessions organized (using the SWOT technique), 23 students’ perception of the highlights and pitfalls of the program showed consistency over time ( Table 2 ), and the taste of liberty (getting away from books) and discovery of the community, patients, families, and health professionals were much appreciated. Less enthusiasm was shown for writing the report or attending seminars.

Strengths and weaknesses of the community immersion clerkship according to students over the years (aggregated data)

| Hands-on experience outside of medical school Interacting with community health practitioners, patients, and families Investigating a health problem in its complexity | Time constraints Access to health professionals can be difficult Team work and group dynamics can be deleterious |

| Discovering social and cultural dimensions of health | |

| Choosing the problem freely | |

| Constituting the team freely | |

| Giving a lecture to peers | |

| Developing a community health network Discovering the role of different health professionals in handling a health problem and their complementarity | The paradox: the clerkship initially looks like a vacation and then becomes hard work Keeping up motivation in the long term |

| Taking the clerkship in a developing country | Tutorship can at times be a barrier to creativity |

Evaluation of learning: student performance

Acquisition of learning objectives, as measured by the quality of the written report, oral presentation, and poster presentation was good to very good for over 85% of students as evaluated by the program directors and teaching staff. When students were asked to self-evaluate the acquisition of competencies during their community immersion clerkship, it appeared that a large majority felt that they had acquired those competencies well ( Table 3 , data from two successive cohorts comprising 169 students).

Percentages of students who self-reported being able to perform specific clerkship-related competencies 9 months before the clerkship and one month, one year, 2 years, and 3 years afterwards

| Competencies related to community immersion clerkship | n = 121 9 months before % | n = 152 1 month after % | n = 98 1 year after % | n = 72 2 years after % | n = 68 3 years after % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Investigate a health problem from a biopsychosocial perspective | 32 | 92 | 90 | 90 | 90 |

| Establish the degree of priority of a health problem in a community | 21 | 76 | 80 | 94 | 90 |

| Collect data on a priority health problem in the community | 29 | 94 | 94 | 94 | 87 |

| Describe organization and functioning of community health services | 12 | 74 | 71 | 76 | 80 |

| Describe inequities in access to health services | 25 | 76 | 80 | 76 | 82 |

| Describe socioeconomic health risk factors | 18 | 86 | 85 | 78 | 78 |

| Identify community health actors | 24 | 92 | 88 | 85 | 86 |

| Describe collaboration channels between community health practitioners | 15 | 82 | 78 | 88 | 87 |

Behavior evaluation

Behavior evaluation could not be monitored per se. However, testimonies by former students indicate that the community immersion clerkship experience was a crucial one in their preclinical years. A few examples reported elsewhere 17 are given here as an illustration:

- “Never again shall we consider a mentally retarded child with the same eyes”, from a group who worked with children living with a handicap in Geneva

- “This experience helped us to understand that as medical doctors we are expected to play a role in the political debate”, from a group who worked on alternative medicines and their reimbursement by social security

- “We were ambivalent: was it good enough to treat the victim (wife) or go after the aggressor (husband)”, from a group who worked on honor crimes in India

- “It was a matter of a couple of packs of antibiotics and the mother would have survived: it was terribly hard to accept”, from a group who worked on mother and child health in Burkina Faso.

Impact evaluation

Educational innovations.

In the context of Geneva, the community immersion clerkship was innovative in introducing community-based activities and allowing the students to experience the hands-on approach of getting involved with community health institutions. It was also innovative in integrating community health workers into the teaching staff. Furthermore, it introduced innovative evaluation procedures, because it abandoned traditional multichoice questions in favor of a written report on the health topic investigated an oral presentation to fellow students, and a poster presentation on the community health network in charge of the health problem investigated. Some of these innovations even had some influence on several other programs of the curriculum, especially elective programs where several courses adopted written reports or oral presentations in front of colleagues as examination procedures.

Curriculum adaptations

Two major innovations took place over the years. The first was the development of collaboration with the University of Applied Health Sciences in charge of training nurses, dieticians, midwives, physiotherapists, and medical radiology technicians. This allowed creation of multiprofessional groups of students, similar to the teams of health professionals they would have to work with in the future. This experience, now in its seventh year, appears to be positive, with students as well as tutors having identified the complementary vision such an approach brings in studying a health problem in its biopsychosocial dimensions. Second, there was the possibility 10 years ago to take a clerkship, which was initially limited at Geneva, in a community health setting abroad. This triggered extraordinary interest among the students, who over the years came up with interesting community health projects around the world. Students must submit a community health project, which might be accepted or not by an ad hoc committee, and the project must also get support from a local community health structure that is in close connection with a Swiss-based association. Over the years, students have investigated health problems and become acquainted with different health systems with different social and cultural contexts in over 35 countries. Student feedback continues to be very positive, eg, “a unique experience, very enriching, that brings you to consider the world differently and that triggers a very personal journey on one’s role as a health professional and a world citizen”. Examples of topics investigated abroad and also in Geneva are listed in Table 4 .

Community immersion program: examples of topics studied over the years in Geneva and abroad

| Specific topics studied in Geneva | Domains of investigation | Specific topics studied in foreign countries |

|---|---|---|

| Measles | Infectious diseases | Malaria in Kenya |

| AIDS | Tuberculosis in Nepal | |

| STD | AIDS prevention in Gabon Chagas disease in Argentina AIDS in Bolivia Nosocomial infections in Mali | |

| Alcohol consumption | Behaviors/lifestyle | Violence against women in India |

| Addiction to illicit drugs | Addiction to illicit drugs in India | |

| Smoking | ||

| Violence against women | ||

| Diabetes | Chronic diseases | Diabetes in rural Benin |

| Obesity | Blindness in Nicaragua | |

| Coronary heart disease | Epilepsy in Equator | |

| Depression | Leprosy in Nepal | |

| Dementia | ||

| Paraplegia | ||

| Breast cancer | ||

| Lung cancer | ||

| Organization of medical emergencies | Organization of the health system | Access to safe birth in Nicaragua |

| Organ transplantation | Access to retroviral therapy in South Africa | |

| Palliative care versus euthanasia | Expanded program of immunization in Senegal | |

| Reimbursement of alternative/complementary medicines | Prevention of nosocomial infections in Armenia | |

| Activity of general practitioners in rural and urban areas | Access to health care in the Philippines | |

| Premature infants | Maternal and child health | Infant malnutrition in Burkina Faso |

| Pregnancies at risk | Children living with HIV in Thailand | |

| Abortion | Children living with a handicap in Peru | |

| Infertility | ||

| Children living with a handicap | ||

| Cystic fibrosis Autism | Congenital disorders | Children with congenital mental retardation in Vietnam |

| Trisomy | ||

| Health of detainees | Health of vulnerable populations | Health of street children in Mongolia |

| Health of sex workers | Health of street children in Argentina | |

| Health of refugees | Health of refugees in Lebanon | |

| Health of clandestine workers | Health of native populations in Australia |

Abbreviations: AIDS, acquired immune deficiency syndrome; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; STD, sexually transmitted infection.

Interactions between students and the community

Over the 15-year period of observation, while investigating their specific public health problems, students visited several hundred community health structures, local nongovernmental organizations, and international organizations. They also met and interviewed hundreds of patients and their families, as well as community health personnel and political decision-makers.

Students who took their clerkship in Geneva also organized specific events related to the health topic they were investigating, such as intra-university prevention campaigns against melanoma, promotion of vaccination against hepatitis B, and developing guidelines for prevention of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome among migrant populations. On several occasions, the students’ work had a direct influence on decisions made by health authorities, including:

- having investigated the health situation in “radical” squats, they organized “in-betweens”, ie, meetings between the squatters and the state health authorities who had “somewhat lost control of the situation”, a consequence of these meetings was the improvement of hygiene in the squats

- having worked on alternative and complementary medicines, the students helped to convince the ministry of health to reconsider reimbursement of these medicines by social insurance

- quite often (at least several times a year), community health professionals and institutions informed the course organizers that: they were grateful to the medical school for allowing its students to visit their community health institutions and to explore the health problem they were in charge of in its complexity, including its social dimensions; the students also regularly brought a new perspective to the investigated problem, in part due to their “innocence”, which allowed the professionals to reconsider some of their “established attitudes”.

Students who took their clerkship abroad were often able to support local community health centers in a very concrete way, such as teaching diabetic patients at a suburban health center in Ecuador, monitoring neonatal complications in a mother and child health center in Nicaragua, teaching basic hygiene (how to brush teeth and wash hands) to children in an orphanage in Vietnam, monitoring nosocomial infections in a community hospital in Mali, and developing a website and a brand for a small nongovernmental organization in Bolivia.

High student satisfaction rates and sustained student enthusiasm, strong faculty commitment, university support, and good acceptance by community health actors have allowed the community immersion clerkship program to become a highlight of the Geneva problem-based medical curriculum over the past 15 years. The community immersion clerkship program has also strengthened ties between community health institutions and the Medical School, contributing to the latter’s social accountability, as discussed in the literature. 24

The Geneva community immersion clerkship program was conceived of taking into account the community-based education recommendations defined by the World Health Organization 25 , 26 and later developed by Kristina et al, 27 including competencies in prevention and health promotion, identifying factors impacting on health, determining the incidence and prevalence of disease in the community, and collaborating with professionals from other disciplines. A special focus of the Geneva community immersion clerkship has been to facilitate students in encountering patients and health professionals in their own environment and confronting them with “the complex interplay between physical, psychological, social and environmental factors in health and illness”. 27

As mentioned elsewhere in the literature, 28 the consensus approach adopted by teachers and partner institutions in developing the program and defining its objectives seemed to facilitate implementation of the program and contribute to tutors’ commitment. It probably also strengthened the interaction between the students and community health institutions, thus providing facilitated learning opportunities, as has been reported already. 29

The evaluation results overall show student high satisfaction with the community immersion clerkship. In fact, the clerkship gets its highest approval ratings in the Geneva undergraduate medical curriculum, 16 with community-based medical programs being frequently evaluated well by students. 30 Students mentioned in particular their interactions with community health professionals, and patients and families as being fulfilling, enriching, and stimulating, which has also been mentioned by others. 31

Globally, the quality of the students’ work, in the form of written reports, oral presentations, and poster presentations, met the teachers’ expectations and university standards, in part due to the enthusiasm and commitment of students in their community involvement, which has been reported elsewhere. 31 Further, the students’ perception of their competencies seemed to be maintained over the years. Subjective self-reported perception of acquired competencies and high satisfaction with the community experience might stimulate motivation for learning 32 and orient future medical activities, contributing to the “training of community-responsive physicians”. 33

Although there was no true behavior evaluation, strong testimonies from students regarding their community experience suggest that this early hands-on experience in community settings might represent an important formative process and contribute to development of appropriate attitudes towards their future medical practice. 34 , 35

The community immersion clerkship program was quite innovative in its educational approach, at least when compared with local standards, given that it is a unique community immersion experience during the whole curriculum and fosters critical thinking and creativity among students.

There were two major adaptations made to the community immersion clerkship over the years, much in accordance with international recommendations. 36 First, a “formal partnership” with the University of Applied Health Sciences in charge of training nurses, physiotherapists, midwives, dieticians, and medical radiology technicians was established with the Medical School, which allowed collaborative projects between students, thus mixing students of different professional orientations and preparing them for future multiprofessional teamwork in the health sector, which has been advocated in the past. 37 Indeed, students showing prior experience with interprofessional education have been demonstrated to report significantly more positive attitudes towards multidisciplinary teamwork. 38 Second, the option to take the community immersion clerkship abroad fostered much energy and enthusiasm among students. It also gave students the opportunity for intercultural exposure and confronted them with health care at primary health care levels as well as with health issues when resources are scarce; such intercultural experiences might be especially valuable in the long term for medical practitioners in an ever-changing patient population. 39

The Geneva community immersion clerkship allowed students to interact with community health professionals, patients and their families, and community health decision-makers, such as politicians, legislators, and leaders, as well as community and nongovernmental organization leaders, thus preparing them to consider themselves as part of a network and as team members charged with the health of both individuals and communities, as recommended. The community immersion clerkship program also allowed hands-on experience with the implementation of real community health projects with the potential to contribute to the health of communities, and has certainly helped students to understand the concepts of public health. 40

The community immersion clerkship aims to train future doctors to respond to the health problems of individuals in all their complexity and to strengthen their ability to work with the community in order to promote healthy lifestyles and adequate health services, as well as raising their awareness of the necessity to collaborate with other health professionals. So far, the experience has been positive and the early enthusiasm of students has survived over the years. In the future, the program will need to move forward and seek more community involvement of students, encouraging them to make a commitment to and take leadership of community health projects, especially ones targeting vulnerable subgroups of the population, and thus drawing the Medical School towards more community involvement and more social accountability and responsibility.

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

- Our Mission

- Community Support

- Grants In Action

- Application Process

- Common Grant Login

- FAQ’s

- Board Member Resources

The Impact of Immersion

The Immersion Program at Rollins College is rooted in community engagement and leadership, seeking to broaden students’ understanding of the world through exposure to new environments and hands-on learning experiences.

“Ninety to ninety-five percent of immersion participants either agree or strongly agree that immersion experiences have an impact on them—to say it is powerful would be an understatement,” said Meredith Hein, director of the Center for Leadership and Community Engagement (CLCE) at Rollins College. “I truly believe it’s a life-changing experience for our students.”

The Immersion Program exists to offer student-led alternative break trips throughout Florida and other areas of the country. These trips, referred to as immersions, may last for a weekend or for a whole week, and are led by two student facilitators and one staff or faculty member. Each experience generally has between ten and twenty participants and focuses on a social impact area such as hunger, homelessness, the environment, or disaster relief, among many others. Immersion facilitators emphasize experiential learning and reflection on these trips, encouraging participants to consider how the issues they’re learning about affect their everyday lives.

The Immersion Program has been a part of Rollins since 2007, though it has experienced its most significant growth within the past three years. Meredith credits much of the Immersion Program’s recent success to the generous giving of the Miller Foundation.

“I don’t know that the Immersion Program would even exist [without funding from the Miller Foundation],” she said. “The Immersion Program is such a significant part of our work at Rollins. When you have a donor that supports something that is at the core of your mission, you can take a deep sigh of relief—you can sleep at night.”

Unprecedented Growth

Demand for immersion experiences has soared at Rollins in the last few years, to the point that CLCE has begun offering weekend experiences as well as week-long experiences. Each school year, more than 300 students, faculty, and staff members participate in twenty to twenty-five immersion experiences. As a result, Rollins has been ranked No. 1 for the highest percentage of students who participate in alternative break trips for three years in a row by Break Away, a national nonprofit organization that promotes quality alternative breaks.

Raul Carril (’15), a Rollins alumni and current graduate assistant with CLCE, remembers how the number of immersion applicants almost doubled in 2013-2014, the year he served as the student coordinator for the program. Raul believes that strengthening the Immersion Program brand—known as “Immersion Blue”—sparked new interest in the program that year by giving students something to gravitate toward visually.

“What are these immersion things?” students would ask when they saw their friends wearing their Immersion Blue T-shirts or painting their fingernails blue in anticipation of the reveal of new immersion destinations.