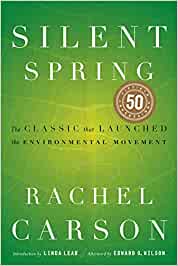

Book review: Silent Spring – Rachel Carson (1962)

Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring is as groundbreaking, controversial and relevant today as it was when it was first published in 1962.

The book argues that uncontrolled and unexamined pesticide use harms and even kills not only animals and birds, but also humans. Carson documents the detrimental effects of pesticides on the environment.

The text includes strong accusations against the chemical industry and a call to look at how the use of chemicals can cause damage and impact the world around us. Carson successfully demonstrates the fragility of the biodiversity on the planet and emphasises how chemical use can have a large repercussions.

Silent Spring has been credited with launching the contemporary American environmental movement. It has been widely read and pointed out concerns around the use of pesticides and the pollution of the environment.

Since publication, Silent Spring has created a debate among critics and supporters bringing the issues discussed to the forefront and allowing people to get involved and gain additional insight. Whilst parts of the book are now outdated, science has expand on the thesis and research in Silent Spring allowing readers to broaden their knowledge.

It was originally published as a series of articles and as a result seems a little disjointed at times, with some sections being isolated.

However, the fundamental point is that Silent Spring is a well written and inspiring call to action, and deserves its status as one of the seminal texts of the environmental movement.

You may like

Book Review: Ubernomics

Book Review: Business as an Instrument for Societal Change

Book Review: The Future MBA

Book Review: Eden 2.0 by Alex Evans

Book review: Collapse – Jared Diamond (2011)

Film review: Blind Spot (2008)

Like our Facebook Page

Savvy Investors Are Creating Eco-Friendly Portfolios

Potash: A Future Where Profitability Meets Sustainability

What Are the Most Eco-Friendly Flooring Materials?

Key Technologies For Sustainable Battlefield Strategies

10 Tips to Have a Low-Waste, Eco-Friendly Wedding

Study: Remote Work Lowers Carbon Footprint Up To 54%

India Boosts Its Solar Industry to Thwart Climate Change

Transportation Industry Goes Green With New Equipment

How To Find Sustainable Packaging For Your Move

How Environmental Injury Lawsuits Can Save the Planet

How to Become an Environmentally Conscious Entrepreneur in 2024

5 Reasons That Diamonds Can Be Excellent Green Investments

FoodTech Advances Can Feed the World Despite Climate Change

The Circular Economy is Conserving Biodiversity

- Submissions

- Newsletters

Silent Spring by Rachel Carson – Review

Silent Spring [1] is one of those books that many people may have heard of, even if they have not read it. Until about one month ago, this was true of me. It is an immensely powerful book, one that forms part of your personal experience in a way only a few books do.

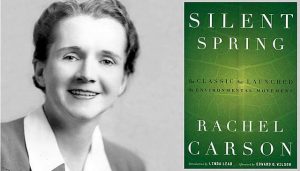

At home, she suffered challenges which led her to take full-time employment (analysing marine data with the Fisheries Bureau) so that she could support her widowed mother and her sister’s two orphaned daughters. She also wrote free-lance wildlife articles. In 1948 she gave up nearly all of her government work to concentrate on writing and independent research, proceeding to begin a three part ‘biography of the sea’ the first part of which was published by Oxford University Press [2] . Around the mid 1950s her main focus moved from the sea to conservation issues, especially the increasing use of manufactured pesticides. At home her responsibilities increased: in 1957 when her niece died prematurely, she adopted her five-year-old son, supporting him alongside her 88-year-old mother.

Rachel Carson was a rigorous scientist, and Silent Spring , though readable for the layperson, is packed full with verifiable research and data. In one chapter alone, she credits 42 sources for her information. This is significant, because she was well aware that her main conclusions were about as welcome to the chemical industry as a climate change campaigner at a Hummer show. Before publication she took the precaution of consulting other experienced scientists and medical researchers, fearing potential legal challenge unless she had her facts completely straight. This scientific rigour as well as widespread favourable public opinion [3] meant that attempts by representatives of the American chemical industry to gag and discredit her soon fizzled out.

Indeed, the book was almost immediately hugely influential. Despite having to cope with treatment for breast cancer and failing health, Carson did get to testify to President Kennedy’s Scientific Advisory Committee in 1963, and see some of her advice implemented through bans and restrictions on pesticide use (especially DDT).

What then, does Silent Spring tell us? Carson chose to introduce her book with an imagined scenario: the American countryside in a spring devoid of birds and other wildlife-hence silent. In the remaining sixteen chapters she explains how this possibility, in her view, was a distinct probability, unless action was taken to reduce the use of recent manufactured chemical pesticides and herbicides. To begin with, she explains the invention of the two main groups of industrial chemicals, chlorinated hydrocarbons (eg DDT) and those based on organic phosphorus (eg parathion). She argues that these products, largely invented for military purposes, got deployed after the end of the Second World War in a different war: against insect pests.

Carson provides us with details of this chemical war waged in the environment around her. Pests such as the fire ant and the spruce budworm were targeted (seemingly even when their threat was minor) and she catalogues the unintended consequences-polluted ground water; contaminated soil; death and disease in migrating salmon, water fowl, and songbirds (robins, in particular); and hedgerows decimated by herbicides.

Over increasingly large areas of the United States, spring now comes unheralded by the return of the birds and the early mornings are strangely silent where once they were filled with the beauty of bird song. The sudden silencing of the song of birds, this obliteration of the colour and beauty and interest they lend to our world have come about swiftly, insidiously and unnoticed by those whose communities are as yet unaffected. (95)

She includes too, an analysis of the toll taken on human health. She details cases of accidental exposure of workers to DDT as well as the known and/or suspected harm (including cancer) as a result of handling or eating plants or animals affected by chemical use. Primarily she questions the wisdom of introducing factory-made chemicals so fast and in such large quantities to the natural environment without testing their long-term effects. Specifically, she describes how the concentration of harmful chemical residues intensifies with each stage in the food chain. She also explains what biological resistance means and how an intended target pest could become resistant ( in the previous example of fire ants, a pesticide called haptachlor ended up virtually eradicating its predator, the corn borer):

…farmers have repeatedly traded one insect enemy for a worse one as spraying upsets the population dynamics of the insect world (234)

Along the way Carson gives us insight into her philosophy of living things, and especially the idea of balance in nature:

…a complex, precise and highly integrated system of relationships between living things which cannot safely be ignored any more than the law of gravity can be defied with impunity by a man perched on the edge of a cliff (226).

But above all she sets out to win both our minds and our hearts. I believe that she respected and felt committed, deep down, to the balance of nature, a commitment that developed out of her love of nature and her experience as a biologist. Continually she reminds us that to ignore nature and act as if humanity’s special role is to conquer it, can lead to very nasty surprises. So her ecological commitment was both moral and pragmatic; we should accept and honour the fact that we are part of the web of life, whilst to disregard that truth is irrational, as it may cause us serious harm.

Carson argues then that science and ethics go together. Those of us involved in sustainable farming or who adopt an ethical approach to the food, beauty care and other products they buy, or who work in animal welfare, human health, biodiversity and much more, all owe her a debt. No wonder Silent Spring had such a huge impact.

We can celebrate that Carson’s work led to the near-universal banning of DDT [4] and restraint in the use of other industrial chemicals. She reminded those of us that are farmers that there are benefits from abandoning the unnatural ‘monoculture’ model of agriculture for an approach that encompasses biodiversity. But two other questions she raised still hang uncomfortably over our ways of doing things.

First is the question of independent scientific research. In her own time Carson lamented the disparity between the huge budgets lavished on chemical -cide research and the modest sums allocated to biologists. She reminds us that most scientific research is dictated by commercial interests. And, in large part, bodies fund research that they consider will lead to financial gain; other potential research areas that could have led to huge benefit to human life, or the environment, go overlooked. Now, just as then, it is crucial to ask: is there a commercial objective that could be compromising research we read or hear about? Could there be a deliberate attempt to drown out any conflicting results?

Second is the question of public health. Her account of investigations to establish how human beings are affected by “chemical and physical agents that are not part of the biological experience of man” (171) gives the layperson an idea of what a complex area cause and effect is, in relation to health. And I’m not convinced that even our experts understand the full impact, at a genetic and cell level, of chemical pollution in our water, our air and maybe our food, through industrial and agri-business practices, food additives, medication…

But I’d like to end on a positive note. Carson’s efforts led to bans on chemical products known to injure human health and she put the issue of environmental pollution on the political agenda in democratic societies. [5] Her arguments in favour of biological control as a viable alternative to chemical spraying have led to widespread, safe and effective use of biological predators. (I really wish she was still around to tell us what she thought of GM.) Her guiding principles – a belief in ecology and ethical independent science- are her abiding legacy, and remain our best guides still in ongoing debates about the environment.

Silent Spring by Rachel Carson – Amazon

Photo Credits

Crop Duster photo by Ken Hammond

Rachel Carson portrait from her official US Fish and Wildlife Service employee photo taken in 1940.

[1] I used the fiftieth anniversary edition: Silent Spring Penguin Classics London 2012. This includes a foreword by Caroline Lucas.

[2] The Sea Around Us Oxford University Press 1951

[3] The book was serialised before being published in September 1962, principally in the popular New Yorker paper; it was chosen as book of the month just after publication, CBS Radio dramatised it, and reviewers praised it.

[4] DDT was banned in agricultural use in the US in 1972. Other countries followed suit (not until 1984 in the UK however!) It is still used against malaria, and there are vociferous supporters of its use for this purpose. However, research shows that mosquitoes build up resistance to DDT very quickly, and that community led approaches involving more than just DDT are most effective. In 2014 a UK study found higher levels of DDT residues in those suffering with Alzheimers.

[5] It is interesting also to note how many key issues she identified back when she wrote the book over fifty years ago. She raised the question of health and safety for consumers of garden chemicals (sold alongside foods in the supermarket), and the related question of misleading marketing (she felt that what were essentially poisons had a cosy, domesticated image in adverts and packaging). She set a benchmark for good research. She showed how politicians may invent crusades -at the end of the second world war the war on insects gave a plausible reason for putting decommissioned military planes back into service. She also touched on the issue of grass roots democracy when she described an environmental campaign by inhabitants of Maine.

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

| | |

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

SILENT SPRING

by Rachel Carson ‧ RELEASE DATE: Sept. 27, 1962

The book is not entirely negative; final chapters indicate roads of reversal, before it is too late!

It should come as no surprise that the gifted author of The Sea Around Us and its successors can take another branch of science—that phase of biology indicated by the term ecology—and bring it so sharply into focus that any intelligent layman can understand what she is talking about.

Understand, yes, and shudder, for she has drawn a living portrait of what is happening to this balance nature has decreed in the science of life—and what man is doing (and has done) to destroy it and create a science of death. Death to our birds, to fish, to wild creatures of the woods—and, to a degree as yet undetermined, to man himself. World War II hastened the program by releasing lethal chemicals for destruction of insects that threatened man’s health and comfort, vegetation that needed quick disposal. The war against insects had been under way before, but the methods were relatively harmless to other than the insects under attack; the products non-chemical, sometimes even introduction of other insects, enemies of the ones under attack. But with chemicals—increasingly stronger, more potent, more varied, more dangerous—new chain reactions have set in. And ironically, the insects are winning the war, setting up immunities, and re-emerging, their natural enemies destroyed. The peril does not stop here. Waters, even to the underground water tables, are contaminated; soils are poisoned. The birds consume the poisons in their insect and earthworm diet; the cattle, in their fodder; the fish, in the waters and the food those waters provide. And humans? They drink the milk, eat the vegetables, the fish, the poultry. There is enough evidence to point to the far-reaching effects; but this is only the beginning,—in cancer, in liver disorders, in radiation perils…This is the horrifying story. It needed to be told—and by a scientist with a rare gift of communication and an overwhelming sense of responsibility. Already the articles taken from the book for publication in The New Yorker are being widely discussed. Book-of-the-Month distribution in October will spread the message yet more widely.

Pub Date: Sept. 27, 1962

ISBN: 061825305X

Page Count: 378

Publisher: Houghton Mifflin

Review Posted Online: Oct. 28, 2011

Kirkus Reviews Issue: July 1, 1962

Share your opinion of this book

More by Rachel Carson

BOOK REVIEW

by Rachel Carson ; illustrated by Nikki McClure

by Rachel Carson

by Rachel Carson & Dorothy Freeman

More About This Book

APPRECIATIONS

WHY FISH DON'T EXIST

A story of loss, love, and the hidden order of life.

by Lulu Miller illustrated by Kate Samworth ‧ RELEASE DATE: April 14, 2020

A quirky wonder of a book.

A Peabody Award–winning NPR science reporter chronicles the life of a turn-of-the-century scientist and how her quest led to significant revelations about the meaning of order, chaos, and her own existence.

Miller began doing research on David Starr Jordan (1851-1931) to understand how he had managed to carry on after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake destroyed his work. A taxonomist who is credited with discovering “a full fifth of fish known to man in his day,” Jordan had amassed an unparalleled collection of ichthyological specimens. Gathering up all the fish he could save, Jordan sewed the nameplates that had been on the destroyed jars directly onto the fish. His perseverance intrigued the author, who also discusses the struggles she underwent after her affair with a woman ended a heterosexual relationship. Born into an upstate New York farm family, Jordan attended Cornell and then became an itinerant scholar and field researcher until he landed at Indiana University, where his first ichthyological collection was destroyed by lightning. In between this catastrophe and others involving family members’ deaths, he reconstructed his collection. Later, he was appointed as the founding president of Stanford, where he evolved into a Machiavellian figure who trampled on colleagues and sang the praises of eugenics. Miller concludes that Jordan displayed the characteristics of someone who relied on “positive illusions” to rebound from disaster and that his stand on eugenics came from a belief in “a divine hierarchy from bacteria to humans that point[ed]…toward better.” Considering recent research that negates biological hierarchies, the author then suggests that Jordan’s beloved taxonomic category—fish—does not exist. Part biography, part science report, and part meditation on how the chaos that caused Miller’s existential misery could also bring self-acceptance and a loving wife, this unique book is an ingenious celebration of diversity and the mysterious order that underlies all existence.

Pub Date: April 14, 2020

ISBN: 978-1-5011-6027-1

Page Count: 224

Publisher: Simon & Schuster

Review Posted Online: Jan. 1, 2020

Kirkus Reviews Issue: Feb. 1, 2020

GENERAL BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | NATURE | SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY

More by Lulu Miller

by Lulu Miller ; illustrated by Hui Skipp

THE BOOK OF EELS

Our enduring fascination with the most mysterious creature in the natural world.

by Patrik Svensson translated by Agnes Broomé ‧ RELEASE DATE: May 5, 2020

Unsentimental nature writing that sheds as much light on humans as on eels.

An account of the mysterious life of eels that also serves as a meditation on consciousness, faith, time, light and darkness, and life and death.

In addition to an intriguing natural history, Swedish journalist Svensson includes a highly personal account of his relationship with his father. The author alternates eel-focused chapters with those about his father, a man obsessed with fishing for this elusive creature. “I can’t recall us ever talking about anything other than eels and how to best catch them, down there by the stream,” he writes. “I can’t remember us speaking at all….Because we were in…a place whose nature was best enjoyed in silence.” Throughout, Svensson, whose beat is not biology but art and culture, fills his account with people: Aristotle, who thought eels emerged live from mud, “like a slithering, enigmatic miracle”; Freud, who as a teenage biologist spent months in Trieste, Italy, peering through a microscope searching vainly for eel testes; Johannes Schmidt, who for two decades tracked thousands of eels, looking for their breeding grounds. After recounting the details of the eel life cycle, the author turns to the eel in literature—e.g., in the Bible, Rachel Carson’s Under the Sea Wind , and Günter Grass’ The Tin Drum —and history. He notes that the Puritans would likely not have survived without eels, and he explores Sweden’s “eel coast” (what it once was and how it has changed), how eel fishing became embroiled in the Northern Irish conflict, and the importance of eel fishing to the Basque separatist movement. The apparent return to life of a dead eel leads Svensson to a consideration of faith and the inherent message of miracles. He warns that if we are to save this fascinating creature from extinction, we must continue to study it. His book is a highly readable place to begin learning.

Pub Date: May 5, 2020

ISBN: 978-0-06-296881-4

Page Count: 256

Publisher: Ecco/HarperCollins

Review Posted Online: Feb. 29, 2020

Kirkus Reviews Issue: March 15, 2020

NATURE | BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR | SURVIVORS & ADVENTURERS | GENERAL BIOGRAPHY & MEMOIR

- Discover Books Fiction Thriller & Suspense Mystery & Detective Romance Science Fiction & Fantasy Nonfiction Biography & Memoir Teens & Young Adult Children's

- News & Features Bestsellers Book Lists Profiles Perspectives Awards Seen & Heard Book to Screen Kirkus TV videos In the News

- Kirkus Prize Winners & Finalists About the Kirkus Prize Kirkus Prize Judges

- Magazine Current Issue All Issues Manage My Subscription Subscribe

- Writers’ Center Hire a Professional Book Editor Get Your Book Reviewed Advertise Your Book Launch a Pro Connect Author Page Learn About The Book Industry

- More Kirkus Diversity Collections Kirkus Pro Connect My Account/Login

- About Kirkus History Our Team Contest FAQ Press Center Info For Publishers

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Reprints, Permission & Excerpting Policy

© Copyright 2024 Kirkus Media LLC. All Rights Reserved.

Popular in this Genre

Hey there, book lover.

We’re glad you found a book that interests you!

Please select an existing bookshelf

Create a new bookshelf.

We can’t wait for you to join Kirkus!

Please sign up to continue.

It’s free and takes less than 10 seconds!

Already have an account? Log in.

Trouble signing in? Retrieve credentials.

Almost there!

- Industry Professional

Welcome Back!

Sign in using your Kirkus account

Contact us: 1-800-316-9361 or email [email protected].

Don’t fret. We’ll find you.

Magazine Subscribers ( How to Find Your Reader Number )

If You’ve Purchased Author Services

Don’t have an account yet? Sign Up.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Silent Spring by Rachel Carson – review

R achel Carson educated a planet: her book The Sea Around Us was a runaway bestseller from 1951, and I remember it affectionately as the beginning of my science instruction. You wouldn't consult it now: for her the planet was only 2.5bn years old and the moon was made of granite from the floor of what is now the Pacific Ocean, torn away from the molten, nascent Earth in some early tidal cataclysm.

At the time, exploration of the deep ocean had hardly begun. Scuba technology was in its infancy, the remotely operated submersible not even a fantasy. Space exploration was still a daydream; continental drift and sea-floor spreading a preposterous heresy. So her book was one of the goads that spurred on the next generation of oceanographers and marine biologists. In 1962, already dying of cancer, she published Silent Spring .

If you had to choose one text by one person as the cornerstone of the conservation movement, the signal for politically savvy environmental activism, and the beacon of worldwide lay awareness of ecological systems, Silent Spring would be most people's clear choice. Its impact was immediate, far-reaching and ultimately life-enhancing: it earned her a posthumous presidential medal and put her face on the 17 cent US postage stamp. It also earned her sustained vitriolic assault from the chemical industry and a claim from a former US Secretary of Agriculture that (because she was unmarried) she was "probably a communist": this, in a McCarthyite world, was almost the ultimate in character assassination.

But how does it read now?

It is brilliantly written: clear, controlled and authoritative; with confident poetical flourishes that suddenly illuminate pages of cool exposition. The pesticide residues in US drainage systems are unexpectedly counterpointed with "the sight and sound of drifting ribbons of waterfowl across an evening sky." Soil bacteria and fungi become a "horde of minute but ceaselessly toiling creatures".

Analysis of the incidental damage attendant upon agribusiness spraying gives way to an impassioned question: "Who has placed in one pan of the scales the leaves that might have been eaten by insects, and in the other, the pitiful heaps of many-hued feathers, the lifeless remains of the birds that fell before the unselective bludgeon of insecticidal poison?"

Her use of imagery and emotion is almost perfectly judged. She keeps her anger under control and simply marshals the tragedy that requires no comment. "In Florida, two children found an empty bag and used it to repair a swing. Shortly thereafter both of them died and three of their playmates became ill. The bag had once contained an insecticide called parathion, one of the organic phosphates; tests established death by parathion poisoning."

Most of the time, she lets the information do the work, and confines her poetic urges to chapter headings and the odd, throwaway conclusion. The book is a study in how to put an argument and win it.

It was, in its time, and to some extent is still, a terrific teaching text. It must have been one of the first truly popular books to introduce the ideas of the food chain, and of the amplification of enduring chemical residues; of ecological interdependence and the web of life on Earth; of the intricate workings of the cell and the potential for catastrophic intrusion at the level of the molecule; of the balance of predator-prey relationships and the folly of blundering interference.

It is also – although this can hardly have been what she intended – a brilliant critique of free-market capitalism, in which chemical companies concerned only with the balance sheet could persuade government and big business to dust and spray the US mainland with costly, persistent and highly toxic products that bore minimal, and sometimes barely visible, warnings of risk to health; in which research into the consequences of chemical overkill was barely funded, if at all; and in which alternative approaches – among them, biological control – were dismissed because nobody (except perhaps the misinformed farmer and the trusting consumer) would profit from them.

Finally, of course, it must be on its own terms one of the most effective books ever written. Many of the organochlorines and organophosphates at the heart of her story are now banned, difficult to find or used only under tightly controlled circumstances; there are now networks of amateur and professional naturalists monitoring the state of the wild things in every developed country; trout and salmon have returned to once devastated rivers; there are vociferous citizens' groups and environmental awareness campaigners; industry in the rich world has been held to account and forced to clean up its act; and most governments have environmental legislation and inspectorates.

There are now even voices that argue that the world overreacted , and that DDT – the most notorious of the sprays, although perhaps not the most dangerous - in its way, was a useful chemical under the right circumstances.

But – because it was so successful – Silent Spring can now be read without cold anger, fear or horror: three emotions that must have worked so powerfully for this success. The impact is, in all senses, stunning: someone now reading this chronicle of selected devastation (most of the evidence is from mainland America) is likely to feel dulled insensible by the repeated bludgeon blows of bleak observation, grim anecdote and sickening illustration.

In Rachel Carson's late fifties America, eggs grow cold in the nest, songbirds are silent, raptors lie dead in the meadows; fish float dead in their thousands downstream; roadside foliage turns brown and withers; cattle sicken; fruitpickers collapse with shock after a day in the orchards; physicians, householders, mothers and children fall mysteriously ill, experience partial paralysis, and slowly waste away.

Paradoxically, this was also the America of Walt Disney and Fred Astaire; of Norman Rockwell covers for the Saturday Evening Post; of homespun decency, rock'n'roll and the music of Aaron Copeland; of the Beat poets and the Kennedy campaign for the presidency and a new Camelot in Washington; a happy, confident place – although you might not know it from reading Silent Spring.

This was a profoundly important book. It remains an example of a very good book. It has earned a sure place in history and is a reminder that complacency is a dangerous state; that all human commerce has consequences that must be considered carefully; and that watchfulness is democracy's surest defence. It has been on my shelves for decades. But to be honest, although I began rereading with delight, I was relieved to get to the end of it: awful warnings have a way of making you feel awfully low-spirited.

Tim Radford 's geographical reflection, The Address Book: Our Place in the Scheme of Things is published by Fourth Estate

Next up: Starting on 7 November we will review all the shortlisted titles for the Royal Society Winton Prize for Science Books in the runup to the announcement of a winner on 17 November. There will be a Guardian competition to win all six shortlisted titles – details to follow.

The shortlist

Alex's Adventures in Numberland by Alex Bellos Through the Language Glass: How Words Colour Your World by Guy Deutscher The Disappearing Spoon by Sam Kean The Wavewatcher's Companion by Gavin Pretor-Pinney Massive: The Missing Particle That Sparked the Greatest Hunt in Science by Ian Sample The Rough Guide to the Future by Jon Turney

- Agriculture

- Science book club

- Science and nature books

- Conservation

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

Silent Spring is More than a Scientific Landmark: It’s Literature

On the underrated poetry of rachel carson's masterpiece.

“There was once a town in the heart of America where all life seemed to live in harmony with its surroundings.” This is the surprising first sentence of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring , the 1962 book that arguably sparked the modern environmental movement as we know it. Rachel Carson was a naturalist and science writer whose early work focused on oceanographic conservation. Her most famous book, however, details the harm wreaked on nature and humans by the rampant use of chemical pesticides. One of Silent Spring ’s lasting legacies is the grassroots environmental campaign that it stirred up, leading to, among other achievements, the phasing out of DDT in the United States in 1972.

While most people have heard of Silent Spring , even if they don’t consider themselves readers or environmentalists, many fewer have actually read it. Though it was a Book-of-the-Month pick in 1962 and serialized in The New Yorker that same year, the popular furor for the book has since died down, and it is now largely relegated to textbooks or other educational contexts.

That is why its first sentence is so surprising: Silent Spring does not read like a textbook. It begins with a fable and is filled with lyricism and passion throughout. Carson accomplished the feat of raising a public outcry against DDT not just with her research on its deleterious effects, but with the descriptive imagery, strong rhetoric, and poetic language that lift Silent Spring into the realm of other great works of American literature.

After the idyllic beginning of Carson’s fable, the fortunes of her American any-town take a dark turn. “Some evil spell had settled on the community,” she continues. “Everywhere was a shadow of death.” Animals are dying here, and so are humans. “It was a spring without voices,” she writes. “On the mornings that had once throbbed with the dawn chorus of robins, catbirds, doves, jays, wrens, and scores of other bird voices there was now no sound; only silence lay over the fields and woods and marsh.” She ends her introduction here: “What has already silenced the voices of spring in countless towns in America? This book is an attempt to explain.”

Though Carson’s use of this fable at first seems out of place in what is ostensibly a scientific treatise, it’s a literary device that effectively sums up not just Carson’s subject but her treatment of it as well. She paints such an evocative portrait of the natural world that the reader cannot help but sense the gravity of the environment’s presaged destruction. The fable signals that a plague of mythic proportions is afoot, but it’s real, and Carson’s book is an attempt to reveal its true nature.

The poetry of Carson’s opening continues into the rest of Silent Spring. There is lyrical language studded throughout the book; even Carson’s chapter titles—“Elixirs of Death,” “Earth’s Green Mantle,” “Through a Narrow Window”—are not what we might expect for a work of dense scientific research. But the places where Carson’s artistry is more apparent are in her chapter introductions. She weaves her most vivid images in the first few paragraphs of each chapter, creating a more tangible experience for the reader before transitioning into more complex scientific writing.

In the section entitled “Realms of Soil,” Carson conjures a geologic history practically in verse:

For soil is in part a creation of life, born of a marvelous interaction of life and nonlife long eons ago. The parent materials were gathered together as volcanoes poured them out in fiery streams, as waters running over the bare rocks of the continents wore away even the hardest granite, and as the chisels of frost and ice split and shattered the rocks. Then living things began to work their creative magic and little by little these inert materials became soil.

You almost forget that she’s talking about dirt.

After describing the earth’s potential losses at length, Carson pivots the narrative, showing nature in all its imperturbable force. In the beginning of the section entitled “Nature Fights Back,” Carson notes humanity’s futile efforts at controlling the landscape. She shifts into a series of examples with this light anaphora: “Then we sense something of the drama of the hunter and the hunted. Then we begin to feel something of that relentlessly pressing force by which nature controls her own.” These lines convey a sense of nature’s power from their structure as well as their meaning. The repeated beginnings, coupled with the strong final words—hunted, owned—propel these sentences forward into the coming descriptive passage.

What follows is two pages of exquisite imagery:

Here, above a pond, the dragonflies dart and the sun strikes fire from their wings. . . . Or there, almost invisible against a leaf, is the lacewing, with green gauze wings and golden eyes, shy and secretive, descendant of an ancient race that lived in Permian time. . . . Then this vital force is merely smoldering, awaiting the time to flare again into activity when spring awakens the insect world. Meanwhile, under the white blanket of snow, below the frost-hardened soil, in crevices in the bark of trees, and in sheltered caves, the parasites and the predators have found ways to tide themselves over the season of cold.

While she’s adept at translating the beauty of the natural world, the powerful emotions Carson elicits with this imagery are rarely rosy. Not only is Silent Spring a descriptive scientific work and a great work of literature—it is also an accusation. She uses the word “evil” 10 times, the word “sinister” six times, the word “suffer” 35 times, and permutations on the word death (including dead, deadly, die, died, and dying) a total of 213 times. The word “poison” alone appears 248 times. Given that my copy is just short of 300 pages, Carson’s meaning is hard to miss.

She calls the use of chemical herbicides and pesticides a “chemical war” in which “all life is caught in its violent crossfire.” Carson isn’t shy either about what she believes has led to this: “ . . . an era dominated by industry, in which the right to make a dollar at whatever cost is seldom challenged. When the public protests, confronted with some obvious evidence of damaging results of pesticide applications, it is fed little tranquilizing pills of half truth.”

“As man proceeds toward his announced goal of the conquest of nature, he has written a depressing record of destruction, directed not only against the earth he inhabits but against the life that shares it with him,” Carson writes, calling on her readers to question their part in this destructive past. “By acquiescing in an act that can cause such suffering to a living creature,” she asks, “who among us is not diminished as a human being?”

In all, Carson poses some 116 questions throughout Silent Spring , rhetorical questions that, taken as a sum, nonetheless call the reader to action.

Who has made the decision that sets in motion these chains of poisonings, this ever-widening wave of death that spreads out, like ripples when a pebble is dropped into a still pond? Who has placed in one pan of the scales the leaves that might have been eaten by the beetles and in the other the pitiful heaps of many-hued feathers, the lifeless remains of the birds that fell before the unselective bludgeon of insecticidal poisons? Who has decided—who has the right to decide— for the countless legions of people who were not consulted that the supreme value is a world without insects, even though it be also a sterile world ungraced by the curving wing of a bird in flight?

Who indeed? Reading this passage, elegantly comprised of Carson’s most effective rhetorical elements, it is difficult not to question the destructive decisions of those in power.

With a book full of passages like this, Carson gracefully cemented herself as both a pillar of modern American literature and a herald of the 20th century’s environmental movement. Her words are effective and convincing, and more so because they are beautiful. Silent Spring is clearly a tapestry patiently woven—with a cause worth fighting for.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Rebecca Renner

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Julie Buntin on Her Rebellious Youth and the Writing of Lorrie Moore

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

Review: ‘Silent Spring’ – Rachel Carson 1962

It’s not often you read a book that had as much impact on the world as Silent Spring. Carson’s direct and unambiguous criticism of pesticide use in America led to significant changes in public policy and was a key part of forming the modern day environmental movement.

Before Silent Spring most public dialogue about the environment was framed in terms of conservation. Habitats were to be preserved through initiatives like national parks, and endangered species nurtured in zoos. Carson’s narrative instead moved nature to the forefront of conversation, highlighting the ways in which in-discriminant pesticide use impacted not only the environment where conservation was or should be taking place, but also farms, suburban streets, backyards, communities and individual people.

One rather fascinating element of my edition was the Introduction by Lord Shackleton, presumably to help British readers understand that the problems outlined in America also applied to them. He is strongly supportive of Carson’s message, but most of all I enjoyed his rather paternal dig at dissenters that could equally be applied to climate change deniers in the modern day:

”I would ask those who find parts of this book not to their taste or consider that they can refute some of the arguments to see the picture as a whole. We are dealing with dangerous things and it may be too late to wait for positive evidence of danger.”

While Silent Spring is an important book I think reading an edition with a modern foreword or afterword is essential. My Penguin Modern Classics contains an afterword by Linda Lear written in 1998 which was helpful in putting Carson’s work into context – but a more recent interpretation would be preferable. I was interested, and saddened to hear that Carson’s gender was the basis on which much of her work was criticized. Some of the science Carson cites and conclusions she draws have over time been proved false. However the principle of her argument remains as relevant today as it was in the 1960’s when this book was first published.

It is certainly not going to be a book that I recommend widely – it is a rather niche area of interest. But it really is a book that changed the course of history, and a terrific example of how one voice (and a woman’s at that) filled with conviction and backed with evidence can tap into a significant issue and bring about change.

View all my reviews

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Currently you have JavaScript disabled. In order to post comments, please make sure JavaScript and Cookies are enabled, and reload the page. Click here for instructions on how to enable JavaScript in your browser.

- Engineering & Transportation

- Engineering

Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) is a service we offer sellers that lets them store their products in Amazon's fulfillment centers, and we directly pack, ship, and provide customer service for these products. Something we hope you'll especially enjoy: FBA items qualify for FREE Shipping and Amazon Prime.

If you're a seller, Fulfillment by Amazon can help you grow your business. Learn more about the program.

| This item cannot be shipped to your selected delivery location. Please choose a different delivery location. |

Sorry, there was a problem.

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the authors

Silent Spring Paperback – Unabridged, February 1, 2022

THE CLASSIC THAT LAUNCHED THE ENVIRONMENTAL MOVEMENT

“Rachel Carson is a pivotal figure of the twentieth century…people who thought one way before her essential 1962 book Silent Spring thought another way after it.”—Margaret Atwood

Rarely does a single book alter the course of history, but Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring did exactly that. The outcry that followed its publication in 1962 forced the banning of DDT and spurred revolutionary changes in the laws affecting our air, land, and water. Carson’s passionate concern for the future of our planet reverberated powerfully throughout the world. As Carson reminds us, "In nature, nothing exists alone.”

The introduction by the acclaimed biographer Linda Lear, author of Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature , tells the story of Carson’s courageous defense of her truths in the face of a ruthless assault form the chemical industry following the publication of Silent Spring and before her untimely death.

“Wonder and humility are just some of the gifts of Silent Spring. They remind us that we, like all other living creatures, are part of the vast ecosystems of the earth of the earth…this is a book to relish: not for the dark side of human nature, but for the promise of life’s possibility.” —from the Introduction

- Print length 400 pages

- Language English

- Lexile measure 1340L

- Dimensions 5.5 x 0.88 x 8.25 inches

- Publisher Mariner Books Classics

- Publication date February 1, 2022

- ISBN-10 0618249060

- ISBN-13 978-0618249060

- See all details

From the Publisher

| Customer Reviews | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Editorial Reviews

About the author, excerpt. © reprinted by permission. all rights reserved., product details.

- Publisher : Mariner Books Classics; Anniversary edition (February 1, 2022)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 400 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0618249060

- ISBN-13 : 978-0618249060

- Reading age : 15+ years, from customers

- Lexile measure : 1340L

- Item Weight : 1 pounds

- Dimensions : 5.5 x 0.88 x 8.25 inches

- #1 in Environmentalism

- #1 in Environmental Science (Books)

- #5 in Ecology (Books)

About the authors

Linda j. lear.

Linda Lear is an environmental historian and the author of two prize-winning biographies: Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature (2009) and Beatrix Potter: A Life in Nature (2007). She has written the introduction to the 50th anniversary edition of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring (2012) and edited an anthology of Carson's unpublished writing, Lost Woods: The Discovered Writing of Rachel Carson (1998). She maintains www.rachelcarson.org. Linda lives in Bethesda, Maryland and Charleston, South Carolina.

Rachel L. Carson

Rachel Carson (1907-1964) spent most of her professional life as a marine biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. By the late 1950s, she had written three lyrical, popular books about the sea, including the bestselling The Sea Around Us, and had become the most respected science writer in America. She completed Silent Spring against formidable personal odds, and with it shaped a powerful social movement that has altered the course of history.

Customer reviews

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 5 star 77% 14% 5% 2% 2% 77%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 4 star 77% 14% 5% 2% 2% 14%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 3 star 77% 14% 5% 2% 2% 5%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 2 star 77% 14% 5% 2% 2% 2%

- 5 star 4 star 3 star 2 star 1 star 1 star 77% 14% 5% 2% 2% 2%

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Customers say

Customers find the book insightful, poetically elegant, and critically accurate. They also say it's very thoroughly written and covers in great detail.

AI-generated from the text of customer reviews

Customers find the book insightful, epic, and compelling. They also say the opening chapter really grabs their attention. Customers also say it's a classic that remains very relevant. They say the book provides logical explanations of how all living things are dependent on each other.

"...It is an immensely powerful scientific book for general readers packed full of verifiable research and data...." Read more

"...It’s very good and gives a stark picture of what was going on at the time it was published. I enjoyed it very much." Read more

"...All in all, though, this book is readable, relevant , and worth a perusal before you go nuts with the Round-Up on the dandelions." Read more

"...This is definitely the book that will help open your mind to love ." Read more

Customers find the book very thoroughly written, detailed, and easy to understand. They also say the author is a great writer and could reach most educated people.

"...Carson writes all of this in strong, clear prose that first explains the concepts she's introducing and then illustrates them with examples of the..." Read more

"...Other than that, it’s light reading !" Read more

"...Her writing style is more than accessible , often poetically elegant as well as critically accurate and with minute detail in terms of her charges of..." Read more

"...It is not always easy for the reader to follow Carson's technical details...." Read more

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

How Rachel Carson’s ‘Silent Spring’ Awakened the World to Environmental Peril

By: Cate Lineberry

Updated: April 22, 2022 | Original: April 20, 2022

When Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring was published in September 1962, she was already a celebrated American biologist and author best known for her trilogy of lyrical books on the ocean. But rather than introducing readers to more of the natural world, the mild-mannered 55-year-old’s latest book warned they could be destroying it.

In what she referred to as her “poison book,” Carson revealed the damaging effects of the indiscriminate use of chemical pesticides on the environment. She focused mainly on the insecticide DDT, which had been dubbed “one of the greatest discoveries of World War II” by Time magazine for its ability to kill insects that spread malaria and typhus and was routinely sprayed in homes and on crops.

Carson called for much greater caution against these “elixirs of death” and wrote, “If we are living so intimately with chemicals—eating and drinking them, taking them into the very marrow of our bones—we had better know something about their power.”

Though the scientific community already knew of the dangers, Carson was the first to make the information accessible and palatable to a mass audience in her groundbreaking book. “She wrote for the general public, not the scientific community,” says Linda Lear, author of Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature. “Readers, including housewives who used a lot of these chemicals, were shocked with what they learned."

She argued “that people have a right to know what they're being exposed to and what risks are posed,” says William Souder, author of On a Farther Shore: The Life and Legacy of Rachel Carson . This was particularly relevant given that the book was published at the height of the Cold War. To help readers understand the dangers, Carson drew a parallel between pesticide contamination and fallout from the regular testing of nuclear weapons. “In framing these issues as siblings,” says Souder, “Carson helped the public to understand that pesticides could be harmful, even though you weren't aware of their presence, something that people already knew about radiation.”

'Silent Spring' Has Immediate Impact

The public’s first glimpse at Silent Spring had actually come in June 1962 when The New Yorker ran three excerpts. By the time it was published that fall, it was in such high demand that it became an instant bestseller. In the first three months, it sold more than 100,000 hardcover copies, and in two years, more than one million.

The book was quickly celebrated. Senator Ernest Gruening, a Democrat from Alaska, said, “Every once in a while in the history of mankind, a book has appeared which has substantially altered the course of history.” Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas and E.B White of the New Yorker both compared the impact of the book to Uncle Tom’s Cabin .

As expected, the reaction from the chemical companies was swift and severe. One industry spokesperson dismissed Carson’s claims as “absurd.” Others accused her of being a hysterical woman, a communist and a radical. The president of the company that made DDT said Carson wrote “not as a scientist, but as a fanatic defender of the cult of the balance of nature.”

The New York Times covered the industry’s reaction in a front-page article: “The $300,000,000 pesticides industry has been highly irritated by a quiet woman author whose previous works on science have been praised for the beauty and precision of the writing.”

Carson had resisted writing the book for years because of these anticipated attacks from the chemical companies as well as public officials who had accepted their false claims. “It was a David versus Goliath sort of saga,” says Lear. “ She was uncovering industrial misdeeds and, in the course of that, bringing down powerful men who had been entrusted by the public and shown to be unworthy of that trust.”

Fortunately, Carson decided the personal risks were worth it. But it came at great personal cost as she was fighting breast cancer throughout much of the four years in which she wrote Silent Spring . “In the end, she gave in to a sense of obligation,” says Souder. “She felt that she had no other choice but to tackle the subject herself.”

JFK Spotlights Carson's Book

Shortly after her book was published, President Kennedy was asked at a press conference if the government would look into the long-term effects of synthetic pesticides. He responded, “Yes, and I know they already are. I think, particularly, of course, since Miss Carson’s book.”

The following April, 15 million viewers tuned in to watch a CBS TV special, called “The Silent Spring of Rachel Carson.” Carson’s thoughtful responses and calm demeanor despite her failing health bolstered her arguments. She said, “It is the public that is being asked to assume the risks that the insect controllers calculate. The public must decide whether it wishes to continue on the present road, and it can do so only when in full possession of the facts.”

In May 1963, President Kennedy's Science Advisory Committee issued its long-awaited pesticide report, which validated Carson’s work. The committee’s scientists called for more research into potential health hazards related to pesticides and urged more restraint in their widespread use in homes and fields.

The CBS program combined with the findings of the presidential committee had solidified pesticides as a major public issue. Silent Spring had awakened a new environmental consciousness and set the stage for the establishment of the Environmental Protection Agency in 1970, which regulated use of pesticides, and the banning of DDT in 1972.

Carson died from breast cancer on April 14, 1964, less than two years after her seminal book was published but not before she changed the way Americans viewed their world. Says Souder, “Carson changed the conversation about the environment, recasting humankind as part of nature, not above it.”

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Silent Spring by Rachel Carson

The 65th greatest book of all time

- Comments (0)

If you're interested in seeing the ranking details on this book go here

This book is on the following 33 lists:

- 5th on The Modern Library | 100 Best Nonfiction (The Modern Library)

- 16th on 25 Greatest Science Books of All Time (Discover Magazine)

- 52nd on The Greatest Books of All Time (Reader's Digest)

- 78th on The 100 Best Non-Fiction Books of the Century (National Review)

- 87th on Koen Book Distributors Top 100 Books of the Past Century (themodernnovel.com)

- 320th on Our Users' Favorite Books of All Time (The Greatest Books Users)

- Books That Changed the World (Book)

- Best Books Ever (bookdepository.com)

- 48 Good Books (University of Buffalo)

- The 100 Best Nonfiction Books of All Time (The Guardian)

- The New York Public Library's Books of the Century (New York Public Library)

- 100 Major Works of Modern Creative Nonfiction (ThoughtCo)

- As if You Don't Have Enough to Read, Best Non-Fiction from the NY Times Writers (New York Times)

- 500 Great Books by Women (Book)

- The Booklist Century: 100 Books, 100 Years (BookList)

- The 50 Most Influential Books of All Time (Open Education Database)

- 100 All-Time Greatest Popular Science Books (Open Education Database)

- Daily Telegraph's 100 Books of the Century, 1900-1999 (Daily Telegraph)

- 1,000 Books to Read Before You Die: A Life-Changing List (1,000 Books to Read Before You Die(Book))

- 75 Books by Women Whose Words Have Changed the World (Women's National Book Association)

- 87 Books Written by Women That Are So Good, You Won't Be Able to Put Them Down (Pop Sugar)

- Books That Shaped America (Library of Congress)

- Twenty Books that Changed the World (The Guardian)

- 10 of the Best Popular Science Books as Chosen by Authors and Writers (NewScientist )

- The Well-Educated Mind (Book)

- The 100 Greatest Non-Fiction Books (The Guardian)

- 100 Best Non-Fiction Books of the 20th Century (and Beyond) in English (Counterpunch)

- Recommended Reading List for Students (China 2020) (Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China)

- The 75 Best Books of the Past 75 Years (Parade Magazine)

- 50 Greatest Books of All Time (Globe and Mail)

- 100 Most Influential Books of the Century (Boston Public Library)

- 100 Books to Read in a Lifetime (Amazon.com (USA))

- Books That Changed the World: The 50 Most Influential Books in Human History (Book)

Agriculture

Conservation, engineering, environment, nature & environment, physical sciences, public awareness, sports & outdoors, united states, create custom user list, purchase this book, edit profile.

- Get a Free Review of Your Book

- Enter our Book Award Contest

- Helpful Articles and Writing Services

- Are you a Publisher, Agent or Publicist?

- Five Star and Award Stickers

- Find a Great Book to Read

- Win 100+ Kindle Books

Get Free Books

- Are you a School, Library or Charity?

Become a Reviewer

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Partner

Award Winners

Non-fiction, book reviews.

- 2023 Award Winners

- 2022 Award Winners

- 2021 Award Winners

- 2020 Award Winners

- 2019 Award Winners

- 2018 Award Winners

- 2017 Award Winners

- 2016 Award Winners

- 2015 Award Winners

- 2014 Award Winners

- 2013 Award Winners

- 2012 Award Winners

- 2011 Award Winners

- 2010 Award Winners

- 2009 Award Winners

- Children - Action

- Children - Adventure

- Children - Animals

- Children - Audiobook

- Children - Christian

- Children - Coming of Age

- Children - Concept

- Children - Educational

- Children - Fable

- Children - Fantasy/Sci-Fi

- Children - General

- Children - Grade 4th-6th

- Children - Grade K-3rd

- Children - Mystery

- Children - Mythology/Fairy Tale

- Children - Non-Fiction

- Children - Picture Book

- Children - Preschool

- Children - Preteen

- Children - Religious Theme

- Children - Social Issues

Young Adult

- Young Adult - Action

- Young Adult - Adventure

- Young Adult - Coming of Age

- Young Adult - Fantasy - Epic

- Young Adult - Fantasy - General

- Young Adult - Fantasy - Urban

- Young Adult - General

- Young Adult - Horror

- Young Adult - Mystery

- Young Adult - Mythology/Fairy Tale

- Young Adult - Non-Fiction

- Young Adult - Paranormal

- Young Adult - Religious Theme

- Young Adult - Romance

- Young Adult - Sci-Fi

- Young Adult - Social Issues

- Young Adult - Thriller

- Christian - Amish

- Christian - Biblical Counseling

- Christian - Devotion/Study

- Christian - Fantasy/Sci-Fi

- Christian - Fiction

- Christian - General

- Christian - Historical Fiction

- Christian - Living

- Christian - Non-Fiction

- Christian - Romance - Contemporary

- Christian - Romance - General

- Christian - Romance - Historical

- Christian - Thriller

- Fiction - Action

- Fiction - Adventure

- Fiction - Animals

- Fiction - Anthology

- Fiction - Audiobook

- Fiction - Chick Lit

- Fiction - Crime

- Fiction - Cultural

- Fiction - Drama

- Fiction - Dystopia

- Fiction - Fantasy - Epic

- Fiction - Fantasy - General

- Fiction - Fantasy - Urban

- Fiction - General

- Fiction - Graphic Novel/Comic

- Fiction - Historical - Event/Era

- Fiction - Historical - Personage

- Fiction - Holiday

- Fiction - Horror

- Fiction - Humor/Comedy

- Fiction - Inspirational

- Fiction - Intrigue

- Fiction - LGBTQ

- Fiction - Literary

- Fiction - Magic/Wizardry

- Fiction - Military

- Fiction - Mystery - General

- Fiction - Mystery - Historical

- Fiction - Mystery - Legal

- Fiction - Mystery - Murder

- Fiction - Mystery - Sleuth

- Fiction - Mythology

- Fiction - New Adult

- Fiction - Paranormal

- Fiction - Realistic

- Fiction - Religious Theme

- Fiction - Science Fiction

- Fiction - Short Story/Novela

- Fiction - Social Issues

- Fiction - Southern

- Fiction - Sports

- Fiction - Supernatural

- Fiction - Suspense

- Fiction - Tall Tale

- Fiction - Thriller - Conspiracy

- Fiction - Thriller - Environmental

- Fiction - Thriller - Espionage

- Fiction - Thriller - General

- Fiction - Thriller - Legal

- Fiction - Thriller - Medical

- Fiction - Thriller - Political

- Fiction - Thriller - Psychological

- Fiction - Thriller - Terrorist

- Fiction - Time Travel

- Fiction - Urban

- Fiction - Visionary

- Fiction - Western

- Fiction - Womens

- Non-Fiction - Adventure

- Non-Fiction - Animals

- Non-Fiction - Anthology

- Non-Fiction - Art/Photography

- Non-Fiction - Audiobook

- Non-Fiction - Autobiography

- Non-Fiction - Biography

- Non-Fiction - Business/Finance

- Non-Fiction - Cooking/Food

- Non-Fiction - Cultural

- Non-Fiction - Drama

- Non-Fiction - Education

- Non-Fiction - Environment

- Non-Fiction - Genealogy

- Non-Fiction - General

- Non-Fiction - Gov/Politics

- Non-Fiction - Grief/Hardship

- Non-Fiction - Health - Fitness

- Non-Fiction - Health - Medical

- Non-Fiction - Historical

- Non-Fiction - Hobby

- Non-Fiction - Home/Crafts

- Non-Fiction - Humor/Comedy

- Non-Fiction - Inspirational

- Non-Fiction - LGBTQ

- Non-Fiction - Marketing

- Non-Fiction - Memoir

- Non-Fiction - Military

- Non-Fiction - Motivational

- Non-Fiction - Music/Entertainment

- Non-Fiction - New Age

- Non-Fiction - Occupational

- Non-Fiction - Parenting

- Non-Fiction - Relationships

- Non-Fiction - Religion/Philosophy

- Non-Fiction - Retirement

- Non-Fiction - Self Help

- Non-Fiction - Short Story/Novela

- Non-Fiction - Social Issues

- Non-Fiction - Spiritual/Supernatural

- Non-Fiction - Sports

- Non-Fiction - Travel

- Non-Fiction - True Crime

- Non-Fiction - Womens

- Non-Fiction - Writing/Publishing

- Romance - Comedy

- Romance - Contemporary

- Romance - Fantasy/Sci-Fi

- Romance - General

- Romance - Historical

- Romance - Paranormal

- Romance - Sizzle

- Romance - Suspense

- Poetry - General

- Poetry - Inspirational

- Poetry - Love/Romance

Our Featured Books

Hulight Visions

Pirates of Breakaway Bay

The Poppy Field

Sketches of Curious Events and Practices in the Lives of the Intriguing People Who Inhabited Early America

Invisible Wounds

Lubelia Alycea

Mojave Rock

Resurrection 2020

Status Quo Is Not Company Policy

Self-Inflicted

The Taxidermist

Boy, Kant You Read!

The Platinum Sword and the Kingdom of Reveal

Survive the Day

The Citadel

Total Control

Kindle book giveaway.

Silent Spring - Deadly Autumn of the Vietnam War

Click here to learn about the free offer(s) from this author..

Author Biography

Reviewed by Fiona Ingram for Readers' Favorite

For the rest of the world, the Vietnam War is over. For the soldiers who fought in it, no matter what their role, it will never be over. Silent Spring: Deadly Autumn of the Vietnam War is described by author and Vietnam veteran Patrick Hogan as “part memoir, part exposé, and part call to action against the bureaucratic and legislative negligence and indifference that has violated, and continues to violate, the trust of veterans and US citizens as a whole.” Succinct and well put, this is the perfect description of a horrific cover-up, one of the greatest crimes against humanity of the 20th century, and one that, had it happened today, would have been labelled genocide. The author served two years, nine months and 22 days in Vietnam and that was enough to poison his body to the extent that he ended up with a laundry list of ailments. These only manifested 43 years after his service ended, but confirmed Patrick’s conviction that his time in Vietnam and his numerous illnesses were linked. After all, on many occasions, among the reasons cited by medical experts for his problems were the two chilling words “environmental agents.” And thus began his exhaustive and minutely detailed investigation into the witches’ brew of potentially lethal tactical pesticides which he is sure contributed to the decline in his health and that of many other veterans. Sidelined and pushed from pillar to post, Patrick came up against the stone-walling tactics of the Department of Veterans Affairs (DVA) and the US government, both of which deny the effects of the toxic chemicals Vietnam veterans were exposed to during the war. The reasonable person wonders why the government and chemical companies did not set about covering medical bills and compensating these men. The answer is simple. Money and greed. The refusal of the DVA and the US administration to accept responsibility is to protect them from international liability and accusations of use of chemical warfare/weapons (which is the case) and to avoid the massive payouts they would be forced to make. This is a shameful indictment of the political administration of the time, and the current one, when reparations could but won’t be made. I had a vague idea of the Vietnam War when I picked up this book, and of course I had heard of the infamous Agent Orange, a horrifying and deadly herbicide and defoliant chemical used to destroy jungle cover for the enemy and any food supplies they might locate there. The US government destroyed millions of acres of South Vietnam jungles. It was an environmental catastrophe beyond any natural disaster ever known. I had never heard of Agent White and the numerous other toxic and deadly concoctions, a chemical poisonous soup, used as pesticides. Vietnam is home to myriad insects, bugs, and critters all carrying their own types of bites, stings and diseases. They had to be exterminated. The problem was that daily exposure to these poisons inevitably altered the molecular structure of the cells of people exposed, but took years, even decades, to manifest. This gave the government and the DVA enough wiggle room to claim inconclusive evidence and to fudge the facts and manipulate the statistics. Despite the mind-boggling details and chilling statistics contained in this memoir, the author has no moments of self-pity. He includes very detailed research, scientific, chemical and medical information, but all in a very readable, user-friendly style. I felt as if I were sitting with the author and chatting over coffee. He manages to intersperse facts and figures with events in a way that makes it easy to absorb the statistics and the information which is so relevant to his story. Photographs are an added bonus to help the reader visualize the location and the living conditions of the men who served in Vietnam. The facts are thoroughly researched with bibliographic and reference end notes to give credibility to Patrick Hogan’s story, one of tragedy shared by many, many other soldiers who gave their lives in a war that should never have been fought. Very impressive and highly recommended.

Viga Boland

As a reviewer, in the past few months I’ve had the opportunity to read several books, usually memoirs, penned by vets of the Vietnam War. Every one of them has been an enlightening and heart-wrenching read. Some of these vets have written graphic details of what they witnessed and endured while doing their “duty”. Others have focused on the battles they have continued to fight with PTSD after returning home. But Silent Spring: Deadly Autumn of the Vietnam War by Patrick Hogan is the first memoir I’ve read that zeroes in on the ongoing battles a countless number of these vets continue to fight even 40 years later: the killer battles with their health, and with the DVA, EPA and various US Health Departments to receive some kind of compensation after being, as Hogan calls it, “treacherously betrayed”. Patrick Hogan writes passionately, but for the most part, conversationally. We meet him initially through his own story of suffering, primarily with health issues that began almost immediately after returning from service, but for which doctors could find no specific cause. Now, decades later, with so many vital organ parts having been removed, coupled with endless rounds with heart trouble, COPD and so much more, Hogan has narrowed his critical health issues down to his exposure to Agents Orange and White and various other chemical pesticides and insecticides sprayed by the US on Vietnam crops and jungles. There can be no question that these sprays eventually made their way into the troops’ bodies via their own food and water, not to mention while showering under a chemical soup at the end of a day. To support his thesis, Hogan has extensively researched his subject, supplying pages of references at the end of the book. He includes copious lists of the chemicals in these sprays, and details their effects on all living organisms. This information makes readers shudder with disbelief and revulsion, especially in learning from documents Hogan supplies that though it is consistently denied, the US government was indeed aware of the possible dangers to life in using these chemicals. But at the same time, no extensive testing had been done ie. these vets were, in a sense, guinea pigs. So now, years later, vets are suffering and dying from a multitude of illnesses, similar in each of them. Hogan himself has, for too many years, been fighting the Veteran's Administration over service-connected disability issues. This struggle has finally secured him 80% service-connected disability. But what of all the others who have died fighting a battle they can’t win with their health? Hogan’s intention in writing Silent Spring: Deadly Autumn of the Vietnam War was to enlighten readers about these atrocities. But as he closes his thesis, he alerts readers to another simple truth: many of these same chemicals are still being used in our everyday lives, our homes and gardens today. Oh sure, the EPA and departments of health and agriculture are a lot more diligent in their testing today…or at least we have to hope so. But how do we know what the long-term effects will be to any such exposure, not to mention the chemicals in prescription drugs, etc? Just this morning, I got notice of worldwide recall of a blood pressure medication (Valsartan) I’ve been using for decades because of some chemical in it that can cause liver cancer. Between all the pollution in the air, the chemicals in our genetically modified foods, our drugs, and the rest, what hope do we, or our children and their children have of living a disease and illness-free life? Dream on. Thanks for writing this important book, Patrick Hogan.

Jack Magnus

Silent Spring: Deadly Autumn of the Vietnam War is a nonfiction memoir written by Patrick Hogan. While many Americans considered the Vietnam War to finally be over with the fall of Saigon, for countless in-country veterans and their families, the War is still definitely not over. They’ve been battling with the DVA, the US Government and the Department of Defense now for decades in an attempt to get coverage and compensation for the illnesses and injuries received as a result of the highly toxic herbicides and insecticides that were regularly sprayed in an even more deadly combination with contaminated jet fuel. Add to that the regular burning of human waste that occurred in their camps, and the stage was set for what Hogan rightly calls the biggest environmental disaster this country has ever known. Our veterans were exposed to dioxin and other substances, which are deadly in minute amounts, in the air they breathed, the food they ate, the clothing they wore. No one considered the fact that the different chemicals would combine and become even more deadly, and no one has been willing to stand up and admit to those soldiers that their suffering was indeed caused by the substances the government used. Many believe that the government is just waiting for them to all die out, but their children and grandchildren still carry the genetic ravages wreaked on the young men who went to Nam to serve their country. Silent Spring: Deadly Autumn of the Vietnam War caught my eye because Rachel Carson’s pioneering environmental science work, Silent Spring, had made such a profound impact upon me years ago when I discovered it while researching a term paper. I felt sure that Hogan’s use of that title meant he had another equally dire and important message to share with his readers -- and he certainly did. I was stunned as I read about the toxic soups that were atomized and sprayed without any regard to the boots on the ground, and I became infuriated as I learned that the toxic nature of those chemicals was already understood; that their use was callous and calculating and that the bottom line in the way the vets have been treated for decades was to save face and to protect the industries responsible for those chemicals. Worse still, they are even now trying to market many of those products in altered form for home and commercial use. Hogan’s book is impeccably researched and masterfully written. He shares with the reader his years of studies into chemicals and their actions and interactions, and he does so in a manner that is clear and easily understood by the layman. He also honestly and frankly shares his own health conditions to allow readers to understand just how much damage in-country veterans suffered and are continuing to suffer because of the environmental firestorm unleashed upon them by their own government. Silent Spring: Deadly Autumn of the Vietnam War is a call to action that everyone should read and then start asking their members of Congress to address -- while those veterans are still alive. It’s a crucially important work and it’s most highly recommended.

Lucinda E Clarke