- Clerc Center | PK-12 & Outreach

- KDES | PK-8th Grade School (D.C. Metro Area)

- MSSD | 9th-12th Grade School (Nationwide)

- Gallaudet University Regional Centers

- Parent Advocacy App

- K-12 ASL Content Standards

- National Resources

- Youth Programs

- Academic Bowl

- Battle Of The Books

- National Literary Competition

- Youth Debate Bowl

- Youth Esports Series

- Bison Sports Camp

- Discover College and Careers (DC²)

- Financial Wizards

- Immerse Into ASL

- Alumni Relations

- Alumni Association

- Homecoming Weekend

- Class Giving

- Get Tickets / BisonPass

- Sport Calendars

- Cross Country

- Swimming & Diving

- Track & Field

- Indoor Track & Field

- Cheerleading

- Winter Cheerleading

- Human Resources

- Plan a Visit

- Request Info

- Areas of Study

- Accessible Human-Centered Computing

- American Sign Language

- Art and Media Design

- Communication Studies

- Criminal Justice

- Data Science

- Deaf Studies

- Early Intervention Studies Graduate Programs

- Educational Neuroscience

- Hearing, Speech, and Language Sciences

- Information Technology

- International Development

- Interpretation and Translation

- Linguistics

- Mathematics

- Philosophy and Religion

- Physical Education & Recreation

- Public Affairs

- Public Health

- Sexuality and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Theatre and Dance

- World Languages and Cultures

- B.A. in American Sign Language

- B.A. in Biology

- B.A. in Communication Studies

- B.A. in Communication Studies for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.A. in Deaf Studies

- B.A. in Deaf Studies for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.A. in Education with a Specialization in Early Childhood Education

- B.A. in Education with a Specialization in Elementary Education

- B.A. in English

- B.A. in English for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.A. in Government

- B.A. in Government with a Specialization in Law

- B.A. in History

- B.A. in Interdisciplinary Spanish

- B.A. in International Studies

- B.A. in Mathematics

- B.A. in Philosophy

- B.A. in Psychology

- B.A. in Psychology for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.A. in Social Work (BSW)

- B.A. in Sociology with a concentration in Criminology

- B.A. in Theatre Arts: Production/Performance

- B.A. or B.S. in Education with a Specialization in Secondary Education: Science, English, Mathematics or Social Studies

- B.S. in Accounting

- B.S. in Accounting for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.S. in Biology

- B.S. in Business Administration

- B.S. in Business Administration for Online Degree Completion Program

- B.S. in Data Science

- B.S. in Information Technology

- B.S. in Mathematics

- B.S. in Physical Education and Recreation

- B.S. in Public Health

- B.S. in Risk Management and Insurance

- General Education

- Honors Program

- Peace Corps Prep program

- Self-Directed Major

- M.A. in Counseling: Clinical Mental Health Counseling

- M.A. in Counseling: School Counseling

- M.A. in Deaf Education

- M.A. in Deaf Education Studies

- M.A. in Deaf Studies: Cultural Studies

- M.A. in Deaf Studies: Language and Human Rights

- M.A. in Early Childhood Education and Deaf Education

- M.A. in Early Intervention Studies

- M.A. in Elementary Education and Deaf Education

- M.A. in International Development

- M.A. in Interpretation: Combined Interpreting Practice and Research

- M.A. in Interpretation: Interpreting Research

- M.A. in Linguistics

- M.A. in Secondary Education and Deaf Education

- M.A. in Sign Language Education

- M.S. in Accessible Human-Centered Computing

- M.S. in Speech-Language Pathology

- Master of Public Administration

- Master of Social Work (MSW)

- Au.D. in Audiology

- Ed.D. in Transformational Leadership and Administration in Deaf Education

- Ph.D. in Clinical Psychology

- Ph.D. in Critical Studies in the Education of Deaf Learners

- Ph.D. in Hearing, Speech, and Language Sciences

- Ph.D. in Linguistics

- Ph.D. in Translation and Interpreting Studies

- Ph.D. Program in Educational Neuroscience (PEN)

- Psy.D. in School Psychology

- Individual Courses and Training

- National Caregiver Certification Course

- CASLI Test Prep Courses

- Course Sections

- Certificates

- Certificate in Sexuality and Gender Studies

- Educating Deaf Students with Disabilities (online, post-bachelor’s)

- American Sign Language and English Bilingual Early Childhood Deaf Education: Birth to 5 (online, post-bachelor’s)

- Early Intervention Studies

- Certificate in American Sign Language and English Bilingual Early Childhood Deaf Education: Birth to 5

- Online Degree Programs

- ODCP Minor in Communication Studies

- ODCP Minor in Deaf Studies

- ODCP Minor in Psychology

- ODCP Minor in Writing

- University Capstone Honors for Online Degree Completion Program

Quick Links

- PK-12 & Outreach

- NSO Schedule

I-Search Paper Format Guide

202.448-7036

An I-Search paper is a personal research paper about a topic that is important to the writer. An I-Search paper is usually less formal than a traditional research paper; it tells the story of the writer’s personal search for information, as well as what the writer learned about the topic.

Many I-Search papers use the structure illustrated in this framework:

The Search Story

- Hook readers immediately. Your readers are more likely to care about your topic if you begin with an attention-getting opener. Help them understand why it was important for you to find out more about the topic.

- Explain what you already knew about your topic. Briefly describe your prior knowledge about the topic before you started your research.

- Tell what you wanted to learn and why . Explain why the topic is important to you, and let readers know what motivated your search.

- Include a thesis statement. Turn your research question into a statement that is based on your research.

- Retrace your research steps. Tell readers about your sources – how you found them and why you used them.

The Search Results

Describe the significance of your research experience. Restate your thesis.

Discuss your results and give support . Describe the findings of your research. Write at least one paragraph for each major research result. Support your findings with quotations, paraphrases, and summaries of information from sources.

Search Reflections

Describe important results of your research. Support your findings.

Reflect on your search . Describe what you learned and how your research experience might have changed you and your future. Also, remind readers of your thesis.

Source: This Writer’s Model has been formatted according to the standards of the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers , Fifth Edition | Copyright © by Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. All rights renewed.

Citations and References

202-448-7036

At a Glance

- Quick Facts

- University Leadership

- History & Traditions

- Accreditation

- Consumer Information

- Our 10-Year Vision: The Gallaudet Promise

- Annual Report of Achievements (ARA)

- The Signing Ecosystem

- Not Your Average University

Our Community

- Library & Archives

- Technology Support

- Interpreting Requests

- Ombuds Support

- Health and Wellness Programs

- Profile & Web Edits

Visit Gallaudet

- Explore Our Campus

- Virtual Tour

- Maps & Directions

- Shuttle Bus Schedule

- Kellogg Conference Hotel

- Welcome Center

- National Deaf Life Museum

- Apple Guide Maps

Engage Today

- Work at Gallaudet / Clerc Center

- Social Media Channels

- University Wide Events

- Sponsorship Requests

- Data Requests

- Media Inquiries

- Gallaudet Today Magazine

- Giving at Gallaudet

- Financial Aid

- Registrar’s Office

- Residence Life & Housing

- Safety & Security

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- University Communications

- Clerc Center

Gallaudet University, chartered in 1864, is a private university for deaf and hard of hearing students.

Copyright © 2024 Gallaudet University. All rights reserved.

- Accessibility

- Cookie Consent Notice

- Privacy Policy

- File a Report

800 Florida Avenue NE, Washington, D.C. 20002

ENGL 1A - I-Search

- Background info

- Detailed Information

- Evaluate your sources

- Cite your sources

The I-Search paper is designed to teach the writer and the reader something valuable about a chosen topic and about the nature of searching and discovery. As opposed to the standard research paper where the writer usually assumes a detached and objective stance, the I-Search paper allows you to take an active role in your search, to experience some of the hunt for facts and truths first-hand, and to provide a step-by-step record of the discovery.

I mage by geralt, free for commercial use.

Your assignment

The first rule of the I-Search paper is to select a topic that genuinely interests you and that you need to know more about. In this case, you will be researching some aspect of Identity (Race, Class, Gender) that you are interested in or most concerned about exploring.

The I-Search paper will be written in four integrated sections:

Part I: Introduction (1-2 Pages)

Part II: What I know, Assume, or Imagine (1-2 Pages)

Part III: The Search -Two Parts (2-3 Pages)

Part IV: What I Discovered- Two Parts (4-5 pages)

Part V: References Page (1-2 pages)

I. Introduction:

The introduction of your essay should give your reader some indication of why you have chosen to write about this particular topic. Keep in mind that your essay needs to have some point. What message do you want to communicate to your reader? The message needs to be something more than "I believe…I think…I feel…." The purpose of this essay will be to inform your reader of your (1) original assumptions, (2) the information you found on your search, and (3) your discoveries.

II. What I Want to Know, What I Assume or Imagine:

Before conducting any formal research, write a section in which you explain to the reader what you think you know, what you assume, or what you imagine about your topic. There are no wrong answers here. You are basically establishing your hypothesis. For this research project, it is most effective for your hypothesis or thesis to be presented as a series of three or four questions you plan to explore answers to in the following sections.

III. The Search:

Test your knowledge, assumptions, or conjectures by researching your paper topic thoroughly. Conducting a phone or face to face interview with someone who is a KEY PLAYER: one who may be able to change or improve the problem you are addressing. If your Identity Topic involves researching is a cultural concern, perhaps you can interview a family or community member who is working towards positive change. A second requirement will be to visit Merritt’s Online Library and investigate the abundant books and Internet resources available. Other first-hand activities that may provide valuable information include writing letters, and/ or making telephone calls. Also, consult useful second-hand sources such as books, magazines, newspapers, and documentaries. Be sure to record all the information you gather.

Write up your search in a narrative form, relating the steps of the discovery process (this means that you are going to tell the story of what you did to research this topic and what you learned in the process). Do not feel obligated to tell everything (you don't have to tell us the boring stuff but highlight the happenings and facts you uncovered that were crucial to your hunt and contributed to your understanding of the information.

Your Hunt for Information: This is the story of your hunt for information. For this section, you will rely on your Journal entries. Summarize your journey from Day One of your I-Search to the finish line. Make sure to summarize how you began your research. What process did you use to conduct your research? What types of searches did you try and how did they turn out? Include your opinion on sources and the information you discovered. Show the steps you took in your thinking/brainstorming. What challenges did you experience along the way? How did you handle these challenges?

IV: What I Discovered: This section will be divided into two parts.

1) This section must be written in an objective tone which means that you should avoid using personal statements such as “I think”, “I believe”, or “I feel.” Save your opinions for your reflection. Where were each of the sources found? What did each source reveal? Did the sources effectively answer any of your questions? How? Describe each source as it relates to your original research questions (listed at the end of Part II: What I Want to Know).

2) Your Reflection: What did you learn about yourself as a researcher? Did anything about this research process surprise you? Include your opinion on sources and the information you discovered. For example, did you realize you had a bigger interest in this social issue than you originally anticipated? Reflect upon the entire search experience, not only what you got out of it, not only what you have learned, but how this search has changed your life. What do you now know about searching for information that you didn’t know before? To answer this question, you will describe those findings that meant the most to you. What are the implications of your findings? How might your newly found knowledge affect your future?

After concluding your search, compare what you thought you knew, assumed, or imagined with what you discovered, assess your overall learning experience, and offer some personal commentary about the value of your discoveries and/or draw some conclusions. Some questions that you might consider at this stage:

How accurate were your original assumptions?

What new information did you acquire?

What did you learn that surprised you?

Overall, what value did you derive from the process of searching and discovery?

Don’t just do a question/answer conclusion. Go back to the main point you want to make with this essay. What final message do you want to leave with your readers?

V. REFERENCES (APA Format):

You will be required to attach a formal bibliography, following the APA format, listing the sources you consulted to write your I-Search paper. You will need to use a minimum of six different sources. One of your sources has been chosen for you which is “The Banking Concept of Education” by Paulo Freire. Your research requires you to find five more sources: 1 – interview or survey (for extra credit), 1-book or e-book, 1-magazine, journal, or newspaper article, and 3- Internet sources. (This means that you will have at least 6 sources in your bibliography, and I would expect to see these sources cited in the body of your paper.) There are also Internet resources that can assist you with APA Documentation and other aspects of writing a research paper.

Keeping your audience firmly in mind will be an important key to success with this assignment. You don’t want to write this up as if it is simply a long journal entry. Think of your audience as freshmen in college or university transfer students who might also be interested in the information you have collected. Remember, writing is a form of communication, and you need to be clear in your own mind who you are trying to communicate with and what you want to communicate to those people. Your I-Search will need to be a MINIMUM of 8 FULL pages. Note: The 8 pages do NOT include Title Page, Cover Letter, Abstract, References Page, or Appendices.

- Next: Strategy >>

- Last Updated: Mar 6, 2023 4:33 PM

- URL: https://merritt.libguides.com/isearch

Promoting Student-Directed Inquiry with the I-Search Paper

About this Strategy Guide

The sense of curiosity behind research writing gets lost in some school-based assignments. This Strategy Guide provides the foundation for cultivating interest and authority through I-Search writing, including publishing online.

Research Basis

Strategy in practice, related resources.

The cognitive demands of research writing are numerous and daunting. Selecting, reading, and taking notes from sources; organizing and writing up findings; paying attention to citation and formatting rules. Students can easily lose sight of the purpose of research as it is conducted in “the real world”—finding the answer to an important question.

The I-Search (Macrorie, 1998) empowers students by making their self-selected questions about themselves, their lives, and their world the focus of the research and writing process. The strong focus on metacognition—paying attention to and writing about the research process methods and extensive reflection on the importance of the topic and findings—makes for meaningful and purposeful writing.

Online publication resources such as blogging software make for easy production of multimodal, digital writing that can be shared with any number of audiences.

Assaf, L., Ash, G., Saunders, J. and Johnson, J. (2011). " Renewing Two Seminal Literacy Practices: I-Charts and I-Search Papers ." English Journal , 18(4), 31-42.

Lyman, H. (2006). “ I-Search in the Age of Information .” English Journal , 95(4), 62-67.

Macrorie, K. (1998). The I-Search Paper: Revised Edition of Searching Writing . Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann-Boynton/Cook.

- Before introducing the I-Search paper, set clear goals and boundaries for the assignment. In some contexts, a completely open assignment can be successful. In others, a more limited focus such as research on potential careers (e.g., Lyman, 2006) may be appropriate.

- Introduce the concept of the I-Search by sharing with students that they will be learning about something that is personally interesting and significant for them—something they have the desire to understand more about. Have students generate a list of potential topics.

- Review student topic lists and offer supportive feedback—either through written comments or in individual conferences—on the topics that have the most potential for success given the scope of the assignment and the research resources to which students will have access.

- After offering feedback, have students choose the topic that seems to have the most potential and allow them to brainstorm as many questions as they can think of. When students have had plenty of time to ponder the topic, ask them to choose a tentative central question—the main focus for their inquiry—and four possible sub-questions—questions that will help them narrow their research in support of their main question. Use the I-Search Chart to help students begin to see the relationships among their inquiry questions.

- Begin the reflective component of the I-Search right away and use the I-Search Chart to help students write about why they chose the topic they did, what they already know about the topic, and what they hope to learn from their research. Students will be please to hear at this point that they have already completed a significant section of their first draft.

- Engage reader’s attention and interest; explain why learning more about this topic was personally important for you.

- Explain what you already knew about the topic before you even started researching.

- Let readers know what you wanted to learn and why. State your main question and the subquestions that support it.

- Retrace your research steps by describing the search terms and sources you used. Discuss things that went well and things that were challenging.

- Share with readers the “big picture” of your most significant findings.

- Describe your results and give support.

- Use findings statements to orient the reader and develop your ideas with direct quotations, paraphrases, and summaries of information from your sources.

- Properly cite all information from sources.

- Discuss what you learned from your research experience. How might your experience and what you learned affect your choices or opportunities in the future.

- At this point, the research process might be similar to that of a typical research project except students should have time during every class period to write about their process, questions they’re facing, challenges they’ve overcome, and changes they’ve made to their research process. Students will not necessarily be able to look ahead to the value of these reflections, so take the time early in the process to model what reflection might look like and offer feedback on their early responses. You may wish to use the I-Search Process Reflection Chart to help students think through their reflections at various stages of the process.

- Support students as they engage in the research and writing process, offering guidance on potential local contacts for interviews and other sources that can heighten their engagement in the authenticity of the research process.

- To encourage effective organization and synthesis of information from multiple sources, you may wish to have students assign a letter to each of their questions (A through E, for example) and a number to each of their sources (1 through 6, for example). As they find content that relates to one of their questions, they can write the corresponding letter in the margin. During drafting, students can use the source numbers as basic citation before incorporating more sophisticated, conventional citation.

How to Start a Blog

Blog About Courage Using Photos

Creating Character Blogs

Online Safety

Teaching with Blogs

- Content is placed on appropriate, well-labeled pages. The pages are linked to one another sensibly (all internal links).

- Images/video add to the reader’s understanding of the content, are appropriately sized and imbedded, and are properly cited.

- Text that implies a link should be hyperlinked. Internal links (to other pages of the blog) stay in the same browser window; External links (to pages off the blog) open in a new browser window.

- Lesson Plans

- Student Interactives

This tool allows students to create an online K-W-L chart. Saving capability makes it easy for them to start the chart before reading and then return to it to reflect on what they learned.

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

Writing Assignment #3 will be a personal research narrative essay, which sometimes is referred to as an “I-Search” paper. Background to this Essay: In many classes in the past, you might have been instructed never to use the word “I” in your writing. However, throughout this class, in both the response essay and the reflective annotated bibliography, you have been instructed that the use of the word “I” was totally acceptable, even encouraged. In this essay, this use of first-person point of view continues. This essay is a research essay in which you use the word “I.” Ken Macrorie, a professor at Western Michigan University, wrote a textbook in 1980 called The I-Search Paper. In the book, Macrorie criticized traditional research papers that students were often asked to produce in classes. He designed, instead, a type of research paper that asked students to use the first-person point of view (“I”) in their papers, encouraged them to explore topics that were of interest to them, and required that they comment on their research journey in finding sources and information on their topics as much as on any arguments or conclusions they were making on their topics. This writing assignment in WRTG 291 is informed by Macrorie’s approach, although it does not involve all elements of the research process he asked for. In the e-reserves section of our class, you will find a chapter from Linda Bergmann, “Writing a Personal Research Narrative.” Please access that chapter. In that chapter, please read “The Personal Research (‘I Search’) Paper,” starting on page 160. On page 160, Bergmann (2010) writes: Although an I-Search assignment calls for a personal narrative, like most academic writing it is written to communicate to a particular audience, not for the writer alone. Its purpose is to help you discover and communicate the personal and professional significance of your research to a particular audience. Moreover, pages 161-162 in Bergmann’s chapter list some steps to take in organizing and preparing to write your paper. Sample Personal Research Narrative Essays: On pages 162-166 of Bergmann's chapter is a sample personal research narrative essay. Another sample I-Search paper can be seen by clicking here, although this example has fewer sources and fewer scholarly sources than this assignment calls for. Moving from the Reflective Annotated Bibliography to the Personal Research Narrative: For writing assignment #2, you wrote a reflective annotated bibliography on a topic related to technology. In that assignment, for each of the articles you found, you wrote not only a précis of the article but also some vocabulary, reflection, and quotes from the article. Hopefully through that assignment, you developed an interest in a focused aspect of your topic. The following describe some examples of focusing your topic: •You may have conducted research on whether Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) are effective classroom environments. For writing assignment #2, you may have found 5-6 articles on MOOCs in general. Perhaps, as a result of your findings, you have now done more research and have focused on MOOCs for a particular field of study (e.g., computer programming or creative writing). You then found more articles related to not only MOOCs but also MOOCs for learning computer programming or MOOCs for learning creative writing. •You may have conducted research on cybersecurity. For writing assignment #2, you may have found 5-6 articles on cybersecurity as a broad topic. Perhaps, as a result of your findings, you have now done more research and have focused on cybersecurity and mobile devices. You then found more articles related to not only cybersecurity as a general topic but specifically on cybersecurity and mobile devices. •You may have conducted research on technology in the health care industry. For writing assignment #2, you may have found 5-6 articles on technology in the health care industry. Perhaps, as a result of your findings, you have now done more research and have focused on the cloud computing in the health care industry. You then found more articles specifically on this topic. It is this research experience on which you will write the personal research narrative. Examining the Sample Personal Research Narrative in Bergmann's Chapter: Note how, in the sample student personal research narrative on page 162, the student begins by providing the background that gave him interest in the topic. He then discusses his first steps in researching the topic. As he describes his steps in the research process, he uses expressions like, “I was astounded by…” or “This idea seemed valid to me, but…” or “…let me to wonder…” or “At this point in my exploration I have come up with a slight dilemma.” For your personal research narrative, you want to follow the same pattern. Describe to the reader what you thought when you started researching, what you already knew about the subject, what interested you in the subject, etc. Then describe your various steps, commenting on what surprised you, what ideas did not seem valid to you, what research articles you may have questioned, etc. You might consider your response essay, which was the first essay you wrote for this class. The personal research narrative is, in some ways, an expanded response essay. In the personal research narrative, you may be responding to several authors while providing a narrative of your thought process and learning process throughout your research journey. Requirements: Your paper should be 1800-2400 words. It should include at least ten sources, six of which should be scholarly. The sources are to be cited and listed in APA format. Additional resources: In our class, in the e-reserves section, we have a chapter from the book by Graff, G. and Birkenstein, C, They Say / I Say: The Moves that Matter in Academic Writing with Readings. The chapter mentions various techniques to apply in stating what an author said and your response to the author. As was recommended for the response essay, it is recommended that you read through that chapter so that you might apply these techniques to this essay.

- Apply to UVU

A Change from a Traditional Research Paper – the I-Search Paper

by Dr. Becky Rogers, Instructional Designer III

One challenge faculty members face is how to incorporate writing into their courses in both meaningful and engaging ways. Students typically complain about writing research papers , and instructors decry the long hours to both grade and give critical feedback. We know the practice of writing academic papers containing clear analysis and correct formatting is important for a good education and future success, but the reality of student submissions is often disappointing.

We suggest an alternative to the traditional paper. It is more informal and allows students freedom to choose topics that interest them. It also guides them through the research process while engaging students in selected areas. This alternative is called an I-Search paper , and we will discuss its key components below.

First, the student choses a specific area in the course curriculum that has piqued their interest. Once the student selects the topic, they put it into question form to guide their research.

Here are a few examples of the types of questions they could select:

- What are our physical reactions to emotions and why do we have them?

- How does playing with Legos affect the brain?

- What is the “cloud” and how are things stored there?

- How do vocal cords work and how can one’s pitch go higher and lower?

- What is military surveillance like today?

Next, the student creates a hook. They must figure out a way to excite their readers and make them want to read more. Here is an example:

On the dresser in my room is a very special object, a cup made by my grandmother. Grandma Kasamoto was a potter. Years ago, when I was five, I saw this pretty cup sitting on a shelf in Grandma’s pottery shop. It was white, with delicate green stems and leaves painted on it. The stems curled up the sides of the cup and ended in tiny purple flowers.

The student then states the question they will research and why it is important to them. In this particular example, the student wanted to know the process her grandmother would have used to create the cup. This is followed by a synopsis of what the student already knows about the topic and then an outline of the additional information they are interested in. By breaking the main question into narrower questions, it controls the scope of the research.

After that, the student begins researching their questions. It is important that they take notes about what they are learning and keep track of the resources they use. This information will be crucial when they summarize their research process. It is a good idea to have suggestions for where to look for information and how to evaluate the credibility of a source. Once research is complete, the student will summarize the process they used to research their questions and then provide their key findings.

Finally, the student will discuss what they have learned and how it helped answer their questions. This part of their paper should include a reflection piece describing how the answers have informed them and how they can be used in their lives. At this point they can also determine additional questions they would like to explore at a later time.

English 1 Honors & Advanced Communications Web Portal (n.d.) The I-Search Paper. Retrieved from: https://mrsspeachenglish.weebly.com/i-search-paper.html

Gallaudet University. (n.d.). I-Search Paper Format Guide. Retrieved from: https://www.gallaudet.edu/tutorial-and-instructional-programs/english-center/citations-and-references/i-search-paper-format-guide/

Gallaudet University. (n.d.). Writing an I-Search Paper . Retrieved from: https://www.gallaudet.edu/Documents/Academic/CLAST/TIP/writing%20an%20I-search%20paper.pdf

I Search Topics . Retrieved from: https://elalibman.com/Site/I-Search_Topics.html

Yamato, Michiko. (2000). How Memories are Made. Retrieved from: https://www.yumpu.com/en/document/read/25196071/i-search-paper

Utah Valley University

I-Search Topics

I-Search is a project that we present in early November and the students work on until mid-December. Our goal is to teach students to use research tools to find answers to questions. Each student comes up with a question and hypothesis and works to find the answer, if there is one. We find that by having students work on a topic of interest, they learn the tools of research more easily.

Here are some ideas to think about:

Ideas for I-Search topics

How do humans’ ability to smell differ from dogs? / Why are dogs senses more acute than human

senses?

How and why do optical illusions work?

How does flavor affect our eating habits?

What is colon cancer? What are colon cancer’s cure possibilities?

How do GPS systems work?

Do helmets protect your brain sufficiently while playing contact sports?/ How can football

equipment prevent concussions?

What are deep sea animals adaptions to an underwater environment?

How do computer viruses spread and in what ways do they affect computers?

How does pressure and lack of light affect deep sea creatures senses?

How do our eyes and brain turn pictures into movies?

Why do people get freckles?

How are gems classified?

Why and how has Batman changed over the decades and how?

Why and how was Stonehenge built?

What are black holes?

How are cheeses from the milk of a cow made to taste, look and feel differently?

What would be the effect of krill extinction on the ocean ecosystem?

How does smell affect people? / How do advertisers use smell?

How did Cleopatra come to power in Egypt and what did she do during her reign?

What causes dreaming? / What influences dreams and can they be controlled?

What is life like in a beehive? / What is causing beehive collapse? / Why are bees important?

Why did Qin Shi Huang Di build such a large tomb?

What do people do when they get scared both inside and outwardly?

How does the shape of a boat’s hull affect how much weight it can hold?

What is the life like of a minor league baseball player?

How did James Cameron create the set for the movie, “Titanic?”

How are ads constructed to appeal to people?

How do jellyfish survive in open waters?

How does caffeine affect the brain?

How have the uses and preparation of coffee changed throughout time?

I s nuclear power safe for the environment?

What are the benefits and drawbacks of wind power?

What influences dreams and can they be controlled?

How does how you throw a baseball affect its speed?

How does the flex of a hockey stick affect ones shot?

How does texting affect literacy?

How did sailors in ancient times navigate?

What are the major theories explaining the disappearance of dinosaurs?

How do advertisers use music to affect sales?

When does synesthesia develop and how long does it last?

How are energy drinks supposed to work? Are there problems with energy drinks?

Why do people get a brain freeze and what causes it?

What causes one to yawn and why are yawns contagious?

How does color affect mood?

How do dogs communicate with each other and with humans?

How do vaccinations work and what are the benefits and risks?

How are video games beneficial to children? / What effects do video games have on your brain and body?

How does the brain remember information?

What technologies are there for people to save energy in their homes?

How have penguins adapted to survive in various environments?

Are there Earth-like planets and how do we find them?

Do lie detectors accurately determine truthful statements?

How does color affect consumer decisions?

How does a hybrid car save energy?

How do orcas act in captivity?

How does video game music affect the game?

How is ultrasound used?

How effectively does the baseball statistic WAR (Wins Above Replacement) assess a ballplayer’s overall performance?

How does chocolate affect mood? / How does chocolate affect your brain and body?

How did the I-phone change the world?

What are some common sleep disorders, why do they happen, and how are they treated?

How does dance affect your mind?

What are the theories and truths about crop circles ?

How does movement affect learning?

Why do humans need sleep?

What places in a batting order are given to the best batters and why?

How does the spin on a baseball effect the trajectory? / How does holding a baseball effect how it

curves?

How does hypnosis work?

How do octopi defend themselves?

Why do birds sing? / How do birds adapt to their environments?

How are coral reefs formed and what harms them?

Have have concussion tests and treatments changed?

How does exposure to sun effect the skin?

How do gravity and magnetism relate to each other?

How does stealth technology shield aircraft from radar?

How does climbing Mt. Everest affect your body?

When were traffic lights invented and how have they helped and hindered drivers in society?

What causes tornados and water spouts?

What are our physical reactions to emotions and why do we have them?

Does listening to a specific type of music affect intelligence?

Why do we like sweets?

How does night vision work?

How do tablets (and or handheld devices) affect children’s learning?

How does pressure affect how rocks form and erode?

How do planes fly?

What animals have pass the mirror test and why does it show self-awareness?

What are the good components of a good baseball swing.

How does playing with Legos affect the brain?

How do ant’s colonies work so well even though ants are so small?

What are the causes of sleep walking? Is it curable?

How can bio-mimicry effect our lives? / What are the uses of bio-mimicry for people?

How do dolphins communicate?

What are different coding languages and how are they used?

How does proximity to light speed affect you?

How do amusement park lines affect customer enjoyment?

What is a peanut allergy? Can it be cured?

How do babies learn really quickly?

Why do we sleep?

How can computers be used to help people with....(any of various disabilities)?

How does having a pet affect your mood and life span? Do different types of pets affect life differently?

How do estuaries and wetlands affect the environment?

How has Apple changed the world?

How does music affect Alzheimer’s disease?

What are the risks of climate change and global warming on ......?

How does music affect the human brain?

What are sinkholes and how are they formed?

Can dogs catch sicknesses and diseases from humans?

Why are insects attracted to light?

What are the theories behind the Bermuda Triangle?

How are jaguars (or any other animal) adapted to their environment?

How does drinking soda affect a person’s health?

How has ballet hanged since it started?

What causes stress and how do we resolve it?

How does a search engine work?

Why is laughing contagious and how does laughing affect your mood?

How do people use sign language? What are its origins?

Does the celebration of holidays effect people”s behavior, mood and beiefs.

How and why did the Van Sweringen brothers establish Shaker Heights?

What causes fear and what are the body’s reaction?

Why and how do touch screens react to certain surfaces?

What causes bioluminescence and how does it help the creatures who exhibit it?

How will aquaponics affect the future of farming?

What is the relationship of major league baseball teams and farm league teams?

How have swimsuits changed over time and how does that effect how fast people swim?

What are allergies and how do they differ in various parts of the world?

What are the effects of steroids on the human body?

How are vitamins made and how do we digest them?

What is the “cloud” and how are things stored there?

How are marine animals affected by water pollution?

How is snow formed?

How do injuries affect a player’s performance in baseball?

Why does the Earth move and we don’t feel it? How do we perceive motion?

How do cats communicate with each other and humans? What body parts to they use?

Does smiling affect life span?

How do vocal cords work and how can one’s pitch go higher and lower?

How has angling changed over the years and what is the effect of equipment?

What are phobias and how does the body react to them?

How do elephants mourn their dead?

How do mood rings/necklaces change color and do they really tell how you are feeling?

How does birth order affect the personalities of children?

How does the ear work and why can some people hear better than others?

How does Lake Erie water pollution hurt northeastern Ohio?

How does sugar affect the body?

What factors affect good sleep?

How do different seahorses adapt to their surroundings?

How was the skateboard invented and how has it changed over the years?

Are redheads going extinct?

What does fear do to the body?

What is military surveillance like today?

How do arthropods sense the world?

How does coffee get from the plant to the beans we buy?

How does leukemia affect your body?

How does being bilingual affect the brain?

Home › Blog Topics › The I-Search Paper: Getting Students Excited about Research

The I-Search Paper: Getting Students Excited about Research

By Karin Greenberg on 01/25/2021 • ( 1 )

Whenever I teach a research lesson to a class of high school students, I notice the lack of enthusiasm for the project they’re about to start. I find myself working hard to convince them that research is a rewarding endeavor and that the process can be exciting and fun. After I’ve gone through the details of how to use databases and other resources to search for information, I answer any questions they have. Like a thought bubble in a cartoon strip, each student’s question is accompanied by the unspoken words, “How can I get what I need quickly so I can be done with my assignment.”

Last week, while teaching research lessons to 9th-grade classes, I encountered something different. Maybe I was imagining it (we were on Zoom, after all), but the students seemed more interested in the work that was ahead of them. The reason, I believe, is that their English teacher assigned an I-Search paper, instead of the traditional research paper. Fueled by a topic that interests them, the I-Search paper includes information about their subject, but also catalogues their search processes and pushes them to analyze each step along their research paths.

Research is an acquired skill, one that is more important than ever in a time of continually flowing information and disinformation. Not only is responsible investigating necessary for finding credible information, but it also serves as a catalyst for critical thinking and analysis, tools that will benefit students in every area of their lives. Some high school students are actively involved in research programs in which they develop college-level abilities that will help them continue on a strenuous academic path. But for average students who are not afforded the extra attention, an I-Search paper can be a motivating factor in setting them on the right course toward inquiry and engagement.

Research Tips for Students:

- Sweet Search: Instead of using Google, which contains information that is not always credible, use Sweet Search, an academic search engine whose results are vetted by scholars and experts.

- Google Books: Take advantage of this database of millions of digitally scanned books and magazines from libraries around the world.

- Works Cited: Open up a blank Google Doc (or Microsoft Word Doc) where you can quickly paste a citation copied from a database.

- Database Tools: Become familiar with the tools on each of the school’s databases. The most important ones are the citation tool, the date limiter, and the icon that saves an article to Google Drive or your computer file.

- Search Terms: Practice finding different words or phrases for keywords used in your information search. If you’re having trouble, Google a term to find similar words commonly used to discuss it.

- Purdue OWL: Explore this comprehensive website that will help you check format, style, and many other areas of your research paper.

Work Cited:

Appling-Jenson, Brandy, Carolyn Anzia, and Kathleen G. 2013. “ Bringing Passion to the Research Process: The I-Search Paper.” 130-151.

Author: Karin Greenberg

Karin Greenberg is the librarian at Manhasset High School in Manhasset, New York. She is a former English teacher and writes book reviews for School Library Journal. In addition to reading, she enjoys animals, walking, hiking, and spending time with her family. Follow her book account on Instagram @bookswithkg.

Categories: Blog Topics , Student Engagement/ Teaching Models

Tags: collaboration , databases , high school library , I-Search paper , library lessons , Research , search engines , student engagement , technology

Great article! Self-determination theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000) backs up Ms. Greenberg’s observation on the motivating power of student choice. An I-search paper is a great assignment at any time, but perhaps never more so than during a public health crisis which necessarily limits choice options.

The top list of academic search engines

1. Google Scholar

4. science.gov, 5. semantic scholar, 6. baidu scholar, get the most out of academic search engines, frequently asked questions about academic search engines, related articles.

Academic search engines have become the number one resource to turn to in order to find research papers and other scholarly sources. While classic academic databases like Web of Science and Scopus are locked behind paywalls, Google Scholar and others can be accessed free of charge. In order to help you get your research done fast, we have compiled the top list of free academic search engines.

Google Scholar is the clear number one when it comes to academic search engines. It's the power of Google searches applied to research papers and patents. It not only lets you find research papers for all academic disciplines for free but also often provides links to full-text PDF files.

- Coverage: approx. 200 million articles

- Abstracts: only a snippet of the abstract is available

- Related articles: ✔

- References: ✔

- Cited by: ✔

- Links to full text: ✔

- Export formats: APA, MLA, Chicago, Harvard, Vancouver, RIS, BibTeX

BASE is hosted at Bielefeld University in Germany. That is also where its name stems from (Bielefeld Academic Search Engine).

- Coverage: approx. 136 million articles (contains duplicates)

- Abstracts: ✔

- Related articles: ✘

- References: ✘

- Cited by: ✘

- Export formats: RIS, BibTeX

CORE is an academic search engine dedicated to open-access research papers. For each search result, a link to the full-text PDF or full-text web page is provided.

- Coverage: approx. 136 million articles

- Links to full text: ✔ (all articles in CORE are open access)

- Export formats: BibTeX

Science.gov is a fantastic resource as it bundles and offers free access to search results from more than 15 U.S. federal agencies. There is no need anymore to query all those resources separately!

- Coverage: approx. 200 million articles and reports

- Links to full text: ✔ (available for some databases)

- Export formats: APA, MLA, RIS, BibTeX (available for some databases)

Semantic Scholar is the new kid on the block. Its mission is to provide more relevant and impactful search results using AI-powered algorithms that find hidden connections and links between research topics.

- Coverage: approx. 40 million articles

- Export formats: APA, MLA, Chicago, BibTeX

Although Baidu Scholar's interface is in Chinese, its index contains research papers in English as well as Chinese.

- Coverage: no detailed statistics available, approx. 100 million articles

- Abstracts: only snippets of the abstract are available

- Export formats: APA, MLA, RIS, BibTeX

RefSeek searches more than one billion documents from academic and organizational websites. Its clean interface makes it especially easy to use for students and new researchers.

- Coverage: no detailed statistics available, approx. 1 billion documents

- Abstracts: only snippets of the article are available

- Export formats: not available

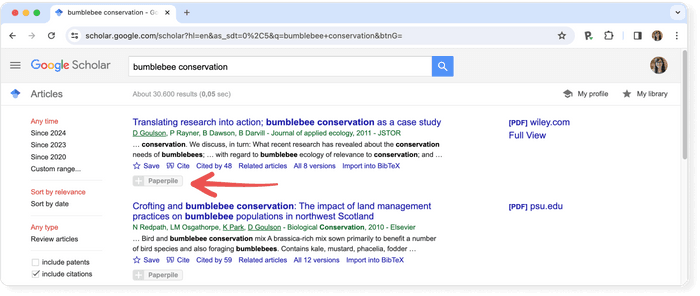

Consider using a reference manager like Paperpile to save, organize, and cite your references. Paperpile integrates with Google Scholar and many popular databases, so you can save references and PDFs directly to your library using the Paperpile buttons:

Google Scholar is an academic search engine, and it is the clear number one when it comes to academic search engines. It's the power of Google searches applied to research papers and patents. It not only let's you find research papers for all academic disciplines for free, but also often provides links to full text PDF file.

Semantic Scholar is a free, AI-powered research tool for scientific literature developed at the Allen Institute for AI. Sematic Scholar was publicly released in 2015 and uses advances in natural language processing to provide summaries for scholarly papers.

BASE , as its name suggest is an academic search engine. It is hosted at Bielefeld University in Germany and that's where it name stems from (Bielefeld Academic Search Engine).

CORE is an academic search engine dedicated to open access research papers. For each search result a link to the full text PDF or full text web page is provided.

Science.gov is a fantastic resource as it bundles and offers free access to search results from more than 15 U.S. federal agencies. There is no need any more to query all those resources separately!

What is an Essay?

10 May, 2020

11 minutes read

Author: Tomas White

Well, beyond a jumble of words usually around 2,000 words or so - what is an essay, exactly? Whether you’re taking English, sociology, history, biology, art, or a speech class, it’s likely you’ll have to write an essay or two. So how is an essay different than a research paper or a review? Let’s find out!

Defining the Term – What is an Essay?

The essay is a written piece that is designed to present an idea, propose an argument, express the emotion or initiate debate. It is a tool that is used to present writer’s ideas in a non-fictional way. Multiple applications of this type of writing go way beyond, providing political manifestos and art criticism as well as personal observations and reflections of the author.

An essay can be as short as 500 words, it can also be 5000 words or more. However, most essays fall somewhere around 1000 to 3000 words ; this word range provides the writer enough space to thoroughly develop an argument and work to convince the reader of the author’s perspective regarding a particular issue. The topics of essays are boundless: they can range from the best form of government to the benefits of eating peppermint leaves daily. As a professional provider of custom writing, our service has helped thousands of customers to turn in essays in various forms and disciplines.

Origins of the Essay

Over the course of more than six centuries essays were used to question assumptions, argue trivial opinions and to initiate global discussions. Let’s have a closer look into historical progress and various applications of this literary phenomenon to find out exactly what it is.

Today’s modern word “essay” can trace its roots back to the French “essayer” which translates closely to mean “to attempt” . This is an apt name for this writing form because the essay’s ultimate purpose is to attempt to convince the audience of something. An essay’s topic can range broadly and include everything from the best of Shakespeare’s plays to the joys of April.

The essay comes in many shapes and sizes; it can focus on a personal experience or a purely academic exploration of a topic. Essays are classified as a subjective writing form because while they include expository elements, they can rely on personal narratives to support the writer’s viewpoint. The essay genre includes a diverse array of academic writings ranging from literary criticism to meditations on the natural world. Most typically, the essay exists as a shorter writing form; essays are rarely the length of a novel. However, several historic examples, such as John Locke’s seminal work “An Essay Concerning Human Understanding” just shows that a well-organized essay can be as long as a novel.

The Essay in Literature

The essay enjoys a long and renowned history in literature. They first began gaining in popularity in the early 16 th century, and their popularity has continued today both with original writers and ghost writers. Many readers prefer this short form in which the writer seems to speak directly to the reader, presenting a particular claim and working to defend it through a variety of means. Not sure if you’ve ever read a great essay? You wouldn’t believe how many pieces of literature are actually nothing less than essays, or evolved into more complex structures from the essay. Check out this list of literary favorites:

- The Book of My Lives by Aleksandar Hemon

- Notes of a Native Son by James Baldwin

- Against Interpretation by Susan Sontag

- High-Tide in Tucson: Essays from Now and Never by Barbara Kingsolver

- Slouching Toward Bethlehem by Joan Didion

- Naked by David Sedaris

- Walden; or, Life in the Woods by Henry David Thoreau

Pretty much as long as writers have had something to say, they’ve created essays to communicate their viewpoint on pretty much any topic you can think of!

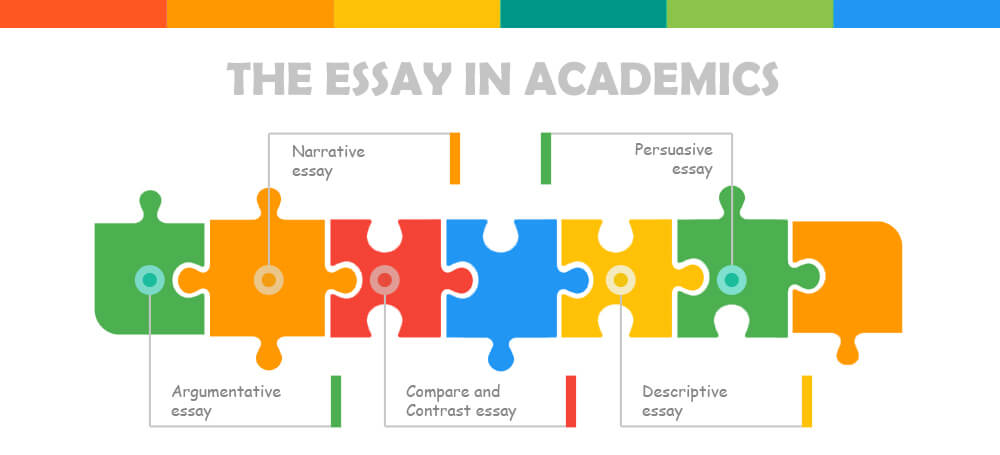

The Essay in Academics

Not only are students required to read a variety of essays during their academic education, but they will likely be required to write several different kinds of essays throughout their scholastic career. Don’t love to write? Then consider working with a ghost essay writer ! While all essays require an introduction, body paragraphs in support of the argumentative thesis statement, and a conclusion, academic essays can take several different formats in the way they approach a topic. Common essays required in high school, college, and post-graduate classes include:

Five paragraph essay

This is the most common type of a formal essay. The type of paper that students are usually exposed to when they first hear about the concept of the essay itself. It follows easy outline structure – an opening introduction paragraph; three body paragraphs to expand the thesis; and conclusion to sum it up.

Argumentative essay

These essays are commonly assigned to explore a controversial issue. The goal is to identify the major positions on either side and work to support the side the writer agrees with while refuting the opposing side’s potential arguments.

Compare and Contrast essay

This essay compares two items, such as two poems, and works to identify similarities and differences, discussing the strength and weaknesses of each. This essay can focus on more than just two items, however. The point of this essay is to reveal new connections the reader may not have considered previously.

Definition essay

This essay has a sole purpose – defining a term or a concept in as much detail as possible. Sounds pretty simple, right? Well, not quite. The most important part of the process is picking up the word. Before zooming it up under the microscope, make sure to choose something roomy so you can define it under multiple angles. The definition essay outline will reflect those angles and scopes.

Descriptive essay

Perhaps the most fun to write, this essay focuses on describing its subject using all five of the senses. The writer aims to fully describe the topic; for example, a descriptive essay could aim to describe the ocean to someone who’s never seen it or the job of a teacher. Descriptive essays rely heavily on detail and the paragraphs can be organized by sense.

Illustration essay

The purpose of this essay is to describe an idea, occasion or a concept with the help of clear and vocal examples. “Illustration” itself is handled in the body paragraphs section. Each of the statements, presented in the essay needs to be supported with several examples. Illustration essay helps the author to connect with his audience by breaking the barriers with real-life examples – clear and indisputable.

Informative Essay

Being one the basic essay types, the informative essay is as easy as it sounds from a technical standpoint. High school is where students usually encounter with informative essay first time. The purpose of this paper is to describe an idea, concept or any other abstract subject with the help of proper research and a generous amount of storytelling.

Narrative essay

This type of essay focuses on describing a certain event or experience, most often chronologically. It could be a historic event or an ordinary day or month in a regular person’s life. Narrative essay proclaims a free approach to writing it, therefore it does not always require conventional attributes, like the outline. The narrative itself typically unfolds through a personal lens, and is thus considered to be a subjective form of writing.

Persuasive essay

The purpose of the persuasive essay is to provide the audience with a 360-view on the concept idea or certain topic – to persuade the reader to adopt a certain viewpoint. The viewpoints can range widely from why visiting the dentist is important to why dogs make the best pets to why blue is the best color. Strong, persuasive language is a defining characteristic of this essay type.

The Essay in Art

Several other artistic mediums have adopted the essay as a means of communicating with their audience. In the visual arts, such as painting or sculpting, the rough sketches of the final product are sometimes deemed essays. Likewise, directors may opt to create a film essay which is similar to a documentary in that it offers a personal reflection on a relevant issue. Finally, photographers often create photographic essays in which they use a series of photographs to tell a story, similar to a narrative or a descriptive essay.

Drawing the line – question answered

“What is an Essay?” is quite a polarizing question. On one hand, it can easily be answered in a couple of words. On the other, it is surely the most profound and self-established type of content there ever was. Going back through the history of the last five-six centuries helps us understand where did it come from and how it is being applied ever since.

If you must write an essay, follow these five important steps to works towards earning the “A” you want:

- Understand and review the kind of essay you must write

- Brainstorm your argument

- Find research from reliable sources to support your perspective

- Cite all sources parenthetically within the paper and on the Works Cited page

- Follow all grammatical rules

Generally speaking, when you must write any type of essay, start sooner rather than later! Don’t procrastinate – give yourself time to develop your perspective and work on crafting a unique and original approach to the topic. Remember: it’s always a good idea to have another set of eyes (or three) look over your essay before handing in the final draft to your teacher or professor. Don’t trust your fellow classmates? Consider hiring an editor or a ghostwriter to help out!

If you are still unsure on whether you can cope with your task – you are in the right place to get help. HandMadeWriting is the perfect answer to the question “Who can write my essay?”

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

Find anything you save across the site in your account

Why A.I. Isn’t Going to Make Art

In 1953, Roald Dahl published “ The Great Automatic Grammatizator ,” a short story about an electrical engineer who secretly desires to be a writer. One day, after completing construction of the world’s fastest calculating machine, the engineer realizes that “English grammar is governed by rules that are almost mathematical in their strictness.” He constructs a fiction-writing machine that can produce a five-thousand-word short story in thirty seconds; a novel takes fifteen minutes and requires the operator to manipulate handles and foot pedals, as if he were driving a car or playing an organ, to regulate the levels of humor and pathos. The resulting novels are so popular that, within a year, half the fiction published in English is a product of the engineer’s invention.

Is there anything about art that makes us think it can’t be created by pushing a button, as in Dahl’s imagination? Right now, the fiction generated by large language models like ChatGPT is terrible, but one can imagine that such programs might improve in the future. How good could they get? Could they get better than humans at writing fiction—or making paintings or movies—in the same way that calculators are better at addition and subtraction?

Art is notoriously hard to define, and so are the differences between good art and bad art. But let me offer a generalization: art is something that results from making a lot of choices. This might be easiest to explain if we use fiction writing as an example. When you are writing fiction, you are—consciously or unconsciously—making a choice about almost every word you type; to oversimplify, we can imagine that a ten-thousand-word short story requires something on the order of ten thousand choices. When you give a generative-A.I. program a prompt, you are making very few choices; if you supply a hundred-word prompt, you have made on the order of a hundred choices.

If an A.I. generates a ten-thousand-word story based on your prompt, it has to fill in for all of the choices that you are not making. There are various ways it can do this. One is to take an average of the choices that other writers have made, as represented by text found on the Internet; that average is equivalent to the least interesting choices possible, which is why A.I.-generated text is often really bland. Another is to instruct the program to engage in style mimicry, emulating the choices made by a specific writer, which produces a highly derivative story. In neither case is it creating interesting art.

I think the same underlying principle applies to visual art, although it’s harder to quantify the choices that a painter might make. Real paintings bear the mark of an enormous number of decisions. By comparison, a person using a text-to-image program like DALL-E enters a prompt such as “A knight in a suit of armor fights a fire-breathing dragon,” and lets the program do the rest. (The newest version of DALL-E accepts prompts of up to four thousand characters—hundreds of words, but not enough to describe every detail of a scene.) Most of the choices in the resulting image have to be borrowed from similar paintings found online; the image might be exquisitely rendered, but the person entering the prompt can’t claim credit for that.

Some commentators imagine that image generators will affect visual culture as much as the advent of photography once did. Although this might seem superficially plausible, the idea that photography is similar to generative A.I. deserves closer examination. When photography was first developed, I suspect it didn’t seem like an artistic medium because it wasn’t apparent that there were a lot of choices to be made; you just set up the camera and start the exposure. But over time people realized that there were a vast number of things you could do with cameras, and the artistry lies in the many choices that a photographer makes. It might not always be easy to articulate what the choices are, but when you compare an amateur’s photos to a professional’s, you can see the difference. So then the question becomes: Is there a similar opportunity to make a vast number of choices using a text-to-image generator? I think the answer is no. An artist—whether working digitally or with paint—implicitly makes far more decisions during the process of making a painting than would fit into a text prompt of a few hundred words.

We can imagine a text-to-image generator that, over the course of many sessions, lets you enter tens of thousands of words into its text box to enable extremely fine-grained control over the image you’re producing; this would be something analogous to Photoshop with a purely textual interface. I’d say that a person could use such a program and still deserve to be called an artist. The film director Bennett Miller has used DALL-E 2 to generate some very striking images that have been exhibited at the Gagosian gallery; to create them, he crafted detailed text prompts and then instructed DALL-E to revise and manipulate the generated images again and again. He generated more than a hundred thousand images to arrive at the twenty images in the exhibit. But he has said that he hasn’t been able to obtain comparable results on later releases of DALL-E . I suspect this might be because Miller was using DALL-E for something it’s not intended to do; it’s as if he hacked Microsoft Paint to make it behave like Photoshop, but as soon as a new version of Paint was released, his hacks stopped working. OpenAI probably isn’t trying to build a product to serve users like Miller, because a product that requires a user to work for months to create an image isn’t appealing to a wide audience. The company wants to offer a product that generates images with little effort.

It’s harder to imagine a program that, over many sessions, helps you write a good novel. This hypothetical writing program might require you to enter a hundred thousand words of prompts in order for it to generate an entirely different hundred thousand words that make up the novel you’re envisioning. It’s not clear to me what such a program would look like. Theoretically, if such a program existed, the user could perhaps deserve to be called the author. But, again, I don’t think companies like OpenAI want to create versions of ChatGPT that require just as much effort from users as writing a novel from scratch. The selling point of generative A.I. is that these programs generate vastly more than you put into them, and that is precisely what prevents them from being effective tools for artists.

The companies promoting generative-A.I. programs claim that they will unleash creativity. In essence, they are saying that art can be all inspiration and no perspiration—but these things cannot be easily separated. I’m not saying that art has to involve tedium. What I’m saying is that art requires making choices at every scale; the countless small-scale choices made during implementation are just as important to the final product as the few large-scale choices made during the conception. It is a mistake to equate “large-scale” with “important” when it comes to the choices made when creating art; the interrelationship between the large scale and the small scale is where the artistry lies.

Believing that inspiration outweighs everything else is, I suspect, a sign that someone is unfamiliar with the medium. I contend that this is true even if one’s goal is to create entertainment rather than high art. People often underestimate the effort required to entertain; a thriller novel may not live up to Kafka’s ideal of a book—an “axe for the frozen sea within us”—but it can still be as finely crafted as a Swiss watch. And an effective thriller is more than its premise or its plot. I doubt you could replace every sentence in a thriller with one that is semantically equivalent and have the resulting novel be as entertaining. This means that its sentences—and the small-scale choices they represent—help to determine the thriller’s effectiveness.

Many novelists have had the experience of being approached by someone convinced that they have a great idea for a novel, which they are willing to share in exchange for a fifty-fifty split of the proceeds. Such a person inadvertently reveals that they think formulating sentences is a nuisance rather than a fundamental part of storytelling in prose. Generative A.I. appeals to people who think they can express themselves in a medium without actually working in that medium. But the creators of traditional novels, paintings, and films are drawn to those art forms because they see the unique expressive potential that each medium affords. It is their eagerness to take full advantage of those potentialities that makes their work satisfying, whether as entertainment or as art.

Of course, most pieces of writing, whether articles or reports or e-mails, do not come with the expectation that they embody thousands of choices. In such cases, is there any harm in automating the task? Let me offer another generalization: any writing that deserves your attention as a reader is the result of effort expended by the person who wrote it. Effort during the writing process doesn’t guarantee the end product is worth reading, but worthwhile work cannot be made without it. The type of attention you pay when reading a personal e-mail is different from the type you pay when reading a business report, but in both cases it is only warranted when the writer put some thought into it.

Recently, Google aired a commercial during the Paris Olympics for Gemini, its competitor to OpenAI’s GPT-4 . The ad shows a father using Gemini to compose a fan letter, which his daughter will send to an Olympic athlete who inspires her. Google pulled the commercial after widespread backlash from viewers; a media professor called it “one of the most disturbing commercials I’ve ever seen.” It’s notable that people reacted this way, even though artistic creativity wasn’t the attribute being supplanted. No one expects a child’s fan letter to an athlete to be extraordinary; if the young girl had written the letter herself, it would likely have been indistinguishable from countless others. The significance of a child’s fan letter—both to the child who writes it and to the athlete who receives it—comes from its being heartfelt rather than from its being eloquent.

Many of us have sent store-bought greeting cards, knowing that it will be clear to the recipient that we didn’t compose the words ourselves. We don’t copy the words from a Hallmark card in our own handwriting, because that would feel dishonest. The programmer Simon Willison has described the training for large language models as “money laundering for copyrighted data,” which I find a useful way to think about the appeal of generative-A.I. programs: they let you engage in something like plagiarism, but there’s no guilt associated with it because it’s not clear even to you that you’re copying.

Some have claimed that large language models are not laundering the texts they’re trained on but, rather, learning from them, in the same way that human writers learn from the books they’ve read. But a large language model is not a writer; it’s not even a user of language. Language is, by definition, a system of communication, and it requires an intention to communicate. Your phone’s auto-complete may offer good suggestions or bad ones, but in neither case is it trying to say anything to you or the person you’re texting. The fact that ChatGPT can generate coherent sentences invites us to imagine that it understands language in a way that your phone’s auto-complete does not, but it has no more intention to communicate.

It is very easy to get ChatGPT to emit a series of words such as “I am happy to see you.” There are many things we don’t understand about how large language models work, but one thing we can be sure of is that ChatGPT is not happy to see you. A dog can communicate that it is happy to see you, and so can a prelinguistic child, even though both lack the capability to use words. ChatGPT feels nothing and desires nothing, and this lack of intention is why ChatGPT is not actually using language. What makes the words “I’m happy to see you” a linguistic utterance is not that the sequence of text tokens that it is made up of are well formed; what makes it a linguistic utterance is the intention to communicate something.

Because language comes so easily to us, it’s easy to forget that it lies on top of these other experiences of subjective feeling and of wanting to communicate that feeling. We’re tempted to project those experiences onto a large language model when it emits coherent sentences, but to do so is to fall prey to mimicry; it’s the same phenomenon as when butterflies evolve large dark spots on their wings that can fool birds into thinking they’re predators with big eyes. There is a context in which the dark spots are sufficient; birds are less likely to eat a butterfly that has them, and the butterfly doesn’t really care why it’s not being eaten, as long as it gets to live. But there is a big difference between a butterfly and a predator that poses a threat to a bird.

A person using generative A.I. to help them write might claim that they are drawing inspiration from the texts the model was trained on, but I would again argue that this differs from what we usually mean when we say one writer draws inspiration from another. Consider a college student who turns in a paper that consists solely of a five-page quotation from a book, stating that this quotation conveys exactly what she wanted to say, better than she could say it herself. Even if the student is completely candid with the instructor about what she’s done, it’s not accurate to say that she is drawing inspiration from the book she’s citing. The fact that a large language model can reword the quotation enough that the source is unidentifiable doesn’t change the fundamental nature of what’s going on.

As the linguist Emily M. Bender has noted, teachers don’t ask students to write essays because the world needs more student essays. The point of writing essays is to strengthen students’ critical-thinking skills; in the same way that lifting weights is useful no matter what sport an athlete plays, writing essays develops skills necessary for whatever job a college student will eventually get. Using ChatGPT to complete assignments is like bringing a forklift into the weight room; you will never improve your cognitive fitness that way.

Not all writing needs to be creative, or heartfelt, or even particularly good; sometimes it simply needs to exist. Such writing might support other goals, such as attracting views for advertising or satisfying bureaucratic requirements. When people are required to produce such text, we can hardly blame them for using whatever tools are available to accelerate the process. But is the world better off with more documents that have had minimal effort expended on them? It would be unrealistic to claim that if we refuse to use large language models, then the requirements to create low-quality text will disappear. However, I think it is inevitable that the more we use large language models to fulfill those requirements, the greater those requirements will eventually become. We are entering an era where someone might use a large language model to generate a document out of a bulleted list, and send it to a person who will use a large language model to condense that document into a bulleted list. Can anyone seriously argue that this is an improvement?