Liked to death? The social media race for nature photos can trash ecosystems – or trigger rapid extinction

Senior Lecturer in Wildlife Ecology, Edith Cowan University

Associate Professor, Behavioural Ecology, Curtin University

Adjunct Associate in Ornithology and Marine Ecology, Murdoch University

Disclosure statement

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Edith Cowan University , Curtin University , and Murdoch University provide funding as members of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

Have you ever liked or shared a social media post about nature? It could have been a photo of a rare orchid or an unusual bird. Or you might share a stunning photo of an “undiscovered” natural place.

It feels good to do so. You’re sharing something beautiful, an antidote to negativity. But not even this simple act is problem-free.

Social media have become a huge force. It’s come with many positives for nature, such as greater visibility and interest in citizen science and public knowledge about the species we share the planet with. Australia’s largest citizen science project, the Aussie Bird Count , collected reports of 3.6 million birds in backyards in one week, for example, making good use of social media.

There is, unfortunately, a dark side to this effortless sharing of information. It is possible to love species to death, as our new research has found.

How? Viral photos of undisturbed natural beauty can lead thousands of people to head there. As more people arrive, they begin destroying what they loved seeing on screen.

And then there’s the competitiveness among photographers and content-makers hoping to gain influence or visibility by posting natural content. Unethical techniques are common, such as playing the calls of rare bird species to lure them out for a photo.

Social media do not directly cause damage, of course. But the desire for positive feedback, visibility or income can be very strong incentives to act badly.

Can social media really damage species?

The critically endangered blue-crowned laughingthrush now lives in only one province in China. Its wild population is now around 300 .

So many people went to find and photograph this rare bird that the laughingthrush was forced to change how it nested to avoid flashlights and the sound of camera shutters.

Or consider bird call playback. For scientists, playing a bird’s calls is a vital tool. You can use calls to entice seabird colonies back to former nesting grounds or to monitor threatened or hard-to-spot species.

It’s very easy for birdwatchers and photographers to misuse this power by using bird ID apps and a speaker to draw out rare species. It might seem harmless, but drawing shy woodland birds out into the open risks predation, or can entice a mother off her nest. Playing calls can also make birds aggressive, change important behaviours, or disrupt their breeding.

Baiting, drones, poaching and trampling

The list of bad behaviours goes on and on.

Wildlife photographers are known to use baiting to get their photo – putting out food sources (natural or artificial), scent lures and decoys to boost their chances. But when baiting is done routinely, it changes animal behaviour. Baiting by tourist operators who offering swimming with sharks has led to reduced gene flow, changed shark metabolism and increased aggression.

Drone photography, too, comes with problems . Drones terrify many species of wildlife, causing them to break cover, try to escape or to become aggressive. In Western Australia, for instance, an osprey suffered injuries after a photographer flew their drone into it.

Then there are the world’s rare or fragile plants. Social media give us beautiful images of wildflower meadows and rainforests. But when we collectively go and see these places, we risk trampling them. Unlike animals, plants can’t run away.

Take orchids, a family of flowering plants with many human admirers. During the 18th century, “ orchidelerium ” gripped Europe. Rich people paid orchid hunters to roam the globe and collect rare species.

In our time, orchids face a different threat – social-media-driven visitors. Orchids are very particular – they rely on specific fungal partners . But this makes them highly vulnerable if their habitat changes. One study found that of 442 vulnerable orchid species, 40% were at risk from tourism and recreation.

Sharing locations is a big part of the problem. Even if you deliberately don’t make reference to where you took the photo, the GPS co-ordinates are often embedded in a photo’s metadata.

In 2010, a new species of slipper orchid ( Paphiopedilum canhii ) was discovered in Vietnam. Photos with location information were posted online. Just six months after discovery, more than 99% of all known individuals had been collected . The orchid is now extinct in the wild.

What should be done?

Broadly, we need to talk about the need to make ethical choices in how we present nature on social media.

But there is a specific group who can help – the admins of large social media groups devoted to, say, wild orchids, birdwatching or scuba diving. Admins have significant influence over what can be posted in their groups. Better moderation can go a long way.

Site admins can make expectations clear in their codes of conduct. They could, for instance, ban photos of rare orchids until after the flowering season, or put a blanket ban on posts with locations, as well as explain how photos can have embedded location data.

Park and land managers have other tools, such as banning drones from specific areas and making it harder to access environmentally sensitive areas. There’s a very good reason, for instance, why the location of wild populations of Wollemi pines is a secret .

Many of us won’t have given much thought about how social media can damage the natural world. But it is a real problem – and it won’t go away by itself.

Dr Belinda Davis from Western Australia’s Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions contributed to this article.

- Conservation

- Social media

- Environment

- Location data

- Wildlife photography

Service Delivery Consultant

Newsletter and Deputy Social Media Producer

College Director and Principal | Curtin College

Head of School: Engineering, Computer and Mathematical Sciences

Educational Designer

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

- Defence and armed forces

- Ministry of Defence estate

Work to save rare British moth from extinction in England

The rare dark bordered beauty moth exists at one last known site in England – a military training area near York.

A dark bordered beauty moth on a blade of grass.

The Ministry of Defence is working with partners to save the moth from extinction while continuing to use the site to conduct essential training to keep Britain safe.

The Ministry of Defence owns most of the moth’s English habitat, Strensall Common, which is a 570-hectare area of open heathland, designated a Site of Special Scientific Interest. Lying east of the North Yorkshire village of Strensall, in the Vale of York, the site is used for military training, with some areas managed by Yorkshire Wildlife Trust and Forestry England.

The small but striking moth is a priority species in the UK Biodiversity Action Plan. Numbers of the dark bordered beauty moth have declined by over 90% since recording first began at Strensall Common, with as little as 50 to 100 believed to remain at the site. The moth’s presence has been recorded at the common since 1894.

The moth favours sheltered locations at the woodland’s edges where its sole foodplant, creeping willow, can be found growing. Creeping willow habitats are threatened by factors such as wildfires and sheep grazing – leading to a steep decline in the moth’s population since systematic monitoring began in 2007.

Grazing of cattle and sheep on Strensall Common is essential to prevent the growth of trees and shrubs and maintain the site’s internationally important lowland heath habitats. However, grazing has caused the loss of creeping willow plants, meaning fewer good sites for the moth caterpillars to feed, and reduced opportunities for the moths to lay eggs in the summer.

To help save the moth from extinction in England, Defence Infrastructure Organisation (DIO) has provided funding and materials through its Conservation Stewardship Fund to create fenced enclosures around areas of low-growing creeping willow across the training area. Additional funding has been provided by Yorventure, an independent not-for-profit initiative supporting community and environmental projects in the City of York and North Yorkshire.

Defence Minister Luke Pollard said:

The first duty of any government is protecting our citizens, and I commend these conservation efforts to protect the wildlife that call our estate home and have no impact on our essential training activity. It’s brilliant to see the work we’re doing with partners to safeguard the survival of this wonderful moth while conducting training at the same site to keep Britain secure.

The work has been carried out by the Butterfly Conservation charity with the support of ecologists working for DIO, volunteers from the MOD Strensall Conservation Group, and experts from the University of York’s Department of Biology. Volunteers have also planted creeping willows grown from local seeds across Strensall Common to bolster habitats for the moth.

While these efforts have been instrumental in preventing the loss of the dark bordered beauty moth from Strensall Common, its population remains low and under threat. Conservationists are therefore considering trialling a captive breeding scheme to establish new populations of the moth in surrounding regions of York. This follows a recent project which saw the release of 160 dark bordered beauty moth caterpillars into a site in Scotland’s Cairngorm mountains, where the only other surviving populations of the moth in Britain can be found.

In the meantime, it is hoped that the continuing work to protect habitats for the dark bordered beauty moth at Strensall Common will ensure the site remains a stronghold for the species.

DIO Training Safety Officer and Chair of the MOD Strensall Conservation Group Major (Retired) Patrick Ennis said:

The Defence estate is home to some of the most valuable sites for nature and wildlife in the UK. While the primary use of the land is to enable our military to train, we are equally committed to supporting nature recovery by balancing the conservation of species and their habitats with military training requirements. The determined efforts of the MOD Strensall Conservation Group, Butterfly Conservation and local experts and volunteers have been key to preventing the dark bordered beauty from becoming extinct at its last known site in England, but unfortunately its numbers are still in decline. Continued collaboration will be essential in giving the moth the best chance of recovering its population.

Head of Conservation (England), Butterfly Conservation Dr Dave Wainwright said:

Despite ongoing conservation work by Butterfly Conservation, MOD and our partners, the dark bordered beauty remains at risk of extinction in England. It is crucial that our work to protect it at Strensall continues; at the same time, we need to restore suitable habitat elsewhere and enable the spread of the moth if its chances of survival are to be enhanced.

Dr Peter Mayhew from the University of York’s Department of Biology said:

The dark bordered beauty population at Strensall Common is of enormous cultural importance as it was the population where the moth was first discovered in the UK, and has been most frequently visited by entomologists interested in finding the moth. The moth has only survived thanks to the protection of the heathland provided by the military training area. Seeing the moth fly on a sunny morning is a never-to-be-forgotten experience which future generations deserve to enjoy.

The work being undertaken to protect the moth’s habitats is in line with the Government’s commitment to protect and restore nature and deliver the Environment Act targets.

Share this page

The following links open in a new tab

- Share on Facebook (opens in new tab)

- Share on Twitter (opens in new tab)

Updates to this page

Is this page useful.

- Yes this page is useful

- No this page is not useful

Help us improve GOV.UK

Don’t include personal or financial information like your National Insurance number or credit card details.

To help us improve GOV.UK, we’d like to know more about your visit today. Please fill in this survey (opens in a new tab) .

More From Forbes

A herpetologist spotlights the 4 ‘coolest’ extinct reptiles (hint: none are dinosaurs).

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Extinct species are every bit as interesting as those that are found in the wild today–perhaps ... [+] moreso. Here are four reptiles that would make your jaw drop if they had survived into the present-day.

The class of animals that we refer to as “reptiles” or “reptilia” came into existence in the late Carboniferous period, around 320 million years ago. At present, there are around 12,000 living species of reptiles (not counting birds, which are actually also part of the reptile lineage). However, there have been many more that have come and gone over the ages, the most famous of which are the dinosaurs which disappeared from Earth approximately 65 million years ago.

Setting dinosaurs aside, here are four species of ancient reptiles that get my vote for “best in class.”

Illustration of Titanoboa, a colossal prehistoric snake that live around 60 million years ago.

Titanoboa was a species of giant snake native to Columbia that was first documented in a 2009 paper published in Nature . It is thought to be the biggest snake to have ever existed, although a recent discovery in India challenges this assumption.

Regardless, the Titanoboa was absolutely massive, likely exceeding 40 feet in length and weighing over a ton. To put this in perspective, the largest snakes that exist on planet Earth today, the green anaconda and the reticulated python, measure around 30 feet in length and 600 pounds at their biggest.

Titanoboa inhabited the warm, tropical environment of what is now northern Colombia. As a top predator of its time, Titanoboa would have preyed upon a variety of large vertebrates, employing its powerful constricting abilities akin to modern boa constrictors. Fossil evidence suggests that the snake lived approximately 60 million years ago, during the early part of the Paleogene period.

Best High-Yield Savings Accounts Of 2024

Best 5% interest savings accounts of 2024.

Tylosaurus, an extinct genus of mosasaur lizards. These giant predatory marine lizards roamed the ... [+] seas until 66 million years ago, coexisting with dinosaurs.

The ancient mosasaur, a giant marine lizard, was a formidable predator that thrived during the late Cretaceous period, approximately 100 to 66 million years ago. These colossal reptiles, belonging to the reptile lineage Mosasauria, were characterized by their elongated, streamlined bodies, powerful tails and paddle-like limbs, which made them highly efficient swimmers. The are closely related to modern day lizards and snakes.

Mosasaurs grew up to an impressive 50 feet in length, similar to a humpback whale although not weighing as much. Their large, conical teeth and strong jaws allowed them to prey on a variety of marine life, including fish, squid, molluscs and even other marine reptiles. As apex predators in their aquatic ecosystems, mosasaurs dominated the seas until their extinction at the end of the Cretaceous period, coinciding with the mass extinction event that wiped out the dinosaurs.

Meiolania, an extinct genus of giant, armored turtles native to Australasia from the Middle Miocene ... [+] until relatively recently.

Meiolania was a remarkable genus of prehistoric turtles that lived from the mid-Miocene (10-20 million years ago) until a few thousand years ago. Native to Australasia, Meiolania was notable for its large size and distinctive physical features. Unlike most modern turtles, they had a robust, armored shell and some species exhibited prominent, horn-like projections on their head and a large, spiked club-like structure at the end of their tail, which is believed to have been used for defense against predators. This formidable appearance suggests that Meiolania was a heavily armored herbivore that spent much of its time on land.

When exactly Meiolania went extinct is a subject of debate in scientific circles. Some scholars believe that rising sea levels following the retreat of the last ice age (12,000 years ago) led to their demise by reducing the land they inhabited (many Pacific islands were swallowed by the sea during this time). However, another theory suggests that megafaunal turtles like Meiolania lived alongside humans before going extinct–and that hunting by humans may have precipitated their demise. This is based on fossil evidence showing that Meiolania remains were layered above human remains in graveyard sites on islands such as Vanuatu and Fiji. In fact, the Meiolania bones found at the sites show evidence of being cut up and consumed.

Model of Gigarcanum delcourti, a recently extinct giant gecko most likely originating from the ... [+] island of New Caledonia.

Gigarcanum delcourti is an extinct species of giant gecko that inhabited either New Caledonia or New Zealand possibly up to the mid-19th century. It is the largest known gecko species, at least 2 feet in length, estimated to be 50% longer and substantially heavier than the largest extant gecko, New Caledonia’s Rhacodactylus leachianus commonly known as Leach’s giant gecko.

Interestingly, the species is known by one taxidermied specimen, which was collected in the 19th century and later rediscovered unlabelled in the basement of a museum in France. The specimen’s origin was not documented. Although it was initially believed to be from New Zealand, ancient DNA analysis has revealed that it most likely originates from New Caledonia.

- Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

Join The Conversation

One Community. Many Voices. Create a free account to share your thoughts.

Forbes Community Guidelines

Our community is about connecting people through open and thoughtful conversations. We want our readers to share their views and exchange ideas and facts in a safe space.

In order to do so, please follow the posting rules in our site's Terms of Service. We've summarized some of those key rules below. Simply put, keep it civil.

Your post will be rejected if we notice that it seems to contain:

- False or intentionally out-of-context or misleading information

- Insults, profanity, incoherent, obscene or inflammatory language or threats of any kind

- Attacks on the identity of other commenters or the article's author

- Content that otherwise violates our site's terms.

User accounts will be blocked if we notice or believe that users are engaged in:

- Continuous attempts to re-post comments that have been previously moderated/rejected

- Racist, sexist, homophobic or other discriminatory comments

- Attempts or tactics that put the site security at risk

- Actions that otherwise violate our site's terms.

So, how can you be a power user?

- Stay on topic and share your insights

- Feel free to be clear and thoughtful to get your point across

- ‘Like’ or ‘Dislike’ to show your point of view.

- Protect your community.

- Use the report tool to alert us when someone breaks the rules.

Thanks for reading our community guidelines. Please read the full list of posting rules found in our site's Terms of Service.

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Auto Racing

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Wetland plant once nearly extinct may have recovered enough to come off the endangered species list

In this September 2020 photo provided by Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, a northeastern bulrush stands in a vernal pool in Tioga State Forest in Tioga County, Pa. The plant was in danger of extinction but recovery efforts have led the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to propose that it be removed from the federal endangered species list. (Mary Ann Furedi/Western Pennsylvania Conservancy via AP)

- Copy Link copied

BOSTON (AP) — The federal wildlife service on Tuesday proposed that a wetland plant once in danger of going extinct be taken off the endangered species list due to its successful recovery.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is asking that the northeastern bulrush be delisted . The plant is a leafy perennial herb with a cluster of flowers found in the Northeast from Vermont to Virginia. The federal service’s proposal opens a 60 day comment period.

The plant was listed as endangered in 1991 when there were only 13 known populations left in seven states. It now has 148 populations in eight states, often in vernal pools, swamps and small wetlands.

“Our important partnerships with state agencies, conservation organizations and academic researchers have helped us better understand and conserve northeastern bulrush through long-term population monitoring, habitat conservation, and increased surveys in prime habitat areas,” said Wendi Weber, northeast regional director for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Detailed surveys of the plant’s unique behavior have aided the recovery effort. The bulrush can disappear for years and reemerge when conditions are right.

Several states also worked to reduce invasive species that encroach on wetlands and protect land where the bulrush is found. Vermont, for example, has purchased two parcels for the bulrush.

In 2014, a coalition of soil and water conservation groups and a wetlands organization launched a successful pilot program to establish a new northeastern bulrush population in New York.

The Spinoff

Society about 11 hours ago

The spinoff essay: following the swiss wolf, who walked 2,000 kilometres for love.

- Share Story

When we insert ourselves into the lives of animals, we become complicit in their fates.

The Spinoff Essay showcases the best essayists in Aotearoa, on topics big and small. Made possible by the generous support of our members.

B efore I went to Hungary, I met a man who told me about the wolf.

“It migrated all the way from Switzerland to Hungary,” he said. “And last week it was shot by a hunter. People want him to go to prison.”

As I prepared for the trip I learnt more about M237, the wolf who’d travelled a record-breaking 2,000 km before being felled by a bullet near the small town of Hidasnémeti. But my real focus was on another mammal: my diabetic cat, Jager. At 17, her life was constrained to an armchair with a heating pad she reached with the assistance of pet steps. As my departure loomed, so did Jager’s. I rang a vet who offered a home euthanasia service and sought her advice.

“When it’s time for her to go, you’ll know,” she said.

But I didn’t know. I didn’t know if Jager would make it through the next four weeks without me. Our younger cat, Bruce, would be fine at home. I wrote instructions for his pet sitter and stockpiled his favourite treats. And then I took Jager to the best cattery in Dunedin, boarded a plane, and crossed my fingers.

Jager and M237 both began their lives wild, but while Jager assumed the role of house cat, M237 became an explorer. One of six cubs, he was born in 2021 as tulips bloomed and boats cruised the Swiss Riviera. At around two weeks of age, his blue eyes opened and he gave his first high-pitched howl. Soon afterwards, he ventured from his den on stubby legs, round-eyed and fluffy as a Pomeranian.

By March the following year, his legs were long, his eyes pale gold – and he was about to have his first encounter with humans. While skiers slid down the Swiss Alps, M237 was trapped and sedated by members of a Swiss wolf protection group. His blood was drawn, his teeth examined, and his body measured. And then he was fitted with the yellow GPS collar that helped make him a star.

No wolves wander New Zealand: our native mammals are bats, seals, sea lions, dolphins and whales. We no longer have wolves in our zoos, but they still filled my suburban Christchurch childhood. They were there in the stories of Peter and the Wolf, The Boy Who Cried Wolf, and Little Red Riding Hood. They roamed my imagination as metaphors for fear. Fear of being harmed. Fear of losing what’s precious.

Leaving New Zealand, my fears were personal, cat-sized. Arriving in Hungary in June 2023, my fears grew. Russian forces had taken control of the adjacent Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia power plant and 8.2 million Ukrainians had fled their country. I didn’t want to be on the continent if fighting escalated. But Europe’s a big place, I told myself. And if the worst happened, my husband Tim and I could flee to the safety of our island at the bottom of the South Pacific.

My worries vaporised when we arrived in stinking hot, beautiful Budapest. We visited galleries, saw a ballet, and sampled raspberry ganache beneath gilded frescoes.

We caught a train south to the city of Pécs, far from the Ukrainian border, where I was being hosted for a writing residency. Coloured tiles sparkled on rooftops, live music tinkled down laneways, and pigeons cooed outside our windows as we tossed and turned beneath our individual duvets, struggling to adjust to the heat. But my social media feeds were filled with images of snow. I sent an email to Jager’s cattery.

“Is her heating pad on?” I asked. “Did you get a chance to move her into the room with the sun?”

Reassured she’d settled in and was receiving her medication, I turned my attention back to M237. I started to wonder if I should visit northern Hungary after all; if I should visit Hidasnémeti. And I wasn’t the only person who wanted to acknowledge M237: there were 53,099 signatures on a petition calling for the hunter to be punished.

“Let us not be a country without consequences,” it read. “ A man who knowingly kills a great animal should not get away with impunity. Feel the weight of what you do.”

I met Károly Méhes, the coordinator of the residency programme. We sipped coffee on an ancient street in 35-degree heat, and I told him about my plans to go north. Then he surprised me by telling me Pécs has its own history with wolves.

“Like in the fairy tale, a wolf tore apart a grandmother and a grandchild,” he said.

The attack happened in December 1995, just after Christmas, while children were sledding on the Mecsek Mountains by the Pécs Zoo. At that time, the zoo was poorly run and prone to scandal. There was a period when a lion drowned, a tiger disappeared from the inventory, and the zoo’s director let hunters shoot a bear. In these chaotic conditions, it’s suspected the wolf was accidentally released. A passing driver saw a boy bleeding as he fled through the snow, and drove him to the TV tower to get help. The grandmother died on her way to hospital. The wolf was shot.

I decided to follow in the footsteps of the wolf, the grandmother and the boy, hiking up to the zoo and the tower. Noting that without his navigational services I’d still be lost in Singapore Airport, Tim came along too.

The Hungarian forest was different to the bush back home. The trees were thinner and further apart, and didn’t have the damp, fresh scent I’m used to. Sunlight streamed through the canopy, and we passed a cottage in a clearing bordered by a low stone fence. These were the woods I’d read about in fairy tales.

“If one of us – perhaps you – could get bitten by a wolf, it would be great for my story,” I said, as we trudged through the trees. Something rustled in the undergrowth and Tim sprang back.

We reached the top of a track and found ourselves at the zoo. From the outside, we could see zebras, bison, and hordes of small children – but no wolves. There are no longer wolves at Pécs Zoo. They were shipped off after the second wolf escaped.

By 2015, Pécs Zoo had a new director. Three wolves were acquired from Italy, but spooked by the move, one of them jumped the fence. People were advised to avoid the forest – but instead, they flocked to it.

“I think we all knew the nature of the animal, that it does not attack people, in fact it avoids it,” one wolf-watcher wrote. “He looked kindly at us and we looked at him.”

This wolf may have been harmless to humans, but he too was shot – by the zoo’s new director.

Today the zoo has yet another director, and the fencing still looks a little flimsy. We hiked past and dipped back into the woods as we continued to the tower. We spotted black and yellow moths, emerald green beetles and orange-stemmed mushrooms with puffy white hats. We didn’t see the badgers, foxes or dormice we knew lived in the forest. And with no wolves in Pécs, our biggest fear was getting lost. But when we returned to our apartment, there was a message from one of my brothers.

“It could be worth keeping an eye on the Zaporizhzhia power plant the Russians are said to have mined,” it read. “I’d advise you to have some sort of contingency plan and to act upon it promptly if something blows up.”

We’d already planned our trip to Hidasnémeti. I wanted to visit the river where M237 was shot. Making the most of travelling to the Zemplén region, Tim eschewed Hidasnémeti’s sole accommodation option – the former Border Guard Barracks – and booked us into the Palace Hotel in Lillafüred, a nearby resort town.

I spent the night before we left measuring Lillafüred’s distance from the fighting in Ukraine. We’d be staying an hour’s drive from the border – close enough to have me searching for tips on surviving a nuclear blast. What I read wasn’t reassuring. In the event of a power plant explosion, an invisible radioactive cloud could drift anywhere on the continent.

Like radioactive clouds, wolves aren’t concerned with the demarcation of human territory. The previous summer, M237 left his family and the canton of Graubünden in search of a mate. He reached an altitude of 3,500m as he travelled the Alps, his collar pinging his location to the enthusiasts tracking his path.

He crossed the Italian border, wandering beneath limestone summits before entering Austria. In February 2023, he slipped into Hungary. He passed just west of Budapest, and swam across the Danube before continuing towards the Zemplén Mountains.

The Swiss wolf protection group posted a Facebook update, tagging themselves as “feeling awesome”. Having M237 join Hungary’s small wolf population was a rare environmental success story. And there was something else about his journey that touched our hearts. Don’t we all feel we’ve been on epic quests in search of love?

M 237 was right to head to Zemplén for romance. Nestled in lush forest, the Palace Hotel felt enchanted. Swallows circled the spires, poetry was inscribed on stone tablets, and hanging gardens followed the path of a waterfall. In the Romanesque castle at the meeting of three valleys, I felt more relaxed than I’d been in years.

Not far from Lillafüred was the zoo where the Pécs wolves now lived. But though I longed to set eyes on a wolf, I didn’t want to visit a zoo – my entry fee endorsing the keeping of animals in captivity. Putting myself in a wolf’s paws, I would rather roam free. Instead, I visited the zoo’s website, my fingers hovering over the button that would enable me to “adopt” a wolf for a fee. But when we insert ourselves into the lives of animals, we become complicit in their fates. I shut the window.

The next morning, we caught a tram through the city of Miskolc and a train to Hidasnémeti’s small, Soviet-era station. From there we headed to the river, where I imagined M237 padding through the undergrowth to drink the cool water.

We passed a headstone maker’s workshop and saw bright cottage gardens alive with cats. Having learnt that wolves avoid people, I didn’t think I’d feel nervous for my safety if there was a wolf in my neighbourhood. But I would feel nervous for my pets.

Along with tracking M237, I’d been tracking Dávid Sütő, Large Carnivore Programme Leader at the World Wildlife Foundation. I wanted to ask him about wolves – in particular, M237, who Dávid called “the Swiss wolf”.

“I mainly deal with human-wildlife conflicts,” Dávid said, when we connected over Zoom. “Surrounding large carnivores there can be challenges, because they were missing from almost the whole continent for at least 50 years. We have to relearn how to live with them.”

Humans almost drove large predators to extinction a century ago, but the presence of wolves helps balance the ecosystem.

“We call them the guards of the forest. You need apex predators to keep invasive species like racoons at bay.”

Because wolves tend to prey on sick animals, they can also reduce the spread of disease. But not everyone’s happy that the wolves are returning to the forests.

“Knowing that wolves are present can cause fear in people, but wolves are not as dangerous as we think. In Northern Hungary, you’re much more likely to get hurt driving a car than you are to be mauled by a wolf.”

“What about the Pécs attack?” I asked.

“That was the only wolf attack in the country in the last hundred years, and it wasn’t a wild wolf,” Dávid said. “The wild specimens that have lived in nature have not attacked anyone, and it is crucial to try to keep it this way.”

Before we ended the call, I asked Dávid what had drawn him to his role.

“I’ve always dealt with mammals,” he said. “Because we are mammals too, we have some kind of kinship with them. It’s easier to get in their understanding.”

O n our last morning in The Palace Hotel, I woke with the sun. I stretched lazily on white sheets, wondering how on earth I’d got so lucky. And then I checked my phone. There was an email from the cattery.

“I have some sad news,” the message read. “Your lovely Jager passed away.”

My fears of radioactive clouds suddenly seemed ludicrous. The worst had happened, and it was the lonely death of someone who’d trusted me. I regretted not organising that visit from the vet. I regretted going on the trip at all.

We began our comically awful trip back to Pécs. As we were pelted with rain, thrown off a tram, issued with a fine, and confined to a stifling train carriage with drunken revellers, I thought about what we owe to animals. What I owed Jager, and what we all owed M237.

Like cats, wolves can get diabetes, but a sick animal won’t last long in the wild. Jager had been on insulin for the final two years of her life. Bruce, who I found on the side of the road as a kitten, had already had several hair-raising trips to the vet.

Cats aren’t considered domesticated: they have a symbiotic relationship with us. When I’d invited the cats into my home, I’d made a contract with them. I’d give them food, shelter, medical care and love, and I’d also have to make decisions on their behalf – decisions they wouldn’t always understand, or enjoy. But my cats could also choose to leave at any time.

What kind of contract had we made with the animals of Pécs Zoo? Could they have reasonably expected a standard of care they didn’t get? And what did we owe M237? Not medicine, or a heating pad, or a lap to die on. But not a bullet.

“When The Swiss Wolf was shot, there was an outrage,” Dávid had said. “In Hungary, the carnivores are strictly protected. And where he was shot, we have had wolves since the 1990s. So, the hunter could have expected that they were aiming at a wolf.”

And of course, the wolf was wearing a big, yellow GPS collar. But Dávid said it can be hard to investigate these types of cases.

“In a forest there are no witnesses. It’s ‘shoot, shovel, and shut up.’”

Europe has a long cultural history of humans and other apex predators sharing a landscape, but the survival of wolves in Hungary now depends on our ability to let the animals be. Wolves face enough danger without us: injury, starvation, and the possibility of being killed by a car, train, or group of rival wolves. M237 was willing to risk it all to find a mate.

“If the Swiss wolf had met a pack with a young female, they might have formed their own pack,” Dávid said.

When he was shot, M237 was 5km from a national park and the wolves of Zemplén. Had he picked up the scent of a potential mate? And had she picked up his?

D eath followed us back to Pécs. Catching up on New Zealand news, I saw that a critically endangered matuku-hūrepo had to be euthanised after being illegally shot. And in Europe, Ukrainian writer Victoria Amelina had died after being wounded in a Russian missile attack, just as she prepared to begin a residency in Paris.

And I was increasingly worried about Bruce. I contacted our pet sitter, trying not to sound hysterical.

“Is Bruce doing OK?”

“He seems to be all good and is eating,” came the reply.

But two mornings later when I woke and checked my phone, the pet sitter had left several missed calls. I called back and over a bad line heard “euthanasia”. Tim and I scrambled to add credit to our phones. We rang the vet and learnt Bruce had been badly bitten. The wound was infected, his flesh was necrotic, and he had sepsis. If he made it through the night, he’d face an operation he might not survive.

I felt sick. Being home wouldn’t have prevented the bite – but because I know Bruce, because I’m in his understanding, I would have realised something was wrong sooner. We were almost due to return home, and bringing our flights forward would cost $5,000. All I could do for Bruce was send positive thoughts from the other side of the world, hoping I was tuning into the right wavelength.

At around 1am, we got an email.

“We went ahead with tissue debridement this morning – cutting away the necrotic pieces of skin, of which there was a lot. There was a significant amount of dead tissue on both sides where he was bitten – most likely by a dog.”

You’re much more likely to be injured by a dog than a wolf, even in Northern Hungary. And in Dunedin, there’s a dog in our neighbourhood that often roams wild. I wanted its owners to see Bruce. Feel his pain.

At last, we returned to Dunedin to face a reckoning of our own. We collected Jager’s body and dug her grave. We picked Bruce up from the vet, knowing he’d be forever changed. And I felt the weight of what I’d done.

Ancient 'hobbits' were even smaller than previously thought, scientists say

Scientists studying ancient cousins of humans have big news: A hobbit-like species was even smaller than previously thought.

Fossils of Homo floresiensis (dubbed "hobbits" for their resemblance to the fictional Middle-earth dwellers in the "Lord of the Rings" books) were first discovered in 2003. Those fossils showed they lived 50,000 to 100,000 years ago on the Indonesian island of Flores, east of Bali. Flores is about the size of Puerto Rico.

Now, even older fossils from 700,000 years ago show that an early human species was likely about 2½ inches smaller than their later ancestors. Both are believed to have evolved from an older, taller species called Homo erectus.

The archaic humans, a now-extinct cousin to modern humans, were slightly shorter than the average human 4-year-old. The later hobbits were believed to be about 3 feet 6 inches tall. The older fossils show their predecessors could have been as short as 3 feet 3 inches.

"With this discovery, we found they were even smaller than we thought, so it was quite shocking to me," said Yousuke Kaifu, a professor of anthropology at the University of Tokyo and first author of the paper , published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications.

The original research, from a team of Indonesian and Australian archeologists, was first published in 2004 and stunned the world . It was led by renowned Australian archeologist Michael John Morwood .

Those first fossils were found in Liang Bua cave . The much older fossils Kaifu and others have studied came from another site on the island called Mata Menge and help confirm research first published in 2016 showing the older hobbits could have been even shorter than the later ones.

This week's paper is based on fragments of an upper arm bone and teeth from the same areas of Mata Menge, which Kaifu's Japanese-Australian team has been studying carefully ever since.

"It took a long time to have data that was convincing," he said.

'Strange evolution' created hobbits

Kaifu and others believe this particular species of human evolved from Homo erectus, another extinct human species that lived about 2 million years ago. Homo erectus means "upright human" because the species walked upright.

"We know Homo erectus was on the island of Java 1.1 million years ago. Somehow they crossed the ocean and reached these islands and became isolated – and then they experienced a strange evolution," Kaifu said.

Sometime between 1.1 million years ago and 600,000 years ago, the Homo erectus people on the island of Flores evolved into hobbits. Then they maintained their body size and survived for at least 500,000 years.

The nearest island is about 6 miles across treacherous seas, so how they got there isn't known.

As to where they went, no one knows. They seem to have vanished from the island about 50,000 years ago . That might or might not , have been around the time modern-day humans first arrived.

One thing that isn't mysterious: why the early cousins of humans shrunk as they inhabited the island of Flores.

It's well-documented that animals on islands lacking predators can very quickly evolve much smaller forms, a process called phyletic dwarfism. It has been known to happen with deer, cattle, elephants, hippopotami and other species. It can also happen quickly.

In one example that started in 1871, feral cattle on Amsterdam Island in the southern Indian Ocean shrank to about three-quarters of their original body size in slightly more than a century.

In the case of the hobbits, Kaifu believes they quickly evolved to be smaller because there was nothing on the island that would have specifically hunted them.

"Without predators, there's no advantage to being large because you don't have to fight anything off," he said. "To maintain a larger body size you have to eat a lot; it takes more time to grow and produce offspring. So smaller body size is more productive."

Though the hobbits didn't face predators, they still had to deal with the island's Komodo dragons and giant stork-like birds that stood almost 6 feet tall. "These were a big stress for them – they must have been intelligent," Kaifu said.

Small-brained as they were, the hobbits used stone tools and appear to have hunted some of the other dwarf animals on the island, including a mini elephant species called dwarf stegodons about the size of modern buffalo. The hobbits may also have used fire .

The hobbits aren't the only now-extinct tiny cousins to humans. In 2019, archeologists announced the discovery of another diminutive human species whose fossils were found in Callao Cave on the island of Luzon in the Philippines. Called Homo luzonensis , the species lived on the island 50,000 to 76,000 years ago.

Essay on Extinct Animals

Students are often asked to write an essay on Extinct Animals in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Extinct Animals

What are extinct animals.

Extinct animals are species that don’t exist anymore. They vanished forever due to various reasons like habitat loss, hunting, or climate change.

Examples of Extinct Animals

Famous extinct animals include the Dodo, a bird from Mauritius, and the Tasmanian Tiger, a carnivorous marsupial from Australia.

Why Animals Become Extinct

Animals become extinct mainly due to human activities. Deforestation, pollution, and overhunting are major causes.

Importance of Preventing Extinction

Preventing extinction is crucial for biodiversity. Each species plays a role in the ecosystem, and their loss can disrupt the balance.

250 Words Essay on Extinct Animals

Introduction, the causes of extinction.

The primary causes of animal extinction include habitat loss, climate change, overexploitation, and invasive species. The relentless expansion of human civilization often leads to habitat destruction, leaving animals without homes or food sources. Climate change disrupts the delicate balance of ecosystems, making survival difficult for many species. Overhunting and overfishing have also led to the extinction of numerous species. Lastly, invasive species, introduced either intentionally or accidentally, can outcompete native species for resources, leading to their extinction.

Impact on Biodiversity

The extinction of animals greatly affects biodiversity. Each species plays a unique role within its ecosystem, and its loss can disrupt the balance, leading to cascading effects on other species. For instance, the extinction of a predator can lead to overpopulation of its prey, which may then overconsume vegetation and disrupt the ecosystem.

Conservation Efforts

Conservation efforts are crucial to prevent further extinctions. These include habitat protection, regulation of hunting and fishing, and breeding programs for endangered species. Additionally, raising public awareness about the importance of biodiversity and the consequences of extinction can drive societal changes necessary for conservation.

In conclusion, the extinction of animals is a pressing issue that requires immediate attention. Through understanding its causes and impacts, and implementing effective conservation strategies, we can hope to preserve the remaining biodiversity for future generations.

500 Words Essay on Extinct Animals

The natural world is a vast, interconnected web of life, with each species playing a unique role in the balance of the ecosystem. However, in recent centuries, human activities have greatly accelerated the rate of animal extinction, leading to a loss of biodiversity. This essay will delve into the topic of extinct animals, exploring the causes and consequences of extinction, and the importance of conservation efforts.

The Consequences of Extinction

The extinction of animals has far-reaching implications. Firstly, it disrupts the balance of ecosystems. Each species plays a unique role in its ecosystem, and the loss of a single species can trigger a cascade of changes that affect other species. Secondly, extinction can lead to the loss of genetic diversity, which is crucial for the resilience of ecosystems in the face of environmental changes. Thirdly, the extinction of animals can have economic implications, affecting industries such as tourism and agriculture that rely on biodiversity.

Extinct Animals: A Case Study

The dodo bird, native to Mauritius, serves as a poignant example of human-induced extinction. Unaccustomed to predators, these birds were easy prey for humans and invasive species introduced by sailors in the 17th century. Their extinction within less than a century of their discovery highlights the devastating impact of human activities on biodiversity.

The Importance of Conservation

In conclusion, the extinction of animals is a pressing issue that has been largely driven by human activities. The loss of species has profound implications for ecosystems and human societies. Therefore, it is imperative that we intensify our conservation efforts to protect biodiversity. The fate of many species lies in our hands, and it is our responsibility to ensure that they do not go the way of the dodo.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- IELTS Scores

- Life Skills Test

- Find a Test Centre

- Alternatives to IELTS

- General Training

- Academic Word List

- Topic Vocabulary

- Collocation

- Phrasal Verbs

- Writing eBooks

- Reading eBook

- All eBooks & Courses

- Sample Essays

Extinction of Animals Essay

This extinction of animals essay question appeared recently in the IELTS test.

It is about how animals become extinct and whether humans should take steps to prevent this from happening.

It is a natural process that animal species become extinct, as the dinosaurs did in the past. There is no reason for people to prevent this from happening.

To what extent do you agree or disagree?

Choosing a Side

With agree / disagree type essays you can discuss both sides of the issue but you can come down firmly on one side and focus on only this in your response.

This can be an easier way to answer such questions and is certainly recommended if you are just needing the lower band scores, such as 7 and especially 6.

This is an example of an essay where the writer disagrees with the opinion and has given three reasons for this, set out in three body paragraphs.

For the higher band scores there is a risk the examiner thinks for a fully addressed answer , both sides of the issue should have been considered. So if you need a band 8 or 9, look at both sides of the issue as in this model answer.

Take a look at the model answer for this animal extinction essay and the comments below.

Extinction of Animals Essay Sample

You should spend about 40 minutes on this task.

Write about the following topic:

Give reasons for your answer and include any relevant examples from your own experience or knowledge.

Write at least 250 words.

Model Answer

It is commonly known that many species have gone extinct throughout history, including the dinosaurs. Some argue that preventing extinction is not necessary, as it is a natural process. However, I believe that humans have a moral obligation to protect endangered species and prevent their extinction.

Firstly, human activities such as deforestation, overfishing, and pollution have caused a rapid decline in animal populations, leading many species to be at risk of extinction. As a result, humans have a responsibility to conserve the environment and prevent further harm to wildlife. It is unfair for humans to cause the extinction of a species due to their actions, particularly when they have the ability to prevent it.

Another reason is that many species play a crucial role in maintaining the balance of the ecosystem. For example, bees are essential pollinators that are responsible for pollinating 80% of flowering plants, and thus if bees were to become extinct, it would have a devastating impact on our food supply and ecosystem. Similarly, the loss of predators can cause a ripple effect, leading to overpopulation of other species and causing imbalances in the food chain.

Lastly, preventing extinction is not only a matter of responsibility but also a matter of morality. Species have intrinsic value, and it is not our place to determine which species should exist and which should not. Humans must respect the inherent value of all life forms and do what they can to protect them.

In conclusion, while extinction may be a natural process, it is not a justification for humans to sit idly by and watch as countless species go extinct. By taking action to conserve the environment, humans can ensure that future generations can enjoy the same diversity of life that we have today.

(294 Words)

This extinction of animals essay would achieve a high IELTS band score.

It's organised well so would score highly for coherence and cohesion . It has a clear introduction that introduces the topics and then gives the writers opinion (the thesis statement).

Each body paragraph clearly sets out and explains a key idea, then the conclusion summarises the writers view and gives some final thoughts. The linking between sentences is also very good.

It has a clear opinion and that opinion is reflected in the response. The ideas are fully supported and explained. The question is fully addressed and the essay does not go off-topic. It would therefore score highly for task response .

The essay also had a good range of high-level and accurate lexis and grammar , so it would also score well for those criteria.

<<< Back

Next >>>

More Agree / Disagree Essays:

Paying Taxes Essay: Should people keep all the money they earn?

Paying Taxes Essay: Read model essays to help you improve your IELTS Writing Score for Task 2. In this essay you have to decide whether you agree or disagree with the opinion that everyone should be able to keep their money rather than paying money to the government.

Multinational Organisations and Culture Essay

Multinational Organisations and Culture Essay: Improve you score for IELTS Essay writing by studying model essays. This Essay is about the extent to which working for a multinational organisation help you to understand other cultures.

IELTS Vegetarianism Essay: Should we all be vegetarian to be healthy?

Vegetarianism Essay for IELTS: In this vegetarianism essay, the candidate disagrees with the statement, and is thus arguing that everyone does not need to be a vegetarian.

Ban Smoking in Public Places Essay: Should the government ban it?

Ban smoking in public places essay: The sample answer shows you how you can present the opposing argument first, that is not your opinion, and then present your opinion in the following paragraph.

Essay for IELTS: Are some advertising methods unethical?

This is an agree / disagree type question. Your options are: 1. Agree 100% 2. Disagree 100% 3. Partly agree. In the answer below, the writer agrees 100% with the opinion. There is an analysis of the answer.

Examinations Essay: Formal Examinations or Continual Assessment?

Examinations Essay: This IELTS model essay deals with the issue of whether it is better to have formal examinations to assess student’s performance or continual assessment during term time such as course work and projects.

Internet vs Newspaper Essay: Which will be the best source of news?

A recent topic to write about in the IELTS exam was an Internet vs Newspaper Essay. The question was: Although more and more people read news on the internet, newspapers will remain the most important source of news. To what extent do you agree or disagree?

IELTS Sample Essay: Is alternative medicine ineffective & dangerous?

IELTS sample essay about alternative and conventional medicine - this shows you how to present a well-balanced argument. When you are asked whether you agree (or disagree), you can look at both sides of the argument if you want.

Sample IELTS Writing: Is spending on the Arts a waste of money?

Sample IELTS Writing: A common topic in IELTS is whether you think it is a good idea for government money to be spent on the arts. i.e. the visual arts, literary and the performing arts, or whether it should be spent elsewhere, usually on other public services.

Return of Historical Objects and Artefacts Essay

This essay discusses the topic of returning historical objects and artefacts to their country of origin. It's an agree/disagree type IELTS question.

Technology Development Essay: Are earlier developments the best?

This technology development essay shows you a complex IELTS essay question that is easily misunderstood. There are tips on how to approach IELTS essay questions

Scientific Research Essay: Who should be responsible for its funding?

Scientific research essay model answer for Task 2 of the test. For this essay, you need to discuss whether the funding and controlling of scientific research should be the responsibility of the government or private organizations.

Dying Languages Essay: Is a world with fewer languages a good thing?

Dying languages essays have appeared in IELTS on several occasions, an issue related to the spread of globalisation. Check out a sample question and model answer.

Truthfulness in Relationships Essay: How important is it?

This truthfulness in relationships essay for IELTS is an agree / disagree type essay. You need to decide if it's the most important factor.

Human Cloning Essay: Should we be scared of cloning humans?

Human cloning essay - this is on the topic of cloning humans to use their body parts. You are asked if you agree with human cloning to use their body parts, and what reservations (concerns) you have.

Employing Older People Essay: Is the modern workplace suitable?

Employing Older People Essay. Examine model essays for IELTS Task 2 to improve your score. This essay tackles the issue of whether it it better for employers to hire younger staff rather than those who are older.

Free University Education Essay: Should it be paid for or free?

Free university education Model IELTS essay. Learn how to write high-scoring IELTS essays. The issue of free university education is an essay topic that comes up in the IELTS test. This essay therefore provides you with some of the key arguments about this topic.

Airline Tax Essay: Would taxing air travel reduce pollution?

Airline Tax Essay for IELTS. Practice an agree and disagree essay on the topic of taxing airlines to reduce low-cost air traffic. You are asked to decide if you agree or disagree with taxing airlines in order to reduce the problems caused.

IELTS Internet Essay: Is the internet damaging social interaction?

Internet Essay for IELTS on the topic of the Internet and social interaction. Included is a model answer. The IELTS test usually focuses on topical issues. You have to discuss if you think that the Internet is damaging social interaction.

Role of Schools Essay: How should schools help children develop?

This role of schools essay for IELTS is an agree disagree type essay where you have to discuss how schools should help children to develop.

Any comments or questions about this page or about IELTS? Post them here. Your email will not be published or shared.

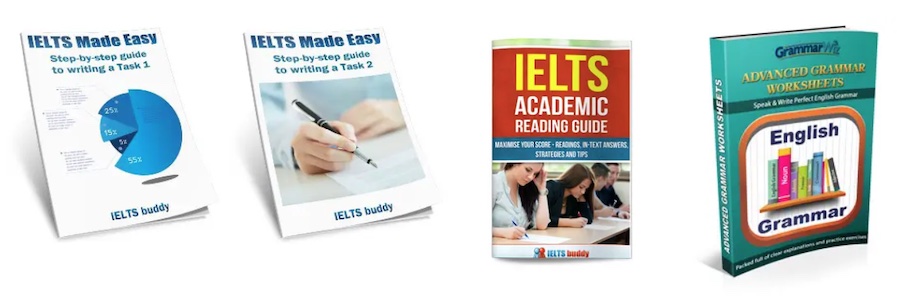

Band 7+ eBooks

"I think these eBooks are FANTASTIC!!! I know that's not academic language, but it's the truth!"

Linda, from Italy, Scored Band 7.5

Bargain eBook Deal! 30% Discount

All 4 Writing eBooks for just $25.86 Find out more >>

IELTS Modules:

Other resources:.

- All Lessons

- Band Score Calculator

- Writing Feedback

- Speaking Feedback

- Teacher Resources

- Free Downloads

- Recent Essay Exam Questions

- Books for IELTS Prep

- Useful Links

Recent Articles

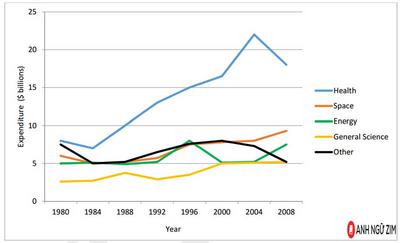

IELTS Line Graph: Governments Expenditure on Research

Jul 23, 24 01:27 PM

House History Essay

Jul 16, 24 04:06 PM

Paraphrasing Activity for IELTS Reading

Jul 13, 24 07:48 AM

Important pages

IELTS Writing IELTS Speaking IELTS Listening IELTS Reading All Lessons Vocabulary Academic Task 1 Academic Task 2 Practice Tests

Connect with us

Before you go...

30% discount - just $25.86 for all 4 writing ebooks.

Copyright © 2022- IELTSbuddy All Rights Reserved

IELTS is a registered trademark of University of Cambridge, the British Council, and IDP Education Australia. This site and its owners are not affiliated, approved or endorsed by the University of Cambridge ESOL, the British Council, and IDP Education Australia.

96 Extinction Essay Topics & Examples

Looking for extinction essay topics? One of the most severe ecological problems is worth exploring.

🏆 A+ Extinction Essay Examples

📌 best extinction essay topics, 🔝 top ideas for an essay about extinction, 👍 endangered species essay topics & title ideas, ❓ research questions about extinction.

Extinction is the termination of a certain living form, usually a species, or a language. The death of the last individual of the species (or the last speaker) is considered to be the moment of extinction. This phenomenon of animal extinction s considered to be the world’s largest threat to wildlife. In the last 50 years, the wildlife population sizes have dropped by 60%. That’s why animal extinction is one of the major ecological issues.

Whether you need to write a research paper or an argumentative essay on extinction, this article will be helpful. It contains top endangered species essay topics, titles, extinction essay examples, etc. Write an A+ essay about extinction with us!

- Preventing Animal Extinction in the UAE In essence, the UAE has been at the forefront of protecting endangered species from extinction and promoting an increment in their population, by putting up breeding programmes which help in multiplication of such animals.

- Wildlife Management and Extinction Prevention in Australia This paper investigates the threats to wildlife in Australia and strategies for managing and preventing their extinction. In summary, this paper examines the threats to wildlife in Australia and outlines strategies for managing and preventing […]

- Dodo Bird and Why It Went Extinct One of the extinct species of bird is the dodo bird. Its extinction has made it hard for scholars to classify the bird when it comes to taxonomy of birds.

- Their Benefits Aside, Human Diets Are Polluting the Environment and Sending Animals to Extinction The fact that the environment and the entire ecosystem have been left unstable in the recent times is in no doubt.

- Animal Extinction: Causes and Effects Due to the increased rates of globalization and the rapid development of industries, the effect that the humankind has been producing on the environment has been amplified.

- Premature Extinction of Species For thousands of years of geological time, the extinction of some species has been balanced by the emergence of the new ones.

- Extinction of minority languages On the other hand, the extinction of minor languages leads to the extinction of certain cultural groups and their individualities, turning the world into a global grey crowd.

- Human Evolution and Animal Extinction The recent scholarly findings prove that invasions of Homo sapiens to the Austronesian and American continents were the major factors that conditioned the extinction of numerous animal species.

- Animal Extinction and What Is Being Done To Help The affected species, the causes of the change, as well as the possible criterion of arresting the situation, forms the subject of their discussion.

- “Extinction Rebellion” News Article by Eells The Extinction Rebellion movement was created in 2018, and, according to the organizers, now it has spread to dozens of countries where there are groups ready to participate in protests.

- Diversity and Extinction of Cyclura Lewisi One of the biggest risks to the population of this species is wild animals. The Grand Cayman blue iguana population is gradually expanding and is predicted to continue to rise as a result of continuing […]

- Extinction of Dinosaurs in North America and Texas It is necessary to identify the reason for the extinction of dinosaurs on the territory of the continent, namely, the state of Texas.

- Seabird Extinction from Invasive Rodent Species This paper will review seabirds’ role in ecosystems, the invasive rodent species and their impact on seabirds, and methods of protecting seabirds from non-native rodents.

- Mathematical Biology: Explaining Population Extinction Species in settings with soft carrying capacities such as those with non-negative value K create a restricted expectation of a variation, given a full past history, is non-positive when the species surpasses the carrying volume.

- The Importance of Saving a Species From Extinction It leads to a lack of surviving members of some species to reproduce in order create a new generation of the extinct species.

- Language Extinction in East Africa Most of the languages in the world fall under the endangered languages category with UNESCO approximating the percentage of endangered languages to be around 60%-80%.

- Extinction of Music Education Plato quoted: “The decisive importance of education in poetry and music: rhythm and harmony sink deep into the recesses of the soul and take the strongest hold there.

- The Cause of Human Extinction: Nature’s Ferocity or People’s Irresponsibility? The following sections will provide statistical data and projections as well as non-scientific scenarios for the end of the world and the extinction of the human race.

- Is Cannibalism the Reason for Neanderthal’s Extinction? They also found that cuts and fractures on the deer bones that were very similar to the ones that were found in the Neanderthal body.

- Chinese Dialects and Extinction Threats The problem of the reduction and extinction of the local dialects is one of the most sensitive and unresolved issues in China.

- Mass Extinction Theories It can thus be speculated that the species that could not withstand the effects of global warming had to become extinct due to the adverse changes in climate.

- Saving Sharks from the Extinction Thus, it is significant for the marshals to guard and secure the naval areas to uncover the abuse and intervene to discontinue the vicious killing of sharks.

- Comparison of Two Archaeological Papers on the Extinction of Animals Due to the Activities of Human Societies. In this study, the varying trends on the abundance of certain species were used to describe changes observed in the hunting practices and the animal species that were hunted.

- Human Activities and their Impact on Species Extinction in Arctic Unfortunately, what should be taken into consideration is the fact that as human interference continues to escalate within the region such as overfishing, oil drilling, population expansion and the effects of global warming this has […]

- Hazard from Space: Mass Extinction Theory The massive impact of extraterrestrial objects did not cause mass extinction of dinosaurs. Dinosaur basis of mass extinction theory do not give plausible explanation for extraterrestrial bodies since they occurred only once during the period […]

- Population Explosion and the Possible Extinction of Humans

- The Continuous Pollution on Earth Post Human Extinction in The World Without Us, a Book by Alan Weisman

- The Endangerment And Mass Extinction of The Tiger: Can We Stop It

- The Wildlife Biodiversity and its Continuous Extinction

- The Permo-Triassic Mass Extinction And The Earth’s Triassic Period

- Mass Extinction of Biodiversity From The Enhanced Greenhouse Effect

- Profit Maximization and the Extinction of Animal Species

- What Are the Consequences of the Removal/Extinction of an Organism from the Food Web

- The Biological Description of the Dodo and Its Extinction

- The Circumstances that Led to the Extinction of Dinosaurs

- We Must Save The Great White Shark From Extinction

- Problem of the Extinction of Many Rare Species

- The Destruction of Natural Habitats and the Extinction of Plants and Animals

- Why Extinction Does Happen It Is Not Indefinite

- Cascades of Failure and Extinction in Evolving Complex Systems

- The Permian Triassic Extinction Event And It’s Effects On Life On Earth

- Upper Estimates of the Mean Extinction Time of a Population with a Constant Carrying Capacity

- What Could Have Caused The Extinction of Dinosaurs

- The Role of Fungus in the Extinction of Dinosaurs

- Saving the Whales: Lessons from the Extinction of the Eastern Arctic Bowhead

- The Extinction, Endangerment, And Captivity of Endangered

- The Effects of Language Extinction on Cultural Identity in Third World Countries

- Sex, Drugs, Disasters, and the Extinction of Dinosaurs by Stephen Jay Gould

- The Ghost of Extinction: Preservation Values and Minimum Viable Population in Wildlife Models

- Recovery After Mass Extinction: Evolutionary Assembly in Large-Scale Biosphere Dynamics

- The Devonian Extinction and the Long Process of Evolution in the Past 300 Million Years

- The Process of De-Extinction And Its Ecological And Moral Consequences

- The Need to Save the Animals from Extinction Using Genetic Engineering

- The Brink Of The Extinction Of America’s Civility And Inclusion

- The Current Extinction Rate Throughout The World: We Must Act Now

- Conservation Biology: Extinction, Habitat Loss, Invasive Species, Overexploitation

- Why Evolution And Extinction Is Essential To Humanity

- The Guam Rail Should Be Saved from Possible Extinction Essay

- The Extinction Event and Life in the Post-Apocalyptic Greenhouse

- Causes of Animal and Plant Extinction, and Its Effects on Humans

- Ultimate Extinction of the Promiscuous Bisexual Galton-Watson Metapopulation

- Saving the Cheetahs of the Serengeti from Extinction

- The Influx of New Languages and Its Dangers to the Extinction of the English Language

- The First Great Whale Extinction: The End of the Bowhead Whale in the Eastern Arctic

- Causes of Canine Extinction and Disappearing Species

- The Themes of Isolation, Extinction and Man’s Limitations in the Poetry of Robert Frost

- The Viability of the Catastrophism Theory in Dinosaur Extinction

- Why The Asian Small-Clawed Otter Is At The Brink Of Extinction

- Species Extinction To Environmental Deterioration

- The Extinction Of Neanderthals And Early Modern Humans

- Did Humans Cause the Mass Extinction of Megafauna During the Late Pleistocene?

- What Are the Consequences of the Extinction of an Organism for the Food Web?

- What Do We Mean by Extinction?

- What Was the Worst Extinction in History?

- What Are the Five Major Extinctions in Earth’s History?

- Are We Overdue for a Mass Extinction?

- What Are the Potential Benefits and Consequences of De-extinction?

- What Could Have Caused the Extinction of Dinosaurs?

- What Events Apparently Triggered the Mass Extinction?

- Why Evolution and Extinction Are Essential to Humanity?

- Why the Asian Small-Clawed Otter Is at the Brink of Extinction?

- Will Global Warming Lead to the Mass Extinction of the Worlds Species?

- What Causes Extinction of Animals?

- What Are the Three Types of Extinction?

- What Is the Cause of Extinction and What Are Its Effects?

- What Causes More Extinction?

- Which Is the Main Cause of the Extinction of Several Species?

- How Are Humans Causing Animal Extinction?

- How Will Extinction Affect Humans?

- What Causes Extinction and What Are Its Impacts?

- Why Is Extinction a Problem?

- How Does Extinction Affect Biodiversity?

- How Does Extinction Affect Evolution?

- What Usually Happens After a Mass Extinction?

- What Is the Advantage of Extinction?

- Cruelty to Animals Titles

- Endangered Species Questions

- Invasive Species Titles

- Animal Rights Research Ideas

- Wildlife Ideas

- Zoo Research Ideas

- Cultural Identity Research Topics

- Animal Ethics Research Ideas

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 28). 96 Extinction Essay Topics & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/extinction-essay-topics/

"96 Extinction Essay Topics & Examples." IvyPanda , 28 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/extinction-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2024) '96 Extinction Essay Topics & Examples'. 28 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "96 Extinction Essay Topics & Examples." February 28, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/extinction-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "96 Extinction Essay Topics & Examples." February 28, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/extinction-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "96 Extinction Essay Topics & Examples." February 28, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/extinction-essay-topics/.

November 1, 2023

20 min read

Can We Save Every Species from Extinction?

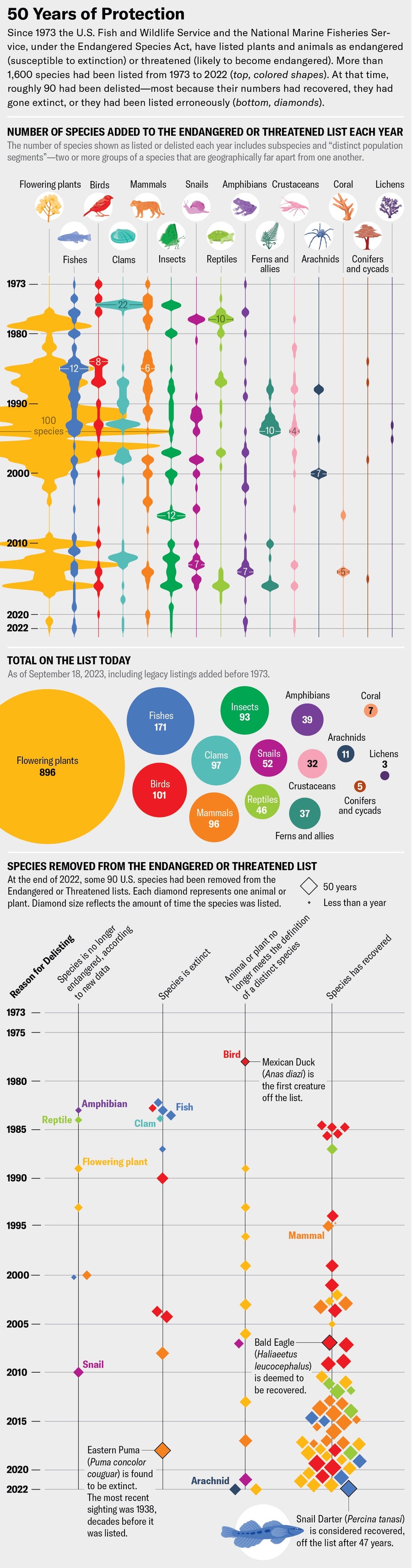

The Endangered Species Act requires that every U.S. plant and animal be saved from extinction, but after 50 years, we have to do much more to prevent a biodiversity crisis

By Robert Kunzig

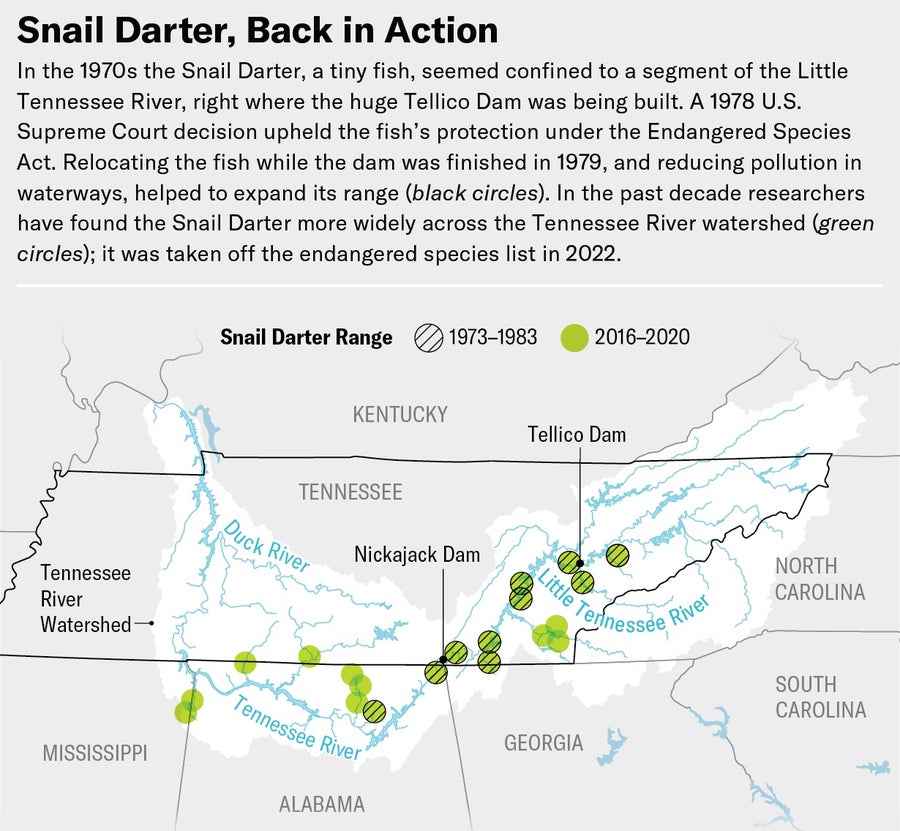

Snail Darter Percina tanasi. Listed as Endangered: 1975. Status: Delisted in 2022.

© Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark

A Bald Eagle disappeared into the trees on the far bank of the Tennessee River just as the two researchers at the bow of our modest motorboat began hauling in the trawl net. Eagles have rebounded so well that it's unusual not to see one here these days, Warren Stiles of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service told me as the net got closer. On an almost cloudless spring morning in the 50th year of the Endangered Species Act, only a third of a mile downstream from the Tennessee Valley Authority's big Nickajack Dam, we were searching for one of the ESA's more notorious beneficiaries: the Snail Darter. A few months earlier Stiles and the FWS had decided that, like the Bald Eagle, the little fish no longer belonged on the ESA's endangered species list. We were hoping to catch the first nonendangered specimen.

Dave Matthews, a TVA biologist, helped Stiles empty the trawl. Bits of wood and rock spilled onto the deck, along with a Common Logperch maybe six inches long. So did an even smaller fish; a hair over two inches, it had alternating vertical bands of dark and light brown, each flecked with the other color, a pattern that would have made it hard to see against the gravelly river bottom. It was a Snail Darter in its second year, Matthews said, not yet full-grown.

Everybody loves a Bald Eagle. There is much less consensus about the Snail Darter. Yet it epitomizes the main controversy still swirling around the ESA, signed into law on December 28, 1973, by President Richard Nixon: Can we save all the obscure species of this world, and should we even try, if they get in the way of human imperatives? The TVA didn't think so in the 1970s, when the plight of the Snail Darter—an early entry on the endangered species list—temporarily stopped the agency from completing a huge dam. When the U.S. attorney general argued the TVA's case before the Supreme Court with the aim of sidestepping the law, he waved a jar that held a dead, preserved Snail Darter in front of the nine judges in black robes, seeking to convey its insignificance.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Now I was looking at a living specimen. It darted around the bottom of a white bucket, bonking its nose against the side and delicately fluttering the translucent fins that swept back toward its tail.

“It's kind of cute,” I said.

Matthews laughed and slapped me on the shoulder. “I like this guy!” he said. “Most people are like, ‘Really? That's it?’ ” He took a picture of the fish and clipped a sliver off its tail fin for DNA analysis but left it otherwise unharmed. Then he had me pour it back into the river. The next trawl, a few miles downstream, brought up seven more specimens.

In the late 1970s the Snail Darter seemed confined to a single stretch of a single tributary of the Tennessee River, the Little Tennessee, and to be doomed by the TVA's ill-considered Tellico Dam, which was being built on the tributary. The first step on its twisting path to recovery came in 1978, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled, surprisingly, that the ESA gave the darter priority even over an almost finished dam. “It was when the government stood up and said, ‘Every species matters, and we meant it when we said we're going to protect every species under the Endangered Species Act,’” says Tierra Curry, a senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity.

Bald Eagle Haliaeetus leucocephalus. Listed as Endangered: 1967. Status: Delisted in 2007. Credit: © Joel Sartore/National Geographic Photo Ark

Today the Snail Darter can be found along 400 miles of the river's main stem and multiple tributaries. ESA enforcement has saved dozens of other species from extinction. Bald Eagles, American Alligators and Peregrine Falcons are just a few of the roughly 60 species that had recovered enough to be “delisted” by late 2023.