About . Click to expand section.

- Our History

- Team & Board

- Transparency and Accountability

What We Do . Click to expand section.

- Cycle of Poverty

- Climate & Environment

- Emergencies & Refugees

- Health & Nutrition

- Livelihoods

- Gender Equality

- Where We Work

Take Action . Click to expand section.

- Attend an Event

- Partner With Us

- Fundraise for Concern

- Work With Us

- Leadership Giving

- Humanitarian Training

- Newsletter Sign-Up

Donate . Click to expand section.

- Give Monthly

- Donate in Honor or Memory

- Leave a Legacy

- DAFs, IRAs, Trusts, & Stocks

- Employee Giving

The top 11 causes of poverty around the world

Feb 3, 2022

Approximately 10% of the world’s population lives in extreme poverty. But why? Updated for 2022, we look at 11 of the top causes of poverty around the world.

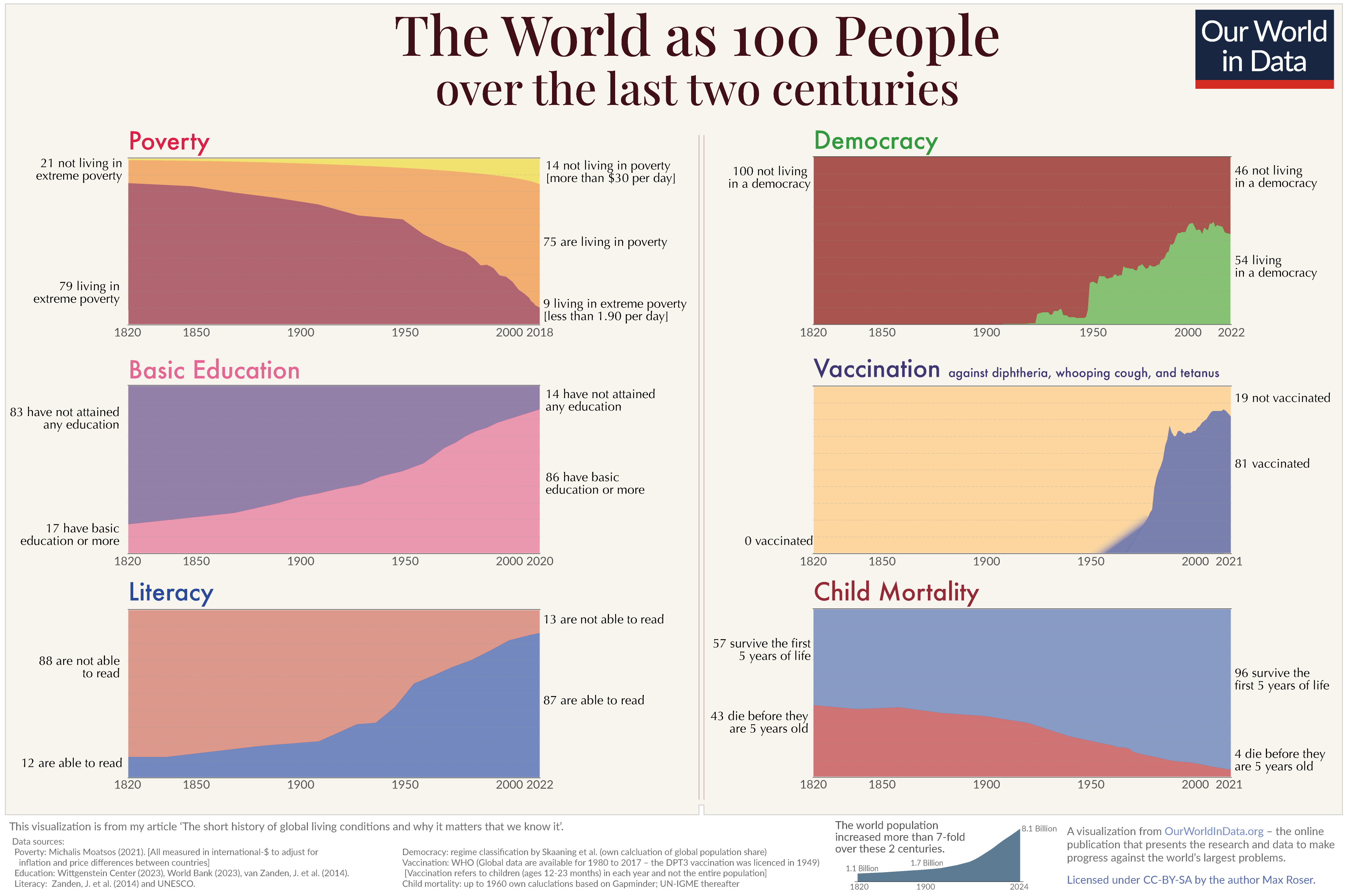

For most of us, living on less than $2 a day seems far removed from reality. But it is the reality for roughly 800 million people around the globe. Approximately 10% of the global population lives in extreme poverty, meaning that they're living below the poverty line of $1.90 per day.

There is some good news: In 1990, that figure was 1.8 billion people. We've made progress. But in the last few years we've also begun to move backwards — in 2019, estimates were closer to 600 million people living in extreme poverty. Climate change and conflict have both hindered progress. The global economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic only made matters worse.

There’s no one single solution to poverty . There isn't a single cause of poverty, either. In fact, most cases of poverty in 2022 are the result of a combination of factors. Understanding what these factors are and how they work together is a critical step to sustainably ending poverty.

Learn more about the causes of poverty — and how we're solving them

1. inequality.

Let's start with something both simple and complex: Inequality is easy enough to understand as a concept. When one group has fewer rights and resources based on an aspect of their identity compared to others in a community, that's inequality. This marginalization could be based on caste, ability, age, health, social status or — most common and most pervasive — gender.

How inequality functions as a cause of poverty, however, is a bit more multifaceted. When people are given fewer rights or assets based on their ethnicity or tribal affiliation, that means they have fewer opportunities to move ahead in life. We see this often in gender inequality , especially when women have fewer rights around their health and economic power. In this case, equality isn't even relative. It doesn't matter that someone has more. What matters is that someone else doesn't have enough.

This is especially harmful when inequality is combined with risk — which is the basic formula we use at Concern to understand the cycle of poverty . A widow raising a family of five won't have the same resources available to her husband. If she lives in an area vulnerable to the effects of climate change, that puts pressure on what few resources she has. In some countries, this is the rule rather than the exception.

To address inequality, we must consider all groups in a community. What's more, to build equality we have to consider equality of results, as opposed to equality of resources.

2. Conflict

If poverty is caused by inequality multiplied by risk, let's talk about risks. At the top of the list of risks for poverty is conflict . Large-scale, protracted crises, such as the decade of civil war in Syria , can grind an otherwise thriving economy to a halt. As fighting continues in Syria, for example, millions have fled their homes (often with nothing but the clothes on their backs). Public infrastructure has been destroyed. Prior to 2011, as few as 10% of Syrians lived below the poverty line. Ten years later, more than 80% of Syrians now live below the poverty line.

But the nature of conflict has changed in the last few decades, and violence has become more localized. This also has a huge impact on communities, especially those that were already struggling. In some ways, it's even harder to cope as these crises go ignored in headlines and primetime news. Fighting can stretch out for years, if not decades, and leave families in a permanent state of alert. This makes it hard to plan for the long-term around family businesses, farms, or education.

3. Hunger, malnutrition, and stunting

You might think that poverty causes hunger (and you would be right!). But hunger is also a cause — and maintainer — of poverty . If a person doesn’t get enough food, they’ll lack the strength and energy needed to work. Or their immune system will weaken from malnutrition and leave them more susceptible to illness that prevents them from getting to work.

In Ethiopia, stunting contributes to GDP losses as high as 16%.

This can lead to a vicious cycle, especially for children. From womb to world, the first 1,000 days of a child’s life are key to ensuring their future health. For children born into low-income families, health is also a key asset to their breaking the cycle of poverty. However, if a mother is malnourished during pregnancy, that can be passed on to her children. The costs of malnutrition may be felt over a lifetime: Adults who were stunted as children earn, on average, 22% less than those who weren't stunted. In Ethiopia, stunting contributes to GDP losses as high as 16%.

4. Poor healthcare systems — especially for mothers and children

As we saw above with the effects of hunger, extreme poverty and poor health go hand-in-hand. In countries with weakened health systems, easily-preventable and treatable illnesses like malaria , diarrhea, and respiratory infections can be fatal. Especially for young children.

When people must travel far distances to clinics or pay for medicine, it drains already vulnerable households of money and assets. This can tip a family from poverty into extreme poverty. For women in particular, pregnancy and childbirth can be a death sentence. Maternal health is often one of the most overlooked areas of healthcare in countries that are still built around patriarchal structures. New mothers and mothers-to-be are often barred from seeking care without their father's or husband's permission. Adolescent girls who are pregnant (especially out of wedlock) face even greater inequities and discrimination.

5. Little (or zero) access to clean water, sanitation, and hygiene

Currently, more than 2 billion people don’t have access to clean water at home. This means that people collectively spend 200 million hours every day walking long distances to fetch water. That’s precious time that could be used working, or getting an education to help secure a job later in life. And if you guessed that most of these 200 million hours are shouldered by women and girls… you're correct. Water is a women's issue as well as a cause of poverty.

Contaminated water can also lead to a host of waterborne diseases, ranging from the chronic to the life-threatening. Poor water infrastructure — such as sanitation and hygiene facilities — can compound this. It can also create other barriers to escaping poverty, such as preventing girls from going to school during their cycles.

6. Climate change

Climate change causes poverty , working as an interdependent link between not only extreme poverty but also many of the other causes on this list — including hunger , conflict, inequality, and a lack of education (see below). One report from the World Bank estimates that the climate crisis has the power to push more than 100 million people into poverty over the next decade.

Many of the world’s poorest populations rely on farming or hunting and gathering to eat and earn a living. Malawi, as an example, is 80% agrarian. They often have only just enough food and assets to last through the next season, and not enough reserves to fall back on in the event of a poor harvest. So when climate change or natural disasters (including the widespread droughts caused by El Niño ) leave millions of people without food, it pushes them further into poverty, and can make recovery even more difficult.

How climate change keeps people in poverty

By 2030, climate change could force more than 100 million people into extreme poverty.

7. Lack of education

Not every person without an education is living in extreme poverty. But most adults living in extreme poverty did not receive a quality education. And, if they have children, they're likely passing that on to them. There are many barriers to education around the world , including a lack of money for uniforms and books or a cultural bias against girls’ education .

But education is often referred to as the great equalizer. That's because it can open the door to jobs and other resources and skills that a family needs to not just survive, but thrive. UNESCO estimates that 171 million people could be lifted out of extreme poverty if they left school with basic reading skills. Poverty threatens education, but education can also help end poverty .

8. Poor public works and infrastructure

What if you have to go to work, but there are no roads to get you there? Or what if heavy rains have flooded your route and made it impossible to travel? We're used to similar roadblocks (so to speak) in the United States. But usually we can rely on our local governments to step in.

A lack of infrastructure — from roads, bridges, and wells, to cables for light, cell phones, and internet — can isolate communities living in rural areas. Living off the grid often means living without the ability to go to school, work, or the market to buy and sell goods. Traveling further distances to access basic services not only takes time, it costs money, keeping families in poverty.

As we've found in the last two years, isolation limits opportunity. Without opportunity, many find it difficult, if not impossible, to escape extreme poverty.

9. Global health crises including epidemics and pandemics

Speaking of things we've learned over the last two years… A poor healthcare system that affects individuals, or even whole communities, is one cause of poverty. But a large-scale epidemic or pandemic merits its own spot on this list. COVID-19 isn't the first time a public health crisis has fueled the cycle of poverty. More localized epidemics like Ebola in West Africa (and, later, in the DRC ), cholera in Haiti or the DRC, or malaria in Sierra Leone have demonstrated how local and national governments can grind to a halt while working to stop the spread of a disease, provide resources to frontline workers and centers, and come up with contingency plans as day-to-day life is disrupted.

All of this comes, naturally, at a cost. In Guinea, Liberia , and Sierra Leone — the three countries hit hardest by the 2014-16 West African Ebola epidemic — an estimated $2.2 billion was lost across all three countries' GDPs in 2015 as a direct result of the epidemic. This included losses in the private sector, agricultural production, and international trade.

The crisis in Kenya: Climate, COVID, and hunger

The worst drought in four decades, the worst locust invasion in seven, plus the domino effects of a global pandemic have northern Kenyans living out an underreported crisis and facing an uncertain future.

10. Lack of social support systems

In the United States, we're familiar with social welfare programs that people can access if they need healthcare or food assistance. We also pay into insurances against unemployment and fund social security through our paychecks. Theses systems ensure that we have a safety net to fall back on if we lose our job or retire.

But not every government can provide this type of help to its citizens. Without that safety net, there’s nothing to stop vulnerable families from backsliding further into extreme poverty. Especially in the face of the unexpected.

11. Lack of personal safety nets

If a family or community has reserves in place, they can weather some risk. They can fall back on savings accounts or even a low-interest loan in the case of a health scare or an unexpected layoff, even if the government doesn't have support systems to cover them. Proper food storage systems can help stretch a previous harvest if a drought or natural disaster ruins the next one.

At its core, poverty is a lack of basic assets or a lack on return from what assets a person has.

People living in extreme poverty can't rely on these safety nets, however. At its core, poverty is a lack of basic assets or a lack on return from what assets a person has. This leads to negative coping mechanisms, including pulling children out of school to work (or even marry ), and selling off assets to buy food. That can help a family make it through one bad season, but not another. For communities constantly facing climate extremes or prolonged conflict, the repeated shocks can send a family reeling into extreme poverty and prevent them from ever recovering.

Solutions to Poverty to Get Us To 2030

What would Zero Poverty look like for the world in 2030? Here are a few starting points.

How can you help?

At Concern, we believe that zero poverty is possible, especially when we work with communities to address both inequalities and risks. Last year, we reached 36.9 million people with programs designed to address the specific causes of extreme poverty in countries, communities, and families.

Pictured in the banner image for this story is one of those people, Adrenise Lusa. Born 60 years ago in the DRC's Manono Territory, Adrenise joined Concern's Graduation program in 2019 and participated in trainings on income generation and entrepreneurship, which gave her ideas on how to increase her production and income. With monthly cash transfers as part of Graduation and a loan from her community Village Savings and Loans Association, she invested in a few income-generating activities including goat rearing and trading oil, maize, and cassava. Prior to joining Graduation, she had the ideas. But, as she explains, "I didn’t start these businesses because I just didn’t have enough money."

Since launching her new ventures, Adrenise has increased her income from approximately 30,000 francs per month to anywhere between 100–400,000 francs per month, depending on the season. She's used her additional income to buy a plot of land and build a new house, feed her family with more nutritious food, and send her son and daughter to university.

You can make your own impact by supporting our efforts working with the world’s poorest communities. Learn more about the other ways you can help the fight against poverty.

More about the causes of poverty

Extreme Poverty and Hunger: A Vicious Cycle

Sign up for our newsletter.

Get emails with stories from around the world.

You can change your preferences at any time. By subscribing, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

Miracle Foundation

Transform the lives of orphan children and change their story.

Stories: THE MIRACLE BLOG

The miracle blog, understanding the root causes of global poverty.

Marissa Ratton

On the marketing team at Miracle Foundation, and frequent blog contributor.

Publication Date: February 8, 2024

Overcoming poverty is a complex issue. By understanding and tackling the underlying reasons behind poverty, we can take strides toward creating a world where poverty is replaced with hope and opportunity.

Four Global Causes of Poverty:

- Structural Inequality: The first step is to recognize the impact of structural inequalities within societies. These inequalities create disparities in access to resources, opportunities, and decision-making power, and addressing them is essential for breaking the cycle of poverty.

- Limited Access to Education: Educational opportunities serve as a gateway out of poverty, yet millions encounter barriers such as inadequate infrastructure, gender-based discrimination, and economic constraints. Bridging the global education gap is vital for empowering communities and eliminating global poverty. We must ensure that every child goes to school and thrives in the educational environment. And actively commit to breaking down barriers and creating a pathway for a brighter future.

- Economic Injustice: Unfair economic systems contribute significantly to global poverty. Exploitative labor practices, unequal distribution of wealth, and limited access to credit and resources hinder the economic progress of vulnerable populations. Addressing these economic injustices is critical to a sustainable poverty solution.

- Social Discrimination and Exclusion: Marginalized social groups often bear the brunt of poverty’s weight disproportionately. In our pursuit of a world where everyone has an equal opportunity to thrive, combating social discrimination and fostering inclusivity becomes imperative. At the core of our mission lies the commitment to helping families thrive; we recognize that they are the heartbeat of flourishing communities.

The elimination of global poverty demands comprehensive and collaborative solutions. At Miracle Foundation, we approach our work strategically, guided by data-driven decisions, utilizing our Thrive Scale™ methodology . We strive to create a pathway for a brighter, more equitable future by connecting people with necessary resources and support. We are unwavering in our mission to contribute to the global effort of eradicating poverty and fostering thriving, empowered communities worldwide.

Want to stay connected? Sign up for our newsletter here.

- Our Beliefs

- Our Partners

- Miracle Foundation India

- See our Financials

- Our Global Work

- Our Local Work

- Sustainable Development Goals

- UN Rights of the Child

- Give a Gift

- Get Involved

- Join Miracle Village

- Host a Fundraiser

- Become a Corporate Partner

- Work with Us

- Be an Intern

- Watch our Videos

- Listen to Podcasts

- See our Press

- Read our Stories

- Life Skills Education

- Positive Parenting

- Psychosocial Support

- Case Management Toolkit

- Full ThriveWell Page

Sign up for our occasional newsletter below:

Subscribe to receive updates.

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.

You have Successfully Subscribed!

Livelihoods

Health and nutrition

Emergencies

Gender equality

Climate and environment

View all countries

Secondary Schools

Primary Schools

Post Primary Debates

Primary Debates

Educational Resources

Fundraising in Schools

1Planet4All

View all news

Listen to our podcast

Our history

Testimonials

Institutional donors

Public donations

Annual reports

How money is spent

How we are governed

Codes and policies

Supply chains

- South Sudan Hunger Appeal

- Gaza Crisis Appeal

Sudan Crisis Appeal

Concern Summer Raffle

Start your own fundraiser

Find a friend to sponsor

Fundraise locally

Sign up for Irish Life Dublin Marathon

Donate in memory

Leave a gift in your Will

- Concern Gifts

Your donation and tax back

Become a corporate supporter

Partner with us

Concern Humanitarian Fund

Women of Concern Annual Awards

Staff fundraising

Payroll giving

Knowledge Matters Magazine

Global Hunger Index

Evaluations

Learning Papers

Donate today

Where we work

Schools and youth

Global Activism

Latest news

Read our 2023 annual report

How we raise money

Transparency and accountability

Fundraise for Concern

Subscribe to Green Shoots

Other ways to give

Philanthropy & Major Gifts

Corporate support

Volunteer in Ireland

Knowledge Hub

Knowledge Hub resources

- End The Wait Appeal

- Green Shoots

- Global Hunger Index 2023

- Volunteer with us

- Job vacancies

The top 11 causes of poverty around the world

Approximately 10% of the world’s population lives in extreme poverty. But why? Updated for 2022, we look at 11 of the top causes of poverty around the world.

For most of us, living on less than $2 a day seems far removed from reality. But it is the reality for roughly 800 million people around the globe. Approximately 10% of the global population lives in extreme poverty, meaning that they're living below the poverty line of $1.90 per day.

There is some good news: In 1990, that figure was 1.8 billion people. We've made progress. But in the last few years we've also begun to move backwards — in 2019, estimates were closer to 600 million people living in extreme poverty. Climate change and conflict have both hindered progress. The global economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic only made matters worse.

There’s no one catchall solution to poverty, nor is there a single cause of poverty. In fact, most cases of poverty in 2022 are the result of a combination of factors. Understanding what these factors are and how they work together is a critical step to sustainably ending poverty.

1. Inequality

Let's start with something both simple and complex: Inequality is easy enough to understand as a concept. When one group has fewer rights and resources based on an aspect of their identity compared to others in a community, that's inequality. This marginalisation could be based on caste, ability, age, health, social status or — most common and most pervasive — gender.

How inequality functions as a cause of poverty, however, is a bit more multifaceted. When people are given fewer rights or assets based on their ethnicity or tribal affiliation, that means they have fewer opportunities to move ahead in life. We see this often in gender inequality, especially when women have fewer rights around their health and economic power. In this case, equality isn't even relative. It doesn't matter that someone has more. What matters is that someone else doesn't have enough.

This is especially harmful when inequality is combined with risk — which is the basic formula we use at Concern to understand the cycle of poverty. A widow raising a family of five won't have the same resources available to her husband. If she lives in an area vulnerable to the effects of climate change, that puts pressure on what few resources she has. In some countries, this is the rule rather than the exception.

To address inequality, we must consider all groups in a community. What's more, to build equality we have to consider equality of results, as opposed to equality of resources.

2. Conflict

If poverty is caused by inequality multiplied by risk, let's talk about risks. At the top of the list of risks for poverty is conflict. Large-scale, protracted crises, such as the 11 years of civil war in Syria, can grind an otherwise thriving economy to a halt. As fighting continues in Syria, for example, millions have fled their homes, often with nothing but the clothes on their backs. Public infrastructure has been destroyed. Prior to 2011, as few as 10% of Syrians lived below the poverty line. Now, more than 80% of Syrians now live below the poverty line.

But the nature of conflict has changed in the last few decades, and violence has become more localised. This has a huge impact on communities, especially those that were already struggling. In some ways, it's even harder to cope as these crises go ignored in headlines and primetime news. Fighting can stretch out for years, if not decades, and leave families in a permanent state of alert. This makes it hard to plan for the long-term around family businesses, farms, or education.

3. Hunger, malnutrition, and stunting

You might think that poverty causes hunger, and you would be right!. But hunger is also a cause — and maintainer — of poverty. If a person doesn’t get enough food, they’ll lack the strength and energy needed to work. Or their immune system will weaken from malnutrition and leave them more susceptible to illness that prevents them from getting to work.

This can lead to a vicious cycle, especially for children. From womb to world, the first 1,000 days of a child’s life are key to ensuring their future health. For children born into low-income families, health is also a key asset to their breaking the cycle of poverty. However, if a mother is malnourished during pregnancy, that can be passed on to her children. The costs of malnutrition may be felt over a lifetime: Adults who were stunted as children earn, on average, 22% less than those who weren't stunted. In Ethiopia, stunting contributes to GDP losses as high as 16%.

4. Poor healthcare systems — especially for mothers and children

As we saw above with the effects of hunger, extreme poverty and poor health go hand-in-hand. In countries with weakened health systems, easily preventable and treatable illnesses like malaria, diarrhoea, and respiratory infections can be fatal. Especially for young children.

When people must travel far distances to clinics or pay for medicine, it drains already vulnerable households of money and assets. This can tip a family from poverty into extreme poverty. For women in particular, pregnancy and childbirth can be a death sentence. Maternal health is often one of the most overlooked areas of healthcare in countries that are still built around patriarchal structures. New mothers and mothers-to-be are often barred from seeking care without their father's or husband's permission. Adolescent girls who are pregnant (especially out of wedlock) face even greater inequities and discrimination.

5. Little (or zero) access to clean water, sanitation, and hygiene

Currently, more than 2 billion people don’t have access to clean water at home. This means that people collectively spend 200 million hours every day walking long distances to fetch water. That’s precious time that could be used working, or getting an education to help secure a job later in life. And if you guessed that most of these 200 million hours are shouldered by women and girls… you're correct. Water is a women's issue as well as a cause of poverty.

Contaminated water can also lead to a host of waterborne diseases, ranging from the chronic to the life-threatening. Poor water infrastructure — such as sanitation and hygiene facilities — can compound this. It can also create other barriers to escaping poverty, such as preventing girls from going to school during their menstrual cycles.

6. Climate change

Climate change causes poverty, working as an interdependent link between not only extreme poverty but also many of the other causes on this list — including hunger, conflict, inequality, and a lack of education (see below). One report from the World Bank estimates that the climate crisis has the power to push more than 100 million people into poverty over the next decade.

Many of the world’s poorest populations rely on farming or hunting and gathering to eat and earn a living. Malawi, as an example, is 80% agrarian. They often have only just enough food and assets to last through the next season, and not enough reserves to fall back on in the event of a poor harvest. So when climate change or natural disasters (including the widespread droughts caused by El Niño) leave millions of people without food, it pushes them further into poverty, and can make recovery even more difficult.

7. Lack of education

Not every person without an education is living in extreme poverty. But most adults living in extreme poverty did not receive a quality education. And, if they have children, they're likely passing that on to them. There are many barriers to education around the world, including a lack of money for uniforms and books or a cultural bias against girls’ education.

But education is often referred to as the great equaliser. That's because it can open the door to jobs and other resources and skills that a family needs to not just survive, but thrive. UNESCO estimates that 171 million people could be lifted out of extreme poverty if they left school with basic reading skills. Poverty threatens education, but education can also help end poverty.

8. Poor public works and infrastructure

What if you have to go to work, but there are no roads to get you there? Or what if heavy rains have flooded your route and made it impossible to travel? We're used to similar roadblocks (so to speak) in Ireland. But usually we can rely on our local governments to step in.

A lack of infrastructure — from roads, bridges, and wells, to cables for light, cellphones and internet — can isolate communities living in rural areas. Living off the grid often means living without the ability to go to school, work, or the market to buy and sell goods. Traveling further distances to access basic services not only takes time, it costs money, keeping families in poverty.

As we've found in the last two years, isolation limits opportunity. Without opportunity, many find it difficult, if not impossible, to escape extreme poverty.

9. Global health crises including epidemics and pandemics

Speaking of things we've learned over the last two years… A poor healthcare system that affects individuals, or even whole communities, is one cause of poverty. But a large-scale epidemic or pandemic merits its own spot on this list. COVID-19 isn't the first time a public health crisis has fueled the cycle of poverty. More localised epidemics like Ebola in West Africa (and, later, in the DRC), cholera in Haiti or the DRC, or malaria in Sierra Leone have demonstrated how local and national governments can grind to a halt while working to stop the spread of a disease, provide resources to frontline workers and centers, and come up with contingency plans as day-to-day life is disrupted.

All of this, naturally, comes at a cost. In Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone — the three countries hit hardest by the 2014-16 West African Ebola epidemic — an estimated $2.2 billion was lost across all three countries' GDPs in 2015 as a direct result of the epidemic. This included losses in the private sector, agricultural production, and international trade.

10. Lack of social support systems

In Ireland, we're familiar with social welfare programmes that people can access if they need healthcare or food assistance. We also pay into insurances against unemployment and fund social security through our paychecks. These systems ensure that we have a safety net to fall back on if we lose our job or when we retire.

But not every government can provide this type of help to its citizens. Without that safety net, there’s nothing to stop vulnerable families from backsliding further into extreme poverty. Especially in the face of the unexpected.

11. Lack of personal safety nets

If a family or community has reserves in place, they can weather some risk. They can fall back on savings accounts or even a low-interest loan in the case of a health scare or an unexpected layoff, even if the government doesn't have support systems to cover them. Proper food storage systems can help stretch a previous harvest if a drought or natural disaster ruins the next one.

At its core, poverty is a lack of basic assets or a lack on return from what assets a person has.

People living in extreme poverty can't rely on these safety nets, however. At its core, poverty is a lack of basic assets or a lack on return from what assets a person has. This leads to negative coping mechanisms, including pulling children out of school to work (or even marry), and selling off assets to buy food. That can help a family make it through one bad season, but not another. For communities constantly facing climate extremes or prolonged conflict, the repeated shocks can send a family reeling into extreme poverty and prevent them from ever recovering.

How can you help?

At Concern, we believe that zero poverty is possible, especially when we work with communities to address both inequalities and risks. Last year, we reached 36.9 million people with programmes designed to address the specific causes of extreme poverty in countries, communities, and families.

Pictured in the banner image for this story is one of those people, Adrenise Lusa. Born 60 years ago in the DRC's Manono Territory, Adrenise joined Concern's Graduation programme in 2019 and participated in trainings on income generation and entrepreneurship, which gave her ideas on how to increase her production and income. With monthly cash transfers as part of Graduation and a loan from her community Village Savings and Loans Association, she invested in a few income-generating activities including goat rearing and trading oil, maize, and cassava.

Prior to joining Graduation, she had the ideas. But, as she explains, "I didn’t start these businesses because I just didn’t have enough money". Since launching her new ventures, Adrenise has increased her income from approximately 30,000 francs per month to anywhere between 100–400,000 francs per month, depending on the season. She's used her additional income to buy a plot of land and build a new house, feed her family with more nutritious food, and send her son and daughter to university. You can make your own impact by supporting our efforts working with the world’s poorest communities. Learn more about the other ways you can help the fight against poverty.

Share your concern

Content Search

11 top causes of global poverty.

Around 8% of the world’s population lives in extreme poverty — but do you know why? We look at 11 of the top causes of global poverty.

Living on less than $2 a day feels like an impossible scenario, but’s a reality for around 600 million people in our world today. Approximately 8% of the global population lives in extreme poverty, commonly defined as surviving on only $1.90 a day, or less

There is some good news: In 1990, that figure was 1.8 billion people, so serious progress has been made. While many wonder if we can really end extreme poverty , we at Concern believe the end is not only possible — but possible within our lifetimes. There’s no “magic bullet” solution to poverty , but understanding its causes is a good first step. Here are 11 of those causes, fully revised for 2020.

1. INEQUALITY AND MARGINALIZATION

“Inequality” is an easy, but sometimes misleading term used to describe the systemic barriers leaving groups of people without a voice or representation within their communities. For a population to escape poverty, all groups must be involved in the decision-making process — especially when it comes to having a say in the things that determine your place in society. Some of these may be obvious, but in other situations, it can be subtle.

Gender inequality, caste systems, marginalization based on race or tribal affiliations are all economic and social inequalities that mean the same thing: Little to no access to the resources needed to live a full, productive life. When combined with different combinations of vulnerability and hazards which comprise the rest of this list — a marginalized community may become even more vulnerable to the cycle of poverty .

2. CONFLICT

Conflict is one of the most common forms of risk driving poverty today. Large-scale, protracted violence that we’ve seen in areas like Syria can grind society to a halt, destroying infrastructure and causing people to flee (often with nothing but the clothes on their backs). In its tenth year of conflict, Syria’s middle class has been all but destroyed, and over 80% of the population now lives below the poverty line.

But even small bouts of violence can have huge impacts on communities that are already struggling. For example, if farmers are worried about their crops being stolen, they won’t invest in planting. Women also bear the brunt of conflict , which adds a layer of inequality to all conflict: During periods of violence, female-headed households become very common. And because women often have difficulty getting well-paying work and are typically excluded from community decision-making, their families are particularly vulnerable.

3. HUNGER, MALNUTRITION, AND STUNTING

You might think that poverty causes hunger (and you would be right!), but hunger is also a cause — and maintainer — of poverty. If a person doesn’t get enough food, they’ll lack the strength and energy needed to work (or their immune system will weaken from malnutrition and leave them more susceptible to illness that prevents them from getting to work).

The first 1,000 days of a child’s life (from womb to world) are key to ensuring their future health and likelihood of staying out of poverty. If a mother is malnourished during pregnancy, that can be passed on to her children, leading to wasting (low weight for height) or stunting (low height for age). Child stunting , both physical and cognitive, can lead to a lifetime of impacts: Adults who were stunted as children earn, on average, 22% less than those who weren’t stunted. In Ethiopia, stunting contributes to GDP losses as high as 16%.

ADULTS WHO WERE STUNTED AS CHILDREN EARN, ON AVERAGE, 22% LESS THAN THOSE WHO WEREN’T STUNTED. IN ETHIOPIA, STUNTING CONTRIBUTES TO GDP LOSSES AS HIGH AS 16%.

4. POOR HEALTHCARE SYSTEMS — ESPECIALLY FOR MOTHERS AND CHILDREN

Extreme poverty and poor health often go hand in hand. In countries where health systems are weak, easily preventable and treatable illnesses like malaria, diarrhea, and respiratory infections can be fatal — especially for young children. And when people must travel far distances to clinics or pay for medicine, it drains already vulnerable households of money and assets, and can tip a family from poverty into extreme poverty.

For some women, pregnancy and childbirth can be a death sentence. In many of the countries where Concern works, access to quality maternal healthcare is poor. Pregnant and lactating mothers face a multitude of barriers when seeking care, from not being allowed to go to a clinic without a male chaperone to receiving poor or even abusive care from a doctor. This is especially true for adolescent girls aged 18 and under, leaving mothers-to-be and their children at increased risk for disease and death.

5. LITTLE OR NO ACCESS TO CLEAN WATER, SANITATION, AND HYGIENE

Currently, more than 2 billion people don’t have access to clean water at home. This means that people (which is to say, women and girls) collectively spend some 200 million hours every day walking long distances to fetch water. That’s precious time that could be used working, or getting an education to help secure a job later in life.

Contaminated water can also lead to a host of waterborne diseases, ranging from the chronic to the life-threatening. Poor water infrastructure — such as sanitation and hygiene facilities — can compound this, or create other barriers to escaping poverty, such as keeping girls out of school during menstruation.

6. CLIMATE CHANGE

Climate change creates hunger , whether through too little water (drought) or too much ( flooding ), and its effects contribute to the cycle of poverty in several other ways including disproportionately affecting women, creating refugees, and even influencing conflict. One World Bank estimates that climate change has the power to push more than 100 million people into poverty over the next decade.

Many of the world’s poorest populations rely on farming or hunting and gathering to eat and earn a living — for example, Malawi is 80% agrarian. They often have only just enough food and assets to last through the next season, and not enough reserves to fall back on in the event of a poor harvest. So when climate change or natural disasters (including the widespread droughts caused by El Niño ) leave millions of people without food, it pushes them further into poverty, and can make recovery even more difficult.

7. LACK OF EDUCATION

Not every person without an education is living in extreme poverty. But most of the extremely poor don’t have an education. There are many barriers to education around the world , including a lack of money for uniforms and books, a bias against girls’ education , or many of the other causes of poverty mentioned here.

But education is often referred to as the great equalizer, because it can open the door to jobs and other resources and skills that a family needs to not just survive, but thrive. UNESCO estimates that 171 million people could be lifted out of extreme poverty if they left school with basic reading skills. Poverty threatens education, but education can also help end poverty .

8. POOR PUBLIC WORKS AND INFRASTRUCTURE

Imagine that you have to go to work, but there are no roads to get you there. Or heavy rains have flooded your route and made it impossible to travel. A lack of infrastructure — from roads, bridges, and wells, to cables for light, cell phones, and internet — can isolate communities living in rural areas. Living off the grid often means living without the ability to go to school, work, or the market to buy and sell goods. Traveling further distances to access basic services not only takes time, it costs money, keeping families in poverty.

Isolation limits opportunity. Without opportunity, many find it difficult, if not impossible, to escape extreme poverty.

ISOLATION LIMITS OPPORTUNITY.

9. LACK OF GOVERNMENT SUPPORT

Many people living in the United States are familiar with social welfare programs that people can access if they need healthcare or food assistance. But not every government can provide this type of help to its citizens — and without that safety net, there’s nothing to stop vulnerable families from backsliding further into extreme poverty. Ineffective governments also contribute to several of the other causes of extreme poverty mentioned above, as they are unable to provide necessary infrastructure or healthcare, or ensure the safety and security of their citizens in the event of conflict.

10. LACK OF JOBS OR LIVELIHOODS

This might seem like a no-brainer: Without a job or a livelihood, people will face poverty. Dwindling access to productive land (often due to conflict, overpopulation, or climate change) and overexploitation of resources like fish or minerals puts increasing pressure on many traditional livelihoods. In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) for example, most of the population lives in rural communities where natural resources have been plundered over centuries of colonial rule — while conflict over land has forced people away from their source of income and food. Now, more than half of the country lives in extreme poverty.

11. LACK OF RESERVES

All of the above risk factors — from conflict to climate change or even a family illness — can be weathered if a family or community has reserves in place. Cash savings and loans can offset unemployment due to conflict or illness. Proper food storage systems can help if a drought or natural disaster ruins a harvest.

People living in extreme poverty usually don’t have these means available. This means that, when a risk turns into a disaster, they turn to negative coping mechanisms, including pulling children out of school to work (or even marry ), and selling off assets to buy food. That can help a family make it through one bad season, but not another. For communities constantly facing climate extremes or prolonged conflict, the repeated shocks can send a family reeling into extreme poverty and prevent them from ever recovering.

Related Content

World + 38 more

Islamic Relief Worldwide: Global Reach, Impact and Learning Report - Reporting Period January - December 2023 (June 2024)

World + 45 more

Islamic Relief Worldwide 2023: Annual Report & Financial Statements

Norway’s humanitarian strategy 2024–2029, the sustainable development goals report 2024 [en/ar/ru/zh].

The evolution of global poverty, 1990-2030

Download the full working paper

Subscribe to the Sustainable Development Bulletin

Homi kharas and homi kharas senior fellow - global economy and development , center for sustainable development meagan dooley meagan dooley former senior research analyst - global economy and development , center for sustainable development.

February 2, 2022

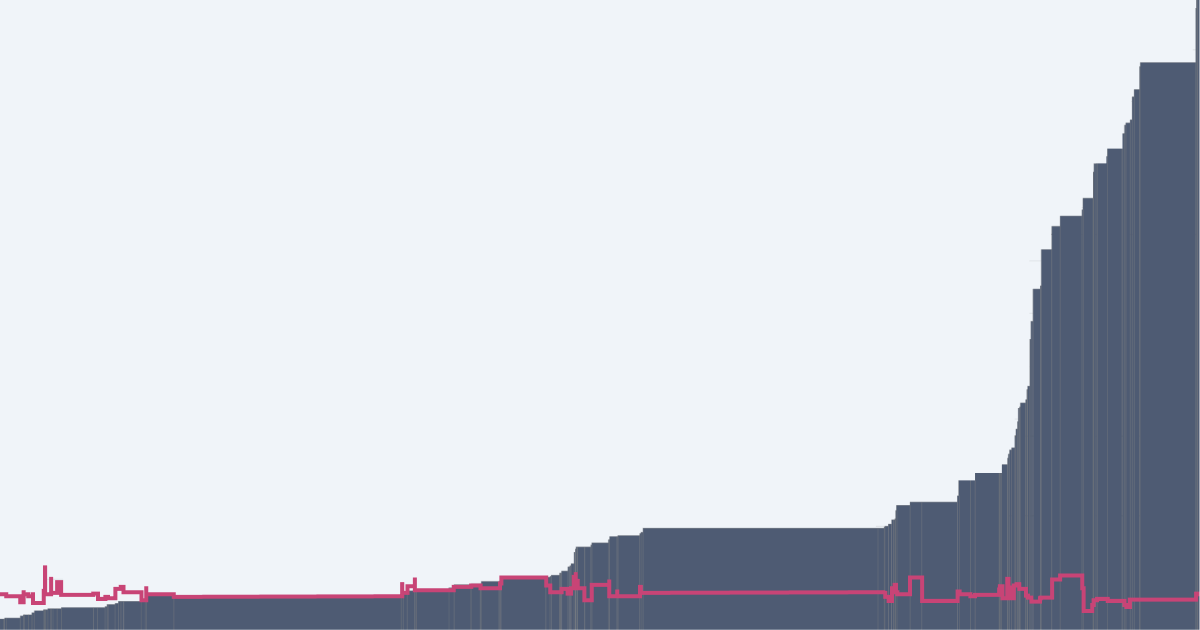

The last 30 years have seen dramatic reductions in global poverty, spurred by strong catch-up growth in developing countries, especially in Asia. By 2015, some 729 million people, 10% of the population, lived under the $1.90 a day poverty line, greatly exceeding the Millennium Development Goal target of halving poverty. From 2012 to 2013, at the peak of global poverty reduction, the global poverty headcount fell by 130 million poor people.

This success story was dominated by China and India. In December 2020, China declared it had eliminated extreme poverty completely . India represents a more recent success story. Strong economic growth drove poverty rates down to 77 million, or 6% of the population, in 2019. India will, however, experience a short-term spike in poverty due to COVID-19, before resuming a strong downward path. By 2030, India is likely to essentially eliminate extreme poverty, with less than 5 million people living below the $1.90 line. By 2030, the only Asian countries that are unlikely to meet the goal of ending extreme poverty are Afghanistan, Papua New Guinea, and North Korea.

In other parts of the world, poverty trends are disappointing. In Latin America, poverty fell rapidly at the beginning of this century but has been rising since 2015, with no substantial reductions forecast by the end of this decade. In Africa, poverty has been rising steadily, thanks to rapid population growth and stagnant economic growth. Exacerbated by a pandemic-induced rise in poverty of 11%, African poverty shows little signs of decline through 2030.

Related Content

Homi Kharas, Kristofer Hamel, Martin Hofer

December 13, 2018

Homi Kharas, Kristofer Hamel, Martin Hofer, Baldwin Tong

May 23, 2019

Jasmin Baier, Kristofer Hamel

October 17, 2018

These trends point to the emergence of a very different poverty landscape. Whereas in 1990, poverty was concentrated in low-income, Asian countries, today’s (and tomorrow’s) poverty is largely found in sub-Saharan Africa and fragile and conflict-affected states. By 2030, sub-Saharan African countries will account for 9 of the top 10 countries by poverty headcount. Sixty percent of the global poor will live in fragile and conflict-affected states. Many of the top poverty destinations in the next decade will fall into both of these categories: Nigeria, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mozambique and Somalia. Global efforts to achieve the SDGs by 2030, including eliminating extreme poverty, will be complicated by the concentration of poverty in these fragile and hard-to-reach contexts.

By 2030, poverty will be associated not just with countries, but with specific places within countries. Middle-income countries will be home to almost half of the global poor, a dramatic shift from just 40 years earlier. Nigeria is now the global face of poverty, overtaking India as the top poverty destination in 2019. (While India temporarily regained its title due to COVID-19, which pushed many vulnerable Indians back below the poverty line, Nigeria will reclaim the top spot by 2022.) In 2015, Nigeria was home to 80 million poor people, or 11% of global poverty; by 2030, this number could grow to 18%, or 107 million.

Poverty numbers and trends have traditionally been reported on a country-by-country basis. However, today we see that low-income countries have significant corridors of prosperity, while middle-income countries can have large pockets of poverty. With advances in geospatial and sub-national data , there is a growing push to move from country-wide metrics to sub-national data, in order to better identify and target these poverty “hotspots.”

Global Economy and Development

Center for Sustainable Development

Emily Gustafsson-Wright, Elyse Painter

August 9, 2024

Ebenezer Obadare

August 8, 2024

Vera Esperança Dos Santos Daves De Sousa

August 7, 2024

The World Bank Group is committed to fighting poverty in all its dimensions. We use the latest data, evidence and analysis to help countries develop policies to improve people's lives, with a focus on the poorest and most vulnerable.

Around 700 million people live on less than $2.15 per day, the extreme poverty line. Extreme poverty remains concentrated in parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, fragile and conflict-affected areas, and rural areas.

After decades of progress, the pace of global poverty reduction began to slow by 2015, in tandem with subdued economic growth. The Sustainable Development Goal of ending extreme poverty by 2030 remains out of reach.

Global poverty reduction was dealt a severe blow by the COVID-19 pandemic and a series of major shocks during 2020-22, causing three years of lost progress. Low-income countries were most impacted and have yet to recover. In 2022, a total of 712 million people globally were living in extreme poverty, an increase of 23 million people compared to 2019.

We cannot reduce poverty and inequality without also addressing intertwined global challenges, including slow economic growth, fragility and conflict, and climate change.

Climate change is hindering poverty reduction and is a major threat going forward. The lives and livelihoods of poor people are the most vulnerable to climate-related risks.

Millions of households are pushed into, or trapped in, poverty by natural disasters every year. Higher temperatures are already reducing productivity in Africa and Latin America, and will further depress economic growth, especially in the world’s poorest regions.

Eradicating poverty requires tackling its many dimensions. Countries cannot adequately address poverty without also improving people’s well-being in a comprehensive way, including through more equitable access to health, education, and basic infrastructure and services, including digital.

Policymakers must intensify efforts to grow their economies in a way that creates high quality jobs and employment, while protecting the most vulnerable.

Jobs and employment are the surest way to reduce poverty and inequality. Impact is further multiplied in communities and across generations by empowering women and girls, and young people.

Last Updated: Apr 02, 2024

Closing the gaps between policy aspiration and attainment

Too often, there is a wide gap between policies as articulated and their attainment in practice—between what citizens rightfully expect, and what they experience daily. Policy aspirations can be laudable, but there is likely to be considerable variation in the extent to which they can be realized, and in which groups benefit from them. For example, at the local level, those who have the least influence in a community might not be able to access basic services. It is critical to forge implementation strategies that can rapidly and flexibly respond to close the gaps.

Enhancing learning, improving data

From information gathered in household surveys to pixels captured by satellite images, data can inform policies and spur economic activity, serving as a powerful weapon in the fight against poverty. More data is available today than ever before, yet its value is largely untapped. Data is also a double-edged sword, requiring a social contract that builds trust by protecting people against misuse and harm, and works toward equal access and representation.

Investing in preparedness and prevention

The COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated that years of progress in reducing poverty can quickly disappear when a crisis strikes. Prevention measures often have low political payoff, with little credit given for disasters averted. Over time, populations with no lived experience of calamity can become complacent, presuming that such risks have been eliminated or can readily be addressed if they happen. COVID-19, together with climate change and enduring conflicts, reminds us of the importance of investing in preparedness and prevention measures comprehensively and proactively.

Expanding cooperation and coordination

Contributing to and maintaining public goods require extensive cooperation and coordination. This is crucial for promoting widespread learning and improving the data-driven foundations of policymaking. It is also important for forming a sense of shared solidarity during crises and ensuring that the difficult policy choices by officials are both trusted and trustworthy.

Overall, with more than 60 percent of the world’s extreme poor living in middle-income countries, we cannot focus solely on low-income countries if we want to end extreme poverty. We need to focus on the poorest people, regardless of where they live, and work with countries at all income levels to invest in their well-being and their future.

The goal to end extreme poverty works hand in hand with the World Bank Group’s goal to promote shared prosperity. Boosting shared prosperity broadly translates into improving the welfare of the least well-off in each country and includes a strong emphasis on tackling persistent inequalities that keep people in poverty from generation to generation.

Our work at the World Bank Group is based on strong country-led programs to improve living conditions—to drive growth, raise median incomes, create jobs, fully incorporate women and young people into economies, address environmental and climate challenges, and support stronger, more stable economies for everyone.

We continue to work closely with countries to help them find the best ways to improve the lives of their least advantaged citizens.

Last Updated: Oct 17, 2023

How the Pandemic Drove Increases in Poverty | Poverty & Shared Prosperity 2022

Around the bank group.

Find out what the World Bank Group's branches are doing to reduce poverty.

STAY CONNECTED

COVID-19 Dealt a Historic Blow to Poverty Reduction

The 2022 Poverty and Prosperity Report provides the first comprehensive analysis of the pandemic’s toll on poverty in developing countries and of the role of fiscal policy in protecting vulnerable groups.

Umbrella Facility for Poverty and Equity

The Umbrella Facility for Poverty and Equity (UFPE) is the first global trust fund to support the cross-cutting poverty and equity agenda.

IDA: Our Fund for the Poorest

The International Development Association (IDA) aims to reduce poverty by providing funding for programs that boost economic growth.

High-Frequency Monitoring Systems to Track the Impacts of COVID-19

The World Bank and partners are monitoring the crisis and the socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19 through a series of high-frequency phone surveys.

Poverty Podcast

Join us and poverty specialists as we explore the latest data and research on poverty reduction, shared prosperity, and equity around the globe in this new World Bank Group podcast series.

Stepping Up the Fight Against Extreme Poverty

To avert the risk of more backsliding, policymakers must put everything they can into the effort to end extreme poverty.

Additional Resources

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

By: Joe Hasell , Max Roser , Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Pablo Arriagada

Global poverty is one of the most pressing problems that the world faces today. The poorest in the world are often undernourished , without access to basic services such as electricity and safe drinking water ; they have less access to education , and suffer from much poorer health .

In order to make progress against such poverty in the future, we need to understand poverty around the world today and how it has changed.

On this page you can find all our data, visualizations and writing relating to poverty. This work aims to help you understand the scale of the problem today; where progress has been achieved and where it has not; what can be done to make progress against poverty in the future; and the methods behind the data on which this knowledge is based.

Key Insights on Poverty

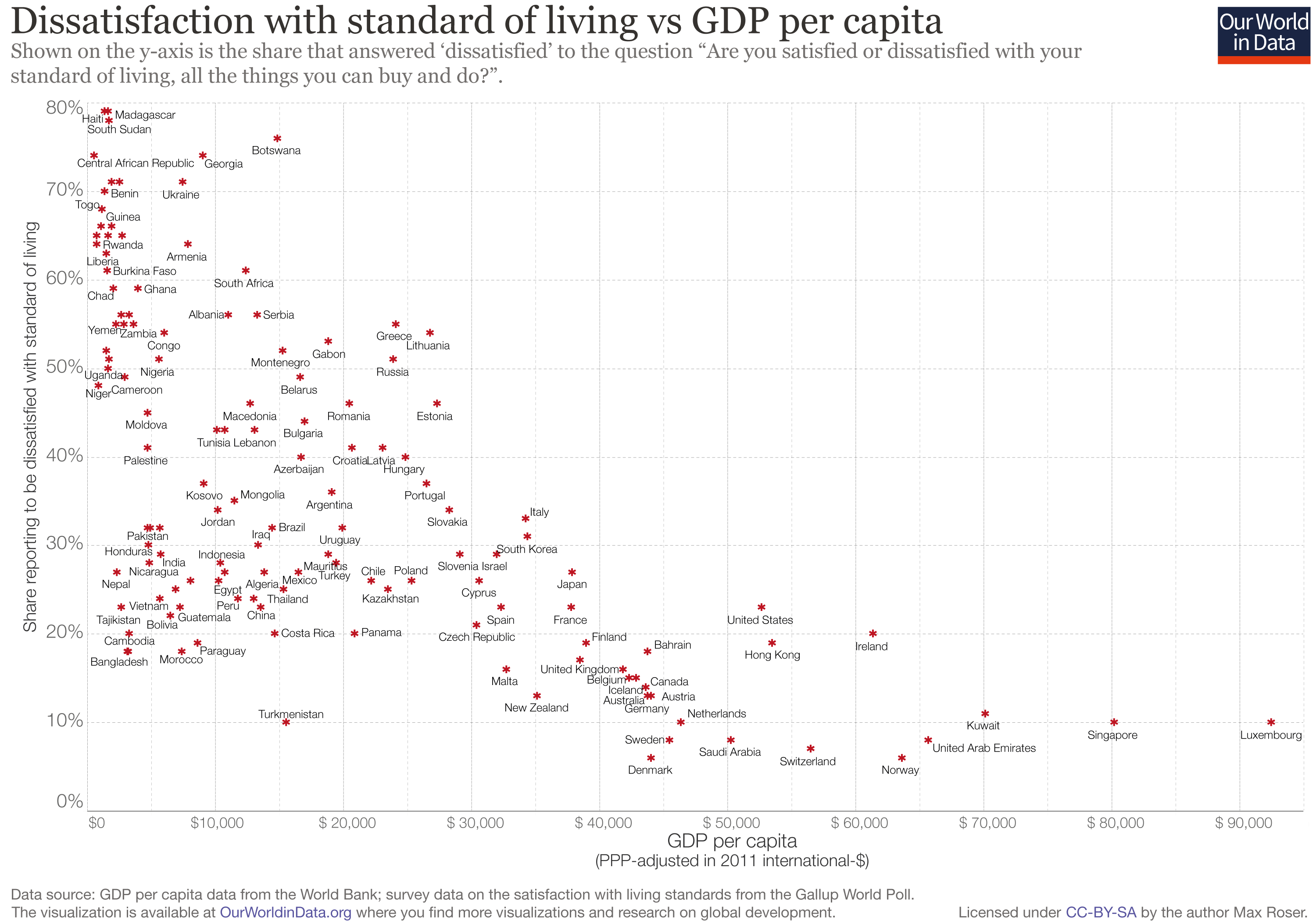

Measuring global poverty in an unequal world.

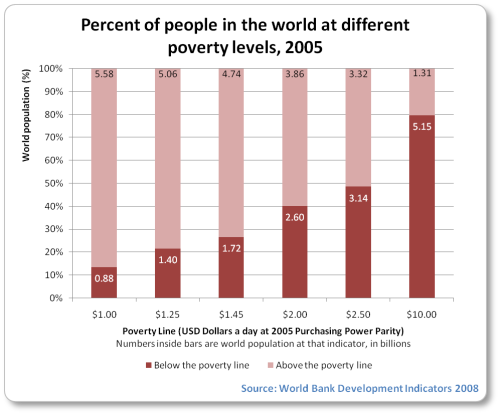

There is no single definition of poverty. Our understanding of the extent of poverty and how it is changing depends on which definition we have in mind.

In particular, richer and poorer countries set very different poverty lines in order to measure poverty in a way that is informative and relevant to the level of incomes of their citizens.

For instance, while in the United States a person is counted as being in poverty if they live on less than roughly $24.55 per day, in Ethiopia the poverty line is set more than 10 times lower – at $2.04 per day. You can read more about how these comparable national poverty lines are calculated in this footnote. 1

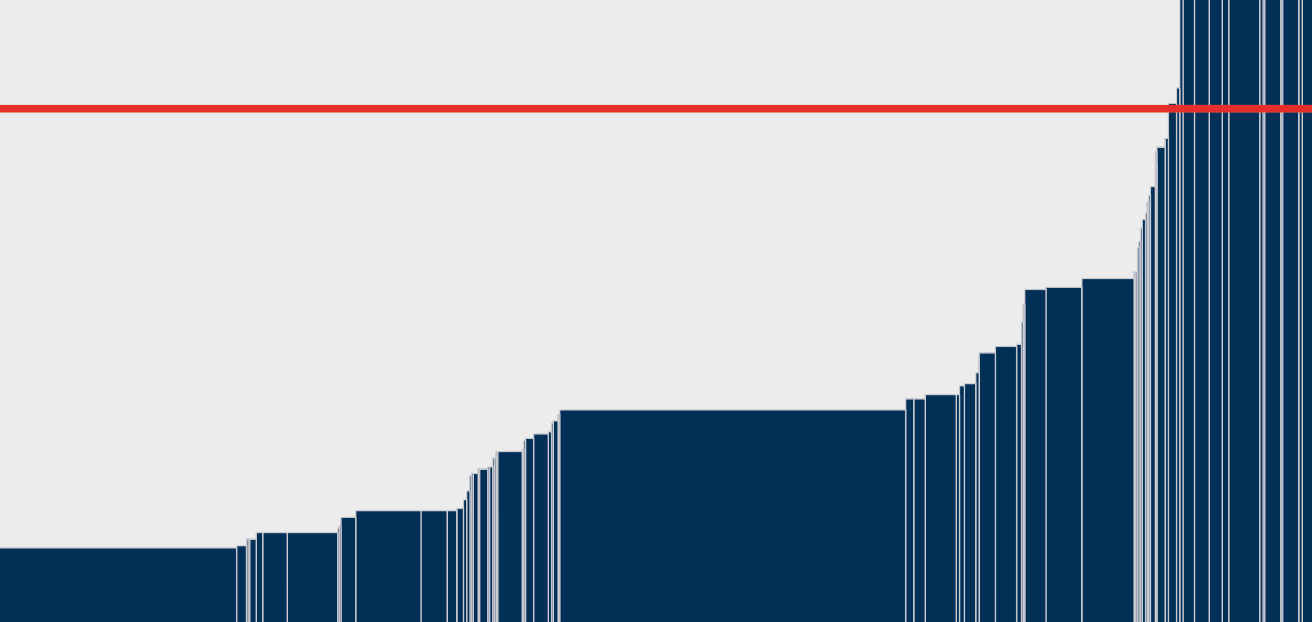

To measure poverty globally, however, we need to apply a poverty line that is consistent across countries.

This is the goal of the International Poverty Line of $2.15 per day – shown in red in the chart – which is set by the World Bank and used by the UN to monitor extreme poverty around the world.

We see that, in global terms, this is an extremely low threshold indeed – set to reflect the poverty lines adopted nationally in the world’s poorest countries. It marks an incredibly low standard of living – a level of income much lower than just the cost of a healthy diet .

From $1.90 to $2.15 a day: the updated International Poverty Line

What you should know about this data.

- Global poverty data relies on national household surveys that have differences affecting their comparability across countries or over time. Here the data for the US relates to incomes and the data for other countries relates to consumption expenditure. 2

- The poverty lines here are an approximation of national definitions of poverty, made in order to allow comparisons across the countries. 1

- Non-market sources of income, including food grown by subsistence farmers for their own consumption, are taken into account. 3

- Data is measured in 2017 international-$, which means that inflation and differences in the cost of living across countries are taken into account. 4

Global extreme poverty declined substantially over the last generation

Over the past generation extreme poverty declined hugely. This is one of the most important ways our world has changed over this time.

There are more than a billion fewer people living below the International Poverty Line of $2.15 per day today than in 1990. On average, the number declined by 47 million every year, or 130,000 people each day. 5

The scale of global poverty today, however, remains vast. The latest global estimates of extreme poverty are for 2019. In that year the World Bank estimates that around 650 million people – roughly one in twelve – were living on less than $2.15 a day.

Extreme poverty: how far have we come, how far do we still have to go?

- Extreme poverty here is defined according to the UN’s definition of living on less than $2.15 a day – an extremely low threshold needed to monitor and draw attention to the living conditions of the poorest around the world. Read more in our article, From $1.90 to $2.15 a day: the updated International Poverty Line .

- Global poverty data relies on national household surveys that have differences affecting their comparability across countries or over time. 2

- Surveys are less frequently available in poorer countries and for earlier decades. To produce regional and global poverty estimates, the World Bank collates the closest survey for each country and projects the data forward or backwards to the year being estimated. 6

- Data is measured in 2017 international-$, which means that inflation and differences in the cost of living across countries are taken into account . 4

The pandemic pushed millions into extreme poverty

Official estimates for global poverty over the course of the Coronavirus pandemic are not yet available.

But it is clear that the global recession it brought about has had a terrible impact on the world’s poorest.

Preliminary estimates produced by researchers at the World Bank suggest that the number of people in extreme poverty rose by around 70 million in 2020 – the first substantial rise in a generation – and remains around 70-90 million higher than would have been expected in the pandemic’s absence. On these preliminary estimates, the global extreme poverty rate rose to around 9% in 2020. 7

- Figures for 2020-2022 are preliminary estimates and projections by World Bank researchers, based on economic growth forecasts. The pre-pandemic projection is based on growth forecasts prior to the pandemic. You can read more about this data and the methods behind it in the World Bank’s Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2022 report. 8

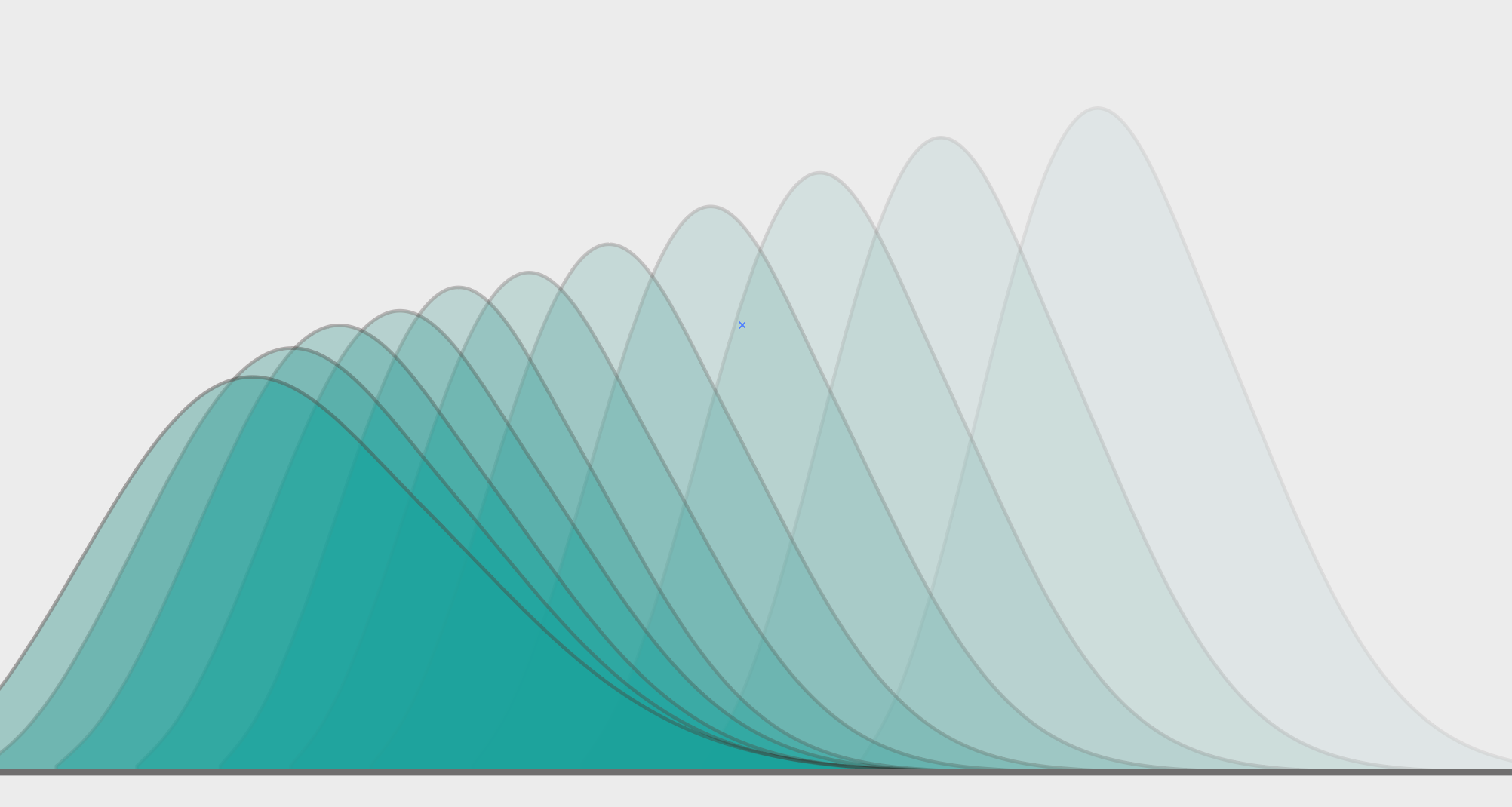

Hundreds of millions will remain in extreme poverty on current trends

Extreme poverty declined during the last generation because the majority of the poorest people on the planet lived in countries with strong economic growth – primarily in Asia.

The majority of the poorest now live in Sub-Saharan Africa, where weaker economic growth and high population growth in many countries has led to a rising number of people living in extreme poverty.

The chart here shows projections of global extreme poverty produced by World Bank researchers based on economic growth forecasts. 9

A very bleak future is ahead of us should such weak economic growth in the world’s poorest countries continue – a future in which extreme poverty is the reality for hundreds of millions for many years to come.

- The extreme poverty estimates and projections shown here relate to a previous release of the World Bank’s poverty and inequality data in which incomes are expressed in 2011 international-$. The World Bank has since updated its methods, and now measures incomes in 2017 international-$. As part of this change, the International Poverty Line used to measure extreme poverty has also been updated: from $1.90 (in 2011 prices) to $2.15 (in 2017 prices). This has had little effect on our overall understanding of poverty and inequality around the world. You can read more about this change and how it affected the World Bank estimates of poverty in our article From $1.90 to $2.15 a day: the updated International Poverty Line .

- Figures for 2018 and beyond are preliminary estimates and projections by Lakner et al. (2022), based on economic growth forecasts. You can read more about this data and the methods behind it in the related blog post. 10

- Data is measured in 2011 international-$, which means that inflation and differences in the cost of living across countries are taken into account. 4

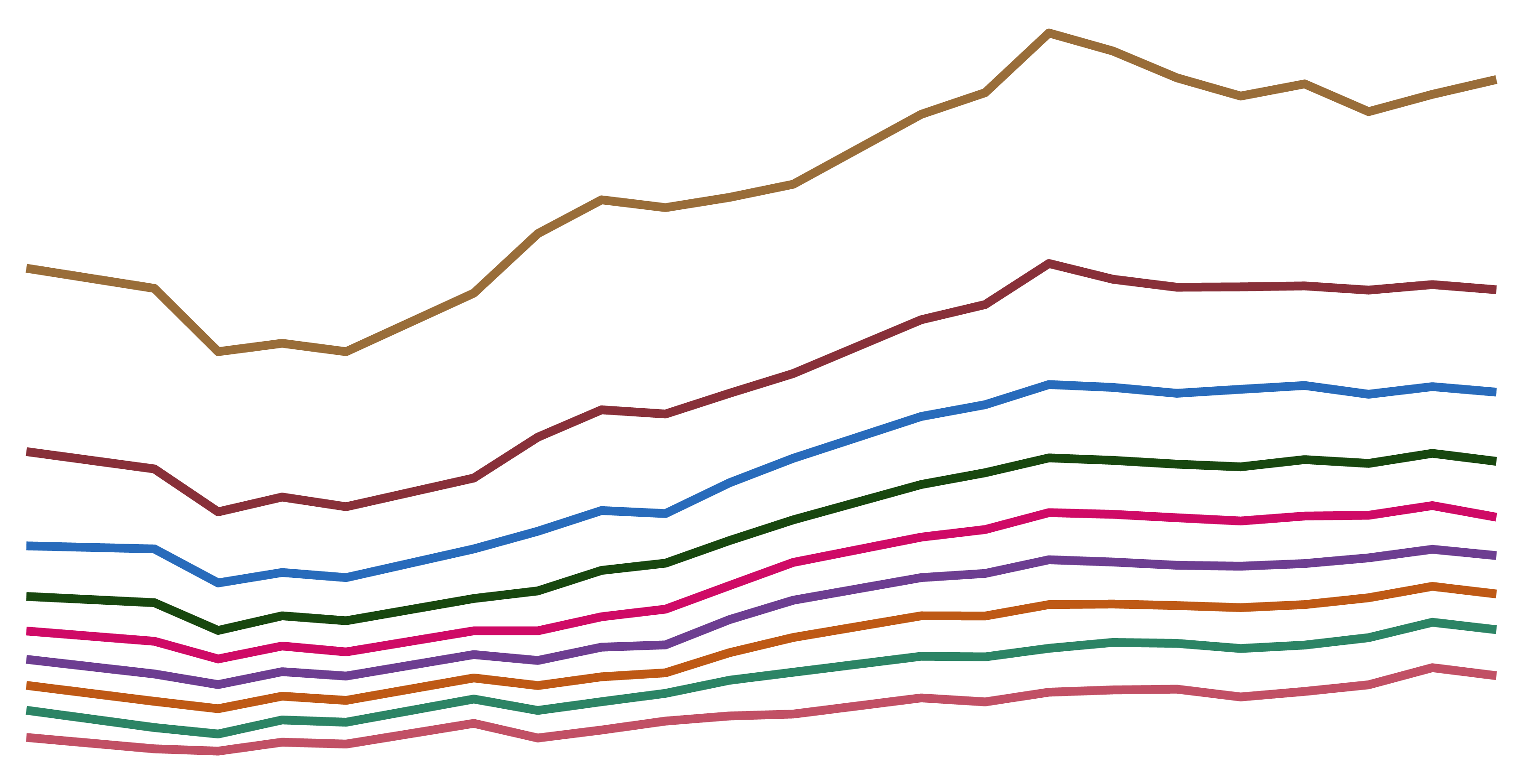

The rapid progress seen in many countries shows an end to poverty is possible

Each of the countries shown in the chart achieved large declines in extreme poverty over the last generation. 11

The fact that rapid progress against poverty has been achieved in many places is one of the most important lessons we can learn from the available data on extreme poverty.

For those who are not aware of such progress – which is the majority of people – it would be easy to make the mistake of believing that poverty is inevitable and that action to tackle poverty is hence doomed to fail.

The huge progress seen in so many places shows that this view is incorrect.

Interactive visualization requires JavaScript.

After 200 years of progress the fight against global poverty is just beginning

Over the past two centuries the world made good progress against extreme poverty. But only very recently has poverty fallen at higher poverty lines.

Global poverty rates at these higher lines remain very high:

- 25% of the world lives on less than $3.65 per day – a poverty line broadly reflective of the lines adopted in lower-middle income countries.

- 47% of the world lives on less than $6.85 per day – a poverty line broadly reflective of the lines adopted in upper-middle income countries.

- 84% live on less than $30 per day – a poverty line broadly reflective of the lines adopted in high income countries. 12

Economic growth over the past two centuries has allowed the majority of the world to leave extreme poverty behind. But by the standards of today’s rich countries, the world remains very poor. If this should change, the world needs to achieve very substantial economic growth further still.

The history of the end of poverty has just begun

How much economic growth is necessary to reduce global poverty substantially?

- The data from 1981 onwards is based on household surveys collated by the World Bank. Earlier figures are from Moatsos (2021), who extends the series backwards based on historical reconstructions of GDP per capita and inequality data. 13

- All data is measured in international-$ which means that inflation and differences in purchasing power across countries are taken into account. 4

- The World Bank data for the higher poverty lines is measured in 2017 international-$. Recently, the World Bank updated its methodology having previously used 2011 international-$ to measure incomes and set poverty lines. The Moatsos (2021) historical series is based on the previously-used World Bank definition of extreme poverty – living on less than $1.90 a day when measured in 2011 international-$. This is broadly equivalent to the current World Bank definition of extreme poverty – living on less than $2.15 a day when measured in 2017 international-$. You can read more about this update to the World Bank’s methodology and how it has affected its estimates of poverty in our article From $1.90 to $2.15 a day: the updated International Poverty Line .

- The global poverty data shown from 1981 onwards relies on national household surveys that have differences affecting their comparability across countries or over time. 2

- Such surveys are less frequently available in poorer countries and for earlier decades. To produce regional and global poverty estimates, the World Bank collates the closest survey for each country and projects the data forward or backwards to the year being estimated. 6

- Non-market sources of income, including food grown by subsistence farmers for their own consumption, are taken into account. This is also true of the historical data – in producing historical estimates of GDP per capita on which these long-run estimates are based, economic historians take into account such non-market sources of income, as we discuss further in our article How do we know the history of extreme poverty?

Explore Data on Poverty

About this data.

All the data included in this explorer is available to download in GitHub , alongside a range of other poverty and inequality metrics.

Where is this data sourced from?

This data explorer is collated and adapted from the World Bank’s Poverty and Inequality Platform (PIP).

The World Bank’s PIP data is a large collection of household surveys where steps have been taken by the World Bank to harmonize definitions and methods across countries and over time.

About the comparability of household surveys

There is no global survey of incomes. To understand how incomes across the world compare, researchers need to rely on available national surveys.

Such surveys are partly designed with cross-country comparability in mind, but because the surveys reflect the circumstances and priorities of individual countries at the time of the survey, there are some important differences.

Income vs expenditure surveys

One important issue is that the survey data included within the PIP database tends to measure people’s income in high-income countries, and people’s consumption expenditure in poorer countries.

The two concepts are closely related: the income of a household equals their consumption plus any saving, or minus any borrowing or spending out of savings.

One important difference is that, while zero consumption is not a feasible value – people with zero consumption would starve – a zero income is a feasible value. This means that, at the bottom end of the distribution, income and consumption can give quite different pictures about a person’s welfare. For instance, a person dissaving in retirement may have a very low, or even zero, income, but have a high level of consumption nevertheless.

The gap between income and consumption is higher at the top of this distribution too, richer households tend to save more, meaning that the gap between income and consumption is higher at the top of this distribution too. Taken together, one implication is that inequality measured in terms of consumption is generally somewhat lower than the inequality measured in terms of income.

In our Data Explorer of this data there is the option to view only income survey data or only consumption survey data, or instead to pool the data available from both types of survey – which yields greater coverage.

Other comparability issues

There are a number of other ways in which comparability across surveys can be limited. The PIP Methodology Handbook provides a good summary of the comparability and data quality issues affecting this data and how it tries to address them.

In collating this survey data the World Bank takes a range of steps to harmonize it where possible, but comparability issues remain. These affect comparisons both across countries and within individual countries over time.

To help communicate the latter, the World Bank produces a variable that groups surveys within each individual country into more comparable ‘spells’. Our Data Explorer provides the option of viewing the data with these breaks in comparability indicated, and these spells are also indicated in our data download .

Global and regional poverty estimates

Along with data for individual countries, the World Bank also provides global and regional poverty estimates which aggregate over the available country data.

Surveys are not conducted annually in every country however – coverage is generally poorer the further back in time you look, and remains particularly patchy within Sub-Saharan Africa. You can see that visualized in our chart of the number of surveys included in the World Bank data by decade.

In order to produce global and regional aggregate estimates for a given year, the World Bank takes the surveys falling closest to that year for each country and ‘lines-up’ the data to the year being estimated by projecting it forwards or backwards.

This lining-up is generally done on the assumption that household incomes or expenditure grow in line with the growth rates observed in national accounts data. You can read more about the interpolation methods used by the World Bank in Chapter 5 of the Poverty and Inequality Platform Methodology Handbook.

How does the data account for inflation and for differences in the cost of living across countries?

To account for inflation and price differences across countries, the World Bank’s data is measured in international dollars. This is a hypothetical currency that results from price adjustments across time and place. It is defined as having the same purchasing power as one US-$ would in the United States in a given base year. One int.-$ buys the same quantity of goods and services no matter where or when it is spent.

There are many challenges to making such adjustments and they are far from perfect. Angus Deaton ( Deaton, 2010 ) provides a good discussion of the difficulties involved in price adjustments and how this relates to global poverty measurement.

But in a world where price differences across countries and over time are large it is important to attempt to account for these differences as well as possible, and this is what these adjustments do.

In September 2022, the World Bank updated its methodology, and now uses international-$ expressed in 2017 prices – updated from 2011 prices. This has had little effect on our overall understanding of poverty and inequality around the world. But poverty estimates for particular countries vary somewhat between the old and updated methodology. You can read more about this update in our article From $1.90 to $2.15 a day: the updated International Poverty Line .

To allow for comparisons with the official data now expressed in 2017 international-$ data, the World Bank continues to release its poverty and inequality data expressed in 2011 international-$ as well. We have built a Data Explorer to allow you to compare these, and we make all figures available in terms of both sets of prices in our data download .

Absolute vs relative poverty lines

This dataset provides poverty estimates for a range of absolute and relative poverty lines.

An absolute poverty line represents a fixed standard of living; a threshold that is held constant across time. Within the World Bank’s poverty data, absolute poverty lines also aim to represent a standard of living that is fixed across countries (by converting local currencies to international-$). The International Poverty Line of $2.15 per day (in 2017 international-$) is the best known absolute poverty line and is used by the World Bank and the UN to measure extreme poverty around the world.

The value of relative poverty lines instead rises and falls as average incomes change within a given country. In most cases they are set at a certain fraction of the median income. Because of this, relative poverty can be considered a metric of inequality – it measures how spread out the bottom half of the income distribution is.

The idea behind measuring poverty in relative terms is that a person’s well-being depends not on their own absolute standard of living but on how that standard compares with some reference group, or whether it enables them to participate in the norms and customs of their society. For instance, joining a friend’s birthday celebration without shame might require more resources in a rich society if the norm is to go for an expensive meal out, or give costly presents.

Our dataset includes three commonly-used relative poverty lines: 40%, 50%, and 60% of the median.

Such lines are most commonly used in rich countries, and are the main way poverty is measured by the OECD and the European Union . More recently, relative poverty measures have come to be applied in a global context. The share of people living below 50 per cent of median income is, for instance, one of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal indicators . And the World Bank now produces estimates of global poverty using a Societal Poverty Line that combines absolute and relative components.

When comparing relative poverty rates around the world, however, it is important to keep in mind that – since average incomes are so far apart – such relative poverty lines relate to very different standards of living in rich and poor countries.

Does the data account for non-market income, such as food grown by subsistence farmers?

Many poor people today, as in the past, rely on subsistence farming rather than a monetary income gained from selling goods or their labor on the market. To take this into account and make a fair comparison of their living standards, the statisticians that produce these figures estimate the monetary value of their home production and add it to their income/expenditure.

Research & Writing

Despite making immense progress against extreme poverty, it is still the reality for every tenth person in the world.

$2.15 a day: the updated International Poverty Line

What does the World Bank’s updated methods mean for our understanding of global poverty?

Global poverty over the long-run

How do we know the history of extreme poverty?

Joe Hasell and Max Roser

Breaking out of the Malthusian trap: How pandemics allow us to understand why our ancestors were stuck in poverty

The short history of global living conditions and why it matters that we know it

Poverty & economic growth.

The economies that are home to the poorest billions of people need to grow if we want global poverty to decline substantially

Global poverty in an unequal world: Who is considered poor in a rich country? And what does this mean for our understanding of global poverty?

What do poor people think about poverty?

More articles on poverty.

Three billion people cannot afford a healthy diet

Hannah Ritchie

Homelessness and poverty in rich countries

Esteban Ortiz-Ospina

OWID Data Collection: Inequality and Poverty

Joe Hasell and Pablo Arriagada

Interactive Charts on Poverty

Official definitions of poverty in different countries are often not directly comparable due to the different ways poverty is measured. For example, countries account for the size of households in different ways in their poverty measures.

The poverty lines shown here are an approximation of national definitions, harmonized to allow for comparisons across countries. For all countries apart from the US, we take the harmonized poverty line calculated by Jolliffe et al. (2022). These lines are calculated as the international dollar figure which, in the World Bank’s Poverty and Inequality Platform (PIP) data, yields the same poverty rate as the officially reported rate using national definitions in a particular year (around 2017).

For the US, Jolliffe et al. (2022) use the OECD’s published poverty rate – which is measured against a relative poverty line of 50% of the median income. This yields a poverty line of $34.79 (measured using 2017 survey data). This however is not the official definition of poverty adopted in the US. We calculated an alternative harmonized figure for the US national poverty using the same method as Jolliffe et al. (2022), but based instead on the official 2019 poverty rate – as reported by the U.S. Census Bureau.