Home > Blog > Tips for Online Students > Tips for Students > What Is ELL In Education And Why It’s Important

Tips for Online Students , Tips for Students

What Is ELL In Education And Why It’s Important

Updated: June 19, 2024

Published: June 10, 2020

Ever heard of the term ELL and wondered, “What is ELL?” It sounds a lot like ESL, and it’s related! ELL stands for English language learners. The term is slightly different from ESL though, and we will explain how and why it was created.

The importance of knowing English for education and business is a high priority and expanding need in the global community. Second only to Mandarin Chinese, English is the most spoken language in the world. That’s why a lot of non-native English speakers become English language learners (ELL).

If you fall into this category as a learner or you are an ELL teacher who helps students learn English, this article is filled with ELL strategies to help!

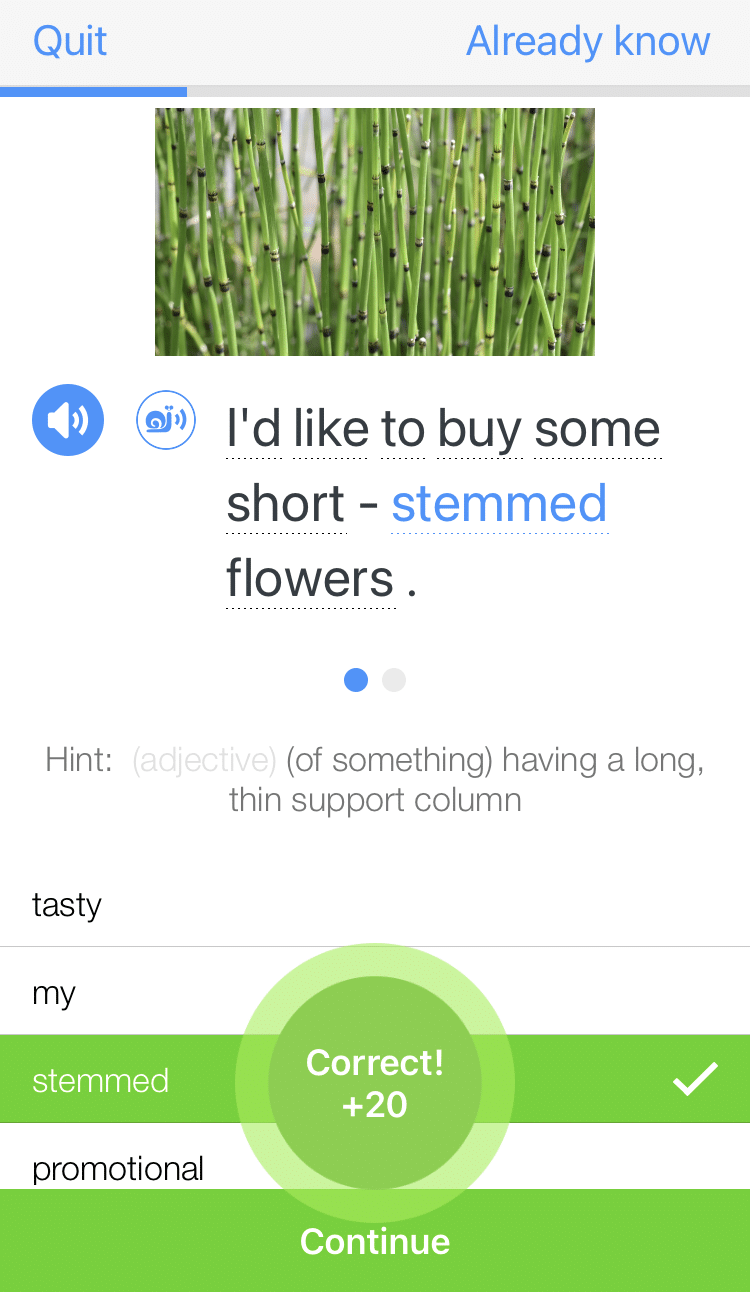

Photo by Taylor Wilcox on Unsplash

What is ell.

An ELL is defined as anyone who does not learn English as their first and primary language. According to the National Education Association , ELL learners are the fastest growing student population. It’s estimated that roughly one-fourth of all students in public school by 2025 will be ELLs.

The most common native languages that ELL children speak include: Spanish, Arabic, Vietnamese, Chinese, Somali, Russian, Haitian, and Hmong. While some students may speak English on a basic level, these students need extra help in learning English academically.

The Evolution Of “ELL”

The term ELL originated as an alternative to ESL (English as a Second Language). In 2011, people at the Fresh Voices from Long Journeys: Immigrant and Refugee Students conference in Canada brought it to the world’s attention that some English language learners are not learning English as their second language. That makes the term “ESL” technically incorrect.

As such, ELL is becoming a more popular and politically correct term to ESL, especially by educators. Furthermore, ELL also encompasses students who are learning English as an academic necessity. For example, ELL may refer to a student’s academic performance in English-language subject classes.

Objectives Of ELL

ELL objectives may vary depending on the program or country in which a student is learning English.

However, at the heart of ELL stands the same goal — to prepare students to speak English as quickly and proficiently as possible. The objective is so students can not only excel in academics, but they can also partake in social activities and have the ability to communicate with their peers and teachers.

Taking ELL a step beyond primary and secondary school is the objective for students to perform well in institutes of higher education. For the most part, proficiency in English is a requirement for many schools.

At the University of the People, admissions requirements are relatively low compared to most other institutions. However, one of the two requirements is that students have proficiency in English, and that’s because all classes are taught online in English.

When students are able to speak English from a young age, it will set them up for more opportunities in education and careers down the line.

7 Types Of ELL Programs

Each program that offers ELL can choose from a variety of ways to initiate the courses. These may span the following:

1. The ESL Pull-Out Program

Students remain in the same academic classes as their native English speaking peers, but at a certain point, they are “pulled out” to go learn English separately.

2. Content-Based ESL Program

The goal is to incorporate English at an understandable level within context to teach. For example, teachers may use visual aids and gestures to teach vocabulary and concepts.

3. English-Language Instruction Program

When there are students who speak many different languages, the teacher will solely teach in English.

4. Bilingual Instructional Program

As the name implies, classes are taught in both the student’s native language as well as English. The best scenario to implement this program is when teachers are in a classroom in which the bulk of students speak the same native language.

5. Transitional/Early-Exit Program

With the goal to have students learning entirely in English as quickly as possible, this instruction is a blend. It starts off by first helping students understand concepts and fluency by teaching in their native language. Then, once concepts are mastered, teachers will switch to instruction in English only.

6. Maintenance/Late-Exit Program

As the antithesis of the aforementioned style of teaching, the late-exit program maintains teaching in a student’s native language until they are considered fluent in English. Only then will instruction switch to English. In this way, students can maintain fluency in multiple languages concurrently.

7. Two-Way Bilingual Program

Teachers who are bilingual have the opportunity to teach in both languages. There’s a 50/50 balance in instruction for both native English speakers and English language learning students.

Photo by ThisisEngineering RAEng on Unsplash

What is an esl teacher.

To make any of these programs function properly, teachers must motivate their students. While that could be said about any form of education, ESL teachers play a special role for ELL students.

ESL teachers are those who connect non-native speakers to English language learning. They support ELL students and connect them to a new culture and way of learning.

6 Strategies For Helping ELL Students In The Classroom

As an ESL teacher, you play a pivotal role in the success of your ELL students. Not only are you their primary source to learn a new language, but you also are opening the door to a new world of opportunities and connections.

There are various strategies for how to best work with ELL students in any classroom settings. Here are some best practices:

1. Cultural Responsiveness

Teaching English doesn’t negate the fact that every language is important and useful to the world. ESL teachers can help a student acclimate by also paying homage to their culture. When a student feels seen and understood, they will be more likely to take risks, both emotionally and intellectually.

2. Teach Language Across Subjects

English spans every subject. As such, teaching English in isolation as it pertains to language alone is insufficient. You can incorporate English language learners across subjects while still introducing new words, concepts, and understanding.

3. Productive Language

It’s common for students learning a new language to only want to listen. However, productive language skills like reading, writing, and speaking should be introduced from the get go. You can help students set up sentences by offering fill in the blank versions so that they can use context clues to write or speak in complete sentences, even if they just know a few words to begin.

4. Speak Slowly

It’s natural to expect immediate responses when teaching an engaged classroom. However, when you work with students who are learning a new language, it’s important to practice patience and speak slowly. Additionally, give an extra few seconds for students to respond to questions.

5. Multiple Modalities

Incorporate various ways of teaching and student engagement throughout a lesson. One specific strategy to try is expressed through the acronym “QSSSA.” This stands for:

- Question: Ask a question

- Signal: Gesture that it’s a student’s turn to answer the question (try a thumbs up, or a light tap on the shoulder, for example)

- Stem: Begin the answer for the student and then let them fill in the rest of the sentence

- Share: Allow a student to respond and fill in the blank

- Assess: Only provide feedback or a response after the student has completed their thought

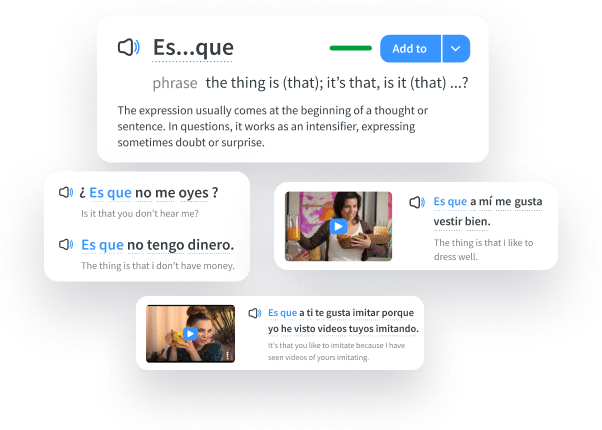

6. Technology

It should go without saying that technology can be a great resource and friend to both ESL teachers and ELL students. From using tools like Google Translate to allowing students to play video games and go online in English, the various modalities in which technology can help a student learn are seemingly infinite.

Teaching ELL Students: 3 Things To Know

When teaching and learning a new language, there are obvious challenges that will arise. However, it’s important to keep in mind that it’s a process and all forms of progress should be celebrated.

Here are some expectations that are likely to occur and ways to manage them effectively:

1. A Silent Period

Many students take time to adjust to speaking or learning in a new language. As such, they may be understanding the curriculum, but they are hesitant to speak. Be patient with silent periods.

2. Develop Non-Verbal Communication

To assist even more so during silent periods, try to communicate non-verbally. Allow students to play charades, gesture or even draw responses to questions they know answers to.

3. Utilize Peers

A nice way to help ELLs integrate into the classroom is to assign a native-English-speaking buddy to be by their side. This way, they can both form friendships and learn from someone who is their peer.

Final Tips: Supporting ELL Students In The Classroom

Try these final recommendations to better support your ELL students:

- Use visuals

- Assign group work

- Honor their silent period

- Practice scaffolding education

- Use sentence frames and stems

- Incorporate cultural vocabulary

- Learn about their native culture and show appreciation

- Listen carefully and patiently

The Wrap Up

Learning English or any new language can be challenging and overwhelming. But, as an ESL teacher, you have the power in your hands to support English language learners by utilizing these best practices.

Strategies for ELL students will be increasingly needed as the number of ELL students continues to grow. Regardless of the type of ELL program initiated, students should feel supported and heard while increasing their English proficiency. You can make all the difference!

In this article

At UoPeople, our blog writers are thinkers, researchers, and experts dedicated to curating articles relevant to our mission: making higher education accessible to everyone. Read More

When English becomes the global language of education we risk losing other – often better – ways of learning

Professor and Dean of Education, Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington

Adjunct Research Fellow Victoria University of Wellington; Head of the Quality Assurance Institute and Senior Lecturer, Universitas Islam Negeri Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta

Disclosure statement

Muhammad Zuhdi terafiliasi dengan UIN Syarif Hidayatullah Jakarta.

Stephen Dobson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Te Herenga Waka — Victoria University of Wellington provides funding as a member of The Conversation NZ.

Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

- Bahasa Indonesia

The English language in education today is all-pervasive. “Hear more English, speak more English and become more successful” has become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Some say it’s already a universal language, ahead of other mother tongues such as Arabic, Chinese, Russian, Spanish or French. In reality, of course, this has been centuries in the making. Colonial conquest and global trade routes won the hearts and minds of foreign education systems.

These days, the power of English (or the versions of English spoken in different countries) has become accepted wisdom, used to justify the globalisation of education at the cost of existing systems in non-English-speaking countries.

The British Council exemplifies this, with its global presence and approving references to the “ English effect ” on educational and employment prospects.

English as a passport to success

In non-English countries the packaging of English and its promise of success takes many forms. Instead of being integrated into (or added to) national teaching curricula, English language learning institutes, language courses and international education standards can dominate whole systems.

Among the most visible examples are Cambridge Assessment International Education and the International Baccalaureate (which is truly international and, to be fair, also offered in French and Spanish).

Read more: Beyond the black hole of global university rankings: rediscovering the true value of knowledge and ideas

Schools in non-English-speaking countries attract globally ambitious parents and their children with a mix of national and international curricula, such as the courses offered by the Singapore Intercultural School across South-East Asia.

Language and the class divide

The love of all things English begins at a young age in non-English-speaking countries, promoted by pop culture, Hollywood movies, fast-food brands, sports events and TV shows.

Later, with English skills and international education qualifications from high school, the path is laid to prestigious international universities in the English-speaking world and employment opportunities at home and abroad.

But those opportunities aren’t distributed equally across socioeconomic groups. Global education in English is largely reserved for middle-class students.

This is creating a divide between those inside the global English proficiency ecosystem and those relegated to parts of the education system where such opportunities don’t exist.

For the latter there is only the national education curriculum and the lesson that social mobility is a largely unattainable goal.

The Indonesian experience

Indonesia presents a good case study. With a population of 268 million, access to English language curricula has mostly been limited to urban areas and middle-class parents who can afford to pay for private schools.

At the turn of this century, all Indonesian districts were mandated to have at least one public school offering a globally recognised curriculum in English to an international standard. But in 2013 this was deemed unconstitutional because equal educational opportunity should exist across all public schools.

Read more: Lessons taught in English are reshaping the global classroom

Nevertheless, today there are 219 private schools offering at least some part of the curriculum through Cambridge International, and 38 that identify as Muslim private schools. Western international curricula remain influential in setting the standard for what constitutes quality education.

In Muslim schools that have adopted globally recognised curricula in English, there is a tendency to over-focus on academic performance. Consequently, the important Muslim value of تَرْبِيَة ( Tarbiya ) is downplayed.

Encompassing the flourishing of the whole child and the realisation of their potential, Tarbiya is a central pillar in Muslim education. Viewed like this, schooling that concentrates solely on academic performance fails in terms of both culture and faith.

Learning is about more than academic performance

Academic performance measured by knowledge and skill is, of course, still important and a source of personal fulfilment. But without that cultural balance and the nurturing of positive character traits, we argue it lacks deeper meaning.

Read more: The top ranking education systems in the world aren't there by accident. Here's how Australia can climb up

A regulation issued by the Indonesian minister of education in 2018 underlined this. It listed a set of values and virtues that school education should foster: faith, honesty, tolerance, discipline, hard work, creativity, independence, democracy, curiosity, nationalism, patriotism, appreciation, communication, peace, a love of reading, environmental awareness, social awareness and responsibility.

These have been simplified to five basic elements of character education: religion, nationalism, Gotong Royong (collective voluntary work), independence and integrity.

These are not necessarily measurable by conventional, Western, English-speaking and empirical means. Is it time, then, to reconsider the internationalising of education (and not just in South-East Asia)? Has it gone too far, at least in its English form?

Isn’t it time to look closely at other forms of education in societies where English is not the mother tongue? These education systems are based on different values and they understand success in different ways.

It’s unfortunate so many schools view an English-speaking model as the gold standard and overlook their own local or regional wisdoms. We need to remember that encouraging young people to join a privileged English-speaking élite educated in foreign universities is only one of many possible educational options.

- New Zealand

- English teaching

Service Delivery Consultant

Newsletter and Deputy Social Media Producer

College Director and Principal | Curtin College

Head of School: Engineering, Computer and Mathematical Sciences

Educational Designer

- Utility Menu

Language for Learning: Towards a language learning theory relevant for education

The importance of language in school and society.

L4L theory of language learning

Languages are always learned in specific socio-cultural contexts. Learners do not just learn “language,” they learn particular ways of using language in particular contexts. This is the case for multilingual and monolingual learners.

Our L4L theory of language learning “integrates insights from ethnographic research on language and literacy (Heath, 1983; Levine, et al., 1996; Ochs, 1988), pragmatic development studies (Blum-Kulka, 2008; Ninio & Snow, 1996) and functional linguistics research (Berman & Ravid, 2009; Schleppegrell, 2004) to conceptualize language learning as inseparable from context… Three key developmental implications emerge from these combined insights. • First, language development continues throughout adolescence and, under normal circumstances, language learning continues for as long as learners expand the language-mediated social contexts that they navigate. • Second, being a skilled language user in one social context does not guarantee linguistic dexterity in a different social context. Whereas speakers are enculturated at home into the language of face-to-face interaction, which typically prepares them well for colloquial conversations in their respective communities, many adolescents have encountered limited opportunities to learn school-relevant language practices and, consequently, academic language poses higher challenges for them (Cazden, 2002; Cummins, 2000; Heath, 2012). • Third, language is a powerful socializer: by learning language, children also learn how to interact with others, how to comprehend, and how to learn in ways that are culturally shaped (Heath, 1983; Ochs, 1988).” (Uccelli, 2019; Uccelli, Phillips Galloway & Qin, 2020))

Extended talk supports the language of school literacy & learning

“In a socio-cultural pragmatics-based framework, language and literacy proficiencies are conceptualized as the result, to a large extent, of an individual’s history of participation in specific contexts and socio-cultural discourses” (Uccelli, 2019)

Publications

Uccelli, P., & Phillips Galloway, E. (2020). The Language for School Literacy: Widening the lens on language and reading relations during adolescence . In P. Afflerbach, P. Enciso, E. B. Moje, & N. K. Lesaux (Ed.) , Handbook of Reading Research (Vol. 5, pp. 155-179) . Routledge.

Uccelli, P. (2019). Learning the Language for School Literacy: Research Insights and a Vision for a Cross-Linguistic Research Program . In V. Grøver, P. Uccelli, M. Rowe, & E. E. Lieven (Ed.) , Learning through Language: Towards an Educationally Informed Theory of Language Learning (pp. 95–109) . Cambridge University Press.

Featured Publications

Snow, C. E., & Uccelli, P. (2009). The challenge of academic language . In D. R. Olson & N. Torrance (Ed.) , The Cambridge handbook of literacy (pp. 112-133) . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Uccelli, P., & Snow, C. (2008). A Research Agenda for Educational Linguistics . In The Handbook of Educational Linguistics (pp. 626-642) . John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Publisher's Version Abstract Summary This chapter contains section titled: The Main Streams of Work in Educational Linguistics What are the Desired Educational Outcomes? What do Teachers Need to Know about Language? How do We Foster the Desired Linguistic Outcomes for Students and Teachers? Conclusion

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

The Importance of English: 11 Reasons to Learn the Language

What makes English an important language , not just a common one?

Is it really worth putting all that time, effort and energy into learning English ?

English is an important language for all kinds of professional and personal goals.

Whether you are just starting out or need some motivation to keep going, understanding the importance of the language will help you reach fluency and change your life .

1. English Is the Most Spoken Language in the World

2. english will teach you about world history, 3. english opens up new career opportunities, 4. english is the top language of the internet, 5. english tests can get you into school, 6. english makes traveling so much easier, 7. english allows you to make more friends, 8. english allows you to enjoy hollywood, 9. english lets you enjoy (and learn from) a ton of internet videos, 10. english widens your reading horizons, 11. learning english can make you smarter, and one more thing....

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

According to a report from Statistics & Data, English is the most spoken language in the world .

And if you include people who use it as a second language, an estimated 1.5 billion people worldwide speak English. Further, a total of 96 countries in the world use English .

Considering that there are over 190 countries , that means over half of the countries you will visit likely use English as their lingua franca —the main language that people from various groups use to communicate with each other.

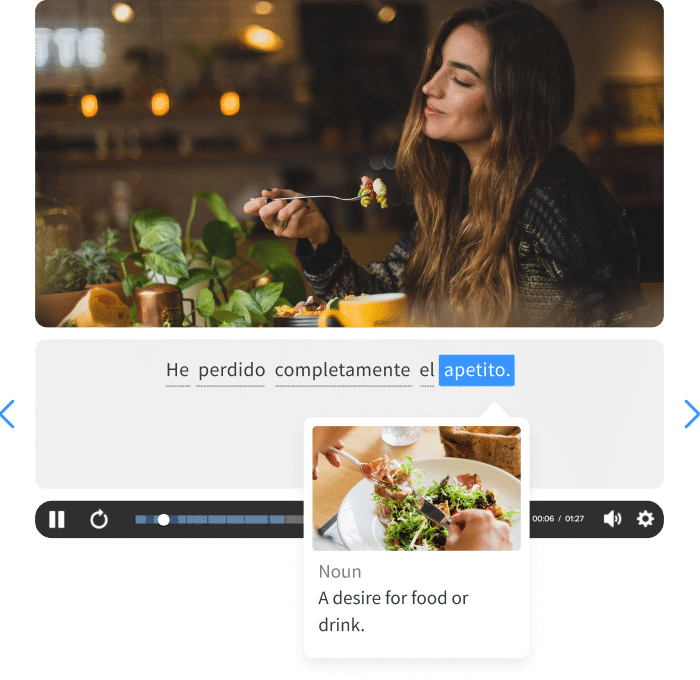

- Thousands of learner friendly videos (especially beginners)

- Handpicked, organized, and annotated by FluentU's experts

- Integrated into courses for beginners

Throughout the centuries, the British Empire expanded and ruled over many different countries. The empire (a group of countries ruled by a single government) forced the people they ruled over to speak English.

Because the empire lasted over 300 years, many of the countries under the former British Empire (like Ireland, which had Gaelic as its original language ) speak English to this day.

When you are studying English, you will come across the different types used around the world . When you know the history of English as it is used in a certain country, the similarities and differences between, say, Australian and New Zealand English make much more sense.

Many companies need employees who can communicate with partners and clients all over the world. Very often, that means finding employees who speak English.

Are you job hunting ? Do you just want to keep your professional options open? Learning English can be an important step to achieving those goals.

The global job market has even created new positions for bilingual people (people fluent in two languages). By learning English, you could become a translator, a language teacher or an English marketing professional for a global company.

- Interactive subtitles: click any word to see detailed examples and explanations

- Slow down or loop the tricky parts

- Show or hide subtitles

- Review words with our powerful learning engine

Like in real life, English is the most-used language online, with 55 percent (or over half) of all websites using the language. That means if you can understand and read English, you can access and enjoy a lot of written resources online.

For example, you can read online news articles . You can participate in a discussion on a forum like Reddit . You can send an email to someone from halfway across the globe. The possibilities are endless!

Also, many people and businesses conduct (do) research, market themselves or communicate and develop connections on sites like LinkedIn —making internet English crucial to professional success as well.

If you learn English well enough to pass tests like the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language), you can study in English-language universities across the globe.

The TOEFL is one of the most common English proficiency tests. Others include the IELTS (International English Language Testing System) and the Cambridge exams . Some colleges or language centers even offer classes to help you practice for these tests.

Even if you are not taking a test for a specific reason, studying for an English exam can still help you improve your language skills.

Just knowing English travel phrases is great if you just want to do things like get around a hotel or ask for directions. But if you want to stay in that country for at least a few years or so, you need to expand your vocabulary.

- Learn words in the context of sentences

- Swipe left or right to see more examples from other videos

- Go beyond just a superficial understanding

For example, if you live in an apartment (a room or unit in a building where you pay rent to a landlord), you need to know some house vocabulary in case you have trouble with your bathroom and need to ask someone for help.

And if you regularly interact (come into contact with) native English speakers, you need to know what the daily phrases they use mean.

Because English is the most widely used language online and offline, you are likely to meet English speakers when you are traveling or using chat apps like WhatsApp .

When you know their language, it is easier to share common interests like your favorite food , music and much more.

And hey, you may even want to surprise your new buddy (friend) with some of the weirdest English words you know—or at least ask them about the best way to use those words.

Understanding English means you can enjoy modern Hollywood blockbusters (very popular/successful movies) as well as classic films from different generations —and talk about them with other film-loving, English-speaking friends .

Not sure where to watch movies in English? Check out streaming services like Netflix or Amazon Prime Video as well as free services like Crackle and Tubi TV .

- FluentU builds you up, so you can build sentences on your own

- Start with multiple-choice questions and advance through sentence building to producing your own output

- Go from understanding to speaking in a natural progression.

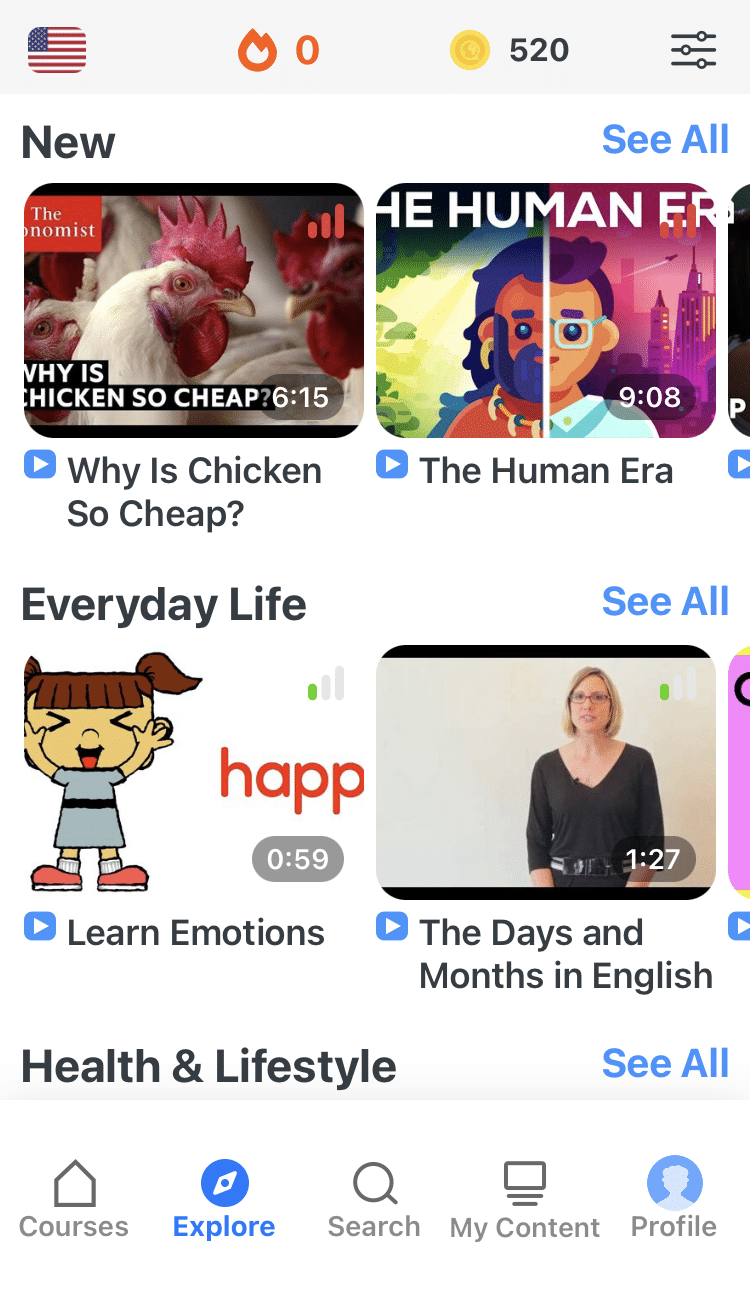

If you do not have time for a movie marathon (an event where you watch two or more movies consecutively), websites like YouTube and Vimeo can also give you engaging English videos that discuss all kinds of topics.

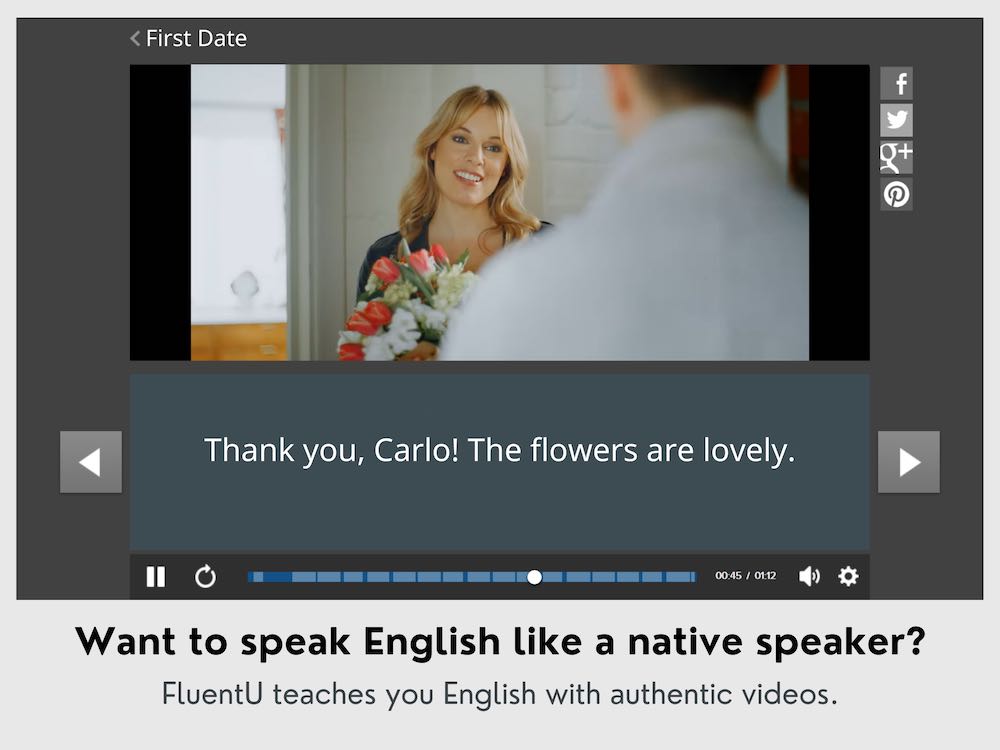

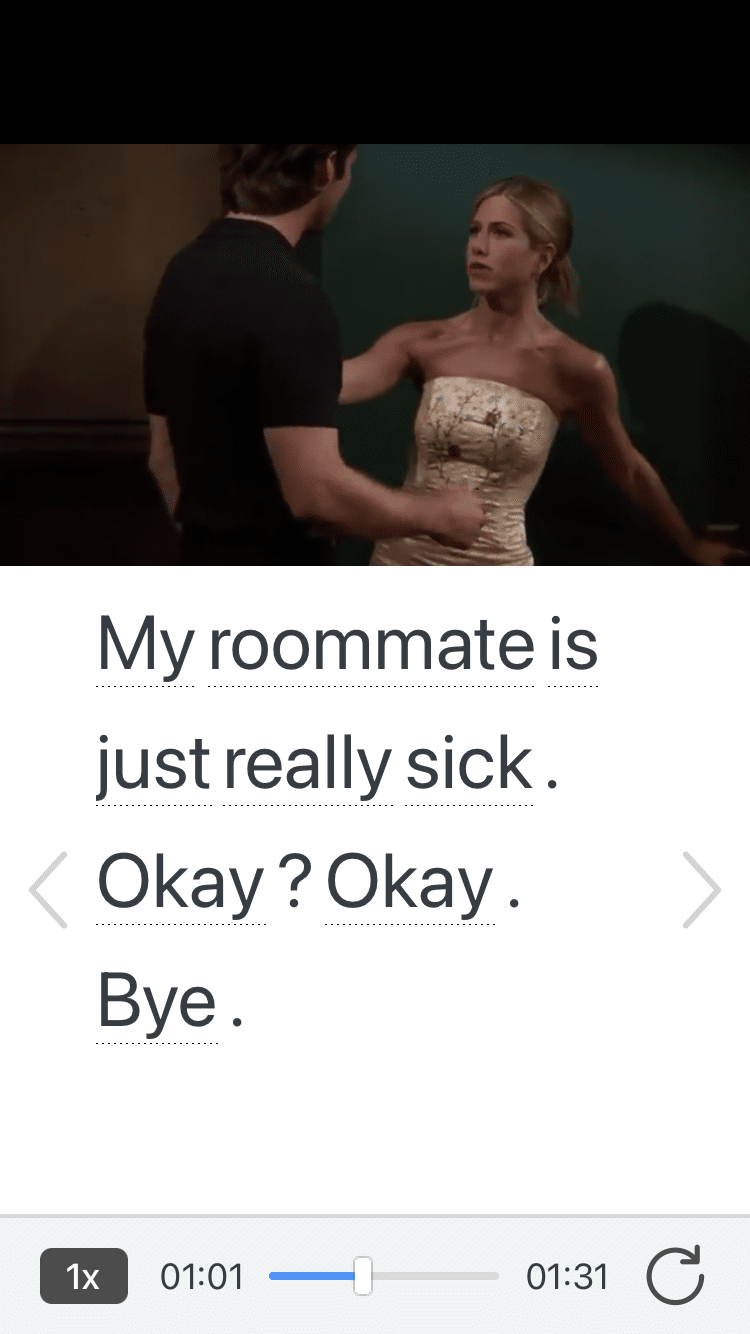

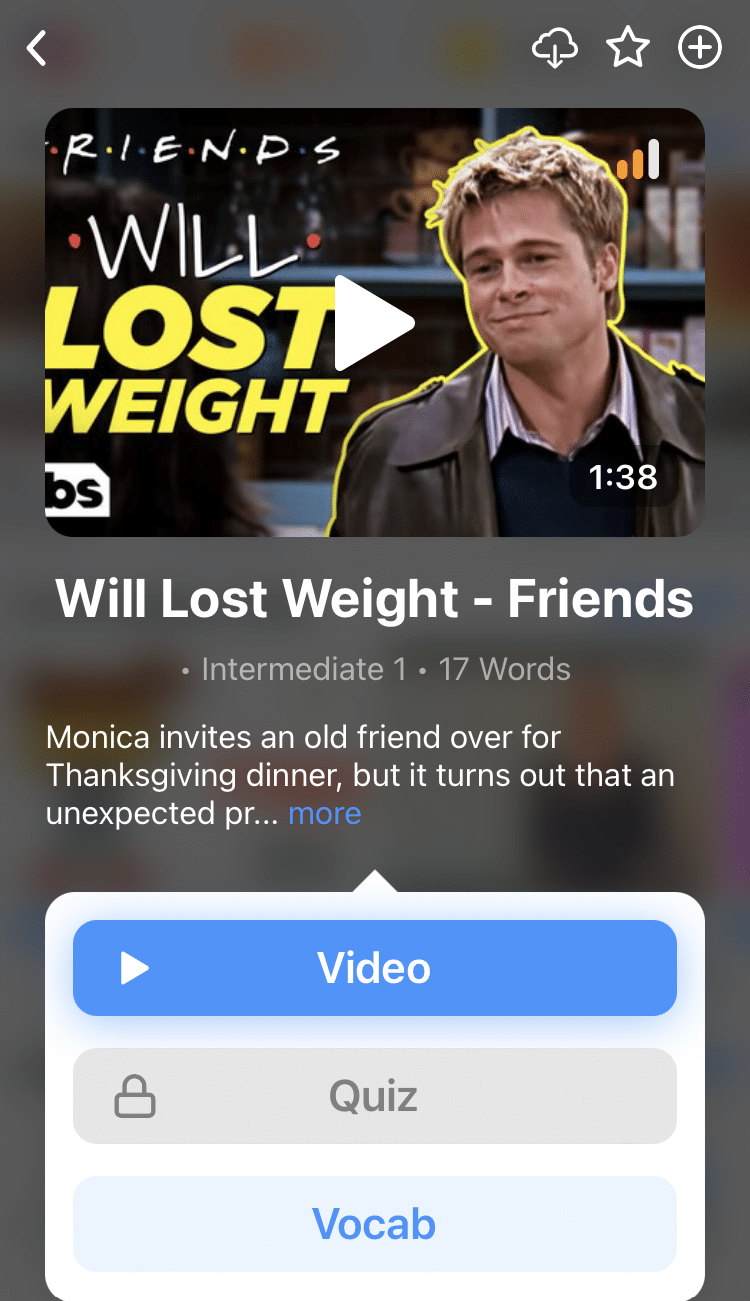

FluentU takes authentic videos—like music videos, movie trailers, news and inspiring talks—and turns them into personalized language learning lessons.

You can try FluentU for free for 2 weeks. Check out the website or download the iOS app or Android app.

P.S. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Try FluentU for FREE!

Want to put more books on your bookshelf? When you know English, you can read popular books written in English like “Harry Potter,” “Twilight,” “The Hunger Games” and more.

If you want to read books in English for free, here are some options:

- Check out a local library. Even if you don’t live in an English-speaking region, your library likely has an English- or foreign-language section.

- Use e-book services like Kindle or Nook . These usually have many free downloads. Browse their huge selections to see if any free English books interest you.

- Visit sites that have books in the public domain. When you say that a book is in the public domain , it means the book’s copyright has expired. In other words, you can legally download the book for free. One good site for books like these is Project Gutenberg —if you are taking an English literature class, this resource will come in handy!

Research shows that learning a new language changes your brain structure (in a good way). It impacts the parts of your brain responsible for memory, conscious thought and more.

Put simply, learning a new language can make your brain stronger and more versatile (flexible or able to do more things).

- Images, examples, video examples, and tips

- Covering all the tricky edge cases, eg.: phrases, idioms, collocations, and separable verbs

- No reliance on volunteers or open source dictionaries

- 100,000+ hours spent by FluentU's team to create and maintain

Research also shows that bilingualism can keep the brain strong and healthy into old age and help with memory, concentration and other skills.

Well, what are you waiting for? Now that you know the importance of the English language, you can start learning . The sooner you do so, the sooner you can enjoy all of these benefits!

If you like learning English through movies and online media, you should also check out FluentU. FluentU lets you learn English from popular talk shows, catchy music videos and funny commercials , as you can see here:

If you want to watch it, the FluentU app has probably got it.

The FluentU app and website makes it really easy to watch English videos. There are captions that are interactive. That means you can tap on any word to see an image, definition, and useful examples.

FluentU lets you learn engaging content with world famous celebrities.

For example, when you tap on the word "searching," you see this:

FluentU lets you tap to look up any word.

Learn all the vocabulary in any video with quizzes. Swipe left or right to see more examples for the word you’re learning.

FluentU helps you learn fast with useful questions and multiple examples. Learn more.

The best part? FluentU remembers the vocabulary that you’re learning. It gives you extra practice with difficult words—and reminds you when it’s time to review what you’ve learned. You have a truly personalized experience.

Start using the FluentU website on your computer or tablet or, better yet, download the FluentU app from the iTunes or Google Play store. Click here to take advantage of our current sale! (Expires at the end of this month.)

Enter your e-mail address to get your free PDF!

We hate SPAM and promise to keep your email address safe

Why English is Important in Education

Why english is important in education.

Why should I learn English? Indeed English has been described as “the language of opportunity” Learning English has become almost must for every student living in any part of the universe and the number of learners Increase rapidly every year.”Why English is Important in Education.” We will look here at ten great reasons why learning English as a second language is important.

1. English is one of the most widely spoken Languages throughout the world. People from different countries communicate with each other using English.60 country have English as their official language and adopted as a second language in great many more countries. In total around 1.5 billion people speak English Worldwide.

2. Knowing well English will open more opportunities for you and make you bilingual and more employable in every country in the world.

3. English is the language of science and the language of business. If you want to excel in Science and in your business, you have to know English well.

4. English has a simple alphabet and compared to some languages, it can be learned fairly quickly.

5. Having The certificate of International English Language Testing System (IELTS) will give you the opportunity to access in any famous university throughout the world.

6. Knowing English will make you aware of worldwide and increase the standard of living. Because English is the language of the media industry and you will excel through books, films, TV shows if you know English.

7. Knowing English also make you to use technology in a proper way, perform your tasks easily and improve your life.

8. Learn English and receive more salary. In Every country English speakers will be given priority to be employed in a job and will receive more salary than non-native speakers.

9. English is the language of the internet. Many websites are in English, you will be able to have self study, by getting help from the internet and accesses in your knowledge. Also, you can participate in forums and discussion on the internet and make more friends.

10. Learn English and feel free to attend any international conference or events. Major sporting events and international conferences are held in English and competitors or commentators will speak in English, so learning English will be an enormous benefit to you.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

Related posts

Best discussion titles in english, anchoring script for the teacher’s day for school function, new american streamline connections glossary part a.

I ‘m Very agree with you but what are the best medhods to achieve his ambitions .My First official language is french and like enghish for these reasons .l’m living in Ivory cost (cte d’ivoire) but I’d like to go to an enghish country to improve my English in order to improve my life. Thanks so much

Dear ZIAO, the best way to enhance your English is to go to an English country and communicate with native speakers.

Wonderful points!! I completely agree with all those. Thank you for the post! keep updating with more such information.

you don’t have conclusion

Indeed, this article doesn’t need any conclusion.

I needed a speech not this . Well but helpful.

You can get a clue from this Article and add it in your speech.

very short but to the point and comprehensive. Thank you so much.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Open access

- Published: 26 January 2016

The importance of English in primary school education in China: perceptions of students

- Grace Yue Qi 1

Multilingual Education volume 6 , Article number: 1 ( 2016 ) Cite this article

89k Accesses

30 Citations

23 Altmetric

Metrics details

English has become a compulsory subject from Primary Three in China since 2003 and is gradually being introduced even earlier into the curriculum in many schools. This highlights the official importance of English in both primary school education and society. However, although a compulsory subject, there are fewer English lessons than for Chinese and mathematics, the other core subjects. This raises questions about the real status of English in primary school education and whether it is really perceived as important. This paper firstly examines China’s current primary school English language education policy and discusses the implications for the primary school curriculum. Adopting a qualitative research design, which included six focus group interviews with students, the study investigated the attitudes of students toward the learning of English in the primary schools. The study was conducted in three different government schools with varied socio-economic status. Findings show the positive attitudes of children toward English education and their support for the early introduction of English; however, some feel that English is not as important as Chinese and mathematics. After reporting and discussing the different perspectives of the students, this paper concludes by considering the implications for English education in primary schools in China and other Asian countries.

Introduction

As a multilingual country, China represents a complex linguistic society, but one in which English is promoted as the key to modernisation by policy makers. At different periods, English has been highly regarded in military, political and economic terms for nation-building; however, the language has also been seen as a threat to national integrity (Adamson 2002 ). Therefore, the history of English language education in China has been controversial since it was first introduced into the Chinese education system in 1902 (Gu 1996 ). In recent years, although English has been the priority foreign language in education as well as in society, the real status of English is under question. First, in schools, in terms of contact hours, it has fewer than the other core subjects. Second, English has no legal status in China (Gil and Adamson 2011 ). Previous studies on English education in Chinese schools have key emphasis on the language education reforms (Hu 2012 ), language policy and planning (Kaplan et al. 2011 ; Li M. 2011 ), teaching pedagogy (Hu 2002 ), and teacher beliefs (Zheng 2015 ). Kaplan et al. ( 2011 ) reinforces the importance of communities beyond the policy making, underlining the necessary research on the ‘bottom-up’ responses to English language education policies, however little research has been conducted. Chen (2011) investigates the attitudes of parents toward English education in Taiwanese primary schools and concludes that parents lobby the government to introduce English earlier and strongly advocate for consistency in English language policies. Since Taiwan shares similar socio-cultural concerns in English education in schools, Chen’s study provides a good reference and example for further studies. However, her study needs expanding research subjects, namely, other key stakeholders. Students, as English language learners at school, are one of the most crucial stakeholder groups highly involving in the language education process. Hu (2003) examines the endeavours of students to learn English as a foreign language on the effect of socio-economic backgrounds. The regional differences have been identified on English proficiency, classroom behaviours, and language learning and use strategies. However, Hu’s study focuses on the context of post-secondary students from China studying in Singapore. For these students, although their backgrounds vary, compared to those rural (migrant) students, they have received much support and resources to continue studying overseas. More importantly, reasons behind the trend of early exposure to English are yet to be investigated. The present study is an attempt to explore the importance of English for students in primary schools in China and how students from different Socio-Economic Status (SES) backgrounds differ in their attitudes toward English. It is crucial to understand young learners’ beliefs and real needs in order to benefit the teaching and learning experiences in the current primary school context. In this paper, it aims to answer three questions:

Do students believe that English is important in primary school education?

Why do they think the way they do?

What are the potential implications?

The National English Curriculum

As China’s economy was boosted due to open foreign policies and the use of English, the policy makers of the Ministry of Education (MOE) decided to include English as the first compulsory subject in the secondary school curriculum and tertiary level of study. In 2001, the MOE issued a document entitled ‘Guidelines for Promoting English Language Instruction in Primary Schools’ (MOE 2001 ) emphasising a new approach for using English for effective interpersonal communication. This document supported the early introduction of English language teaching in China (Gao 2009 ). Then, after two years of consultation and trials, a new ‘student-centred’ English language curriculum was announced for all primary and secondary schools (MOE 2003 ). Most recently, the latest version, 2011 English Language Curriculum Standard (MOE 2011 ) has been introduced, maintaining the main concept and design of the previous versions.

However, these updates have challenged all of the key stakeholders in the education process, especially learners in primary schools. Thus, students’ concerns over learning English, possibly influenced by their parents are worthy of study. This will facilitate an understanding of what they think of English and why they think the way they do.

The English subject in primary schools

Although English has been officially introduced as a compulsory subject in primary schools, the teaching hours in the curriculum are not comparable to Chinese and mathematics, as will be illustrated below. According to the National Curriculum, English, as one of the three core subjects, starts from Primary Three; however, local education departments and individual schools have flexibility to decide when to include English lessons. Many schools in metropolitan areas introduce English earlier, from Primary One, whilst for those in remote and rural areas, the introduction of English may have to be delayed due to inadequate teaching resources.

Generally speaking, where English starts from Primary Three, based on the National Curriculum in the version of 2011, the weekly lessons for three core subjects in primary schools are required as shown in Table 1 (table designed according to MOE 2011 ). From Primary Three to Six, students are offered three English lessons per week with 40 min per lesson. However, the weekly contact hours for Chinese and mathematics are greater over six years of study. Compared to the minor subjects, such as PE, science and music, English has a similar number of lessons (MOE 2001 ). English, based on hours taught, could therefore be regarded as a minor subject. However, the status of English is very contradictory, as in exams, Chinese, mathematics and English are always considered as three core subjects, particularly because they are worth the same marks.

Furthermore, there is a limited selection of English textbooks for local education departments and individual schools. All the available textbooks are designed in accordance with the National Curriculum. This raises an issue for those introducing English earlier than the curriculum requires, as there are no official textbooks to choose from for Primary One and Primary Two. As a result, the structure of English classes in both years varies. Some schools use other commercial materials. Others, for instance, foreign language(s) primary schools sponsored by local governments or community, are more flexible with the teaching content and aim to offer a more interactive approach in a form of task-based language instruction that is derived the spirit of Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) (Littlewood 2007 ). The CLT approach has been adopted in the education developed areas in China recent years incorporating two perspectives of teaching on: 1) the communicative functions and formal properties of English to engage students in using the language in problem solving activities, namely, task-based language teaching (Hu 2005 ; Littlewood 2004 ); and 2) natural interaction in English according to the content-based English instruction (Hu 2003 ). Despite the National Curriculum has promoted the task-based English teaching since 2001, both approaches are commonly used in classroom pedagogy and of which one is actually used depending upon the materials, teachers and subject organisation. In short, schools are the decision-makers in terms of what to teach, and how to teach, in Primary One and Primary Two, but the syllabus is fixed from Primary Three.

Urban and rural differences: families, schools and children

The ‘one child’ policy, introduced in 1978 and officially applied in 1979, has changed the family and social structure in China (Chai 2012 ). The structure of the family has been transformed into a ‘4-2-1’ model; four grandparents, two parents, and one child in each family (Shwalb et al. 2003 ). Within this structure, children in urban areas have become the centre of families and are carefully nurtured by their parents and other family members (Fong 2007 ). At the same time, since the ‘open door’ policy was implemented in China, social changes and economic reforms have substantially increased individual and family incomes in urban and city areas (Adams and Hannum 2007 ; Brown and Park 2002 ; Brown 2003 ; Hannum 2003 ; Hannum et al. 2009 ; Zhang Y. 2011 ). Therefore, this ‘open door’ policy has ensured urban parents can invest more in education for their children.

In contrast, there is a different story in rural areas of China. As people in rural areas still largely rely on agriculture, labour is the priority. Prior to the introduction of the ‘one child’ policy, most rural families believed that boys are the future for family living allowances and development, as boys are necessary for labour in agriculture. At the same time, a specific ‘father-son’ relationship following Confucian tradition, characterised by filial piety, is considered as the most important cultural heritage and value in rural families (Dong and Simon 2010 ). After the national implementation of the ‘one child’ policy, it is not surprising that most of the Chinese residents in rural settings have faced challenges, as a consequence of inadequate labour in rural communities. Children in rural family settings are still unable to access the same educational resources as those born in urban areas. In order to increase their family income and improve living conditions, millions of couples from rural areas seek work opportunities in cities, especially in the developed south-eastern regions. These people are migrant rural workers ( 农民工 nong min gong) who undertake labour and low-status jobs in cities to strive for a better life for their children and themselves. However, these rural workers have to register as rural residents working in cities with fundamentally different welfare systems, in employment, housing and access to schools. Therefore, the majority of the rural migrant workers leave their children in their hometowns to be cared for by the grandparents’ generation or parents’ generation (relatives and friends) (Zhou and Qing 2007 ). Some children may be fortunate enough to stay with their parents in cities; however, they have to look after themselves or be cared for by their older siblings. These children are called ‘left-behind’ children (Li 2002 ; Lv 2007 ).

Methodology

This study conducted six focus group interviews with students in three different government primary schools in Nanjing, Jiangsu Province. Each school had students from different socio-economic backgrounds. Expressions of interest to participate in the study were displayed on the school noticeboards. Only those who contacted the researcher indicating a willingness to participate were considered for the focus group interviews. Two groups were formed from each school, with each group containing four to five students aged 9 to 12, studying from Primary Three to Six. Their participation was approved by their parents/guardians. The three different government primary schools were chosen based on the socio-economic profile of their students. School One is a prestigious and well-resourced government school, which represents the medium SES status of school in Nanjing. This school locates in a new area of the Nanjing West and the majority of students who live nearby and their parents are mostly middle class. School Two is a low SES status school, of which the majority of students have parents who are rural migrant workers. Students (approximately 95% of a total number) match the categorisation of ‘left-behind’ as mentioned earlier. School Two is also one of the only four government schools where accepts migrant children to study. This school, thus, represents a low SES school within the developed city. School Three is a unique government school providing performing arts and academic curriculum. This school only admits students who are talented in music, dancing or singing and also reside in Nanjing. The majority of students come from relatively high SES status families as their parents are generally well-educated and willing to invest extra time and effort for children in performing arts and academic study. It is important that the three schools represent three different styles and levels of SESs in Nanjing and China to provide an insightful understanding of students and generate reliable and generalised results for analysis. The interviews were semi-structured and designed to seek the attitudes and perceptions of students on the importance of English. Putonghua was the language utilised in the interviews. A thematic approach elicited themes identified from the interview data. The thematic analysis was based on the original data in Chinese. The procedures shown in Table 2 were adapted from Braun and Clarke ( 2006 ).

Four themes were identified, namely:

Early introduction of English

Importance of English and reasons for English education

Parental demand and expectations

Examinations and admission

As the students were under 18, their names and details were protected and coded in the form capital letter S, underline and number. Table 3 shows the student reference number, age, interview group, year of primary school and which school they were studying at.

Theme 1: Early introduction of English

The students from School One, the prestigious school, reported that they had early exposure to English. Table 4 shows the details of their early exposure. Only four students first started to learn English in school with the remaining six students being exposed to English much earlier from kindergarten. One was also enrolled in private tutoring.

Although the students stressed that they were under pressure to learn English, they still preferred to start English early as English was beneficial to them (S1_S1, S1_S3, S1_S7 and S1_S10) and would be useful for their future (S1_S2). In addition, as English was still regarded as a minor subject in Primary One and Two, the students felt there was less pressure, despite the need for assessments and homework.

Five students interviewed reported that they had first encountered English when they were in their first year of government funded kindergarten. However, as their parents were rural migrant workers, the students might have had to move to different schools in different places dependent upon their parents’ work commitments. Table 5 indicates the details about the first exposure of students to English, including the time and formal setting. The other four students started English at various points in their primary school education.

Their experience of early learning English varied: some felt it was very enjoyable while others regarded Primary One and Two English as “task completion” rather than a learning process.

School Three

School Three only offers English from Primary Three, following the National Curriculum. However, this was considered as a ‘late’ start in Nanjing and the students of School Three were typically enrolled in extra curricula English classes to make up for the ‘later’ learning of English at school. Table 6 demonstrates the details of their first exposure to English. With the exception of two students, the remaining eight students started English very early and much earlier than it was offered at school. Their first exposure to English happened in either kindergarten or private classes when they started in Primary One. They reported that they had benefited from learning English earlier as they could be more confident when the school started to offer English lessons from Primary Three.

Theme 2: Importance of English and reasons for English education

In terms of reasons for English education, the students provided individual explanations, which also showed their perceptions of the importance of English. Their comments included:

S1_S1: learning English is for communication when travelling to other countries after I am grown-up. At the same time, others also ought to understand English. S1_S2: I have nothing too much [to say]. I think I feel proud if I can learn the English language well. (S1_S2 further explained that ‘pride’ related to gaining an ‘advantage’ over peers.) S1_S3: I think English is a world/international language. If [I] could learn it well, [I] would not have a problem to travel around most countries in the world. S1_S4: [It is] because English will be very helpful if [I] study abroad in the future. S1_S5: English is a useful language, if [I] am going to study overseas. S1_S6: With regard to English, if some foreigners come to China and [I] want to make friends with them, it is important to have ability in speaking English. Otherwise, [I] cannot communicate with them. S1_S7: It’s rare that foreigners can speak Chinese (when you communicate with them). Since there’s a cost to hire an interpreter, having an ability to speak English is important…to be able to teach foreigners Chinese, learning English is necessary. S1_S8: This is because we can approach foreigners and communicate with them if we learn English well. S1_S9: I also think English is considerably important. This is because, for example in the recent Youth Olympic Games (which took place in August 2014 in Nanjing), as some foreigners [will] come to Nanjing, we can [take this opportunity to] communicate with them. S1_S10: [It is] very important. English is very useful when [I am] overseas in the future.

The same discussion was held in the focus groups of School Two; however, the group two students compared English with the other subjects. They ranked English among all the subjects in the school but none of them put English first. As shown in Table 7 , English was considered less important than Chinese. However, from the perspectives of all the students in School Two, it remains a major subject in primary school education.

The students provided their reasons why they believed English was important.

S2_S1: My parents and I believe that English is very important for my future. If travelling overseas later on, [I] could communicate with foreigners in English. International communication is crucial, thus my parents encourage me to learn English well. S2_S2: My parents believe that English is very important. [For me], [I think] Chinese, Mathematics and English are equally important. S2_S3: I feel that English is quite important. However, English teachers sometimes are very strict and harsh. I understand that English teachers are trying to push us a bit more to study harder. But, I have to say that our homework is way too much – especially we have to repeatedly copy the same words at least ten times to prepare for upcoming exams (written exams). S2_S4: I think English is important. If [I] don’t know English, I will neither be able to graduate from the primary school nor be able to enter a better secondary school. S2_S5: It is, [it should be] just interesting. S2_S6: I think that I should say after I grow up, English is useful if travelling overseas. S2_S7: Many people have started learning English nowadays. It is beneficial for finding a job, admission to better schools and qualifications. S2_S8: I want to just include all of what the other people have just mentioned. S2_S9: I think it is fun and interesting.

The students of School Three did not mention individually how important English was for them. However, they reported that their learning of English was not based on their personal interests, but because their parents wanted them to learn it. The main purpose for them to learn English well was primarily because of examinations, parental expectations and admission to good secondary schools. Examples were provided by two students S3_S6 and S3_S7.

S3_S6: I am in Primary Three, but my English is still at the level of beginner. As my parents focus on my English (study) very much, I have much pressure in English. I did not know English until my mom taught me every day. At the school, although my English score is very good in exams, I still need to continue to work hard in learning English. S3_S7: …I like English. My parents also pay much attention to my English learning. I, at least, dictate one unit of words (from textbooks) every day.

Theme 3: Parental demand and expectations

Several students of School One reported that they had attended private English tutoring since kindergarten. They repeatedly mentioned that their parents had enrolled them in those programs and that they expected them to achieve better results in school English exams and rank top in their class. Four of them said they were stressed from studying English after school.

S1_S1: I have to complete homework before relaxing. S1_S2: I also have to finish all my homework, including those from school and extra classes, prior to relaxing. S1_S3: I feel irritated [when I see] many books piled up on the desk. I hope to have a 20-minute break for every one hour of homework. S1_S4: I have not been allowed to watch TV since Primary One. I have to complete all my homework prior to relaxing.

These comments highlighted the intensity of parental demand for English education for these primary school children, and also how much pressure these students experienced.

It was evident that the parents of nine students in School Two had been heavily involved in their English education. All the students interviewed came from rural migrant families, which represented 90 % of students in School Two. According to the students, the parental expectations in their English academic performance were very high. Table 8 summarises what their parents expected them to achieve in English tests. The majority were required to obtain at least 90 % in each English test. For the students in senior years, in addition to expected scores, they also had to ensure that they ranked in the top three of their class in every test. Their parents thus expected continued high academic performance from them.

A comment agreed to by all nine students was, “if I cannot meet the target, I would have to face punishment” (S2_S6).

The students indicated that their parents expected them to reach a specific standard at school, such as being in the top three in each exam in the class (S3_S2) and above average in the class (S3_S4 and S3_S5). Some students were afraid of exams. For instance,

S3_S2: I [often] feel nervous in exams.

In order to meet their parental expectations, the students were enrolled in extra curricula English classes mainly once a week. Only student (S3_S7) dropped out of the class, because her parents were finally aware of the pressure she was under.

S3_S7: … too many students in one class…and also too often a change of teachers…it was less fun compared to the school. My parents agreed with my wishes of not continuing to study there. S3_S8: at the beginning, I felt it (English) was fun, which was because [we can] play games – very interesting. I have always been enrolled in [the extra curricula class]. [I] have been studying in several [English] classes. S3_S9: I started to learn English outside the school from the second semester of Primary Three…I wanted to study because I already get along with classmates and teachers over there; however, I am also OK if I was not enrolled. S3_S10: My parents believe the level of English taught in the school is too easy, hence they want to push my proficiency of English to a higher standard.

Theme 4: Examination and admission

For many families, studying in quality secondary schools means more opportunities for entry to better universities. Thus, the pressure of English learning is also directly related to the Gaokao (the Tertiary Entrance Examinations). In the Gaokao , English is one of the three core subjects to be tested and it is worth the same weight as Chinese and mathematics. However, a debate regarding decreasing the worth of marks in the English test has been ongoing. This debate has attracted much attention in the community, although the potential reforms have yet to be publicly announced. The students interviewed mentioned the importance of English in relation to the examination system including the Gaokao .

The students from School One discussed examinations and admission to good secondary schools and re-emphasised the parental demand in this process. They reported that their parents expected them to enter one of the top secondary schools in Nanjing, Nanjing Foreign Languages School (NFLS). They commented as follows:

S1_S1: My parents like comparing me with other children…however, I sourced this school (NFLS) online when I was in Primary One…as this school requires a high level of English proficiency, it is likely to have more opportunities for overseas study. S1_S2: My mom asks me to go to [NFLS]…my mom told me that there was less homework in that school but there were more activities. My mom holds 98 % hope for me to get into NFLS. S1_S6 and S1_S8: Simply [NFLS] a good school where high quality of English education is provided that can help find a good job. S1_S7: The annual rate of junior high graduates from NFLS to high quality senior high is high; being able to get into a quality senior high means an opportunity for a high ranked university that also relates to jobs and my future life. S1_S9: My mom told me studying in NFLS would offer more possibility to continue studies overseas. S1_S10: My mom said the entrance tests for NFLS were in English, so getting to this school can improve my English academic performance.

Not surprisingly, eight students had heard about the possible reforms regarding English in the Gaokao . Their comments varied as follows:

S1_S1: I feel depressed. I feel I have learnt [English] in vain (if English in the Gaokao reformed). S1_S2: I think the English reform relates more to students who are going to study overseas. However, if staying in China, English is not supposed to be tested. S1_S3: I’ve heard about this news. I think it is most likely that English becomes a minor and does not require a high level of proficiency, which means that examinations should not be too difficult in the future. S1_S4: I feel surprised. S1_S5: I feel a bit happy. However, in my opinion learning English is not for exams, but to benefit ourselves. S1_S6: If it (English) is not assessed [in the Gaokao ], it cannot, eh, we cannot know how we have learnt. S1_S7: If Gaokao does not test English, our level of English proficiency cannot be measured and that increases uncertainty [of our English communication skills] when travelling overseas. In addition, there’s no doubt that English test is essential and part of the requirement of admissions to secondary schools and universities overseas, as it (English) is their native language. S1_S10: I think English test is necessary, because English is a native language of overseas countries. However, if it is not tested, the equal status of Chinese, mathematics and English will no longer exist. [In other words], English will not be such an important subject any more.

Based on the comments from the students, it was evident that they recognised the importance of examination and of admission to quality secondary schools and universities, and that English was essential for them to achieve these goals and meet their parents’ expectations.

The School Two students reported that English was essential for ‘key’ secondary school entrance examinations. They did mention NFLS; however, only one or two of them were willing to sit the entry test. There were two main reasons. First, the students were afraid of the admission standard required for NFLS (S2_S8 and S2_S9): as well as having a separate test for English, other subjects are also tested in English. Second, they wondered if their parents could provide financial support for them to study abroad (S2_S7) (as many NFLS graduates would go overseas) or whether they have considered this as an option (S2_S5). Three students had also started to think about the Gaokao .

S2_S1: I will reduce my focus on learning English in school if English is not included in the Gaokao . S2_S8 and S2_S9: Removing a subject means less pressure from overall schooling, so it is good news if English will be removed from the Gaokao .

This reflects the dilemma surrounding the attitudes of students towards English education. On the one hand, they understand the usefulness of English and are in favour of English. On the other hand, this results in great pressure for the students, as English is a core subject and tested in each exam throughout 12 years of schooling.

The students of School Three expressed their ambition to be admitted to NFLS. They indicated that their extra curricula English classes were helping them prepare for the entrance exams of NFLS. All of them knew this school provided a high quality of English education as well as a conducive learning environment. Two of them noted that their parents wanted them to enter NFLS and the parents of one student considered overseas study but not necessarily through NFLS. However, one student, S3_S6 was an exception as his parents wanted him to follow the track of ‘performing arts’ not ‘academic’ study. This is because his parents wanted to keep options open by focusing equally on both routes.

S3_S6: My parents and grandfather prepare me for the national college of arts in stage performance or dancing major…they have never mentioned NFLS. For the two students who planned to enter NFLS, their attitudes varied. S3_S7: My parents want me to get into NFLS is to study overseas later. S3_S9: I hope to study abroad but they (parents) just want me to study at NFLS without considering the option of overseas study afterwards. One student reported that her parents suggested overseas study without emphasising NFLS. S3_S8: I am not keen to study abroad (but her parents do suggest this)…I think the consequences of overseas study are extreme, to be either very successful, or failed completely…I don’t really care which school is chosen for me – I will just follow whatever they decide.

More importantly, these students had some ideas about the Gaokao ; they said their parents had already started to prepare them for it. They even followed the recent reform news with regard to English in the Gaokao .

S3_S1: I think English is still very important, as Chinese is not useful if [I am] going abroad in the future…to communicate with foreigners, the use of English is a must-have. S3_S6: Regardless of its reforms, I want to, and also must learn it (English). S3_S7: I will use my own money (gift money received from family and relatives in Chinese New Year) to enrol myself in English classes, if my parents do not approve this decision.

The students considered English as important for examinations, but to a greater extent, for their future development.

The myth of ‘the earlier the better’ in English education

The National Curriculum (MOE 2003 , 2011 ) requires the introduction of English at Primary Three. There is flexibility for school principals and local education departments for the ‘earlier’ introduction of English. In fact, many developed and wealthy regions and cities commonly introduce English from Primary One and Two. For instance, the sampling site, Nanjing, has many primary schools doing this. Two of the three participating schools, School One and School Two, also introduced English from Primary One; only School Three followed the Curriculum by not introducing English until Primary Three. Based on the results of the study, it was evident that the majority of students (19 out of 29, 65.5 %) encountered English earlier than the official introduction time. Among them, six were from School One and they had started from age three to four in kindergartens. Five students from School Two encountered English from when they were three years old in kindergarten, and all of the students from School Three started either from kindergarten or Primary One, much earlier than the official introduction in Primary Three. This result was not surprising as there has been a trend to introduce English earlier and earlier into the school curriculum across Asia (Kirkpatrick 2011 ). Although this belief is popular, it is still controversial as to whether and how the age factor affects second language acquisition (SLA) (Cenoz 2009 ). According to Cenoz and Lecumberri ( 1999 ), the early introduction of a second language may have advantages on ultimate achievement but not on the rate of acquisition. This means that the young learners may achieve certain linguistic benefits, such as pronunciation, but whether the early introduction maintains its advantages for the learners over a longer learning period is debatable. Also, school environments are not considered as natural learning settings (Cenoz 2009 ). Furthermore, in terms of the results analysed, the SES difference is less likely to affect the common belief in ‘the earlier the better’ among the students and their families.

English is not 100 % important to every child

From the ‘open door’ policy to the successful bid for the 2008 Olympic Games and membership of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001 (Zhang and Adamson 2007 ), China has been ready to “introduce the world to China and to introduce China to the world” ((Wen 2012 ), 84). English is clearly important for Chinese society. As discussed earlier, due to the power of English in developing the economy, in science and technology, the primary aim of English education for the Chinese Government was for nation building. However, questions have yet to be answered: whether English is a necessity for all children and whether children think that English is important for them. The students’ attitudes toward English were various, but were largely positive and possibly influenced by their parents and the Socio-Economic Status (SES) of their families. As the two well-resourced primary schools, the students of School One and School Three highlighted the importance of English, though they also related this to the examination system. Interestingly, the School Two students whose parents were mainly rural migrant workers in Nanjing, ranked the useful subjects in schooling with the vast majority of them prioritising Chinese. English, on the other hand, was not even ranked in the top three. It is evident that the SES difference impacts on the attitudes of students and their parents. This is because of the disparities between urban and rural families. In comparison with School One and Three, most parents in School Two had been working hard to maintain education investment in their children; however, English may become somehow extras from the main purpose of education. It is certainly important, but, with conditions along with learning the language. As some students of School Two reported, they believed English was important overall “if travelling overseas” (S2_S6 and S2_S1). However, in reality, due to limited finance and resources, it is potentially impossible for these students to travel overseas. Additionally, some students could easily stop their learning of English if it is no longer included in the Gaokao (S2_S1, S2_S8 and S2_S9). This is very different from those in School One and Three where they believed English was necessary to learn despite policy changes in the curriculum and Gaokao . It implies that the actual needs of students and contextual situations have not been properly assessed by policy makers before introducing the English language policy in primary schools. This results in the difficult or impossible policy implementation in schools across the whole nation. The young learners are told to have to learn English, which unfortunately no need of using this language becomes common, particularly appearing in the low SES schools and families.

Parental demand for English is extremely high

In the tradition of Chinese education, parents play a dominant role in the process of their children’s schooling (Hu 2008 ). Although this present study did not include parent participants, the perceptions of the parents can be indirectly identified from the responses of their children. Chinese parents generally want to invest in their children’s education, not surprisingly as Confucian philosophy prioritises education in society (Wei 2011 ). Since the introduction of the ‘one-child’ policy in the 1980s, the structure of the Chinese family has been changed to a ‘4-2-1’ model (Shwalb et al. 2003 ). Under this model, the single child has become dominant and more important in a family unit, a trend particularly pronounced in urban areas (Fong 2007 ). In terms of English education, though parents may not have enough knowledge to help their children, there is no doubt that they find alternative ways to assist their children in learning. One approach is private tutoring, which is very popular across the nation. The results demonstrated that an aim of enrolling in private tutoring was to achieve better academic performance in exams. The students reported their fear and pressure associated with exams, as their parents expected very high performance from them, not only scores but also expected them to be among the top of the class. Regardless of the SES of parents, their high expectations and demand for English education for their children were the same.

Examination-driven English education relates to the admission to school and tertiary levels

In spite of the task-based teaching approach and the focus of communication in the latest National Curriculum (MOE 2011 ), the reality of classroom teaching still follows the traditional mode: teacher-centred and examination-driven. Fundamentally, it is because the examination system has never been updated and focuses only on written performance across the 12 years of school education. This has resulted in different problems: first, the students have suffered great pressure from learning English; second, this pressure has been due to the fierce competition to be admitted to quality secondary schools and universities. Overall, the students in this study were acutely aware of the importance of examinations. English education in China is still examination-driven. At the same time, students generally reported that they believed English was important for them, not just for examinations, but to a greater extent, for their personal development. The view was shared generally by students from School One and School Three, while the students in School Two did not express the same. This can refer to the SES difference as the students and their parents from School Two have to overcome more difficulties and challenges; as for majority of them, education has been the way to success and examination is the fairest solution to these students from low SES migrant rural families.

This study has elicited and discussed the attitudes and perceptions of primary school students on the importance of English in primary school education in Nanjing, China. Regardless of the socio-economic differences among the three participating schools, four key issues emerged with regard to the importance of English. To begin with, ‘the earlier the better’ approach is generally supported by students across the three schools. Second, the status of English is lower than the other two core subjects, Chinese and mathematics, mainly due to there being fewer teaching hours. However, the students still recognised that English was important for examinations. Parental demand and expectations for English education are high. According to all of the students, their parents expect them to achieve the best possible scores and rankings among peers in their English learning in primary schools. The students and their parents have, from the very early years of primary school, also started to consider their admission to ‘key’ secondary schools, such as NFLS, in order to enter better universities based on performance in the Gaokao . Many students are enrolled in private English tutoring after school, which adds on even more pressure to them. With respect to the varying socio-economic backgrounds, students’ attitudes and perceptions differ mainly in the reasons of learning English. It is very important to understand that students from low SES backgrounds have to face much more challenges on the education pathways. Their strong belief in ‘learning English primarily for examinations and admissions’ implies the “significant differences” ((Cortazzi and Jin 1996 ), 61) among urban and rural in China’s language teaching developments. In short, the students’ opinions are worthy of note and should be acknowledged by the policy makers and the Ministry of Education (MOE).