- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

The Craft of Writing a Strong Hypothesis

Table of Contents

Writing a hypothesis is one of the essential elements of a scientific research paper. It needs to be to the point, clearly communicating what your research is trying to accomplish. A blurry, drawn-out, or complexly-structured hypothesis can confuse your readers. Or worse, the editor and peer reviewers.

A captivating hypothesis is not too intricate. This blog will take you through the process so that, by the end of it, you have a better idea of how to convey your research paper's intent in just one sentence.

What is a Hypothesis?

The first step in your scientific endeavor, a hypothesis, is a strong, concise statement that forms the basis of your research. It is not the same as a thesis statement , which is a brief summary of your research paper .

The sole purpose of a hypothesis is to predict your paper's findings, data, and conclusion. It comes from a place of curiosity and intuition . When you write a hypothesis, you're essentially making an educated guess based on scientific prejudices and evidence, which is further proven or disproven through the scientific method.

The reason for undertaking research is to observe a specific phenomenon. A hypothesis, therefore, lays out what the said phenomenon is. And it does so through two variables, an independent and dependent variable.

The independent variable is the cause behind the observation, while the dependent variable is the effect of the cause. A good example of this is “mixing red and blue forms purple.” In this hypothesis, mixing red and blue is the independent variable as you're combining the two colors at your own will. The formation of purple is the dependent variable as, in this case, it is conditional to the independent variable.

Different Types of Hypotheses

Types of hypotheses

Some would stand by the notion that there are only two types of hypotheses: a Null hypothesis and an Alternative hypothesis. While that may have some truth to it, it would be better to fully distinguish the most common forms as these terms come up so often, which might leave you out of context.

Apart from Null and Alternative, there are Complex, Simple, Directional, Non-Directional, Statistical, and Associative and casual hypotheses. They don't necessarily have to be exclusive, as one hypothesis can tick many boxes, but knowing the distinctions between them will make it easier for you to construct your own.

1. Null hypothesis

A null hypothesis proposes no relationship between two variables. Denoted by H 0 , it is a negative statement like “Attending physiotherapy sessions does not affect athletes' on-field performance.” Here, the author claims physiotherapy sessions have no effect on on-field performances. Even if there is, it's only a coincidence.

2. Alternative hypothesis

Considered to be the opposite of a null hypothesis, an alternative hypothesis is donated as H1 or Ha. It explicitly states that the dependent variable affects the independent variable. A good alternative hypothesis example is “Attending physiotherapy sessions improves athletes' on-field performance.” or “Water evaporates at 100 °C. ” The alternative hypothesis further branches into directional and non-directional.

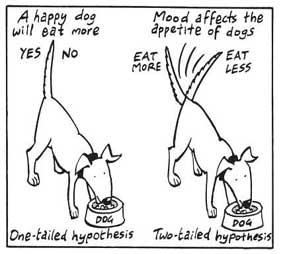

- Directional hypothesis: A hypothesis that states the result would be either positive or negative is called directional hypothesis. It accompanies H1 with either the ‘<' or ‘>' sign.

- Non-directional hypothesis: A non-directional hypothesis only claims an effect on the dependent variable. It does not clarify whether the result would be positive or negative. The sign for a non-directional hypothesis is ‘≠.'

3. Simple hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement made to reflect the relation between exactly two variables. One independent and one dependent. Consider the example, “Smoking is a prominent cause of lung cancer." The dependent variable, lung cancer, is dependent on the independent variable, smoking.

4. Complex hypothesis

In contrast to a simple hypothesis, a complex hypothesis implies the relationship between multiple independent and dependent variables. For instance, “Individuals who eat more fruits tend to have higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.” The independent variable is eating more fruits, while the dependent variables are higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.

5. Associative and casual hypothesis

Associative and casual hypotheses don't exhibit how many variables there will be. They define the relationship between the variables. In an associative hypothesis, changing any one variable, dependent or independent, affects others. In a casual hypothesis, the independent variable directly affects the dependent.

6. Empirical hypothesis

Also referred to as the working hypothesis, an empirical hypothesis claims a theory's validation via experiments and observation. This way, the statement appears justifiable and different from a wild guess.

Say, the hypothesis is “Women who take iron tablets face a lesser risk of anemia than those who take vitamin B12.” This is an example of an empirical hypothesis where the researcher the statement after assessing a group of women who take iron tablets and charting the findings.

7. Statistical hypothesis

The point of a statistical hypothesis is to test an already existing hypothesis by studying a population sample. Hypothesis like “44% of the Indian population belong in the age group of 22-27.” leverage evidence to prove or disprove a particular statement.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

Writing a hypothesis is essential as it can make or break your research for you. That includes your chances of getting published in a journal. So when you're designing one, keep an eye out for these pointers:

- A research hypothesis has to be simple yet clear to look justifiable enough.

- It has to be testable — your research would be rendered pointless if too far-fetched into reality or limited by technology.

- It has to be precise about the results —what you are trying to do and achieve through it should come out in your hypothesis.

- A research hypothesis should be self-explanatory, leaving no doubt in the reader's mind.

- If you are developing a relational hypothesis, you need to include the variables and establish an appropriate relationship among them.

- A hypothesis must keep and reflect the scope for further investigations and experiments.

Separating a Hypothesis from a Prediction

Outside of academia, hypothesis and prediction are often used interchangeably. In research writing, this is not only confusing but also incorrect. And although a hypothesis and prediction are guesses at their core, there are many differences between them.

A hypothesis is an educated guess or even a testable prediction validated through research. It aims to analyze the gathered evidence and facts to define a relationship between variables and put forth a logical explanation behind the nature of events.

Predictions are assumptions or expected outcomes made without any backing evidence. They are more fictionally inclined regardless of where they originate from.

For this reason, a hypothesis holds much more weight than a prediction. It sticks to the scientific method rather than pure guesswork. "Planets revolve around the Sun." is an example of a hypothesis as it is previous knowledge and observed trends. Additionally, we can test it through the scientific method.

Whereas "COVID-19 will be eradicated by 2030." is a prediction. Even though it results from past trends, we can't prove or disprove it. So, the only way this gets validated is to wait and watch if COVID-19 cases end by 2030.

Finally, How to Write a Hypothesis

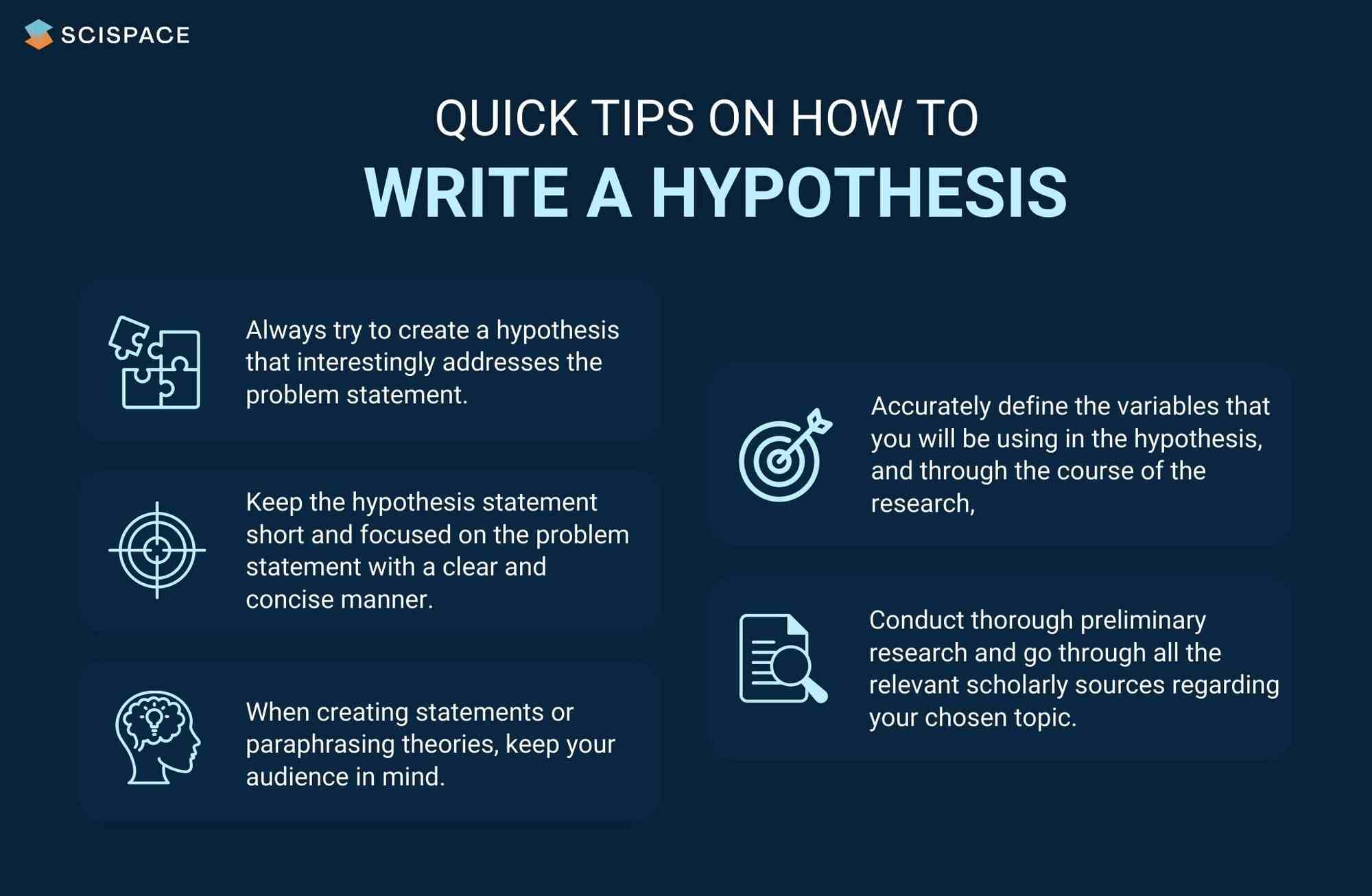

Quick tips on writing a hypothesis

1. Be clear about your research question

A hypothesis should instantly address the research question or the problem statement. To do so, you need to ask a question. Understand the constraints of your undertaken research topic and then formulate a simple and topic-centric problem. Only after that can you develop a hypothesis and further test for evidence.

2. Carry out a recce

Once you have your research's foundation laid out, it would be best to conduct preliminary research. Go through previous theories, academic papers, data, and experiments before you start curating your research hypothesis. It will give you an idea of your hypothesis's viability or originality.

Making use of references from relevant research papers helps draft a good research hypothesis. SciSpace Discover offers a repository of over 270 million research papers to browse through and gain a deeper understanding of related studies on a particular topic. Additionally, you can use SciSpace Copilot , your AI research assistant, for reading any lengthy research paper and getting a more summarized context of it. A hypothesis can be formed after evaluating many such summarized research papers. Copilot also offers explanations for theories and equations, explains paper in simplified version, allows you to highlight any text in the paper or clip math equations and tables and provides a deeper, clear understanding of what is being said. This can improve the hypothesis by helping you identify potential research gaps.

3. Create a 3-dimensional hypothesis

Variables are an essential part of any reasonable hypothesis. So, identify your independent and dependent variable(s) and form a correlation between them. The ideal way to do this is to write the hypothetical assumption in the ‘if-then' form. If you use this form, make sure that you state the predefined relationship between the variables.

In another way, you can choose to present your hypothesis as a comparison between two variables. Here, you must specify the difference you expect to observe in the results.

4. Write the first draft

Now that everything is in place, it's time to write your hypothesis. For starters, create the first draft. In this version, write what you expect to find from your research.

Clearly separate your independent and dependent variables and the link between them. Don't fixate on syntax at this stage. The goal is to ensure your hypothesis addresses the issue.

5. Proof your hypothesis

After preparing the first draft of your hypothesis, you need to inspect it thoroughly. It should tick all the boxes, like being concise, straightforward, relevant, and accurate. Your final hypothesis has to be well-structured as well.

Research projects are an exciting and crucial part of being a scholar. And once you have your research question, you need a great hypothesis to begin conducting research. Thus, knowing how to write a hypothesis is very important.

Now that you have a firmer grasp on what a good hypothesis constitutes, the different kinds there are, and what process to follow, you will find it much easier to write your hypothesis, which ultimately helps your research.

Now it's easier than ever to streamline your research workflow with SciSpace Discover . Its integrated, comprehensive end-to-end platform for research allows scholars to easily discover, write and publish their research and fosters collaboration.

It includes everything you need, including a repository of over 270 million research papers across disciplines, SEO-optimized summaries and public profiles to show your expertise and experience.

If you found these tips on writing a research hypothesis useful, head over to our blog on Statistical Hypothesis Testing to learn about the top researchers, papers, and institutions in this domain.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. what is the definition of hypothesis.

According to the Oxford dictionary, a hypothesis is defined as “An idea or explanation of something that is based on a few known facts, but that has not yet been proved to be true or correct”.

2. What is an example of hypothesis?

The hypothesis is a statement that proposes a relationship between two or more variables. An example: "If we increase the number of new users who join our platform by 25%, then we will see an increase in revenue."

3. What is an example of null hypothesis?

A null hypothesis is a statement that there is no relationship between two variables. The null hypothesis is written as H0. The null hypothesis states that there is no effect. For example, if you're studying whether or not a particular type of exercise increases strength, your null hypothesis will be "there is no difference in strength between people who exercise and people who don't."

4. What are the types of research?

• Fundamental research

• Applied research

• Qualitative research

• Quantitative research

• Mixed research

• Exploratory research

• Longitudinal research

• Cross-sectional research

• Field research

• Laboratory research

• Fixed research

• Flexible research

• Action research

• Policy research

• Classification research

• Comparative research

• Causal research

• Inductive research

• Deductive research

5. How to write a hypothesis?

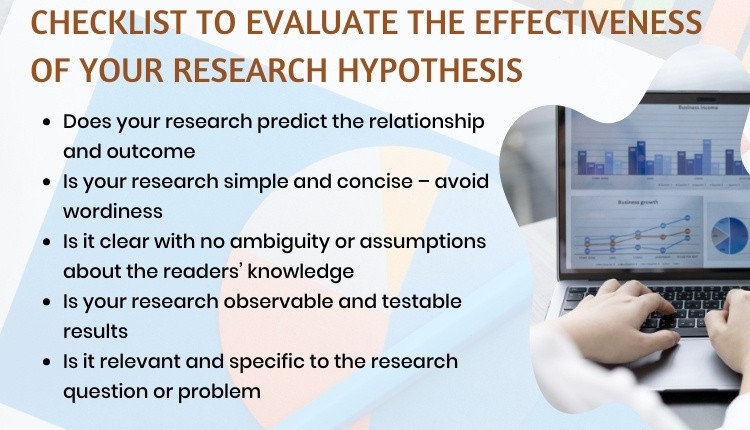

• Your hypothesis should be able to predict the relationship and outcome.

• Avoid wordiness by keeping it simple and brief.

• Your hypothesis should contain observable and testable outcomes.

• Your hypothesis should be relevant to the research question.

6. What are the 2 types of hypothesis?

• Null hypotheses are used to test the claim that "there is no difference between two groups of data".

• Alternative hypotheses test the claim that "there is a difference between two data groups".

7. Difference between research question and research hypothesis?

A research question is a broad, open-ended question you will try to answer through your research. A hypothesis is a statement based on prior research or theory that you expect to be true due to your study. Example - Research question: What are the factors that influence the adoption of the new technology? Research hypothesis: There is a positive relationship between age, education and income level with the adoption of the new technology.

8. What is plural for hypothesis?

The plural of hypothesis is hypotheses. Here's an example of how it would be used in a statement, "Numerous well-considered hypotheses are presented in this part, and they are supported by tables and figures that are well-illustrated."

9. What is the red queen hypothesis?

The red queen hypothesis in evolutionary biology states that species must constantly evolve to avoid extinction because if they don't, they will be outcompeted by other species that are evolving. Leigh Van Valen first proposed it in 1973; since then, it has been tested and substantiated many times.

10. Who is known as the father of null hypothesis?

The father of the null hypothesis is Sir Ronald Fisher. He published a paper in 1925 that introduced the concept of null hypothesis testing, and he was also the first to use the term itself.

11. When to reject null hypothesis?

You need to find a significant difference between your two populations to reject the null hypothesis. You can determine that by running statistical tests such as an independent sample t-test or a dependent sample t-test. You should reject the null hypothesis if the p-value is less than 0.05.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What is a Research Hypothesis: How to Write it, Types, and Examples

Any research begins with a research question and a research hypothesis . A research question alone may not suffice to design the experiment(s) needed to answer it. A hypothesis is central to the scientific method. But what is a hypothesis ? A hypothesis is a testable statement that proposes a possible explanation to a phenomenon, and it may include a prediction. Next, you may ask what is a research hypothesis ? Simply put, a research hypothesis is a prediction or educated guess about the relationship between the variables that you want to investigate.

It is important to be thorough when developing your research hypothesis. Shortcomings in the framing of a hypothesis can affect the study design and the results. A better understanding of the research hypothesis definition and characteristics of a good hypothesis will make it easier for you to develop your own hypothesis for your research. Let’s dive in to know more about the types of research hypothesis , how to write a research hypothesis , and some research hypothesis examples .

Table of Contents

What is a hypothesis ?

A hypothesis is based on the existing body of knowledge in a study area. Framed before the data are collected, a hypothesis states the tentative relationship between independent and dependent variables, along with a prediction of the outcome.

What is a research hypothesis ?

Young researchers starting out their journey are usually brimming with questions like “ What is a hypothesis ?” “ What is a research hypothesis ?” “How can I write a good research hypothesis ?”

A research hypothesis is a statement that proposes a possible explanation for an observable phenomenon or pattern. It guides the direction of a study and predicts the outcome of the investigation. A research hypothesis is testable, i.e., it can be supported or disproven through experimentation or observation.

Characteristics of a good hypothesis

Here are the characteristics of a good hypothesis :

- Clearly formulated and free of language errors and ambiguity

- Concise and not unnecessarily verbose

- Has clearly defined variables

- Testable and stated in a way that allows for it to be disproven

- Can be tested using a research design that is feasible, ethical, and practical

- Specific and relevant to the research problem

- Rooted in a thorough literature search

- Can generate new knowledge or understanding.

How to create an effective research hypothesis

A study begins with the formulation of a research question. A researcher then performs background research. This background information forms the basis for building a good research hypothesis . The researcher then performs experiments, collects, and analyzes the data, interprets the findings, and ultimately, determines if the findings support or negate the original hypothesis.

Let’s look at each step for creating an effective, testable, and good research hypothesis :

- Identify a research problem or question: Start by identifying a specific research problem.

- Review the literature: Conduct an in-depth review of the existing literature related to the research problem to grasp the current knowledge and gaps in the field.

- Formulate a clear and testable hypothesis : Based on the research question, use existing knowledge to form a clear and testable hypothesis . The hypothesis should state a predicted relationship between two or more variables that can be measured and manipulated. Improve the original draft till it is clear and meaningful.

- State the null hypothesis: The null hypothesis is a statement that there is no relationship between the variables you are studying.

- Define the population and sample: Clearly define the population you are studying and the sample you will be using for your research.

- Select appropriate methods for testing the hypothesis: Select appropriate research methods, such as experiments, surveys, or observational studies, which will allow you to test your research hypothesis .

Remember that creating a research hypothesis is an iterative process, i.e., you might have to revise it based on the data you collect. You may need to test and reject several hypotheses before answering the research problem.

How to write a research hypothesis

When you start writing a research hypothesis , you use an “if–then” statement format, which states the predicted relationship between two or more variables. Clearly identify the independent variables (the variables being changed) and the dependent variables (the variables being measured), as well as the population you are studying. Review and revise your hypothesis as needed.

An example of a research hypothesis in this format is as follows:

“ If [athletes] follow [cold water showers daily], then their [endurance] increases.”

Population: athletes

Independent variable: daily cold water showers

Dependent variable: endurance

You may have understood the characteristics of a good hypothesis . But note that a research hypothesis is not always confirmed; a researcher should be prepared to accept or reject the hypothesis based on the study findings.

Research hypothesis checklist

Following from above, here is a 10-point checklist for a good research hypothesis :

- Testable: A research hypothesis should be able to be tested via experimentation or observation.

- Specific: A research hypothesis should clearly state the relationship between the variables being studied.

- Based on prior research: A research hypothesis should be based on existing knowledge and previous research in the field.

- Falsifiable: A research hypothesis should be able to be disproven through testing.

- Clear and concise: A research hypothesis should be stated in a clear and concise manner.

- Logical: A research hypothesis should be logical and consistent with current understanding of the subject.

- Relevant: A research hypothesis should be relevant to the research question and objectives.

- Feasible: A research hypothesis should be feasible to test within the scope of the study.

- Reflects the population: A research hypothesis should consider the population or sample being studied.

- Uncomplicated: A good research hypothesis is written in a way that is easy for the target audience to understand.

By following this research hypothesis checklist , you will be able to create a research hypothesis that is strong, well-constructed, and more likely to yield meaningful results.

Types of research hypothesis

Different types of research hypothesis are used in scientific research:

1. Null hypothesis:

A null hypothesis states that there is no change in the dependent variable due to changes to the independent variable. This means that the results are due to chance and are not significant. A null hypothesis is denoted as H0 and is stated as the opposite of what the alternative hypothesis states.

Example: “ The newly identified virus is not zoonotic .”

2. Alternative hypothesis:

This states that there is a significant difference or relationship between the variables being studied. It is denoted as H1 or Ha and is usually accepted or rejected in favor of the null hypothesis.

Example: “ The newly identified virus is zoonotic .”

3. Directional hypothesis :

This specifies the direction of the relationship or difference between variables; therefore, it tends to use terms like increase, decrease, positive, negative, more, or less.

Example: “ The inclusion of intervention X decreases infant mortality compared to the original treatment .”

4. Non-directional hypothesis:

While it does not predict the exact direction or nature of the relationship between the two variables, a non-directional hypothesis states the existence of a relationship or difference between variables but not the direction, nature, or magnitude of the relationship. A non-directional hypothesis may be used when there is no underlying theory or when findings contradict previous research.

Example, “ Cats and dogs differ in the amount of affection they express .”

5. Simple hypothesis :

A simple hypothesis only predicts the relationship between one independent and another independent variable.

Example: “ Applying sunscreen every day slows skin aging .”

6 . Complex hypothesis :

A complex hypothesis states the relationship or difference between two or more independent and dependent variables.

Example: “ Applying sunscreen every day slows skin aging, reduces sun burn, and reduces the chances of skin cancer .” (Here, the three dependent variables are slowing skin aging, reducing sun burn, and reducing the chances of skin cancer.)

7. Associative hypothesis:

An associative hypothesis states that a change in one variable results in the change of the other variable. The associative hypothesis defines interdependency between variables.

Example: “ There is a positive association between physical activity levels and overall health .”

8 . Causal hypothesis:

A causal hypothesis proposes a cause-and-effect interaction between variables.

Example: “ Long-term alcohol use causes liver damage .”

Note that some of the types of research hypothesis mentioned above might overlap. The types of hypothesis chosen will depend on the research question and the objective of the study.

Research hypothesis examples

Here are some good research hypothesis examples :

“The use of a specific type of therapy will lead to a reduction in symptoms of depression in individuals with a history of major depressive disorder.”

“Providing educational interventions on healthy eating habits will result in weight loss in overweight individuals.”

“Plants that are exposed to certain types of music will grow taller than those that are not exposed to music.”

“The use of the plant growth regulator X will lead to an increase in the number of flowers produced by plants.”

Characteristics that make a research hypothesis weak are unclear variables, unoriginality, being too general or too vague, and being untestable. A weak hypothesis leads to weak research and improper methods.

Some bad research hypothesis examples (and the reasons why they are “bad”) are as follows:

“This study will show that treatment X is better than any other treatment . ” (This statement is not testable, too broad, and does not consider other treatments that may be effective.)

“This study will prove that this type of therapy is effective for all mental disorders . ” (This statement is too broad and not testable as mental disorders are complex and different disorders may respond differently to different types of therapy.)

“Plants can communicate with each other through telepathy . ” (This statement is not testable and lacks a scientific basis.)

Importance of testable hypothesis

If a research hypothesis is not testable, the results will not prove or disprove anything meaningful. The conclusions will be vague at best. A testable hypothesis helps a researcher focus on the study outcome and understand the implication of the question and the different variables involved. A testable hypothesis helps a researcher make precise predictions based on prior research.

To be considered testable, there must be a way to prove that the hypothesis is true or false; further, the results of the hypothesis must be reproducible.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on research hypothesis

1. What is the difference between research question and research hypothesis ?

A research question defines the problem and helps outline the study objective(s). It is an open-ended statement that is exploratory or probing in nature. Therefore, it does not make predictions or assumptions. It helps a researcher identify what information to collect. A research hypothesis , however, is a specific, testable prediction about the relationship between variables. Accordingly, it guides the study design and data analysis approach.

2. When to reject null hypothesis ?

A null hypothesis should be rejected when the evidence from a statistical test shows that it is unlikely to be true. This happens when the test statistic (e.g., p -value) is less than the defined significance level (e.g., 0.05). Rejecting the null hypothesis does not necessarily mean that the alternative hypothesis is true; it simply means that the evidence found is not compatible with the null hypothesis.

3. How can I be sure my hypothesis is testable?

A testable hypothesis should be specific and measurable, and it should state a clear relationship between variables that can be tested with data. To ensure that your hypothesis is testable, consider the following:

- Clearly define the key variables in your hypothesis. You should be able to measure and manipulate these variables in a way that allows you to test the hypothesis.

- The hypothesis should predict a specific outcome or relationship between variables that can be measured or quantified.

- You should be able to collect the necessary data within the constraints of your study.

- It should be possible for other researchers to replicate your study, using the same methods and variables.

- Your hypothesis should be testable by using appropriate statistical analysis techniques, so you can draw conclusions, and make inferences about the population from the sample data.

- The hypothesis should be able to be disproven or rejected through the collection of data.

4. How do I revise my research hypothesis if my data does not support it?

If your data does not support your research hypothesis , you will need to revise it or develop a new one. You should examine your data carefully and identify any patterns or anomalies, re-examine your research question, and/or revisit your theory to look for any alternative explanations for your results. Based on your review of the data, literature, and theories, modify your research hypothesis to better align it with the results you obtained. Use your revised hypothesis to guide your research design and data collection. It is important to remain objective throughout the process.

5. I am performing exploratory research. Do I need to formulate a research hypothesis?

As opposed to “confirmatory” research, where a researcher has some idea about the relationship between the variables under investigation, exploratory research (or hypothesis-generating research) looks into a completely new topic about which limited information is available. Therefore, the researcher will not have any prior hypotheses. In such cases, a researcher will need to develop a post-hoc hypothesis. A post-hoc research hypothesis is generated after these results are known.

6. How is a research hypothesis different from a research question?

A research question is an inquiry about a specific topic or phenomenon, typically expressed as a question. It seeks to explore and understand a particular aspect of the research subject. In contrast, a research hypothesis is a specific statement or prediction that suggests an expected relationship between variables. It is formulated based on existing knowledge or theories and guides the research design and data analysis.

7. Can a research hypothesis change during the research process?

Yes, research hypotheses can change during the research process. As researchers collect and analyze data, new insights and information may emerge that require modification or refinement of the initial hypotheses. This can be due to unexpected findings, limitations in the original hypotheses, or the need to explore additional dimensions of the research topic. Flexibility is crucial in research, allowing for adaptation and adjustment of hypotheses to align with the evolving understanding of the subject matter.

8. How many hypotheses should be included in a research study?

The number of research hypotheses in a research study varies depending on the nature and scope of the research. It is not necessary to have multiple hypotheses in every study. Some studies may have only one primary hypothesis, while others may have several related hypotheses. The number of hypotheses should be determined based on the research objectives, research questions, and the complexity of the research topic. It is important to ensure that the hypotheses are focused, testable, and directly related to the research aims.

9. Can research hypotheses be used in qualitative research?

Yes, research hypotheses can be used in qualitative research, although they are more commonly associated with quantitative research. In qualitative research, hypotheses may be formulated as tentative or exploratory statements that guide the investigation. Instead of testing hypotheses through statistical analysis, qualitative researchers may use the hypotheses to guide data collection and analysis, seeking to uncover patterns, themes, or relationships within the qualitative data. The emphasis in qualitative research is often on generating insights and understanding rather than confirming or rejecting specific research hypotheses through statistical testing.

Editage All Access is a subscription-based platform that unifies the best AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline every step of a researcher’s journey. The Editage All Access Pack is a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI writing assistant, literature recommender, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional publication services from Editage.

Based on 22+ years of experience in academia, Editage All Access empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success. Explore our top AI Tools pack, AI Tools + Publication Services pack, or Build Your Own Plan. Find everything a researcher needs to succeed, all in one place – Get All Access now starting at just $14 a month !

Related Posts

Back to School – Lock-in All Access Pack for a Year at the Best Price

Research Paper Appendix: Format and Examples

What Is A Research (Scientific) Hypothesis? A plain-language explainer + examples

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

If you’re new to the world of research, or it’s your first time writing a dissertation or thesis, you’re probably noticing that the words “research hypothesis” and “scientific hypothesis” are used quite a bit, and you’re wondering what they mean in a research context .

“Hypothesis” is one of those words that people use loosely, thinking they understand what it means. However, it has a very specific meaning within academic research. So, it’s important to understand the exact meaning before you start hypothesizing.

Research Hypothesis 101

- What is a hypothesis ?

- What is a research hypothesis (scientific hypothesis)?

- Requirements for a research hypothesis

- Definition of a research hypothesis

- The null hypothesis

What is a hypothesis?

Let’s start with the general definition of a hypothesis (not a research hypothesis or scientific hypothesis), according to the Cambridge Dictionary:

Hypothesis: an idea or explanation for something that is based on known facts but has not yet been proved.

In other words, it’s a statement that provides an explanation for why or how something works, based on facts (or some reasonable assumptions), but that has not yet been specifically tested . For example, a hypothesis might look something like this:

Hypothesis: sleep impacts academic performance.

This statement predicts that academic performance will be influenced by the amount and/or quality of sleep a student engages in – sounds reasonable, right? It’s based on reasonable assumptions , underpinned by what we currently know about sleep and health (from the existing literature). So, loosely speaking, we could call it a hypothesis, at least by the dictionary definition.

But that’s not good enough…

Unfortunately, that’s not quite sophisticated enough to describe a research hypothesis (also sometimes called a scientific hypothesis), and it wouldn’t be acceptable in a dissertation, thesis or research paper . In the world of academic research, a statement needs a few more criteria to constitute a true research hypothesis .

What is a research hypothesis?

A research hypothesis (also called a scientific hypothesis) is a statement about the expected outcome of a study (for example, a dissertation or thesis). To constitute a quality hypothesis, the statement needs to have three attributes – specificity , clarity and testability .

Let’s take a look at these more closely.

Need a helping hand?

Hypothesis Essential #1: Specificity & Clarity

A good research hypothesis needs to be extremely clear and articulate about both what’ s being assessed (who or what variables are involved ) and the expected outcome (for example, a difference between groups, a relationship between variables, etc.).

Let’s stick with our sleepy students example and look at how this statement could be more specific and clear.

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

As you can see, the statement is very specific as it identifies the variables involved (sleep hours and test grades), the parties involved (two groups of students), as well as the predicted relationship type (a positive relationship). There’s no ambiguity or uncertainty about who or what is involved in the statement, and the expected outcome is clear.

Contrast that to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – and you can see the difference. “Sleep” and “academic performance” are both comparatively vague , and there’s no indication of what the expected relationship direction is (more sleep or less sleep). As you can see, specificity and clarity are key.

Hypothesis Essential #2: Testability (Provability)

A statement must be testable to qualify as a research hypothesis. In other words, there needs to be a way to prove (or disprove) the statement. If it’s not testable, it’s not a hypothesis – simple as that.

For example, consider the hypothesis we mentioned earlier:

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

We could test this statement by undertaking a quantitative study involving two groups of students, one that gets 8 or more hours of sleep per night for a fixed period, and one that gets less. We could then compare the standardised test results for both groups to see if there’s a statistically significant difference.

Again, if you compare this to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – you can see that it would be quite difficult to test that statement, primarily because it isn’t specific enough. How much sleep? By who? What type of academic performance?

So, remember the mantra – if you can’t test it, it’s not a hypothesis 🙂

Defining A Research Hypothesis

You’re still with us? Great! Let’s recap and pin down a clear definition of a hypothesis.

A research hypothesis (or scientific hypothesis) is a statement about an expected relationship between variables, or explanation of an occurrence, that is clear, specific and testable.

So, when you write up hypotheses for your dissertation or thesis, make sure that they meet all these criteria. If you do, you’ll not only have rock-solid hypotheses but you’ll also ensure a clear focus for your entire research project.

What about the null hypothesis?

You may have also heard the terms null hypothesis , alternative hypothesis, or H-zero thrown around. At a simple level, the null hypothesis is the counter-proposal to the original hypothesis.

For example, if the hypothesis predicts that there is a relationship between two variables (for example, sleep and academic performance), the null hypothesis would predict that there is no relationship between those variables.

At a more technical level, the null hypothesis proposes that no statistical significance exists in a set of given observations and that any differences are due to chance alone.

And there you have it – hypotheses in a nutshell.

If you have any questions, be sure to leave a comment below and we’ll do our best to help you. If you need hands-on help developing and testing your hypotheses, consider our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the research journey.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

17 Comments

Very useful information. I benefit more from getting more information in this regard.

Very great insight,educative and informative. Please give meet deep critics on many research data of public international Law like human rights, environment, natural resources, law of the sea etc

In a book I read a distinction is made between null, research, and alternative hypothesis. As far as I understand, alternative and research hypotheses are the same. Can you please elaborate? Best Afshin

This is a self explanatory, easy going site. I will recommend this to my friends and colleagues.

Very good definition. How can I cite your definition in my thesis? Thank you. Is nul hypothesis compulsory in a research?

It’s a counter-proposal to be proven as a rejection

Please what is the difference between alternate hypothesis and research hypothesis?

It is a very good explanation. However, it limits hypotheses to statistically tasteable ideas. What about for qualitative researches or other researches that involve quantitative data that don’t need statistical tests?

In qualitative research, one typically uses propositions, not hypotheses.

could you please elaborate it more

I’ve benefited greatly from these notes, thank you.

This is very helpful

well articulated ideas are presented here, thank you for being reliable sources of information

Excellent. Thanks for being clear and sound about the research methodology and hypothesis (quantitative research)

I have only a simple question regarding the null hypothesis. – Is the null hypothesis (Ho) known as the reversible hypothesis of the alternative hypothesis (H1? – How to test it in academic research?

this is very important note help me much more

Hi” best wishes to you and your very nice blog”

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- What Is Research Methodology? Simple Definition (With Examples) - Grad Coach - […] Contrasted to this, a quantitative methodology is typically used when the research aims and objectives are confirmatory in nature. For example,…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples

How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples

Published on May 6, 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested by scientific research. If you want to test a relationship between two or more variables, you need to write hypotheses before you start your experiment or data collection .

Example: Hypothesis

Daily apple consumption leads to fewer doctor’s visits.

Table of contents

What is a hypothesis, developing a hypothesis (with example), hypothesis examples, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about writing hypotheses.

A hypothesis states your predictions about what your research will find. It is a tentative answer to your research question that has not yet been tested. For some research projects, you might have to write several hypotheses that address different aspects of your research question.

A hypothesis is not just a guess – it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations and statistical analysis of data).

Variables in hypotheses

Hypotheses propose a relationship between two or more types of variables .

- An independent variable is something the researcher changes or controls.

- A dependent variable is something the researcher observes and measures.

If there are any control variables , extraneous variables , or confounding variables , be sure to jot those down as you go to minimize the chances that research bias will affect your results.

In this example, the independent variable is exposure to the sun – the assumed cause . The dependent variable is the level of happiness – the assumed effect .

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Step 1. Ask a question

Writing a hypothesis begins with a research question that you want to answer. The question should be focused, specific, and researchable within the constraints of your project.

Step 2. Do some preliminary research

Your initial answer to the question should be based on what is already known about the topic. Look for theories and previous studies to help you form educated assumptions about what your research will find.

At this stage, you might construct a conceptual framework to ensure that you’re embarking on a relevant topic . This can also help you identify which variables you will study and what you think the relationships are between them. Sometimes, you’ll have to operationalize more complex constructs.

Step 3. Formulate your hypothesis

Now you should have some idea of what you expect to find. Write your initial answer to the question in a clear, concise sentence.

4. Refine your hypothesis

You need to make sure your hypothesis is specific and testable. There are various ways of phrasing a hypothesis, but all the terms you use should have clear definitions, and the hypothesis should contain:

- The relevant variables

- The specific group being studied

- The predicted outcome of the experiment or analysis

5. Phrase your hypothesis in three ways

To identify the variables, you can write a simple prediction in if…then form. The first part of the sentence states the independent variable and the second part states the dependent variable.

In academic research, hypotheses are more commonly phrased in terms of correlations or effects, where you directly state the predicted relationship between variables.

If you are comparing two groups, the hypothesis can state what difference you expect to find between them.

6. Write a null hypothesis

If your research involves statistical hypothesis testing , you will also have to write a null hypothesis . The null hypothesis is the default position that there is no association between the variables. The null hypothesis is written as H 0 , while the alternative hypothesis is H 1 or H a .

- H 0 : The number of lectures attended by first-year students has no effect on their final exam scores.

- H 1 : The number of lectures attended by first-year students has a positive effect on their final exam scores.

| Research question | Hypothesis | Null hypothesis |

|---|---|---|

| What are the health benefits of eating an apple a day? | Increasing apple consumption in over-60s will result in decreasing frequency of doctor’s visits. | Increasing apple consumption in over-60s will have no effect on frequency of doctor’s visits. |

| Which airlines have the most delays? | Low-cost airlines are more likely to have delays than premium airlines. | Low-cost and premium airlines are equally likely to have delays. |

| Can flexible work arrangements improve job satisfaction? | Employees who have flexible working hours will report greater job satisfaction than employees who work fixed hours. | There is no relationship between working hour flexibility and job satisfaction. |

| How effective is high school sex education at reducing teen pregnancies? | Teenagers who received sex education lessons throughout high school will have lower rates of unplanned pregnancy teenagers who did not receive any sex education. | High school sex education has no effect on teen pregnancy rates. |

| What effect does daily use of social media have on the attention span of under-16s? | There is a negative between time spent on social media and attention span in under-16s. | There is no relationship between social media use and attention span in under-16s. |

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

A hypothesis is not just a guess — it should be based on existing theories and knowledge. It also has to be testable, which means you can support or refute it through scientific research methods (such as experiments, observations and statistical analysis of data).

Null and alternative hypotheses are used in statistical hypothesis testing . The null hypothesis of a test always predicts no effect or no relationship between variables, while the alternative hypothesis states your research prediction of an effect or relationship.

Hypothesis testing is a formal procedure for investigating our ideas about the world using statistics. It is used by scientists to test specific predictions, called hypotheses , by calculating how likely it is that a pattern or relationship between variables could have arisen by chance.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). How to Write a Strong Hypothesis | Steps & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 28, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/hypothesis/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, construct validity | definition, types, & examples, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples, operationalization | a guide with examples, pros & cons, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Research Hypothesis: What It Is, Types + How to Develop?

A research study starts with a question. Researchers worldwide ask questions and create research hypotheses. The effectiveness of research relies on developing a good research hypothesis. Examples of research hypotheses can guide researchers in writing effective ones.

In this blog, we’ll learn what a research hypothesis is, why it’s important in research, and the different types used in science. We’ll also guide you through creating your research hypothesis and discussing ways to test and evaluate it.

What is a Research Hypothesis?

A hypothesis is like a guess or idea that you suggest to check if it’s true. A research hypothesis is a statement that brings up a question and predicts what might happen.

It’s really important in the scientific method and is used in experiments to figure things out. Essentially, it’s an educated guess about how things are connected in the research.

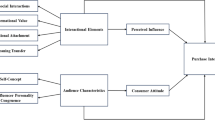

A research hypothesis usually includes pointing out the independent variable (the thing they’re changing or studying) and the dependent variable (the result they’re measuring or watching). It helps plan how to gather and analyze data to see if there’s evidence to support or deny the expected connection between these variables.

Importance of Hypothesis in Research

Hypotheses are really important in research. They help design studies, allow for practical testing, and add to our scientific knowledge. Their main role is to organize research projects, making them purposeful, focused, and valuable to the scientific community. Let’s look at some key reasons why they matter:

- A research hypothesis helps test theories.

A hypothesis plays a pivotal role in the scientific method by providing a basis for testing existing theories. For example, a hypothesis might test the predictive power of a psychological theory on human behavior.

- It serves as a great platform for investigation activities.

It serves as a launching pad for investigation activities, which offers researchers a clear starting point. A research hypothesis can explore the relationship between exercise and stress reduction.

- Hypothesis guides the research work or study.

A well-formulated hypothesis guides the entire research process. It ensures that the study remains focused and purposeful. For instance, a hypothesis about the impact of social media on interpersonal relationships provides clear guidance for a study.

- Hypothesis sometimes suggests theories.

In some cases, a hypothesis can suggest new theories or modifications to existing ones. For example, a hypothesis testing the effectiveness of a new drug might prompt a reconsideration of current medical theories.

- It helps in knowing the data needs.

A hypothesis clarifies the data requirements for a study, ensuring that researchers collect the necessary information—a hypothesis guiding the collection of demographic data to analyze the influence of age on a particular phenomenon.

- The hypothesis explains social phenomena.

Hypotheses are instrumental in explaining complex social phenomena. For instance, a hypothesis might explore the relationship between economic factors and crime rates in a given community.

- Hypothesis provides a relationship between phenomena for empirical Testing.

Hypotheses establish clear relationships between phenomena, paving the way for empirical testing. An example could be a hypothesis exploring the correlation between sleep patterns and academic performance.

- It helps in knowing the most suitable analysis technique.

A hypothesis guides researchers in selecting the most appropriate analysis techniques for their data. For example, a hypothesis focusing on the effectiveness of a teaching method may lead to the choice of statistical analyses best suited for educational research.

Characteristics of a Good Research Hypothesis

A hypothesis is a specific idea that you can test in a study. It often comes from looking at past research and theories. A good hypothesis usually starts with a research question that you can explore through background research. For it to be effective, consider these key characteristics:

- Clear and Focused Language: A good hypothesis uses clear and focused language to avoid confusion and ensure everyone understands it.

- Related to the Research Topic: The hypothesis should directly relate to the research topic, acting as a bridge between the specific question and the broader study.

- Testable: An effective hypothesis can be tested, meaning its prediction can be checked with real data to support or challenge the proposed relationship.

- Potential for Exploration: A good hypothesis often comes from a research question that invites further exploration. Doing background research helps find gaps and potential areas to investigate.

- Includes Variables: The hypothesis should clearly state both the independent and dependent variables, specifying the factors being studied and the expected outcomes.

- Ethical Considerations: Check if variables can be manipulated without breaking ethical standards. It’s crucial to maintain ethical research practices.

- Predicts Outcomes: The hypothesis should predict the expected relationship and outcome, acting as a roadmap for the study and guiding data collection and analysis.

- Simple and Concise: A good hypothesis avoids unnecessary complexity and is simple and concise, expressing the essence of the proposed relationship clearly.

- Clear and Assumption-Free: The hypothesis should be clear and free from assumptions about the reader’s prior knowledge, ensuring universal understanding.

- Observable and Testable Results: A strong hypothesis implies research that produces observable and testable results, making sure the study’s outcomes can be effectively measured and analyzed.

When you use these characteristics as a checklist, it can help you create a good research hypothesis. It’ll guide improving and strengthening the hypothesis, identifying any weaknesses, and making necessary changes. Crafting a hypothesis with these features helps you conduct a thorough and insightful research study.

Types of Research Hypotheses

The research hypothesis comes in various types, each serving a specific purpose in guiding the scientific investigation. Knowing the differences will make it easier for you to create your own hypothesis. Here’s an overview of the common types:

01. Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis states that there is no connection between two considered variables or that two groups are unrelated. As discussed earlier, a hypothesis is an unproven assumption lacking sufficient supporting data. It serves as the statement researchers aim to disprove. It is testable, verifiable, and can be rejected.

For example, if you’re studying the relationship between Project A and Project B, assuming both projects are of equal standard is your null hypothesis. It needs to be specific for your study.

02. Alternative Hypothesis

The alternative hypothesis is basically another option to the null hypothesis. It involves looking for a significant change or alternative that could lead you to reject the null hypothesis. It’s a different idea compared to the null hypothesis.

When you create a null hypothesis, you’re making an educated guess about whether something is true or if there’s a connection between that thing and another variable. If the null view suggests something is correct, the alternative hypothesis says it’s incorrect.

For instance, if your null hypothesis is “I’m going to be $1000 richer,” the alternative hypothesis would be “I’m not going to get $1000 or be richer.”

03. Directional Hypothesis

The directional hypothesis predicts the direction of the relationship between independent and dependent variables. They specify whether the effect will be positive or negative.

If you increase your study hours, you will experience a positive association with your exam scores. This hypothesis suggests that as you increase the independent variable (study hours), there will also be an increase in the dependent variable (exam scores).

04. Non-directional Hypothesis

The non-directional hypothesis predicts the existence of a relationship between variables but does not specify the direction of the effect. It suggests that there will be a significant difference or relationship, but it does not predict the nature of that difference.

For example, you will find no notable difference in test scores between students who receive the educational intervention and those who do not. However, once you compare the test scores of the two groups, you will notice an important difference.

05. Simple Hypothesis

A simple hypothesis predicts a relationship between one dependent variable and one independent variable without specifying the nature of that relationship. It’s simple and usually used when we don’t know much about how the two things are connected.

For example, if you adopt effective study habits, you will achieve higher exam scores than those with poor study habits.

06. Complex Hypothesis

A complex hypothesis is an idea that specifies a relationship between multiple independent and dependent variables. It is a more detailed idea than a simple hypothesis.

While a simple view suggests a straightforward cause-and-effect relationship between two things, a complex hypothesis involves many factors and how they’re connected to each other.

For example, when you increase your study time, you tend to achieve higher exam scores. The connection between your study time and exam performance is affected by various factors, including the quality of your sleep, your motivation levels, and the effectiveness of your study techniques.

If you sleep well, stay highly motivated, and use effective study strategies, you may observe a more robust positive correlation between the time you spend studying and your exam scores, unlike those who may lack these factors.

07. Associative Hypothesis

An associative hypothesis proposes a connection between two things without saying that one causes the other. Basically, it suggests that when one thing changes, the other changes too, but it doesn’t claim that one thing is causing the change in the other.

For example, you will likely notice higher exam scores when you increase your study time. You can recognize an association between your study time and exam scores in this scenario.

Your hypothesis acknowledges a relationship between the two variables—your study time and exam scores—without asserting that increased study time directly causes higher exam scores. You need to consider that other factors, like motivation or learning style, could affect the observed association.

08. Causal Hypothesis

A causal hypothesis proposes a cause-and-effect relationship between two variables. It suggests that changes in one variable directly cause changes in another variable.

For example, when you increase your study time, you experience higher exam scores. This hypothesis suggests a direct cause-and-effect relationship, indicating that the more time you spend studying, the higher your exam scores. It assumes that changes in your study time directly influence changes in your exam performance.

09. Empirical Hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is a statement based on things we can see and measure. It comes from direct observation or experiments and can be tested with real-world evidence. If an experiment proves a theory, it supports the idea and shows it’s not just a guess. This makes the statement more reliable than a wild guess.

For example, if you increase the dosage of a certain medication, you might observe a quicker recovery time for patients. Imagine you’re in charge of a clinical trial. In this trial, patients are given varying dosages of the medication, and you measure and compare their recovery times. This allows you to directly see the effects of different dosages on how fast patients recover.

This way, you can create a research hypothesis: “Increasing the dosage of a certain medication will lead to a faster recovery time for patients.”

10. Statistical Hypothesis

A statistical hypothesis is a statement or assumption about a population parameter that is the subject of an investigation. It serves as the basis for statistical analysis and testing. It is often tested using statistical methods to draw inferences about the larger population.

In a hypothesis test, statistical evidence is collected to either reject the null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis or fail to reject the null hypothesis due to insufficient evidence.

For example, let’s say you’re testing a new medicine. Your hypothesis could be that the medicine doesn’t really help patients get better. So, you collect data and use statistics to see if your guess is right or if the medicine actually makes a difference.

If the data strongly shows that the medicine does help, you say your guess was wrong, and the medicine does make a difference. But if the proof isn’t strong enough, you can stick with your original guess because you didn’t get enough evidence to change your mind.

How to Develop a Research Hypotheses?

Step 1: identify your research problem or topic..

Define the area of interest or the problem you want to investigate. Make sure it’s clear and well-defined.

Start by asking a question about your chosen topic. Consider the limitations of your research and create a straightforward problem related to your topic. Once you’ve done that, you can develop and test a hypothesis with evidence.

Step 2: Conduct a literature review

Review existing literature related to your research problem. This will help you understand the current state of knowledge in the field, identify gaps, and build a foundation for your hypothesis. Consider the following questions:

- What existing research has been conducted on your chosen topic?

- Are there any gaps or unanswered questions in the current literature?

- How will the existing literature contribute to the foundation of your research?

Step 3: Formulate your research question

Based on your literature review, create a specific and concise research question that addresses your identified problem. Your research question should be clear, focused, and relevant to your field of study.

Step 4: Identify variables

Determine the key variables involved in your research question. Variables are the factors or phenomena that you will study and manipulate to test your hypothesis.

- Independent Variable: The variable you manipulate or control.

- Dependent Variable: The variable you measure to observe the effect of the independent variable.

Step 5: State the Null hypothesis

The null hypothesis is a statement that there is no significant difference or effect. It serves as a baseline for comparison with the alternative hypothesis.

Step 6: Select appropriate methods for testing the hypothesis

Choose research methods that align with your study objectives, such as experiments, surveys, or observational studies. The selected methods enable you to test your research hypothesis effectively.

Creating a research hypothesis usually takes more than one try. Expect to make changes as you collect data. It’s normal to test and say no to a few hypotheses before you find the right answer to your research question.

Testing and Evaluating Hypotheses

Testing hypotheses is a really important part of research. It’s like the practical side of things. Here, real-world evidence will help you determine how different things are connected. Let’s explore the main steps in hypothesis testing:

- State your research hypothesis.

Before testing, clearly articulate your research hypothesis. This involves framing both a null hypothesis, suggesting no significant effect or relationship, and an alternative hypothesis, proposing the expected outcome.

- Collect data strategically.

Plan how you will gather information in a way that fits your study. Make sure your data collection method matches the things you’re studying.

Whether through surveys, observations, or experiments, this step demands precision and adherence to the established methodology. The quality of data collected directly influences the credibility of study outcomes.

- Perform an appropriate statistical test.

Choose a statistical test that aligns with the nature of your data and the hypotheses being tested. Whether it’s a t-test, chi-square test, ANOVA, or regression analysis, selecting the right statistical tool is paramount for accurate and reliable results.

- Decide if your idea was right or wrong.

Following the statistical analysis, evaluate the results in the context of your null hypothesis. You need to decide if you should reject your null hypothesis or not.

- Share what you found.

When discussing what you found in your research, be clear and organized. Say whether your idea was supported or not, and talk about what your results mean. Also, mention any limits to your study and suggest ideas for future research.

The Role of QuestionPro to Develop a Good Research Hypothesis

QuestionPro is a survey and research platform that provides tools for creating, distributing, and analyzing surveys. It plays a crucial role in the research process, especially when you’re in the initial stages of hypothesis development. Here’s how QuestionPro can help you to develop a good research hypothesis:

- Survey design and data collection: You can use the platform to create targeted questions that help you gather relevant data.

- Exploratory research: Through surveys and feedback mechanisms on QuestionPro, you can conduct exploratory research to understand the landscape of a particular subject.

- Literature review and background research: QuestionPro surveys can collect sample population opinions, experiences, and preferences. This data and a thorough literature evaluation can help you generate a well-grounded hypothesis by improving your research knowledge.

- Identifying variables: Using targeted survey questions, you can identify relevant variables related to their research topic.

- Testing assumptions: You can use surveys to informally test certain assumptions or hypotheses before formalizing a research hypothesis.

- Data analysis tools: QuestionPro provides tools for analyzing survey data. You can use these tools to identify the collected data’s patterns, correlations, or trends.

- Refining your hypotheses: As you collect data through QuestionPro, you can adjust your hypotheses based on the real-world responses you receive.

A research hypothesis is like a guide for researchers in science. It’s a well-thought-out idea that has been thoroughly tested. This idea is crucial as researchers can explore different fields, such as medicine, social sciences, and natural sciences. The research hypothesis links theories to real-world evidence and gives researchers a clear path to explore and make discoveries.

QuestionPro Research Suite is a helpful tool for researchers. It makes creating surveys, collecting data, and analyzing information easily. It supports all kinds of research, from exploring new ideas to forming hypotheses. With a focus on using data, it helps researchers do their best work.

Are you interested in learning more about QuestionPro Research Suite? Take advantage of QuestionPro’s free trial to get an initial look at its capabilities and realize the full potential of your research efforts.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Microsoft customer voice vs questionpro: choosing the best.

Aug 29, 2024

Statistical Methods: What It Is, Process, Analyze & Present

Aug 28, 2024

Velodu and QuestionPro: Connecting Data with a Human Touch

Google Forms vs QuestionPro: Which is Best for Your Needs?

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Privacy Policy

Home » What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Definition:

Hypothesis is an educated guess or proposed explanation for a phenomenon, based on some initial observations or data. It is a tentative statement that can be tested and potentially proven or disproven through further investigation and experimentation.

Hypothesis is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments and the collection and analysis of data. It is an essential element of the scientific method, as it allows researchers to make predictions about the outcome of their experiments and to test those predictions to determine their accuracy.

Types of Hypothesis

Types of Hypothesis are as follows:

Research Hypothesis

A research hypothesis is a statement that predicts a relationship between variables. It is usually formulated as a specific statement that can be tested through research, and it is often used in scientific research to guide the design of experiments.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis is a statement that assumes there is no significant difference or relationship between variables. It is often used as a starting point for testing the research hypothesis, and if the results of the study reject the null hypothesis, it suggests that there is a significant difference or relationship between variables.

Alternative Hypothesis

An alternative hypothesis is a statement that assumes there is a significant difference or relationship between variables. It is often used as an alternative to the null hypothesis and is tested against the null hypothesis to determine which statement is more accurate.

Directional Hypothesis

A directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the direction of the relationship between variables. For example, a researcher might predict that increasing the amount of exercise will result in a decrease in body weight.

Non-directional Hypothesis

A non-directional hypothesis is a statement that predicts the relationship between variables but does not specify the direction. For example, a researcher might predict that there is a relationship between the amount of exercise and body weight, but they do not specify whether increasing or decreasing exercise will affect body weight.

Statistical Hypothesis

A statistical hypothesis is a statement that assumes a particular statistical model or distribution for the data. It is often used in statistical analysis to test the significance of a particular result.

Composite Hypothesis

A composite hypothesis is a statement that assumes more than one condition or outcome. It can be divided into several sub-hypotheses, each of which represents a different possible outcome.

Empirical Hypothesis

An empirical hypothesis is a statement that is based on observed phenomena or data. It is often used in scientific research to develop theories or models that explain the observed phenomena.

Simple Hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement that assumes only one outcome or condition. It is often used in scientific research to test a single variable or factor.

Complex Hypothesis

A complex hypothesis is a statement that assumes multiple outcomes or conditions. It is often used in scientific research to test the effects of multiple variables or factors on a particular outcome.

Applications of Hypothesis

Hypotheses are used in various fields to guide research and make predictions about the outcomes of experiments or observations. Here are some examples of how hypotheses are applied in different fields:

- Science : In scientific research, hypotheses are used to test the validity of theories and models that explain natural phenomena. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a particular variable on a natural system, such as the effects of climate change on an ecosystem.

- Medicine : In medical research, hypotheses are used to test the effectiveness of treatments and therapies for specific conditions. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a new drug on a particular disease.

- Psychology : In psychology, hypotheses are used to test theories and models of human behavior and cognition. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a particular stimulus on the brain or behavior.

- Sociology : In sociology, hypotheses are used to test theories and models of social phenomena, such as the effects of social structures or institutions on human behavior. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of income inequality on crime rates.

- Business : In business research, hypotheses are used to test the validity of theories and models that explain business phenomena, such as consumer behavior or market trends. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the effects of a new marketing campaign on consumer buying behavior.

- Engineering : In engineering, hypotheses are used to test the effectiveness of new technologies or designs. For example, a hypothesis might be formulated to test the efficiency of a new solar panel design.

How to write a Hypothesis

Here are the steps to follow when writing a hypothesis:

Identify the Research Question