- Animal Rights Research Topics

- Color Blindness Topics Topics: 49

- Gender Inequality Topics Topics: 75

- Homelessness Topics Topics: 151 Research Questions

- Gender Equality Research Topics Topics: 77

- Animal Abuse Topics Topics: 97

- Animal Cruelty Essay Topics Topics: 107

- Social Inequality Research Topics Topics: 77

- Animal Testing Topics Topics: 111

- Animal Ethics Paper Topics

- Black Lives Matter Research Topics Topics: 112

- Gender Stereotypes Paper Topics Topics: 94

- Domestic Violence Topics Topics: 160

- Gender Issues Topics Topics: 101

- Social Problems Paper Topics Topics: 157

165 Karl Marx Essay Topics

🏆 best topics for essay on karl marx, ⭐ catchy karl marx essay topics, 👍 karl marx research topics & marxism essay examples, 🎓 most interesting karl marx research paper titles, 💡 simple karl marx essay ideas, 📌 easy karl marx essay topics, ❓ essay questions on marxism, 🌟 great marxism essay topics.

- Karl Marx’s and Max Weber’s Contributions to Sociology

- Durkheim and Marx: The Division of Labor

- Marx vs. Weber: Capitalism – Compare and Contrast Essay

- Liberal & Karl Marx View on Property

- Karl Marx Views on History

- Karl Marx and International Relations Theories

- Frederick Taylor’s and Karl Marx’ View of Workers

- Karl Marx and Marx Weber: Suffering in the Society This paper discusses how Karl Max and Marx Weber have explained the nature and cause of suffering in society. It also discusses Marx Weber regarding the connection between religion and capitalism.

- Hegel, Marx and Nietzsche: Comparative Analysis Marx’s view of human nature formed the basis for his philosophy. Hegel created German idealism. Nietzsche utilized topics like social criticism, psychology, religion and morality.

- Marx’s Four Types of Alienation Marx alienation focuses on the capitalist mode of production and an objective approach resulting from the reality that evolves in an individual’s knowledge in capitalist society.

- Karl Marx’s Conflict Theory and Alienation The current paper is devoted to Karl Marx’s conflict theory and the construct of alienation analysis and identifying its usefulness for social workers.

- Class and Alienation According to Marx This paper explains Karl Marx’s theory and gives the links between class and alienation, which was developed during capitalism and juxtaposes the facts against life today.

- Marx’s vs. Lenin’s Imperialism Theories The term ‘imperialism’ is often used by different scholars and theorists in varying perspectives to refer to a number of ideologies.

- Comparison and Contrast of Marx and Weber’s Theories of Capitalism The contrast promises to be necessary since capitalism is portrayed differently in the views of these two well-known sociologists.

- MacDonaldization and Marx’s Social Change Model McDonaldization is the take-up of the characteristics of a fast-food place by the society through rationalization of traditional ideologies, modes of management and thinking.

- “The Communist Manifesto” Book by Karl Marx The work “The Communist Manifesto” by Karl Marx, depicts the bourgeoisie and the proletariat and how their lives are affected by the domination of the former as a ruling class.

- Analysis of “A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy” by Marx The paper interprets a passage from Karl Marx’s work on what key concepts characterize a society and discusses the benefits and evolution from existence to conscious thinking.

- Marx’s Objections to Capitalism This essay describes and evaluates Marx’s three main objections to capitalism and criticizes them on the grounds of his underestimation of capitalism’s creative force.

- Review of Weber’s and Marx’s Theories The paper provides a detailed review of Weber’s and Marx’s theories and presents the similarities and differences between them.

- Review of “Capital” by Carl Marx In the paper special attention put on exploring the Capital and The Communist Manifesto, which are extremely important in understanding the market relationships of modern society.

- The Contribution of Karl Marx to Economics and Philosophy This paper aims to explore the contribution of Karl Marx not only to the socialist movement’s history but also to global society as it is known today.

- Karl Marx’s Fetishism of Commodities Marx examines the peculiar economic properties of market products in capitalist societies using the concept of the fetishism of commodities.

- Cruel Optimism: Karl Marx’s Ideas and the American Dream The work provides a summary and an analysis of the work of Berlant L. “Cruel optimism: On Marx, loss and the senses” in regard to Karl Marx’s ideas and the American Dream.

- Evaluating Marx’s Labor Theory of Value Evaluating Marx’s labor theory of value develops a comprehension among the public regarding the value of different commodities and respective employee wages.

- Marx: The Primitive Accumulation of Capital In the document, the author examines Marx’s point of view on the initial accumulation of capital, analyzes his arguments, and expresses his own opinion on this issue.

- Weber’s and Marx’s Views on Capitalism Comparison The purpose of this paper is to compare and contrast political theories and highlight similarities and differences between Marx and Weber.

- Karl Marx and His Contributions to Study of Economics Brief biography including dates of birth and death; details about childhood, home life, and education; and professional progress.

- Karl Marx’s Communism Manifesto Karl Marx who was a political theorist alongside another German called Friedrich Engels wrote The Communist Manifesto with the aim of improving the relationship among people.

- Analysis of Excerpts by Smith and Marx on Economic Development The article analyzes excerpts from the works of Smith and Marx in order to explain the interdependence between historical events and subsequent economic development.

- Proletariat and Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx This paper will describe the situation of the proletariat and the solution proposed by Marx to the problems of this class.

- Risk Society and Karl Marx’s Response to It A German philosopher who has been credited with the Communism introduction, Karl Marx developed a socio-political and economic theory whose impact is still felt to date.

- Karl Marx and Utopian Socialists Marx had ideas close to the Utopian ones, the ideas according to which there would be no poverty which he and his family had to live in.

- Marxism: The Communist Manifesto by Marx and Engels The Communist Manifesto by Marx and Engels can still be regarded as relevant to the nowadays political social and economic situation; however, there is no more class struggle.

- Marx’s Criticism of Capitalism and Sociological Theory This paper tells about Marx who contributed to sociological theory by linking the economic structure of the society and how it affected social interactions.

- The German Ideology by Karl Marx Karl Marx is one of the greatest contributors in the field of political ideology. His perspective of ideology was brought out clearly in the book The German Ideology.

- Karl Marx: Manifesto of the Communist Party Marx visualizes and blames the traditional feudal relationship for creating only two classes, among which the bourgeois class is the enhancement of capital over wage labor.

- The Philosophy of Karl Marx and John Stuart Mill The philosophy of Karl Marx is entirely different as compared to that of John Stuart Mill. The key ideas of Marxism relate to being alienated from a hostile capitalistic world.

- Karl Marx’s Life, Times, and Ideas in Economics Karl Marx was truly one of the most influential philosophers, economists, revolutionary and socialist thinkers of the 19th century and his work is often explored today.

- Marx’s and Weber’s Opposing Views of Capitalism Weber is among the profound critics of Marxist ideologies. They have opposing views on the issue of capitalism even though they share some similarities on the same topic.

- “The Communist Manifesto” Book by Marx and Engels The relationships between freemen and slaves are frequently discussed in modern society to find out the roots of social inequality.

- Karl Marx’s Critique of Capitalism This paper will examine the key ideas of Marx regarding class division, labor, ideology, and fetishism of commodities in the context of capitalism.

- Karl Marx and His Social Theory In his work, Marx focuses on the issues of labor and class struggle noting that the political economy has divided the society into two main classes.

- Karl Marx’ Philosophical Ideas Karl Marx’s capital is one of the most controversial theories of economic development. This theory is as a result of revelation of the Marxist philosophy.

- European Socialism: Francois Guizot, Karl Marx and Jean Jaures Practical reproduction of social differences in governance structures can make decisions that are in the best interests of the nation.

- Marx’s Labor Theory in Garnham’s and Fuchs’s Views There are different viewpoints regarding Marx’s labor theory. This paper addresses that of Nicholas Garnham and the one offered by Christian Fuchs.

- Religion in Marx’s and Nietzsche’s Philosophies This paper explores the similarities and differences between Marx and Nietzsche’s views on religion and politics.

- Karl Marx and Adam Smith’ Views on Working Class Karl Marx and Adam Smith are two prominent figures. This paper examines their works to determine which argument about perceive working class is more reasonable.

- Karl Marx’s Sociology and Its Principles In this paper, the general description of Marx’s sociology is given. A review of literature that focuses on different aspects of Marx’s theory about society is provided.

- The Vision of Capitalism: Adam Smith vs Karl Marx Comparing Smith’s vision of the impact of the capitalist economy to that of Marx, it can be claimed that the former offers a more positive evaluation of the relevant outcomes.

- Political Theorists Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

- Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto and Its Impact on Society

- Influence of Karl Marx on the Feminist Movement

- The Social and Economic Features of Jabal Nablus and Karl Marx’s Methodology

- The Similarities and Differences in the Views of Karl Marx and Max Weber

- Karl Marx: The Greatest Thinker and Philosopher of His Time

- The Life and Political Activities of Karl Marx

- Karl Marx’s Communism and How Communism Has Manifested in Russia and China

- Religion and the Perspectives of Karl Marx

- Feminist Movement and Theories of Karl Marx

- The Reasons Why the Predictions of Karl Marx Never Materialized

- The Life, Times, and Economic Contributions of Karl Marx

- Man’s Spirit Destruction and the Alienation Theory of Karl Marx

- Adam Smith and Karl Marx: Contrasting Views of Capitalism

- The Beauty and Cruelty in Human Nature: An Analysis of the Kite Runner From Biblical View and Karl Marx’s

- Karl Marx and the Industrial Revolution

- The Early Life and Philosophical Ideologies of Karl Marx

- Karl Marx and Commodity Fetishism Analysis Philosophy

- Exploring Karl Marx and Jean-Jacque Rousseau’s Views on Free

- The Similarities and Differences Between the Views of John Locke and Karl Marx on Violent Revolutions

- Political and Economic Theories of Karl Marx

- Marxism and the Marxist Theory of Karl Marx

- The Social, Political, and Economic Characteristics of Karl Marx’s Utopia in the Communist Manifesto

- The Differences and Similarities of Karl Marx‘s Theory of Anomie

- Karl Marx’s Predictions and America After the Civil War

- The Theories and Principals of Karl Marx, and the Effect His Ideas Have Had on the World Today

- Emile Durkheim and Karl Marx Views on Sociology of Religion

- Why Karl Marx Criticizes the Ideology of Capitalism?

- Karl Marx: Established Idea of Communist Society in Response to Capitalism

- Money, Interest, and Capital Accumulation in Karl Marx’s

- The Ideas and Thoughts of Karl Marx on Social and Economic Issues

- The Early Life, Achievements and Influence of Karl Marx

- Gender and Race Inequality by Karl Marx

- Karl Marx and Sigmund Freud: Human Perception and Morality

- The Most Influential Theories of Karl Marx, a German Philosopher

- The Relation Between State and Society According to Karl Marx

- Contemporary World Economy and the Communist Manifesto of Karl Marx

- Karl Marx Set the Wheels of Modern Communism and Socialism in Motion

- The Importance of Karl Marx’s Theories in Family Ethics

- Social and Economic Theories Developed by Karl Marx

- State Power and the Wrongness of Karl Marx’s Assumption

- Political Thinking and the Contributions of Karl Marx

- Society and Freedom According to Jean Jacques Rousseau and Karl Marx

- The Insights Into International Relations in the Writings of Karl Marx

- The Link Between Karl Marx and the Russian Revolution

- Why Karl Marx Thought Communism Was the Ideal Political Party

- Karl Marx’s Sociological Theories and Leadership

- The Dangers and Pitfalls of a Capitalist Regime in the Works of Karl Marx

- Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto and the Industrial Proletariat

- Religion and Education According to Max Weber and Karl Marx

- The Industrial Revolution and Karl Marx History

- The Banking School and the Monetary Thought of Karl Marx

- Karl Marx’s Social Theories and the Idea of a Temporary Worker

- Comparing and Contrasting the Role of the Market in the Political Theories of Karl Marx and Milton Friedman

- Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto and the Family Business

- Religious Controversy During the Time of Karl Marx

- Why Karl Marx and Lenin Were Influential Figures and Economic?

- Karl Marx, German Economist, and Revolutionary Socialist

- The Life and Works of Adam Smith and Karl Marx

- Karl Marx and the Impacts of Colonialism in the World History

- Modern Day International Economy and Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx

- Relationship Between Labor and Capital According to Karl Marx

- Karl Marx Rise and Fall of the Revolution

- Was Karl Marx the Biggest Talker of American Terrorist Socialist Ideals

- Karl Marx: Major Features of Capitalist Mode of Production

- Karl Marx and Marxism on Modern Thought and Society

- The Practical Cognition and the Theories of Knowledge by Karl Marx

- Karl Marx’s Socioeconomic and Political Theories

- What Would Karl Marx Say About Exploitation in Regards to Child Labour

- Karl Marx Was the Greatest Thinker and Philosopher

- The Reasons Why Karl Marx Is the Most Controversial Economic in History

- Karl Marx’s Capital Concepts Related to Labor

- Globalization and the Applicability of the Writings of Karl Marx

- Karl Marx’s Dialectical Perspectives of History

- Does Karl Marx’s Critique of Capitalism Rest on a Fallacious Philosophy of History?

- How Does Karl Marx Account for the Industrialization of Society?

- Was Karl Marx History’s Greatest Optimist?

- How Does “The Communist Manifesto” by Karl Marx Use Strong Diction?

- What Is Karl Marx Best Known For?

- Is Karl Marx a Great Thinker?

- Why Can Emile Durkheim and Karl Marx Be Regarded as Structuralists?

- What Was Karl Marx’s View of History?

- Can Feminism and Marxism Come Together?

- How Does Marxism Explain the Role of Education in Society?

- Does Marxism Adequately Explain the 1917 Russian Revolution?

- Why Was Karl Marx So Disparaging of the Utopian Socialists?

- How Did Lenin Revise Marxism?

- What Is Karl Marx’s Main Theory?

- How Does Cloud Atlas Offer an Interpretation of Marxism in a Highly Technological Society?

- What Is the Biggest Contribution of Karl Marx to the Society?

- Is Marxism Useful for Understanding Society Today?

- What Is the Main Idea Behind Karl Marx’s Theory of Socialism?

- How Much Did Stalin Deviate From Marxism?

- What Is the Famous Statement of Karl Marx?

- How Was the Status Quo Challenged by Marxism and Socialism in Russia at the Beginning of the Twentieth Century?

- Why Did Karl Marx Not Believe in God?

- What Does Marxism Tell Us About Economic Globalization Today?

- How Has Marxism Contributed to Society?

- Why Was Karl Marx So Influential in the 20th Century?

- What Role Does Culture Play in Western Marxism?

- Is Marxism Still Relevant Today?

- Why Did Western Europe Never Fully Envelope Marxism?

- How Important Was Marxism for the Development of Mozambique and Angola?

- Why Has Marxism Been Neglected for International Relations?

- Marxist Literary Criticism and its Influence on Interpretations of Classic Novels

- The Relevance of Marxism in Contemporary Societies

- Class Conflict and Power Relations in Literature: Marxist Perspective on Selected Literary Works

- Marx’s Vision of Communism: Assessing the Feasibility of a Classless Society

- The Influence of Marxist Critical Theory on Feminist Literature: Unraveling Intersections of Oppression

- Marxist Perspectives on Revolution: Case Studies from Historical and Modern Contexts

- Marxist Criticism and the Depiction of Social Hierarchies in 19th-century Novels

- The Influence of Marxism on Feminist Theories

- Analyzing Marx’s Theory of Surplus Value and Economic Inequality

- Exploring the National Question in Literary Works: Marxist Analysis of Ethnic and National Identity

- The Relevance of Marx’s Labor Theory of Value in Contemporary Capitalist Economies

- Marx’s Theory of Historical Dialectics: Implications for Understanding Social Progress

Cite this post

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2021, November 12). 165 Karl Marx Essay Topics. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/karl-marx-essay-topics/

"165 Karl Marx Essay Topics." StudyCorgi , 12 Nov. 2021, studycorgi.com/ideas/karl-marx-essay-topics/.

StudyCorgi . (2021) '165 Karl Marx Essay Topics'. 12 November.

1. StudyCorgi . "165 Karl Marx Essay Topics." November 12, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/karl-marx-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "165 Karl Marx Essay Topics." November 12, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/karl-marx-essay-topics/.

StudyCorgi . 2021. "165 Karl Marx Essay Topics." November 12, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/ideas/karl-marx-essay-topics/.

These essay examples and topics on Karl Marx were carefully selected by the StudyCorgi editorial team. They meet our highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, and fact accuracy. Please ensure you properly reference the materials if you’re using them to write your assignment.

This essay topic collection was updated on June 24, 2024 .

Presentations made painless

- Get Premium

121 Marxism Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

Inside This Article

Marxism is a complex and multifaceted ideology that has had a profound impact on politics, economics, and social theory. Whether you are a student studying Marxism in a university course or simply interested in learning more about this influential perspective, there are a plethora of essay topics to explore. In this article, we will provide 121 Marxism essay topic ideas and examples to inspire your research and writing.

- The concept of alienation in Marxist theory

- The role of class struggle in Marxist thought

- The relationship between capitalism and imperialism in Marxist theory

- How does Marxism critique liberal democracy?

- The impact of globalization on Marxist theory

- The role of the state in Marxist thought

- How does Marx define exploitation in a capitalist society?

- The concept of surplus value in Marxist economics

- The relationship between Marxism and feminism

- The role of ideology in maintaining capitalist power structures

- The relevance of Marxist theory in the 21st century

- The connection between Marxism and environmentalism

- How does Marxism critique religion?

- The role of education in perpetuating capitalist ideology

- The relationship between Marxism and postcolonial theory

- The concept of false consciousness in Marxist theory

- The impact of technology on Marxist theory

- The role of culture in perpetuating capitalist hegemony

- The relationship between Marxism and psychoanalysis

- The concept of historical materialism in Marxist thought

- How does Marx define social class?

- The role of the working class in Marxist revolution

- The impact of neoliberalism on Marxist theory

- The relationship between Marxism and anarchism

- The concept of class consciousness in Marxist theory

- How does Marx define the means of production?

- The role of the bourgeoisie in capitalist society

- The impact of imperialism on Marxist theory

- The relationship between Marxism and critical theory

- The concept of dialectical materialism in Marxist philosophy

- How does Marx define the state?

- The role of the proletariat in Marxist revolution

- The impact of colonialism on Marxist theory

- The relationship between Marxism and poststructuralism

- The concept of historical materialism in Marxist history

- How does Marx define social inequality?

- The role of the ruling class in perpetuating capitalist exploitation

- The impact of neoliberal globalization on Marxist theory

- The relationship between Marxism and intersectionality

- The concept of class struggle in Marxist politics

- How does Marx define the ruling class?

- The role of the working class in challenging capitalist hegemony

- The impact of imperialism on Marxist international relations

- The relationship between Marxism and globalization

- The concept of historical materialism in Marxist sociology

- How does Marx define economic exploitation?

- The role of the bourgeoisie in perpetuating capitalist inequality

- The impact of neoliberal capitalism on Marxist theory

- The relationship between Marxism and cultural studies

- The concept of dialectical materialism in Marxist literature

- How does Marx define the capitalist mode of production?

- The role of the proletariat in overthrowing capitalist power structures

- The impact of colonialism on Marxist theory of development

- The relationship between Marxism and decolonial theory

- The concept of historical materialism in Marxist anthropology

- How does Marx define the labor theory of value?

- The role of the ruling class in maintaining capitalist exploitation

- The impact of neoliberal globalization on Marxist political economy

- The relationship between Marxism and queer theory

- The concept of class struggle in Marxist social movements

- How does Marx define the capitalist class system?

- The role of the working class in resisting capitalist oppression

- The impact of imperialism on Marxist theories of imperialism

- The relationship between Marxism and indigenous studies

- The concept of historical materialism in Marxist philosophy of history

- How does Marx define the contradictions of capitalism?

- The role of the bourgeoisie in perpetuating capitalist domination

- The impact of neoliberal capitalism on Marxist theories of crisis

- The relationship between Marxism and disability studies

- The concept of dialectical materialism in Marxist theory of knowledge

- How does Marx define the exploitation of labor?

- The role of the proletariat in challenging capitalist exploitation

- The impact of colonialism on Marxist theories of revolution

- The relationship between Marxism and critical race theory

- The concept of historical materialism in Marxist theories of social change

- How does Marx define the commodification of labor?

- The role of the ruling class in maintaining capitalist power

- The impact of neoliberal globalization on Marxist theories of resistance

- The relationship between Marxism and feminist theory

- The concept of class struggle in Marxist theories of revolution

- How does Marx define the role of ideology in maintaining capitalist hegemony?

- The role of the working class in Marxist theories of social change

- The concept of historical materialism in Marxist theories of history

- How does Marx define the relationship between capitalism and imperialism?

- The role of the bourgeoisie in Marxist theories of exploitation

- The relationship between Marxism and environmental studies

- The concept of dialectical materialism in Marxist theories of knowledge

- How does Marx define the relationship between class and power?

- The role of the proletariat in Marxist theories of revolution

- The impact of colonialism on Marxist theories of resistance

- How does Marx define the relationship between labor and value?

- The role of the ruling class in Marxist theories of domination

- How does Marx define the role of the state in maintaining capitalist power?

- How does Marx define the relationship between capitalism and globalization?

- How does Marx define the relationship between class and ideology?

- How does Marx define the relationship between labor and power?

- How does Marx define the role of the state in perpetuating capitalist hegemony?

These essay topic ideas and examples are just a starting point for exploring the rich and diverse world of Marxism. Whether you are interested in economic theory, political philosophy, or social movements, there is a wealth of material to delve into within the Marxist tradition. By engaging with these topics and conducting your own research, you can deepen your understanding of Marxism and its continued relevance in today's world.

Want to research companies faster?

Instantly access industry insights

Let PitchGrade do this for me

Leverage powerful AI research capabilities

We will create your text and designs for you. Sit back and relax while we do the work.

Explore More Content

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

© 2024 Pitchgrade

Karl Marx: ten things to read if you want to understand him

Lecturer in Political Science, University of Exeter

Lecturer in Politics, Manchester Metropolitan University

Disclosure statement

James Muldoon is a member of the British Labour Party.

Robert P. Jackson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Manchester Metropolitan University and University of Exeter provide funding as members of The Conversation UK.

View all partners

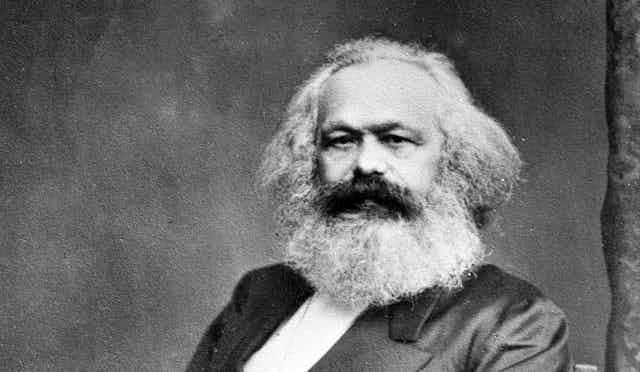

As the world reflects on 200 years since the birth of Karl Marx, his writings are being sampled by more and more people. If you’re new to the work of one of the greatest social scientists of all time, here’s where to start.

Marx’s own writing

James Muldoon, University of Exeter

The long history of brutal, totalitarian “Marxist” regimes around the world has left many people with the impression that Marx was an authoritarian thinker. But readers who dive into his work for the first time are often surprised to discover an Enlightenment humanist and a philosopher of emancipation, one who envisaged well-rounded human beings living rich, varied and fulfilling lives in a post-capitalist society. Marx’s writings don’t just propose a revolutionary political project; they offer a moral critique of the alienation of individuals living in capitalist societies.

1. An Introduction to a Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right ( Available here )

Originally published in 1844 in a radical Parisian newspaper, this fascinating short essay captures many of Marx’s early criticisms of modern society and his radical vision of emancipation. It also introduces several of the key themes that would shape his later writings.

Marx claims that the bourgeois revolutions of the 18th century may have benefited a wealthy and educated class, but did not challenge private forms of domination in the factory, home and field. Marx theorises the revolutionary subject of the working class, and proposes its historic task: to abolish private property and achieve self-emancipation.

2. Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 ( Available here )

Not published within his lifetime, and only released in 1932 by officials in the Soviet Union, these notes written by Marx are an important source for his theory of capitalist alienation. They reveal the essential outline of what “Marxism” is, and provide the philosophical basis for humanist readings of Marx.

In these manuscripts, Marx analyses the harmful effects of the organisation of labour in modern industrial societies. Modern workers, he argues, have become estranged from the goods they produced, from their own labour activity, and from their fellow workers. Rather than achieving a sense of satisfaction and self-actualisation in their labour, workers are left exhausted and spiritually depleted. For Marx, the antidote to modern alienation is a humanist conception of communism based on free and cooperative production.

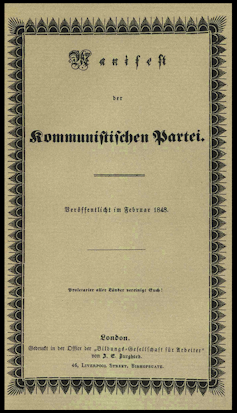

3. The Communist Manifesto ( Available here )

Opening with the famous line, “a spectre is haunting Europe – the spectre of communism”, the Communist Manifesto has become one of the most influential political documents ever written. Co-authored with Friedrich Engels, this pamphlet was commissioned by London’s Communist League and published on the cusp of the various revolutions that rocked Europe in 1848.

The manifesto presents Marx’s materialist conception of history and his theory of class struggle. It outlines the growing tensions between the bourgeoisie and the proletariat under capitalist relations of production, and predicts the triumph of the workers.

4. The German Ideology ( Available here )

For anyone seeking to understand Marxism’s deeper philosophical and historical underpinnings, this is one of his most important texts. Written in around 1846, again with Engels, The German Ideology provides the full development of the two men’s methodology, historical materialism , which seeks to understand the history of humankind based on the development of its modes of production.

Marx and Engels argue that individuals’ social consciousness depends on the material conditions in which they live. He traces the development of different historical modes of production and argues that the present capitalist one will be replaced by communism. Some interpreters view this text as the point where Marx’s thought began to emerge in its mature form.

5. Capital (Volume 1) ( Available here )

Published in 1867, Capital is Marx’s critical diagnosis of the capitalist mode of production. In it, he details the ultimate source of wealth under capitalism: the exploited labour of workers. Workers are free to sell their labour to any capitalist, but since they must sell their labour in order to survive, they are dominated by the class of capitalists as a whole. And through their labour, workers reproduce and reinforce both the economic conditions of their existence and also the social and ideological structure of their society.

In Capital, Marx outlines a number of capitalism’s internal contradictions, such as a declining rate of profit and the tendency for the formation of capitalist monopolies. While certain aspects of the text have been questioned , Marx’s analysis informs economic debate to this day. For anyone trying to understand why capitalism keeps falling into crisis, it’s still hugely relevant.

On Marx and Marxism

Robert Jackson, Manchester Metropolitan University

1. A Companion to Marx’s Capital – David Harvey

From social movements to student reading groups, from Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century to articles in the Financial Times , Marx’s economic writings are at the centre of debate once again. And one of the figures most associated with these discussions is the geographer David Harvey.

Based on his popular online lecture series, Reading Capital with David Harvey , this book makes Marx’s Capital accessible to a broader audience. Guiding readers through Marx’s challenging (but rewarding) study of the “laws of motion” of capitalism, Harvey provides an open and critical reading. He draws out the connections between this world-changing text and today’s society – a society which, after all, is still shaped by the economic crisis of 2008.

2. Karl Marx: A Nineteenth-Century Life – Jonathan Sperber

For Jonathan Sperber , a historian of modern Germany, Marx is “more a figure from the past than a prophet of the present”. And, as its title suggests, this biography places Marx’s life in the context of the 19th century. It’s an accessible introduction to the history of his political thought, particularly as a critic of his contemporaries. Sperber discusses Marx in his many roles – a son, a student, a journalist and political activist – and introduces the multitude of characters connected with him. While Francis Wheen’s well-known Karl Marx: A Life is a more freewheeling account, Sperber’s writing is both highly readable and more deeply rooted in historical scholarship.

3. From #BlackLivesMatter to Black Liberation – Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor

Writing about the US just over 150 years ago, Marx noted that: “Labour in a white skin cannot emancipate itself where it is branded in a black skin.” And the influence of his ideas about the relationship between race and class is visible in debates right up to the present day.

Penned by academic and activist Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor , who came to popular prominence in the recent #BlackLivesMatter movement, this is a timely read for those interested in the various ways Marx’s thought is being rebooted for the 21st century. A penetrating book, it connects the origins of racism to the structures of economic inequality. With plenty of Marxist ideas (among others) in her toolbox, Taylor critically examines the notion of a “colour-blind” society and the US’s post-Obama order to great effect.

4. Why Marx was Right – Terry Eagleton

A call to reconsider the widely accepted notion that Marx is a “dead dog” from renowned literary theorist Terry Eagleton . In this provocative and highly readable book, Eagleton questions the plausibility of ten of the most common objections to Marx’s thought – among them, that Marx’s ideas are outdated in post-industrial societies, that Marxism always leads to tyranny in practice, that Marx’s theory is deterministic and undermines human freedom. Always witty and passionate, Eagleton peppers his spirited defence (with some reservations) of Marx’s ideas with his own literary and cultural insights.

5. Jacobin magazine – edited by Bhaskar Sunkara (available online )

In the era of the Occupy movement , “ taking a knee ” and #MeToo , the discussion of Marx’s ideas has gained an increasing presence on the internet. One of the most notable examples is the socialist magazine and online platform Jacobin, edited by Bhaskar Sunkara , which currently reaches around 1m viewers a month .

Covering topics from international politics and environmental movements to the recent education strikes in Oklahoma and West Virginia and Bernie Sanders’s presidential campaign, it’s a lively source for anyone who wants to see an analysis of contemporary politics that’s influenced by Marx’s thought.

- Social sciences

- Das Kapital

- Friedrich Engels

Finance Manager

Head of School: Engineering, Computer and Mathematical Sciences

Educational Designer

Organizational Behaviour – Assistant / Associate Professor (Tenure-Track)

Apply for State Library of Queensland's next round of research opportunities

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Top Questions

Historical materialism

- Analysis of society

- Analysis of the economy

- Class struggle

- The contributions of Engels

- The work of Kautsky and Bernstein

- The radicals

- The Austrians

- The dictatorship of the proletariat

- Marxism in Cuba

- Marxism in the developing world

- Marxism in the West

Where did Marxism come from?

Why is marxism important, how is marxism different from other forms of socialism, how does marxism differ from leninism.

- How did Karl Marx die?

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Social Sci LibreTexts - Marxism

- Alpha History - Marxism

- The Library of Economics and Liberty - Marxism

- Simply Psychology - Marxism: Definition, Theory, Ideology, Examples, and Facts

- Table Of Contents

Marxism originated in the thought of the radical philosopher and economist Karl Marx , with important contributions from his friend and collaborator Friedrich Engels . Marx and Engels authored The Communist Manifesto (1848), a pamphlet outlining their theory of historical materialism and predicting the ultimate overthrow of capitalism by the industrial proletariat . Engels edited the second and third volumes of Marx’s analysis and critique of capitalism, Das Kapital , both published after Marx’s death.

In the mid-19th century, Marxism helped to consolidate, inspire, and radicalize elements of the labour and socialist movements in western Europe, and it was later the basis of Marxism-Leninism and Maoism , the revolutionary doctrines developed by Vladimir Lenin in Russia and Mao Zedong in China, respectively. It also inspired a more moderate form of socialism in Germany, the precursor of modern social democracy .

Under socialism , the means of production are owned or controlled by the state for the benefit of all, an arrangement that is compatible with democracy and a peaceful transition from capitalism . Marxism justifies and predicts the emergence of a stateless and classless society without private property. That vaguely socialist society, however, would be preceded by the violent seizure of the state and the means of production by the proletariat , who would rule in an interim dictatorship .

Marxism predicted a spontaneous revolution by the proletariat , but Leninism insisted on the need for leadership by a vanguard party of professional revolutionaries (such as Vladimir Lenin himself). Marxism predicted a temporary dictatorship of the proletariat , whereas Leninism, in practice, established a permanent dictatorship of the Communist Party . Marxism envisioned a revolution of proletarians in industrialized countries, while Leninism also emphasized the revolutionary potential of peasants in primarily agrarian societies (such as Russia).

Marxism , a body of doctrine developed by Karl Marx and, to a lesser extent, by Friedrich Engels in the mid-19th century. It originally consisted of three related ideas: a philosophical anthropology , a theory of history, and an economic and political program. There is also Marxism as it has been understood and practiced by the various socialist movements, particularly before 1914. Then there is Soviet Marxism as worked out by Vladimir Ilich Lenin and modified by Joseph Stalin , which under the name of Marxism-Leninism ( see Leninism ) became the doctrine of the communist parties set up after the Russian Revolution (1917). Offshoots of this included Marxism as interpreted by the anti-Stalinist Leon Trotsky and his followers, Mao Zedong ’s Chinese variant of Marxism-Leninism, and various Marxisms in the developing world. There were also the post-World War II nondogmatic Marxisms that have modified Marx’s thought with borrowings from modern philosophies, principally from those of Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger but also from Sigmund Freud and others.

(Read Leon Trotsky’s 1926 Britannica essay on Lenin.)

The thought of Karl Marx

The written work of Marx cannot be reduced to a philosophy , much less to a philosophical system. The whole of his work is a radical critique of philosophy, especially of G.W.F. Hegel ’s idealist system and of the philosophies of the left and right post- Hegelians . It is not, however, a mere denial of those philosophies. Marx declared that philosophy must become reality. One could no longer be content with interpreting the world; one must be concerned with transforming it, which meant transforming both the world itself and human consciousness of it. This, in turn, required a critique of experience together with a critique of ideas. In fact, Marx believed that all knowledge involves a critique of ideas. He was not an empiricist . Rather, his work teems with concepts (appropriation, alienation , praxis, creative labour, value, and so on) that he had inherited from earlier philosophers and economists, including Hegel, Johann Fichte , Immanuel Kant , Adam Smith , David Ricardo , and John Stuart Mill . What uniquely characterizes the thought of Marx is that, instead of making abstract affirmations about a whole group of problems such as human nature , knowledge, and matter , he examines each problem in its dynamic relation to the others and, above all, tries to relate them to historical, social, political, and economic realities.

In 1859, in the preface to his Zur Kritik der politischen Ökonomie ( Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy ), Marx wrote that the hypothesis that had served him as the basis for his analysis of society could be briefly formulated as follows:

In the social production that men carry on, they enter into definite relations that are indispensable and independent of their will, relations of production which correspond to a definite stage of development of their material forces of production. The sum total of these relations of production constitutes the economic structure of society, the real foundation, on which rises a legal and political superstructure, and to which correspond definite forms of social consciousness . The mode of production in material life determines the general character of the social, political, and intellectual processes of life. It is not the consciousness of men which determines their existence; it is on the contrary their social existence which determines their consciousness.

Raised to the level of historical law, this hypothesis was subsequently called historical materialism. Marx applied it to capitalist society, both in Manifest der kommunistischen Partei (1848; The Communist Manifesto ) and Das Kapital (vol. 1, 1867; “Capital”) and in other writings. Although Marx reflected upon his working hypothesis for many years, he did not formulate it in a very exact manner: different expressions served him for identical realities. If one takes the text literally, social reality is structured in the following way:

1. Underlying everything as the real basis of society is the economic structure. This structure includes (a) the “material forces of production,” that is, the labour and means of production, and (b) the overall “relations of production,” or the social and political arrangements that regulate production and distribution. Although Marx stated that there is a correspondence between the “material forces” of production and the indispensable “relations” of production, he never made himself clear on the nature of the correspondence, a fact that was to be the source of differing interpretations among his later followers.

2. Above the economic structure rises the superstructure, consisting of legal and political “forms of social consciousness” that correspond to the economic structure. Marx says nothing about the nature of this correspondence between ideological forms and economic structure, except that through the ideological forms individuals become conscious of the conflict within the economic structure between the material forces of production and the existing relations of production expressed in the legal property relations. In other words, “The sum total of the forces of production accessible to men determines the condition of society” and is at the base of society. “The social structure and the state issue continually from the life processes of definite individuals . . . as they are in reality , that is acting and materially producing.” The political relations that individuals establish among themselves are dependent on material production, as are the legal relations. This foundation of the social on the economic is not an incidental point: it colours Marx’s whole analysis. It is found in Das Kapital as well as in Die deutsche Ideologie (written 1845–46; The German Ideology ) and the Ökonomisch-philosophische Manuskripte aus dem Jahre 1844 ( Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 ).

Evaluate the Marxist View of the Role of Education in Society

Last Updated on November 18, 2022 by Karl Thompson

According to Marxists, modern societies are capitalist, and are structured along class-lines, and such societies are divided into two major classes – The Bourgeois elite who own and control the means of production who exploit the Proletariat by extracting surplus value from them.

Traditional Marxists understand the role of education in this context – education is controlled by the elite class (The Bourgeoisie) and schools forms a central part of the superstructure through which they maintain ideological control of the proletariat.

Education has four main roles in society according to Marxists:

Louis Althusser argued that state education formed part of the ‘ ideological state apparatus ‘: the government and teachers control the masses by injecting millions of children with a set of ideas which keep people unaware of their exploitation and make them easy to control.

According to Althusser, education operates as an ideological state apparatus in two ways; Firstly, it transmits a general ideology which states that capitalism is just and reasonable – the natural and fairest way of organising society, and portraying alternative systems as unnatural and irrational Secondly, schools encourage pupils to passively accept their future roles, as outlined in the next point…

The second function schools perform for Capitalism is that they produce a compliant and obedient workforce…

In ‘Schooling in Capitalist America’ (1976) Bowles and Gintis suggest that there is a correspondence between values learnt at school and the way in which the workplace operates. The values, they suggested, are taught through the ‘Hidden Curriculum’, which consists of those things that pupils learn through the experience of attending school rather than the main curriculum subjects taught at the school. So pupils learn those values that are necessary for them to tow the line in menial manual jobs.

Fourthly, schools legitimate class inequality . Marxists argue that in reality class background and money determines how good an education you get, but people do not realize this because schools spread the ‘myth of meritocracy’ – in school we learn that we all have an equal chance to succeed and that our grades depend on our effort and ability. Thus if we fail, we believe it is our own fault. This legitimates or justifies the system because we think it is fair when in reality it is not.

Willis argued that pupils rebelling are evidence that not all pupils are brainwashed into being passive, subordinate people as a result of the hidden curriculum. Willis therefore criticizes Traditional Marxism. These pupils also realise that they have no real opportunity to succeed in this system, so they are clearly not under ideological control.

Evaluating the Marxist Perspective on Education

Traditional Marxist views of education are extremely dated, even the the new ‘Neo-Marxist’ theory of Willis is 40 years old, but how relevant are they today?

To criticise the idea of the Ideological State Apparatus, Henry Giroux, says the theory is too deterministic. He argues that working class pupils are not entirely molded by the capitalist system, and do not accept everything that they are taught. Also, education can actually harm the Bourgeois – many left wing, Marxist activists are university educated, so clearly they do not control the whole of the education system.

However, if you look at the world’s largest education system, China, this could be seen as supporting evidence for the idea of the correspondence principle at work – many of those children will go into manufacturing, as China is the world’s main manufacturing country in the era of globalisation.

The Marxist Theory of the reproduction of class inequality and its legitimation through the myth of meritocracy does actually seem to be true today. There is a persistent correlation between social class background and educational achievement – with the middle classes able to take advantage of their material and cultural capital to give their children a head start and then better grades and jobs. It is also the case that children are not taught about this unfairness in schools, although a small handful do learn about it in Sociology classes.

Signposting and Related Posts

This essay was written as a top band answer for a 30 mark question which might appear in the education section of the AQA’s A-level sociology 7192/1 exam paper: Education with Theory and Methods.

The full knowledge post relevant to the above essay is here:

Share this:

4 thoughts on “evaluate the marxist view of the role of education in society”, leave a reply cancel reply.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from ReviseSociology

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

32 Student Example: Marxist Criticism

The following student essay example of Marxist Criticism is taken from Beginnings and Endings: A Critical Edition . This is the publication created by students in English 211. This essay discusses Raymond Carver’s short story, “A Small, Good Thing.”

“A Small, Good Thing” by Raymond Carver and the 1980s AIDS Epidemic

By Jasper Chappel

Raymond Carver’s short story “A Small, Good Thing” was published in 1983, in his collection Cathedral. In 1983 in the United States, the AIDS epidemic was barely beginning to be understood by the CDC and the general public. Under President Ronald Reagan since 1981, anti-communist and pro-capitalist sentiment was expected of Americans because of tense relations with the USSR. This political climate informed Carver’s writing of “A Small, Good Thing,” and the previous version of the same story published in 1981, titled “The Bath;” Carver’s personal life partially influenced the drastic changes between each story, and so did the emerging political tensions caused by the AIDS epidemic and relations with the USSR. “A Small, Good Thing,” despite being written in a turbulent time, encourages people to value each other, put less trust in institutions such as government and healthcare, and ultimately come together in times of hardship.

The baker is a criticism of capitalism and excessive labor with unfair pay. He has lost part of his humanity to his work, because maintaining financial security is a more immediate concern than forming relationships; he and other unnamed employees represent the proletariat. His behavior throughout the story shows his lack of feeling towards other people, and at the end, he admits as much, saying, “I’m just a baker. I don’t claim to be anything else… [M]aybe years ago I was a different kind of human being” (page 26). Industry has forced the characters to lose their individuality – none of the nurses are named or physically distinguishable from each other, and they do not offer Ann and Howard comfort or answers. When asked questions about Scotty’s condition, they simply say, “Doctor Francis will be here in a few minutes,” (page 6). Doctor Francis has reached a high enough class that he can retain some humanity while still doing his job, which is why he is afforded a name. However, he is nearing the status of the bourgeoisie, which is ultimately why he fails to give Scotty the correct diagnosis and treatment. He and Howard are somewhat similar in this regard; because Howard has the privilege to leave his job in the middle of a work day, and for an indefinite amount of time when Scotty is hospitalized, the audience can assume Howard is nearing a high-class position. He is not expendable, like a nurse or a baker would be.

Ann appears to be a full-time mom, and while this is unpaid labor, the reader is led to understand her emotions the most because she retains the most humanity in her job; she simply has the privilege to not work for a company. Her trade is motherhood, and when this is stripped from her, she feels more aimless than the others; just like if the nurse or the baker lost their positions, Ann forms her identity around the job of being a mom. The difference is that it is her job to empathize with others, to care for others, and she can find another niche to fill without sending in an application first. Her grief manifests in being unable to care for her son, despite her skills; she knows Scotty is in a coma and that something has gone horribly wrong, but because the bourgeoisie does not value self-employed, unpaid labor, her concerns are brushed aside.

From one perspective, Ann benefits from being a mother. From another, her characterization has reduced her to being only a mother. The only outside information we have for another main character is what Howard and the baker tell us about their lives. While Howard is driving home from the hospital, he reflects on his life and his good fortune, or his privilege. Ann does not do the same – the audience is unsure of whether Ann thinks the marriage is successful, if she went to college, or if she gave anything up to become a mother. She is only a mother and wife – a loving one, but a one-dimensional character. It seems that Ann is defined only by the fact she has a son. Ann’s designated role to help the men in the story remember their humanity is a stereotypically feminine role that is largely informed by Raymond Carver’s identity and life experiences, but is also in line with the idea that motherhood is a full-time job unrecognized by capitalism.

The bourgeoisie in this story are best represented by the hospital and doctor, and the situation with Scotty exposes the flawed system the proletariat have to live under. Scotty represents its most vulnerable victims, and the family Ann meets in the lobby of the hospital represents how tragedy can touch all our lives regardless of class or race. Ann and Howard learn through the events of the story, despite being middle-class and white, that certain tragedies touch all lives; this is a translation of the AIDS epidemic into literature. Disease does not discriminate based off class, sexuality, or race, but institutions and governments do.

Scotty has no speaking lines–the narrator only supplies information on what he saying, so the audience doesn’t have access to his exact words. All we know about him is that he probably likes aliens, has one friend he used to walk to school with, and “howls” before he dies, a very inhuman noise. Even though the story revolves around his injury, he only serves as a character who affects other characters. His injury allows the audience to see the contrast between employees who take care of people as a job, and people who take care of others free from industry interference. He also serves to bring the baker and Ann together; the baker needed to be reminded of his humanity and have a reason to turn his back on the capitalist system for a while. Ann is the most likely character to help him reconnect with his humanity, and in her grief she is more human than any other character. Although Howard also shows his humanity in his grief, it is Ann who helps him along, “’There, there,’ she said tenderly. ‘Howard, he’s gone. He’s gone now and we’ll have to get used to that. To being alone” (page 22). When Scotty’s death makes his parents feel alienated, just as capitalism alienates people from each other to prevent an uprising, they start to accept this; then the baker calls again, and Ann’s anger at his behavior pushes them into action, and eventually reconciliation and comfort.

When Ann encounters the black family in the waiting room, they serve as a mirror for her situation, and represent understanding each other’s humanity despite differences. There is a previous version of this short story called “The Bath,” which does not specify the race of the family, does not include the two dark-skinned orderlies, and lacks the reconciliation with the baker. Part of the fear around AIDS was due to the uncertainty about how it spread, but there was also an element of stigma around African-American populations and their inaccurate image in the media as drug users (therefore, re-use needles and spread AIDS). Early on, it became clear that AIDS was spreading through bodily fluids, but more information than that tended to be conflicting.

In 1985, according to the article “Save Our Kids, Keep AIDS Out” by Jennifer Brier, black and white families would unite in Queens to protest the CDC regulations stating that children diagnosed with AIDS should be allowed in public schools. We can see this sentiment represented before this occurrence in Ann’s desire to connect with the black family in the waiting room. Just like the mothers in the article fear their children being exposed to AIDS at school, a hospital must have been a nightmare for a mother in this time period. Seeing Scotty have his blood drawn, and other needles inserted into his veins, probably caused her panic each time; not only because his condition was not improving, but also for the risk of contracting AIDS the longer he stayed in the hospital. Scotty’s hospital stay can be considered a metaphor for how AIDS was considered during the time of publication. It comes out of nowhere, just like the car that hit Scotty, then disappeared without a trace. Those who are hit seem fine at first, but progressively, their condition declines. The doctors and nurses do not know enough about the disease, and sometimes, their intuition is wrong, causing tragic deaths. The message the audience is left with is this: a mother knows best for her child. This is echoed in the later movement in Queens, “Thus, parents and local communities, not a dishonest city bureaucracy or out-of-touch scientific establishment, were better able to make decisions about local children” (Brier 4).

In “A Small, Good Thing,” instead of exploiting the fear people had around the AIDS epidemic, Carver encourages people to find common ground and come together. Doctor Francis expresses his regrets in not being able to save Scotty, the family in the waiting room symbolizes connecting with each other despite differences, and the baker is able to acknowledge his loss of humanity over the years after witnessing Ann and Howard’s grief. This short story is a touching addition to the literary time period, and handles each political undertone with care and empathy.

Works Cited

Brier, Jennifer. “‘Save Our Kids, Keep AIDS out:” Anti-AIDS Activism and the Legacy of Community Control in Queens, New York.” Journal of Social History, vol. 39, no. 4, 2006, pp. 965–987. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3790237 . Accessed 14 May 2021.

Carver, Raymond. “A Small, Good Thing.” Ploughshares, vol. 8, no. 2/3, 1982, pp. 213–240. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40348924 . Accessed 14 May 2021.

Carver, Raymond. “The Bath.” Columbia: A Journal of Literature and Art, no. 6, 1981, pp. 32–41. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/42744338 . Accessed 14 May 2021.

McCaffery, Larry, et al. “An Interview with Raymond Carver.” Mississippi Review, vol. 14, no. 1/2, 1985, pp. 62–82. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/20115387 . Accessed 14 May 2021.

Critical Worlds Copyright © 2024 by Liza Long is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Encyclopedia

Writing with artificial intelligence, marxist criticism.

- © 2023 by Angela Eward-Mangione - Hillsborough Community College

Marxist Criticism refers to a method you'll encounter in literary and cultural analysis. It breaks down texts and societal structures using foundational concepts like class, alienation, base, and superstructure. By understanding this, you'll gain insights into how power dynamics and socio-economic factors influence narratives and cultural perspectives

What is Marxist Criticism?

Marxist Criticism refers to both

- an interpretive framework

- a genre of discourse .

Marxist Criticism as both a theoretical approach and a conversational genre within academic discourse . Critics using this framework analyze literature and other cultural forms through the lens of Marxist theory, which includes an exploration of how economic and social structures influence ideology and culture. For example, a Marxist reading of a novel might explore how the narrative reinforces or challenges the existing social hierarchy and economic inequalities.

Marxist Criticism prioritizes four foundational Marxist concepts:

- class struggle

- the alienation of the individual under capitalism

- the relationship between a society’s economic base and

- its cultural superstructure.

Related Concepts

Dialectic ; Hermeneutics ; Literary Criticism ; Semiotics ; Textual Research Methods

Why Does Marxist Criticism Matter?

Marxist criticism thus emphasizes class, socioeconomic status, power relations among various segments of society, and the representation of those segments. Marxist literary criticism is valuable because it enables readers to see the role that class plays in the plot of a text.

What Are the Four Primary Perspectives of Marxism?

| Class | a classification or grouping typically based on income and education |

| Alienation | a condition Karl Heinrich Marx ascribed to individuals in a capitalist economy who lack a sense of identification with their labor and products. The estrangement individuals feel in capitalist societies, where they become disconnected from their work, the products they produce, and even themselves. |

| Base | the means (e.g., tools, machines, factories, natural resources) and relations (e.g., Proletariat, Bourgeoisie) or production that shape and are shaped by the superstructure (the dominant aspect in society). Marxist criticism theorizes that the economic means of production within society account for the base. |

| Superstructure | the social institutions such as systems of law, morality, education, and their related ideologies, that shape and are shaped by the base. Human institutions and ideologies—including those relevant to a patriarchy—that produce art and literary texts comprise the superstructure. |

Did Karl Marx Create Marxist Criticism?

Karl Marx himself did not create Marxist criticism as a literary or cultural methodology . He was a philosopher, economist, and sociologist, and his works laid the foundation for Marxist theory in the context of social and economic analysis. The key concepts that Marx developed—such as class struggle, the theory of surplus value, and historical materialism—are central to understanding the mechanisms of capitalism and class relations.

Marxist criticism as a distinct approach to literature and culture developed later, as thinkers in the 20th century began to apply Marx’s ideas to the arts and humanities. It is a product of various scholars and theorists who found Marx’s social theories to be useful tools for analyzing and critiquing literature and culture. These include figures such as György Lukács, Walter Benjamin, Antonio Gramsci, and later the Frankfurt School, among others, who expanded Marxist theory into the realms of ideology, consciousness, and cultural production.

So, while Marx provided the ideological framework, it was later theorists who adapted his ideas into what is now known as Marxist criticism.

Who Are the Key Figures in Marxist Theory?

Bressler notes that “Marxist theory has its roots in the nineteenth-century writings of Karl Heinrich Marx, though his ideas did not fully develop until the twentieth century” (183).

Key figures in Marxist theory include Bertolt Brecht, Georg Lukács, and Louis Althusser. Although these figures have shaped the concepts and path of Marxist theory, Marxist literary criticism did not specifically develop from Marxism itself. One who approaches a literary text from a Marxist perspective may not necessarily support Marxist ideology.

For example, a Marxist approach to Langston Hughes’s poem “ Advertisement for the Waldorf-Astoria ” might examine how the socioeconomic status of the speaker and other citizens of New York City affect the speaker’s perspective. The Waldorf Astoria opened during the midst of the Great Depression. Thus, the poem’s speaker uses sarcasm to declare, “Fine living . . . a la carte? / Come to the Waldorf-Astoria! / LISTEN HUNGRY ONES! / Look! See what Vanity Fair says about the / new Waldorf-Astoria” (lines 1-5). The speaker further expresses how class contributes to the conflict described in the poem by contrasting the targeted audience of the hotel with the citizens of its surrounding area: “So when you’ve no place else to go, homeless and hungry / ones, choose the Waldorf as a background for your rags” (lines 15-16). Hughes’s poem invites readers to consider how class restricts particular segments of society.

What are the Foundational Questions of Marxist Criticism?

- What classes, or socioeconomic statuses, are represented in the text?

- Are all the segments of society accounted for, or does the text exclude a particular class?

- Does class restrict or empower the characters in the text?

- How does the text depict a struggle between classes, or how does class contribute to the conflict of the text?

- How does the text depict the relationship between the individual and the state? Does the state view individuals as a means of production, or as ends in themselves?

Example of Marxist Criticism

- The Working Class Beats: a Marxist analysis of Beat Writing and (studylib.net)

Discussion Questions and Activities: Marxist Criticism

- Define class, alienation, base, and superstructure in your own words.

- Explain why a base determines its superstructure.

- Choose the lines or stanzas that you think most markedly represent a struggle between classes in Langston Hughes’s “ Advertisement for the Waldorf-Astoria .” Hughes’s poem also addresses racial issues; consider referring to the relationship between race and class in your written response.

- Contrast the lines that appear in quotation marks and parentheses in Hughes’s poem. How do these lines differ? Does it seem like the lines in parentheses respond to the lines in quotation marks, the latter of which represent excerpts from an advertisement for the Waldorf-Astoria published in Vanity Fair? How does this contrast illustrate a struggle between classes?

- What is Hughes’s purpose for writing “ Advertisement for the Waldorf-Astoria ?” Defend your interpretation with evidence from the poem.

Brevity - Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence - How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow - How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity - Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style - The DNA of Powerful Writing

Recommended

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Structured Revision – How to Revise Your Work

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Credibility & Authority – How to Be Credible & Authoritative in Research, Speech & Writing

Citation Guide – Learn How to Cite Sources in Academic and Professional Writing

Page Design – How to Design Messages for Maximum Impact

Suggested edits.

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Other Topics:

Citation - Definition - Introduction to Citation in Academic & Professional Writing

- Joseph M. Moxley

Explore the different ways to cite sources in academic and professional writing, including in-text (Parenthetical), numerical, and note citations.

Collaboration - What is the Role of Collaboration in Academic & Professional Writing?

Collaboration refers to the act of working with others or AI to solve problems, coauthor texts, and develop products and services. Collaboration is a highly prized workplace competency in academic...

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions...

Grammar refers to the rules that inform how people and discourse communities use language (e.g., written or spoken English, body language, or visual language) to communicate. Learn about the rhetorical...

Information Literacy - Discerning Quality Information from Noise

Information Literacy refers to the competencies associated with locating, evaluating, using, and archiving information. In order to thrive, much less survive in a global information economy — an economy where information functions as a...

Mindset refers to a person or community’s way of feeling, thinking, and acting about a topic. The mindsets you hold, consciously or subconsciously, shape how you feel, think, and act–and...

Rhetoric: Exploring Its Definition and Impact on Modern Communication

Learn about rhetoric and rhetorical practices (e.g., rhetorical analysis, rhetorical reasoning, rhetorical situation, and rhetorical stance) so that you can strategically manage how you compose and subsequently produce a text...

Style, most simply, refers to how you say something as opposed to what you say. The style of your writing matters because audiences are unlikely to read your work or...

The Writing Process - Research on Composing

The writing process refers to everything you do in order to complete a writing project. Over the last six decades, researchers have studied and theorized about how writers go about...

Writing Studies

Writing studies refers to an interdisciplinary community of scholars and researchers who study writing. Writing studies also refers to an academic, interdisciplinary discipline – a subject of study. Students in...

Featured Articles

Marxist Analysis Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Exploitation of resources, domination of the markets.

Marxism is a social, political, and economic ideology pioneered by German philosophers, Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, in the early part of the 19 th century. This ideology interprets human development through the history from materialistic point of view. Marxists hold that materialism is the foundation of society since; human beings must satisfy their basic needs before embarking on secondary needs such as politics, arts, science, and religion, among others.

Since capitalism is a dominant economic system, Marxist analysis suggests that capitalism oppresses the poor and empowers the rich; thus, it creates two antagonistic classes in society, which ultimately lead to revolution struggle of classes. Rosenberg (2007) argues that Marxists perceive capitalism as a form of an economic system that creates inequality in the society by favouring accumulation of wealth and class struggles (p. 8).

Therefore, Marxist analysis of a capitalism system on the international scale shows that it entails accumulation of capital from the poor countries into the rich countries thus causes global inequality and class struggles among nations. The existence of massive global inequality validates Marxist analysis that capitalism enhances global inequality.

Marxists view international relations as a complex system of capitalism that has penetrated and integrated into every aspect of production in the world. Since the basic ideology of capitalism is to accumulate wealth, developed countries employed capitalism system to infiltrate into developing countries, acquire resources, and control various modes of production.

During the colonial times, developed countries scrambled for resources in developing countries and accumulated a considerable deal of wealth, for they did not only obtain raw materials for their industries, but also cheap labour.

Milios (2000) asserts that there was massive exploitation of resources from developing countries during the colonial period, which led to unequal development of nations across the world (p.285). Thus, the economic, social, and political development gaps between developed and developing countries are attributes of capitalism system according to Marxist analysis.

It is true that, after colonialism, developing countries attained their independence; regrettably, neo-colonialism persisted as developing countries still employed capitalism strategies by establishing multinational companies. The objective of establishing multinational companies was to control modes of production and create monopoly in the industrial sector.

Since industries contribute significantly to economic growth and development of a country, monopolization of industries, by multinational companies, provides an opportunity for developed countries to amass wealth, a practice that leads to inequality.

According to Walker and Greenberg (2003), monopolization of industries by multinational companies infiltrated the ideology of industrial capitalism that led into increased cost of manufactured goods (p.38). The cost of manufactured goods increased since multinational companies wanted to exploit industrial resources and reap huge profits. Ultimately, industrial capitalism resulted into global inequality as resources flowed from developing countries to industrialized nations.

Marxists also argue that global inequality occurs due to unequal distribution of power and resources among various classes of people created by capitalistic systems. Capitalism creates different classes of people because accessibility to income-generating resources or employment, determines one’s capacity to emancipate from economic oppression in a capitalistic system.

Marxists argue that working classes are people who ensure that routine activities run in industries, for they perform activities such as producing commodities, selling, and managing organizational tasks under capitalist management that exploits them maximally.

Wolff and Zacharias (2007) argue that, from 1989 to 2000, interclass inequality in the United States increased from 30% to 42% (p.24). This trend is also similar in Europe since capitalist classes accumulate most resources with time. Overall, interclass inequality is increasing across the world since the current economic systems are virtually capitalistic.

Marxists perceive globalization as a construct of capitalism that results into power and class struggles. Individual members of the society are competing for the available resources so that they can attain social classes of their choice.

Moreover, countries and mega-companies are also striving to achieve international domination by keeping abreast with the demands of globalization. Given that the global economy is subject to local factors such as surplus and deficits, consumers and producers, which regulate it delicately in the world of capitalism, inequality is a weak link that determines their movement.

Thus, from a Marxist point of view, capitalism is shaping individual, companies, society and countries through globalization towards power and class struggles. Kuhn (2011) argues that globalization provides capitalists with international infrastructure that they employ to penetrate countries and amass wealth through free markets (p.17). Therefore, creation of free-market provides a favorable business environment that allows free movement of goods, services, and capital; therefore, it enhances global inequality.

Since developed countries have a competitive advantage in the world’s market, they advocate for liberalized trade and free markets. According to a Marxist analysis, the wave of globalization that is sweeping across the world is preparing countries to enter into liberalized trade and free markets, which are very competitive for developing countries to survive.

In the liberalized trade, no one regulates the movement of goods and services since they self-regulate through forces of supply and demand. The forces of supply and demand increase inequality as essential goods and services will move to developed countries leaving developed countries with deficiency.